Abstract

The current research was designed to examine the effects of emotional intelligence on both economic and social outcomes, as well as to explore the extent to which rapport, bargaining strategy, and judgment accuracy would mediate relationships between emotional intelligence and negotiation outcomes. Upper-level business students (284 individuals, 142 dyads) were pre-tested on emotional intelligence using the 33-item measure from Schutte et al. (Personal Individ Differ 25:167–177, 1998). They were then recruited to participate in a job contract negotiation in which one party played the role of personnel manager and the other played the role of a new employee. Emotional intelligence had a significant, positive effect on the three social negotiation outcomes of trust, satisfaction, and desire to work together again in the future. Moreover, rapport and negotiation strategy either fully or partially mediated each of these relationships. In contrast, emotional intelligence had no significant effects on economic outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Negotiation is a social process through which more than two parties try to settle what each party shall give and take, or perform and receive, in order to satisfy their needs (Rubin and Brown 1975). Negotiation has been researched from several different approaches: the economic model (e.g., Sebenius 1992), through decision-making behavior (e.g., Bazerman et al. 2000), and in social psychology (e.g., Rubin and Brown 1975). Perspectives from these studies have framed various issues that play critical roles in the negotiation process (e.g., Thompson 1990a).

Historically emotion has not been highlighted in historical negotiation research. Recently researchers have begun to pay attention more to the role emotion has in negotiations. For instance, researchers have found that positive emotions lead to creative solutions (Carnevale and Isen 1986), concession making (Baron 1990), win-win agreements (Hollingshead and Carnevale 1990), satisfaction (Forgas 1998), and the desire to stay in the relationship (Lawler and Yoon 1995). Meanwhile, negative emotions in negotiations lead to more impasses, a negative impression of the opponent, and less flexibility in thinking and joint gain (Allerd 1999; Allerd et al. 1997). The ability to manage both positive and negative emotions are critical for enhanced negotiation performance, indicating that emotional intelligence would be a critical competency in this process (Fulmer and Barry 2004).

Emotional intelligence (EI) is defined as being aware of the emotions of self and others, having control over one’s own emotions, and being cognizant in the management of others’ emotions (Goleman 1995). Behavioral research attests that EI has a large impact on individual and organizational performance in areas, such as leadership effectiveness, teamwork, relationship development, academic performance, and pro-social behaviors (e.g., Mayer et al. 2004). However, little research has been done on the influence of EI on negotiations.

The purpose of the current study is to examine how the EI of negotiators influences outcomes, including economic benefits and social outcomes, such as individual and joint gain, satisfaction, trust, and the desire to work in the future. This study also aims to explore the mediating effects of rapport, bargaining strategy, and judgment accuracy on the relationship between EI and negotiation outcomes.

1.1 Emotional Intelligence

The concept of EI has attracted a great deal of attention from researchers in recent years after Goleman introduced his work entitled Emotional Intelligence in 1995. Yet, initial research on EI dates back to the 1930s. Goleman suggested that EI includes five abilities: self-control, self-awareness, motivation, social skill, and empathy. Salovey and Mayer (1990) suggested EI has three components: the appraisal and expression of emotion, the regulation of emotion, and the utilization of emotion. The appraisal and expression of emotion refers to the ability to perceive the emotions of self and others and to express emotions verbally and non-verbally. Regulation of emotion refers to the ability to maintain positive affect and avoid negative affect, and to regulate and alter the affective reactions of others. Finally, the utilization of emotion refers to the ability to engage in flexible planning, generate creative thinking, redirect attention, and motivate positive emotions.

Many scholars have researched the implication of EI on individual, group, and organizational behaviors. EI helps individuals cope successfully with environmental demands and pressures (Bar-On 1997) and provides the ability to control or redirect disruptive impulses and moods (Goleman 1998). EI is closely related to the social skills needed for teamwork (Mayer and Salovey 1997; Sjoberg 2001), such as enabling people to effectively manage relationships, build networks, and develop rapport (Goleman 1998). Similarly, Bar-On (1997) argued that EI helps group development because effective and smooth teamwork starts from knowing the strengths and weakness of others and leveraging the identified strengths. Many empirical studies have attested that EI positively relates to the quality of interactions with effective stress management (Gohm et al. 2005), customer relations (Janovics and Christiansen 2003), organizational citizenship behaviors (Carmeli and Josman 2006), organizational commitment (Giles 2001), and the performance of leaders (Nikolaou and Tsaousis 2002)

1.2 The Role of Emotions in Negotiation

Prior research has documented the importance of emotional processes in negotiation and has generally found that positive emotions play functional roles (e.g., Kumar 1997), whereas negative emotions can play dysfunctional roles (e.g., Allerd 1999). For instance, positive emotions induce negotiators to adopt creative problem-solving strategies (Carnevale and Isen 1986), which are more likely to result in integrative agreements (Kumar 1997), favorable feelings among negotiators, and more flexibility in negotiations (Druckman and Broome 1991). Additionally, positive emotions tend to reduce hostile behaviors (Baron 1990), increase concession making (Pruitt and Carnevale 1993), and promote win-win agreements (Hollingshead and Carnevale 1990).

