Abstract

The transition to institutional care often implies the separation from a dysfunctional environment, marked by neglect, abandonment and lack of emotional responsiveness, which makes youth more vulnerable to the development of deviant behavior. The quality of the relationship established with significant figures within the institution as well as with teachers is suggested as a protective factor for the development of resilience and the detachment from deviant behaviour. The present study aims to test the predictive effect of the quality of relationship to institutional caregivers and teachers on the development of resilience and deviant behaviour in institutionalized adolescents. We also intend to test the mediating effect of resilience in the previous association. The sample was composed by 202 institutionalized adolescents, 12–18 aged (M = 14.96, SD = 1.80), and from both genders. Data were collected using self-report questionnaires. The results demonstrated that the quality of relationship with significant figures was positively associated with resilience and may play an important role in preventing deviant behaviour. There was also a total mediation effect of resilience on the association between quality of relationship with significant figures and development of deviant behaviour. The results suggest that the affective reorganization of institutionalized adolescents can be promoted by the establishment of safe havens, which reflect feelings of belonging and acceptance, facilitating a more adaptive experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to attachment theory, the establishment of significant affective bonds constitutes a vital process in the development of the human being, present throughout life, from birth till death (Bowlby, 1979). The quality of the bonds developed with the primary attachment figures allows the creation of secure internal working models which enables youth to become more competent in dealing with adversity (Bowlby, 1969). However, experiencing adverse events such as violence and abuse, loss or separation from significant figures, has been described as damaging to emotional development, compromising the construction of personality and affecting adolescents at a cognitive, behavioral and emotional level (Bowlby, 1951). A dysfunctional family environment can make youth be confronted with problems in relation to the emotional and affective care, marked by the unavailability and instability of the caregivers, especially due to the presence of some risk factors related to social economic difficulties and to crime (Sandler et al., 2003).

This issue takes on increasing importance among adolescents in residential care, in which the transition to a new context can constitute in many cases situations of risk and vulnerability. Adolescents that live in residential care due to abandonment, parental neglect or lack of family socio-economic conditions, in most cases, presented a lack of support from extended family. Adolescents who were institutionalized because of mental disabilities, or disorders, or additional motives of deviant behaviours (conduct disorders or substance abuse) were not included in this study, in order to avoid medley with youth that is placed in an institution with specific conditions, as mental and social rehabilitation, and most of time in internment condition.

The role of the significant figures (e.g. non-primary caregivers, institutional staff, teachers and school staff), which monitor their course has been described in the literature as important to the adjustment process, functioning as a protection factor when adolescents are faced with adverse situations (Howard & Johnson, 2004). The relationships with the institution staff are important because they are able to offer personal, affective and social quality responses allowing positive integration and adjustment to the transition process (Mota & Matos, 2008; Poletto & Koller, 2008). These satisfying relationships with significant figures promote then the development of protective factors toward emotional and behavioral problems.

The caregivers of the institution constitute the main figures within the institutions that can help youth work out their problems, having close access to emotional situations experienced by them (Junqueira & Deslandes, 2003). Although most of the institution staff doesn’t constitute attachment figures, they tend to be seen as a safe haven in situations in which they are available to support the anguishes, fears, expectations and joys of children and adolescents (Zegers, 2007). In this way these bonds can function as an opportunity for an internal organization that promotes the development of more adaptive and positive internal working models of self and of others (Mota & Matos, 2010).

However, besides the institution staff, the youths’ emotional and affective experiences can be molded by other significant figures outside the institution, for example, the teachers and school staff (e.g. Pesce, Assis, Santos, & Oliveira, 2004; Rutter, 2006). The institution and the school are the main socializing and educational agents, working as role models and transmitting values and skills. Teachers who are available and know how to listen become fundamental figures in the emotional regulation and psychosocial integration process of adolescents. Besides this, the youths’ awareness that the adults are available to take care of them and to establish a relationship seems to have a positive effect in the achievement of the defined goals, both at an academic and at a social and emotional level (Wentzel, 2002). Simsek, Erol, Öztop, and Munir (2007) emphasized in a study conducted on 461 adolescents that permanent contact and affective involvement with teachers and institution staff works as a favorable indicator for perception of greater social support. In this sense, the contact with alternative significant adult figures in the school allows institutionalized adolescents to fulfil, at least in part, some of their emotional and affective needs.

