Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal tract involvement in Behçet’s disease (BD) often requires surgical intervention due to serious complications such as intestinal perforation, fistula formation, or massive bleeding.

Aim

The aims of this study were to investigate the clinical and surgical features of free bowel perforation and to determine the risk factors associated with this complication in intestinal BD patients.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of 129 patients with intestinal BD treated from September 1988 to September 2008. Among them, 33 patients had intestinal perforations and all underwent emergent or elective laparotomy.

Results

The mean age of the patients with bowel perforation was 34.8 ± 15.6 years (range 12–70 years) with a sex ratio of 2.3:1 (male:female). Twenty-seven (81.8%) patients were diagnosed with intestinal BD preoperatively, whereas six (18.2%) patients were diagnosed by pathological examination after operation. Fourteen (42.4%) patients experienced postoperative recurrence of intestinal BD and 11 (33.3%) underwent reoperation. Multivariate Cox hazard regression analysis identified younger age (≤25 years) at diagnosis (HR = 3.25; 95% CI, 1.41–7.48, p = 0.006), history of prior laparotomy (HR = 5.53; 95% CI, 2.25–13.56, p = 0.0001), and volcano-shaped intestinal ulcers (HR = 2.84; 95% CI, 1.14–7.08, p = 0.025) as independent risk factors for free bowel perforation in intestinal BD.

Conclusions

According to the results of our study, patients diagnosed with intestinal BD younger than 25 years, who had a history of prior laparotomy or volcano-shaped intestinal ulcers have an increased risk of free bowel perforation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a multisystemic vasculitic disorder of relapsing acute inflammation attacks characterized by recurrent oral ulcers, genital ulcers, uveitis, and skin lesions [1–3]. The disease also affects a variety of other organs, including joints, the nervous system, blood vessels, and the gastrointestinal system. Predominant gastrointestinal symptoms and intestinal ulcerations documented by objective measures in BD patients define “intestinal BD” [4, 5]. Intestinal BD seems to be more common in the eastern rim of Asia, including Korea and Japan, compared to eastern Mediterranean countries [1, 6]. Intestinal BD often requires radiological or surgical intervention due to frequent complications, such as massive bleeding, fistula formation, and free bowel perforation [7, 8]. Notably, bowel perforation is the most disastrous complication, necessitating emergent operation. Few studies have evaluated the characteristics or clinical courses of free bowel perforation, despite considerable case reports of this complication in intestinal BD. Therefore, the aims of this study were to evaluate the clinical features, surgical treatment, and findings of free bowel perforation and to determine the risk factors associated with development of this complication in Korean intestinal BD patients.

Materials and Methods

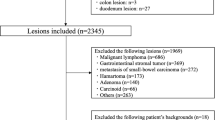

We reviewed the medical records of 129 symptomatic intestinal BD patients diagnosed and regularly followed-up at the Gastroenterology Clinic, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine between September 1988 and September 2008. Systemic BD was diagnosed according to the International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease (1990) (ISGBD) and Behçet’s Disease Research Committee of Japan (1987) [9, 10]. Intestinal BD diagnosis depended on clinical, endoscopic, radiologic, and histopathologic characteristics. Intestinal involvement of BD was assessed by colonoscopy of the large bowel and terminal ileum and radiographic modalities of the small bowel such as small bowel follow through or CT enterography in patients with systemic BD and typical gastrointestinal symptoms. Round, solitary, or a few colonic ulcers with well-demarcated borders and marginal elevation in the ileocecal area were considered as typical intestinal BD lesions (Fig. 1a, b) [11–14]. In our research, the diagnosis of intestinal BD was confirmed by the presence of systemic BD with the typical endoscopic impression suggestive of intestinal BD [15]. All of these criteria had to be satisfied to eliminate the possibility for any other intestinal diseases. We did not categorize patients as carriers of intestinal BD if there was even the slightest suggestion for Crohn’s disease (CD) or intestinal tuberculosis (TB) in any of the pathologic findings, endoscopic impressions, or extraintestinal symptoms. If we found any evidence of CD or intestinal TB during the follow-up period, we diagnosed them as CD or intestinal TB, respectively. Diagnosed or suspected CD, intestinal TB, and infectious colitis were not included in our study. To rule out CD, we excluded patients with longitudinal ulcers and ulcers with a cobblestone appearance at colonoscopic examination; characteristic perianal lesions such as fissures, fistulas, or abscesses; and pathologic findings of noncaseating granulomas [14]. Stool cultures were performed to rule out infectious colitis and a histopathologic examination ruled out caseating granulomas. The tuberculin skin test and TB polymerase chain reaction (TB PCR), as well as acid-fast bacilli staining and biopsy culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, were performed in all of the cases with suspected intestinal TB.