On the contrary, negative emotions lead to an increase in negative impressions toward the opponent and causes aggressive behavior (Bell and Baron 1990). In particular, anger can cause retaliatory impulses and behavior, lead to lower joint gain, and negatively impact the desire of opponents to work together (Allerd 1999). In addition, angry negotiators are less accurate in judging the concerns of their opponent (Allerd et al. 1997). This is due to negative emotions resulting in cognitive capacity limits and attention deficits, predisposing judges toward using heuristics rather than substantive cognitive processing of the situation (Forgas 1998). Further, it has been found that negative emotions increase self-centered interests, preventing a mutually beneficial agreement to be concluded between two or more parties (Lowenstein et al. 1989).

1.3 Emotional Intelligence and Negotiation

Despite a number of studies on emotions in the negotiation process, little research has examined the specific role of EI within negotiations. Fulmer and Barry (2004) argue that EI would help negotiators more successfully manipulate emotions in both self and others and evaluate the risk associated with the negotiation more accurately, resulting in better decision-making. Foo et al. (2005) empirically tested the impact of EI on individual and dyadic gains and satisfaction with the negotiation outcome, finding that those high in EI received more joint gains and less individual gains than their counterparts.

The ability to regulate emotions is helpful in the negotiation process. For instance, negative emotions can arise during negotiation, leading to inadequate outcomes such as a reduction in joint gain or impasse (Allerd 1999; Allerd et al. 1997). Having EI allows one to detect emotional changes and the reasons for these changes (Goleman 1995). Also, EI helps to appraise the result of expressing negative emotions (Salovey and Mayer 1990; Mayer and Salovey 1997), enhancing a negotiator’s ability to avoid negative outcomes. In this manner, EI may motivate negotiators to engage in more constructive behavior.

Positive affect can be developed and retained using skills stemming from EI. This feature of EI has many implications for negotiation. For instance, positive affect may help negotiators generate creative solutions (Baron 1990; Carnevale and Isen 1986), get more concessions from opponents (Baron 1990; Pruitt and Carnevale 1993), and promote win-win agreements (Hollingshead and Carnevale 1990). Additionally, in a study by Forgas (1998), negotiators in good moods showed more satisfaction than negotiators in bad moods, and Lawler and Yoon (1995) found positive emotions enhance commitment behavior such as the desire to stay in the relationship. In sum, our study predicts that EI will be positively associated with both economic and social outcomes, despite findings by Foo et al. (2005).

-

H1a: Individual EI will have a positive association with Individual Gain.

-

H1b: Individual EI will have a positive association with the Opponent’s Trust Level.

-

H1c: Individual EI will have a positive association with the Opponent’s Negotiation Experience.

-

H1d: Individual EI will have a positive association with the Opponent’s Desire to Work in the Future.

-

H1e: Dyad Emotional Intelligence will have a positive association with Joint Gain.

In addition to these potential direct effects of EI on negotiation outcomes, the current study examined the indirect effects of EI on negotiation outcomes through rapport, negotiation strategy, and judgment accuracy.

1.4 Rapport

Rapport is defined as a dyadic or group level affective state that comes from an entrainment of affective displays; particularly nonverbal displays (Tickel-Degnen and Rosenthal 1990). Rapport is often discussed as the initial stage of relationship development (Izard 1990). When rapport is present, people come to have intensive mutual interests in what others are saying and doing and positive attitudes toward one another. Reciprocal positivity is signaled by nonverbal behaviors, such as leaning forward, having eye contact, smiling, and other gesturing. Park and Burgess (1924) described rapport as “the existence of a mutual responsiveness, such that every member of the group reacts immediately, spontaneously, and sympathetically to the sentiments and attitudes of every other member” (p. 93).

Research on the impact of rapport on negotiation performance shows that rapport would play a critical role in leading to improved negotiation outcomes such as the promotion of mutually beneficial agreements (Nadler 2007), the generation of cooperative solutions (Moore et al. 1999), and better social and economic outcomes (Drolet and Morris 2000). Even in the context of non face-to-face negotiation such as email or telephone, rapport played critical roles in the process and outcomes (Gratch et al. 2007; Nadler 2004). Developed rapport is likely to motivate negotiators to maintain relationships.