Although the importance of the construction of safe relationships within and outside the institutional context is recognized, the role of both teachers and institution staff as significant figures for institutionalized adolescents is rarely addressed in the empirical literature. Based on an ecological perspective and on attachment theory, the current study focuses on the quality of relationship to significant figures—both teachers and institution staff—as facilitators of the internal reorganization of youth, promoting resilience and helping to prevent deviant behavior.

Caregivers and The Resilient Development of Youth

The development of secure attachment relationships is directly related to the human being’s capacity to face up to difficulties, which promotes resilience (Bowlby, 1969). According to attachment theory, resilience constitutes a developmental construction, represented in the tendency to look for support and comfort in situations of adversity among emotional close figures (Sroufe, 1997). This issue has increasing importance in the case of institutionalized youth, in which the resilience processes can be observed as they effectively benefit from a network of support (Siqueira & Dell’Aglio, 2006; Yunes, Miranda, & Cuello, 2004).

Resilience is not a synonym for resistance or for total adaptation to adversity, it refers to more than the simple return to the state in which one was before the traumatic situation. According to Rutter (2006) resilience stresses the positive aspects and the potential to overcome, that is, the capacity the individual has of constructing new paths, of recovering his/her development from the breaking point on and of reconstructing him/herself. As it is, being resilient implies the development of competences, despite the experience of adverse situations.

Some authors defend that the functioning of resilience is based on the interaction of defensive processes of intrapsychic nature and on internal (personal and social competences and self-perception) and external (family, peers, school and community) protection factors (e.g., Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten & Wright, 2010). As a living system, each individual has the double function of self-regulation and organization, based on his/her own resources, on the closest significant figures and on the social network with the widest range (Luthar et al., 2000).

In this study resilience is therefore conceptualized as a multidimensional construct that taps interrelated psychological components such as perseverance, serenity, self-confidence, sense of life and self-sufficiency. These have been used in a variety of studies with adolescents and adults related to the resilience research domain (e.g. Damásio, Borsa, & Silva, 2011; Lundman, Strandberg, Eisemann, Gustafson, & Brulin, 2007; Portzky, Wagnild, Bacquer, & Audenaert, 2010). Kirk and Day (2011) pointed that the development of life skills, self-concept and the meaning of life contributes to a positive adaptation of institutionalized young people that facilitates educational transitions.

The possibility for youth to build stable and satisfying relationships with teachers and other adults within the institution is of fundamental importance in the development of resilient processes. Sensitive and available adults can promote acceptance and personal integration, facilitating a positive adaptation process (Lindsey et al., 2008; Yunes et al., 2004). This way, the quality of the bonds with the new figures of affection allows youth to organize themselves internally, increasing their affective maturity and their capacity to deal favorably with adverse situations. Resilience is related to the context of which the individual is a part, enabling situations of crisis and adversity to be overcome (Poletto & Koller, 2008). In this sense and in what concerns institutionalized youth, resilience can be considered a phenomenon of psychosocial growth, in which the caregivers represent the main promoters of this process (Junqueira & Deslandes, 2003).

Caregivers and Protection in Response to Deviant Behavior

In light of what has been discussed, care conditions grounded on secure relationships with the caregiver tend to make youth less vulnerable when in contact with adversity (Massimo, Van Ijzendoor, Speranza, & Tambelli, 2000; Siqueira, Betts, & Dell’Aglio, 2006). This issue becomes even more relevant when considering that these relationships also promote protection against the development of deviant behaviors (Harland, Reijneveld, Brugman, Verloove-Vanhorick, & Verhulst, 2002; Lerner, Walsh, & Howard, 1998; Sandberg & Rutter, 2005).

