Abstract

The therapeutic alliance is considered to be one of the most important elements in successful individual therapy and many types of couple, marital, and family therapy. The alliance involves a bond that is developed through investment, mutual agreement, and collaboration on tasks and goals. While substantial evidence exists that the therapeutic alliance plays an important role in multiple aspects of therapy outcomes for individuals, far less empirical attention has been given to the alliance in couple therapy. A primary reason for the dearth of research on alliance within a couples context is the complexity of measuring multiple alliances that interact systemically. The present study sought to examine if a facilitator’s perceived alliance is predictive of the couple’s alliance, and how differences in alliance scores between individuals may impact relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. These questions were examined using data from a brief, two-session intervention for couples, known as the “Relationship Checkup.” Using structural equation modeling, we found that facilitator report of alliance positively predicted both men and women’s report of alliance with the facilitator. Results also indicated that couples who were split on the strength of the alliance had worse outcomes at 1-month follow-up, and split alliance between wives and the facilitator indicated worse outcome for men at 1-month follow-up. Overall, these data suggest that the alliance is an important element for successful brief interventions for couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The therapeutic alliance, also referred to as the working alliance, is regarded as one of the most important elements in successful individual therapy and many types of couple, marital, and family therapy (Friedlander et al., 2018). Alliance has been defined as a “relationship between the therapist system and the patient system that pertains to their capacity to mutually invest in, and collaborate on therapy” (Pinsof & Catherall, 1986, p. 139). There is substantial evidence that the therapeutic alliance plays an important role in multiple aspects of therapy outcomes for individuals and couples (e.g., Friedlander et al., 2011; Horvath et al., 2011). Similarly, partners’ within-system’ alliance, or agreement in alliance, is predictive of outcomes with more split within-system’ alliance predictive of poorer outcomes (see Friedlander et al., 2018). What is less clear is how the agreement between the couple and therapist on the alliance predicts relationship outcomes. The current study was developed to add to this literature by examining the influence of couple and facilitator alliance on couple outcomes following a brief relationship intervention program (Gordon et al., 2019).

Therapeutic Alliance and Couple Therapy

The therapeutic alliance is predictive of outcomes in couple therapy (Anderson et al., 2020; Friedlander et al., 2018; Glebova et al., 2011). A meta-analysis investigated the impact of alliance on mid-treatment improvement, outcomes, and treatment retention in couple and family therapies and found that the associations between alliance and outcomes were moderate, with similar effect sizes to those in individual therapy (Friedlander et al., 2011; Horvath et al., 2011). Although therapeutic alliance is commonly thought to be a necessary factor in couple therapy, the alliance in brief couple relationship education programs has received far less attention. Brief relationship interventions, such as the Marriage Checkup/Relationship Rx,Footnote 1 have documented significant improvements in relationship satisfaction, communication, and intimacy up to 6-months after completing the intervention (Cordova et al., 2014; Gordon et al., 2019). Research examining the alliance in couple relationship education programs have indicated that a positive working alliance is related to a positive change in relationship satisfaction and communication (Ketring et al., 2017; Owen et al., 2011; Quirk et al., 2014). Given the brief nature of the intervention, couples are asked to be vulnerable very quickly during the first time meeting the facilitator. The therapeutic alliance must therefore be built much faster than is required in traditional therapy, so as to facilitate each partner disclosing the vulnerable emotions that are imperative for positive outcomes. Given the brevity of the intervention, it is possible that the alliance has a different impact on relationship outcomes in brief interventions than on longer treatment relationships.

Split Alliance and Outcomes

The agreement on alliance among partners, commonly referred to as within-system’ alliance, is important when considering alliance on treatment outcomes. A limited body of research has examined within-system’ alliance among couples’ ratings of alliance and the effect on outcomes. The results from a previous study conducted by Symonds and Horvath (2004) suggested that alliance was predictive of relationship outcomes only when partners agreed with each other about the strength of the alliance with their therapist. This finding was replicated by Friedlander et al. (2011). Similarly, when couples are split in their alliance with the therapist, the couple may be more likely to terminate treatment (Bartle-Haring et al., 2012). Specifically, Bartle-Haring et al. (2012) found that couples who reported greater differences in alliance by session four were more likely to dropout.