Scholars have argued that EI helps people effectively develop rapport in interpersonal relationships by building networks and developing a common ground, since EI provides people with the social skills needed for teamwork and effective communication (Goleman 1998; Mayer and Salovey 1997). A positive association between EI and successful interactions with others has been found (Jordan et al. 2002; Sjoberg 2001). Further, Lopes et al. (2003) found that emotionally intelligent people reported less negative relationships with close friends. Therefore, by using social and communication skills, EI will allow negotiators to develop better rapport with their opponents that, in turn, is likely to lead to better negotiation outcomes.

-

H2a: Dyadic Rapport (DR) will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Trust.

-

H2b: DR will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Experience.

-

H2c: DR will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Desire.

-

H2d: DR will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Joint Gain.

1.5 Negotiation Strategy

The strategy of problem solving in negotiation (sometimes labeled “cooperation”) involves an effort to find a mutually acceptable agreement or a win-win solution. Problem solving strategies help negotiators make win-win agreements, provided that there is integrative potential and the parties adopt ambitious but at the same time realistic goals (Pruitt 1983). Carnevale and Isen (1986) suggests:

the problem solving strategy uses tactics such as the exchange of truthful information about needs and priorities, and a set of tactics referred to as “trial and error,” involving 1) frequently changing one’s offer; 2) seeking the other’s reaction to each offer; 3) making larger concessions on items of lower priority; and 4) systematic concession making, where a negotiator explores various options at one level of value to himself/herself before proceeding to a lower level (p. 2).

Similarly, Pruitt and Carnevale (1993) discussed tactics that lead to an integrative agreement, such as expanding the pie, exchanging concessions, and solving underlying concerns. Expanding the pie means to reach integrative agreements that increase the available resources to ensure that both sides get what they want out of the process. Exchanging concessions is the process of yielding on issues that are low priority to self but high priority to opponent. Finally, solving underlying concerns negotiators make assumptions about their opponents’ underlying concerns and priorities and search for ways to satisfy these concerns.

Researchers have found that negotiators’ affective states have an influence on their choices of strategy. Carnevale and Isen (1986) found that negotiators who experienced positive affect were more likely to adopt problem-solving strategies, therefore achieving higher outcomes than those with negative affect. Other studies show that when negotiators experienced pleasant moods, they set higher goals and achieved better outcomes, being less likely to avoid negotiation or compete with their opponents (Baron 1990; Forgas 1998). EI, therefore, should help negotiators to develop positive emotions and avoid negative emotions, leading the negotiator to make more regular and effective use of problem solving strategies.

-

H3a: Dyadic Negotiation Strategy (DNS) will mediate the relationship between Dyadic Emotional Intelligence (EI) and Dyadic Trust.

-

H3b: DNS will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Dyadic Experience.

-

H3c: DNS will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Dyadic Desire.

-

H3d: DNS will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Joint Gain.

1.6 Judgment Accuracy

The cognitive approach to negotiation views that when negotiators have inaccurate perceptions of their opponents they are more likely to result in suboptimal or inefficient outcomes in their negotiation (Bazerman and Carroll 1987; Walton and McKersie 1965). When negotiators had accurate judgments of the opponent’s interests and priorities, they could create more values for both parties. The accurate judgment enables negotiators to discover “logrolling” solutions in which negotiators’ priorities across issues are different, but complementary (Thompson 1990b, 1991). Bazerman and Carroll (1987) showed that people who made inaccurate judgments of their opponent were less likely to reach mutually beneficial or integrative agreements. Understanding the interests of the opponent is a key factor in reaching integrative negotiation agreements (Thompson and Hastie 1990).

In the negotiation, frequently, the opponent’s interests cannot be directly perceived but rather, can be inferred on the basis of cues such as the opponent’s behavior, emotional expression, and statements. EI provides negotiators with the ability to attend to and more accurately interpret social information that the opponent expresses. Because emotional expression provides key information about the opponent’s interest in the negotiation, highly emotionally intelligent negotiators are likely to catch more accurate and richer information about underlying concerns and contextual limitations that their opponents have (Fulmer and Barry 2004). By understanding subtle cues and observing the opponent’s reactions, EI is likely to help in the detection of a more optimal offer that satisfies the opponent. Empathy, one of the features of EI, helps negotiators acquire information about the other party’s goals, values, and priorities. Some negotiators are better at empathy than others, and empathy has been shown to lead to more win-win agreements (Bazerman and Neale 1983). To summarize, due to empathy and the ability to be aware of others’ emotions, EI should help negotiators judge their opponents’ interests, which should help them to produce better negotiating outcomes.

-

H4a: Dyadic Judgment Accuracy (DJA) will mediate the relationship between Dyadic Emotional Intelligence (EI) and Dyadic Trust.

-

H4b: DJA will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Dyadic Experience.

