Abstract

In recent years, there has been a growth in the number of evidence-based programmes designed to act directly on the factors that predispose or precipitate the onset of disorders or symptoms, rather than designing specific interventions to deal with each particular problem or disorder. The development of the Universal Strengthening Families Programme 11-14 (SFP 11-14) is one such example, where parents and adolescents are trained through the acquisition of strategic skills. The aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness of SFP 11-14 in tackling internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents from 11 to 14 years old. A quasi-experimental design was used with a control group, based on pre-test and post-test assessments and a follow-up. 289 adolescents and 353 parents took part, with 16 experimental groups and 17 control groups. From an analysis of variance and post-hoc Tukey-B tests, the effectiveness of SFP 11-14 in dealing with internalizing and externalizing symptoms was explored, confirming the efficacy of its short multicomponent (6-session) structure at the evaluation point (post-test1) and 6-month follow-up (post-test2). The results confirm that short preventive multicomponent programmes can prevent externalizing and internalizing symptoms in early adolescence. Improved family dynamics and relationships act as protective factors against possible mental disorders and against internalizing and externalizing symptoms. However, in future research, a specific assessment should be made of the effectiveness of each component in order to reinforce the more productive input, as well as conducting longitudinal evaluations so as to confirm long-term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms in Adolescents

In recent years, the appearance of externalizing and/or internalizing symptoms in adolescents has increased. At a worldwide level, it is estimated that approximately 13.4% of adolescents suffer from externalizing or internalizing symptomatology (Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, & Rohde, 2015), while the figure for Spain is 7.7% (Sánchez-García, Pérez, Paino, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2018). More specifically, externalization and internalization are linked to experiencing negative emotionality or inadequate emotional regulation (Aldao, Gee, De Los Reyes, & Seager, 2016; Eisenberg et al. 2005, 2009). They are two categories of mental disorders, with externalizing symptoms being associated with behavioural problems and internalizing ones with cognitive or internal processes (Eaton, Rodriguez-Seijas, Carragher, & Krueger, 2015). The problem is that, tied in with these symptoms, there is a high comorbidity between different mental disorders (Drabick & Kendall, 2010; Fanti & Henrich, 2010; Hektner, August, Bloomquist, Lee, & Klimes-Dougan, 2014; Perrino et al., 2014, 2016). Internalization would explain the comorbidity between some mood or anxiety-type disorders, while externalization would imply comorbidity between disorders associated with behaviour, impulsivity, or substance use (Colder et al., 2013; Eaton et al., 2015; Krueger & Eaton, 2015).

Cosgrove et al. (2011) ascribe the co-occurrence of symptoms to two types of factors: (1) personal variables and (2) family influence. In the case of personal variables, externalization problems seem to be associated with traits like impulsivity, negative emotionality and a lack of control or absence of sustained effort (Eisenberg et al., 2005, 2009), in addition to a tendency to experience anger (Karreman, de Haas, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković 2010). Meanwhile, internalization problems are associated with low impulsivity and a tendency toward sadness and anger (Eisenberg et al., 2009), as well as frequent feelings of fear (Karreman et al., 2010).

On the other hand, relevant literature supports the clear influence of paternal and maternal behaviour on both externalizing and internalizing symptoms (Baumrind, 1971; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Compas et al., 2017; García, Cerezo, de la Torre, Carpio, & Casanova, 2011; Hektner, August, Bloomquist, Lee, & Klimes-Dougan, 2014; Perrino et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2009). Williams et al. (2009) point out that authoritarian parenting styles increase externalizing behaviours in preschool children, and that they can cause antisocial or disruptive behaviours in adolescents. High rates of impulsivity at the age of 5 herald further externalizing problems at the age of 17 if accompanied by severe discipline from parents (Leve, Kim & Pears 2005). Similarly, it should be noted that overly permissive parenting will also have negative effects on externalizing symptoms in children (Hawkins et al., 2009; Negreiros, 2013), and it will get even worse if this inappropriate discipline is combined with no or just a low affective relationship (Baumrind, 1971; García et al., 2011; Torío et al., 2008; Vermeulen-Smit et al., 2015). In fact, García et al. (2011) point to parental rejection as being the highest predictor of internalization and externalization, supported by the findings of the said authors' study, which highlights how parental rejection, over control, and a lack of control foster internalization in the case of boys, while parental rejection and over control foster internalization in girls (García et al., 2011). León-del-Barco, Mendo-Lázaro, Polo-del-Río, & López-Ramos (2019) coincide in pointing to over control by parents as being a predictive variable that can boost internalizing symptoms by up to 6 times and externalizing symptoms by up to 4.8.

