Abstract

Negative parenting practices are thought to be essential for the development of adolescents’ internalizing problems. However, mechanisms linking parental practices to adolescents’ internalizing problems remain poorly understood. A potential pathway connecting parental behaviors to internalizing problems could be through adolescent expressive suppression—the tendency to inhibit the observable expression of emotions.This study examined the indirect effects of three individual parenting practices—poor monitoring, inconsistent discipline and use of corporal punishment—on adolescents’ internalizing problems through adolescents’regular use of expressive suppression in a sample of 1132 adolescents (10–14 years). Structural Equation Modeling indicated that parenting practices were related both directly and indirectly to adolescents’ internalizing problems through their relationship with suppression. Clinical implications and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition into adolescence involves a broad range of changes and developmental tasks that may result in increased negative affect, heightened emotional reactivity and a risk for internalizing symptoms (Larson and Ham 1993). By the age of 15 years, up to 15 % of children and adolescents experience internalizing symptoms, such as depression, anxiety and psychosomatic complaints (Costello et al. 2005). These internalizing symptoms are highly disruptive of adolescents’ social, academic, and interpersonal functioning (Duggal et al. 2001). Moreover, internalizing problems in adolescence are associated with substance abuse, conduct problems and risk for suicide and predict clinically levels of psychopathology in adulthood (Ferdinand et al. 1995). Given the high prevalence and the concurrent and long-term deleterious effect of internalizing symptoms among adolescents, it is crucial to identify the risk factors and the mechanisms by which these problems emerge.

Although the etiology of internalizing problems is clearly complex, one line of research has focused on familial factors, notably, the role of parents (Gil-Rivas et al. 2003; Greenberger and Chen 1996). As emphasized by a meta-analytic review, parenting plays a paramount role in the development, persistence, and diminution of youths’ internalizing symptoms, with as much as 8 % of variation in childhood depression (current and lifetime) explained directly by parenting (McLeod et al. 2007).

Three main components of parenting have been highlighted as paramount with regard to adolescents’ behavioral adjustment: poor supervision/monitoring, harsh discipline (e.g., corporal punishment) and inconsistent discipline (e.g., widely varied severity of punishment for similar transgressions; early termination of punishment in response to coercive behavior by the child) (Dishion and McMahon 1998; Gershoff 2002). Extensive research emphasized these three parenting practices as risk factors for children’s externalizing behaviors (Gershoff 2002; Lahey et al. 2008), but there is also growing support for an association with children’s internalizing symptoms (Bender et al. 2007; Downey and Coyne 1990; duRivage et al. 2015; Galambos et al. 2003; Mackenbach et al. 2014; Rodriguez 2003; van der Sluis et al. 2015).

These important findings notwithstanding, mechanisms through which inconsistent discipline, corporal punishment, and poor monitoring as ineffective parenting strategies are associated with adolescents internalizing behaviors still remain poorly understood. Of the multiple potential mechanisms through which poor parenting might translate into child internalizing symptoms, one of the strongest contenders is children’s emotion regulation (Eisenberg and Spinrad 2004; Morris et al. 2007), which refers to the processes through which individuals consciously and nonconsciously modulate the timing, intensity and duration of their emotions to appropriately respond to environmental demands (Gratz and Roemer 2004; Gross and Muñoz 1995). This idea is supported by the risky families model, whereby a risky familial environment during childhood and adolescence is hypothesized to interfere with the development of means for emotion processing and foster unsophisticated and avoidant coping strategies for stressful situations, which, in turn, may lead to a wide array of negative outcomes, including internalizing symptoms (Repetti et al. 2002).

According to the emotion regulation model proposed by Gross (1998), two major emotion regulation strategies that have been extensively studied are expressive suppression (a response-focused strategy that involves actively inhibiting the observable expression of emotional experience) and cognitive reappraisal (an antecedent-focused strategy that involves reinterpreting an emotion-eliciting situation in a way that modifies its emotional impact) (Gross and John 2003). In the present study, we chose to focus solely on expressive suppression as an emotion regulation strategy for two reasons. First, the use of expressive suppression is more strongly related to anxiety and depressive symptoms than the absence of cognitive reappraisal (Aldao et al. 2010). Second, expressive suppression appears to be one of the most commonly used emotion regulation strategies in adolescents. Gullone et al. (2010) found a greater reliance on suppression for adolescents compared to their older peers, while no difference had been reported for cognitive reappraisal. These findings suggest that expressive suppression may be a particularly relevant risk factor for developing internalizing symptoms during this developmental period.

