Abstract

A recent literature explores how domestic institutions affect politicians’ incentives to enter into international agreements (IAs). We contribute to this field by systematically testing the impact of a broad set of domestic institutional design features. This allows us to compare new and established political economy explanations of IA entry. For this purpose, 99 democracies are analyzed over the period 1975–2010. We find that domestic institutions determine countries’ disposition to enter into IAs, as predicted by political economic theory. For example, democracies with majoritarian electoral institutions are less likely to conclude IAs than other democracies. Countries also conclude more IAs when their democratic institutions are long-lived and they lack an independent judiciary. However, programmatic parties and the number of domestic veto players are not associated with IA-making. The key take-away of this study is that specific domestic institutions matter for how frequently states make formal deals with each other.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Meeting the great challenges of our time, such as climate change, financial crises, and epidemics, requires collaboration among nation-states. Given that international treaties are the single most important instrument for orchestrating international collaboration, it is puzzling how little we know about why some states engage more frequently in their conclusion than others. International treaties are binding formal international agreements (IAs)—as opposed to soft law—and they are the primary instrument for international legal commitment and cooperation. More than 60,000 treaties have been registered with the United Nations (Hollis 2012), but, to date, only few empirical studies explore the conclusion of IAs in a comprehensive and systematic fashion. Nonetheless, the extant literature has taken important steps in demonstrating the importance of domestic institutions for differences in the probability of IA entry (Dreher and Lang 2016 is a recent survey of the political economy of international collaboration).

A number of these studies have dealt with the conclusion of IAs in particular policy areas. An early wave of econometric studies suggests that the civil and political freedoms enjoyed by the population of different countries can affect participation in international environmental agreements (Congleton 1992; Murdoch and Sandler 1997; Murdoch et al. 1997; Fredriksson and Gaston 2000). Also original theoretical contributions emerged from this early literature. Congleton (1992), for example, formulates the incentives of autocrats (relative to those of the median voter in a democracy) to submit to international environmental regulation. He argues that an autocrat’s grip on power is typically fragile, which translates into a high time discount rate and a reduced willingness to join efforts to protect the environment, which are of a long term nature (see Imhof et al. 2016 for the relevance of time preferences for environmental protection on the constitutional level). Congleton further argues that autocrats appropriate a larger share of a nation’s income. Insofar as environmental rules put constraints on national income growth, they would come at a high price for autocrats. But, and this introduces ambiguity, the autocratic elite appropriating a larger share of the national income might imply an increased demand for environmental protection (assuming that a clean environment is a normal good). Congleton’s results, however, support the arguments which link autocracy to less demand for environmental protection. He finds that democratic countries are, after controlling for a range of other variables, more likely to sign the 1985 Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. More recent research shows that democracies have entered some widely adhered to environmental agreements earlier than non-democracies. These include the United Nations Framework Climate Change Convention (Fredriksson and Gaston 2000), the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (Neumayer 2002).

Bernauer et al. (2010) investigate the accessions to 255 multilateral environmental treaties and assess the importance of different facets of democracy. They show that the “civil liberties” dimension of democracy is a crucial feature for the conclusion of treaties. Spilker and Koubi (2016) study the behavior of 162 states with respect to entering into 220 multilateral environmental treaties. They conclude that a supermajority requirement for legislative approval deters treaty entry, which demonstrates that constitutional requirements for entering into treaties can be of consequence. Alcañiz (2012) finds that new democracies are more likely to enter into multinational security agreements than both autocracies and older democracies, arguably because these commitments decrease the risk of authoritarian backsliding.

Another strand of early contributions by economists improved our understanding of why countries participate in trade agreements. This research tries to ascertain under which conditions politicians from different countries agree to conclude treaties to exchange market access (Grossman 2016 provides a valuable survey). The underlying assumption in this field of research is that politicians are tempted to provide their constituents and campaign contributing interest groups with protection from international competition (see, e.g., Grossman and Helpman 1994). A trade agreement becomes viable if involved governments agree on a set of mutual concessions that at least preserves the overall level of political support each of them enjoys. A particular government is more likely to join a trade agreement if it can be expected to generate substantial welfare gains for the average voter, whereas adversely affected interest groups fail to coordinate their efforts—or if the trade agreement “would create profit gains for actual or potential exporters in excess of the losses that would be suffered by import-competing industries, plus the political cost of any welfare harm that might be inflicted on the average voter” (Grossman and Helpman 1995: 687).

Inspired by economists’ political-economic models of trade policy, Mansfield et al. (2002) empirically study the effect of political regime type on the formation of preferential trade agreements (PTAs). They find that democracies are more likely than autocracies to enter into PTAs. The authors report that—holding constant other political and economic factors—pairs of democratic countries are about twice as likely to conclude a PTA as are mixed pairs and roughly four times as likely as are pairs of autocratic countries. Mansfield et al. explain this result by positing that the domestic political gains from entering into an agreement matter only to governments facing a risk of electoral punishment. Copelovitch and Ohls (2012) study the GATT/WTO accession of former colonies of existing GATT members. These were offered quick and simplified accession, but how long it took them to accept this offer and if they made use of it at all varied greatly.

Aside from these studies, which focus on the cooperation between states in one specific policy area, some authors have analyzed treaty-making across policy fields. For example, Ginsburg (2009) explores how the concentration of political authority affects the propensity of states to enter into IAs of any kind. Ginsburg finds that divided authority at the domestic level—as exemplified by bicameral or federal states—favors the conclusion of IAs. He argues that in states where authority is already divided at the domestic level, there is an incentive to add further international constraints, for example, in order to deal with disputes between different domestic holders of authority. Milewicz and Elsig (2014) study entry into 76 multilateral treaties covering a diverse set of issues. They find that new democracies conclude these multilateral agreements faster than other regimes, particularly when they are located in Europe.

The articles discussed above have made some progress toward explaining IA entry, but many questions remain unanswered: especially whether results on subject area-specific IA conclusion can be generalized to a broader set of IAs and which theories regarding the role of domestic institutions find support in the data when alternative hypotheses are tested against each other. The present article begins to fill these gaps. It tests both new and established theories on the relevance of domestic institutions for the conclusion of international agreements. This is the first time that these different hypotheses are tested against each other and some of them have not even been tested before. Our main goal is to explore how the incentives of politicians are conditioned by the type of democratic institutions under which they operate. This study is, hence, linked to Voigt and Salzberger (2002), who discuss how constitutional structure may affect the delegation of competences to domestic and international bodies.

