Abstract

Despite significant functional problems in multiple domains, children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) unexpectedly provide extremely positive reports of their own competence in comparison to other criteria reflecting actual competence. This counterintuitive phenomenon is known as the positive illusory bias (PIB). This article provides a comprehensive and critical review of the literature examining the self-perceptions of children with ADHD and the PIB. Specifically, we analyze methodological and statistical challenges associated with the investigation of the phenomenon, the theoretical basis for the PIB, and the effects of sample heterogeneity on self-perception patterns. We conclude by discussing the implications of this work and providing recommendations for advancing research in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As one of the most prevalent childhood mental health disorders, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) affects an estimated 3–7% of all school-aged children (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Diagnosed considerably more often in males, ADHD is characterized by developmentally inappropriate hyperactive/impulsive and/or inattentive symptoms that result in impairment in multiple settings (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Children with ADHD consistently have been found to display academic difficulties (LeFever et al. 2002), social deficits (Pelham and Bender 1982), and behavior problems (Barkley 1990). Within the academic domain, children with ADHD typically have poorer academic achievement scores (Hinshaw 1992), lower grades (Cantwell and Satterfield 1978) and less persistence on school-related tasks than their non-impaired peers (Hoza et al. 2001). Within the social domain, children with ADHD have fewer close friendships (Bagwell et al. 2001), are more rejected in the classroom (Hodgens et al. 2000; Hoza et al. 2005), and have more negative interactions with their mothers as compared to their peers without ADHD (Cunningham and Barkley 1979). Within the behavioral domain, the most noticeable deficits include aggression (Loney and Milich 1982) and noncompliance with adult commands (Danforth et al. 1991). Given the above-described deficits, this population is at increased risk for school dropout, drug abuse, and juvenile delinquency (Shaffer 1994).

Despite these findings of chronic functional problems in academic, social, and behavioral domains, many children with ADHD tend to underreport the presence of these problems. Indeed, a growing body of literature suggests that many children with ADHD actually overestimate their own competence in comparison to other criteria reflecting actual competence (e.g., Hoza et al. 2004; Hoza et al. 2002). In other words, within this population, children’s self-perceptions frequently do not correspond with objective measures of performance or with parent and teacher ratings of competence. This phenomenon has been termed the positive illusory bias (PIB) and is operationally defined as a disparity between self-report of competence and actual competence such that self-reported competence is substantially higher than actual competence (Hoza et al. 2002).

Interestingly, social psychology research has documented the existence of similar positive illusions in the general population. For example, multiple studies have produced consistent evidence of the “better than average” effect (e.g., Alicke and Govorun 2005). When adults are asked to compare themselves to a hypothetical “average” target, self-evaluations are typically more positive than mathematically possible. In addition, a review by Taylor and Brown (1988) suggested that mentally healthy individuals hold unrealistically positive self-evaluations, inflated beliefs of power over the environment, and exaggerated optimism about the future.

Thus, moderately positive illusory beliefs appear to be somewhat normative. However, the PIB found in children with ADHD differs from the overly positive cognitions found in the general population in three ways. First, the discrepancy between perceived and actual competence typically is of greater magnitude in samples of children with ADHD as compared to children without ADHD (Hoza et al. 2002; Owens and Hoza 2003), and thus deviates from normative positive cognitions. That is, children with ADHD report positive illusory levels of self-competence that exceed those of similarly aged, non-diagnosed peers. Indeed, past researchers have suggested that excessively inflated self-perceptions may differ qualitatively from the moderately enhanced self-evaluations exhibited in the general population (e.g., Baumeister 1989; Taylor and Armor 1996). Second, Taylor and Brown (1988) suggested that moderate positive illusions are adaptive in that they enhance motivation, performance, and task persistence. This does not seem to be true for the positive illusions held by children with ADHD. Despite demonstrating positive illusory self-perceptions, children with ADHD tend to give up more frequently on tasks and perform worse than their non-ADHD peers (Hoza et al. 2001; O’Neill and Douglas 1991).

Third, within the context of other theoretical models, the PIB in children with ADHD seems to be a unique and counterintuitive phenomenon. For example, Harter’s model of motivation (1981) purports that children’s self-perceptions of competence and control contribute to their motivational orientation. More specifically, children who experience success following task engagement develop an enhanced sense of self-efficacy. As a result, these children are motivated to engage in future challenging tasks and are subsequently reinforced by additional success. Conversely, children who experience failure on a given task develop a lower sense of self-competence and thus are less likely to participate in future challenging tasks. Since most children with ADHD have been found to experience failure in multiple domains, Harter’s (1981) model would suggest that these children are at risk for developing a low sense of self-competence. However, most studies that have examined self-perceptions in children with ADHD have found evidence inconsistent with Harter’s model, suggesting that there is something unique about the self-system of children with ADHD. Specifically, past results imply that children with ADHD have unrealistically high self-views of skills and competencies, despite histories marked with failure in numerous domains (e.g., Hoza et al. 2002). On one hand, such positive illusory self-views may render children with ADHD more susceptible to failure, as these views likely prevent children from recognizing the need for improvement, acknowledging negative feedback, and altering their approach to task completion (Milich and Okazaki 1991). On the other hand, if children with ADHD do not perceive their academic and social failures, this lack of awareness may spare their self-confidence, protect their self-esteem, and ward off negative affect. As this review article highlights, additional research examining the relative adaptive or maladaptive consequences of positive illusory self-perceptions upon social-emotional functioning and task performance and persistence is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn in this area.

We acknowledge that overly positive self-evaluations are not exclusive to children with ADHD and have been found in other non-clinic samples (e.g., Gresham et al. 1998; Heath and Glen 2005; Hymel et al. 1993). Nonetheless, for several reasons, the current article will primarily focus on the positive illusory self-perceptions of children with ADHD. First, the pattern of differences between children with ADHD and asymptomatic control children has been replicated across multiple studies and laboratories. These studies represent a rich and coherent literature that warrants synthesis and critical analysis. Since this literature is focused on a well-defined sample, recommendations produced by such an analysis can be focused and directive. Second, a closer examination of the studies that have found a similar pattern of positive illusory self-concepts in non-clinic samples of children reveals a common behavioral characteristic. Although the focus of these studies may have been children with poor social status, learning disabilities, or aggressive behavior (Gresham et al. 1998; Heath and Glen 2005; Hymel et al. 1993), disruptive behavior problems are a common factor linking all of these samples. Thus, to date extant research does not specify the degree to which positive illusions are specific to any one population. However, most research suggests that the PIB is linked to characteristics associated with ADHD. Given the coherence of the literature focused on this disorder, we will contain this review to samples of children with ADHD or clearly defined ADHD symptoms. Finally, ADHD is a disorder for which evidence-based behavioral treatments have been identified. There is suggestive evidence that awareness of one’s own deficits may serve a motivating function in behavioral treatment (Hoza and Pelham 1995), whereas inaccurate estimations of self-competence may interfere with treatment progress. Thus, a better understanding of the self-system of children with ADHD may have implications for future enhancements to evidence-based treatment for this population.

The goal of this article is to provide a comprehensive and critical review of the literature examining the self-perceptions of children with ADHD. Our synthesis and analysis of the literature was guided by three overarching questions: Is the PIB present in the self-perceptions of children with ADHD? What is the function (or explanation) of the PIB in children with ADHD? And, is the PIB adaptive or maladaptive in children with ADHD? Our understanding of the latter two questions will guide our interpretation of the data associated with the first question. That is, simply identifying the existence of the PIB is not enough. Research in this area must strive to understand the underlying mechanism or function of the bias, as well as the short- and long-term consequences of this pattern of self-perceptions; both of these issues might have important implications for treatment modifications.