Risk-regulation theory (Murray et al., 2006) may help to explain the importance of agreement about the alliance in that partners’ sense of safety may influence their engagement in couple therapy. Risk-regulation theory seeks to explain how individuals balance the desire to be close to a romantic partner with the risk of experiencing rejection (Murray et al., 2006). When the perception of rejection is high (e.g., if a partner feels that the therapist is “on their partner’s side” and therefore will disagree with him or her) partners may fear rejection and engage in actions to “self-preserve” (e.g., withdraw, retaliate, etc.); however, when the perception of rejection is low (e.g., partners feel equally aligned to therapist and feel that the therapist supports both of them equally), partners may feel safer and act in more vulnerable, relationship-promoting, ways. Therefore, cultivating a positive alliance with both partners appears important, particularly in brief-intervention contexts. Additionally, attachment orientation may also explain the importance of agreement about the alliance wherein individuals with avoidant and anxious attachment orientation may expect their partner and/or their therapist to disappoint them and, in response, they may engage in behavior that may increase the likelihood of their being disappointed or rejected by their partner or therapist (e.g., withdrawing, antagonistic or reactive communication, etc.; Fišerová et al., 2021). Given the mixed findings regarding whether the alliance as rated by therapists or couples predicts outcomes, further investigation is needed to understand these links.

Alliance with Facilitator

Although it is clear that agreement between partners on their alliance with their therapist is predictive of relationship outcomes, less evidence is available on the agreement between the couple and therapist on the alliance and the effect on relationship outcomes. Owen et al. (2011) note this is a limitation of studies examining the role of alliance in couple education programs, and that it is possible that the leaders’ perception of the working alliance could provide further insight into the relational aspects of the alliance. Therefore, it is important to examine the perception of the alliance from the therapists’ and couples’ perspective and whether varying levels of positive alliance affects outcomes in treatment. There is evidence that therapeutic alliance may be perceived differently by clients and therapists in individual therapy (Bedi et al., 2005). For example, results of a meta-analysis examining the association between working alliance and various outcomes of individual therapy demonstrated that the client’s assessment of the alliance is more predictive of treatment outcomes than that of the therapist’s report (Horvath & Bedi, 2002; Horvath & Symonds, 1991). In another meta-analysis on individual treatment, results indicated that client’s views of the alliance remained stable throughout the course of treatment, as compared with those of the therapists that indicated variability over time (Martin et al., 2000).

When examined in couples therapy, research has primarily found that the facilitator’s alliance with the couple has implications on relationship outcomes (Ketring et al., 2017; Owen et al., 2011; Quirk et al., 2014; Symonds & Horvath, 2004). Through the lens of risk-regulation theory, if partners and therapists were split on the strength of the alliance partners may perceive greater risk in being vulnerable and therefore engage in more “self-protective behaviors” rather than vulnerable and relationship-promoting behaviors (Murray et al., 2006). Therefore, we might expect that split alliance between the partners and the therapist would lead to worse outcomes as the couple may not be fully engaged in working on the relationship’s problems. Notably, however, one study found, in a group relationship education program, the facilitator’s perception of group cohesion was not predictive of relationship outcomes (Owen et al., 2011). Thus, further research examining the role of therapist alliance on relationship outcomes is warranted.

Current Study

In sum, research has consistently documented the importance of the partners’ therapeutic alliance on outcomes in couple therapy (Friedlander et al., 2018). What is less clear is how facilitator’s alliance predicts relationship outcomes, as well as how split alliances between each partner and the facilitator predicts relationship outcomes. Split alliance may have implications for the ability to work together, for the couple to trust the therapist, and ultimately on outcomes of therapy or interventions. For example, if the therapist feels that they are aligned with the couple, but the couple does not, the therapist might not have the opportunity to repair this potential problem and the couple’s engagement and/or progress in therapy may be affected. Thus, the current study seeks to add to the literature by examining the association of couple and facilitator alliance on couple outcomes across a brief, relationship education program.

First, we sought to examine whether facilitators’ perceived alliance predicts couples’ perceived alliance. We hypothesized that, facilitators’ perceived alliance will positively predict both partners’ perceived alliance at 1-month follow-up (H1). Next, given that the majority of the studies examining couple alliance and outcomes have examined partner’s data separately, rather than accounting for the interdependence of the data, we sought to employ more systemic analytic procedures to understand the unique contribution of men’s and women’s alliance on relationship using Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling (APIM; Kenny et al., 2006). APIM accounts for the interdependence of the data and thus provides fewer errors and biases in the results. Given the interdependence of the data in the present study, the APIM model is preferable for reducing potential error, particularly Type I errors. Thus, we used an APIM framework to address Hypotheses 2 and 3. Our second aim was to examine whether facilitators’ perceived alliance and each partner’s alliance predicted men and women’s change in satisfaction at 1-month follow-up; we also sought to determine if facilitator’s perceived alliance predicted change in relationship satisfaction above and beyond each partner’s perceived alliance. We hypothesized that split alliance between the facilitator and each partner would negatively predict men and women’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up (H2). Our third and final aim sought to determine whether split alliance between the facilitator and men, and the facilitator and women is predictive of relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up; we also examined whether perception of alliance among partners negatively predicted change in satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. We hypothesized that split between facilitator and men, facilitator and women, and split alliance among partners and will negatively predict change in relationship satisfaction for men and women at 1-month follow-up (H3).