Deviant behaviors are characterized by refusal to obey rules, however it does not necessarily imply criminal offenses punishable by law (Emler & Reicher, 1995, 2005). Behavior is deviant in relation to a certain society in which that behavior arises. Each society defines socially acceptable behaviors and so defines deviant behaviors as well. These behaviors can be expressed in acts that infringe the law, such as the use of weapons, drug dealing, driving without a license or theft in a public place or acts that violate social standards, for example, smoking or alcohol consumption (Sanches, Gouveia-Pereira, & Carugati, 2012).

Adolescence is often suggested as a period of challenges, marked by the need to experiment and exceed limits (e.g. Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005), and in which the nature of the transition and adaptation to new external contexts, in this case the institution, is designed as a situation which reorganizes personal representations of others and of the self. Research showed that the expression of deviant behaviors seems to be more common among youth between the ages of 12 and 17 (Warr, 2002). This age group is characterized by a process of internal reorganization and it is at this time that youth construct their social values (Loeber, Farrington, & Petechuck, 2003; Marcotte, Marcotte, & Bouffard, 2002).

The literature has been suggesting that secure affective bonds have a prospective influence on the psychosocial and emotional functioning and on the adaptive nature of the responses to the developmental challenges (Lopez & Brennan, 2000). Although scarce, studies concerning the institutional context suggested that the security in the relationship with significant figures is related to better adaptation outcomes and significantly mitigates the appearance of non-adaptive behaviors. A study conducted by Sanches et al. (2012) on 331 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 19 concluded that the perception of teachers as fair-minded figures in relation to their behavior and to the affective relationships they establish is related to a diminished involvement of those adolescents in deviant behaviors.

Besides the connection with the school, the quality of the bond with the institution staff is a relevant variable in the promotion of feelings of confidence, social competence and emotion regulation (Mota & Matos, 2008; Zegers, Schuengel, Ijzendoorn, & Janssens, 2006). Effectively when youth are able to feel cared for and protected, they are able to establish quality affective relationships, distancing themselves from socially inadequate conducts (Lindsey et al., 2008). Also, Zegers (2007) suggested that caregivers in institutions can encourage adolescents to improve their relationships and help overcome their problematic behaviors. Besides this, these figures seem to be seen, in many cases, as substitutes for parental figures, being that they are available to support their anguishes, fears, expectations and joys. So it can be assumed that their role in the process of emotional regulation and psychosocial integration of institutionalized adolescents is fundamental. Studies showed that secure emotional attachment to significant figures decreases the likelihood of delinquent involvement (Rebellon, 2002) while insecure attachment has been found to be a common characteristic among delinquent youth (Warr, 2005).

Also, other authors pointed out that throughout adolescence the feeling of being socially accepted and valued is of extreme relevance (Sanches et al., 2012). If youth feel rejected and belittled, they tend to search for social recognition in other ways, frequently characterized by indiscipline (Carroll, Houghton, Hattie, & Durkin, 1999). In this sense, the contexts in which youth participate have a significant effect on their lives, namely in the construction of identity, development of feelings of confidence, social competences and emotional regulation (Mota & Matos, 2008).

Aim

This study intends to analyze the role of teachers and institution staff as promoters of resilient development and deviant behaviors avoidance. We highlight the effect of resilience on the dynamics of construction of quality affective relationships that provide a healthy progression in the context of the institution. In this study, deviant behaviors are defined as the result of internal conflicts, which develop in a dysfunctional environment, in which youth, when constantly exposed to adversity, express their pathology through dysfunctional behaviors (Emler & Reicher, 1995, 2005).

First we will observe the associations between quality of the bond to significant figures (teachers and the institution staff), resilience and deviant behavior. Second, we will test differences in the quality of relationship with significant figures, resilience and deviant behavior as a function of age and gender. Third, we will analyze the contribution given by the quality of the bonds established with teachers and the institution staff to the prediction of resilience and deviant behaviors. Finally, we will test the mediating role of resilience in the association between the quality of the bond to significant figures (teachers and the institution staff) and deviant behavior.

