Abstract

Premature termination is significantly understudied in couple and family therapy research yet is a prevalent issue for therapists and has a significant impact on therapeutic outcomes. While therapeutic alliance has been consistently linked to premature termination and other treatment outcomes, little is known about other factors, particularly couple factors, that may influence premature termination in couple therapy. Utilizing dyadic data combined from two different samples of couples seeking therapy, this study examines the influence of relationship satisfaction and therapeutic alliance on premature termination using an Actor Partner Independence Model. Additionally, a chi-square difference test was used to determine differences in therapeutic outcomes among termination-status type groups. Results showed that alliance was not predictive of termination status. Couple factors, particularly relationship satisfaction, were found to be associated with premature termination. That is, couples with lower relationship satisfaction were more likely to terminate therapy prematurely without agreement with their therapist. Findings suggest that couple influences showed stronger associations to premature termination than did therapeutic alliance alone. This highlights a need for therapists to assess how initial relationship satisfaction influences alliance and how each partner’s satisfaction and alliance influence that of the other partner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Marriage and family therapists experience premature termination frequently in their work and know little about its causes. Indeed, research has shown that premature termination is prevalent, with 47% of individual therapy cases terminating prematurely and similar rates among couples and families (Ogrodniczuk et al., 2005). Given premature termination has been associated with a host of deleterious outcomes, understanding premature termination within the context of couple and family therapy could help therapists identify markers of potential termination, and intervene before clients terminate, thus improving the likelihood of sustained gains. Part of the issue, however, of addressing premature termination is the lack of a unified definition across disciplines. There remains debate about how to define premature termination (Swift et al., 2018). In randomized controlled trials drop-out or premature termination is defined as not completing the treatment protocol. Others have defined it as when a patient decides to discontinue treatment before reaching a sufficient reduction in symptoms that led the person to treatment (Leichsenring et al., 2019). For this study, we define termination status based on therapist’s perspective of the clients’ reasons for leaving. Clients either leave with agreement with the therapist that therapeutic goals were reached, clients leave without agreement that the goals have been reached, or clients do not attend a scheduled session and cannot be reached for further sessions. We then use number of sessions attended to further distinguish between the groups based on previous literature (i.e., Xiao et al., 2017).

Despite the prevalence of premature termination in couple therapy (e.g., estimates of 40 to 60%; D’Aniello et al., 2021) and its negative associations with client outcomes, understanding predictors of premature termination and how these variables may interact within the couple is lacking. Furthermore, scholars are still working to understand how one’s partner may influence a client’s decision to terminate prematurely. Accounting for multiple perspectives via partner influence could render a more comprehensive and systemic explanation for premature termination within couple and family therapy. Thus, it is necessary for marriage and family therapists to better understand risk factors for premature termination in order to help mitigate risk of premature termination in couple and family therapy As such, the primary goals of our study are threefold: (1) explore how initial levels of satisfaction and alliance influence alliance at session 2, examining both actor and partner effects and (2) to explore differences in the paths of this model for couple who terminate with agreement, terminate without agreement at or before session 3 and couples who terminate without agreement after session 3.

Trends in Premature Termination

Previous studies have investigated how client characteristics, therapist characteristics, relational context, alliance, and referral sources influence premature termination in individual therapy (Masi et al., 2003). Although risk factors have been identified, research shows mostly inconsistent findings with little evidence for how they lead to premature termination (Anderson, et al., 2019). Additionally, more information is needed to understand how these risk factors influence premature termination for couples, and if any unique risk factors exist for couples in particular regarding partner effects.

Common risk factors for premature termination among couples include low education levels, disagreement among partners about the presenting problem, low relationship satisfaction, diagnoses of substance use/abuse or psychosis, high individual levels of distress, low socioeconomic status, attending some form of therapy in the past, concurrent therapy experience, and being referred to treatment by another provider (Bartle-Haring et al., 2007; Biesen & Doss, 2013; Bischoff & Sprenkle, 1993; Hamilton et al., 2011; Mondor et al., 2013; Tambling & Johnson, 2008). In heterosexual couples, the importance of the male partner’s therapeutic alliance scores as a predictor of premature termination has been demonstrated (Bartle-Haring et al., 2012; Friedlander et al., 2011; Tambling & Johnson, 2008). However, scant research utilizes dyadic data to examine differences and interactions among partners that may contribute to premature termination in couple therapy. How the risk factors identified interact among the couple members, capturing how couple members influence each other in the therapy process, may shed light on the multifaceted and complex factors that influence the decisions to continue treatment or not.

Therapeutic Alliance and Therapy Process

Many studies have identified alliance as a strong predictor of premature termination (Anderson et al., 2019; Jordan et al., 2017; Kegel & Flückiger, 2015; Sly et al., 2013; Westmacott et al., 2010). Thus, exploring therapeutic alliance to determine its effect on treatment attendance for couples may be pivotal. Three constructs have been identified for describing alliance (Bordin, 1979): bond development, goal agreement, and task assignment among the therapist and client(s). Therapists spend significant time developing an alliance with their clients to cultivate trust, encourage motivation, and engage clients in treatment. Research has found that alliance is the strongest predictor of treatment outcomes, accounting for up to 40% of successful therapeutic outcomes (Baldwin et al., 2007; Hogue et al., 2006).