Method

Participants

Couples. A total of 298 cohabitating and/or married heterosexual couples participated in the study. The present sample is a subset of the couples who completed the Relationship Checkup (Gordon et al., 2019; Intervention Total: N = 656). Couples were not eligible to enroll in the intervention if they were under 18 years of age, and if they reported moderate to severe intimate partner violence (e.g., punching with fists, using a knife, hitting with something hard, etc.) in the last 12 months as assessed at the initial screening. The present subset of participants excluded same sex couples due to handling of the interdependent nature of the data. Couples were only included in the present study if their facilitator also participated. Furthermore, this study was begun later in the data collection period, so some couples were not given the necessary measures and thus were excluded from the current study.

Men (M) and women (W) in the current study were primarily between the ages of 25 and 34 (M = 36%, W = 39%) and between the ages of 35 and 44 (M = 26%, W = 26%). Additionally, couples were primarily White (M = 75%, W = 81%) or African American (M = 17%, W = 14%). Additionally, 19% of men and 18% of women identified as Hispanic/Latino. For all demographic variables, those that identified as a racial/ethnic minority (i.e., Hispanic/Latino, African American) were dummy coded as “1”, with remaining individuals that did not identify with those groups dummy coded as “0”. Participants had mostly obtained a high school education or less (M = 47%, W = 43%) or bachelor’s degree (M = 18%, W = 22%). A minority of the population had obtained a vocational degree (M = 11%, W = 12%), associate’s degree (M = 8%, W = 6%), and master’s degree (M = 11%, W = 15%). Couples reported a monthly income below $10,000 (M = 22%, W = 43%), between $10,000 and $19,999 (M = 18%, W = 21%), between $20,000 and $29,000 (M = 17%, W = 13%), and between $30,000 and $39,000 (M = 11%, W = 6%). Most partners were married (66%) or cohabitating (34%), had been involved in a relationship with their current partner for an average of 10 years (SD = 10.20), and had children (63%).

Facilitators

Ten facilitators participated in total. Five facilitators were male and five were female. Most facilitators were 21–29 years old (n = 5), followed by 40–60 years old (n = 3) and then 30–39 years old (n = 2). Facilitators were primarily White (n = 7) and three identified as African American. All facilitators either had a master’s degree in a mental health field or were pursuing a master’s or Ph.D. in a mental health training program (i.e., social work or clinical psychology). Facilitators delivered the intervention to an average of 29.8 couples (SD = 24.65; range = 2–74). Each facilitator was supervised by a Ph.D. level clinical psychologist in a weekly supervision meeting.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Each member of the couple reported their age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, income, and relationship status.

Couple Satisfaction

The 16-item Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI-16; Funk & Rogge, 2007) is a self-report questionnaire that assesses relationship satisfaction. The CSI-16 was completed by both members of the couple at baseline and at the 1-month follow-up. Ratings for all questions are summed; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. The CSI has demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94), and convergent validity with existing measures of relationship satisfaction (Funk & Rogge, 2007). Internal consistency was good at baseline (M: α = 0.96, W: α = 0.97) and at 1-month follow-up (M: α = 0.94, W: α = 0.96). See Table 1 for distribution and internal consistency information and Table 2 for bivariate correlations among study variables.

Couples’ Perceived Alliance

The Therapeutic Alliance Scale (TAS; Córdova, 2007), an unpublished and unvalidated measured created by the study author for the Marriage Checkup, consisting of 15 items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), was used to assess couples’ alliance with the facilitator at the end of the feedback (final) session. Each partner completed the measure, independently of each other at the end of the feedback session. Sample items read, “Our facilitator seemed to understand what is going on in my relationship” and “I felt we were working together with our facilitator in a joint effort.” Internal consistency for the couples perceived alliance was good (M: α = 0.93, W: α = 0.92). Importantly, psychometric data examining the external validity of this measure are not yet established. See Table 1 for distribution and internal consistency information and Table 2 for bivariate correlations among study variables.

Facilitators’ Perceived Alliance

Facilitators completed the Facilitator Assessment Survey (FAS, Córdova, 2007), an unpublished and unvalidated measured created by the study author for the Marriage Checkup consisting of 19-items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), to assess his or her perspective of the therapeutic alliance with the couple on several dimensions. Facilitators completed this measure after the feedback (final) session. Questions assess the facilitator’s perceived effectiveness at delivering the intervention, the bond they felt with the couple, the sense of agreement and collaboration with the couple, and their prediction of the outcome of the couple. Sample items include, “I felt I was working collaboratively with the couple in a joint effort,” “I formed a good working relationship with this couple,” and “I felt the couple was confident in my abilities and judgments.” Internal consistency for the facilitator perceived alliance was good (α = 0.97). Again, it is important to note that psychometric data examining the external validity of this measure are not yet established. See Table 1 for distribution and internal consistency information and Table 2 for bivariate correlations among study variables.

