Abstract

Previous literature has not examined the processes underlying the relations among parent–child relationship quality, parental psychopathology, and child psychopathology in the context of gender. Further, research examining these variables in emerging adulthood is lacking. The current study examined whether parent–child relationship quality would mediate the relation between parental and child psychopathology, and whether gender moderated these associations. Participants were emerging adults (N = 665) who reported on perceptions of their parents’ and their own psychological problems as well as their parent–child relationship quality. Results indicated that the relation between parental internalizing problems and parent–child relationship quality was positive for males, and that mother–child relationship quality was related positively to psychological problems in males. This suggests that sons may grow closer to their parents (particularly their mother) who are exhibiting internalizing problems; in turn, this enmeshed relationship may facilitate transmission of psychopathology. Mediational paths were conditional upon gender, suggesting moderated mediation. Overall, the current study emphasizes that the complexities of parenting must be understood in the context of gender. Further, the mother–son dyad may particularly warrant further attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clear evidence supports that parental psychopathology, as broadly defined by internalizing and externalizing problems, and the quality of the parent–child relationship have a significant influence on child psychological adjustment, both in the short and long term [5, 44]. Specifically, the parent–child relationship has an impact on children’s view of their own self-worth as well as other relationships, and these effects can progress into adulthood [41, 42]. Parental psychopathology is linked to a range of externalizing and internalizing disorders in children, and some research has demonstrated that this effect specifically impacts children as they enter young adulthood [40, 48].

Although research provides clear associations between child outcomes and parent–child relationship quality as well as parent internalizing and externalizing problems, less research has examined the processes among these variables. For example, parental internalizing and externalizing behavior problems likely have a significant effect on the parent–child relationship, and these associations could be affected further by the gender of parents and children. Thus, the current study examined the mediational effect of parent–child relationship quality on the relation between parental and child internalizing and externalizing problems in the context of gender. As this study examines multiple pathways and relations, we examined these two broad psychopathology categories instead of more specific problem domains in order to make results clear and concise.

Parent–Child Relationship Quality

The parent–child relationship holds a significant impact on children in many ways. Attachment theory suggests that individuals develop working models or representations as well as expectancies of what relationships should be based on their prior dyadic experiences (e.g., mother and child, father and child). These experiences guide expectations about future relationships [42]. For example, Allen and Hauser [2] found that maternal behaviors promoting children’s autonomy and relatedness in adolescence predicted attachment security 11 years later. These results suggest that parent–child relationship quality at younger ages is predictive of both romantic relationship processes and negative affect in young adulthood. Moreover, research shows that the more secure young adults currently view their past parent–child relationships, the better quality their current romantic relationship [42].

Parent–child relationship quality has further impact beyond young adulthood relationship quality. Repetti et al. [41] showed that children raised by cold, unsupportive, and neglectful caregivers faced vulnerabilities that had epigenetic and thus long-term health consequences. Specifically, living with parents who were easily irritated, angered by their child, and/or had the tendency to abuse (psychologically or physically) had lasting effects on children’s development including disruptions to emotional processing, social competence, and physiological stress response systems. Repetti et al. [41] suggested that this “risky family” scenario creates a complex integrated bio-behavioral profile, which yields later significant mental and physical health problems, including early mortality. They noted that the emotional, social, and biological processes disrupted by growing up in a cold, neglectful, abusive, and/or unsupportive environment are linked to each other in a cascade type of manner. Conversely, parental warmth and responsiveness is often linked to better interpersonal adjustment, self-regulation abilities, and academic adjustment [5]. Parental negativity and lack of affection may lend to a host of problems for children, including internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Additionally, the type of psychopathology that the children develop may depend on the types of parenting behaviors that impact the parent–child relationship quality in different ways. For example, having an affectionless parent often yields childhood internalizing problems, whereas having a parent that is inconsistent or insufficient in time spent monitoring and caring for the child may lead to externalizing or conduct problems [6]. Conversely, having a parent that is too involved or over-controlling can yield lasting problems with self-regulation and coping, which are key traits related to both internalizing and externalizing symptomology [5, 13].

Further research has shown that negative or conflictual parent–child relationships yield specific types of externalizing problems that often evolve into varying problems in young adulthood. Burt et al. [7] found parent–child conflict shared a moderate relation with ODD, a childhood externalizing disorder, and a small but significant relation with ADHD in males and females. ADHD, also considered an externalizing disorder, often persists into adulthood, causing a number of potential professional and personal development issues [21]. Moreover, childhood ADHD has been linked to adulthood antisocial personality disorder [35]. Of those who met criteria for ODD in childhood, 92.4% will meet criteria for at least one other DSM-IV disorder. Specifically, evidence suggests these children will have a 46% chance of developing a mood disorder, 62% chance of developing an anxiety disorder, 68% chance of developing an impulse-control disorder, and 47% chance of developing a substance use disorder [37]. Though this research refers to specific problems (i.e., ADHD and ODD), these disorders are broadly classified as externalizing problems and are therefore relevant to the outcomes assessed in the current study.