-

H4c: DJA will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Dyadic Desire.

-

H4d: Dyadic Judgment Accuracy will mediate the relationship between Dyadic EI and Joint Gain.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Participants consisted of 284 upper-level undergraduate business students (161 men and 123 women with a mean age of 22.9 years). They reported a mean of 4.5 years of work experience (SD \(=\) 1.3), 2 years of managerial experience (SD \(=\) .25), and a grade point average of 3.09 (SD \(=\) .56). Regarding ethnicity, 70 % were White, 20 % were African American, 6 % were Hispanic, and 3 % were Asian (1 % did not report ethnicity). Participation was voluntary, in exchange for extra credit points for a course, as well as potential cash rewards. Specifically, based on individual gain scores, the top five performers received cash rewards ranging from $50 to $200, according to their ranks.

The experiment was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, EI scores were assessed using the Schutte et al. (1998) 33-item scale during a class period. The second phase involved a laboratory experiment where two participants completed a job contract negotiation. In each dyad, randomly one participant was assigned to the role of a personnel manager and the other participant was assigned to the role of the new employee. They executed the negotiation task (e.g., Thompson and DeHarpport 1994) during the next 25 min. This negotiation task included three types of negotiation issues: distributive, logrolling, and compatibility issues. For example, salary and medical coverage were distributive issues where gains for one party resulted in equal losses for the opposite party. Annual raises and vacation time were logrolling issues where gains for one party did not result in equal losses for the opposite party. The starting date was a compatible issue where gains for one person represented equal gains for the opposite party. If participants agreed on one of the options for each issue, then each participant would receive the score assigned to the option according to his or her payoff schedule (e.g., Thompson and DeHarpport 1994). After the completion of the negotiation task, the participants filled out several questionnaires, including the mediating variables of rapport, judgment accuracy, and bargaining strategy and subjective negotiation outcomes of trust, negotiation experience, and the desire to work in the future.

2.2 Measurement

Emotional intelligence EI was measured by using a 33-item scale developed by Schutte et al. (1998; \(\alpha = .87, \alpha = .92\) in the current study). This scale has been widely used in research that examines the effects of EI on a variety of behavior and performances (Mohapatra and Gupta 2010), task performance and organizational citizenship (Carmeli and Josman 2006), and customer satisfaction (Kembach and Schutte 2005). The items in this scale reflect three dimensions of EI: appraisal and expression of emotion, regulation of emotion, and utilization of emotions in solving problem. However, the scale provides only one total score of EI. The items are assessed on 5-point Likert scale.

Rapport Rapport was measured using the 5-item scale developed by Drolet and Morris (2000; \(\alpha = .83, \alpha = .73\) for this study). Factor analysis revealed that two items did not load on the designated factor, so this study dropped these two items. The questionnaire assesses how much participants feel mutual intention, positivity, and coordination with each other during the negotiation task. The items are measured on 7-point Likert-type scale.

Negotiation strategy The current study used Forgas’ (1998; \(\alpha = .60\) for this study) negotiation strategy scale that consists of two items. The scale measures what types of negotiation strategies participants used during the negotiation task. Examples of the items are, “I support his/her choices in hope that they will support mine” and “I do not support his/her choices so that mine has a better chance.” The items are answered using an 8-point bipolar scale on which “1” represents “definitely no” and “8” represents “definitely yes”.

Judgment accuracy In the current study, judgment accuracy refers to the participant’s ability to correctly discern the relative importance of each of the two logrolling issues to his or her opponent. The score is calculated using the formula developed by Thompson (1990a) and has been employed by other negotiation researches (e.g., Thompson 1991). The score of judgment accuracy was computed by examining deviations between negotiators’ estimates and the true values for the two logrolling issues. Then, the deviations were transformed to values between 0 and 1, with a value closer to 1 representing a more accurate judgment of the opponent’s interest.

Trust Trust was measured using the 12-item scale developed by Cummings and Bromiley (1996; \(\alpha = .70; \alpha = .89\) for this study). The questionnaire asks participants how much they thought their partner was honest and reliable during the negotiation. Examples of the items are, “I think that the other party told the truth in the negotiation,” and “I think that the other party met its negotiated obligations.” The items are assessed on 7-point Likert-type scales.

Negotiation experience This study adopted five items from the Negotiation Evaluation Survey (Coleman and Lim 2001; \(\alpha = .70; \alpha = .68\) for the current study). We used only three items in this study due to low reliability estimates (\(\alpha = .58\)). This scale asked participants to report on how positive or negative their emotions were during the negotiation. The items are assessed using 7-point Likert-type scale.

Desire to work together in the future The variable of the desire to work together in the future was assessed using a 2-item scale developed by Morris et al. (1999; \(\alpha = .68\) for the current study). This scale asked participants whether they would work with their opponent again if they had a chance in the future. The items are measured on 7-point Likert-type scale.