Procedures

Couples

Couples were recruited to take part in a larger study, Relationship Checkup (see Gordon et al., 2019). Recruitment efforts included flyers, community partners, community events, social media presence, and friend/family referrals. Recruitment materials asked if individuals were in committed relationships and advertised a brief checkup to help couples improve their relationships. If eligible to participate, informed consent was provided to each member of the dyad, and couples were mailed the Baseline questionnaires. The intervention consisted of two sessions, a therapeutic assessment and feedback session, each lasting approximately 1.5 h delivered to the couple in a setting of their choice to improve access to care (e.g., their home, integrative care setting). Informed from Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT; Jacobson & Christensen, 1996) and Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002), the therapeutic assessment reviews the couple’s relationship history and identifies relationship strengths and areas of concern. Through empathic joining and brief skills training, the facilitator and couple strive to cultivate compassionate understanding and acceptance between the partners to foster greater intimacy and relationship functioning. At the end of the feedback (final) session, each partner completed a questionnaire that assessed their perceived alliance with the facilitator. At 1-month follow-up, couples were mailed follow-up measures and received gift cards once completed.

Facilitators

All facilitators of the Relationship Checkup were invited to participate in the study and told that the project’s purpose was to examine the interaction of facilitator and client factors and how these may affect couple outcomes. A research assistant met with each facilitator to go over the informed consent and enroll willing facilitators. They were informed that their information would be kept confidential from the PI, including study scores and couples’ outcomes. Facilitators were informed of potential risks and benefits of participating in the study, and that they could choose to withdraw from the study at any point. Facilitators were trained via an intensive 2-day training and annual follow-up trainings. In addition to these formalized training, facilitators observed senior facilitators deliver the intervention and received the treatment manual to study the material. Facilitators also delivered a series of practice interventions to both “mock” and real volunteer couples. These deliveries were reviewed by the PI and/or senior facilitator. If practice interventions were successful, the facilitator began delivering to study couples. Video or audio recording of intervention couples were done for continued supervision purposes. Facilitators completed their measures after the feedback session with the couple and returned them in sealed envelopes. All study procedures were approved by the IRB.

Data-Analytic Strategy

To evaluate model fit, we examined the following goodness-of-fit indices: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). We investigated multiple indices of fit to determine whether the proposed models fit the data. Model fit is considered acceptable following these fit indices’ cut-off values: a RMSEA value smaller than 0.08 and CFI and TLI values > 0.90, and SRMR < 0.08 (Hooper et al., 2008). Items for each measured construct were first parceled into three composites (in order to achieve an identified model) using an Item-to-Construct Balance approach (see Little et al., 2002, 2007 for a review on parceling approaches and benefits). Thus, latent constructs are indicated by the three composite scores corresponding to their respective measured construct.

Prior to running the full SEM model, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to establish that the measurement model was accurately represented by the hypothesized latent constructs. To account for missing data, full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used, which uses all of the available information in the dataset to calculate parameter estimates without excluding cases with missing values (Kline, 2011).

To account for non-independence due to repeated measures, we controlled for baseline levels of relationship satisfaction. Secondly, to control for non-independence of the data due to partners nested within couples, we correlated the error terms associated with partner measures. Finally, we used the “complex” model type statement in Mplus to account for non-independence of couples being nested within facilitators.

After determining that each measurement model fit the data adequately, we examined the associations among the predicted hypotheses. To examine hypothesis 1, we regressed each partner’s perceived alliance, measured as manifest (observed) variable, onto facilitators’ perceived alliance score, measured as a latent construct. The second and third aim of the study was to examine the effect of split alliance on outcomes. To examine hypotheses 2 and 3, we used Actor Partner Interdependence Modeling (APIM; Kenny et al., 2006), which accounts for the interdependence of the data and provides less errors and biases in the results. Given the interdependence of the data in the present study, the APIM model is preferable for reducing potential error, particularly Type I errors. Thus, for hypothesis 2, APIM was used to examine whether a split alliance between facilitators’ and men, and facilitators’ and women, negatively predicted change in relationship satisfaction at follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction.

The split alliance variable was created by determining whether the facilitator and each partner’s perceived alliance differed based on a quartile split dummy code. These quartiles were determined by subtracting Women’s data from Men’s data (M − F), (2) Men’s data from Therapist’s data (T − M), and (3) Females from Therapists’ data (T − F). Calculated scores less than or equal to the 25th quartile and the 75th quartile and above were coded as split alliance (1 = high split alliance) and scores between 25 and 75th (the middle 50%) were coded as agreement on the alliance (0 = none to moderate split alliance). We chose to use the 25th percentile and lowers, and the 75th percentile and higher to represent the more pronounced forms of “split alliance.”