Parenting behaviors have been shown to make important contributions to the development of children’s emotion regulation abilities (Buckholdt et al. 2014; Holodynski and Friedlmeier 2006). For example, Gresham and Gullone (2012) found that high levels of parental alienation predicted more use of suppression among adolescents. Similarly, punitive reactions to children’s emotional displays had been associated with maladaptive emotion regulation behaviors, such as suppression and avoidance (Berlin and Cassidy 2003). Moreover, exposure to negative and harsh parental behaviors, particularly the use of punishment or alienation, have been longitudinally linked to child emotion dysregulation in form of overregulation, defined as suppressing the expression of emotion (Eisenberg et al. 1996; Gottman et al. 1996; Shipman et al. 2007). These findings point out that negative and harsh parental responses can lead to both enhanced arousal and a tendency to inhibit the expression of negative emotions (Morris et al. 2007).

In turn, the use of expressive suppression as a main emotion regulation strategy has been posited as a precursor of internalizing problems. The use of expressive suppression can translate into depressive symptoms, as has been shown by previous research on adolescents (Betts et al. 2009) and adults (e.g., Gross and John 2003; Zhao and Zhao 2015). There is also evidence for a relationship between suppression and anxiety symptoms. For example, Campbell-Sills et al. (2006) found that use of emotion suppression is elevated in anxiety disordered populations. In addition, longitudinal studies have linked emotion overregulation in early childhood with later internalizing problems (Keenan and Hipwell 2005). Taken together, these findings suggest the feasibility of an indirect pathway through which parental inconsistent discipline, use of corporal punishment and poor monitoring are each associated with adolescents’ internalizing behaviors via adolescents’ regular use of expressive suppression.

To our knowledge, no study has yet explored this potential mechanism by looking at these three specific parental behaviors in relation with adolescents’ use of suppression and internalizing problems. In addition, the onset of adolescence marks critical points in youths’ stressors and affect sensitivity (Spear 2009). Pubertal related increases in emotional reactivity are part of a normative process, but may result in emotion dysregulation and may activate psychopathological vulnerabilities among at-risk adolescents (Spear 2009). Therefore, identifying mechanisms linking exposure to familial stressors in the form of negative parental practices and internalizing difficulties during this developmental period is crucial, in order to develop effective interventions.

The aim of the current paper was to expand existing research by exploring the indirect effects of inconsistent parenting, corporal punishment, and poor monitoring on adolescents’ internalizing symptoms through adolescents’ use of expressive suppression as an ineffective emotion regulation strategy. It was hypothesized that each of the three parenting practices—inconsistent parenting, corporal punishment, poor monitoring—will be associated with adolescents’ use of expressive suppression, which in turn, will be associated with adolescents’ internalizing problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were 1132 adolescents (611 boys and 521 girls) enrolled in public middle school, aged between10 to 14 years (M = 11.67; SD = 0.77). The ethnic composition of the sample was representative of the schools from which we sampled (92.6 % Romanians, 5.7 % Hungarians, 1.4 % Romani, 0.3 % other).

Procedure

Data were collected from schools in several counties. First, school principals were contacted and informed about the project. Passive consent was sought from parents, who received a leaflet with the study specifics and were offered the possibility to opt out. Active consent was obtained from the participants (i.e., the students). Before the questionnaires were administered, participants were informed about the objective of the current study, were assured of the confidentiality of their responses, as well as of the voluntary nature of their participation and their right to drop out at any time during the study. Data collection was carried out at school by trained researchers, who were assisted by the lead teacher. The time required for completion was relatively high (90–120 min). At the end of an hour, participants were given a small gratification (e.g., chocolate, candies). A raffle was also organized and the winner received a monetary award. Each child was given a multi-digit code. Draws were conducted for each digit, in the presence of three researchers. The child whose corresponding number was drawn was declared as the winner. Both the raffle procedure and the result were published on an online platform and the link was disseminated to all participating families and schools.