Individual and join gain If participants agreed on one of the options for each issue, then the participants would receive a score assigned to that option according to the included payoff schedule (e.g., Thompson and DeHarpport 1994). Individual gain was calculated by summing up five scores from the following possible areas: Annual raise (0–340 points), vacation (0–160 points), salary (0–300 points), medical coverage (0–500 points), and starting date (0–220 points). The maximum possible score on individual gain for both roles was 1,520 points, whereas the minimum possible score was 0 points. The joint score of each dyad was calculated by summing both participants’ individual gains. The maximum score possible was 1,700 points and minimum score possible was 1,120 points for joint gain.

3 Results

3.1 Correlation Analyses

In the current study, two levels of data—individual and dyadic—were analyzed for testing our hypotheses. A total of 284 cases (142 dyads) were usable, after dropping two missing cases. Tables 1 and 2 show the means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables at the individual and dyadic levels, respectively. Dyadic variables were calculated by averaging the scores of the participants in each negotiation, with the exception of joint gain, which was calculated by summing up the scores of each dyad.

3.2 Regression Analyses

Hypotheses H1a through H1e were examined using multiple regression analysis. The test of the hypotheses involved two steps. In step 1, only demographic variables such as gender, age, and GPA were regressed on negotiation outcomes for testing a control model. In step 2, EI was added to the control model to see whether EI explained significant variations in negotiation outcomes and over the demographic variables. Table 3 presents the results of multiple regression analyses.

Hypothesis 1a: individual EI will have a positive association with individual gainHypothesis 1a was not supported. Control model H1a showed that demographic variables did not predict individual gain (\(R^{2 }= .02, p = .44\)). When the demographic variables were controlled, the model H1a demonstrated that individual EI could not significantly explain the variance of individual gain (\(R^{2 }= .04, p = .20\)) over the demographic variables. EI was actually negatively associated with individual gain (\(\beta = -.14, p < .05\)). However, the overall model was not significant.

Hypothesis 1b: individual emotional intelligence will have a positive association with the opponent’s trust levelHypothesis 1b was marginally supported. The control model H1b showed that demographic variables did not predict the opponent’s trust (\(R^{2 }= .01, p = .56\)) significantly. When the demographic variables were controlled, the model H1b demonstrated that the addition of the EI produced a significant increase in \(R^{2}\) (from 1 to 5 %, \(F = 6.74, p < .01\)). Also, EI was a significant predictor of opponent’s trust (\(\beta = .19, p < .05\)). However, although the \(R^{2}\) change and the coefficient of EI were significant, the regression model H1b was only marginally significant (\(p = .08\)).

Hypothesis 1c: individual EI will have a positive association with the opponent’s negotiation experienceHypothesis 1c was strongly supported. The control model H1c indicated that the demographic variables were not associated with the opponent’s negotiation experience (\(R^{2 }= .02, p = .56\)). When the demographic variables were controlled, the model H1c showed that the addition of EI produced a significant increase in \(R^{2}\) (from 2 to 6 %, \(p < .01\)), indicating that EI added significant explanatory power and explained an additional 4 % of total variance in the opponent’s negotiation experience.

Hypothesis 1d: Individual EI will have a positive association with the Opponent’s Desire to Work in the Future. Hypothesis 1d was supported. The control model H1d showed that demographic variables did not significantly predict the opponent’s desire to work in the future (\(R^{2}= .01, p = .10\)). When the demographic variables were controlled, the model H1d indicated that the addition of the EI produced a significant increase in \(R^{2}\) (from 1 to 6 %, \(p < .01\)), indicating that EI added significant explanatory power and explained an additional 5 % of total variance in the opponent’s desire to work in the future.

Hypothesis 1e: Dyad EI will have a positive association with joint gain Hypothesis 1e was not supported. The control model H1e showed that the demographic variables did not significantly predict joint gain (\(R^{2}= .00, p = .93\)). When the demographic variables were controlled, the model H1e indicated that dyadic EI could not significantly explain variances in joint gain (\(R^{2}= .01, p = .84\)) over the demographic variables.

3.3 Mediation Analyses

Mediation hypotheses were tested using the multiple regression approach described by Baron and Kenny (1986). For each set of regressions, Sobel’s (1982) test was conducted to determine whether the reduction in the value of the coefficient (when controlling for the mediator) was significant. Dyadic-level scores were used in these analyses.