Thus, first we review the extant literature that provides substantial empirical support for the presence of the PIB in children with ADHD. In doing so, we highlight critical methodological and statistical challenges associated with the investigation of the phenomenon. Next, to create a conceptual context for stimulating new ideas and advancing research regarding the underlying mechanisms of the PIB, we review the data that explore the possible functions of the phenomenon, as well as the effects of sample heterogeneity on patterns of self-perceptions. To date, the adaptiveness of the PIB is unclear. Thus, in the absence of longitudinal studies examining the implications of the short- and long-term effects of this perceptual style, we can only speculate with regard to possible consequences of the PIB and suggest how future studies can explore this issue. Thus, we conclude by discussing the implications of this work and offering recommendations for future studies. We hope that this review will ignite interest and provide guidance in research that attempts to obtain a better conceptualization of self-perceptual patterns in children with ADHD.

Self-perceptions and Children with ADHD

The methodology used to examine the self-perceptions of children with ADHD has evolved over the last decade. Early research compared ratings of competence on self-perception measures (i.e., absolute rating scale scores), predictions of performance on various tasks, and post-performance self-evaluation ratings among children with and without ADHD. These early studies highlighted unique patterns in children’s self-perceptions and provided preliminary evidence to suggest that the self-perceptions of children with ADHD were less congruent with actual performance than were those of control children. In order examine the self-perceptions within this population, more recent studies have investigated discrepancies between children’s self-perceived competence and competence as indexed by standardized achievement measures or parent and teacher ratings. These studies provide additional support for the existence of a PIB in children with ADHD. More recently, researchers have begun to examine the role of ADHD subtype, comorbidity, and gender in the self-perception patterns of children with ADHD. Below, we synthesize the findings of these methodological approaches in order of methodological strength (i.e., studies with weaker methodology are reviewed first), including studies that make use of (a) absolute self-perception scores (mean scores) in the absence of a criterion for comparison, (b) pre-task prediction and/or post-task performance evaluation ratings, and (c) discrepancy analyses utilizing a criterion to calculate the discrepancy between child-reported competence and actual competence. See Table 1 for a summary of all studies examining the PIB in children with ADHD. Following this analysis, we further discuss methodological and statistical challenges associated with examining the PIB in children with ADHD.

Absolute Self-perceptions

In one of the first studies to compare the self-perceptions of boys with and without ADHD, Hoza et al. (1993) utilized the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter 1985) to assess children’s self-perceptions of scholastic competence, social acceptance, behavioral conduct, athletic competence, physical appearance, and global self-worth. After controlling for comorbid internalizing symptoms, Hoza et al. found that the self-perceptions of boys with ADHD were not significantly different from those of boys without ADHD across all domains, with the exception of athletic competence in which boys with ADHD provided more positive self-evaluations than boys without ADHD. Notably, the boys with ADHD in this sample were enrolled in intensive day treatment and thus presumably demonstrating significant functional problems. Consequently, the authors interpreted these findings as evidence of self-enhancement on the part of the boys with ADHD. Data from more recent studies with larger sample sizes have replicated this pattern (e.g., Hoza et al. 2002).

Conversely, two studies (Horn et al. 1989; Ialongo et al. 1994) found that children with ADHD reported significantly lower self-concepts than did control children. However, there are several possible explanations for the inconsistency between these findings and those of Hoza et al. (2002, 1993). First, Horn et al. (1989) and Ialongo and colleagues (1994) utilized the Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale (Piers 1969), whereas most other studies (e.g., Hoza et al. 2002, 1993) utilized the SPPC (Harter 1985). It may be that between-group differences in self-perceptions are better detected when a more sensitive dimensional assessment method (e.g., SPPC) is used compared to a dichotomous assessment method (e.g., Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale). Second, Horn and colleagues (1989) only administered the anxiety, happiness, and popularity subscales of the Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale, excluding more salient domains such as behavior and academics. Finally, Horn et al. (1989) did not control for internalizing symptoms, whereas Hoza et al. (1993) did control for internalizing symptoms. Importantly, there is some evidence to support the idea that comorbid mood problems (and authors’ decisions about how to assess these symptoms) are quite relevant to findings about self-perceptions; we discuss this issue in detail later in the article.Footnote 1

In sum, studies examining the absolute self-perceptions of children with ADHD have generated mixed results. However, these studies provide the weakest support for the PIB because without a basis for comparison, the congruence between children’s perceptions and actual competence is unknown. In an attempt to advance the literature, other studies have utilized children’s predictions of their future task performance and post-task performance evaluations in order to determine the presence of a PIB.

Pre-task Prediction and Post-performance Ratings

Many of the early studies examining pre-task predictions and post-task performance evaluations made by children with ADHD revealed a glaring optimism in both arenas. For example, Whalen et al. (1991) found that 80% of boys with ADHD predicted perfect performance on a word-search task compared to 43% of boys without ADHD. Another study demonstrated that despite similar performance (i.e., no significant group difference) on a story recall task, children with ADHD reported higher pre-task predictions than control children (O’Neill and Douglas 1991). Additionally, boys with ADHD studied for less time, appeared to exert less effort, and utilized less effective strategies relative to control boys. Milich and Okazaki (1991) obtained similar results when evaluating the predictions of boys with and without ADHD prior to solving a set of find-a-word puzzles. Boys with ADHD predicted better self-performance, yet completed considerably fewer puzzles than controls. Boys with ADHD also reported more frustration and gave up more frequently than boys without ADHD.

Similarly, findings from several other studies employing success-failure manipulation tasks imply that children with ADHD are overly optimistic in their post-task performance evaluations. Hoza et al. (2000) examined children’s self-evaluations of performance in a success-failure manipulation task within the social domain using a “get-acquainted” task. Boys with and without ADHD were instructed to get a child confederate to like them and to convince the confederate to come to a camp (or school). Performance was manipulated with the help of the confederate, such that each child participated in a successful and unsuccessful social interaction. Coders who were unaware of group status evaluated boys with ADHD as less socially competent than boys without ADHD across both success and failure conditions. Importantly, despite these objective indices of relative incompetence at the task, boys with ADHD evaluated their own task performance as significantly better than did control boys. This overestimation was most evident after experiencing a failed social interaction.

Hoza et al. (2001) expanded upon the previous study (Hoza et al. 2000) by examining children’s self-evaluations of performance in the context of success and failure experiences in the academic domain (i.e., find-a-word puzzles). Despite the fact that boys with ADHD solved fewer test puzzles, gave up more often, and were rated by objective evaluators to be less effortful, their post-task evaluations were not significantly different from those of control children. These findings suggest that the self-evaluation ratings of children with ADHD were not commensurate with their actual performance. More specifically, boys with ADHD provided overly optimistic reports of their own performance.

Clearly, the studies described in this section represent a methodological improvement over using absolute self-perceptions scores in the absence of a criterion. As such, future research should continue to explore critical questions related to the PIB in the context of such methodology (i.e., using performance on a specific task as the basis for children’s ratings of competence and the competence criterion). In the next section, we discuss another methodological improvement over the use of absolute self-perceptions; the use of discrepancy scores that index the congruence between the child’s perceptions of competence and other estimates of actual competence across multiple domains.

Discrepancy and Criterion Analysis

Recent studies have utilized discrepancy analyses in which difference scores are calculated by subtracting a criterion score (e.g., teacher report) from the child’s self-report of competence. Difference scores are then compared between children with and without ADHD. Across studies, mother, father, and teacher reports of competence across multiple domains have been used as comparison criteria, and scores on standardized academic achievement tests.