Parental Psychopathology

Parental internalizing and externalizing behaviors have strong impacts on parent–child relationships and can yield similar mental health problems in their children by young adulthood. Further, the type of problems experienced by children (externalizing, internalizing, or both) may vary as a function of the parents’ type of psychopathology. In males, parental depression significantly related to children’s peer problems, and parental substance use significantly predicted young adulthood substance use disorders [40]. Lieb et al. [28] found that children of parents with internalizing problems were more likely to be depressed and experienced more severe depression than offspring of non-affected parents. Their findings also suggest that significant differences do not occur between children who have one parent versus two with psychopathology, although this lack of differentiation may vary as a function of the illness and severity of illness. Specifically, children with two affected parents were more likely than children with one affected parent to have bipolar II disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Further, research shows that parental mental illness is often associated with parental abuse, which can lead to a cascade of problems that endure across children’s lifespan [23, 46].

Not only are children of parents with internalizing and externalizing problems at higher risk for overall development of psychopathology, but they also experience earlier development of symptomology in contrast to children of mentally healthy parents. Specifically, research has found that children of depressed parents are 3 times more likely to have anxiety, major depression, and substance use problems than children of non-depressed parents, suggesting that parent internalizing problems may yield both internalizing and externalizing problems in the youth [48]. Importantly, the same study found that the period that entailed the highest rate of major depression in the offspring of depressed parents ranged between 15 and 20 years. This age range is noteworthy, as it is interestingly a time when adolescents are becoming young adults, often spending decreased time with parents and/or moving away from home, finding their independence from parents [3].

Parental ADHD, considered an externalizing behavior disorder, also has been linked to a broad range of problems both within the offspring and the parent–child relationship. For example, ADHD symptoms in expectant mothers was inversely related to self-efficacy and positive expectations of their child and future role as a mother [36]. Further, parents with ADHD have been shown to be less satisfied with their child, have lower parental self-esteem, and have difficulties carrying out positive and necessary parenting behaviors [4, 47]. Parents with ADHD reported higher levels of ineffective parenting, specifically regarding inconsistent discipline [4]. Overall, research suggests that parents with ADHD, especially comorbid with an internalizing problem like depression, were much more likely to have a child with a range of psychological dysfunction [25].

Parental depression, considered an internalizing behavior problem, has been shown to have significant impacts on parenting behaviors, which directly influence parent–child relationship quality. For example, maternal and paternal major depression has been linked to both parent–child conflict and problematic parenting behaviors and practices, including emotional and physical unavailability, unresponsiveness, self-absorption, and irritability [26, 31]. One meta-analysis showed that parental depression was highly related to coercive and angry parental behaviors, as well as disengagement to a lesser extent [29]. Both paternal and maternal depressive symptoms have negative impacts on the parent–child relationship, but these impacts may differ as a function of parent gender [34]. Depressed mothers may speak less, be slower in responsiveness, and respond more negatively or critically to their children [12]. Fathers’ depressive symptoms are more often associated with reduced positive interactions, such as less warmth and more psychological control [10]. Importantly, evidence suggests that these parenting traits may mediate the relation between parental depression and children’s behavior problems [14]. Though much research has evaluated the effects of maternal and paternal depression on children, less research has focused on the effects of broader internalizing symptomology, which would include other problems like anxiety and anger.

Gender Differences

The gender of both parents and children plays a vital role in understanding the relations among parental psychopathology, parent–child relationship quality, and child adjustment. Evidence suggests that males who have parents with both internalizing and externalizing disorders may be more at risk than females for later externalizing issues, such as antisocial problems and substance use [40]. Additionally, McKinney and Milone [32] found that although maternal and paternal psychopathology shared a strong direct relation with child psychopathology, authoritative parenting behaviors mediated this relationship for mothers but not fathers. Ohannessian et al. [38] found that paternal but not maternal psychopathology was strongly related to adolescent alcohol use, supporting other research finding that paternal psychopathology is linked more to children’s externalizing problems, whereas maternal psychopathology is linked more to children’s internalizing problems [39].