Patient clinical, endoscopic, and laboratory data were retrieved from a prospectively enrolled database, and the analysis was performed retrospectively. Free intestinal perforation due to BD was defined as a spontaneous penetration of the small or large intestinal wall, resulting in intestinal contents flowing into the peritoneal cavity. We investigated demographic factors, clinical symptoms, systemic manifestations, clinical BD subtype, surgical findings of intestinal perforation (location, size, and number), and postoperative outcomes (complications, recurrence, and reoperation). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Yonsei University College of Medicine.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log rank test was performed to find variables associated with free bowel perforation. The variables of interest included age at diagnosis, gender, history of prior laparotomy, BD subtype, systemic BD symptoms (oral ulcer, genital ulcer, skin and ocular lesion, joint disease), intestinal ulcer characteristics (location, shape, number, and depth), and history of certain drug use. Multivariate analysis by the Cox proportional hazards regression model including significant univariate factors (p < 0.05) determined independent risk factors. Correlation between variables and free bowel perforation is expressed as a hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Clinical Characteristics and Surgical Findings of Intestinal BD Patients with Free Bowel Perforation

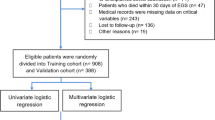

Among a total of 129 symptomatic intestinal BD patients, 33 (25.6%) patients were diagnosed with intestinal perforation and all underwent surgical resection (Fig. 2). The age at diagnosis of intestinal BD ranged from 12 to 70 years, with a mean of 34.8 years. Clinical and colonoscopic characteristics of intestinal BD patients with and without bowel perforation are summarized in Table 1. Of the 27 patients diagnosed with intestinal BD preoperatively, the duration of diagnosis until intestinal perforation was 53.1 months (range, 12–259 months). Free bowel perforation occurred within 3 years of diagnosis in 12 (44.4%) patients, between 3 and 5 years after diagnosis in six (22.2%) patients, and over 5 years after diagnosis in nine (33.3%) patients. Six patients showed free perforation as the first sign of intestinal BD with diagnosis made during surgery and confirmed pathologically.

In the surgical findings, the ileocecal area was the most frequent perforation site (17/33, 51.5%) (Table 2). Surgical inspection of the resected bowel showed diverse size and number of perforating lesions. Gross perforations were observed in 20 (60.6%) patients and multiple concurrent perforations were found in 18 (54.5%). The pathologic features of surgical specimens showed that all perforations occurred within the diseased intestinal segment. Five (15.2%) patients had a wound infection sufficiently managed by antibiotics and two (6.1%) had gastrointestinal bleeding controlled with conservative care and did not require surgical intervention. One patient died due to septic shock after operation for intestinal perforation.

Among 33 intestinal BD patients with surgical treatment for bowel perforation, the recurrence occurred most commonly at or near the anastomotic site (12/14, 85.7%) (Table 3). Among the 11 patients who required surgical reintervention, four were admitted to the hospital with intestinal reperforation. The location of all the intestinal reperforations was the ileal area near the anastomotic site. The length of resected bowel was confirmed in 27 of 33 patients. These patients underwent right hemicolectomy, ileocecectomy, or segmental small or large bowel resection. The length of resected ileum or small bowel was 40.5 ± 44.3 cm (mean ± standard deviation), ranging from 14 to 210 cm. We did not find any significant correlation between resected bowel length and recurrence/reoperation rates. In addition, we evaluated whether each medical treatment, such as colchicine, 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) or sulfasalazine, steroid, or immunomodulators, was correlated with reoperation risk in perforated intestinal BD. It was found that reoperation rates were not influenced by any certain drug use (data not shown).

Risk Factors for the Development of Free Bowel Perforation in Intestinal BD Patients

The main aim of this study was to identify risk factors associated with the development of free bowel perforation in intestinal BD patients. Therefore, Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed to compare perforation-free survival for patients classified by clinical characteristics. Univariate analysis by the Kaplan–Meier method revealed that younger age at diagnosis (≤25 years) (p = 0.002, Fig. 3a), history of prior laparotomy (p = 0.0001, Fig. 3b), steroid therapy (p = 0.035, Fig. 3c), and volcano-shaped intestinal ulcers (p = 0.001, Fig. 3d) represent significant risk factors for the development of free bowel perforation.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing free bowel perforation during the long-term follow-up in intestinal BD patients grouped according to the significant clinical risk factors. There was a significant difference in the development of free bowel perforation between the two groups according to age at diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease (BD) (≤25 years vs. >25 years) (p = 0.002) (a), history of prior laparotomy (p = 0.0001) (b), steroid therapy (p = 0.035) (c), and intestinal ulcer shape (volcano type ulcer vs. oval and geographic type ulcer) (p = 0.001) (d)