Hoza et al. (2002) examined the self-perceptions of boys with and without ADHD by comparing the boys’ self-report on the SPPC (Harter 1985) against teacher report on the parallel teacher version (Teacher Report of Child’s Actual Behavior; Harter 1985). Relative to teacher report, boys with ADHD overestimated their academic, behavioral, and social abilities to a greater degree than did control boys. In a more recent study, Hoza et al. (2004), further advanced the literature by demonstrating that the PIB was present in both boys and girls with ADHD and that the bias was observed regardless of the informant ratings used as the criterion (i.e., mothers, fathers, and teachers), ruling out potential rater bias on the part of teachers as an explanation for the phenomenon. Interestingly, two studies (Hoza et al. 2004, 2002) have provided evidence that children with ADHD demonstrate the greatest overestimation of competence in their domain of greatest deficit.

To date, Owens and Hoza’s (2003) study is the only investigation of the role of ADHD subtype (Predominantly Inattentive Type [IA] versus Hyperactive/Impulsive and/or Combined Types [HICB]) in self-perceptions of competence in the academic domain. The effect of ADHD subtype will be discussed in more detail in the Effects of Sample Heterogeneity section; however, it is noteworthy that Owens and Hoza employed a discrepancy analysis with teacher report and standardized achievement tests used as the criterion. Boys and girls in the HICB group overestimated their scholastic competence more than control boys when math and reading achievement scores were used as the criterion. Boys and girls in the IA group, however, provided estimates of their own academic competence that were more congruent with the criterion. Moreover, regression analyses indicated that greater overestimation of scholastic competence was associated with more severe hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, but not more severe inattentive symptoms, suggesting that children in the IA group were not simply overlooking (e.g., failing to perceive due to attentional difficulties) their underperformance.

Measurement, Methodological, and Statistical Issues Related to the PIB

Over time, studies investigating the PIB in children with ADHD have made methodological improvements. Nonetheless, methodological and statistical limitations remain. In this section, we discuss challenges in assessing the PIB in children with ADHD, delineate current methodological and statistical approaches, and highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. We conclude by making suggestions that may guide future inquiry in this area.

Rater Bias in Competence Measurement

As previously discussed, due to the methodological limitations of analyzing absolute self-perception scores (e.g., Gresham et al. 1998; Hoza et al. 2002) and as an attempt to better evaluate the accuracy of self-perceptions, researchers have examined self-perceptions in comparison to criteria that presumably provide more objective indices of children’s actual competencies (Hoza et al. 2002). Many studies examining the PIB have relied on teacher report as a criterion against which to compare children’s self-perceptions. One might argue that the overly inflated self-perceptions of children with ADHD are a result of rater bias on the part of the teacher providing the criterion rating. That is, teachers may provide overly negative evaluations given the difficulties that teachers experience with children with ADHD; consequently, the self-perceptions of children with ADHD would appear inflated. However, a recent study addressed this concern by obtaining ratings of competence from teachers, mothers, and fathers (Hoza et al. 2004). The PIB was found in children with ADHD across all raters, but was not evident for control children. Hoza et al. (2004) findings provide greater confirmation that the self-perceptions of children with ADHD are positive illusory and suggest that the PIB is not simply an artifact of rater bias on the part of the teacher. It is also possible that both parents’ and teachers’ perceptions could be negatively biased, leading to overestimation on the part of the child with ADHD. However, additional studies comparing children’s self-perceptions to more objective criteria such as achievement scores or lab task performance also report positive illusions in ADHD samples (e.g., Ohan and Johnston 2002; Owens and Hoza 2003). These findings confirm that rater bias alone (whether on the part of a teacher or parent) is not an adequate explanation for these findings. Nonetheless, future research that incorporates objective criteria, including standardized tests, actual task performance, and competency estimates made by more objective raters (i.e., observers who are unaware of diagnostic status) would be helpful in confirming this point.

Challenges to Difference Score Approaches

To date, the majority of research investigating the PIB in children with ADHD employs statistical difference scores that index the discrepancy between children’s perceptions of competence and actual competence. Studies investigating the PIB have utilized both unstandardized and standardized difference scores (e.g., Owens and Hoza 2003). We acknowledge that difference scores are not without limitations. Criticisms of the use of difference scores center around two primary themes. First, the reliability of a difference score typically is substantially lower than are the reliabilities of the variables employed to construct the discrepancy as a result of combined measurement error (Edwards 2001). The low reliability of difference scores then results in an increased likelihood of making a Type II error, or failure to detect in the sample the presence of a meaningful relationship between the discrepancy score and relevant outcome variables that exist in the population (Edwards 2001).

Second, difference scores have a tendency to be strongly and systematically correlated with their components (e.g., Cronbach 1958; Zuckerman and Knee 1996). These correlations, then, may result in the detection of significant relations between difference scores and dependent variables that actually are reflective of a relation between one of the difference score’s component variables and the dependent variables, rather than being indicative of any predictive ability of the discrepancy score itself (Cronbach 1958). For this reason, the use of difference scores may make it difficult to piece apart the meaning of statistically significant relationships. For example, Griffin et al. (1999) argue that correlations between difference scores and other variables may reflect any number of underlying patterns among component and outcome variables. Many researchers have further contended that difference scores are linearly related to their components, such that any difference score is no more than the sum of its constituent parts (Zuckerman and Knee 1996). Based on this argument, critics of the discrepancy construct have maintained that utilizing component variables is more parsimonious than using difference scores (Cronbach 1958).

A more simplistic limitation of the difference score is that children with ADHD are mathematically more likely to overestimate their competence than are control children simply as a function of their lower levels of actual competence. In other words, due to the true impairments on the part of children with ADHD, the criterion scores (e.g., actual achievement scores) almost certainly will be much lower for children with ADHD than for control children. As a result, it is much easier for children with ADHD to overestimate their competence compared to control children (i.e., the potential “gap” is much larger for children with ADHD). Similarly, there may be a ceiling effect for control children such that they may not be able to mathematically overestimate their competence if their score on the competence criterion is already high.

Despite these limitations of difference scores, there are several marked advantages to their use. Difference score advocates have addressed concerns about the validity of the discrepancy score construct by arguing for the importance of conceptual validity over that of statistical validity. Researchers endorsing this viewpoint contend that discrepancy scores represent constructs that are theoretically distinct from the constructs represented by the component variables (Tisak and Smith 1994a, b). Colvin et al. (1996) asserted that for this reason, construction of difference scores facilitates a different type of parsimony than that advocated by opponents of the difference score construct. They noted that difference scores provide researchers with the opportunity to investigate the concepts that might otherwise be “awkward to assess, comprehend, and evaluate” (Colvin et al. 1996, p. 1253). This certainly seems to be the case when examining the relative accuracy of children’s self-perceptions.

In addition, Tisak and Smith (1994a) contended that although difference scores as a category may be prone to low reliability, reliability should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Rogosa et al. (1984) noted that even difference scores with low reliability might still have utility. In fact, it has been argued that if difference scores do indeed possess low reliability, the effect of this reduced reliability will be to attenuate statistical correlations with other variables. Statistically significant results therefore would serve as conservative estimates of relations between difference scores and other variables (Colvin et al. 1996).