Other research has obtained mixed findings regarding gender. Specifically, Lieb et al. [28] found that among children of fathers with psychopathology, adolescents were more at risk for substance use problems than young adults, whereas children of two affected parents predicted stronger risk for agoraphobia for young adults but not for adolescents. Moreover, Ohannessian et al. [38] did not find any significant interactions based on gender and parent–child psychopathology. These findings contradict developmental theory as well as other research, suggesting that adolescent gender differences do exist when examining the effects of parental psychopathology [19], although it should be noted that Ohannessian et al. [38] suggested their interactions may not have been sufficiently powered.

Although literature pertaining to the effects of parental psychopathology and parent–child relationship quality has supported gender differences in both parents and children, these differences are often inconsistent or unclear [38]. Literature suggests that this could be due to differences in age groups. For example, perhaps adolescents still living at home who are more frequently exposed to their parents are impacted differently by parental internalizing and externalizing problems and their relationship with their parents, in contrast to young adults who may be more physically and/or emotionally distant from their parents [38].

Current Study

Overall, it is clear that parent–child relationship quality and parental psychopathology have lasting impacts on children that extend into young adulthood. Emerging adulthood, ages 18–25 years, is a time of changes, developing relationships, and great uncertainty that corresponds with pressure to become independent [3]. Thus, problems associated with childhood may either come to the surface or become exacerbated during this often stressful phase of life. Although research has demonstrated the impact of parental psychopathology and parent–child relationship quality on children [7, 37, 41], research examining how these variables impact emerging adults is lacking. Moreover, previous literature has found gender differences when examining parent behaviors and childhood outcomes [11]; however, the processes underlying the relations among parent–child relationship quality, parental psychopathology, and child psychopathology have not been examined together within the context of gender.

As discussed above, varying types of parental psychopathology (i.e., specific internalizing and externalizing problems) share strong associations with different child psychopathology outcomes as well as parent–child relationship quality, which also shares its own association with child psychopathology [5]. Further, it is clear that differences in children’s type of psychopathology and the quality of the parent–child relationship may be related to the type of psychopathology experienced by the parent; however, previous research has produced differing results when examining internalizing and externalizing pathology of both children and parents [6, 40, 48], suggesting that these associations are still unclear. Although these individual relations are supported, how parent–child relationship quality may mediate the relationship between parental and child psychopathology also is still unclear [33]. Given that research proposes potential mediators, such as parenting behaviors, and moderators, such as gender [20], the next logical step is to examine the following research question: How does parent–child relationship quality and gender influence the relation between parent and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Specifically, the current study aims to examine how parent–child relationship quality may mediate the relation between maternal and paternal externalizing and internalizing problems and daughter and son externalizing and internalizing problems, and whether gender of both parents and children moderates this association. Below are five hypotheses related to this research question.

As prior literature indicates that various types of parental psychopathology (both externalizing and internalizing) have direct impacts on the relationship with their youth (e.g., [4, 36, 47]), hypothesis 1 stated that parental psychopathology (both internalizing and externalizing problems) will be negatively associated with parent–child relationship quality. As prior research suggests clear associations between parent and child psychopathology (e.g., [25, 28, 32, 40]), hypothesis 2 stated that parental psychopathology (both internalizing and externalizing problems) will be positively associated with emerging adulthood psychopathology.

Prior literature has demonstrated factors that affect the parent–child relationship quality, such as level of affection and time spent caring or monitoring, are linked to externalizing and internalizing related symptomology in the youth [5, 6, 13]. Hypothesis 3 stated that parent–child relationship quality will be negatively associated with emerging adult internalizing and externalizing problems.

Prior evidence indicates clear linkages between parent psychopathology and factors related to the parent–child relationship (e.g., [4, 36, 47]), as well as between the parent–child relationship and youth psychopathology (e.g., [5, 6, 13]). Therefore, hypothesis 4 stated that parent–child relationship quality will mediate the relation between parental internalizing and externalizing problems and emerging internalizing and externalizing problems.

Prior research suggests gender differences in both child and parent when examining the associations between parental psychopathology and child adjustment (e.g., [32, 38, 40]). Hypothesis 5 stated that the mediational effect will be conditional on gender. Based on prior work suggesting that daughters of parents with psychological dysfunction may be more at risk for internalizing problems while males may be more at risk for externalizing problems (e.g., [16]), it was hypothesized that females will demonstrate stronger relations than males in internalizing and maternal pathways. Specifically, females will demonstrate stronger relations between maternal internalizing problems and parent–child relationship quality, and stronger relations between the parent–child relationship quality and emerging adulthood internalizing problems. It also was hypothesized that males will demonstrate stronger relations between paternal externalizing problems and parent child relationship quality. Further, males will show stronger relations between parent–child relationship quality and emerging adulthood externalizing problems.