This allowed us to better determine true qualitative differences amongst partners rather than capturing potentially more arbitrary differences when couples scores are not very far apart. Further, in order to examine hypothesis 3, we created a within couple split alliance variable (using the same quartile method described above). Then, relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up was regressed onto split alliance to examine whether split alliance negatively predicted relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Statistical significance was determined at an alpha level of 0.05 or below.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Chi-square and independent samples t tests were conducted to examine whether there were any significant differences between the general sample and the current study sample. The current study sample significantly differed from the general sample on income [t(643) = − 2.95, p < 0.01], marital status [χ2(1, N = 694) = 6.96, p < 0.01], and children [χ(1, N = 694) = 4.82, p < 0.05]. The present study’s sample did not significantly differ from the general sample on race, ethnicity, age, or level of education of the couples, satisfaction at baseline and 1-month follow-up, and partner’s alliance. Income, marital status, and children were initially included as controls in all of the models. To retain the most parsimonious model, control variables that did not predict the outcome variables removed from the final models. Details of which controls were included are described when examining each model below.

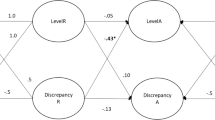

Predictors of Partners’ Alliance

To evaluate the hypothesis that facilitators’ perceived alliance would predict both men and women’s perceived alliance, we ran a regression analysis using SEM. Income and women’s education were controlled for as they were predictive of women’s alliance. The final model fit the data well [χ2 (36) = 0.93, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, and SRMR = 0.05]. The following parameter estimates reported are unstandardized. In support of study hypothesis, results indicated that facilitator perceived alliance positively predicted both men’s and women’s perceived alliance [M: B(SE): 0.33(0.11), p < 0.01; W: B(SE): 0.30(0.08), p < 0.01], though it only explained a small portion of the variance in the outcome variable (R2 = 0.11 and R2 = 0.09 for men and women respectively).

Effect of Facilitator and Partners’ Alliance on Outcome

Next, we examined whether facilitators’ alliance and each partner’s alliance predicted each partner’s change in satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. (H2). We regressed each partner’s manifest relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up onto facilitator perceived alliance, and each partner’s perceived alliance, measured as latent variables, while controlling for relationship satisfaction at baseline. Identifying as Hispanic and education were controlled in the male model and income and identifying as Hispanic were controlled in the female model as they were predictive of outcomes. Those that identified as Hispanic/Latino were dummy coded as “1”, with remaining individuals that did not identify as Hispanic were dummy coded as “0”. The final model fit the data well [χ2 (143) = 1.00, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, and SRMR = 0.03]. In support of study hypothesis, results indicated that the facilitator report of alliance positively predicted men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Facilitator reported alliance, however, did not predict women’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Women’s alliance evidenced significant actor and partner effects. Specifically, women’s alliance positively predicted men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction, as well as her own satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Contrary to expectation, men’s alliance did not evidence significant actor or partner effects. Specifically, men’s alliance did not predict women’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction, or their own satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. All three reports of alliance accounted for 33% (R2 = 0.33) of the variance in men’s relationship satisfaction and 37% (R2 = 0.37) of the variance women’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction. Additionally, men identifying as Hispanic/Latino negatively predicted men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up; similarly, women identifying as Hispanic/Latino negatively predicted women’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction. Full model results are presented in Table 3.

Further, we examined whether facilitator perceived alliance predicted relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction, above and beyond each partner’s perceived alliance. Several Wald chi-square differences tests were conducted to compare two paths at a time. Results indicated that facilitator alliance was in fact predictive of men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up above and beyond men’s alliance [Wald χ2 (1) = 4.17, p < 0.05], but women’s alliance was not predictive of men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up above and beyond facilitator alliance, while controlling for baseline satisfaction [Wald χ2 (1) = 0.03, df = 1, p = 0.86]. Additionally, facilitator alliance was not predictive of women’s satisfaction at the 1-month follow-up above and beyond women’s alliance [Wald χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = 0.95] nor was facilitator alliance predictive of women’s satisfaction at follow-up, above and beyond men’s alliance [Wald χ2 (1) = 0.96, p = 0.33].

Contribution of Split Alliance on Outcome

Lastly, we tested whether a split alliance between the facilitator and men, and the facilitator and women negatively predicted relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction. Men and women identifying as Hispanic/Latino and men’s education were included in the final model as these emerged as significant predictors of relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up when controlling for baseline satisfaction. The final model fit the data well [χ2 (45) = 1.14, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, and SRMR = 0.02]. Results indicated that split alliance between facilitator and men did not have significant actor or partner effects. However, split alliance between women and the facilitator indicated significant partner effects. Specifically, split alliance for women negatively predicted men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up when controlling for baseline satisfaction. However, there were no actor effects for women’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Split alliance accounted for 8% (R2 = 0.08) of the variance in men’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up and 5% (R2 = 0.05) of the variance in women’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Men’s education level, as well as men who were Hispanic/Latino, negatively predicted men’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up when controlling for baseline satisfaction. Women identifying as Hispanic/Latino also negatively predicted their own satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Full model results are presented in Table 4.