Alliance in couple therapy is complex, as multiple alliances exist within the therapy room (i.e., each partner individually with the therapist, and the couple as a unit with the therapist) and have the potential to influence one another. Bischoff and Sprenkle (1993) identified therapist and client agreement on the presenting problem to be linked with lower rates of premature termination in couple therapy, highlighting the importance of alliance as a factor in treatment engagement. Additionally, the correlation between alliance and positive therapeutic outcomes in couple therapy is greater when partners agree about the strength of their alliance with the therapist, and when the male partner’s alliance is higher (Horvath & Symonds, 2004). In addition to agreement between partners about the strength of their alliance with the therapist, their therapeutic goals and the value of therapy appear to be important variables in ensuring lower premature termination rates for couples in treatment (Friedlander et al., 2011). This knowledge regarding alliance and its impact on the general therapeutic process highlights a need to better understand how alliance might play a role in influencing premature termination. Our study aims to address this need by examining alliance as a predictor of premature termination in couple therapy.

Partner Effects and Therapy Process

D’Anellio and colleauges (2021) review the literature on more complex variables that influence treatment continuance including goals, expectations and social environment. Mondor et al. (2013) demonstrated that when couples come to treatment to resolve ambivalence about whether to stay together, they are more likely to terminate prematurely. Tremblay et al. (2008) showed that attributions of the partners responsibility for the problems and responsibility for “fixing it” are also predictors of premature termination. Others have shown that when couples begin treatment with higher levels of relationship satisfaction, they are more likely to continue treatment longer than couples with lower initial levels of satisfaction. (D’Anellio et al., 2021). However, further research examining how alliance and relationship satisfaction both contribute to premature termination in the dyad is needed.

Our study seeks to better understand partner effects, above and beyond individual effects, and the influence they have on premature termination. Callaci and colleagues (2020) found disengagement in the romantic relationship, influenced by relationship satisfaction, to differ among male and female partners. That is, disengagement from the relationship in men was related to their own attachment needs, whereas disengagement in women was related to both their own attachment needs as well as the attachment needs of their partner. Other scholars have found interpersonal differentiation (the ability to balance separateness needs and connectedness needs within partnerships) to be positively associated with relationship satisfaction for male partners, as well as each partner’s bond with the therapist to be influential on the other partner’s relationship satisfaction (Bartle-Haring et al., 2019). Taken together, these findings indicate that partners’ levels of relationship satisfaction influence each other as well as the overall effectiveness of therapeutic treatment. Our study aims to examine how relationship satisfaction impacts therapeutic alliance and how both contribute to premature termination for couples in therapy.

Theoretical Framework

Given the ramifications premature termination can have on the family system, general systems theory provides the theoretical framework for this paper. General systems theory (GST) builds on Aristotle’s idea that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” and posits that the interrelation among those parts as well as their relations with their environment comprise the system (Von Bertalanffy, 1972). In the context of couples and families, GST proposes that each member exerts reciprocal influence on one another that continues across time (Cox & Paley, 1997). That is, in the context of the couple system, each member of the couple brings their own unique attributes to the relationship, and these attributes interact to create a unique system with its own patterns, rules, and ultimately, symptoms. In this way, the relationship becomes the client (Smith-Acuna, 2010). Couple systems are imbedded within larger systems, leading to interactions across and within levels (Cox & Paley, 1997). Symptoms within the couple system have the potential to not only impact couple members, but also the larger systems the couple belong to, including their nuclear family and other surrounding communities (Bartle-Haring et al., 2007). Further, when couples attempt to change their system, such as through therapy, these changes can be supported or impeded by the larger systemic factors present in their lives. As such, it is paramount for therapists intervening with couples to address these factors and understand how they may impact treatment outcomes. As such, a GST framework guides our exploration of risk factors for premature termination and the impact it has on therapeutic interventions and outcomes.

Current Study

In this study, premature termination is defined as leaving therapy within the first three sessions without agreement between the clients and the therapist. While there are various definitions of premature termination (see Bischoff & Sprenkle, 1993), we chose to operationalize premature termination as leaving therapy within the first three sessions without agreement because the first three sessions are considered part of the intake and evaluation phases of treatment, before “therapy proper” begins (Richmond, 1992, p. 123). Other authors have demonstrated that those who discontinue therapy prematurely achieve poor outcomes similar to those who do not receive treatment, and this is especially true when discontinuation occurs before session 3 (c.f. Xiao et al., 2017). As such, premature termination during these phases of treatment may be significantly different than termination without agreement during the later phase of treatment.