All variables of interested were collected through self-reports. The questionnaires were translated from English into Romanian by a bilingual Romanian researcher who lives in the United Kingdom. They were back-translated into English by a second native Romanian speaking researcher. The back-translation and the original English version were then compared for accuracy by a native English speaking researcher.

Measures

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, ERQ (Gross and John 2003)

Expressive suppression was measured using a sub-scale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gullone and Taffe 2012) which comprises 4 items about the degree to which individuals inhibit the expression of their emotions. For adolescents, each item is rated on a 5 point scale (Gullone et al. 2010). The overall scale provides a single total score of expressive suppression and has been shown to have good and high convergent and discriminant validity. Data on expressive suppression were available on all items for 98.1 % of the sample.

Alabama Parenting Questionnaire, APQ (Frick 1991)

Inconsistent discipline, corporal punishment and poor monitoring were assessed with the corresponding subscales from the APQ. The inconsistent discipline subscale has six items (e.g., “The punishment your parents give depends on their mood.”). The corporal punishment subscale has three items (e.g., “Your parents slap you when you have done something wrong.”). The poor monitoring subscale has 10 items (e.g., “You go out without a set time to be home.”). For each of these three subscales children rate each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) through 5 (always) depending on how frequently the behavior typically occurs in the home. The original version of the instrument has moderate internal consistency (alpha ranged from .58 to .80) (Escribano et al. 2013). Data were available for 93.7 % of the sample in relation to poor monitoring, 96.2 % of the sample in relation to inconsistent discipline and 97.6 % of the sample in relation to corporal punishment.

Youth Self-Report, YSR (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001)

Internalizing problems were measured through the YSR. Adolescents used a 3 point scale (from 0 = not true to 2 = very true or very often) to report on a range of difficulties, including emotional problems, behavioral problems, social relationships and academic performance. In the present study, only the Internalizing Scale was used. The YSR Internalizing Scale is the sum of scores for Anxious/ Depressed, Withdrawn/ Depressed and Somatic Complaints syndromes and consists of 31 items. The YSR has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). The Omega reliability obtained in our sample was .94.

Data Analyses

First, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to obtain total scores for expressive suppression, poor monitoring, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment. Total scores for internalizing problems were estimated within the main model because although only 7 children (0.6 % of the sample) had missing values on the entire questionnaire, partial missing data patterns were observed for 16 % of the sample.

The main hypotheses were tested using a Structural Equation Model applied to the factor scores of parental practices and suppression, as well as a factor representing internalizing problems. All models were estimated using Mplus v.7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2011) and the Weighted Least Squares with Robust Means and Variances estimator, which is suitable when the dependent variables are categorical in nature (as were the questionnaire items) and in the presence of missing data patterns.

Results

Total scores for the three types of parental practices and child expressive suppression were obtained from confirmatory factor analyses. With regard to expressive suppression, the model fit was good: χ²(2) = 3.551 (p = 0.17), CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00 and RMSEA = .026, 90 % CI [.00, .07], the average standardized factor loading was .61 and the scale achieved an Omega reliability value of .71. For poor monitoring, the model (χ²(31) = 80.505, p < .01) fitted the data well: CFI = .98, TLI = .98 and RMSEA = .038, 90 % CI [.028, .048]; the average standardized factor loading was .52 and the scale Omega reliability was .81. With regard to inconsistent discipline, the model (χ²(8) = 21.851, p = .01) showed good fit to the data: CFI = .98, TLI = .96 and RMSEA = .039, 90 % CI [.020, .059]; the average standardized factor loading was .41 and the scale Omega reliability was .58. Finally, with regard to corporal punishment, the model was just-identified (i.e., model fit could not be evaluated) because the scale comprises only 3 items. However, all the factor loadings were very high, with an average factor loading of .82, and the scale achieved an Omega reliability value of .87.

Descriptive statistics for all measures (used here as sum scores to aid the interpretation of means), as well as bivariate correlations among all the study variables are presented in Table 1. Significant positive correlations were found between parental inconsistent discipline and adolescents’ suppression, parental corporal punishment and adolescents’ suppression as well as between parental poor monitoring and adolescents’ suppression. Adolescents’ habitual use of suppression was significantly and positively related to their internalizing problems. Similarly, there was a positive significant association between inconsistent discipline and internalizing problems, corporal punishment and internalizing problems, and poor monitoring and internalizing problems. In other words, adolescents who reported frequent use of each of the three parental practices also demonstrated higher levels of internalizing symptoms.