Another key factor is parent–child communication, which includes listening and empathic and assertive communication. A study by Balan, Dobrean, Roman, & Balazsi, (2017) identified emotional suppression by parents in relations with their children as being a predictive variable for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms. This is especially relevant during early adolescence, when the multiple changes that adolescents face can imply an increased risk of disorders, leading, in turn, to greater negative affectivity and emotional reactivity (Balan et al., 2016; Lacasa, Mitjavila, Ochoa, & Balluerka, 2015; Lochman & Wells, 2002). In fact, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2018), it estimated that approximately 1 in 7 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 have suffered from Major Depressive Disorder during the past year. Once the disorder takes hold, there is a significant deterioration in different areas (personal, social, educational, etc.), and interventions will be needed involving the deployment of time and resources that are not always available. Given the repercussions of the onset of a disorder, prevention is a key intervention strategy when the first signs of internalizing or externalizing symptoms appear so as to halt the process (Connell & Dishion 2008; Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003; Perrino et al., 2016; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008). More specifically, evidence-based programmes (EBP) are seen as being particularly suitable, since they act on the predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors of internalizing and externalizing symptoms through family training (Eaton et al., 2015; Fosco et al., 2013; Kumpfer et al., 2013; Van Ryzin et al., 2012; Vermeulen-Smit, Verdurmen, & Engels, 2014).

A Short-Term Prevention Programme: The Universal Strengthening Families Programme 11-14

The Strengthening Families Programme (SFP) was developed in line with the previous premises. Multiple empirical evidence has been built up on the effectiveness of both the original version and its Spanish validation, the Programa de Competencia Familiar or PCF according to its Spanish acronym (Ballester et al., 2018; Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003; Kumpfer & DeMarsh, 1985; Kumpfer, Fenollar, & Jubani, 2013; Orte et al., 2013; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2019). In this study, the version aimed at universal populations is presented, the Strengthening Families Programme 11-14 (SFP 11-4). Universal populations are characterized by the fact that they do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder, although members may suffer from internalizing or externalizing symptoms (Spoth, Guyll, & Shin, 2006; Spoth, Shin, Guyll, Redmond, & Azevedo,2009). The purpose of preventive programmes is to reduce externalizing or internalizing symptoms or to prevent new ones that may lead to the development of mental disorders. In fact, it has been confirmed that externalizing behaviour can turn into internalizing problems in late adolescence (Connell & Dishion 2008; Hektner, et al., 2014; Kjeldsen et al., 2016; Leve et al., 2005; Perrino et al., 2016). Similarly, comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms herald worse development in young people than any of the previous symptoms alone (Perrino et al., 2016).

SFP 11-14 intervenes by influencing two types of variables: (a) family variables; that is, inappropriate parental upbringing models and family dynamics, and (b) personal variables. SFP 11-14 has already demonstrated its effectiveness in improving family variables, family dynamics (increased resilience and less family conflict), and parenting styles (increased family involvement and positive parenting) (Sánchez-Prieto et al.,2019). SFP 11-14 is structured according to different types of skills, following the recommendations of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008). This adolescent-targeted programme focuses particularly on the following skills: (a) emotional regulation strategies, (b) communication skills and (c) coping skills. As for the parents, they are trained by working on the following strategies: (a) emotional regulation strategies, (b) communication skills, and (c) behavioural strategies to modify behaviour (see Table 1). The skills are reinforced at sessions for the family, and training at home is encouraged. The programme is based on 6 sessions, working in parallel groups with the children and parents, as well as the family as a whole. One recall session is held 6 months after the programme’s completion.

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of SFP 11-14 on reducing internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. More specifically, the aim was to analyse whether by working on parent and adolescent skills that can be incorporated into family dynamics, it is possible to reduce internalizing and externalizing symptoms that would lead to other disorders (see Table 2). The main contribution of the study is that the Spanish adaptation, SFP 11-14, attempts to reduce the symptoms through a short-term format of the programme (only 6 sessions). So far, only the study by Errasti et al. (2009) has implemented the universal version of the SFP in Spain, although the results could not be generalized due to the small sample size. In addition, its main objective was not the prevention of symptoms, but the prevention of substance use.

Methodology

Participants

SFP 11-14 was aimed at adolescents aged between 11 and 14, coinciding with the transition from primary to secondary school. The selection criteria for the participants were based on the principles of universal prevention. All the families showing an interest in taking part and meeting the inclusion criteria were accepted as participants (see Table 2). One of the inclusion criteria was the families’ attendance of 80% of the sessions.

The schools’ participation was based on three inclusion criteria: 1) They had to be schools in the Balearic Islands or Castilla y León region (places with trained professionals); 2) They were state schools or state-subsidized schools; and 3) They had not taken part in prevention programmes during the previous two years.

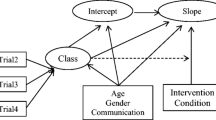

SFP 11-14 started with 353 participants, with 16 experimental groups and 17 control groups. In total, 275 families and 289 adolescents took part in it. More specifically, the experimental group was made up of 175 adolescents, with a mean age of M = 11.49 (SD = 1.209). As for the parents, more mothers took part (N = 144), with just 54 fathers. The groups of adolescents were balanced in terms of gender (59.2% boys versus 40.8% girls). As for their stage in the education system, 78.2% were from the last cycle of primary education (the 5th and 6th years). A nuclear structure predominated among the families, characterized by a mother and father and their respective children (84.5%). Most of the sample lived in urban centres (73.5%) (see Table 3). The control group had fewer adolescents (N = 1 14) than the experimental group, although they were of similar mean ages (M = 12.15; SD = 1.152). There were also far fewer fathers (N = 19) than mothers (N = 88), with a mean age of M = 43.49 (SD = 5.903) for the mothers and M = 46.65 (SD = 7.228) for the fathers. There were an equivalent number of adolescents in both educational cycles (55.27 versus 44.73).