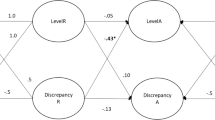

The current study examined premature termination among couples attending therapy with data from their first and second sessions. Dyadic data collected from two samples of couples attending therapy at the university’s on campus training clinic were used. Scant literature has examined the way that couple members influence each other and how this dual influence impacts treatment dropout. Understanding premature termination has significant implications for therapeutic research and practice. By better understanding the risk factors that contribute to premature termination, therapists can assess for and target these behaviors to decrease premature termination and improve treatment outcomes. The current study aims to fill a gap in the literature by exploring both actor and partner effects of relationship satisfaction on alliance development in the first two sessions of treatment and how these associations may vary depending on type of termination. Our research questions are encompassed in the model that can be seen in Fig. 1. In the extended actor partner interdependence model (APIM), initial levels of satisfaction are set to be predictive of initial levels of alliance with the therapist with both actor (male partner satisfaction to male partner alliance) and partner (male partner satisfaction to female partner alliance) effects. Then alliance at session 1 is set to predict alliance at session 2 with both actor (male partner alliance to male partner alliance) and partner (male partner alliance to female partner alliance) effects. These associations will be explored with termination type as a moderator using a group comparison procedure.

Methods

Participants

Sample Study 1

The sample for the first study consisted of 64 heterosexual couples. The average length of the relationships among the couples was 6.59 years (SD = 6.10; range = 1 month to 37 years). Male partners were between 21 and 71 years of age with an average of 32.94 (SD = 10.5). Female partners were between 20 and 71 years of age with an average of 30.98 (SD = 10.28). Twenty-five percent of the sample were cohabiting couples, 8.1% were dating and 53.2% were married. In terms of ethnicity, 68.8% reported being Caucasian, 12.7% African American, 4.7% Hispanic and 2.9% Asian. Over 75% of the sample reported annual incomes of less than $50,000. This data was collected from an on-campus training clinic between 2005 and 2006.

Sample Study 2

The sample from the second study consisted of 56 heterosexual couples. Male partners ranged in age from 19 to 53 with an average of 32.55 (SD = 7.64). Female partners ranged in age from 20 to 53 with an average of 30.23 (SD 7.31). The relationships were between 10 months and 28 years with an average of 6.08 years (SD = 5.63). Twenty-seven percent reported their relationship status as dating, 31% as cohabiting and 42% as married. Eighty-three percent of the male partners were Caucasian with 9.1% African American and 5.5% identifying as multi-racial. Twenty-nine percent reported having a bachelor’s degree, with 20% reporting some college, and 20% reporting a graduate degree. Seventy-eight percent of the female partners were Caucasian, with 12.7% identifying as African American and 4% identifying as multi-racial. Forty-two percent of the female partners reported having a bachelor’s degree, with 21% reporting some college, and 25% reporting a graduate degree. Annual income for the couples ranged from less than $10,000 to over $400,000 with an average of $50,460 (SD = 58,034.44). Fifty percent of the sample had incomes below $36,000 annually. This data was collected from the same on-campus clinic between 2017 and 2020.

Therapists

There were 23 therapists who saw at least one of the clients in the combined datasets. These therapists were all in training in a Ph.D. program for Couple and Family Therapy. Most of the therapists came without a master’s in couple and family therapy, and thus were conducting their first couple therapy sessions. Eight of the therapists came to the program with their master’s degree in Couple and Family Therapy and were accruing hours required by the Ph.D. program. Seven of the therapists were male and the rest were females. The therapists used a variety of approaches including Bowen Family Systems Therapy, symbolic experiential family therapy, narrative approaches, Emotion Focused Couple Therapy, etc. The program takes a more generalist approach, allowing students to select an approach that fits the best for them.

Procedures

Study 1

All clients seeking therapy at the university’s on-campus clinic were informed of the opportunity to participate in a research project, which was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. The clinic operates on a sliding fee scale based on income and number of dependents. The fees during this study ranged from $5 to $60. If the clients consented, they completed an extended intake questionnaire and completed after-session questionnaires following sessions 1 through 6. Only first and second session data is reported in this project. Clients completed the after-session questionnaire and placed them in a locked box upon exiting the clinic. The assigned therapist did not have access to the after-session data. If clients agreed to the research, they received a $10 reduction in their first session fee as an incentive for participation.

Study 2

A similar procedure was followed for the second study, which was also approved by the university’s IRB. All clients seeking therapy at the university’s on-campus clinic were informed of the opportunity to participate in a research project. If they consented, they completed an extended intake questionnaire either online or in paper format and completed after-session questionnaires after sessions 1 through 8. Only data from session 1 and 2 are used for the current study. In this study, clients were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the first condition, they and their therapist shared after-session data graphs beginning at session 3. In the second condition, neither the therapist nor the clients saw their after-session data. Since the randomization procedure did not change procedures in therapy during the first two sessions, it was not controlled for in the analyses. The purpose of the randomization process was to test for the effectiveness of progress monitoring in couple therapy (i.e., Bartle-Haring & VanBergen, 2020). Once session questionnaires were completed online or via paper format, clients who consented to the research received a $20 reduction in their first session fee. The fees during this data collection ranged from $10 or $20 to $180 depending the year the client was seen.

Instruments

Relationship Satisfaction

A single item measure of relationship satisfaction was used for both studies. The item was worded as follows: “On a scale from 1 to 10, how satisfied are you with your relationship.” The scale ranges from 1 (“not at all satisfied”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”). This single item was found to correlate highly with the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (r = 0.86; Glade, 2005). Considering we were assessing relationship satisfaction at each session, a single item measure was appropriate (Fulop et al., 2020). Longer measures of relationship satisfaction would have been more of a burden for the clients, and we were interested in the overall impression of satisfaction in the relationship rather than specific domains of satisfaction.