For this purpose we study treaty-making in a sample of 99 democracies, selected according to the regime classification by Cheibub et al. (2010). We focus on democratic regimes to make sure that political decision-making takes place in a comparable setting. In that respect we are following Persson and Tabellini (2003) study on how institutional differences across democracies determine political outcomes. Our study further builds on and extends the work of Ginsburg (2009) and others who have tested general theories of IA entry without distinguishing between types of agreements. While such a general analysis provides a better understanding of broad patterns in international law-making, future studies should complement our analysis and deepen our understanding by focusing their attention on specific types of treaties and differences between these types of treaties. Only the combination of these approaches can give a full picture of what drives international law-making.

Applying a random effects negative binomial estimator to our panel dataset for the period 1975–2010, we find that, first, majoritarian electoral institutions are associated with less IAs being concluded. This indicates that IAs do not help to cater to geographically circumscribed constituencies, which majoritarian systems incentivize politicians to do. Second, we provide some evidence that countries enter into fewer IAs when their constitutions give more actors the competence to revoke them. Third, we find that countries with very low levels of judicial independence depend more on the conclusion of IAs. Improving the independence of a country’s judiciary, at least up to a certain level, thus, results in fewer IAs being concluded. Finally, programmatic parties and the number of domestic veto players appear not to be significantly associated with the conclusion of IAs.

In the following section, we present domestic political economy explanations for the conclusion of IAs. In Sect. 3, we present our dataset and the estimation approach. The regression results are discussed in Sect. 4 in light of previous findings and our own theoretical conjectures. Section 5 concludes.

2 Domestic institutions and international agreements

2.1 Rational choice of international agreements

General theories on IA formation can be grouped into two categories: unitary actor models and domestic political economy models. In the first approach states are modeled as self-interested unitary actors who conclude IAs to formalize agreed upon solutions in games of coordination and cooperation. In this literature IAs are compared to contracts in the domestic context. For proponents of this perspective IA enforcement is imperfect, but possible in repeated interactions through reputation, reciprocity or retaliation (Guzman 2008). IAs are concluded primarily to make the terms of the deal precise, to create focal points in the case of multiple equilibria, to allow states to signal their reliability to other states, and to make use of the default rules formulated in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Parisi and Pi 2016).Footnote 1 In addition, IAs can serve as the foundational text for the creation of secretariats or international organizations, which can be assigned a monitoring function to assist in sustaining cooperative equilibria (Keohane 1984). The strength of this approach is that it makes IA-making more tractable by assuming that states are the relevant unit of observation. This comes at a cost, as it disregards the specific domestic actors who are taking the decisions in IA-making.

Another branch of contributions focuses on domestic political economy considerations to address the shortcomings of the unitary actor approach by incorporating strategically thinking domestic actors (see, e.g., Milner 1997; Maggi and Rodriguez-Clare 1998). From this perspective politicians conclude IAs when it serves their interest, for example by allowing them to deal with commitment problems, political stalemate, the disproportionate influence of organized interests, information asymmetries between politicians and the electorate, and the reversibility of policies (Moravcsik 2000; Voigt and Salzberger 2002; Milner et al. 2004; Johns and Rosendorff 2009; Baccini and Urpelainen 2014). The domestic political economy approach adds a new theoretical foundation for IA-making, which is based on strategic choices and interactions of individuals given their institutional constraints. While unitary actor models explain the rationale and limits of IA-making in light of the lack of centralized enforcement at the international level, domestic political economy models supplement unitary actor theories with agent-based explanations of IA-making and can probably better explain the timing and frequency of IA-making by individual states. In the following, we adopt the domestic political economy perspective to study IA entry.

2.2 Electoral institutions and international agreements

The impact of electoral institutions on policy choices is a topic of recent research. One of the important insights of this research is that a country’s electoral system—for example, a majoritarian system like in the United States or a proportional representation (PR) system like in Israel—has considerable distributional consequences. Theoretical and empirical work (see, e.g., Persson and Tabellini 2000, 2003) relates the design of electoral institutions to the propensity of the political system to provide either more public goods or more benefits targeted to narrow groups. The key result is that PR systems tend to spend a larger share of their budget on public goods (Milesi-Ferretti et al. 2002; Persson and Tabellini 2004; Gagliarducci et al. 2011; Funk and Gathmann 2013). The theoretical explanation for these results is that politicians have different optimal reelection strategies depending on the type of electoral system under which they run for office. Competing political parties tend to need a higher share of the total vote to win under PR systems than under majority systems (Lizzeri and Persico 2001). As a result, politicians in a PR system have an incentive to allocate spending more broadly among the population; while in a majority system politicians’ optimal strategy is to garner the support of a more limited number of voters, merely sufficient to win a district. Because the competing parties are usually certain to win a number of districts each, they will strategically target resources to the remaining marginal or swing districts in which the outcome of the election is uncertain (Persson and Tabellini 2000, ch. 8).

In line with Phelan (2011) and Rickard (2010), democracies with PR are expected to rely more frequently on international agreements. Concluding IAs for the provision of public goods fits better into the electoral calculus of governments in countries with PR systems, since politicians need the votes of a larger share of the electorate to win an election. It is suggested here that IA-making comes closer to public good provision than to clientelistic targeting for two reasons (see also Setear 1996; Sandler 2008; Barrett 1999). First, IA-making is costly and the institution building that often comes with it adds to global order and stability. Countries would rather free ride on others’ efforts to advance this international public good (Ostrom 1990: 42; Gourevitch 1999; Kosfeld et al. 2009). Second, as far as the output of IA-making is concerned, numerous IAs are used to cope with externalities where activities in one state negatively affect other states (Sykes 2007; Sandler 2008). Reigning in such negative external effects produces benefits for broad groups of voters in the participating countries, which makes IA-making resemble rather public good production than the production of clientelistic benefits. Possibly certain IAs fit this characterization better than others, but most IAs are concluded to manage externalities, coordinate regulatory efforts, orchestrate security alliances, manage diplomatic relations, and communicate support for certain values. These efforts pursued with the help of IAs do not always turn out a success. Nonetheless, they do not fit well in the clientelistic benefit category; other legal instruments would be more suitable for vote-seeking through pork barrel politics. Taken together, these arguments lead to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1

Democracies with majoritarian electoral systems are less likely to enter into IAs than other democracies.