Alternative Statistical Methodologies

Given the challenges and limitations associated with the use of difference scores, alternative statistical methodologies warrant discussion and exploration. Other researchers have employed residual difference scores to investigate similar constructs. These scores are generated through regression analyses that employ one informant (i.e., the child) as a predictor of the other informant (i.e., teacher, parent, or objective criterion assessing actual competence). A residual difference score indexing the difference between the score predicted by the independent variable (child) and that provided by the dependent variable (criterion) is generated by the regression analysis, and this score typically is converted into a z-score (see Chi and Hinshaw 2002; De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2004). However, we note that the drawback of this statistical approach is that the best-fitting regression line divides the sample roughly in half, with approximately 50% of cases lying above the line and 50% lying below it. Hence, this approach will always result in a distribution of scores composed of approximately 50% underestimators and 50% overestimators. However, in samples for which this assumed equal distribution of overestimators and underestimators does not hold (for example, children with ADHD), residual difference scores consequently may misrepresent the data.

A recent review (De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2004) examined the most commonly used methods for comparing informant ratings in child psychopathology; these authors recommended the use of standardized difference scores. More specifically, the authors evaluated three informant discrepancy methods, including unstandardized difference scores among two informants’ ratings, standardized difference scores among two informants’ ratings, and the residual difference between two informants’ ratings. The standardized difference score measure was the only method that was uniformly correlated with the ratings from which it was computed. More specifically, standardization of the component scores prior to computing the discrepancy associates the discrepancy score with both component parts, which alleviates concerns about construct validity. Future studies should investigate other analyses that may best evaluate the accuracy of self-perceptions while minimizing methodological limitations. Although there are limitations to using discrepancy analyses, the alternatives also have significant limitations. Thus, we concur with De Los Reyes and Kazdin (2004) in recommending that researchers employ standardized discrepancy scores when conducting evaluations of children’s self-perceptions.

Theoretical Explanations for the Positive Illusory Bias

The PIB in the self-perceptions of children with ADHD has been well documented; however, the function and causes of this phenomenon are unclear. Hypothesized explanations for the PIB include cognitive immaturity (Milich 1994), neuropsychological deficits (Owens and Hoza 2003), ignorance of incompetence (Hoza et al. 2002), and self-protection (Ohan and Johnston 2002). We acknowledge that these hypotheses may not be mutually exclusive. Indeed, because the mechanisms underlying the PIB are not yet well understood, and thus not yet well-articulated, there is overlap in the various constructs that past researchers have proposed to explain the function of the PIB. Given the existing data (or lack thereof), the goal of this section is not to provide definitive answers, but rather to provide a conceptual context for stimulating new ideas and advancing research regarding the underlying mechanisms of the PIB. The following discussion presents current empirical evidence supporting or disconfirming each of the possible explanations presented in the literature till date.

Cognitive Immaturity

Compared to older children, younger children tend to overestimate their skills in various academic tasks, and overestimate their future performance, and purportedly this overestimation serves as an adaptive purpose (Bjorklund and Green 1992). For example, by definition, young children experience frequent failure as they continuously encounter novel tasks. Young children’s optimistic beliefs about their ability to succeed allow them to try new activities and persist on challenging tasks. Since children with ADHD often are characterized as being behaviorally and cognitively immature (Whalen 1989), it has been suggested that cognitive immaturity may explain their positive illusory self-perceptions (Milich 1994). That is, the PIB found in children with ADHD may be analogous to the overestimation of self-competence evident in young children because both types of children have immature cognitive functions. This hypothesis, thus, implies that children with ADHD, like the general population of young children, will outgrow this bias in cognitions.

Direct empirical support for this hypothesis is quite limited (Milich 1994). Upto date, no study has directly examined the cognitive immaturity hypothesis in the positive illusory self-perceptions of children with ADHD. Moreover, no study has examined the presence of the PIB in a longitudinal sample or in a cross-sectional sample with ages that span early childhood to young adulthood. As such, the role of development in the expression of the PIB is largely unknown. In order to sufficiently examine the cognitive immaturity hypothesis, both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies are needed. Thus, conclusions about the cognitive immaturity hypothesis can only be drawn indirectly from extant data.

For example, if the PIB in children with ADHD was analogous to the optimism of young children, such optimism would result in continued persistence during challenging tasks. In contrast, several studies suggest that optimistic self-perceptions in children with ADHD do not result in continued persistence (Hoza et al. 2001; Milich 1994). Instead, Milich (1994) characterized the performance behavior of children with ADHD as being consistent with learned helplessness, despite the presence of optimistic assessments of self-competence. This indirect evidence challenges the viability of cognitive immaturity as the best explanation for the PIB.

Neuropsychological Deficits

Neuroimaging studies suggest that there are four main neural regions associated with ADHD. These regions include the (a) prefrontal cortices, (b) basal ganglia, (c) cerebellum, and (d) corpus callosum (Nigg 2006). There is preliminary evidence that children with ADHD have abnormal patterns of brain activation during challenging tasks that require the use of these four structures. The four neural regions listed above all also are related to executive functioning, and not surprisingly, neuropsychological research suggests that children with ADHD demonstrate executive functioning deficits (e.g., Murphy et al. 2001; Swanson et al. 1998; Tannock 1998).

Anosognosia is a neurologically based lack of awareness of personal errors (Stuss and Benson 1987) and impairments in self-awareness (Ownsworth et al. 2002; Starkstein et al. 2006) that is linked to frontal lobe damage and executive dysfunction. Patients who have frontal lobe damage and executive dysfunction are unable to self-monitor and regulate their behavior (Stuss and Benson 1987) and often overestimate their abilities, despite maintaining the ability to evaluate the competence of their spouses (e.g., Duke et al. 2002; Kaszniak and Christensen 1995). Taken together, it is possible that the unique pattern of self-perceptions, self-monitoring, and self-awareness found in children with ADHD may be the result of some form of an anosognosia-like condition, stemming from executive dysfunction. If this were the case, consistent with research on anosognosia in adult patients (e.g., Duke et al. 2002), children with ADHD would have difficulty accurately evaluating their own competence, but would be capable of accurately evaluating the competence of others. Further, this pattern of competence evaluation would be more extreme in children with ADHD who demonstrate greater executive functioning deficits (as assessed by standardized tests of executive functioning) than those with less impairment in these areas. Unfortunately, no study has examined the relation between executive dysfunction and the PIB. Given the current state of knowledge, we cannot determine the relation among executive dysfunction, the PIB, and ADHD. However, the prominent role of executive dysfunction in the manifestation of ADHD makes this an area worthy of future research.

Ignorance of Incompetence Hypothesis

According to Kruger and Dunning (1999), individuals who are incompetent in a given domain “suffer a dual burden: not only do they reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of their ability to realize it” (p. 1121). This phenomenon has been labeled ignorance of incompetence (Dunning et al. 2003; Kruger and Dunning 1999). Since children with ADHD demonstrate chronic and significant deficits (e.g., Barkley 1990; Pelham and Bender 1982; LeFever et al. 2002), it might be argued that these children are incompetent across multiple domains. As such, ignorance of incompetence may be a plausible explanation for the overly optimistic self-assessments of children with ADHD. If applied to children with ADHD, this hypothesis would suggest that overly inflated self-perceptions of children with ADHD might be a result of their inability to recognize their deficits precisely because they are incompetent and lack skills. For instance, a child with ADHD who lacks social skills will not be able to accurately evaluate why he or she could not maintain a friendship. However, in contrast to the executive function hypothesis (anosognosia) in which the child with ADHD would have difficulty accurately evaluating their own competence, but would be capable of accurately evaluating the competence of others, the ignorance of incompetence hypothesis implies that the child would be a poor evaluator of both self-competence and the competence of others. Upto date, no studies have directly tested the ignorance of incompetence hypothesis (i.e., replicated the methodology of Kruger and Dunning 1999) in children with ADHD. Nonetheless, we present some preliminary confirming and disconfirming evidence for this hypothesis as an explanation for the PIB in children with ADHD.