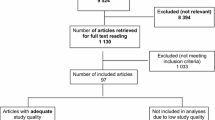

The adherence levels were high and they remained consistent. Of the 275 initial families, 90.55% continued through to the end (249 families). The adherence rate for the adolescents was similar (90.66%), while for the parents it was somewhat lower (86.40%). A total of 165 families started SFP 11-14 in the experimental group, with an adherence rate of 93.33%. The corresponding rate for families in the control group was 86.35% (see Fig. 1). The adolescents from primary schools in the experimental group had the highest retention rates (95.69%). The highest losses in the sample were among the parents of children from secondary schools in the control group (21.82%).

Design and Procedure

A quasi-experimental design was used, with a control group (Ballester et al., 2014), pre-test and double post-test. The schools taking part in the experimental or control group were randomly assigned.

The schools were contacted and the programme was explained to the management team. All interested families meeting the SFP 11-14 inclusion criteria were summoned and recruited. They were not offered any incentives to take part. The trainers who gave the programme had received prior training ((Ballester et al., 2018; Pascual et al., 2019). The implementation consisted of parallel sessions for the parents and children, and a subsequent family session to reinforce the input with the whole family (Pascual et al., 2020). Assessments were made prior to the first session (pre-test), on completion of session 6 (post-test 1) and 6 months after the end of SFP 11-14 (post-test 2). The post-test evaluation was given to all the participants who had completed the programme. Self-reports were used as the assessment tool for the parents and children, filled out in different rooms to prevent them from influencing one another. The fidelity of the sessions and the participants' progress were evaluated through self-reports and evaluations by independent observers at each session. The trainers were responsible for how the input was given, and they were evaluated through self-reports and by the parents and children through a satisfaction questionnaire.

Information about SFP 11-14 was given to the members of the control group, and their future participation as part of the experimental group was suggested before the start of the programme. They were then put on a waiting list to take part in future applications.

An ethical protocol was established to guarantee the participants’ confidentiality. The protocol was approved by the Spanish Ministry for the Economy & Competitiveness (MINECO according to its Spanish acronym). Likewise, the University of the Balearic Islands’ Ethical Committee made sure that SFP 11-14 observed ethical criteria. Lastly, the families had to sign a consent form that guaranteed confidentiality.

Measures

The analysis was conducted using the Behavioural Assessment System for Children and Adolescents (BASC), which is correlated with the diagnostic criteria of several DSM-IV diagnostic categories (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The validation for the Spanish population and version 3 (BASC-3) for adolescents aged from 12 to 18 were used (González, Fernández, Pérez, & Santamaría,, 2004). Although some children were 11 years old, the questionnaire that best fit in with their developmental stage was version 3.

Parent Rating Scales (PRS)

The PRS were based on 68 items. They reported 7 clinical scales with a high internal consistency: (1) aggressiveness (α = 0.829), (2) hyperactivity (α = 0.809), (3) attention problems (α = 0.724), (4) atypicality (α = 0.694), (5) depression (α = 0.844), (6) anxiety (α = 0.653) and (7) somatization (α = 0.866). The whole internalizing problems scale, with an α = 0.873, was used, made up of the depression, anxiety and somatization scales. The Behavioural Symptoms Index (BSI) was also analysed where high scores could indicate externalizing symptoms. The BSI, with an α = 0.912, is made up of the aggression, hyperactivity, attention problems, atypicality, anxiety and depression scales. The items assessed components on a Likert scale, with the following four possible answers: (1) Never; (2) Sometimes; (3) Often and (4) Almost always. The self-report which could be answered in about 15 min.

Self-Report of Personality (SRP)

The PRS reported 8 personal scales with a high internal consistency: (1) social stress (α = 0.793), (2) anxiety (α = 0.868), (3) depression (α = 0.747), (4) inadequacy (α = 0.793), (5) interpersonal relations (α = 0.744), (6) relations with parents (α = 0.716), (7) self-esteem (α = 0.836) and (8) self-reliance (α = 0.797). The whole personal adjustment scale was obtained by combining the interpersonal relations, relations with parents, self-reliance and self-esteem scales. The Emotional Symptoms Index (ESI), with a consistency of α = 0.865, was also obtained, based on the anxiety, depression, interpersonal relations, self-esteem, social stress and sense of inadequacy scales (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). In the self-report, the items were answered on a dichotomous scale, choosing from the following options: (1) True or (2) False. The self-report which could be answered in about 30 min.

As for the self-report’s psychometric properties, the scales system has a mean confidence interval ranging from 0.70 for the parents to between 0.67, 077 and 0.80 for the adolescents. The different types of scales provide an adequate consistency. The results of the test–retest reliability show very high correlations of 0.85 for the parents, with mean values of 0.89 for the children. The Spanish validation of the Family Competence Programme obtained very similar values to previous US studies (González et al., 2004).