Method

Participants

This study was conducted on 202 adolescents who live in care institutions and whose age ranges from 12 to 18 (M = 14.96; SD = 1.80), 92 boys (45.5 %) and 110 girls (54.5 %). The level of schooling varies from 5th to 12th grade (M = 8.25; SD = 1.69). The sample was collected mostly in religious residential institutions in the North and Center of Portugal. These adolescents live in institutions due to abandonment, parental neglect or lack of family socio-economic conditions. Portuguese child welfare system includes various forms of assistance in accordance with the cause for institutionalization. Adolescents who were institutionalized because of mental disabilities/disorders, or additional motives of deviant behaviours (conduct disorders or substance abuse) were not included in this study, in order to avoid medley with youth that is placed in an institution with specific conditions, as mental and social rehabilitation, and most of time in internment condition. Regarding the length of institutionalization, 17 (8.5 %) adolescents lived in the institution for 6 months or less; 82 (41.3 %) between 6 months and 3 years, 91 (45.6 %) between 3 and 10 years, and 9 adolescents (4.5 %) were living for more than 10 years in the institution (Table 1).

The intervention program of the institutions reflects a concern with the adaptive integration of young people in order to prepare deinstitutionalization and promote autonomy, according to the “Challenges, Opportunities and Change Plan” (COC), developed in 2007 (Institute of Social Security, ISS, 2010). Caregivers help children and young people to deal with adverse developmental histories, by encouraging adaptive emotion regulation and by building trust in self and in the others. This plan reinforces the capacity of the whole system of protection to act preventively, through the implementation of individual socio-educational projects, promoting the autonomy of the adolescent and facilitating reintegration into the nuclear family, when possible.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire Includes individual information (e.g. age, gender, school grade), as well as, school and institution information (e.g. conditions, habits, and perception of adaptation, how long live in institution).

Relationship to Significant Figures Questionnaire (Mota & Matos, 2005) It was used to assess the perception of the quality of the relationship to teachers, school staff and institution staff. It is constituted by 28 items and participants respond according to a Likert type scale of 6 points. In this study we used only the dimensions concerning the quality of the relationship to teachers (7 items; “I feel sad when a teacher gets angry with me”; Cronbach α = .79), and to the institution staff (14 items; “Some members of institution staff where I live worry about me”; Cronbach α = .91). It presents adequate indexes of adjustment in the confirmatory factor analysis: CFI = .975, RMR = .055 e RMSEA = .077, χ2(21) = 45.63, Ratio = 2.17; p = .001.

Deviant Behaviors Scale (Gouveia-Pereira & Carita, 2005) Evaluates the frequency which deviant behaviors occurred within the last 2 years and in different contexts, such as school, home or public places. This self-report scale is constituted by 41 items based on a Likert type scale of 6 points. Only 3 sub-scales were used: Addictive and self-destructive behaviors (9 items; “I have smoked hashish or marijuana”; Cronbach α = .86), Thefts (8 items; “I have stolen, or tried to steal, money or objects such as a cell phone, watch, MP3, etc., from a stranger”; Cronbach α = .91), Violent behaviors (9 items; “I have hit or thrown objects at a teacher or other adult at school”; Cronbach α = .82). It presents adequate indexes of adjustment in the confirmatory factor analysis: CFI = .966, RMR = .034 e RMSEA = .087, χ2(45) = 196, Ratio = 4.35; p = .001.

Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young, 1993, Portuguese adaptation of Felgueiras, 2008).Evaluates the levels of positive psychosocial adaptation when faced with adverse events in life. It is constituted by 25 items that reflect a multidimensional structure with five characteristics of resilience. Only 3 sub-scales were used: Perseverance (6 items; “When I make plans, I take them to the end”; Cronbach α = .83), Self-trust (7 items; “I’m disciplined”; Cronbach α = .78), and Meaning of Life (5 items; “I can get through difficult times because I’ve experienced difficulty before”; Cronbach α = .66). It presents adequate indexes of adjustment in the confirmatory factor analysis: CFI = .860, RMR = .055 e RMSEA = .087, χ2(62) = 334.65, Ratio = 5.3; p = .001.