To investigate whether negative parental practices were indirect predictors of heightened internalizing problems through elevated levels of expressive suppression, a structural equation model was specified. The measurement part of the model referred to internalizing problems. Here, three first-order factors were specified, representing “anxious/ depressed”, “withdrawn/depressed” and “somatic complaints” syndromes. A second-order factor was then applied to the three first-order factors to obtain an overall score of internalizing problems. The other variables (i.e., expressive suppression and the 3 types of parental practice) were conceptualized as factor scores.

The structural part of the model included regression paths from parental poor monitoring, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment to adolescent expressive suppression and internalizing problems, as well as from expressive suppression to internalizing problems. Indirect effects were also computed.

The model (χ²(544) = 1251.155, p < .01) fitted the data well: CFI = .95, TLI = .95, and RMSEA = .034, 90 % CI [.031, .036]. With regard to the measurement model, all items loaded significantly onto their respective first-order factors, with an average standardized loading of .60. The loadings of the first-order factors onto the second-order were also high, with an average standardized loading of .94.

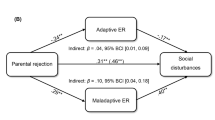

As shown in Fig. 1, each type of parental practice was a significant predictor of adolescent’s expressive suppression, such that all the estimated non-standardized path coefficients were significant: inconsistent discipline, β = .16, 95 % CI [.06, .26], p = .001; poor monitoring, β = .26, 95 % CI [.17, .35], p < .001; corporal punishment, β = .07,95 % CI [.04, .11], p < .001. Adolescents’ suppression significantly and positively predicted their internalizing problems, β = .23, 95 % CI [.15, .32], p < .001. Direct paths from the parenting practice variables to internalizing problems were also computed: inconsistent discipline, β = .16, 95 % CI [.01, .31], p = .04; poor monitoring, β = .49, 95 % CI [.36, .62], p < .001 and corporal punishment, β = .10, 95 % CI [.05, .16], p < .001. All indirect effects were statistically significant: inconsistent discipline, β = .04, 95 % CI [.01, .06], p = .005; poor monitoring, β = .06, 95 % CI [.03, .09], p < .001; corporal punishment, β = .02, 95 % CI [.01, .03], p = .003.

Structural equation model of the relationship between parental practices on internalizing problems via expressive suppression. Parameters represent non-standardized coefficients (β). Curved arrows represent correlations between predictor variables. The measurement model (referring to the factor structure of Internalizing problems) was omitted for clarity. **p<.01; *p<.05

Discussion

Given the relationship between ineffective parenting practices and children’s internalizing problems, the next step is to understand how parenting influences adolescents’ mental health. Thus, an important contribution of this study is the model that was tested, which proposed a mechanism linking specific parenting strategies and adolescent’s internalizing problems. Results were partially consistent with our prediction that adolescents’ use of expressive suppression serves as a pathway through which each of the three negative parental behaviors may relate to adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. Inconsistent discipline, corporal punishment and poor monitoring were each related to youths’ emotional distress, both directly and indirectly through their link with adolescents’ suppression. The proposed model explained 18 % of variance in internalizing problems. This finding is consistent with previous research on different populations, including samples of European adolescents, demonstrating that, at least in part, the family context translates into poor child behavioral adjustment through its links with children’s emotion regulation (Denham et al. 2004; Eisenberg and Spinrad 2004; Mackenbach et al. 2014; Morris et al. 2007). A potential explanation for the finding that emotion regulation might be a mechanism through which negative parenting practices translate into adolescents’ internalizing symptoms is provided by theoretical models suggesting that it is likely that chronic stress during childhood and adolescence lead to deficits in emotion regulation (Cicchetti and Toth 2005; Repetti et al. 2002). Negative parenting behaviors, such as lacking consistence to follow through with commands or the use of physical corrections, may represent salient stressors in youths’ lives, which elicit negative emotions such as anger, fear or sadness. Managing these intense negative emotions is effortful and reduces the coping resources available to respond promptly and adaptively to other sources of emotional arousal (Repetti et al. 2002) which in time may translate into inflexible and poor emotion regulation styles and poor mental health. In addition, the current study replicates findings from previous studies showing the detrimental effects of regular use of expressive suppression (Betts et al. 2009).