Therapeutic Alliance

Study 1

We used the Working Alliance Inventory—Shortened Version (WAI-S; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989) which is based on Bordin’s three constructs of alliance—tasks, goals, and bonds (Bordin, 1994). The WAI-S is a 12-item self-report measure that uses a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = never, 7 = always). The WAI-S is made up of three sub-scales: bond, goals, and tasks. An example of an item from the bond subscale (n = 4) is “My therapist and I trust one another.” An example of an item from the goal subscale (n = 4) is “My therapist and I are working toward goals that we both agree on.” Finally, an example of at item from the tasks subscale (n = 4) is “My therapist and I agree about the things I will need to do in therapy to help improve my situation.” The subscale scores can range from 4 to 28 and all three subscale scores can be combined for a total score.

Study 2

We used the Couple Working Alliance Scale (CWAS: Horvath, n.d.; wai.profhorvath.com). This scale has subscales for self in relation to therapist, perception of partner in relation to therapist, and perception of couple as a unit in relation to therapist. Each of these subscales has items that assess the bond with the therapist (i.e. “The therapist and I trust one another”), agreement about tasks and agreement about goals in therapy.

Because these two samples used different instruments for alliance, but the items were similar and were from the same developers we used only the alliance items in reference to self and therapist from study 2. We used an average of the items for bond and an average of the items for goals and tasks combined to form a subscale we called “work.” This combination has been supported in previous literature (c.f. Glebova et al., 2011; Smits et al., 2015). The internal consistency reliability for Study 1 were 0.84 for the work subscale and 0.80 for the bond subscale. For study 2 the bond-self subscale had a Cronbach alpha of 0.86, and the work-self subscale had a Cronbach alpha of 0.87. We chose to combine the bond and work subscale to create a total score for alliance for the current study due to sample size constraints. There were no significant differences in the means of the subscales between the two studies (see Table 1).

It should be noted that although there is evidence that for couples and families in treatment, a shared sense of purpose is part of the alliance (Friedlander et al., 2011), the correlations among the self, partner, and couple subscales of the CWAS were substantial within the individual; the correlation between bond self and bond couple for the male partner was 0.73, and for the female partner was 0.797. The correlations for the work subscale self and couple was 0.77 for male partners and 0.864 for female partners. That is, although a shared sense of purpose is important, it is unclear how partners are distinguishing between their own sense of alliance with the therapist, and how they view the couple’s alliance with the therapist using the CWAS.

Data Analysis

We combined the data from the two different studies. Then we used initial levels of satisfaction to predict initial levels of alliance at the first session, which were set to predict alliance at session 2 with dyad as the unit of analysis using an actor partner interdependence model (APIM: See Fig. 1). We then used a chi-square difference test procedure to determine whether there were differences among the termination status groups. Our goal was to understand what might have gone wrong for couple clients who dropped out of therapy at or before session 3 compared to those who dropped out at later sessions, and those who terminated with agreement. We also examined the number of sessions attended and tested for differences in alliance among the termination status groups. The APIM was performed using Mpus 8.5 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2018).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Group Differences by Termination Status

We created the termination status groups by determining whether the therapist reported that the client terminated with agreement (agreed), whether the therapist reported that the client left without agreement or “no showed” at or before session 3 (drop3), whether the therapist reported that the client left without agreement or “no showed” after session 3 (drop + 3), or if at the end of the study the client continued with treatment or had been referred elsewhere (other). Using these four groups in a MANOVA, we tested for differences among the groups on initial relationship satisfaction and initial alliance scores. The MANOVA was significant (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.765; F = 2.32, p < 0.01). In the tests of between-subjects effects partners’ initial satisfaction scores were significantly different between the groups. In a post-hoc comparison procedure (Scheffe), the couples who left with agreement had higher initial satisfaction scores than all other groups. There were no differences in alliance scores between the groups. The means and standard deviations for the initial satisfaction and initial alliance can be seen in Table 2.

We then performed a doubly repeated ANOVA to understand if alliance at session 1 and alliance at session 2 were different among the groups. We used partner and time as repeated measures. There were no significant main effects or interaction effects. Thus, there appeared to be no differences in the means of alliance at session 1 and session 2 among the termination status groups. Finally, we examined differences in the number of sessions attended among the groups that stayed beyond session 3. The means and standard deviations for number of sessions by termination status can be seen in Table 3. The were no significant differences among the groups.