2.3 Programmatic parties and international agreements

Elections are not the only way of holding politicians accountable in a democracy. Another important aspect of the political system that influences politicians’ behavior is the organization of political parties or, more specifically, the presence of programmatic parties in the legislature (see, e.g., Cruz and Keefer 2015; Keefer 2015). These parties are characterized by a programmatic policy stance. In contrast to patron-client parties, programmatic parties are able and incentivized to discipline politicians, leading to significantly different policy choices (Keefer 2011). The prevalence of such parties in a country is operationalized here based on the ideological stance of a country’s main political parties on economic policy, or the lack thereof.

The literature identifies two important effects of programmatic parties. First, programmatic parties favor policies that emphasize public good provision over narrow political transfers (Keefer 2015). This is because programmatic parties have the organizational means to accomplish successful intra-party collective action, which, in turn, allows them to credibly commit to policies intended to benefit broad groups of voters, and thus pursuing such policies becomes the most promising electoral strategy for this type of party. How do these political incentives relate to entry into IAs? IAs are arguably less suitable for targeting political favors at narrow groups of voters. IAs, thus, tend not to benefit patron-client parties and should be concluded more often in systems where programmatic parties play a bigger role.

As for their second effect, programmatic parties tend to have a relatively longer time horizon and suffer fewer problems related to time inconsistent preferences (Voigt and Salzberger 2002). Programmatic parties are likely to outlive their members’ political careers. If such a party is run by politicians at different points in their career, overlapping generations coexist, creating incentives to safeguard against shortsighted politics. In other words, the party, as a persistent organization, finds itself playing an infinitely repeated game in which its reputation becomes important (Brennan and Kliemt 1994). These features make countries governed by programmatic parties more attractive partners for the conclusion of IAs and governing programmatic parties should be more interested in engaging in multilateral problem-solving activities that require prolonged cooperation. Hence, we expect that IA entry is more likely when programmatic parties are more prevalent.

Hypothesis 2

Democracies in which programmatic parties play a larger role are more likely to enter into IAs.

2.4 Domestic political constraints and international agreements

How institutional constraints on government affect political decision-making has been a question of particular prominence in the political economy literature ever since the seminal work of North and Weingast (1989). Their work and literature on the separation of powers show how institutional solutions arose to cope with the “dilemma of the strong state.”Footnote 2 Some scholarly contributions discuss the tradeoff in democracies between a stable policy environment (more likely with constrained governments) and being able to pass necessary reforms in response to rapidly changing economic conditions (more likely with less constrained governments).Footnote 3 In the following we discuss

-

(I)

how domestic constraints make IA conclusion less appealing for governments and therefore less likely (domestic constraints substitute for international constraints), and

-

(II)

how domestic constraints create incentives to enter into IAs (domestic constraints complement international constraints).

Each of these perspectives makes a different assumption as to which of two problems is the most crucial domestic political problem faced by governments: lack of credibility or inability to reform. First, where a government lacks credibility, joining an IA is intended to signal that the government’s hands are tied. Second, if a government is not able to pass reforms due to opposition from domestic veto players, the motive for acceding to IAs is to enhance the government’s bargaining leverage vis-à-vis the veto players. In both cases, governments conclude IAs because they help them achieving a domestic policy goal—even if the underlying motive for IA entry differs in each case. These two arguments call for empirical testing to determine which mechanism is more influential. Importantly, the two views lead to opposite predictions with respect to whether additional political constraints decrease or increase the frequency with which treaties are concluded. To clarify the reasons behind this discrepancy, we next discuss the two perspectives in more detail.

2.4.1 Credible commitment and policy reversal

The first perspective assumes that providing a stable and predictable domestic policy environment is of importance to countries striving to promote economic activity and spur development. Governments want the public to perceive laws and policies as credible and safe against opportunistic reversal. If policy changes are supplemented by corresponding IAs, the violation of which would be costly, they become more credible in the eye of the public. Unconstrained governments have severe credibility problems and the additional credibility conferred by IAs is a valuable asset, thus making it more likely that these governments enter into an agreement (Snidal and Thompson 2003; Drezner 2003; Fang and Owen 2011).

Policies can be reversed in two ways: by the current government or by future governments. In both cases, lack of domestic constraints makes policy reversal easier. In the first case, the current government opportunistically reverses its own polices at a later point in time. The main reason for lack of credible commitment resulting from this possibility is the extensively researched problem of time inconsistency, which applies to a wide range of policy areas. Whenever citizens recognize that governments are tempted and have the possibility to reverse policies to their own benefit, the citizens will not adjust their behavior to those policies in the first place. Politicians would be better off if they could send a costly signal making their policies credible. Embedding policies in IAs is an attractive option for governments with a severe credibility problem, that is, those governments lacking domestic political constraints on executive discretion. If violation of an IA is punished with reputational and monetary sanctions, its conclusion can serve as a costly signal from the government. In the second case, policy reversal occurs after a change in government. Domestic political constraints play a role here preventing excessively large and potentially destabilizing policy swings following a change in government. A government does not only need to signal voters that its policies are credible while it holds office, but also that they will remain so after its term has ended (Moe 1990). Both goals are achieved by making policy reversal more difficult.

Hypothesis 3a

As the number of domestic political constraints increases, countries are less likely to enter into IAs.

2.4.2 Overcoming domestic opposition

The second perspective, the “overcome the opposition” argument, predicts that there should be a complementary relationship between domestic political constraints and IA-making. Here, the domestic political problem is of a different nature, namely, the inability to reform. The underlying assumption is that democracies with their numerous institutional obstacles to passing reforms find it increasingly difficult to adapt to a rapidly changing environment. Under these conditions, governments seek to enter into IAs for a reason other than to enhance their credibility. Governments conclude IAs so as to bypass politically constraining actors. Heavily constrained governments can submit to international constraints in order to increase their bargaining power vis-à-vis reform-opposing veto players at home (Nzelibe 2011). As a result, numerous domestic political constraints and a high propensity to enter into IAs are expected to go hand in hand. Essentially, this is an adaptation of an original argument presented by Vaubel (1986).