Multivariate analysis that included significant variables (p < 0.05) from univariate analysis, identified three independent risk factors associated with developing bowel perforation in intestinal BD patients; younger age (≤25 years) at diagnosis (HR = 3.25; 95% CI, 1.41–7.48, p = 0.006), history of prior laparotomy (HR = 5.53; 95% CI, 2.25–13.56, p = 0.0001), and deep, volcano-shaped ulcers (HR = 2.84; 95% CI, 1.14–7.08, p = 0.025) (Table 4).

Discussion

Oshima et al. [3] reported that over 40% of BD patients had gastrointestinal complaints, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Typical ulcerative lesions documented by objective modalities account for only 3–25% of BD patients [4, 16]. Intestinal BD can be diagnosed if a patient showed a typical ulcer in the small or large intestine, and systemic manifestations meet the diagnostic criteria of BD. However, our study population included 56 (43.4%) patients who belonged to the suspected type according to the diagnostic criteria of the Behçet’s Disease Research Committee of Japan or atypical BD according to the ISGBD criteria. We considered the patients who were classified as suspected type as having intestinal BD when typical intestinal ulcers were found on colonoscopy. The background for this diagnosis is that a considerable number of patients do not satisfy the conventional criteria of systemic BD at the initial presentation of typical intestinal ulcers but systemic symptoms may eventually develop to fulfill the complete and incomplete subtype criteria [15, 17]. Thus, we confirmed the above diagnosis of intestinal BD with repeated follow-up colonoscopy and history taking for the appearance of new systemic manifestations, bacterial cultures, and pathologic results if there was an impression of intestinal BD. Intestinal BD can cause significant morbidity and mortality due to severe complications [4, 5]. Massive hemorrhage, fistula formation, and bowel perforation occur in up to 50% of intestinal BD cases [4, 8, 18]. Free perforation can lead to panperitonitis, requiring emergent operation with a poor prognosis [4, 7, 19]. Although free perforation in intestinal BD has clinical significance, there have only been case reports or studies with small samples due to its rarity. Thus, we carried out this study not only to evaluate clinical characteristics of affected patients, but also identify risk factors associated with the development of free bowel perforation in intestinal BD patients.

In this study, the incidence of free bowel perforation in intestinal BD was considerable, which can be partly explained by our inclusion criteria. We included only symptomatic patients with intestinal BD. A considerable number of intestinal BD patients with no gastrointestinal symptoms might have been excluded. In addition, intestinal perforations may occur more commonly in Far East patients, including Koreans. Solitary, large, deep ulcers were more frequently observed in patients from this region, whereas multiple, shallow ulcers were observed in Turkish patients [20]. The ileocecal area was the most common free bowel perforation site (63.6%) which agrees with previous reports [13]. A previous study reported that all 22 perforated ulcers were in ileocecal areas (terminal ileum, ileocecal region, cecum, and ascending colon) [21].

The exact perforation mechanism in intestinal BD remains unclear, though we have considered several hypotheses. First, typical intestinal BD ulcers are usually large, discrete, and excavated. Therefore, these ulcers may penetrate, resulting in perforation [13, 14, 22]. Second, combined bowel dilatation may contribute to perforation. In CD, which is similar to intestinal BD, bowel distension with high intraluminal pressure proximal to an obstruction can increase the risk of perforation [23–25]. This hypothesis is under debate, and a considerable number of patients had bowel perforations in the absence of distension. In our study, we found only two cases of free perforation with bowel stricture or dilatation. Third, long-term steroid use may be associated with the development of bowel perforation. Sparberg et al. [26] reported that steroid therapy may develop peritonitis by inhibiting perforation sealing. However, other studies demonstrated that the incidence of steroid therapy in CD patients with bowel perforation was comparable to the overall CD population [24].