Procedure

The information for the survey was collected from a demographic and a self-report questionnaire, which was completed by institutionalized adolescents. This research has a cross-sectional nature, and data was collected in the northern and central region of Portugal. The questionnaires were answered within the context of the institution, after each of the directors had been duly informed of the survey and approved the participation of the adolescents. The first contact was established personally and aimed at clarifying any questions there might be as to the procedure and the personal implications to the youth. The youth were given standard instructions and were informed of the general aims of the survey. They were also given instructions as to the completion of the self-report questionnaire, being that confidentiality and anonymity of the answers were totally ensured, as well as the voluntary nature of their collaboration. All participants agreed to participate in the study. The overall response rate was 100 %. Institution’s care directors gave ethical approval for this project. They have been duly informed of the survey and approved the participation of the adolescents. The informed consent was obtained with participants. The study was part of a Post-Doc project approved by the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences—University of Porto.

The order of the questionnaires was randomly inverted so as to avoid biased results, subsequent to exhaustion to fill the same sequence of instruments.

For the statistical analysis of the data obtained, the 17.0 version of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used. In addition to, using the 6.1. version of the EQS program, analyses were also made according to structural equation models. The model presented in this article tests the predictor effect of the quality of the bond to significant figures (teachers and the institution staff) on resilience and deviant behavior among institutionalized adolescents. The model also tests the mediating effect of resilience on the former association using the Sobel test, just as seen on Fig. 1. Sobel test is a method of testing the significance of a mediation effect. In mediation, the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable is hypothesized to be an indirect effect that exists due to the influence of a third variable (the mediator). As a result when the mediator is included in a regression analysis model with the independent variable, the effect of the independent variable is reduced and the effect of the mediator remains significant (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

For this analysis a model was designed which considered the quality of relationship to significant figures (teachers and the institution staff) as predictor of resilience and deviant behavior. In a second step, the mediating effect of resilience was tested. The analysis was developed in accordance to the Sobel test. Analyzing the decomposition effects (through the standardized β value, the error in its standardized value and the probability with a 0.5 significance), the existence of mediation and the presence of indirect effects were observable.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

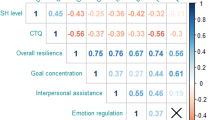

The results of the correlations, averages and standard deviations of the variables studies can be found in Table 2. As expected, the quality of relationship with teachers and institution staff presented significant positive correlations with resilience (r = .353 to r = .428), and significant negative correlations with deviant behaviors (r = −.162 to r = −.201). As we expected the results also point to a significant and negative association between quality of relationship with institution staff and teachers, and deviant behaviors (r = −.181 to r = −.370). To rule out the role of length of institutionalization, we performed also Pearson correlations with all key variables. None of the correlations was significant except addictive/self-destructive behaviour dimension that presented a positive correlation with length of institutionalization (see Table 2).

Age and Gender Differences

In order to assess differences as a function of age of adolescents, two groups (12–14 and 15–18 years old) were created. Multivariate analysis of variance with quality of relationship with significant figures (teachers and institution staff) as dependent variables revealed no significant differences F (2, 197) = .080, p = .923, η2 = .062. Likewise resilience variables (perseverance, self-trust, meaning of life) showed no significant differences as a function of age F (3, 198) = .823, p = .483, η2 = .226. Regarding deviant behaviour (addictive/self-destructive behaviours, theft and violence) MANOVA indicated significant differences F (3, 198) = 3.98, p = .009, η2 = .83. Significant differences were observed for addictive/self-destructive behaviours F (1, 200) = 5:47, p = .020, η2 = .644, where adolescents aged 15–18 presented higher levels of deviant/self-destructive behaviour (M = 2.11 SD = 1.03) compared to adolescents aged 12–14 (M = 1.77, SD = .98).