On the other hand, over and above the indirect effects through expressive suppression, parenting practices were also directly associated with child internalizing problems, suggesting that there might be other pathways connecting familial risk factors posited in this study and adolescentsʼ internalizing problems. For example, two main domains of cognitive functioning posited to act as mechanisms through which parental over-control promotes child anxiety are outcome expectancy biases and children’s locus of control (e.g., Bögels & Brechman-Toussaint 2006; Chorpita & Barlow 1998). Therefore, future studies should examine cognitive factors that might explain the relationship between parental inconsistent behavior, poor monitoring, use of corporal punishment and children’s emotional distress. Moreover, although significant, the association between parenting behaviors, adolescents’ suppression and their internalizing behaviors was moderate in magnitude. A potential explanation could be the fact that the use of suppression may be adaptive in the short run, especially in relation to the negative parental behaviors, whereas its long-term detrimental effects are not yet fully expressed in youths’ behavior.

The findings of the present study are proposed to have several implications. First, the current study is the first to model indirect pathways among dysfunctional parenting practices, expressive suppression and internalizing problems in adolescents. These findings could serve as a guide for testing and developing future prevention programs using emotion regulation education. Previous research support the effectiveness of an emotional education program in youth psychological adjustment (Donegan and Rust 1988). Future studies could test the effectiveness of intervention aiming to reduce the use of expressive suppression. Second, this study underscore the importance of targeting maladaptive parenting behaviors in order to prevent or to reduce adolescents’ internalizing behaviors, an area that has so far been under-supported (Barmish and Kendall 2005). Behavioral parent training programs address these three inadequate parenting practices in children with externalizing problems, but children with internalizing behaviors could also benefit from interventions. This study suggests that techniques targeting emotion regulation should be an additional component of clinical interventions for adolescents confronted with parental behavior stressors, in order to overcome the negative mental health sequelae of less suitable parenting behaviors. The results provide additional support for the significance of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) in internalizing problems among adolescents. DBT emphasizes the improvement of adaptive and positive emotion regulation strategies and relies on both cognitive-behavioral techniques and acceptance-based coping styles (e.g., Linehan 1993; McLaughlin et al. 2009a). Note that suppressing the expression of emotions may represent an adaptive response within the familial context, but in relation to long-term psychological well-being it is an ineffective and costly regulation strategy (Gross and Thompson 2007). As a result, questions about the adaptiveness and maladaptivness of this specific emotion regulation strategy should be addressed in relation to specific outcomes; interventions should provide youths with alternative strategies, which help them not to escalate the negative behaviors of their parents and also provide subjective relief.

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow us to draw causal inferences about the influence of parenting practices on children’s emotion regulation and internalizing symptomatology and further studies are needed to disentangle the formation of patterns of self-regulation within the context of the family and peer networks. Indeed, some existing research suggests that development of ER strategies is a bidirectional process (Calkins 1994; Morris et al. 2007). Therefore, it is likely that children’s use of expressive suppression elicits more negative parenting practices, which, in turn, exacerbate children’s reliance on suppression, leaving them more vulnerable to internalizing problems. In consequence, future studies should consider a longitudinal examination of the current model, in order to determine causality. Second, an important limitation of our study is the low internal consistency of the inconsistent discipline measure. Although the significant relationships suggest that the relative low omega coefficient for this construct did not create a major problem, the findings implicating this measure should be interpreted with caution. Third, it is important to note the overall low levels of internalizing symptoms displayed in our sample, so further studies are needed to extend our results to clinical populations.Another limitation of this research involves the reliance on adolescents’ reports for measuring both parenting practices and adolescents’ behavior problems. Although adolescent self-report tools tap into valuable internal information not available from other informants (Walden et al. 2003), future research may benefit from the use of multiple informants in assessing the variables of interest. Moreover, we only examined the emotion regulation strategy of expressive suppression, but there are a myriad of potential emotion regulation strategies. Future research should also consider other commonly used strategies among adolescents to attempt a more comprehensive investigation of the mechanisms underlying internalizing symptomatology. Moreover, a meta-analysis concluded that particular regulatory strategies have stronger relationships to specific psychopathologies (Aldao et al. 2010), suggesting to disaggregate broad bands syndromes and to examine them in relation with specific emotion regulation modalities.