This argument was also proposed by Vreeland (2003, 2007) to explain why states enter into loan agreements with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Such agreements are usually accompanied by conditions, and Vreeland argues that these conditions can be used by the political leadership to overcome domestic veto players. Referring to Putnam’s (1988) two-level game, Vreeland suggests that the government uses international-level constraints as leverage against domestic veto players. The government can enter into an IMF loan agreement without the consent of reform-obstructive veto players; however, the IMF loan imposes conditions that demand reforms very similar to those the government wanted to enact in the first place. Reneging on the conditions after having entered into the IMF agreement is costly for the government and for the veto players that oppose the reforms. Thus, there is a good chance that the veto players agree to the reforms, since opposing them at this stage could be too costly.Footnote 4 Vreeland’s argument focuses on a specific type of agreement between a government and an international organization (i.e., a loan agreement). The question is whether the same “overcome the opposition” tactic can be generalized to other IAs. The strategy should work whenever the government has greater leeway vis-à-vis veto players in regard to entering into an IA than it has in enacting new legislation on the same policy issue at the domestic level.Footnote 5 Additionally, this argument has explanatory power only when reneging on IAs is costly for veto players, which puts pressure on them to accept the content of the IA. Voigt (2012) makes a similar argument regarding the use of soft law by the US executive to circumvent checks from Congress and thus shift political power in the executive’s direction.

Based on these notions about how executives devise strategies to deal with opposition by veto players, we arrive at the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3b

As the number of domestic political constraints increases, countries are more likely to enter into IAs.

2.4.3 Judicial independence

An independent judiciary has been demonstrated to be an exceptionally effective domestic political constraint (Feld and Voigt 2003; Padovano et al. 2003; Voigt et al. 2015). A government might intentionally create a strong and independent judiciary in an effort to make its own promises, for example, the protection of private property, more credible. This idea is in line with empirical evidence showing that constitutional property rights lead to higher growth rates only when there is an independent judiciary to enforce them (Voigt and Gutmann 2013). Thus—extending the argument made above regarding credible commitments—countries without an independent judiciary might use international agreements to bind themselves vis-à-vis other governments and foreign investors. For example, BITs with arbitration clauses are a way of circumventing an overly dependent domestic judiciary. Also, non-sincere conclusion of IAs is cheaper and thus more attractive when there is no independent judiciary that could enforce an IA against the government. The negative effect of judicial independence on IA-making, however, is not necessarily linear. Countries with a level of judicial independence high enough that IAs are not needed as substitutes for national legislation will not further reduce the number of agreements they conclude in the event that their judiciary becomes even more independent. We formulate the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4

Countries with a more independent judiciary are less likely to enter into IAs.

2.5 Constitutional provisions on international agreements

To this point, our explanations of the differential IA conclusion behavior of countries have focused on general characteristics of the political system. However, there is a more proximate cause, and one that has been largely neglected in the empirical literature—constitutional rules. A country’s constitution may contain provisions relating to international agreements. Constitutions contain many rules that are potentially relevant for the production of international law, but there are two sets of rules that have a particularly clear relevance for a country’s propensity to enter into an IA. The first set of rules defines who has the power to initiate or approve IAs. The more actors there are who have the competence to initiate the negotiation of an international agreement, the more IAs should be employed as a political instrument. In contrast, the higher the number of political actors who have to approve the conclusion of an international agreement, the less frequently should IAs be concluded. This idea is in line with Spilker and Koubi’s (2016) finding regarding supermajority requirements in the legislature. The second set of rules concerns withdrawal from IAs. As discussed above, the efficacy of IAs as a commitment mechanism crucially depends on the costliness of violating the agreement or of exiting it altogether. Yet, actors will be more willing to enter into an agreement if it is possible to exit it at a later stage, thus preserving a certain degree of flexibility (Helfer 2005). It can thus be conjectured that having a higher number of actors with the competence to withdraw from an IA will lead to more IAs being entered into in the first place.

Hypotheses 5–7

Countries (a) in which the constitution allows more actors to initiate IAs, (b) in which the approval of fewer actors is required for the IA to become effective, and (c) in which more actors have the competence to withdraw from a treaty can be expected to conclude more IAs.

3 Data and estimation approach

Our dependent variable is based on a component of the KOF Index of Globalization. For this indicator Dreher et al. (2008) count the number of IAs a state has concluded annually, based on data from the UN Treaty Collection. The dataset includes all treaties signed and ratified since 1945, as long as they are deposited in the Office of the Secretary-General of the United Nations. Article 102 of the UN Charter obliges all member states to register their international treaties with the Secretariat. A treaty is defined as any document signed between two or more states and ratified by the highest legislative body of each country. We use the first difference of this variable as the number of new agreements a state enters into in a given year. This indicator comprises non-negative count data, covers the period between 1975 and 2010, and takes on values between 0 and 123. On average, a country enters into 5.5 new international agreements every year. We follow the empirical literature on the economic effects of constitutions (see, e.g., Persson and Tabellini 2003) and exclude all nondemocratic country-years according to the annual classification by Cheibub et al. (2010). Also countries that were temporarily nondemocratic after 1975 are, thus, represented in the analysis based on years in which they were democratic. The data source for our dependent variable does not allow us to distinguish between the conclusion of bilateral and multilateral treaties or treaties dealing with different policy areas. This variation in the breadth and coverage of treaties should be the subject of future research, but is outside the scope of the current article. Here we focus on testing alternative domestic political economy theories against each other to explain the overall propensity of countries to conclude IAs. Previous studies have either focused exclusively on specific types of agreements, like Spilker and Koubi (2016) who use only environmental agreements, or they have pooled all kinds of IAs, as in the case of Ginsburg (2009). We follow the latter approach.