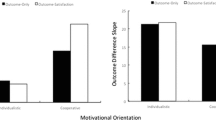

As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, both rapport and negotiation strategy were found to partially or fully mediate the relationships of EI with trust, satisfaction, and desire to work together again. Specifically, Fig. 1 shows analyses examining three potential mediating effects of rapport. In the top diagram, when controlling for rapport, the path coefficient between EI and trust was no longer significant. Thus, the relationship between EI and trust was fully mediated by rapport (Sobel test \(F = 3.71, p < .01\)), supporting Hypothesis 2a. In the middle diagram, when controlling for rapport, the relationship between EI and negotiation experience was no longer significant, indicating full mediation (Sobel test \(F = 3.57, p < .01\)) and supporting Hypothesis 2b. In the bottom diagram, when controlling for rapport, the relationship between EI and desire to work together again was significantly decreased but not eliminated, indicating partial mediation (Sobel test \(F = 3.42, p < .01\)) in support of Hypothesis 2c.

Figure 2 shows analyses examining three potential mediating effects of negotiation strategy (i.e., greater dyadic use of a cooperative, problem-solving strategy). In the top diagram, when controlling for negotiation strategy, the path coefficient between EI and trust was no longer significant. Therefore, the relationship between EI and trust was fully mediated by strategy (Sobel test \(F = 2.78, p < .01\)), supporting Hypothesis 3a. In the middle diagram, when controlling for negotiation strategy, the relationship between EI and experience was significantly reduced, indicating partial mediation (Sobel test \(F = 2.80, p < .01\)) and supporting Hypothesis 3b. In the third diagram, when controlling for negotiation strategy, the relationship between EI and desire was significantly reduced, indicating partially mediation (Sobel test \(F = 2.30, p < .05\)) and supporting Hypothesis 3c.

Regarding the relationship between EI and joint gain, for which there was no direct relationship, there was no evidence for mediating effects of either rapport or negotiation strategy, and hence no support for Hypotheses 2d and 3d. Finally, the relationships between EI and dyadic judgment accuracy was not significant (\(\beta = -.07, p = .55\)). Therefore, dyadic judgment accuracy did not mediate any relationships between EI and outcome measures, so Hypotheses 4a–d were not supported.

4 Discussion

The results showed that negotiator’s EI had a positive association with negotiation outcomes. First, negotiators who worked with emotionally intelligent opponents experienced positive emotions during negotiation, had positive impressions toward their opponents, and felt comfortable in discussing issues with their opponents. So, emotionally intelligent negotiators led their opponents to have an overall positive negotiation experience. Second, when negotiators worked with emotionally intelligent opponents, they felt that their opponents were honest, reliable, and trustful and did not try to take advantage. Third, negotiators who worked with emotionally intelligent opponents felt that they wanted to work with the same opponents in the future.

In a similar vein, our findings support the past research on EI. Numerous studies have found that EI has a close relationship with the social skills necessary for teamwork (Goleman 1998; Mayer and Salovey 1997; Sjoberg 2001) and aids in the proficiency in managing relationships and building networks (Goleman 1998). The outcome of the current study suggests that EI helps people generate positive social outcomes in a negotiation task.

Our hypotheses (H1a and H1e) were not supported. Those ranking high in EI (individual and group) did not achieve high individual and joint gains, respectively. These outcomes may be explained in several ways. First, we found that individual EI had a negative relationship with individual gain. This finding implies that those with higher emotional intelligent may have a tendency to make more concessions in order to avoid tension and to maintain positive feelings between the negotiating parties. Second, it is possible that the benefits of EI may take some time to translate into long-term joint gains. However, due to the temporal limitation of the current experimental design where participants could negotiate for a limited time, there may not have been sufficient opportunity for the impacts of higher EI to positive social relationship to create better economic outcomes.

A mediation model identifies relationships between two variables via the inclusion of a third explanatory variable, known as a mediator. The mediator serves to clarify the nature of the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable (MacKinnon 2008). From our analyses, we found that during a negotiation task emotionally intelligent negotiators demonstrate intensive mutual interests in and a positive attitude toward their opponents. Additionally, these behaviors as well as adopting a cooperative strategy rather than a contending strategy led the negotiators to develop a higher level of trust, a more favorable negotiation experience, and a stronger desire to work together in the future.

4.1 Limitations and Future Research

There are some limitations to our study that need to be addressed. First, the current study may have questionable external validity because it used a laboratory experimental design and undergraduate students as subjects. Therefore, it may be limited in generalizing its findings to other population samples that have dissimilar demographic backgrounds or different levels of negotiation experience. Second, the negotiation experience and rapport scales we used had low reliability levels in our initial analyses. However, after dropping the items that loaded poorly on the designated factor, the reliability estimates of both scales increased. Third, in measuring EI, we used a self-report questionnaire. Researchers, in the past, have criticized self-report scales, arguing that respondents could be biased about their own emotional skills (Matthews et al. 2004). Additional research should look into using extraneous sources (e.g., subordinates) for scoring EI. Finally, it should be recognized that EI explained only a small amount of the variance found in negotiation outcomes measured (i.e., trust, negotiation experience, and the desire to work beyond the current setting). Additional work will need to be explored in order explain how EI impacts various negotiation outcomes and between each sub-construct of EI.