In the present study, among 33 intestinal BD patients with surgical intervention for free perforation, the recurrence rate was 42.4%. This recurrence rate seems to be much higher than medical treatment groups but similar to surgical groups, although the comparisons are relative. Kim et al. [22] demonstrated that recurrences occurred in three of 23 (13%) patients with medical treatment and eight of 16 (50%) that underwent surgery. Another investigation reported that 2-year recurrence rates were 25% after complete remission with medical treatment and 49% after surgery [27]. Choi et al. [27] showed that recurrences were more common in patients receiving an operation due to bowel perforation or fistula than patients receiving an operation for other causes. Moreover, there was no difference in the extent of bowel segment removed between cases with recurrence and those without, which coincides with our findings. In our study, all four patients developed intestinal reperforation in the ileal areas near the anastomotic site. Based on these results, wide surgical resection, which includes the normal ileum near the lesion, might be considered in treating perforated intestinal BD. Some investigators recommended that a more extensive surgical resection such as right hemicolectomy with as much as 60–100 cm of ileal resection is preferable for perforated intestinal BD [4, 21, 28]. However, such extensive surgery also poses a potential risk. Even if the operation is successful, repeated operation may be required because of the risk of recurrence in about half of the patients. Moreover, intestinal lesions of these patients tend to be localized at the ileocecal region, recur near or at the anastomotic site, and often require multiple operations that can eventually cause short bowel syndrome [28]. Thus, others suggested a more conservative approach, resecting only grossly affected bowel segments [27, 29], because there was no difference in the extent of excision between patients with recurrence and those without. To date, optimal surgical procedures and the length of normal bowel to be resected are still under debate.

To determine possible risk factors for the development of free bowel perforation in intestinal BD, we interpreted various clinical characteristics between intestinal BD patients with and without perforation. Multivariate analysis including significant variables (p < 0.05) from univariate analysis determined younger age at diagnosis, a history of surgical operation, and volcano-shaped intestinal ulcers to be independent risk factors for bowel perforation in intestinal BD patients. Our results are in accordance with several prior studies. Kasahara et al. [4] reported that the fourth decade is the most common age for intestinal BD onset. Chou et al. [21] showed the mean age of patients with perforated intestinal BD was 35.3 years. The third decade is the most frequent reported age of systemic BD onset [16, 30, 31] and the mean age is 28.8 years in Korea [32]. Early onset (≤25 years) seems to be associated with a severe disease course and frequent eye involvements [31, 33]. Based on other reports and our results, we speculate that intestinal perforations often occur in patients with early onset intestinal BD because the disease course is longer and more active.

In intestinal BD patients with a history of surgical intervention, free bowel perforation may be due to frequent postoperative recurrence and aggravation of the disease activity after surgery. Histopathologic findings often show exaggerated infiltration of inflammatory cells into anastomotic sites after invasive surgical procedures [27, 28, 34]. Recurrence adjacent to or at the anastomotic site seems to be a relatively common complication in resected intestinal BD. This phenomenon may originate from the similar pathogenesis of pathergy reaction. Naganuma et al. [34] followed 20 patients with intestinal BD, after 2 years the recurrence rate of the patients with laparotomy (75.0%) was much higher than nonsurgical patients (25.0%). Furthermore, patients that underwent surgery due to intestinal perforation or fistula had an increased risk of intestinal BD recurrence compared with patients without [27]. Thus, careful monitoring after surgery is recommended to detect postoperative recurrence or late complications.

In the present study, we did not find any drugs that were independently correlated with the development of intestinal perforation. Steroid therapy was associated with bowel perforation in univariate analysis, but there was no statistical significance in multivariate analysis. These findings might be attributed to the retrospective nature of this study in that physicians would more likely prescribe suppressive treatments more commonly to the patients with severe disease. Thus, a prospective randomized study is needed to clarify the effects of various medical treatment for intestinal BD.

In the present study, patients with volcano-shaped ulcers by colonoscopy were more likely to develop free bowel perforation. These results are in good accordance with Kim et al. [22] who reported that volcano-type ulcerations in intestinal BD showed a significantly lower remission rate for medical treatment, higher recurrence, and surgery rate compared to geographic and aphthous-type ulcerations. These grave clinical courses in intestinal BD patients with volcano-shaped ulcers may influence the frequent development of bowel perforation.

Our study has a few limitations. The number of patients was too small to reach a decisive conclusion, although it has the largest number of patients to date. In addition, we retrospectively analyzed clinical and surgical patient characteristics, although the data were prospectively enrolled. Study results could be influenced by the limitations of such an investigational design.

In conclusion, we evaluated clinical and surgical characteristics associated with free bowel perforation in intestinal BD. Based on these results, we recommend careful follow-up and intensive medical treatment to avoid severe complications such as free bowel perforation in patients diagnosed with intestinal BD younger than 25 years who had a history of prior laparotomy or volcano-shaped intestinal ulcers.

References

Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, et al. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:737–745.

Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284–1291.

Oshima Y, Shimizu T, Yokohari R, et al. Clinical studies on Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1963;22:36–45.