As explained in the theory section of this article, we are interested in the relevance of a number of (rather) time-invariant country characteristics for the conclusion of agreements. The use of a (conditional) fixed effects model would not allow us to draw inferences on the effects of these country characteristics. Hence, we estimate random effects negative binomial regressions, which allow for a gamma-distributed country-specific intercept that is uncorrelated with our independent variables (Hausman et al. 1984). The random effects negative binomial regression model is given by:

In this case, X is the vector of independent variables and we seek to estimate the corresponding vector of coefficients β by maximum likelihood estimation. The dispersion parameter δ is allowed to vary randomly across groups. It is assumed that \(\frac{1}{{1 + \delta_{i} }}\sim Beta\left( {r,s} \right)\).Footnote 6

To test our hypotheses, we are interested in seven indicators. First, we use a dummy variable created by Bormann and Golder that indicates whether a country has a majoritarian electoral system. We follow Persson and Tabellini (2003, 2004) and large parts of the literature in how we construct this binary variable. Majoritarian systems are those relying exclusively on plurality rule, whereas mixed and proportional representation electoral systems are the reference category. Persson and Tabellini (2003) argue that majoritarian electoral systems are a more clearly distinct category when compared to both hybrid and proportional representation electoral systems.

Second, we construct a measure of the prevalence of programmatic parties in a political system using data from Beck et al. (2001) and following the description by Keefer (2011). This indicator reflects the share of major government and opposition parties in parliament, which have a left, right or centrist orientation in economic policies, as opposed to those without a stance on these issues. Third, to measure domestic political constraints, we draw on the number of checks and balances counted by Beck et al. (2001) in its original scale and alternatively as a dichotomized indicator. As another alternative, we use two measures of institutional policy constraints by Henisz (2000, 2002). We include these four indicators one at a time in our model specification to ensure the robustness of our empirical results.

The fourth concept in need of measurement is judicial independence for which we use a latent indicator created by Linzer and Staton (2015). This is a continuous variable constructed from various established indicators with higher values reflective of a more independent judiciary. Finally, we have constructed three indicators that count the number of actors with the constitutionally entrenched competence to (1) initiate, (2) approve, or (3) revoke IAs. Data on this come from the Comparative Constitutions Project by Elkins et al. (2009). The correlation matrix in Appendix of Table 5 shows that the correlations between most of our explanatory variables of interest are rather low.

We also include some standard control variables from the literature in our baseline model. We control for the stock of international agreements a country was party to at the end of the preceding year (i.e. in t − 1), which may account for path dependencies or saturation effects in the conclusion of treaties. In terms of socioeconomic characteristics, we account for a country’s log-population size, its log-per capita income, and its log-openness to trade. To control for basic characteristics of the political system we further include a dummy variable by Cheibub et al. (2010) for a presidential form of government, which makes parliamentary and mixed democracies the omitted category. Again, this is in line with the empirical setup of Persson and Tabellini (2003). We further control for the level of democracy using Marshall et al.’s (2014) combined polity scale, polity2. Another indicator counts the log-number of years since a country became democratic. Finally, we add a dummy variable that identifies countries with a common-law legal tradition, an indicator for aid dependence, a linear time trend, three decade fixed effects, and six regional fixed effects with eastern European and post-Soviet Union countries as the omitted category. Table 1 provides summary statistics for all indicators in our dataset and Appendix of Table 3 gives descriptions of the indicators and their data sources. Appendix of Table 4 lists the 99 countries comprising our sample.

4 Empirical results

Table 2 sets out the regression results. We report incidence rate ratios to facilitate the interpretation of the results. Ratios smaller than one indicate a negative association and ratios larger than one a positive association with the dependent variable. A likelihood ratio test (result not displayed) indicates that there is considerable overdispersion in our dependent variable, which supports our choice of the negative binomial regression model. Column 1 is our baseline model specification and includes only a set of standard control variables. We find that socioeconomic country characteristics are important predictors of a country’s conclusion of IAs. As would be expected, countries conclude more agreements when they have a larger population and more foreign trade. Countries with extensive foreign trade have more specialized economic systems and also tend to be more politically integrated, implying the conclusion of more IAs. Countries with a larger population can benefit from economies of scale in regulation, which should extend to their propensity to join international regulatory efforts (Mulligan and Shleifer 2005). Furthermore, countries dependent on aid and with weaker or only recently established democratic institutions are less able or willing to conclude IAs. These effects are robust throughout all model specifications. A country’s income per capita, its legal origin, and its form of government have no robust or statistically significant effect on the number of IAs concluded.

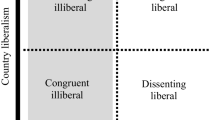

The specification in Column 2 of Table 2 adds the variables we use to test our hypotheses en bloc. Appendix of Table 6 shows that adding the indicators individually leads to identical results. This suggests no major problems with collinearity, although we test a number of hypotheses on the effects of domestic institutions.Footnote 7 In Columns 3–6 we alternate between indicators for the number of veto players in the political process. Our results consistently show that countries with majoritarian electoral institutions and where more actors have the competence to revoke international agreements conclude fewer international agreements, although the latter association is only significant at the 10% level. The result for judicial independence is more difficult to interpret, as we allow the indicator to exert a nonlinear effect. Correct interpretation thus presupposes the calculation of marginal effects and corresponding standard errors (Brambor et al. 2006). Figure 1 plots the marginal effect of increasing judicial independence at different levels of independence. Where judicial independence is low and a country increases the independence of judges, this increase is associated with fewer IAs being concluded. However, as soon as judicial independence reaches a level of about 0.6, making judges even more independent has no statistically significant effect anymore (judged by a 5%-significance level). We find no effect of programmatic parties on the propensity to conclude agreements. Also, the number of actors with the competence to initiate or approve international treaties is of no consequence.

Marginal effect of judicial independence on the conclusion of IAs. Note average marginal effect (solid line) at different levels of judicial independence (horizontal axis), estimates as in model (2) in Table 2; dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval based on the delta method

The finding that majoritarian electoral systems lead to less international cooperation in the form of IAs is very much in line with standard public choice theories on the effects of electoral institutions. Moreover, this result indicates that domestic political institutions are important for understanding state behavior in the field of international law. States’ choices on the international level are ultimately determined by the interests of national politicians and voters. The result that electoral systems have important consequences for government policies, whereas the form of government is inconsequential is very much in line with the empirical findings of Blume et al. (2009) who replicate and extend the original study by Persson and Tabellini (2003) on the economic effects of constitutions and come to the same conclusion.