In support of the ignorance of incompetence hypothesis, Hoza et al. (2004, 2002) have found that children with ADHD overestimate their competence the most in their domain(s) of greatest deficit. For example, children with ADHD and comorbid aggression tended to overestimate their competence the most in the social acceptance and behavioral conduct domains; whereas children with ADHD and comorbid low achievement tended to overestimate their competence the most in the scholastic competence domain. As such, Hoza et al. (2002) speculated that children with ADHD may not have the knowledge to evaluate competence if they are significantly impaired in a given domain (i.e., if these children do not have the skills necessary to succeed in the specified domain, they also do not possess the skills necessary to evaluate their competence in that domain).

Conversely, in Owens and Hoza’s (2003) study, HICB children were no more impaired in the academic domain (i.e., as assessed by standardized achievement tests) than were IA children; yet HICB children overestimated their academic self-competence significantly more than IA children. If the ignorance of incompetence hypothesis was applicable to the PIB in ADHD, it would be expected that IA children would also demonstrate inflated perceptions of scholastic competence because IA children were as equally impaired academically as HICB children. Further, performance estimates of children with ADHD have been shown to decrease following positive feedback in the social domain (Diener and Milich 1997; Ohan and Johnston 2002). The ignorance of incompetence hypothesis cannot explain why the performance estimates of children with ADHD become more aligned with actual performance after receiving positive feedback.

Lastly, Evangelista et al. (2007) found that children with ADHD were accurate (i.e., not significantly different from control children) in evaluating other children’s competence in success and failure situations in both academic and social domains; yet, children with ADHD overestimated their own competence relative to teachers’ perceptions across multiple domains significantly more than the control children did. These findings suggest that children with ADHD likely have the skills to evaluate the competence of others across multiple domains, even in domains in which they experience significant deficits. According to the ignorance of incompetence hypothesis, individuals who are incompetent in a given domain and lack the skills to evaluate competency in this domain that should not be able to evaluate the competency of themselves or others (Dunning et al. 2003). As such, Evangelista and colleagues’ (2007) study provides the most convincing evidence that disconfirms the ignorance of incompetence hypothesis as the most viable explanation for the PIB in children with ADHD. Future studies should replicate the methodology used by Kruger and Dunning (1999) to further explore this hypothesis.

Self-protective Hypothesis

The self-protective hypothesis posits that, when children with ADHD are threatened by a challenging task, they attempt to hide their incompetence and prevent feelings of failure or inadequacy by inflating reports of self-competence (Diener and Milich 1997). In other words, this hypothesis suggests that children with ADHD overestimate their competence as a coping mechanism that presents a confident front to others and allows children to protect their self-esteem. This explanation is consistent with Hoza et al. (2004, 2002) findings that children with ADHD overestimated their competence the most in the domain of greatest deficit. Evangelista et al. (2007) findings also provide support for the self-protective hypothesis. Namely, children with ADHD inflated reports of their own competence, but not the competence of others (i.e., consistent with the idea that there is no need for self-protection when rating another person’s competence). Taken together, these findings (Evangelista et al. 2007; Hoza et al. 2004, 2002) lend preliminary support to the self-protective hypothesis.

Additional research that has directly tested the self-protective hypothesis offers more substantive confirming evidence. For example, Diener and Milich (1997) tested the self-protective hypothesis in boys with ADHD within the social domain. Diener and Milich reasoned that boys with ADHD who receive positive feedback about their social performance would lower their performance estimates, as they would no longer feel the need to bolster their self-perceptions (i.e., self-protect) once positive feedback was received. Boys with ADHD and non-impaired control boys engaged in a social interaction task with an unfamiliar peer. Boys were randomly assigned to either a positive feedback or no feedback condition. Results supported the hypothesis such that boys with ADHD who received positive feedback lowered their self-perceptions of social performance, whereas boys with ADHD who received no feedback increased their self-perceptions of social performance. The opposite pattern was observed in non-impaired control boys. More specifically, after positive feedback, non-impaired control boys increased their self-perceptions of social performance, whereas after no feedback, non-impaired control boys decreased their self-perceptions of social performance. These results suggested that boys with ADHD do not feel the need to enhance their reports of self-competence once positive feedback is given (i.e., they have proven their competence and/or warded off feelings of inadequacy), lending support to the self-protective hypothesis.

Ohan and Johnston (2002) expanded on the previous study’s methodology by testing the self-protective hypothesis in boys with ADHD in both academic and social domains. Similar to Diener and Milich (1997), Ohan and Johnston hypothesized that boys with ADHD would lower their reports of self-competence after receiving positive feedback about their performance on a maze task with a confederate (i.e., teacher). Performance on the maze task represented the academic domain and the interaction with the confederate teacher represented performance in the social domain. Participants were assigned to positive feedback, no feedback, or average feedback conditions. Consistent with Diener and Milich (1997), results revealed that boys with ADHD lowered their self-perceptions of social performance following positive feedback; whereas boys without ADHD did not (Ohan and Johnston 2002). Conversely, there were no differences in self-perceptions of social performance between boys with and without ADHD who received average or no feedback. Unexpectedly, there was a different pattern of results for the academic domain. More specifically, both groups of boys increased their self-perceptions after receiving positive feedback. Thus, results provide additional support for the self-protective hypothesis in the social domain; however, such support was not replicated in the academic domain.

It is possible that the mechanism behind the PIB in children with ADHD varies depending on the domain. In other words, children with ADHD may believe that social competence is more important than academic competence; as a result, they may feel the need to self-protect to a greater extent in the social domain. However, it is also possible that methodological limitations in the Ohan and Johnston (2002) study contributed to the inconsistency of findings across domains. For example, it is arguable that the academic task utilized in the study (i.e., the maze task) was not viewed by the children as an ecologically valid academic task. In addition, performance representing the academic and social domains was drawn from one situation (i.e., the student–teacher interaction occurred in the context of maze completion), rather than from independent situations (i.e., an academic task that does not include a social interaction and vice-versa). This overlap may have created confounding effects, making it difficult to adequately assess the self-protective hypothesis in the academic domain.

Despite the limitations of these studies (Diener and Milich 1997; Ohan and Johnston 2002), they offer insight into the mechanism that may be responsible for the PIB in children with ADHD. Upto date, the self-protective hypothesis has garnered more empirical support than any other explanation for the PIB in children with ADHD. Nonetheless, because inconsistencies (e.g., support is found in the social but not academic domain) and methodological limitations remain, additional investigation and extension to other domains of competence are warranted.

In sum, the function of the PIB in children with ADHD is unclear. Cognitive immaturity, neuropsychological deficits, ignorance of incompetence, and self-protection are possible explanations; however, as discussed, most of these hypotheses have not been directly tested. Further, these hypotheses may not be mutually exclusive. For example, cognitive immaturity and ignorance of incompetence may be difficult to distinguish; in fact, these two hypotheses may compliment each other. That is, because children with ADHD may be cognitively immature, they may also be deemed incompetent in a given domain. At this time, the self-protective hypothesis has accrued the most empirical support and appears to provide the most viable explanation for the PIB. Additional research is needed to confirm or disconfirm the other hypotheses and elucidate the function of the PIB in children with ADHD.