Method

Participants

The sample included 665 participants (37.3% male, 62.7% female) who ranged in age from 18 to 25 years (M = 18.83, SD = 1.14) and were attending a large Southern university in the United States (90.4% of the sample originated from a Southern state). Participants reported themselves to be Caucasian (73.0%), African American (21.1%), Hispanic (2.1%), Asian (2.0%) or Other (1.8%). Participants reported that 53.7% of fathers and 57.6% of mothers had a 4-year degree or higher. Participants reported that their family structure consisted of both biological parents (69.1%), biological and stepparent (10.4% mother and stepfather, 2.1% father and stepmother), single biological parent (13.7% mother, 2.6% father), or other caregivers (2.1%).

Procedure

Data from participants were aggregated over several studies at a Southern university in the United States. All respondents came from a participant pool in a psychological research program and completed studies online. An informed consent form for the study they participated in was presented first to participants, who then responded to all questionnaires in random order with respect to current perceptions and completed mother and father forms separately (i.e., data are from participants’ current perspective of their parents’ behaviors, their relationship with their parents, and their own behaviors). Participants were given a printable debriefing form and research credit upon completion of or voluntary withdrawal from their study.

Measures

Parent–Child Relationship Quality

The Parental Environment Questionnaire (PEQ; [15]) assessed parent–child relationship quality using subscales including conflict (e.g., my parent often criticizes me), involvement (e.g., my parent does not know how I spend my time), regard for parent (e.g., I am proud of my parent), regard for child (e.g., my parent loves me no matter what I do), and structure (e.g., my parent makes it clear what he/she wants me to do) using a scale ranging from definitely true to definitely false. The PEQ has demonstrated good psychometrics [15] and alphas of the subscales ranged from 0.76 to 0.91 in the current study.

Parent and Child Psychopathology

The Adult Self-Report (ASR) and Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL) are 123-items measures used to measure psychological problems using responses ranging from not true to very true or often true [1]. The ASR is completed as a self-report measure and the ABCL is completed by a rater on a ratee (e.g., emerging adult children on their parents). The current study examined the two externalizing and internalizing broadband scales of the ABCL and ASR. The externalizing scale includes items assessing problems related to various externalizing behaviors, such as aggression and unconventional behaviors (e.g., breaks rules at work or elsewhere, argues a lot) and the internalizing scale includes items pertaining to internalizing behavior problems, such as depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints (e.g., cries a lot, complains of loneliness). The ASR and ABCL have demonstrated good psychometrics [1], and alphas of the subscales ranged from 0.88 to 0.92 in the current study.

Data Analytic Plan

Structural equation modeling was conducted using AMOS 24.0. Observed variables included maternal, paternal, and emerging adult internalizing and externalizing problems as measured by the ABCL and ASR. Latent variables included maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality, which was indicated by the five subscales of the PEQ. Maternal and paternal effects were modeled together to allow for direct comparison of maternal and paternal effects as well as to account for each parent’s shared variance (i.e., to avoid overestimating one parent’s effects). For the purposes of SEM, a sample size of 665 is considered good [27], and a power analysis assuming a small effect with a power of 0.80 indicates a required sample size of 626. The maximum likelihood method of covariance structure analysis was used. First, a measurement model was tested to ensure adequate identification of the maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality constructs as well as to obtain correlations among the variables. Next, a single structural model that included maternal and paternal variables as well as internalizing and externalizing problems was tested and used to examine the hypotheses.

Hypotheses 1 through 3 were examined using direct effects found in the structural model. To test for mediation in hypothesis 4, indirect effects (i.e., the statistical effect of the predictor variable on the predicted variable through the mediator variable) were used, which have been recently suggested by statisticians [30] to better test for mediation. Indirect effects were estimated with bootstrapping using 2000 iterations, which is considered to be more robust than typical tests of indirect effects [22]. To test hypothesis 5, moderation by gender was examined with multiple group analysis using pairwise parameter comparisons, a statistical test comparing the difference between path coefficients [8]. This comparison produces a Z score indicating the statistical difference between groups on a particular path coefficient. Male and female path coefficients were compared to determine relationships moderated by gender.

Results

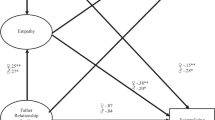

The five subscales of the PEQ were loaded onto a latent construct to indicate maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality using AMOS 24.0. The model fit the data well (CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.03) and factor loadings of the five subscales indicated good convergent validity: structure = 0.70–0.75, regard for child = 0.84–0.85, regard for parent = 0.92 across both parents, involvement = 0.80–0.85, and conflict = − 0.52 to − 0.54. This model was found to be invariant across gender in the current study (i.e., gender groups invariance test: χ2 (10, N = 2362) = 9.92, ns). Table 1 shows correlations among variables in the measurement model. Upon appropriate specification of the measurement model, the structural model as shown in Fig. 1 was tested and fit the data well (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.08).