Analysis Strategy

The data analysis focuses on the results of the factors and scales taken into consideration for each of the instruments, in accordance with the research hypotheses. The analysis was conducted using SPSS 25. To achieve the proposed objectives and test the hypotheses, the analysis was divided into three parts: a. An analysis of the response to the programme by the families and education centres, b. An analysis of compliance with the programme recommendations in the short and mid term (6 months), and c. Hypothesis testing, conducting a study of the dependent variables, according to key independent variables. For point c, the following analyses were conducted:

-

1.

A descriptive analysis of each of the scales under consideration, in accordance with the established protocols for the corresponding instrument (the assignment of ratings, scales, etc.), for each of the subjects, establishing group results.

-

2.

An analysis of differences of means (t-test, intragroup and intergroups), comparing differences (pre/post and between the experimental and control group through ANOVA analysis of variance tests, with post hoc tests (Tukey- b)). The sequence used in the analysis was reproduced at each of the data collection stages (post-test). Changes in the groups were identified by comparing the pre-test and post-test measurements (at the end of the application) for each of the dimensions, studying various concurrent factors.

Results

Parental Evaluation Using the Parent Rating Scales

Internalization

There was a significant drop (F (2, 548) = 5.991, p < .01) in the case of the anxiety scale. This was recorded immediately after the application of SFP 11-14 (post-test1; q = 46.96), with stable effects 6 months later (post-test2; q = 46.21).

A big drop in the somatization scale could also be observed at post-test1 (q = 46.63) following the application of SFP 11-14, with stable effects at the post-test2 stage (q = 46.13). The analysis of variance gave statistically significant results (F (2, 547) = 5.320, p < .01). The scores of the depression scale dropped significantly (p < .01), albeit 6 months after the application of SFP 11-14 (pre-test; q = 51.94 versus post-test2; q = 48.39) (see Tables 4 and 5).

Externalization

As for the externalizing symptoms, the parents reported a significant drop in the attention problems scale (F (2, 548) = 4.231, p < .01). This improvement occurred on completion of SFP 11-14 (post-test1; q = 52.45) and it remained constant at the follow-up stage (post-ttest2; q = 49.69). In contrast, no significant changes were found in the atypicality scale (p = 0.557).

The ANOVA score for the aggression scale was (F (2, 548) = 5.214, which was statistically significant (p < .01) (see Table 4). However, the post-hoc comparison with Tukey B showed that the reduction in aggression occurred 6 months after SFP 11-14 (q = 47.46) (see Table 5). A similar effect, albeit at a more moderate statistical level, occurred with the hyperactivity scale, with a value of (F (2, 547) = 3.894, p < 0.05). A decrease in hyperactivity levels was identified at the post-test2 stage (q = 51.02), when compared with the initial evaluation (q = 54.52).

Global Scales

The globalinternalizing problems scale revealed a notable improvement in the adolescents on completion of SFP 11-4 (F (2, 547) = 7.151, with a high statistical significance (p < .001). It showed that outcomes were achieved after the programme’s application (the pre-test was q = 51.09 while the post-test1 was q = 47.50) and that they were maintained at the post-test2 stage (q = 46.65).

The comparison of means in the behavioural symptoms index was statistically significant (p < 0.05). In the post-hoc test, no differences were found between the pre-test and post-test1 stages. An evaluation at the post-test2 stage was not possible due to the reduction in the size of the sample.

The Adolescents’ Self-Report of Personality

Internalization

The results of the sense of inadequacy scale were very significant (F (2, 429) = 6.683, p < .001). After the application of SFP 11-14 (post-test1; q = 47.39), some differences in relation to the pre-test could be observed (q = 50.43), which were further consolidated at the follow-up stage (q = 46.90). As for self-esteem, there was a significant improvement (F (2, 432) = 3.559, p < .05) at the follow-up stage (q = 52.47).

Unlike the improvements achieved in the parental scale, in the case of the adolescents, although differences were found between the groups in the anxiety scale (PT; PTT2 > PTT2), they were not significant (p = .062). Changes were reported for the depression scale (F (2, 430) = 3.556), but although the variations were significant (p < .05), the results of the group comparison were ambiguous and no decrease in symptoms of depression could be attributed to SFP 11-14. No significant changes were obtained (p = .263) in the self-reliance scale.

Externalization

In the case of the social stress scale, a notably significant ANOVA of F (2, 431) = 5.149, p < .01) was obtained. The adolescents improved at the follow-up stage (q = 45.48) compared with the pre-test (q = 49.25) (see Tables 6 and 7).

The adolescents also reported an improvement in their relations with their parents after completing SFP 11-14 (F (2, 433) = 3.046, p < .05), although the variations were ambiguous and no differences could be established in the different evaluations (PT; PTT1; PTT2). No significant results were found for the interpersonal relations scale (p = 0.642).

Global Scales

In the Emotional Symptoms Index, a noteworthy improvement was observed after the application of SFP 11-14 (a value of q = 46.07 was achieved at the post-test1 stage, unlike the pre-test, which had higher values (q = 48.87)). A statistically significant F (2, 425) = 5.903, p < .01) was obtained. The results were maintained at the follow-up stage (post-test2; q = 44.98). The analysis of variance of the global personal adjustment scale was not significant (p = .062).