Finally, we examined whether split perception of alliance among partners negatively predicted satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction (H3). Men and women identifying as Hispanic/Latino and men’s education were included in the final model as these emerged as significant predictors of relationship satisfaction. The final model fit the data well [χ2 (41) = 1.19, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, and SRMR = 0.02]. As hypothesized, split alliance between partners negatively predicted men’s satisfaction and women’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up, while controlling for baseline satisfaction. Partners’ split alliance accounted for 12% (R2 = 0.12) of the variance in men’s relationship satisfaction and 9% (R2 = 0.09) of the variance in women’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Men who were Hispanic/Latino, negatively predicted their satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Women identifying as Hispanic/Latino also negatively predicted their own satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Full model results are presented in Table 5.

Discussion

The current findings suggests that facilitator perception of the alliance was significantly related to how each partner perceived the alliance. Further, facilitators’ perception of the alliance was predictive of men’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up above and beyond men’s and women’s perception of alliance. Clinically, this finding implies that in a short, two session intervention, facilitators perception of the alliance posses a unique contribution to treatment outcome, at least for men. However, these associations were small, which indicates that there is still significant variability in what the couples experienced and what the facilitators perceived. Facilitators were not specifically trained on assessing the alliance, and there was a wide variation in experience levels in the facilitators (see Gordon et al., 2019 for details), consequently one implication of these findings is that the facilitators of brief intervention might also benefit from more specific training in assessing and building alliances. Further, it is possible that if a facilitator perceives a couple more favorably, he or she may have been more likely to work more effectively in session, show more warmth toward the couple, thus in turn the couple may have felt closer and safer with the facilitator and viewed him or her as more competent, but this hypothesis needs investigation.

Additionally, these findings suggest that split alliance between facilitators and women predicted decreased relationship satisfaction for men at 1-month follow-up, but did not predict women’s own relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up. Further, a split alliance between facilitators and men did not predict men’s relationship satisfaction nor women’s relationship satisfaction. It could be that women’s satisfaction is not impacted by this split alliance possibly because women display higher commitment to work on the relationship and they may also have an “ability to work toward positive outcomes regardless of the relative strength of their relationship with the therapist” (Symonds & Horvath, 2004, p. 453). However, men’s relationship satisfaction suffers when women are not aligned with the facilitator, possibly because a split alliance indicates that the facilitator is missing something important about the couple’s relationship functioning. This lack of coherence may hinder the intervention efficacy, and/or increase conflict or unhelpful relationship behaviors outside of therapy that make her partner less satisfied (e.g., arguing about the treatment, hostility, etc.).

Additionally, women often operate as the “barometers” of relationship functioning (Floyd & Markman, 1983), their report of the alliance may “set the tone” for the therapy. If the facilitator is not accurately capturing what is happening in the relationship, the facilitator may be working towards different goals and not connecting well with the couple if the woman does not feel understood. Therefore, a split alliance between women and the facilitator might result in the intervention not working as well, and thus lead to decreased relationship satisfaction for men. Additionally, it is important to note that the present study did not examine the directionality of the split alliance among each partner and the facilitator; therefore, it is unable to determine the effect of whether women report a stronger alliance than the facilitator, or vice versa. Further elucidating the nature of the split would provide a clearer picture of how exactly a split alliance is predictive of outcomes.

When considered in the context of risk-regulation or attachment theory, a split alliance with a facilitator may be perceived by the lesser aligned partner as a potential risk for rejection, the less aligned partner may act in ways to self-preserve (e.g., withdraw) but are not fruitful for the treatment and/or the relationship in general. According to the present study, it may be particularly important to pay attention to split alliances that form where the female partner (in heterosexual couples) is less aligned with the facilitator as this seems to have implications for her partner’s relationship satisfaction 1-month later, but not her own. The current study extends this finding by identifying how split alliance between partners’ and the facilitators’ predicts outcome for each partner, and again suggests that training facilitators to detect split alliances might be useful.

Contrary to our results, research has largely identified men’s alliance as most predictive of couple therapy outcomes (Anker et al., 2010; Bartle-Haring et al., 2012; Friedlander et al., 2018). Yet, the present study identified women’s alliance to be the salient predictor of treatment outcomes, and it was only significant for her partner’s relationship satisfaction at the 1-month follow-up. However, previous research has also documented that men’s, but not women’s, split alliance with facilitator is predictive of dropout from couple therapy (Bartle-Haring et al., 2012). Thus, it may be the case that men’s alliance may be more important for remaining invested in the treatment (Bartle-Haring et al., 2012), whereas women’s alliance with the facilitator may be more pertinent to her partner’s relationship satisfaction outcomes.