Bifactorial manovas were performed with age and length of institutionalization as independent factors, in order to inspect whether these dimensions interacted in the prediction of the different variables. The results showed that there were no significant interactions in quality of relationship with significant figures (teachers and institution staff) F (4,388) = .408, p = .803, η2 = .15, in the resilience variables (perseverance, self-trust, meaning of life) F (6,390) = 1.54, p = .164, η2 = .594, and in deviant behaviour F (6,390) = 1.56, p = .159, η2 = .6.

In what concerns gender, multivariate analysis of variance with quality of relationship with significant figures (teachers and institution staff) as dependent variables revealed no significant differences F (2, 197) = .150, p = .861, η2 = .073. Also resilience variables (perseverance, self-trust, meaning of life) showed no significant differences as a function of age F (3, 198) = .826, p = .481, η2 = .227. Regarding deviant behaviour (addictive/self-destructive behaviours, theft and violence), MANOVA indicated significant differences F (3, 198) = 3.61, p = .014, η2 = .79. Addictive/self-destructive behaviour, F (1, 200) = 8.93, p = .003, η2 = .85, was higher for boys (M = 5.69, SD = .66) compared to girls (M = 5.33, SD = 1.1). The same was observed for the theft dimension, F (1, 200) = 9.49, p = .002, η2 = .87 (boys M = 5.27, SD = .87; girls M = 4.8, SD = 1.05) and for the violent behaviors’ dimension F (1, 200) = 7.61, p = .006, η2 = .78 (boys M = 5.47, SD = .81; girls M = 5.1, SD = 1.1).

Again, bifactorial manovas were performed with gender and length of institutionalization as independent factors. The results showed that there were no significant interaction in quality of relationship with significant figures (teachers and institution staff) F (4,388) = 6.38, p = .636, η2 = .21. Resilience variables presented significant values F (6,390) = 3.36, p = .003, η2 = .94. Significant interaction were observed for self-trust F (2, 196) = 5.64, p = .004, η2 = .86, and meaning of life F (2, 196) = 3.37, p = .036, η2 = .63). In both cases girls showed higher values compared to boys, but only for those adolescents who were under institutional care for less time (0–6 months: self-trust—boys M = 3.53, SD = 1.49; girls M = 5.54, SD = 1.1; meaning of life—boys M = 4.10, SD = 1.78; girls M = 5.71, SD = .91). On the contrary boys showed higher values compared to girls when they have been living under institutional care for more than 3 years (self-trust—boys M = 5.16, SD = 1.1; girls M = 5.06, SD = 1.0; meaning of life—boys M = 5.25, SD = 1.18; girls M = 4.99, SD = 1.17). No significant interaction was observed in what concerns deviant behaviour F (6,390) = 1.87, p = .085, η2 = .69.

Associations Between Quality of Relationship to Significant Figures, Resilience and Deviant Behavior

While analyzing the direct results presented in Fig. 2, we observe that the quality of relationship to significant figures is associated with resilience (β = .43, p < .05), as theoretically expected. Besides this, the results revealed that the quality of relationship to significant figures is negatively associated with deviant behavior (β = −.18, p < .05). The model presents indexes of adjustment within critical values (χ2 = 51.69; p = .001; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .09).

Mediating Effect of Resilience on the Previous Association

The 4 main steps of the mediating effect of resilience were analyzed according to the assumptions of the Sobel test. In consonance to the former analyses, the first step reports a negative prediction of the quality of relationship to significant figures in the development of deviant behavior (β = −.20, p < .001). The second step endorses a positive association of the quality of relationship to significant figures with the development of resilience (β = .43, p < .001). The third step of this analysis presents a negative association of resilience with the development of deviant behavior (β = −.30, p < .001) (Table 3). In the last step, all the variables studied in the testing of the model were included, just as theoretically expected, resilience maintains a negative association with the development of deviant behaviors (β = −.28, p < .05), registering a loss of magnitude in the association between the quality of relationship to significant figures and deviant behavior (β = −.006, p > .05). As it is, the analysis in accordance to the Sobel a total mediating effect of resilience (z = −3.39; SE = .033, p = .001; β = −.152) was observed on the association between quality of relationship to significant figures (teachers and institution staff) and deviant behavior (β = −.15 p < .05). The final model presents adequate indexes of adjustment (χ2 = 4.78; p = .001; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .08) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The present study aimed at testing the effect of the quality of relationship of institutionalized adolescents to significant figures (teachers and the institution staff) on the development of deviant behavior. It was also aimed at examining the mediating effect of resilience on the former association.