Discussion

In recent years, growing evidence-based practice has started to advocate direct intervention on a set of precipitating and predisposing symptomological factors due to the high comorbidity of many disorders (Hektner et al., 2014; Hentges et al., 2020; Martinsen et al., 2019; Musiat et al., 2014; Perrino et al., 2016). Multicomponent programmes have come to replace action targeted at individual problems, in keeping with the transdiagnostic model (Johnson et al., 2016; Kranzler et al., 2016; Krueger & Eaton, 2015). This is the case of SFP 11-4, which is designed to prevent or to reduce the onset of symptoms and differing problems by strengthening parenting techniques and adolescent skills.

The obtained results confirm the effectiveness of SFP 11-4 in dealing with internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. In the former’s case, the parents reported reductions associated with the anxiety, somatization and depression scales. The three scales make up the global internalizing scale, where improvements were also achieved. The adolescents reported an increase in the self-esteem scale and a drop in the sense of inadequacy scale. A reduction in the Emotional Symptoms Index was also recorded, made up of the anxiety, depression, interpersonal relations, self-esteem, social stress and sense of inadequacy scales. As for externalizing symptoms, the parents reported improvements in the attention problems, aggression and hyperactivity scales. In contrast with this, the adolescents only regarded a reduction to have occurred in symptoms relating to the social stress scale.

Through its components, SFP 11-14 was therefore effective in dealing with internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents and in family dynamics and family relations (Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2019). The selected components were: a) emotional regulation strategies, b) communication skills, c) coping skills, and d) behavioural modification strategies. The current incorporation of emotional regulation strategies in prevention programmes has been highlighted by numerous authors as playing a key role in the control and prevention of internalizing and externalizing symptoms due to the association between them (Compas et al., 2017; Eisenberg et al. 2009; Hentges et al., 2020; Kranzler et al. 2016; Johnson et al. 2016; Martinsen et al., 2019; Musiat et al., 2014). Emotional dsyregulation can be caused by a lack of activation, inadequate strategies or the use of dysfunctional strategies, and so the intervention must help to work on these (Aldao et al. 2016; Hervás, 2011). More parental self-control could reduce externalizing behaviour in children (Havighurst et al., 2015), and so SFP 11-14 also focuses on parental emotional regulation skills.

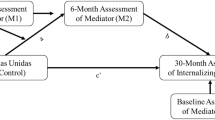

At the same time, parent–child communication skills are a fundamental tool in improving family interaction (Botvin et al., 2003). Perrino et al. (2014; 2016) highlight the reduction in externalizing symptoms at the 18-month follow-up stage and in internalizing symptoms at 30 months. In SFP 11-14, the participants experienced a reduction in levels of social stress (defined as the level of stress experienced in social interactions) and in family conflicts and there was an improvement in family engagement (Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2019). The aforementioned skills were complemented by coping skills, aimed at boosting the children’s capacity to withstand peer group pressure. They are skills that have proven to be effective in preventing disorders related to substance use and risk behaviours (Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003; Kumpfer et al., 2013). As for behavioural modification strategies, the purpose of these was explained to the parents in order to consolidate adequate use of discipline. Clear rules and coherent discipline will act as protective factors (Negreiros, 2013; Torío et al., 2008; VermeulenFP.

Interventions at an early stage of adolescence can influence the transition to secondary education. This period can involve numerous different challenges for adolescents (possible risk factors) in addition to greater personal autonomy and independence from their parents and the perception of more peer group pressure (Hentges et al., 2020; Lochman & Wells, 2002; Van Ryzin, Stormshak, & Dishion, 2012).

A relevant aspect of the results was that, in some scales, the improvements occurred after 6 sessions of the application of SFP 11-4. Although in the case of the anxiety, somatization, attention problems and sense of inadequacy scales, significant changes occurred on completion of SFP 11-4, with the depression, aggression, hyperactivity, self-esteem and social stress scales, these improvements were not identified until the evaluation at the refresher session (post-test2). A reason may be because SFP 11-4 is a short 6-session programme, with one refresher session. Due to its brief design, emphasis is placed on practicing the skills and strategies at home. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, at “family session 1”, the need for all the family to practice the skills was highlighted. The acquisition and implementation of these day-to-day habits and routines help to bring about more noteworthy mid-term improvements (Barlow, Smailagic, Ferriter, Bennett, & Jones, 2010; Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003).

In short, the literature on prevention programmes and the outcomes of this study both demonstrate that protective factors can be boosted by certain types of family dynamics and child-rearing styles, helping to prevent the onset of symptoms or disorders in children. This makes family interventions a priority (Kumpfer, et al. 2013; Fosco, Frank, Stormshak, & Dishion 2013; Spoth et al., 2009; Stormshak et al., 2011; Van Ryzin et al., 2012).

Limitations

Effective outcomes were not achieved in the case of some variables, particularly those assessed by the adolescents (interpersonal relations, relations with parents, self-reliance, personal adjustment). On the other hand, improvements were obtained at the end of the programme and at the 6-month follow-up. Nonetheless, a long-term longitudinal study would be useful in comparing or confirming whether the improvements were maintained, as recommended in the relevant literature, which states that certain important changes in internalizing problems occur at later ages, hence calling for long-term monitoring of the participants (Hektner, et al., 2014; Perrino et al., 2016). On the other hand, it should be taken into account that, although the schools were randomized in accordance with experimental conditions, this randomization was not carried out for the families. This could weaken the study's internal validity. In future research into the SFP, the randomization of the families should be guaranteed in order to achieve the required experimental design.