♂ indicates males, ♀ indicates females. Italicized paths represent effects for emerging adult internalizing problems, bolded paths represent effects for emerging adult externalizing problems. Correlations among exogenous maternal and paternal internalizing and externalizing problems omitted for clarity and shown in Table 1. *p < 0.05

As shown in Fig. 1, maternal and paternal externalizing problems were negatively associated with maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality, respectively, supporting hypothesis 1. Failing to support hypothesis 1, the relations between maternal and paternal internalizing problems and maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality, respectively, were not significant when examining females and were positive when examining males. Supporting hypothesis 2, maternal and paternal internalizing and externalizing were positively associated with male and female internalizing and externalizing in the majority of the possible combinations between mother and father and daughter and son internalizing and externalizing problems. The only exceptions include the non-significant relations between paternal externalizing and male internalizing problems, paternal externalizing and male externalizing problems, and maternal externalizing and female internalizing problems. Hypothesis 3 largely was not supported as only the relations between maternal parent–child relationship quality and male internalizing and externalizing problems were significant.

As shown in Table 2 and supporting hypothesis 4, maternal externalizing problems had a significant indirect effect on male internalizing and externalizing problems. Failing to support hypothesis 4, other indirect effects were not significant. Hypothesis 5 was partially supported, as the meditational paths were conditional upon gender; however, results were unexpected. Only two paths statistically differentiated males from females, and these paths suggested positive relationships among maternal internalizing problems, parent–child relationship quality, and emerging adult internalizing problems in the mother–son relationship only. As shown in Table 2, males significantly differed from females when examining the relationship between maternal internalizing problems and maternal parent–child relationship quality as well as maternal parent–child relationship quality and emerging adult internalizing problems. In both cases, the female path shared a negative association as hypothesized, although these paths were not significant. However, both paths were positive when examining males, suggesting that increased maternal internalizing problems are associated with better mother–child relationship quality, which is associated with increased male internalizing problems. Given that males and females significantly differed when examining the path between maternal parent–child relationship quality and emerging adult internalizing problems and that this indirect effect of maternal externalizing problems on emerging adult internalizing problems through maternal parent–child relationship quality is significant for males but not females, moderated mediation is suggested for this path only.

Other notable results include differences between parental externalizing and internalizing problems in the context of the parent–child relationship. Specifically, parental internalizing problems shared small or non-significant relations with parent–child relationship quality (bs ranging from 0.04 to 0.17), whereas parental externalizing problems shared large negative associations with parent–child relationship quality (bs ranging from 0.62 to 0.78).

Discussion

Hypothesis 1 predicted that parental psychopathology will be negatively associated with parent–child relationship quality. Partial support for this hypothesis was demonstrated. Though results show that maternal and paternal externalizing problems were negatively associated with maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality as expected, results differ in regard to paternal and maternal internalizing problems. The relations between maternal and paternal internalizing problems and maternal and paternal parent–child relationship quality was not significant for females but was negative as hypothesized. Conversely, the relations between maternal and paternal internalizing problems and parent–child relationship quality was positive for males, and pairwise parameter comparisons showed that males and females differed on these paths.

Whereas females’ relationships with their parents appear to be mostly unaffected by parental internalizing problems, males’ relationships with their parents may improve when their parents experience internalizing problems. It is possible that males feel more supportive and sympathetic when their parents are exhibiting internalizing problems. That is, emerging adult male children may take on more responsibility for their family when their family experiences problems, and this role may be especially pronounced in a Southern sample where higher levels of conservatism, stricter gender roles, and higher filial piety may encourage male children to take responsibility to protect their family. These results contradict some prior literature suggesting that daughters are either equally or more likely to provide emotional support to their parents compared to sons [9, 24]. Overall, these results suggest that parental internalizing problems may enhance parent–son relationships in a way that is not elucidated fully by the current study, whereas females do not experience this effect.

Similarly, results show that mother–son relationship quality is also positively related to internalizing and externalizing problems in males. That is, just as sons may provide supportive responses to their mothers with internalizing problems, mothers also may provide the same response to their sons [32]. Specifically, sons who are struggling with emotional and behavioral problems may perceive their mothers as more caring, and mothers may be more likely than fathers to provide this additional support as a result of their role as caregiver. Alternatively, it may be the case that a close relationship between mothers and sons facilitates the transmission of psychological problems, possibly suggesting enmeshment [45].