Results for Model Tests

Our primary research questions are whether or not associations among relationship satisfaction and alliance may have been different among the termination status groups. That is, rather than level of alliance only, we investigated the extent to which partners influenced each other’s alliance, and how this might make a difference in terms of remaining in treatment or dropping out early on. To investigate these research questions, we estimated an APIM (see Fig. 1) that used initial level of satisfaction (which was significantly different among the termination status groups) to predict initial levels of alliance which then predicted alliance at the second session. We assumed that dyads were conceptually distinguishable by gender. In the model, there are actor effects (i.e., partner 1 predictor to partner 1 outcome) and partner effects (i.e., partner 1 predictor to partner 2 outcome). We tested a model that was free to vary among the termination status groups, and then tested models with consecutive equality constraints by using a chi-square difference test to determine which paths could be considered equivalent among the termination status groups. These chi-square difference tests can be seen in Table 4. The fit of the model that allowed all the paths to vary among the groups was good (χ2 (16) = 22.96 p = 0.1148; RMSEA = 0.119; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.86; SRMR = 0.102).

Over the course of the model tests there were three significant differences. The path estimates for the final model can be seen in Table 5. There was a significant difference among the termination status groups for the path from female partners’ initial satisfaction and their alliance; this path was significant and positive for the terminated with agreement group and the “other” group, but not significant for the group that dropped out at or before session 3 or the group that dropped out after session 3. The opposite was the case for the path from male partners’ initial satisfaction and female partners’ alliance at session 1, this path was not significant for the group that terminated with agreement or the “other” group, but was positive and significant for the group that dropped out at or before session 3 and the group that dropped out after session 3. Finally, there was less stability in male partners’ alliance in the group who dropped out after session 3 compared to the other groups.

The final model suggested that male partners’ initial satisfaction was positively associated with their initial level of alliance which was equivalent for all groups. Female partners’ initial satisfaction was positively associated with their initial level of alliance for those who were in the “other” group and those who terminated with agreement. Male partners’ initial satisfaction was associated with female partners’ initial alliance for those in the groups that dropped out. Female partners’ initial satisfaction was not associated with male partners’ initial alliance. There was stability in male partners’ alliance (alliance at session 1 to session 2) (estimate = 0.808) for all but the group who dropped out after session 3 (estimate = 0.392). High stability suggests that there was little change in the alliance scores from session to session for the male partners except for those who dropped out after session 3. The stability estimate for female partners (estimate = 0.476) was significant and equivalent for all groups but lower than that for male partners suggesting that alliance scores changed more for female partners. Male partner’s alliance at session 1 was associated with female partner alliance at session 2 (p = 0.058) for all groups equivalently. Female partner’s alliance at session 1 was not associated with male partner’s alliance at session 2 for any group.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to explore both actor and partner effects of relationship satisfaction on alliance development in the first two sessions of treatment and how these associations varied depending on type of termination. We hoped to fill the gaps in the literature that neglected to consider partner influences on alliance and how these may be associated with termination status. Although there is ample evidence suggesting that alliance is associated with therapeutic outcomes, and some evidence that it is associated with termination, there is little evidence about how couple members influence each other’s alliance scores, and whether that influence might then influence termination. Our study builds on the body of literature by assessing the interactions of relationship satisfaction and alliance at the dyadic level.

Results suggested that couples who terminated with agreement had higher relationship satisfaction than other groups. However, alliance scores did not differ among the termination status groups. That is, rather than alliance, couple satisfaction showed the strongest differences among the termination status groups. These findings are surprising given that alliance has been established as a strong predictor of premature termination across treatment settings and theoretical orientations (Anderson et al., 2019; Jordan et al., 2017; Kegel & Fluckiger, 2015; Sly et al., 2013; Westmacott et al., 2010). However, most of these samples utilized individuals as the unit of analysis rather than couples. As such, when the therapeutic focus is geared towards intervening at the couple level, relational factors (i.e., satisfaction) may have more influence over termination status. Furthermore, premature termination has been associated with a host of negative outcomes for both the therapist, such as job dissatisfaction and financial costs for treatment agencies, and clients, including negative perception of treatment, lack of sustained gains, and delays in needed treatment (Ogrodniczuk et al., 2005; Saatsi et al., 2007; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). As such, it is important for clinicians to gain a better understanding of contributing factors of premature termination at the couple level, as these may differ from individual predictors.

Moreover, just as severity of symptoms have been associated with increased risk of dropout in individual therapy (Eskildsen et al., 2010; Lincoln et al., 2014), dissatisfied couples were more likely to terminate without agreement in our study. The notion that clients would benefit from seeking treatment earlier is pervasive across mental health fields (Haas et al., 2002). Relative to our findings, couples who entered with higher relationship satisfaction successfully completed treatment, whereas more dissatisfied couples did not. These findings suggest that couples with high baseline satisfaction may be seeking therapy to maintain or enhance their relationship, rather than to mitigate threat or repair relational distress. Given relationship maintenance has been associated with relational stability and increased satisfaction and commitment (Ogolsky et al., 2017), these couples may be better motivated to engage in the therapeutic process and reach their goals. Conversely, dissatisfied couples may dropout for an array of reasons: lack of hope and/or lack of perceived progress, incongruence in commitment to therapy and the relationship, and goal discrepancy (Fisher et al., 2018; Jurek et al., 2014; Ward & Wampler, 2010). Therefore, assessing for dyadic variables such as relationship satisfaction early in treatment may be more protective against premature termination than therapeutic alliance.