Despite the outlined improvements, children with elevated symptoms prior to commencing the programme should be transferred to selective or indicated prevention programmes so as to ensure a more carefully tailored, focused intervention and a more exhaustive analysis of factors with a precipitating or predisposing effect.

Implications and Directions for Future Research

This study highlights three strengths of SFP 11-4. Firstly, it does not solely focus on one type of skill. Instead, it works on the development of a series of efficient strategies with a cumulative effect. Secondly, it demonstrates significant changes in adolescents through a short-format programme. Until now, empirical evidence on family dynamics and adolescent clinical symptoms had been built up from the selective version of the Strengthening Families Program (14 sessions) (Ballester et al., 2018; Orte et al., 2015, 2016). However, with SFP 11-4, it can be seen that from a short, highly structured design with sessions focused on key components, significant changes can also be achieved in internalizing and externalizing factors in adolescents. It is important to bear in mind that, in universal populations, the onset of symptoms or disorders is less likely. As a result, when universal programmes are compared with others targeted at individuals with elevated symptoms, important changes are hard to achieve (Johnson et la., 2016; Spoth et al., 2009). Lastly, the results of the follow-up show that the outcomes are maintained in the mid-term and that new significant changes will no doubt emerge, probably associated with ongoing practice with the strategies and skills, incorporating them in routines and behaviour patterns (Barlow et al., 2010).

As for future research, from the evaluations, an analysis must be made of the effectiveness of each individual component on the final outcomes. This would ensure a fuller vision of the importance of each transmitted skill so that the programme could be reformulated to achieve higher levels of efficiency and effectiveness. More specifically, through an exhaustive evaluation of emotional regulation, it would be possible to confirm or reject the correlation between emotional regulation and externalizing and internalizing symptoms in prevention programmes.

Conclusions

In its universal version, SFP 11-4 has been shown to be effective in reducing and preventing externalizing and internalizing symptoms in adolescents aged between 11 and 14. After applying the 6 sessions of the programme, effective outcomes were identified through reduced anxiety, somatization, attention problems, and feelings of incapacity, in addition to improvements in the internalizing problems scale and the Emotional Symptoms Index. Six months after the application, in the longitudinal evaluation, improvements were also identified in depression, aggression, hyperactivity, self-esteem and social stress. It is shown that, through a short multicomponent programme, it is possible to train parents and adolescents, improving relationships and family dynamics (Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2019). These improvements have been demonstrated to act as a protective factor against the onset of possible mental disorders or new externalizing or internalizing symptoms.

References

Aldao, A., Gee, D. G., De Los Reyes, A., & Seager, I. (2016). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in the development of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: Current and future directions. Development and psychopathology, 28(4), 927946. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000638.

Balan, R., Dobrean, A., Roman, G. D., & Balazsi, R. (2017). Indirect effects of parenting practices on internalizing problems among adolescents: The role of expressive suppression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0532-4.

Ballester, L., Nadal, A., & Amer, J. (2014). Métodos y técnicas de investigación educativa/Educational research methods and techniques. Palma: Edicions UIB.

Ballester, Ll., Orte, C., Gomila, M.A., Pozo, R., Quesada, V., Fernández, M., ... & López, C. (2018). El “Programa de Competencia Familiar” en España; evaluación longitudinal/The Family Competence Program" in Spain; longitudinal evaluation".En (Ed.) Orte, C. & Ballester, Ll., En Intervenciones eficaces en prevención familiar en drogas. Madrid: Octaedro.

Barlow, J., Smailagic, N., Ferriter, M., Bennett, C., & Jones, H. (2010). Group-based parent-training programmes for improving emotional and behavioural adjustment in children from birth to three years old. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003680.pub2.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Currents patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4, 1–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030372.

Botvin, G. J., Griffin, K. W., Paul, E., & Macaulay, A. P. (2003). Preventing tobacco and alcohol use among elementary school students through life skills training. Journal of Child and Adolescent Subtance Abuse, 12(4), 1–17.

Colder, C. R., Scalco, M., Trucco, E. M., Read, J. P., Lengua, L. J., Wieczorek, W. F., et al. (2013). Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(4), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0.

Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., ... & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 939.

Connell, A. M., & Dishion, T. J. (2008). Reducing depression among at- risk early adolescents: three year effects of a family-centered intervention embedded within schools. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 574–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.574.

Cosgrove, V. E., Rhee, S. H., Gelhorn, H. L., Boeldt, D., Corley, R. C., Ehringer, M. A., ... & Hewitt, J. K. (2011). Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 39(1), 109-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496.

Drabick, D. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Developmental psychopathology and the diagnosis of mental health problems among youth. Clinical Psychology, 17, 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01219.x.

Eaton, N. R., Rodriguez-Seijas, C., Carragher, N., & Krueger, R. F. (2015). Transdiagnostic factors of psychopathology and substance use disorders: A review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-1001-2.