We find no compelling evidence that domestic political constraints (as measured by Henisz 2000, 2002 or Beck et al. 2001) affect the propensity to conclude IAs. Among the four alternative measures we use, only one is marginally significant at the 10% level. One possible explanation for the lack of a stronger result is that the two competing arguments—unconstrained executives wanting to bolster their credibility and constrained governments wishing to overcome reform-opposing veto players—might cancel each other. Note that this finding is in contrast to Ginsburg’s (2009) results, which indicate that domestic political power sharing positively affects treaty-making activity. One reason for these contrasting results could be that Ginsburg emphasizes more structural and durable indicators of power sharing—federalism and bicameralism—whereas we focus on more encompassing and time-variant constraints on the executive, measures that better reflect our particular theoretical concerns with respect to executive credibility and political gridlock. However, our result that the absence of an independent judiciary promotes the conclusion of IAs is in direct conflict with Ginsburg’s (2009) conjecture that domestic power sharing induces treaty-making. This result rather supports the credibility enhancement motive for concluding IAs.

The weakly statistically significant evidence that constitutional competences to revoke IAs lead to less treaties being concluded contradicts Helfer’s (2005) theoretical conjecture that easier exit from an agreement would lead to more extensive international commitments and more IAs being concluded. Neither do we find support for another proposition in the literature, namely, that new democracies are more likely to conclude IAs. The logic behind this claim, which is empirically supported by the results of Alcañiz (2012) with respect to security treaties, is that young democracies are eager to solidify the new state of affairs and prevent a reversal of democratic reforms. In contrast, we find that it is the longer-lived democracies that are more likely to enter into international agreements.

Taken together, our empirical results only lend clear support to two of our seven hypotheses. These are hypothesis 1 on the effects of the electoral system and hypothesis 4 on the effect of judicial independence. It is not very surprising that particularly these domestic institutions play an important role in shaping the incentives of politicians in international politics, as the same institutions have been demonstrated to have important consequences on the national level (Persson and Tabellini 2003; Voigt et al. 2015).

5 Conclusion

The purpose of this analysis was to fill in some gaps in our understanding of general patterns of treaty-making over the last decades. A specific goal of the article was to discover what makes individual democratic states more or less likely to conclude formal international agreements. The theoretical approach taken in this investigation can be summarized as follows. Politicians seek to stay in power and their achievement of this goal depends on choices made within the constraints set by the rules of the political game. We conjecture that this general political economy model of decision-making should aid in discovering under which type of rules politicians are more likely to opt for binding international agreements. The present article developed hypotheses about when treaty-making fits in the electoral calculus of politicians, under the premise that such an electoral calculus crucially depends on the institutional context. We put emphasis on theoretically and empirically exploring the effects of the following rules of the game: electoral systems, power-sharing institutions (veto players), programmatic parties, judicial independence, and constitutional provisions on the competence to initiate, approve, and revoke international treaties.

We offer new empirical evidence that some of these features of political systems influence how frequently states enter into international agreements, even when controlling for a battery of variables that are believed to impact the conclusion of IAs. This is the first time that competing theories of treaty entry are systematically tested against each other. Our analysis simultaneously assesses the effect of several institutional features, enabling us to pinpoint which ones significantly affect treaty entry and which ones do not. In this way we hope to advance the literature on the political economy of treaty accession. We find that, first, majoritarian electoral institutions are associated with lower IA conclusion rates. This indicates that treaties do not fit well into the electoral calculus of politicians who need to please geographically circumscribed constituencies. Our results are in accordance with Rickard (2010) and Phelan (2011), who argue that proportional representation countries resort more often to international law. Second, we provide some evidence that countries conclude fewer treaties when their constitution assigns more actors the competence to revoke such agreements. Third, we find that countries with very low levels of judicial independence conclude more treaties. Finally, programmatic parties and the number of domestic veto players are not associated with the conclusion of treaties.

We now turn to the relevance of our research for the study of international cooperation and make suggestions for future research. First, law and economics scholars and researchers focused on international relations are confronted with the problem of understanding and predicting the behavior of states. This article contributes to an improved understanding of the origins of state behavior. We suggest that state behavior in international politics is to some extent a function of the design of domestic political institutions. At the same time, reform of domestic political institutions might help explain changing foreign policy priorities of states over time.

Second, our results point out the importance of domestic institutions for treaty-making. Future studies could shed light on how the constraining effect of domestic institutions influences the time horizon of governments more generally. Assessing this dimension of state behavior has important implications for international cooperation between governments on issues where defection is the Nash equilibrium. At the same time, future research should test the competing theories of treaty entry in different policy areas and for different types of treaties. While our approach of pooling all types of international agreements and testing our theories on the most general level of international law-making is a useful first step, we expect the underlying heterogeneity to offer highly interesting new insights as well as additional information on the robustness of our results. Finally, our empirical setup allows us only to estimate conditional correlations and although we are confident that these are close to meaningful estimates of a causal effect of exogenous constitutional institutions on political decision-making, we have abstained here from using any causal language. Future research could focus on improving the identification of these causal effects, although this constitutes a serious challenge in comparative political economy (see Acemoglu 2005).

Notes

As of this writing 114 states have ratified the Vienna Convention and 15 more have signed but not yet ratified the convention. Many non-signatory states recognize that the convention or parts of it reflect customary international law.

The dilemma of the strong state is discussed, for example, in Dreher and Voigt (2011). The dilemma involves a commitment problem of the state vis-à-vis its citizens. On the one hand, the state should be strong enough to enforce private property rights. On the other, if a state is powerful enough to enforce property rights, it can misuse its strength to violate those rights. See also Weingast (1995), who argues federalism could be one way of solving the dilemma.

This issue is discussed in Cox and McCubbins (2001).

According to Vreeland (2007) these costs include (1) being denied access to the IMF loan; (2) increased difficulty in rescheduling debt, since informal creditor organizations (such as the Paris Club) require good standing under an IMF agreement; and (3) fear of decreased FDI because of the negative signal from a failed IMF agreement.