Effects of Sample Heterogeneity

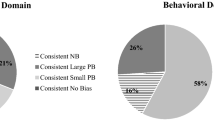

Given the high rates of comorbid mental health diagnoses experienced by children with ADHD (Barkley 1990; Jensen et al. 1997), as well as the multiple subtype classifications (American Psychiatric Association 2000), it is widely accepted that this population is highly heterogeneous. A recent review of comorbidity in ADHD estimates that between 43% and 93% of children with ADHD have comorbid disruptive behavior disorders and 13–51% have comorbid internalizing diagnoses (Jensen et al. 1997). These maladaptive, co-occurring symptoms may alter the expression of the PIB. Next, we discuss the effects of comorbid depressive symptoms, aggression, and low academic achievement, as well as ADHD subtype and gender on the PIB.

Comorbid Depressive Symptoms

Previous research indicates that symptoms of depression uniquely affect positive illusory self-perceptions in children with ADHD (Hoza et al. 2004, 2002). In general, the pattern of findings is consistent with the overall effects of depression within child and adolescent populations (e.g., Gladstone and Kaslow 1995). Namely, two studies have examined the role of comorbid depression by comparing the self-perception patterns among three groups of children: (a) children with ADHD and comorbid depressive symptoms (ADHD + Dep), (b) children with ADHD without depressive symptoms (ADHD − Dep) and (c) non-impaired control children. Interestingly, children with ADHD − Dep overestimated their competence relative to all criteria (i.e., parent and teacher ratings) significantly more than children with ADHD + Dep and non-impaired children (Hoza et al. 2004, 2002). Furthermore, children with ADHD + Dep did not significantly differ from similarly aged, non-diagnosed peers (i.e., children without ADHD or depressive symptoms) in estimations of self-competence relative to criterion (Hoza et al. 2004). In other words, comorbid depressive symptoms, as determined by elevated scores on the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovocas 1992), appear to mitigate the PIB in children with ADHD. Thus, symptoms of depression, even among children with ADHD, continue to be associated with more modest self-evaluations. Given that children with ADHD and comorbid depressive symptoms seem to exhibit a different self-perception pattern than other groups of children with ADHD, future studies should compare children with ADHD and comorbid depression to other populations, such as children with depressive symptoms but not ADHD.

Comorbid Aggression

Treuting and Hinshaw (2001) were among the first researchers to examine the effects of comorbid aggression on the absolute self-perception scores of children with ADHD (i.e., using an updated version of the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale [Piers, 1984]); however, their results have not been replicated. In this study, boys with ADHD and comorbid aggression demonstrated lower self-perceptions on four out of the seven subscales (behavioral, academic, happiness, and global self-concept) than did non-aggressive boys with ADHD. On the remaining three subscales, the two groups were statistically similar. However, these results must be interpreted with caution as there were high rates of depression in the sample of boys with ADHD and comorbid aggression. Consequently, depressive symptomatology, rather than aggression, may have been responsible for lower self-perception ratings among the aggressive subgroup of children with ADHD. Further, we note that this study examined absolute self-perceptions, rather than self-perceptions relative to a criterion. As such, it is possible that different pattern of results may have emerged if children’s self-perceptions were compared to a criterion.

Hoza et al. (2002) advanced our underststanding of the role of comorbid aggression by examining children’s self-perceptions relative to teacher ratings in boys with ADHD and comorbid aggression (ADHD + Agg), boys with ADHD without comorbid aggression (ADHD − Agg), and non-impaired boys. In contrast to Treuting and Hinshaw (2001), Hoza et al. (2002) results revealed that both ADHD subgroups overestimated their competence relative to teacher ratings in the scholastic, social, and behavioral domains significantly more than did control boys (Hoza et al. 2002). However, boys with ADHD + Agg overestimated their competence within the social and behavioral domains significantly more than did boys with ADHD − Agg. Social and behavioral competence are two areas that would likely be most affected by aggressive behavior. Interestingly, estimations of competence in other domains where aggression likely has little or no effect, such as physical appearance, were not affected by the presence of comorbid aggression. A similar pattern was found in a sample that included both boys and girls with ADHD, lending additional support to the findings (Hoza et al. 2004).

Comorbid Academic Difficulties

Interestingly, the role of comorbid academic difficulties is similar to that of comorbid aggression in that children with ADHD and academic difficulties tend to overestimate their competence the most in the domain in which they experience the greatest deficits (Hoza et al. 2004). Results from two studies suggest that children with ADHD and low academic achievement overestimated their academic competence as compared to a criterion significantly more than did children with ADHD who demonstrated average or above-average academic achievement (Hoza et al. 2004, 2002). However, children with ADHD and low academic achievement did not demonstrate such overestimation in domains in which they experienced less difficulty (e.g., athletic competence). Since this pattern has been found in other domains (i.e., aggression) and because low academic achievement is commonly found in children with ADHD (Hinshaw 1992), future research should continue to explore the role of low academic achievement on the presentation of the PIB.

ADHD Subtype

Not surprisingly, the three subtypes of ADHD (American Psychiatric Association 2000) are unique with regard to their clinical manifestations (Gaub and Carlson 1997). As such, Owens and Hoza (2003) explored the relation between ADHD subtype and the manifestation of the PIB. Owens and Hoza examined self-perceptions of scholastic competence in boys and girls with a combination of hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive (HICB) symptoms and boys and girls with inattentive (IA) symptoms using both teacher report and standardized achievement tests as criterion measures. Subtype differences emerged when examining both absolute self-perception scores from the SPPC (Harter 1985) and self-perceptions relative to a criterion score (e.g., teacher ratings, achievement scores). Children with HICB were more likely than children with IA to overestimate scholastic competence when using math and reading achievement scores as the comparison criterion. Moreover, in some cases, children with IA actually underestimated their scholastic competence relative to the criterion and did not display a PIB.

The findings of Owens and Hoza (2003) warrant replication as there have been no other studies examining the role of ADHD subtype differences in the PIB. Nonetheless, the preliminary results suggest that future studies examining the PIB should consider role of ADHD subtype before drawing conclusions about the ADHD sample as a whole. Furthermore, it is possible that the lower self-perceptions of competence in IA children occurred as a function of sluggish cognitive tempo, a characteristic that is present in some children with IA. Since children with IA who demonstrate a sluggish cognitive tempo tend to be more depressed and have poorer social skills than children with IA who have a more active cognitive tempo (Carlson and Mann 2002), the unique and combined contributions of sluggish cognitive tempo and depression in explaining ADHD subtype differences in the PIB warrant further exploration.

Gender

Given that ADHD is predominantly diagnosed in boys (American Psychiatric Association 2000), many of the initial studies investigating the PIB included only boys in their sample. To date, only three studies (Evangelista et al. 2007; Hoza et al. 2004; Owens and Hoza 2003) have investigated the PIB with a discrepancy analysis in both boys and girls with ADHD; and in general, the pattern suggests that the PIB is present in both sexes.

The only gender differences that were found in Hoza et al’s (2004) study were main effects of gender, and thus, not specific to children with ADHD. Namely, when teacher report was used as the criterion, boys (with and without ADHD) overestimated their behavioral competencies as compared to the criterion more than girls (with and without ADHD), whereas girls (with and without ADHD) underestimated their physical appearance as compared to the criterion more than boys (with and without ADHD; Hoza et al. 2004). Similarly, in Owens and Hoza’s (2003) study, significant main effects of gender were found, but significant gender × ADHD status interactions were not found. The gender effects indicated that girls overestimated their academic competence more than boys when judged against teacher report and math achievement scores (Owens and Hoza 2003). Given that far fewer girls than boys participated in these three studies—only 20% of the ADHD sample, combined across studies—the conclusions that can be drawn are limited. The best summary of extant data is that gender differences have not been found in the manifestation of the PIB in children with ADHD.