Study results also yielded novel findings regarding couple member differences in terms of actor and partner effects. Male partners’ relationship satisfaction was positively associated with their initial alliance scores for all termination status groups. Female partners’ baseline satisfaction was positively associated with their initial level of alliance for those in the “other” group and those who terminated with agreement, not the two drop out groups. That is, female partners in couples who stayed in treatment, or who left with agreement, showed an association between their satisfaction and alliance. Additionally, there was a significant association between male partner satisfaction and female partner alliance scores only the groups that dropped out, not in the groups that stayed in treatment or left with agreement. This may suggest that how the female partner views her partner’s satisfaction and her ability to align with the therapist triggers premature termination. It may be the case, that when male partner’s satisfaction is low, female partners have difficulty aligning with the therapist, perhaps feeling blamed about their partner’s lack of satisfaction. However, for male partners, it is important for them to have some level of satisfaction with the relationship in order for them to align with the therapist. There also appeared to be an association between male partner’s initial alliance and female partner’s alliance at the next session that was trending toward significance. Again, this may suggest that female partners are gauging the success of treatment based on their male partner’s response and level of satisfaction with the relationship. This needs to be explored further, especially with couples in which the male partner’s relationship satisfaction is lower than the female’s.

In some ways the findings from this study are consistent with extant literature associating strong alliance and lower symptom severity with greater likelihood for treatment completion (Anderson et al., 2019; Eskildsen et al., 2010; Lincon et al., 2014). However, we have added to the literature by exploring how couple members influence each other and how that may lead to premature termination. Other have found that incongruence in treatment commitment may increase the likelihood of premature termination (Fisher et al., 2018; Halford et al., 2016; Jurek et al., 2014; Ward & Wampler, 2010). Our findings suggest it is perhaps the female partner in these heterosexual couples that may be monitoring this commitment in their male partners and gauging whether or not it makes sense to continue with therapy.

Limitations

Though our study investigated the poorly understood, yet paramount phenomenon of premature termination within the underexplored context of couple relationships, this study is not without its limitations. In terms of partner effects, we only assessed for relationship satisfaction. In addition, our sample largely included White, heterosexual couples. As such, our findings are not generalizable to the larger population and do not capture the unique experiences of minoritized couples. Furthermore, our study did not account for therapist effects (level of training, theoretical orientation, demographics, etc.) and how these factors could have influenced the longevity of treatment. Finally, we used a single item to measure satisfaction. This is justifiable based on study design and has been found to perform in the same way as longer satisfaction measures (Fulop et al., 2020). However, more items or a more nuanced assessment of satisfaction in the relationship could have provided different results.

Future Directions

A noted study limitation is only assessing for relationship satisfaction in terms of actor and partner effects. Though initial levels of satisfaction may well position couples for treatment, assessing the influence of additional dyadic factors (commitment, trust, motivation) will further inform how couple factors may be predictive of premature termination. Additionally, given the majority of relationship research is largely drawn from White, middle-class, heterosexual couples (Helms, 2013), scholar-clinicians must continue our efforts to represent the needs, experiences, and strengths of minoritized populations. In terms of capturing a more holistic picture of the therapeutic experience, there is a growing emphasis on how therapist effects contribute to the therapy outcomes, including retention (Blow & Karam, 2017; Blow et al., 2007; Gurman, 2011). Assessing for therapist-specific factors in future research could provide a more comprehensive picture of contributors leading to premature termination.

Alliance is one of the most consequential elements of the therapeutic experience, and a “common factor” deemed to be essential for creating change in treatment. As such, our findings are surprising given alliance was high for participants and yet did not differ among the termination groups. However, couple factors such as relationship satisfaction were more associated with whether couples continued with treatment. These findings are significant given the emphasis placed on therapeutic alliance and perhaps the lack of attention paid to systemic factors in clinical settings and training programs. As premature termination rates continue to be high, study results indicate that training clinicians to assess for, and respond to, systemic factors (i.e., couple effects) could be beneficial in preventing premature termination.

Our study results indicate that it would also be beneficial for future research to investigate the nuances of the dynamics within couples in terms of power, investment, and willingness to sacrifice, as these factors may underlie a greater likelihood for partners to discontinue treatment when there is incongruence in investment. Furthermore, accounting for times when one partner’s relationship with the therapist is stronger than the other partner’s, or ‘split alliances,’ could also provide insight in how a strong therapeutic foundation might be jeopardized (Escudero et al., 2012; Friedlander et al., 2018). This could be a ripe area for investigation as split alliances have mostly been explored within the context of individual therapy (Safran et al., 2001). Finally, scholar-clinicians are advocating for the consistent use of progress monitoring, or asking clients for feedback about their therapeutic experience, frequently during treatment (Lambert, 2017). Clinicians tend to overestimate positive outcomes relative to observed outcomes and as many as 65% of clients leave treatment without measured benefit (Lambert, 2017). As such, creating a standard routine for clients to report perceptions of progress could allow clinicians to identify challenges more quickly and modify treatment sooner to protect against premature termination.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this study expands on prior work to examine predictors of premature termination. Contrasting with the literature highlighting the importance of therapeutic alliance, we did not find a significant relationship between therapeutic alliance and premature termination. Rather, couple factors, specifically relationship satisfaction, were predictive of premature termination such that lower relationship satisfaction was linked to premature termination. Additionally, results suggest that female partners were more influenced by their male partner’s level of relationship satisfaction and alliance regardless of their own levels of satisfaction and alliance in relation to premature termination. Results highlight the importance of assessing for and addressing relational factors in the initial phases of the therapeutic process to protect against premature termination.