This is the case when the executive has an informational advantage and enhanced authority over veto players regarding the conclusion of IAs, which appears to be a plausible assumption. However, research by Mansfield and Milner (2012) on PTAs assumes that domestic veto players have enough political weight to prevent the executive from entering into PTAs. If this applies, governments will be hindered from strategically using IAs to overcome veto player opposition.

For simplicity, we do not show the joint probability or log likelihood function. The interested reader is referred to Cameron and Trivedi (2005: 804) for a comprehensive discussion.

To further rule out problems caused by collinearity in our data, we have checked bivariate correlations between our independent variables as well as variance inflation factors (VIFs) from a model estimated with OLS. All bivariate correlations are below 0.8. Unsurprisingly, the highest positive correlations are between income per capita, democracy, and judicial independence. The highest negative correlations are between income and aid dependence, and between population size and trade openness. The VIFs also suggest no reason for concern about collinearity. Judicial independence and income per capita show the highest VIFs with 5.5 and 4.6 respectively.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2005). Constitutions, politics, and economics: A review essay on Persson and Tabellini’s the economic effects of constitutions. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(4), 1025–1048.

Alcañiz, I. (2012). Democratization and multilateral security. World Politics, 64(2), 306–340.

Baccini, L., & Urpelainen, J. (2014). International institutions and domestic politics: Can preferential trading agreements help leaders promote economic reform? Journal of Politics, 76(1), 195–214.

Barrett, S. (1999). International cooperation and the international commons. Duke Environmental Law and Policy Forum, 10(1), 131–145.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: The database of political institutions. World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Bernauer, T., Kalbhenn, A., Koubi, V., & Spilker, G. (2010). A comparison of international and domestic sources of global governance dynamics. British Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 509–538.

Blume, L., Müller, J., Voigt, S., & Wolf, C. (2009). The economic effects of constitutions: Replicating—and extending-Persson and Tabellini. Public Choice, 139(1), 197–225.

Bormann, N.-C., & Golder, M. (2013). Democratic electoral systems around the world, 1946–2011. Electoral Studies, 32(2), 360–369.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82.

Brennan, G., & Kliemt, H. (1994). Finite Lives and social institutions. Kyklos, 47(4), 551–571.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1–2), 67–101.

Congleton, R. D. (1992). Political institutions and pollution control. Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(3), 412–421.

Copelovitch, M. S., & Ohls, D. (2012). Trade, institutions, and the timing of GATT/WTO accession in post-colonial states. Review of International Organizations, 7(1), 81–107.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (2001). The institutional determinants of economic policy outcomes. In S. Haggard & M. D. McCubbins (Eds.), Presidents, parliaments, and policy (pp. 21–63). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cruz, C., & Keefer, P. (2015). Political parties, clientelism, and bureaucratic reform. Comparative Political Studies, 48(14), 1942–1973.

Dreher, A., Gaston, N., & Matens, P. (2008). Measuring globalization—gauging its consequences. New York: Springer.

Dreher, A., & Lang V. F. (2016). The political economy of international organizations. CESifo working paper 6077.

Dreher, A., & Voigt, S. (2011). Does membership in international organizations increase governments’ credibility? Testing the effects of delegating powers. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39(3), 326–348.

Drezner, D. W. (2003). Introduction. In D. W. Drezner (Ed.), Locating the proper authorities: The interaction of domestic and international institutions (pp. 1–22). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2009). The endurance of national constitutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fang, S., & Owen, E. (2011). International institutions and credible commitment of non-democracies. Review of International Organizations, 6(2), 141–162.

Feld, L. P., & Voigt, S. (2003). Economic growth and judicial independence: Cross-country evidence using a new set of indicators. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(3), 497–527.

Fredriksson, P. G., & Gaston, N. (2000). Ratification of the 1992 climate change convention: What determines legislative delay? Public Choice, 104(3), 345–368.

Funk, P., & Gathmann, C. (2013). How do electoral systems affect fiscal policy? Evidence from cantonal parliaments, 1890–2000. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(5), 1178–1203.

Gagliarducci, S., Nannicini, T., & Naticchioni, P. (2011). Electoral rules and politicians’ behavior: A micro test. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3(3), 144–174.

Ginsburg, T. (2009). International delegation and state disaggregation. Constitutional Political Economy, 20(3–4), 323–340.

Gourevitch, P. A. (1999). The governance problem in international relations. In D. Lake & R. Powell (Eds.), Strategic choice and international relations (pp. 137–164). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Grossman, G. M. (2016). The purpose of trade agreements. In K. Bagwell & R. W. Staiger (Eds.), Handbook of commercial policy (Vol. 1A, pp. 379–434). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84(4), 833–850.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1995). The politics of free-trade agreements. American Economic Review, 85(4), 667–690.

Guzman, A. (2008). How international law works: A rational choice approach. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Hausman, J., Hall, B. H., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the patents-R & D relationship. Econometrica, 52(4), 909–938.

Helfer, L. R. (2005). Exiting treaties. Virginia Law Review, 91(7), 1579–1648.

Henisz, W. J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics and Politics, 12(1), 1–31.

Henisz, W. J. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(2), 355–389.

Heston, A., Summers, R., & Aten, B. (2012). Penn world table version 7.1. Center for international comparisons of production, income and prices. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Hollis, D. B. (2012). Introduction. In D. B. Hollis (Ed.), The Oxford guide to treaties (pp. 1–8). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Imhof, S., Gutmann, J., & Voigt, S. (2016). The economics of green constitutions. Asian Journal of Law and Economics, 7(3), 305–322.

Johns, L., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2009). Dispute settlement, compliance and domestic politics. In J. C. Hartigan (Ed.), Trade disputes and the dispute settlement understanding of the WTO: An interdisciplinary assessment (pp. 139–163). Emerald Group: Bingley.

Keefer, P. (2011). Collective action, political parties, and pro-development public policy. Asian Development Review, 28(1), 94–118.

Keefer, P. (2015). Organizing for prosperity: Collective action, political parties, and the political economy of development. In C. Lancaster & N. van de Walle (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of politics of development. New York: Oxford University Press. (Forthcoming).

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After hegemony: Cooperation and discord in the world political economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kosfeld, M., Okada, A., & Riedl, A. (2009). Institution formation in public goods games. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1335–1355.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 15(1), 222–279.