Lastly, split alliance between partners negatively predicted both men’s and women’s relationship satisfaction at 1-month follow-up while controlling for baseline satisfaction. This is consistent with previous research that has documented that split-alliance is associated with poorer outcomes in couple therapy (Friedlander et al., 2018). Additionally, previous research has indicated that alliance was predictive of couple therapy outcome only when partners agreed with each other about the strength of the alliance with their therapist (Friedlander et al., 2011; Symonds & Horvath, 2004). The present study adds to the extant literature by identifying that split alliance with the facilitator negatively predicts relationship satisfaction for both men and women. Whereas women’s alliance and men’s alliance did not impact their own or their partner’s satisfaction at 1-month follow-up equally, split alliance appears to impact both partners in the relationship. A split alliance between partners may predict both partner’s relationship satisfaction because a sense of safety may not be present for both couple members while attempting to work on relationship conflict. If partners do not feel secure in exploring the problems in the relationship, each partner’s relationship satisfaction would likely suffer. Additionally, split alliance may indicate that each partner has different notions about the safety of the relationship, which may lead them to hold back and not fully engage in the intervention because there is too much perceived risk (Murray et al., 2006). Therefore, split alliance could be detrimental to couple outcomes. Again, the present study did not examine the directionality of the split alliance among each partner, such that we are unable to determine the effect of whether women report a stronger alliance than men, or vice versa, on outcomes; further examination of these associations is necessary.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the present study offers a number of strengths, there are several limitations worth noting. Given that the study examined gender effects, the sample was limited to only heterosexual couples future research is needed to determine the effect of alliance on outcomes in same sex couples. Second, the measures used to assess alliance in the present study, the TAS (Córdova, 2007) and the FAS (Córdova, 2007), were author-constructed specifically for the purpose of measuring alliance in Marriage Checkup and psychometric properties examining the external validity of the measure have not yet been established. While neither measure is widely used outside of the context of the Marriage Checkup and the Relationship Checkup, both measures capture the different facets of alliance discussed in the literature: the bond that is developed through investment, mutual agreement, and collaboration on tasks and goals as well as the perception of the therapeutic bond. Future research may consider replicating the findings from the current study with other validated alliance measures.

Additionally, the TAS was also used as a means of assessing the couples’ satisfaction with the intervention and therefore couples completed the TAS at 1-month follow-up (as opposed to directly following the feedback). The facilitators on the other hand, completed the alliance measure following the second/final session. While it has been stated that client’s alliance remains relatively stable over time (Martin et al., 2000), future research may want to examine whether the timing on which the measures were given predicts relationship satisfaction similarly to the present findings. Finally, the facilitator reported on their alliance with the couple as a whole and not with each partner. Therefore, future research may wish to examine differences in the facilitator’s alliance to each partner and how that predicts partner outcomes. Along the same line, an additional limitation is that analysis of split alliance was conducted only in dyadic relations with each partner, and the study did not analyze the split between the facilitator and the couple.

Another limitation worth noting is with regard to the complex model type used to examine the data. The complex model type was used to account for the non-independence of the data. However, 20 groups or clusters have been recommended by Muthén (2018) to use both the complex model type, as well as for multilevel modeling in general. The present study had 13 groups or clusters of facilitators which was below the recommended number of groups. Thus, we suggest that these statistics should be interpreted with caution because the study did not reach the threshold of 20 facilitators as recommended by Muthén and Muthén (1998–2012). We strongly urge that this study be replicated before the results are considered robust.

Future research is needed to gain more understanding into the role each partner’s alliance has on satisfaction, and whether each partner’s perception of the others alliance impacts outcome. Furthermore, it may be useful to determine the directionality of the split alliance, such as whether wives or husbands were split about the strength of the alliance and whether this impacts relationship satisfaction differently. Finally, further research is needed to replicate findings using a systematic approach to studying alliance in the context of couple’s therapy and interventions, such that each report of alliance is measured at multiple time points using a widely used measure, and that uses sophisticated analytic methods as was done in the present study.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that partners’ and therapist’s alliance in brief couple interventions are important to the outcome of the intervention. Clinically, this suggests that therapists must continue to foster the development of the therapeutic alliance with both partners as the alliance does predict relationship satisfaction following the intervention. Furthermore, differing levels of alliance predicted less relationship satisfaction following the intervention, particularly when the alliance is split between facilitator and women. These findings suggest that multiple alliances are a liability to effective treatments. Thus, having a balanced alliance between partners may be just as important as the strength of the alliance itself.