Limitations and Conclusions

To date, no studies have examined the moderating effect of ethnicity on the PIB within an ADHD sample. However, there are some indications that socio-cultural differences may exist. David and Kistner (2000) found that African-American children were more likely to report disproportionally higher self-ratings of peer likeability when compared to a criterion were than Caucasian children. However, ADHD symptoms were not assessed and comparisons were made based upon peer reports of aggressive behavior. Nevertheless, such indications of ethnic differences in self-perceptions warrant further investigations of race, culture, and socioeconomic status, and their relation to the PIB in children with ADHD. Similarly, little attention has been paid to the expression and manifestation of the PIB across the developmental spectrum. Indeed, most studies have restricted their samples to children between the ages of 8 and 12. Clearly, the role of development in the PIB warrants additional investigation through broad cross-sectional and longitudinal studies.

In summary, it is indisputable that the ADHD population includes significant heterogeneity. Collectively, past research indicates that children’s patterns of self-perceptions are associated with co-occurring symptoms and functional impairment. Comorbid difficulties may diminish (i.e., depressive symptoms) or exacerbate (i.e., aggression, low achievement) the degree to which the PIB is present. In addition, there is some evidence that hyperactive/impulsive symptoms may be more strongly correlated with the PIB than inattentive symptoms (Owens and Hoza 2003). However, replication of this finding is warranted. Future studies could advance the literature by comparing children with ADHD and comorbid symptoms to impaired, non-ADHD samples (e.g., children with learning disabilities, children with depression, children with aggression). Finally, while gender differences have not been found in the manifestation of the PIB in children with ADHD, continued investigation of gender is warranted until this null finding has been replicated across multiple studies.

In general, we cannot provide authoritative conclusions regarding the effect of sample heterogeneity on the PIB, as no one study has parceled out all potential comorbidities, ADHD subtypes, and genders to definitively quantify the effects of these characteristics on the PIB. Yet, as the respective studies indicate, comorbidity, ADHD subtype, and gender must all be considered in future studies in order to better elucidate the manifestation and function of the PIB. In addition, researchers investigating the impact of ethnicity or development will be breaking new ground in this area of research.

Implications and Future Directions

Taken together, past research supports the existence of inflated perceptions of self-competence in children with ADHD. However, the critical question is whether the PIB is adaptive or maladaptive in children with ADHD. There are conflicting views as to whether accurate self-perceptions are necessary to one’s healthy well being. Taylor and Brown (1988) suggested that moderate, but not excessive, positive illusions are advantageous in that they lead individuals to approach and persist when faced with a challenging task. Extant data do not provide an answer to this question for children with ADHD. Given the functional deficits associated with ADHD, a contextual factor that warrants consideration when investigating this question is the child’s actual competence. That is, children with ADHD who overestimate their competence, but perform within the average range, may indeed experience the advantages of positive illusions on task persistence. In contrast, it is possible that children with ADHD who overestimate their abilities and perform below average may experience these advantages in the short-term, but may actually experience negative consequences from the PIB over the long-term.

Interestingly, there is some preliminary evidence that excessively inflated positive illusions in children with ADHD may have a short-term buffering effect against depression (Vaughn 2007). It seems likely, however, that the short-term benefits of positive illusions may be outweighed by the negative long-term consequences of being unable to recognize and remediate functional deficits (for discussion, see Owens and Hoza 2003). For example, it has been suggested that awareness of one’s own deficits may serve a motivating function in behavioral treatment (Hoza and Pelham 1995), whereas inaccurate estimations of self may interfere with treatment progress. Further, some studies suggest that boys with externalizing behaviors who respond best to treatment are those with low self-esteem (Lochman et al. 1985) or low self-confidence (Hoza and Pelham 1995). This suggestive evidence implies that children with ADHD who demonstrate positive illusory self-perceptions of competence may not respond well to treatment, possibly resulting in more negative consequences in adolescence and adulthood. Nonetheless, to date, a longitudinal study examining the long-term benefits and consequences of the PIB in individuals with ADHD has yet to be conducted. Thus, such studies are warranted.

Some researchers have contemplated the extent to which excessive positive illusions could be reduced through “humility training” (Gresham et al. 1998, p. 405) in order to facilitate awareness and motivation for improvement. Gresham and colleagues (1998) suggested that children with ADHD who display a PIB might benefit from instruction with the goal of increasing awareness of their respective deficits. Although this conclusion is intuitively appealing, we note that this suggestion is both in direct contrast with conventional clinical wisdom (e.g., Bloomquist 1996) and also based on speculation rather than on empirical evidence. With the exception of Vaughn (2007), research examining the short-term or long-term benefits or consequences of the PIB on adjustment is lacking at this time. We strongly recommend additional research examining the relative adaptive or maladaptive consequences of positive illusory self-perceptions upon social-emotional functioning and task performance and persistence prior to altering current treatment approaches.

The current review also highlights the impact of sample characteristics on self-perception patterns in children with ADHD; this is of particular importance, given the heterogeneity of the ADHD population. Future studies should—at a minimum—include documentation of sample characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity, ADHD subtype, depressive symptoms, academic achievement, and aggression. Additional research further investigating the influence of each of these characteristics alone and in combination would offer additional contributions to extant literature. For example, until recently (e.g., Evangelista et al. 2007; Owens and Hoza 2003), studies investigating the PIB only included boys in their samples and those including girls still have a larger proportion of boys (e.g., Hoza et al. 2004; Owens and Hoza 2003). Similarly, to date, only one study has examined the role of ADHD subtypes in self-perceptions of academic competence (Owens and Hoza 2003).

As previously discussed, the self-protective hypothesis appears to be the explanation for the PIB with the most empirical support to date. Nonetheless, there are several limitations that can be improved upon. First, the self-protective hypothesis has not been examined in girls with ADHD. It is possible that boys and girls will respond differently in situations design to elicit possible self-protection. Second, the relation between ADHD subtype and the self-protective hypothesis has not been fully examined. Ohan and Johnston (2002) conducted some supplementary analyses to address this gap in the literature. For example they compared non-impaired boys to the subset of ADHD boys who met criteria for ADHD, Combined Type or ADHD, Hyperactive/Impulsive Type and the pattern of results did not change. However, the study lacked a sufficient number of ADHD, Inattentive Type children (and thus sufficient power) to adequately examine the relation between ADHD subtype and the self-protective hypothesis. Third, it seems necessary to further examine self-protection within the context of a more ecologically-valid academic task. It is possible that evidence for the self-protective hypothesis was not evident in Ohan and Johnston’s (2002) study, because child participants did not perceive the mazes to be representative of a typical academic task. On the other hand, it is possible that there are different explanations for positive illusions within different domains of competence. Future research examining these questions would be useful.

Treatment implications with regard to the PIB will differ markedly depending on the explanation that ultimately produces the most compelling support. Thus, it is crucial to further elucidate the function of the PIB, and to study the phenomenon longitudinally in order to adequately determine its possible short- and long-term benefits and consequences. Until such work is completed, it will be difficult to arrive at the most appropriate and effective treatment recommendations. Further, studies that directly compare two or more theoretical explanations within a given study would significantly advance our understanding of the relative merits of each theory in explaining the function of the PIB. Lastly, longitudinal and cross-sectional studies that span the developmental trajectory are warranted in order to definitively confirm or disconfirm the cognitive immaturity hypothesis as a valid explanation of the PIB in children with ADHD.