References

Anderson, K. N., Bautista, C. L., & Hope, D. A. (2019). Therapeutic alliance, cultural competence and minority status in premature termination of psychotherapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000342

Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 842–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842

Bartle-Haring, S., Ferriby, M., & Day, R. (2019). Couple differentiation: Mediator or moderator of depressive symptoms and relationship satisfaction? Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(4), 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12326

Bartle-Haring, S., Glebova, T., Gangamma, R., Grafsky, E., & Delaney, R. O. (2012). Alliance and termination status in couple therapy: A comparison of methods for assessing discrepancies. Psychotherapy Research, 22(5), 502–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.676985

Bartle-Haring, S., Glebova, T., & Meyer, K. (2007). Premature termination in marriage and family therapy within a Bowenian perspective. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180600550528

Bartle-Haring, S., & VanBergen, A. (2020). Progress monitoring with couple clients. Psychotherapy Research, 31(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1804640

Biesen, J. N., & Doss, B. D. (2013). Couples’ agreement on presenting problems predicts engagement and outcomes in problem-focused couple therapy. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 658–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033422

Bischoff, R. J., & Sprenkle, D. H. (1993). Dropping out of marriage and family therapy: A critical review of research. Family Process, 32(3), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1993.00353.x

Blow, A. J., & Karam, E. A. (2017). The therapist’s role in effective marriage and family therapy practice: The case for evidence based therapists. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(5), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0768-8

Blow, A. J., Sprenkle, D. H., & Davis, S. D. (2007). Is who delivers the treatment more important than the treatment itself? The role of the therapist in common factors. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(3), 298–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00029.x

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

Bordin, E. S. (1994). Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: New directions. In A. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Wiley series on personality processes. The working alliance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 13–37). Wiley.

Callaci, M., Péloquin, K., Barry, R. A., & Tremblay, N. (2020). A dyadic analysis of attachment insecurities and romantic disengagement among couples seeking relationship therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 46(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12422

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243

D’Aniello, C., Anderson, S. R., & Tambling, R. R. (2021). Psychotherapeutic processes associated with couple therapy discontinuance: An observational analysis using the rapid marital interaction coding system. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12482

Escudero, V., Boogmans, E., Loots, G., & Friedlander, M. L. (2012). Alliance rupture and repair in conjoint family therapy: An exploratory study. Psychotherapy, 49(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026747

Eskildsen, A., Hougaard, E., & Rosenberg, N. K. (2010). Pre-treatment patient variables as predictors of drop-out and treatment outcome in cognitive behavioural therapy for social phobia: A systematic review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), 94–105. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039480903426929

Fischer, M. S., Bhatia, V., Baddeley, J. L., Al-Jabari, R., & Libet, J. (2018). Couple therapy with veterans: Early improvements and predictors of early dropout. Family Process, 57(2), 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12308

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Heatherington, L., & Diamond, G. M. (2011). Alliance in couple and family therapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022060

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Welmers-van de Poll, M. J., & Heatherington, L. (2018). Meta-analysis of the alliance—outcome relation in couple and family therapy. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 356–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000161

Fulop, F., Bothe, B., Gal, E., Cachia, J. K. A., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2020). A two-study validation of a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction: RAS-1. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00727-y

Glade, A. C. (2005). Differentiation, marital satisfaction, and depressive symptoms: An application of Bowen theory. (Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University)

Glebova, T., Bartle-Haring, S., Gangamma, R., Knerr, M., Delaney, R. O., Meyer, K., McDowell, T., Adkins, K., & Grafsky, E. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and progress in couple therapy: Multiple perspectives. Journal of Family Therapy, 33(1), 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00503.x

Gurman, A. S. (2011). Couple therapy research and the practice of couple therapy: Can we talk? Family Process, 50(3), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2011.01360.x

Haas, E., Hill, R. D., Lambert, M. J., & Morrell, B. (2002). Do early responders to psychotherapy maintain treatment gains? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(9), 1157–1172. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10044

Halford, W. K., Pepping, C. A., & Petch, J. (2016). The gap between couple therapy research efficacy and practice effectiveness. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 42(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12120

Hamilton, S., Moore, A. M., Crane, D. R., & Payne, S. H. (2011). Psychotherapy dropouts: Differences by modality, license, and DSM-IV diagnosis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00204.x

Helms, H. M. (2013). Marital relationships in the twenty-first century. Handbook of marriage and the family (pp. 233–254). Springer.

Hogue, A., Dauber, S., Stambaugh, L. F., Cecero, J. J., & Liddle, H. A. (2006). Early therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.121

Horvath, A. O. (n.d.). WAI Home. http://wai.profhorvath.com/.