Notes

The Relationship Checkup was adapted from the Marriage Checkup. The Relationship Checkup sought to deliver the program to cohabitating and married couples in the community and oversampled low-income couples.

References

Anderson, S. R., Banford Witting, A., Tambling, R. R., Ketring, S. A., & Johnson, L. N. (2020). Pressure to attend therapy, dyadic adjustment, and adverse childhood experiences: Direct and indirect effects on the therapeutic alliance in couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 46(2), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12394

Anker, M. G., Owen, J., Duncan, B. L., & Sparks, J. A. (2010). The alliance in couple therapy: Partner influence, early change, and alliance patterns in a naturalistic sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(5), 635–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020051

Bartle-Haring, S., Glebova, T., Gangamma, R., Grafsky, E., & Delaney, R. O. (2012). Alliance and termination status in couple therapy: A comparison of methods for assessing discrepancies. Psychotherapy Research, 22(5), 502–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.676985

Bedi, R. P., Davis, M. D., & Williams, M. (2005). Critical incidents in the formation of the therapeutic alliance from the client’s perspective. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 42(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.42.3.311

Cordova, J. V. (2007). The marriage checkup practitioner’s guide: Promoting lifelong relationship health (1st ed.). American Psychological Association.

Cordova, J. V., Fleming, C. J., Morrill, M. I., Hawrilenko, M., Sollenberger, J. W., Harp, A. G., ... & Wachs, K. (2014). The marriage checkup: a randomized controlled trial of annual relationship health checkups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(4), 592–604.

Fišerová, A., Fiala, V., Fayette, D., & Lindová, J. (2021). The self-fulfilling prophecy of insecurity: Mediation effects of conflict communication styles on the association between adult attachment and relationship adjustment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(4), 1279–1302.

Floyd, F. J., & Markman, H. J. (1983). Observational biases in spouse observation: Toward a cognitive/behavioral model of marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 450–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.450

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Heatherington, L., & Diamond, G. M. (2011). Alliance in couple and family therapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022060

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Welmers-van de Poll, M. J., & Heatherington, L. (2018). Meta-analysis of the alliance-outcome relation in couple and family therapy. Psychotherapy (chicago, Ill), 55(4), 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000161

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the couples satisfaction index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572

Glebova, T., Bartle-Haring, S., Gangamma, R., Knerr, M., Ostrom Delaney, R., Meyer, K., McDowell, T., Adkins, K., & Grafsky, E. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and progress in couple therapy: Multiple perspectives. Journal of Family Therapy, 33, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00503.x

Gordon, K. C., Cordova, J. V., Roberson, P. N. E., Miller, M., Gray, T., Lenger, K. A., Hawrilenko, M., & Martin, K. (2019). An implementation study of relationship checkups as home visitations for low-income at-risk couples. Family Process, 58(1), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12396

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6, 53–60.

Horvath, A. O., & Bedi, R. P. (2002). The alliance. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. Oxford University Press.

Horvath, A. O., Re, A. C. D., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness (pp. 25–69). Oxford University Press.

Horvath, A. O., & Symonds, B. D. (1991). Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.38.2.139

Jacobson, N. S., & Christensen, A. (1996). Integrative couple therapy: Promoting acceptance and change. WW Norton & Co.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. The Guilford Press.

Ketring, S. A., Bradford, A. B., Davis, S. Y., Adler-Baeder, F., McGill, J., & Smith, T. A. (2017). The role of the facilitator in couple relationship education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(3), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12223

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Little, T. D., Preacher, K. J., Selig, J. P., & Card, N. A. (2007). New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(4), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407077757

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Collins, N. L. (2006). Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 641–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641

Muthen, B. O. (2018). Multilevel data/complex sample; example for type = complex. Mplus discussion. Retrieved March 16, 2018, from http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/12/776.html?1521596797

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Owen, J. J., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2011). The role of leaders’ working alliance in premarital education. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022084

Pinsof, W., & Catherall, D. (1986). The integrative psychotherapy alliance: Family, couple and individual therapy scales. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 12, 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1986.tb01631.x

Quirk, K., Owen, J., Inch, L. J., France, T., & Bergen, C. (2014). The alliance in relationship education programs. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12019

Symonds, D., & Horvath, A. O. (2004). Optimizing the alliance in couples therapy. Family Process, 43, 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.00033.x

Funding

The current study was funded by the Administration for Children and Families, Grant No. #90FM0022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jessica Hughes is now in private practice in San Diego, CA.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hughes, J.A., Gordon, K.C., Lenger, K.A. et al. Examining the Role of Therapeutic Alliance and Split Alliance on Couples’ Relationship Satisfaction Following a Brief Couple Intervention. Contemp Fam Ther 43, 359–369 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09609-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09609-2