Moreover, our results suggest major differences between parental externalizing and internalizing problems in the context of the parent–child relationship. Specifically, whereas parental internalizing problems shared small or non-significant relations with perceptions of the parent–child relationship quality, parental externalizing problems shared large negative associations with parent–child relationship quality across both genders of parents and children. These findings suggest that parental externalizing problems may be more detrimental to their relationship with their children relative to parental internalizing problems, possibly owing to the more overt nature of parental externalizing problems relative to internalizing ones. That is, children may more easily notice parental externalizing problems, and this overtness along with the nature of externalizing problems (e.g., yells, lies, gets angry) also may be more disruptive to relationship quality than internalizing problems.

Hypothesis 2 stating that parental psychopathology will be positively associated with emerging adulthood psychopathology was mostly supported. Maternal and paternal internalizing and externalizing symptoms were positively related to both male and female internalizing and externalizing symptoms in most cases, consistent with the abundance of research linking parental and child psychopathology. Contrary to hypothesis 2, paternal externalizing problems were not related to male internalizing problems, paternal internalizing problems were not related to female externalizing problems, and maternal externalizing problems were not related to female internalizing problems. It appears that the strong relations between parental and child psychological problems are attenuated across symptom domains (i.e., parental internalizing problems sometimes did not predict child externalizing problems and vice versa), which is consistent with research that more strongly links parent and child psychopathology when similar domains are examined (e.g., parent and child depression).

Hypothesis 3 predicting that parent–child relationship quality would be negatively associated with externalizing and internalizing symptomology in the youth was not supported. Maternal parent–child relationship quality was positively related to male internalizing and externalizing problems, contrary to the hypothesis, and other relations were not significant. This evidence suggests that the perception of the parent–child relationship quality in and of itself does not always directly associate with emerging adulthood psychopathology, particularly in the context of parental psychological problems. Given that all free correlations were significant as shown in Table 1, it appears that parental psychological problems accounts for much of the variance between parent–child relationship quality and emerging adult psychological problems.

Interestingly, results suggest that emerging adult males’ psychopathology may be more directly influenced by their relationship with their mother, whereas this is not the case with females or when examining fathers. Prior literature indicates that fathers may be more inclined to promote autonomy in their youth, whereas mothers tend to be more supportive [43], possibly explaining why this finding is present when examining mothers but not fathers. Overall, the current study suggests that mother–son dyads are either more supportive or enmeshed than other dyads, or that this particular dyad is especially influential in the transmission of psychopathology from parent to child.

Hypothesis 4 stated that parent–child relationship quality will mediate the relation between parental internalizing and externalizing problems and emerging internalizing and externalizing problems. Partial support for this hypothesis was found. Maternal externalizing problems had a significant indirect effect on male internalizing and externalizing problems; however, no other indirect effects were significant. When compared to the other parent–child dyads, these results suggest that maternal externalizing problems hold particular weight on the mother–son relationship, which in turn influence psychological adjustment. A possible explanation for why the indirect effects for externalizing problems were significant, whereas internalizing problems were not, is that externalizing problems are more conspicuous, whereas internalizing problems are more covert, as suggested above. Relatedly, it is possible that parental externalizing behaviors as rated on the ABCL (e.g., showing off, gets in fights, screams or yells a lot) evoke frustration or anger within the youth, whereas internalizing problems (e.g., cries a lot, worries) may evoke more sympathy or concern. The finding that only the mother–son dyad shows these indirect effects may be more complicated and is discussed further below.

Hypothesis 5 stated that the meditational effect will be conditional on gender. The gender differences found support hypothesis 5, indicating that the indirect effects are conditional on gender (i.e., they occur in males but not females). Further supporting hypothesis 5, two paths differentiated males from females as in Table 2. These paths demonstrate the unexpected positive relationships among maternal internalizing problems, the parent–child relationship, and emerging adult symptoms in the mother–son relationship as discussed in detail above. The significant gender differences found in these mediational paths statistically support moderated mediation.