Kasahara Y, Tanaka S, Nishino M, Umemura H, Shiraha S, Kuyama T. Intestinal involvement in Behçet’s disease: review of 136 surgical cases in the Japanese literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:103–106.

Baba S, Maruta M, Ando K, Teramoto T, Endo I. Intestinal Behçet’s disease: report of five cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1976;19:428–440.

Chung SY, Ha HK, Kim JH, et al. Radiologic findings of Behçet syndrome involving the gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 2001;21:911–924. (discussion 924–916).

Sayek I, Aran O, Uzunalimoglu B, Hersek E. Intestinal Behçet’s disease: surgical experience in seven cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:81–83.

Ketch LL, Buerk CA, Liechty D. Surgical implications of Behçet’s disease. Arch Surg. 1980;115:759–760.

Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1656–1662.

Anonymous. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078–1080.

Mizushima Y. Revised diagnostic criteria for Behçet’s disease in 1987. Ryumachi. 1988;28:66–70.

Yao T, Matsui T, Hiwatashi N. Crohn’s disease in Japan: diagnostic criteria and epidemiology. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:S85–S93.

Lee CR, Kim WH, Cho YS, et al. Colonoscopic findings in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:243–249.

Lee SK, Kim BK, Kim TI, Kim WH. Differential diagnosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease and Crohn’s disease by colonoscopic findings. Endoscopy. 2009;41:9–16.

Cheon JH, Kim ES, Shin SJ, et al. Development and validation of novel diagnostic criteria for intestinal Behçet’s disease in Korean patients with ileocolonic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2492–2499.

Bayraktar Y, Ozaslan E, Van Thiel DH. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Behçet’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:144–154.

Jung HC, Rhee PL, Song IS, Choi KW, Kim CY. Temporal changes in the clinical type or diagnosis of Behçet’s colitis in patients with aphthoid or punched-out colonic ulcerations. J Korean Med Sci. 1991;6:313–318.

Smith JA, Siddiqui D. Intestinal Behçet’s disease presenting as a massive acute lower gastrointestinal bleed. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:517–521.

Bradbury AW, Milne AA, Murie JA. Surgical aspects of Behçet’s disease. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1712–1721.

Korman U, Cantasdemir M, Kurugoglu S, et al. Enteroclysis findings of intestinal Behçet disease: a comparative study with Crohn's disease. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:308–312.

Chou SJ, Chen VT, Jan HC, Lou MA, Liu YM. Intestinal perforations in Behçet’s disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:508–514.

Kim JS, Lim SH, Choi IJ, et al. Prediction of the clinical course of Behçet’s colitis according to macroscopic classification by colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:635–640.

Greenstein AJ, Mann D, Sachar DB, Aufses AH Jr. Free perforation in Crohn’s disease: I. A survey of 99 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:682–689.

Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Mann D, Lachman P, Heimann T, Aufses AH Jr. Spontaneous free perforation and perforated abscess in 30 patients with Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 1987;205:72–76.

Katz S, Schulman N, Levin L. Free perforation in Crohn’s disease: a report of 33 cases and review of literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:38–43.

Sparberg M, Kirsner JB. Long-term corticosteroid therapy for regional enteritis: an analysis of 58 courses in 54 patients. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11:865–880.

Choi IJ, Kim JS, Cha SD, et al. Long-term clinical course and prognostic factors in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:692–700.

Lee KS, Kim SJ, Lee BC, Yoon DS, Lee WJ, Chi HS. Surgical treatment of intestinal Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Med J. 1997;38:455–460.

Iida M, Kobayashi H, Matsumoto T, et al. Postoperative recurrence in patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:16–21.

Chajek T, Fainaru M. Behçet’s disease. Report of 41 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54:179–196.

Yazici H, Tuzun Y, Pazarli H, et al. Influence of age of onset and patient’s sex on the prevalence and severity of manifestations of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984;43:783–789.

Bang D. Treatment of Behçet’s disease. Yonsei Med J. 1997;38:401–410.

Demiroglu H, Dundar S. Effects of age, sex, and initial presentation on the clinical course of Behçet’s syndrome. South Med J. 1997;90:567.

Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Inoue N, et al. Analysis of clinical course and long-term prognosis of surgical and nonsurgical patients with intestinal Behçet’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2848–2851.

Conflict of interest disclosure

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to disclose.

Declaration of funding interests

None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moon, C.M., Cheon, J.H., Shin, J.K. et al. Prediction of Free Bowel Perforation in Patients with Intestinal Behçet’s Disease Using Clinical and Colonoscopic Findings. Dig Dis Sci 55, 2904–2911 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-1095-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-009-1095-7