This study revealed that rapport and negotiation strategy mediated the influence of EI on some interpersonal negotiation outcomes. Besides these mediating variables, future research needs to identify more variables that may mediate the relationships between EI and negotiation outcomes, such as perspective taking and the nature of negotiation task. Third, the current study measured the EI of individuals within dyadic groups rather than pre-assigning individuals to their dyads based on EI scores. The manipulation of dyadic assignment may provide future research with more powerful tests and clearer understandings about the effect dyadic EI has on negotiation outcomes. For example, it might be worth examining the influence of EI on negotiation among dyads that are high, low, or mixed in EI.

In this study, we provide new insights into the literature on negotiation by considering EI as an important predictor of both interpersonal dynamics and negotiation outcomes. This study discovered that EI levels during negotiation contributed to developing a high level of trust, a favorable experience, and a strong desire to work together in the future. The also results revealed that both negotiation strategy and rapport fully or partially mediated the effects of EI on multiple negotiation outcomes.

References

Allerd KG (1999) Anger and retaliation: toward an understanding of impassioned conflict in organizations. In: Bies RJ, Lewicki RJ, Sheppard BH (eds) Research on negotiation in organizations, vol 7. JAI, Greenwich, pp 27–58

Allerd KG, Mallozzi JS, Matsui F, Raia CP (1997) The influence of anger and compassion on negotiation performance. Organ Behav Human Decis Process 70:175–187

Bar-On R (1997) The emotional intelligence inventory (EQ-I): Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Baron RA (1990) Environmentally induced positive affect: its impact on self-efficacy, task performance, negotiation, and conflict. J Appl Soc Psychol 20:368–384

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personal Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Bazerman MH, Carroll JS (1987) Negotiator cognition. In: Staw BM, Cummings LL (eds) Research in organizational behavior, vol 9. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 247–288

Bazerman MH, Neale MA (1983) Heuristics in negotiation: limitations to effective dispute resolution. In: Bazerman MH, Lewicki RJ (eds) Negotiating in organizations. Sage, Beverly Hills, pp 51–67

Bazerman MH, Curhan JR, Moore DA, Valley KL (2000) Negotiation. Annu Rev Psychol 51:279–314

Bell PA, Baron RA (1990) Affect and aggression. In: Moore BS, Isen AM (eds) Affect and social behavior. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 64–88

Carmeli A, Josman ZE (2006) The relationship among emotional intelligence, task performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Human Perform 19:403–419

Carnevale PJ, Isen AM (1986) The influence of positive affect and visual access on the discovery of integrative solutions in bilateral negotiation. Organ Behav Human Decis Process 37:1–13

Coleman PT, Lim Y (2001) A systematic approach to assessing the effects of collaborative negotiation training on individuals and systems. Teachers College, Columbia University, New York

Cummings LL, Bromiley P (1996) The organizational trust inventory (OTI): development and validation. In: Kramer RM, Tyler TR (eds) Trust in organizations: Frontier of theory and research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 302–330

Drolet AL, Morris MW (2000) Rapport in conflict resolution: accounting for how nonverbal exchange fosters cooperation on mutually beneficial settlements to mixed motive conflicts. J Exp Soc Psychol 36:26–50

Druckman D, Broome BJ (1991) Value difference and conflict resolution: familiarity or liking? J Confl Resolut 35:571–593

Foo MD, Elfenbein HA, Tan HH, Aik VC (2005) Emotional intelligence and negotiation: the tension between creating and claiming value. Int J Confl Manag 15:411–429

Forgas JP (1998) On feeling good and getting your way: mood effects on negotiator, cognition and bargaining strategies. J Personal Soc Psychol 74:565–577

Fulmer IS, Barry B (2004) The smart negotiator: cognitive ability and emotional intelligence in negotiation. Int J Confl Manag 15:245–272

Giles SJS (2001) The role of supervisory emotional intelligence in direct report organizational commitment. University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Gohm CL, Corser GC, Dalsky DJ (2005) Emotional intelligence under stress: useful, unnecessary, or irrelevant? Personal Individ Differ 39:1017–1028

Goleman D (1995) Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books, New York

Goleman D (1998) What makes a leader? Harvard Bus Rev 76:93–102

Gratch J, Wang N, Gerten J, Fast G, Duffy R (2007) Creating rapport with virtual agents. Presented at the International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Paris, France