Linzer, D. A., & Staton, J. K. (2015). A global measure of judicial independence, 1948–2012. Journal of Law and Courts, 3(2), 223–256.

Lizzeri, A., & Persico, N. (2001). The provision of public goods under alternative electoral incentives. American Economic Review, 91(1), 225–239.

Maggi, G., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (1998). The value of trade agreements in the presence of political pressures. Journal of Political Economy, 106(3), 574–601.

Mansfield, E. D., & Milner, H. V. (2012). Votes, vetoes, and the political economy of international trade agreements. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mansfield, E. D., Milner, H. V., & Rosendorff, B. P. (2002). Why democracies cooperate more: Electoral control and international trade agreements. International Organization, 56(3), 477–513.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2014). Polity IV project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2013. User’s manual. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html. Accessed 1 Dec 2014.

Milesi-Ferretti, G. M., Perotti, R., & Rostagno, M. (2002). Electoral systems and public spending. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2), 609–657.

Milewicz, K. M., & Elsig, M. (2014). The hidden world of multilateralism: Treaty commitments of newly democratized states in Europe. International Studies Quarterly, 58(2), 322–335.

Milner, H. V. (1997). Interests, institutions, and information: Domestic politics and international relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Milner, H. V., Rosendorff, B. P., & Mansfield, E. D. (2004). International trade and domestic politics: The domestic sources of international agreements and institutions. In E. Benvenisti & M. Hirsch (Eds.), The impact of international law on international cooperation (pp. 216–243). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moe, T. M. (1990). Political institutions: The neglected side of the story. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 6, 213–253.

Moravcsik, A. (2000). The origins of human rights regimes: Democratic delegation in Postwar Europe. International Organization, 54(2), 217–252.

Mulligan, C. B., & Shleifer, A. (2005). The extent of the market and the supply of regulation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(4), 1445–1473.

Murdoch, J. C., & Sandler, T. (1997). The voluntary provision of a pure public good: The case of reduced CFC emissions and the montreal protocol. Journal of Public Economics, 63(3), 331–349.

Murdoch, J. C., Sandler, T., & Sargent, K. (1997). A tale of two collectives: Sulphur versus nitrogen oxides emission reduction in Europe. Economica, 64(254), 281–301.

Neumayer, E. (2002). Does trade openness promote multilateral environmental cooperation? World Economy, 25(6), 815–832.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutional governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 803–832.

Nzelibe, J. (2011). Strategic globalization: International law as an extension of domestic political conflict. Northwestern University Law Review, 105(2), 635–688.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Padovano, F., Sgarra, G., & Fiorino, N. (2003). Judicial branch, checks and balances and political accountability. Constitutional Political Economy, 14(1), 47–70.

Parisi, F., & Pi, D. (2016). The economic analysis of international treaty law. In E. Kontorovich & F. Parisi (Eds.), Economic analysis of international law (pp. 101–122). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. E. (2000). Political economics: Explaining economic policy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. E. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. E. (2004). Constitutional rules and fiscal policy outcomes. American Economic Review, 94(1), 25–45.

Phelan, W. (2011). Open international markets without exclusion: Encompassing domestic political institutions, international organization, and self-contained regimes. International Theory, 3(2), 286–306.

Putnam, R. D. (1988). Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International Organization, 42(3), 427–460.

Rickard, S. J. (2010). Democratic differences: Electoral institutions and compliance with GATT/WTO agreements. European Journal of International Relations, 16(4), 711–729.

Sandler, T. (2008). Treaties: Strategic considerations. University of Illinois Law Review, 1, 155–180.

Setear, J. K. (1996). An iterative perspective on treaties: A synthesis of international relations theory and international law. Harvard International Law Journal, 37(1), 139–229.

Snidal, D., & Thompson, A. (2003). International commitments and domestic politics: Institutions and actors at two levels. In D. W. Drezner (Ed.), Locating the proper authorities: The interaction of domestic and international institutions (pp. 197–230). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Spilker, G., & Koubi, V. (2016). The Effects of treaty legality and domestic institutional hurdles on environmental treaty ratification. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(2), 223–238.

Sykes, A. O. (2007). International law. In A. M. Polinsky & S. Shavell (Eds.), Handbook of law and economics (Vol. 1, pp. 757–826). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Vaubel, R. (1986). A public choice approach to international organization. Public Choice, 51(1), 39–57.

Voigt, S. (2012). The economics of informal international law: An empirical assessment. In J. Pauwelyn, R. A. Wessel, & J. Wouters (Eds.), Informal international lawmaking (pp. 79–105). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Voigt, S., & Gutmann, J. (2013). Turning cheap talk into economic growth: On the relationship between property rights and judicial independence. Journal of Comparative Economics, 41(1), 66–73.

Voigt, S., Gutmann, J., & Feld, L. P. (2015). Economic growth and judicial independence, a dozen years on: Cross-country evidence using an updated set of indicators. European Journal of Political Economy, 38, 197–211.

Voigt, S., & Salzberger, E. M. (2002). Choosing not to choose: When politicians choose to delegate powers. Kyklos, 55(2), 289–310.

Vreeland, J. R. (2003). The IMF and economic development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Vreeland, J. R. (2007). The international monetary fund: Politics of conditional lending. Abingdon: Routledge.

Weingast, B. R. (1995). The economic role of political institutions: Market-preserving federalism and economic development. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 11(1), 1–31.

World Bank. (2014). World development indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators.

Acknowledgements

Florian Kiesow Cortez gratefully acknowledges funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Helpful comments and suggestions by Christian Bjørnskov, Agnes Brender, Rola El-Kabbani, Dina El-Sayed, Andrew Guzman, Jiwon Lee, Viola Lucas, Nada Maamoun, Stephan Michel, Katharina Pfaff, Konstantinos Pilpilidis, Katharina Pistor, Stefan Voigt, Franziska Weber, and Teresa Wittgenstein are appreciated

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kiesow Cortez, F., Gutmann, J. Domestic institutions and the ratification of international agreements in a panel of democracies. Const Polit Econ 28, 142–166 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-017-9238-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-017-9238-x

Keywords

- Political economy

- Constitutional economics

- International agreements

- Electoral systems

- Power-sharing institutions

- Judicial independence