Eisenberg, N., Sadovsky, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Losoya, S. H., Valiente, C., ... & Shepard, S. A. (2005). The relations of problem behaviour status to children's negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology, 41(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0

Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., Spinrad, T. L., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., ... & Losoya, S. H. (2009). Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behaviour problems. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 988. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016213

Errasti, P. J. M., Al-Halabi-Díaz, S., Secades, V. R., Fernández-Hermida, J. R., Carballo, J. L., & García-Rodríguez, O. (2009). Prevención familiar del consumo de drogas: el programa «Familias que funcionan». Psicothema, 21, 45–50.

Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2010). Trajectories of pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems from age 2 to age 12: Findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020659.

Fosco, G. M., Frank, J. L., Stormshak, E. A., & Dishion, T. J. (2013). Opening the “Black Box”: Family Check-Up intervention effects on self-regulation that prevents growth in problem behaviour and substance use. Journal of School Psychology, 51(4), 455–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.02.001.

García, M. C., Cerezo, M. T., de la Torre, M. J., Carpio, M. V., & Casanova, P. F. (2011). Prácticas educativas paternas y problemas internalizantes y externalizantes en adolescentes españoles/Parental educational practices and internalizing and externalizing problems in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema, 23(4), 654–659.

González, J., Fernández, S., Pérez, E., & Santamaría, P. (2004). Adaptación española del sistema de evaluación de la conducta en niños y adolescentes/Spanish adaptation of the behaviour assessment system in children and adolescents: BASC. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Havighurst, S. S., Kehoe, C. E., & Harley, A. E. (2015). Tuning in to teens: Improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalizing behaviour problems. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005.

Hawkins, J. D., Oesterle, S., Brown, E. C., Arthur, M. W., Abbott, R. D., Fagan, A. A., et al. (2009). Results of a type 2 translational research trial to prevent adolescent drug use and delinquency: A test of Communities That Care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 163(9), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.141.

Hektner, J. M., August, G. J., Bloomquist, M. L., Lee, S., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2014). A 10-year randomized controlled trial of the Early Risers conduct problems preventive intervention: Effects on externalizing and internalizing in late high school. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 355. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035678.

Hentges, R., Weaver Krug, C., Shaw, D., Wilson, M., Dishion, T., & Lemery-Chalfant, K. (2020). The long-term indirect effect of the early Family Check-Up intervention on adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms via inhibitory control. Development and Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419001482.

Hervás, G. (2011). Psicopatología de la regulación emocional: El papel de los déficit emocionales en los trastornos clínicos. Psicología conductual, 19(2), 347.

Johnson, C., Burke, C., Brinkman, S., & Wade, T. (2016). Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness program for transdiagnostic prevention in young adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 81, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.03.002.

Karreman, A., de Haas, S., van Tuijl, C., van Aken, M. A., & Deković, M. (2010). Relations among temperament, parenting and problem behaviour in young children. Infant Behaviour and Development, 33(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.008.

Kjeldsen, A., Nilsen, W., Gustavson, K., Skipstein, A., Melkevik, O., & Karevold, E. B. (2016). Predicting well-being and internalizing symptoms in late adolescence from trajectories of externalizing behaviour starting in infancy. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12252.

Kranzler, A., Young, J. F., Hankin, B. L., Abela, J. R., Elias, M. J., & Selby, E. A. (2016). Emotional awareness: A transdiagnostic predictor of depression and anxiety for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(3), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.987379.

Krueger, R. F., & Eaton, N. R. (2015). Transdiagnostic factors of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 14(1), 27–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20175.

Kumpfer, K. L., & Alvarado, R. (2003). Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviours. American Psychologist, 58(6–7), 457–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457.

Kumpfer, K. L., & DeMarsh, J. (1985). Genetic and family environmental influences on children of drug abusers. Journal of Children in Contemporary Society, 3–4, 49–91.

Kumpfer, K. L., Fenollar, J., & Jubani, C. (2013). Una intervención eficaz basada en las habilidades familiares para la prevención de problemas de salud en hijos de padres adictos a alcohol y drogas/An effective intervention based on family skills for the prevention of health problems in children of parents addicted to alcohol and drugs. Pedagogia Social Revista Interuniversitaria, 21, 85–108.

Lacasa, F., Mitjavila, M., Ochoa, S., & Balluerka, N. (2015). The relationship between attachment styles and internalizing or externalizing symptoms in clinical and nonclinical adolescents. Anales De Psicología, 31(2), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.2.169711.

León-del-Barco, B., Mendo-Lázaro, S., Polo-del-Río, M. I., & López-Ramos, V. M. (2019). Parental psychological control and emotional and behavioural disorders among Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030507.

Leve, L. D., Kim, H. K., & Pears, K. C. (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(5), 505–520.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2002). The Coping Power program at the middle-school transition: Universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, 16(4S), S40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.16.4S.S40.

Martinsen, K. D., Rasmussen, L. M. P., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Holen, S., Sund, A. M., Løvaas, M. E. S., ... & Neumer, S. P. (2019). Prevention of anxiety and depression in school children: Effectiveness of the transdiagnostic EMOTION program. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 87(2), 212.