Hollingshead AB, Carnevale PJ (1990) Positive affect and decision frame in integrative bargaining: a reversal of the frame effect. Paper presented at the 50th annual meeting of the academy of management, San Francisco

Izard CE (1990) Personality, emotion expressions, and rapport. Psychol Inq 1:315–317

Janovics J, Christiansen ND (2003) Profiling new business development: personality correlates of successful ideation and implementation. Soc Behav Personal Int J 31:71–80

Jordan PJ, Ashkanasy NM, Hartel CEJ, Hooper GS (2002) Workgroup emotional intelligence: scale development and relationship to team process effectiveness and goal focus. Human Resour Manag Rev 12:195–214

Kembach S, Schutte N (2005) The impact of service provider emotional intelligence on customer satisfaction. J Serv Mark 19(7):438–444

Kumar R (1997) The role of affect in negotiation. J Appl Behav Sci 33:84–100

Lawler EJ, Yoon J (1995) Structural power and emotional processes in negotiation. In: Kramer RM, Messick DM (eds) Negotiation as social process. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 143–165

Lopes PN, Salovey P, Straus R (2003) Emotional intelligence, personality, and the perceived quality of social relationships. Personal Individ Differ 35:641–658

Lowenstein G, Thompson L, Bazerman MH (1989) Social utility and decision making in interpersonal contexts. J Personal Soc Psychol 57:426–441

MacKinnon DP (2008) Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum, New York

Matthews G, Roberts RD, Zeidner M (2004) Seven myths about emotional intelligence. Psychol Inq 15(3):179–196

Mayer JD, Salovey P (1997) What is emotional intelligence? In: Salovey P, Sluyter D (eds) Emotional development and emotional intelligence: implications for educators. Basic Books, New York

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR (2004) Emotional intelligence: theory, findings, and implications. Psychol Inq 15(3):197–215

Mohapatra M, Gupta A (2010) Relationship of emotional intelligence with work values & internal locus of control: a study of managers in a public sector organization. XIMB J Manag 7(2):1–20

Moore DA, Kurtzberg TR, Thompson L, Morris MW (1999) Long and short routes to success in electronically-mediated negotiations: group affiliations and good vibrations. Organ Behav Human Decis Process 77:22–43

Morris MW, Nadler J, Kurtzberg T, Thompson L (1999) Schmooze or lose: the effects of enriching e-mail interaction to foster rapport in a negotiation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the academy of management, Chicago

Nadler J (2007) Build rapport and better deal. Negotiation, 9–11 March

Nadler J (2004) Rapport in negotiation and conflict resolution. Marquette Law Rev 87:875–882

Nikolaou I, Tsaousis I (2002) Emotional intelligence in the workplace: exploring its effects on occupational stress and organizational commitment. Int J Organ Anal 10(4):327–342

Park RE, Burgess EW (1924) Introduction to the science of sociology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Pruitt DG (1983) Strategic choice in negotiation. Am Behav Sci 27:167–194

Pruitt DG, Carnevale PJ (1993) Negotiation in social conflict. Open University Press, Buckingham

Rubin JZ, Brown BR (1975) The social psychology of bargaining and negotiation. Academic, New York

Salovey P, Mayer JD (1990) Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Personal 9:85–211

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hall LE, Haggerty DJ, Cooper JT, Golden CJ, Dornheim L (1998) Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personal Individ Differ 25:167–177

Sebenius JK (1992) Negotiation analysis: a characterization and review. Manag Sci 38:18–38

Sjoberg L (2001) Emotional intelligence: a psychometric analysis. Eur Psychol 6:79–95

Sobel ME (1982) Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S (ed) Sociological methodology. American Sociological Association, Washington, pp 290–312

Thompson L (1990a) Negotiation behavior and outcomes: empirical evidence and theoretical issues. Psychol Bull 108:515–532

Thompson L (1990b) An examination of naive and experienced negotiators. J Personal Soc Psychol 59:82–90

Thompson L (1991) Information exchange in negotiation. J Exp Soc Psychol 27:161–179

Thompson L, Hastie R (1990) Social perception in negotiation. Organ Behav Human Decis Process 47:98–123

Thompson L, DeHarpport T (1994) Social judgment, feedback, and interpersonal learning in negotiation. Organ Behav Human Decis Process 58:327–435

Tickel-Degnen L, Rosenthal R (1990) The nature of rapport and its nonverbal correlates. Psychol Inq 1:285–293

Walton RE, McKersie RB (1965) A behavioral theory of labor negotiations. Mcgraw-Hill, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K., Cundiff, N.L. & Choi, S.B. Emotional Intelligence and Negotiation Outcomes: Mediating Effects of Rapport, Negotiation Strategy, and Judgment Accuracy. Group Decis Negot 24, 477–493 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-014-9399-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-014-9399-1