Given the methodological and statistical limitations of discrepancy analyses, future researchers are strongly encouraged to consider alternative strategies for evaluating the accuracy of children’s self-perceptions. Although we, like De Los Reyes and Kazdin (2004), suggest that future researchers be consistent in employing standardized discrepancy scores in examinations of self-perceptions relative to more objective criteria, we acknowledge that even this approach carries some limitations. We encourage future researchers to interpret findings in the context of the approach that they choose to employ, while acknowledging the limitations of that particular approach. Furthermore, given that different analytic strategies provide different types of information (e.g., absolute self-perception scores versus discrepancy scores), providing the results of both analyses may enhance our ability to draw conclusions across multiple studies. Finally, we hope that the development of new methodological approaches will remain a goal of future research in this area.

As noted earlier in this article, the PIB is not a phenomenon that is exclusive to children with ADHD. Indeed, past research has found positive illusions to be present in children who are peer-rejected and/or aggressive (Gresham et al. 1998; Hymel et al. 1993), and in children with learning disabilities (Heath and Glen 2005). Although these conditions often are comorbid with ADHD, the possibility arises that the PIB may occur as a function of general impairment—ADHD-related or otherwise. Consequently, we reiterate the need for future research to examine self-perceptions in similarly-aged and impaired non-ADHD populations in order to determine if the PIB is best accounted for by ADHD symptoms relative to other types of social, emotional, or behavioral deficits. For example, dimensional research examining associations between positive illusions and different types of dysfunction (e.g., ADHD symptoms, academic difficulties, peer relationship challenges) may be useful. Alternatively, studies that include other impaired comparison groups, such as children with other mental health disorders (e.g., depression) also may assist in determining whether the PIB is specific to ADHD or if it is a phenomenon related to more general difficulties or dysfunction. To conclusively assert that the PIB is truly a function of ADHD, future studies should include samples that better account for the heterogeneities that we have outlined and other disorders.

Despite significant functional problems in multiple domains, children with ADHD unexpectedly provide overly positive reports of their own competence in comparison to multiple different types of objective criteria. Furthermore, the degree to which these children overestimate their competence seems to differ from that found in the general population. This counterintuitive phenomenon has been the source of considerable controversy and discussion. This critical review has highlighted the important facets of extant research with the intent of providing guideposts for future studies that attempt to further elucidate the nature and function of the PIB in children with ADHD.

Notes

Treuting and Hinshaw (2001) also failed to find evidence of higher self-reported self-perceptions in children with ADHD as compared to controls. However, the pattern of findings in this study may be better explained through sample characteristics other than ADHD (i.e., depressive symptoms). Thus, Treuting and Hinshaw’s study is discussed in more detail later in the article (see Effects of Sample Heterogeneity section).

References

Alicke, M. D., & Govorun, O. (2005). The better-than-average effect. In M. D. Alicke, D. A. Dunning, &J. I. Krueger (Eds.), The self in social judgment (pp. 85–106). New York: Psychology Press.

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bagwell, C. L., Molina, B. S. G., Pelham, W. E. Jr., & Hoza, B. (2001). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: Predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1285–1292.

Barkley, R. A. (1990). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

Baumeister, R. F. (1989). The optimal margin of illusion. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 8, 176–189.

Bjorklund, D. F., & Green, B. L. (1992). The adaptive nature of cognitive immaturity. American Psychologist, 47, 46–54.

Bloomquist, M. L. (1996). Skills training for children with behavior disorders: A parent and therapist guidebook. New York: Guilford Press.

Cantwell, D. P., & Satterfield, J. H. (1978). The prevalence of academic underachievement in hyperactive children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 3, 168–171.

Carlson, C. L., & Mann, M. (2002). Sluggish cognitive tempo predicts a different patter of impairment in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive type. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 123–129.

Chi, T. C., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2002). Mother-child relationships of children with ADHD: The role of maternal depressive symptoms and depression-related distortions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 387–400.

Colvin, C. R., Block, J., & Funder, D. C. (1996). Psychometric truths in the absence of psychological meaning: A reply to Zuckerman & Knee. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1252–1255.

Cronbach, L. J. (1958). Proposals leading to analytic treatment of social perception scores. In R. Tagiuri &L. Petrullo (Eds.), Person perception and interpersonal behavior (pp. 353–379). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Cunningham, C. E., & Barkley, R. A. (1979). The interactions of normal and hyperactive children with their mothers in free play and structured tasks. Child Development, 50, 217–224.

Danforth, J. S., Barkley, R. A., & Stokes, T. F. (1991). Observation of parent-child interactions with hyperactive children: Research and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 703–727.

David, C. F., & Kistner, J. A. (2000). Do positive self-perceptions have a “dark side”? Examination of the link between perceptual bias and aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 327–337.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2004). Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychological Assessment, 16, 330–334.

Diener, M. B., & Milich, R. (1997). Effects of positive feedback on the social interactions of boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A test of the self-protective hypothesis. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 26, 256–265.

Duke, L. M., Seltzer, B., Seltzer, J. E., & Vasterling, J. J. (2002). Cognitive components of deficit awareness in alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology, 16, 359–369.

Dunning, D., Johnson, K., Ehrlinger, J., & Kruger, J. (2003). Why people fail to recognize their own incompetence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 83–87.

Edwards, J. R. (2001). Ten difference score myths. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 265–287.

Evangelista, N. M., Owens, J. S., Golden, C. M., & Pelham, W. E. (2007). The positive illusory bias: Do inflated self-perceptions in children with ADHD generalize to perceptions of others? Manuscript under review.

Gaub, M., & Carlson, C. L. (1997). Behavioral characteristics of DSM-IV ADHD subtypes in a school-based population. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 103–111.

Gladstone, T. R., & Kaslow, N. J. (1995). Depression and attributions in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 597–606.

Gresham, F. M., MacMillan, D. L., Bocian, K. M., Ward, S. L., & Forness, S. R. (1998). Comorbidity of hyperactivity-impulsivity-inattention and conduct problems: Risk factors in social, affective, and academic domains. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 393–406.

Griffin, D., Murray, S., & Gonzalez, R. (1999). Difference score correlations in relationship research: A conceptual primer. Personal Relationships, 6, 505–518.

Harter, S. (1981). A model of mastery motivation in children: Individual differences, developmental change. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), Aspects of the development of competence (pp. 215–255). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the self-perception profile for children. Denver: University of Denver Department of Developmental Psychology.

Heath, N., & Glen, T. (2005). Positive illusory bias and the self-protective hypothesis in children with learning disabilities. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 272–281.

Hinshaw, S. P. (1992). Academic underachievement, attention deficits, and aggression: Comorbidity and implications for intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 893–903.

Hodgens, J. B., Cole, J., & Boldizar, J. (2000). Peer-based differences among boys with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 443–452.

Horn, W. F., Wagner, A. E., & Ialongo, N. (1989). Sex differences in school-aged children with pervasive attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 17, 109–125.

Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Arnold, E. L., Pelham, W. E., Molina, B. S. G. et al. (2004). Self-perceptions of competence in children with ADHD and comparison children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 382–391.

Hoza, B., Mrug, S., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Bukowski, W. M., Gold, J. A. et al. (2005). What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with ADHD? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 411–423.

Hoza, B., & Pelham, W. E. (1995). Social-cognitive predictors of treatment response in children with ADHD. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14, 23–35.