In addition, as stated previously, additional factors need to be examined in the context of testing the current model. For example, how may cognitive factors contribute to our understanding of the link between parenting behaviors, adolescents’ emotion regulation deficits and internalizing behaviors?

This study emphasizes the impact of particular parental behaviors on adolescents’ adjustment and identifies adolescents’ emotion dysregulation in the form of expressive suppression as a mechanism through which parental risk factors, namely inconsistent discipline, use of corporal punishment and poor monitoring, may be related to internalizing behaviors among adolescents. Given that each of the parenting practices tested here was related both directly and indirectly to children’s emotional distress through their relationship with expressive suppression, future models including other potential pathways in this association need to be explored.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004.

Barmish, A. J., & Kendall, P. C. (2005). Should parents be co-clients for cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious youth? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 569–581.

Bender, H. L., Allen, J. P., McElhaney, K. B., Antonishak, J., Moore, C. M., Kelly, H. O., & Davis, S. M. (2007). Use of harsh physical discipline and developmental outcomes in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 19(1), 227–242. doi:10.1002/jcb.20739.

Berlin, L. J., & Cassidy, J. (2003). Mothers’ self-reported control of their preschool children’s emotional expressiveness: a longitudinal study of associations with infant–Mother attachment and children’s emotion regulation. Social Development, 12(4), 477–495. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00244.

Betts, J., Gullone, E., & Allen, J. S. (2009). An examination of emotion regulation, temperament, and parenting style as potential predictors of adolescent depression risk status: a correlational study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 473–485. doi:10.1348/026151008X314900.

Bögels, S. M., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. L. (2006). Family issues in child anxiety: attachment, family functioning, parental rearing and beliefs. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(7), 834–856. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.08.001.

Buckholdt, K. E., Parra, G. R., & Jobe-Shields, L. (2014). Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation through parental invalidation of emotions: implications for adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 324–332. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9768-4.

Calkins, S. D. (1994). Origins and Outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2-3), 53–72. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01277.x.

Campbell-Sills, L., Barlow, D. H., Brown, T. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2006). Acceptability and suppression of negative emotion in anxiety and mood disorders. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 6(4), 587–595. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.4.587.

Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124(1), 3–21.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2005). Child maltreatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 409–438. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029.

Costello, E. J., Egger, H., & Angold, A. (2005). 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(10), 972–986. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f.

Denham, S. A., Caal, S., Bassett, H. H., Benga, O., & Geangu, E. (2004). Listening to parents: cultural variations in the meaning of emotions and emotion socialization. Cognition Brain Behavior, 8, 321–350.

Dishion, T. J., & McMahon, R. J. (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: a conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1(1), 61–75.

Donegan, A., & Rust, J. (1988). Rational emotive education for improving self-concept in second-grade students. Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 36, 248–256.

Downey, G., & Coyne, J. C. (1990). Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108(1), 50–76.

Duggal, S., Carlson, E.A., Sroufe, L.A., & Egeland, B. (2001). Depressive symptomatology in childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 13(1), 143–164.

duRivage, N., Keyes, K., Leray, E., Pez, O., Bitfoi, A., Koç, C., & Kovess-Masfety, V. (2015). Parental use of corporal punishment in Europe: intersection between public health and policy. PLOS ONE, 10(2), e0118059. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118059.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Murphy, B. C. (1996). Parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: relations to children’s social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development, 67(5), 2227–2247.

Eisenberg, N., & Spinrad, T. L. (2004). Emotion-related regulation: sharpening the definition. Child Development, 75(2), 334–339. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00674.x.

Escribano, S., Aniorte, J., & Orgilés, M. (2013). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) for children. Psicothema, 25(3), 324–329. doi:10.7334/psicothema2012.315.

Ferdinand, R. F., Verhulst, F. C., & Wiznitzer, M. (1995). Continuity and change of self-reported problem behaviors from adolescence into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 680–690.

Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama parenting questionnaire. Unpublished rating scale, University of Alabama.