Musiat, P., Conrod, P., Treasure, J., Tylee, A., Williams, C., & Schmidt, U. (2014). Targeted prevention of common mental health disorders in university students: randomised controlled trial of a transdiagnostic trait-focused web-based intervention. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e93621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093621.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administratio. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioural Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Negreiros, J. (2013). Participación parental en intervenciones familiares preventivas de toxicodependencias: Una revisión bibliográfica empírica. Pedagogía Social, 21, 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00530.x.

Orte, C., Amer, J., Ballester, L., March, M. X., Vives, M., & Pozo, R. (2015). The Strengthening Families Programme in Spain: A long-term evaluation. Journal of Children's Services. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-03-2013-0010.

Orte, C., Ballester, L., & March, M. X. (2013). El enfoque de la competencia familiar. Una experiencia de trabajo socioeducativo con familias/The family competence approach. An experience of socio-educational work with families. Pedagogía Social, 21, 13–37. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2013.21.1.

Orte, C., Ballester, L., Vives, M., & Amer, J. (2016). Quality of implementation in an evidence-based family prevention program: “The Family Competence Program”. Psychosocial Intervention, 25(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psi.2016.03.005.

Pascual, B., Sánchez-Prieto, L., Gomila, M. A., Quesada, V., & Nevot, Ll. (2019). Prevention training in the socio-educational field: An analysis of professional profiles. Pedagogía Social, 34, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2019.34.03.

Pascual, B., Vives, M., Oliver, J. Ll., Sánchez-Prieto, L., & Cabellos, A. (2020). La e′′valuación de proceso en los programas de prevención familiar. El estudio de caso del Programa de Competencia Familiar. Orte, C., Ballester, Ll., & Amer, J. Educación familiar. Programas e intervenciones basados en la evidencia. Barcelona: Octaedro.

Perrino, T., Brincks, A., Howe, G., Brown, C. H., Prado, G., & Pantin, H. (2016). Reducing internalizing symptoms among high-risk, Hispanic adolescents: Mediators of a preventive family intervention. Prevention Science, 17(5), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0655-2.

Perrino, T., Pantin, H., Prado, G., Huang, S., Brincks, A., Howe, G., et al. (2014). Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: A synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prevention Science, 15, 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0448-9.

Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381.

Reynolds, C., & Kamphaus, R. (2004). BASC. Sistema De Evaluación De La Conducta De Niños y Adolescentes/Child and Adolescent Behaviour Assessment System. TEA ediciones: Madrid.

Sánchez-García, M. A., Pérez, A., Paino, M., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2018). Ajuste emocional y comportamental en una muestra de adolescentes españoles. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatía, 46(6), 205–216.

Sánchez-Prieto, L., Orte, C., Ballester, L., & Amer, J. (2019). Can better parenting be achieved through short prevention programs? The challenge of universal prevention through Strengthening Families Program 11–14. Child & Family Social Work,, 25(3), 515-525. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12717.

Spoth, R., Guyll, M., & Shin, C. (2009). Universal intervention as a protective shield against exposure to substance use: Long-term outcomes and public health significance. Research and Practice, 99(11), 2026–2033. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.133298.

Spoth, R., Shin, C., Guyll, M., Redmond, C., & Azevedo, K. (2006). Universality of effects: An examination of the comparability of long-term family intervention effects on substance use across risk-related subgroups. Prevention Science, 7(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-006-0036-3.

Stormshak, E. A., Connell, A. M., Véronneau, M.-H., Myers, M. W., Dishion, T. J., Kavanagh, K., et al. (2011). An ecological approach to promoting early adolescent mental health and social adaptation: Family-centered intervention in public middle schools. Child Development, 82(1), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01551.x.

Torío, S., Peña, J. V., & García-Pérez, O. (2015). Parentalidad positiva y formaciónexperiencial: Análisis de los procesos de cambio familiar/positive parenting and experiential training: Analysis of family change processes. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 5(3), 296–315. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.2015.1533.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, UNODC. (2018). World Drug Report 2018. Vienna: United Nations publication.

Van Ryzin, M. J., Stormshak, E. A., & Dishion, T. J. (2012). engaging parents in the family check-up in middle school: Longitudinal effects on family conflict and problem behaviour through the high school transition. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(6), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.255.

Vermeulen-Smit, E., Verdurmen, J. E. E., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2015). The effectiveness of family interventions in preventing adolescent illicit drug use: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(3), 218–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0185-7.

Williams, L. R., Degnan, K. A., Perez-Edgar, K. E., Henderson, H. A., Rubin, K. H., Pine, D. S., ... & Fox, N. A. (2009). Impact of behavioural inhibition and parenting style on internalizing and externalizing problems from early childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(8), 1063-1075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9331-3

Funding

This study funded by Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, Gobierno de España (EDU2016-79235-R)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The families had to sign a consent form that guaranteed confidentiality.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ballester, L., Sánchez-Prieto, L., Orte, C. et al. Preventing Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms in Adolescents Through a Short Prevention Programme: An Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Universal Strengthening Families Program 11-14. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 39, 119–131 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00711-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00711-2