Jordan, J., McIntosh, V. V., Carter, F. A., Joyce, P. R., Frampton, C. M., Luty, S. E., McKenzie, J. M., Carter, J. D., & Bulik, C. M. (2017). Predictors of premature termination from psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa: Low treatment credibility, early therapy alliance, and self-transcendence. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(8), 979–983. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22726

Jurek, J., Janusz, B., Chwal-Błasińska, M., & De Barbaro, B. (2014). Premature termination in couple therapy as a part of therapeutic process. Cross case analysis. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 16(2), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/26962

Kegel, A. F., & Flückiger, C. (2015). Predicting psychotherapy dropouts: A multilevel approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(5), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1899

Lambert, M. J. (2017). Maximizing psychotherapy outcome beyond evidence-based medicine. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000455170

Leichsenring, F., Sarrar, L., & Steinert, C. (2019). Drop-outs in psychotherapy: A change of perspective. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 32–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20588

Lincoln, T. M., Rief, W., Westermann, S., Ziegler, M., Kesting, M. L., Heibach, E., & Mehl, S. (2014). Who stays, who benefits? Predicting dropout and change in cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 216(2), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.012

Masi, M. V., Miller, R. B., & Olson, M. M. (2003). Differences in dropout rates among individual, couple, and family therapy clients. Contemporary Family Therapy, 25(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022558021512

Mondor, J., Sabourin, S., Wright, J., Poitras-Wright, H., McDuff, P., & Lussier, Y. (2013). Early termination from couple therapy in a naturalistic setting: The role of therapeutic mandates and romantic attachment. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-012-9229-z

Muthen, B., & Muthen, L. (1998–2018). Mplus version 8.2. Statistical software program. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

Ogolsky, B. G., Monk, J. K., Rice, T. M., Theisen, J. C., & Maniotes, C. R. (2017). Relationship maintenance: A review of research on romantic relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(3), 275–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12205

Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Joyce, A. S., & Piper, W. E. (2005). Strategies for reducing patient-initiated premature termination of psychotherapy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 13(2), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10673220590956429

Richmond, R. (1992). Discriminating variables among psychotherapy dropouts from a psychological training clinic. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 23(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.23.2.123

Saatsi, S., Hardy, G. E., & Cahill, J. (2007). Predictors of outcome and completion status in cognitive therapy for depression. Psychotherapy Research, 17(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600779420

Safran, J. D., Muran, J. C., Samstag, L. W., & Stevens, C. (2001). Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.406

Sly, R., Morgan, J. F., Mountford, V. A., & Lacey, J. H. (2013). Predicting premature termination of hospitalized treatment for anorexia nervosa: The roles of therapeutic alliance, motivation, and behavior change. Eating Behaviors, 14(2), 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.007

Smith-Acuna, S. (2010). Systems theory in action: Applications to individual, couple, and family therapy. Wiley.

Smits, D., Luyckx, K., Smits, D., Stinckens, N., & Claes, L. (2015). Structural characteristics and external correlates of the working alliance inventory-short form. Psychological Assessment, 27(2), 545–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000066

Swift, J. K., & Greenberg, R. P. (2012). Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(4), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028226

Swift, J. K., Spencer, J., & Goode, J. (2018). Improving psychotherapy effectiveness by addressing the problem of premature termination: Introduction to a special section. Psychotherapy Research, 28(5), 669–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1439192

Symonds, D., & Horvath, A. O. (2004). Optimizing the alliance in couple therapy. Family Process, 43(4), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.00033.x

Tambling, R. B., & Johnson, L. N. (2008). The relationship between stages of change and outcome in couple therapy. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701290941

Tracey, T. J., & Kokotovic, A. M. (1989). Factor structure of the working alliance inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1(3), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.1.3.207

Tremblay, N., Wright, J., Mamodhoussen, S., McDuff, P., & Sabourin, S. (2008). Refining therapeutic mandates in couple therapy outcome research: A feasibility study. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701236175

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1972). The history and status of general systems theory. Academy of Management Journal, 15(4), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.5465/255139

Ward, D. B., & Wampler, K. S. (2010). Moving up the continuum of hope: Developing a theory of hope and understanding its influence in couples therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36(2), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00173.x

Westmacott, R., Hunsley, J., Best, M., Rumstein-McKean, O., & Schindler, D. (2010). Client and therapist views of contextual factors related to termination from psychotherapy: A comparison between unilateral and mutual terminators. Psychotherapy Research, 20(4), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503301003645796

Xiao, H., Hayes, J. A., Castonguay, L. G., McAleavey, A. A., & Locke, B. D. (2017). Therapist effects and the impacts of therapy nonattendance. Psychotherapy, 54(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000103

Funding

No funds, grants, or other supports were received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by SB-H. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Data from this project is available from the last author.

Code Availability

SPSS and Mplus were used in the data analysis.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All study procedures were approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

All participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the research and fully informed about the nature of the project and what their participation would entail in a separate consent document from their consent to treatment.

Consent for Publication

The PI for the project, Suzanne Bartle-Haring, is an author on this paper and consented to its publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bartle-Haring, S., Walsh, L., Blalock, J. et al. Using Therapeutic Alliance to Predict Treatment Attendance Among Couples. Contemp Fam Ther 43, 370–381 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09602-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09602-9