Overall, our results unexpectedly suggest that males and mothers experiencing internalizing problems are more likely to have a stronger parent–child relationship. This finding could indicate responsive care from sons who feel responsible toward their parents as well as from mothers who provide support to their struggling sons. Alternatively, this finding could suggest that the mother–son dyad is more likely to experience an enmeshed relationship and/or facilitate the transmission of psychological problems. Although a definitive explanation for this particular finding is not possible, the current study emphasizes that the associations among parental psychopathology, parent–child relationship quality, and emerging adult psychopathology must be studied in the context of parent–child gender dyads. This evidence provides additional support about the complexities of parent–child dynamics, demonstrating that not all parent–child dyads should be treated and understood the same. Future research examining the specific differences within parent–child dyads would yield informative and useful results, specifically about why males tend to have better relationship quality than females with parents with internalizing problems, and how this closeness impacts transmission of psychopathology.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be viewed in the context of its limitations. Firstly, this sample consisted of college students from a Southern university; therefore, generalizability of the findings to the greater population may not be possible. In particular, high levels of conservatism present in the South are known to influence parenting and parent–child relationships. Further, these data were solely gathered through self-report of a single informant. This may be problematic in that mothers and fathers may have a different report than their children and introduces a shared-method bias. However, youth’s perceptions of their parents hold great weight on their current thoughts, behaviors, and emotions and may be just as important if not more so than actuality [49]. Further, emerging adult children are freer to report on their parents than younger children [17], and rating parents who the participants know very well has been demonstrated to provide reliable and valid ratings [1]. It is also important to note that a cross-sectional design does not allow for inferences on causality or the directionality of relations. For example, emerging adulthood internalizing and externalizing problems might be causing strains in the parent–child relationship, and might also be influencing the parents’ psychopathology (i.e., children with more psychological problems may cause their parents more stress which may lead to higher perceptions of parent psychological problems on behalf of the youth). Lastly, much prior literature has focused on parent depression impacting children (e.g., [10, 14, 18, 29]), therefore, the current study sought to examine internalizing psychopathology as a broader domain in order to encapsulate the range of internalizing problems and also make the current study more concise. Though we believe that examining the broadband scales of internalizing and externalizing problems provided meaningful information, it is likely that disentangling the different types of internalizing problems as well as the different types of externalizing problems may have yielded additional information. Thus, future research is encouraged to examine specific problem domains in addition to broad ones.

Summary

Results indicated that the relation between parental internalizing problems and the parent–child relationship quality was unexpectedly positive for males, and pairwise parameter comparisons showed that males and females significantly differed on these paths. These findings suggest that males may grow closer to their parents who exhibit internalizing problems, whereas parental internalizing problems may negatively influence parent–daughter relationship quality. These data also suggest that male emerging adult psychopathology may be more directly influenced by maternal psychopathology. Moreover, mother–child relationship quality was related positively to psychological problems in males. Mediational paths were conditional upon gender, suggesting moderated mediation. Further, higher parent–child relationship quality in the mother–son dyad was associated with higher psychopathology in both mothers and sons, possibly the result of an enmeshed relationship. Alternatively, mothers and sons may provide each other with increased support when the other experiences problems. Overall, the current study emphasizes that the complexities of parenting must be understood in the context of gender. Future research examining additional mechanisms that influence the relation between parent and child psychopathology in the context of gender would shed further light on this topic, perhaps with special focus on the mother–son dyad as well as more specific problems rather than broad psychological symptoms. Additionally, further research examining the deleterious effects of parental externalizing problems on the parent–child relationship appears warranted given the particularly large effects.

References

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2003) Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families, Burlington

Allen JP, Hauser ST (1996) Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of young adults’ states of mind regarding attachment. Dev Psychopathol 8(4):793–809

Arnett J (2000) Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 55(5):469–480

Banks T, Ninowski JE, Mash EJ, Semple DL (2008) Parenting behavior and cognitions in a community sample of mothers with and without symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Fam Stud 17(1):28–43

Baker CN, Hoerger M (2012) Parental child-rearing strategies influence self-regulation, socio-emotional adjustment, and psychopathology in early adulthood: evidence from a retrospective cohort study. Personal Individ Differ 52(7):800–805

Berg-Nielsen TS, Vikan A, Dahl AA (2002) Parenting related to child and parental psychopathology: a descriptive review of the literature. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 7(4):529–552

Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono W (2003) Parent-child conflict and the comorbidity among childhood externalizing disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(5):505–513

Byrne BM (2013) Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Campbell LD, Martin-Matthews A (2003) The gendered nature of men’s filial care. J Gerontol B 58(6):S350–S358

Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT (2005) Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46(5):479–489

Donnelly R, Renk K, McKinney C (2013) Emerging adults’ stress and health: the role of parent behaviors and cognitions. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 44(1):19–38

Downey G, Coyne JC (1990) Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychol Bull 108:50–76

Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M et al (2001) The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Dev 72(4):1112–1134

Elgar FJ, Mills RSL, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Brownridge DA (2007) Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms and child maladjustment: the mediating role of parental behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 35:943–955

Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG (1997) Genetic and environmental influences on parent–son relationships: evidence for increasing genetic influence during adolescence. Dev Psychol 33(2):351

Essex MJ, Klein MH, Cho E, Kraemer HC (2003) Exposure to maternal depression and marital conflict: gender differences in children’s later mental health symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(6):728–737

Finley GE, Mira SD, Schwartz SJ (2008) Perceived paternal and maternal involvement: factor structures, mean differences, and parental roles. Fathering 6:62–68

Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D (2011) Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(1):1–27

Gore S, Aseltine RH, Colten ME (1993) Gender, social-relational involvement, and depression. J Res Adolesc 3:101–125

Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM (2008) Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: a systematic review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47(4):379–389

Harpin VA (2005) The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child 90:9012–9017

Hayes AF (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76(4):408–420

Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, White HR (2001) The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: a prospective study. J Health Soc Behav 42(2):184–201

Houser BB, Berkman SL, Bardsley P (1985) Sex and birth order differences in filial behavior. Sex Roles 13(11):641–651

Humphreys KL, Mehta N, Lee SS (2012) Association of parental ADHD and depression with externalizing and internalizing dimensions of child psychopathology. J Atten Disord 16(4):267–275

Kane P, Garber J (2004) The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father–child conflict: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 24(3):339–360

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications, New York

Lieb R, Isensee B, Höfler M, Pfister H, Wittchen H (2002) Parental major depression and the risk of depression and other mental disorders in offspring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59(4):365–374

Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G (2000) Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 20:561–592

MacKinnon DP (2008) Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge, New York

Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG (2004) Major depression and conduct disorder in youth: associations with parental psychopathology and parent–child conflict. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45(2):377–386

McKinney C, Milone MC (2012) Parental and late adolescent psychopathology: mothers may provide support when needed most. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 43(5):747–760

McClure EB, Brennan PA, Hammen C, Le Brocque RM (2001) Parental anxiety disorders, child anxiety disorders, and the perceived parent–child relationship in an Australian high-risk sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol 29(1):1–10

Middleton M, Scott SL, Renk K (2009) Parental depression, parenting behaviours, and behaviour problems in young children. Infant Child Dev 18(4):323–336

Nagin D, Tremblay RE (2001). Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: a group based method. Psychol Methods 6:618–634

Ninowski JE, Mash EJ, Benzies KM (2007) Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in first-time expectant women: relations with parenting cognitions and behaviors. Infant Ment Health J 28(1):54–75

Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC (2007) Lifetime prevalence, correlates and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48(7):703–713

Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Bucholz KK, Schuckit MA, Nurnberger JI (2005) The relationship between parental psychopathology and adolescent psychopathology: an examination of gender patterns. J Emot Behav Disord 13(2):67–76

Phares V, Compas BE (1992) The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: make room for Daddy. Psychol Bull 111:387–412

Reinherz H, Giaconia RM, Carmola AM, Wasserman M, Paradis AD (2000) General and specific childhood risk factors for depression and drug disorders by early adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39(2):223–231

Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE (2002) Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull 128(2):330–366

Roisman GI, Madsden SD, Henninghausen KH, Collins LA (2001) The coherence of dyadic behavior across parent-child and romantic relationships as mediated by the internalized representation of experience. Attach Hum Dev 3(2):156–172

van der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJM, Bogels SM, Paulussen-Hoogeboom MC (2010) Parenting behavior as a mediator between young children’s negative emotionality and their anxiety/depression. Infant Child Dev 19:354–365

Verbeek T, Bockting CL, van Pampus MG, Ormel J, Meijer JL, Hartman CA, Burger H (2012) Postpartum depression predicts offspring mental health problems in adolescence independently of parental lifetime psychopathology. J Affect Disord 136(3):948–954

Walker CS, McKinney C (2015) Parental and emerging adult psychopathology: moderated mediation by gender and affect toward parents. J Adolesc 44:158–167

Walsh C, MacMillan H, Jamieson E (2002) The relationship between parental psychiatric disorder and child physical and sexual abuse: findings from the Ontario health supplement. Child Abuse Negl 26(1):11–22

Watkins SJ, Mash EJ (2009) Sub-clinical levels of symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and self-reported parental cognitions and behaviours in mothers of young infants. J Reprod Infant Psychol 27(1):70–88

Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H (2006) Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry 163(6):1001–1008

Yahav R (2007) The relationship between children’s and adolescent’s perceptions of parenting style and internal and external symptoms. Child Care Health Dev 33:460–471

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Franz, A.O., McKinney, C. Parental and Child Psychopathology: Moderated Mediation by Gender and Parent–Child Relationship Quality. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 49, 843–852 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0801-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0801-0