Galambos, N. L., Barker, E. T., & Almeida, D. M. (2003). Parents do matter: trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Development, 74(2), 578–594.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579.

Gil-Rivas, V., Greenberger, E., Chen, C., & Montero y López-Lena, M. (2003). Understanding depressed mood in the context of a family-oriented culture. Adolescence, 38(149), 93–109.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 243–268. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94.

Greenberger, E., & Chen, C. (1996). Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: a comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology, 32(4), 707–716. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.707.

Gresham, D., & Gullone, E. (2012). Emotion regulation strategy use in children and adolescents: the explanatory roles of personality and attachment. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 616–621. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.016.

Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 224–237. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348.

Gross, J. J., & Muñoz, R. F. (1995). Emotion regulation and mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 2(2), 151–164. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.1995.tb00036.x.

Gross, J. J., Thompson, R. A., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). New York: Guilford Press.

Gullone, E., Hughes, E. K., King, N. J., & Tonge, B. (2010). The normative development of emotion regulation strategy use in children and adolescents: a 2-year follow-up study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(5), 567–574. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02183.x.

Gullone, E., & Taffe, J. (2012). The emotion regulation questionnaire for children and adolescents (ERQ–CA): a psychometric evaluation. Psychological Assessment, 24(2), 409–417. doi:10.1037/a0025777.

Holodynski, M., & Friedlmeier, W. (2006). Development of emotions and emotion regulation. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Keenan, K., & Hipwell, A. E. (2005). Preadolescent clues to understanding depression in girls. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8(2), 89–105.

Lahey, B. B., Van Hulle, C. A., Onofrio, B. M. D.’, Rodgers, J. L., & Waldman, I. D. (2008). Is parental knowledge of their adolescent offspring’s whereabouts and peer associations spuriously associated with offspring delinquency? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(6), 807–823. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9214-z.

Larson, R., & Ham, M. (1993). Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: the relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 130–140. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.130.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. First Edition, New York: The Guilford Press.

Mackenbach, J. D., Ringoot, A. P., van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., Jaddoe, V. W. V., Hofman, A., & Tiemeier, H. W. (2014). Exploring the relation of harsh parental discipline with child emotional and behavioral problems by using multiple informants. The generation R study. PLOS ONE, 9(8), e104793. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104793.

McLaughlin, K. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Hilt, L. M. (2009a). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting andClinical Psychology, 77(5), 894–904. doi:10.1037/a0015760.

McLeod, B. D., Weisz, J. R., & Wood, J. J. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(8), 986–1003. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02183.x.

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development (Oxford, England), 16(2), 361–388. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2011). Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén&Muthén.

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330–366.

Rodriguez, C. M. (2003). Parental discipline and abuse: potential affects on child depression, anxiety, and attributions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 809–817. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00809.x.

Shipman, K. L., Schneider, R., Fitzgerald, M. M., Sims, C., & Swisher, L., et al. (2007). Maternal emotion socialization in maltreating and nonmaltreating families: implications for children’s emotion regulation. Soc. Dev., 16, 268–85.

Spear, L. P. (2009). Heightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: Implications for psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 87–97. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000066.

van der Sluis, C. M., van Steensel, F. J. A., & Bögels, S. M. (2015). Parenting and children’s internalizing symptoms: how important are parents?. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3652–3661. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0174-y.

Walden, T. A., Harris, V. S., & Catron, T. F. (2003). How I feel: a self-report measure of emotional arousal and regulation for children. Psychological Assessment, 15(3), 399–412. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.399.

Zhao, Y., & Zhao, G. (2015). Emotion regulation and depressive symptoms: examining the mediation effect of school connectedness in Chinese late adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 40, 14–23. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.12.009.

Acknowledgments

Part of this research was supported by a grant from theRomanian Executive Unit for Financing Education, Higher Research, Development and Innovation (the ‘‘Effectiveness of an empiricallybased web platform for anxiety in youths’’, Grant Number PN-II-PTPCCA-2011-3.1-1500, 81/2012) awarded to Dr. Anca Dobrean.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balan, R., Dobrean, A., Roman, G.D. et al. Indirect Effects of Parenting Practices on Internalizing Problems among Adolescents: The Role of Expressive Suppression. J Child Fam Stud 26, 40–47 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0532-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0532-4