Age and Gender Differences

First some analyzes were undertaken to better understand the dynamics of the sample in this study. The results pointed to a lack of significant differences in the quality of relationship with significant figures and resilience as a function of age, as well as an absence of gender differences. This first result would not be expected insofar as the younger adolescents tend to be more susceptible and engaging on the care of significant figures, proving to be more vulnerable in the face of adversity (e.g., Masten & Wright, 2010; Munson & McMillen, 2009). Likewise, the absence of gender differences is also unexpected, because girls tend to report more emotional proximity to significant figures, and often higher levels of resilience compared to boys (e.g. Drapeau, Saint-Jacques, Lépine, Bégin, & Bernard, 2007; Hampel & Petermann, 2005). These results may suggest that the construction or strengthening of affective relationships with significant adults can be performed at any stage of adolescence, depending on the emotional and social development of young people, not forgetting the importance of past experiences that tend to constrain involvement in these relationships. This result expresses, as the literature suggests, the importance that is actually providing care and support to young people by these figures, favoring their overall development and a positive adaptation (Hawkins-Rodgers, 2007; Mota & Matos, 2008; Simsek et al., 2007; Zegers, 2007).

On the other hand, some differences were found regarding the development of deviant behaviors (addictive/self-destructive behaviors, theft and violent behaviors). Compared to girls, boys presented higher values in all three variables, and older adolescents reported also a higher frequency of addictive/self-destructive behaviors. This last result may be explained by the greater capacity for autonomy of older adolescents and perhaps a higher involvement with other social and peer contexts that may increase the opportunities for development of risk behaviours (Warr, 2002). The gender differences observed are consistent with previous findings from the general population that suggest that adolescent boys are less tolerant and perceive less control when facing negative events. Boys tend to be more violent and to react more often less adaptively compared to females. Girls seem to deal more positively with similar events whereas boys are more externalizing and tend to develop acting out (e.g. Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002; Zimmermann & Iwanski, 2014).

Analyses with length of institutionalization and gender as independent factors showed an interaction effect in what concerns to resilience. Thus, girls compared to boys reported higher levels of self-trust and meaning of life when entering to institution, However, for those adolescents who are for a longer time at the institution boys present higher resilience as compared to girls. There is little literature able to explain this result; however we can discuss it according to gender differences in coping with adversity. As we discussed before boys are more able to externalize feelings, and also believe in a new relational investment compared with girls, that are more sensitive and more careful with future plans. Future longitudinal research, based on entry cohorts, should attend to differential ways of girls and boys under institutional care developing resilience across time.

Associations Between Quality of Relationship to Significant Figures, Resilience and Deviant Behavior

It was found that the quality of relationship to significant figures is negatively associated with the development of deviant behaviors and positively with the development of resilience. These results are consistent with the qualitative study carried out by Cordovil, Crujo, Vilariça, and Caldeira (2011), as the caregivers and the institutional environment play a fundamental role in the promotion and development of resilience processes. According to these authors, the development of positive relationships allows the awakening of feelings of appreciation and acceptance, which are then expressed in an attitude of perseverance.

Drapeau et al. (2007) recognize that the quality of the bonds of youth in the institutional environment is significant in the growth of resilient youth, namely through the development of feelings of self-efficacy and the adoption of adaptive lives. Through the analysis of case studies, Dalbem and Dell’Aglio (2008) noted that the institution can be a place of new significant affective relationships and therefore helps the development of the resilience process among youth.

Let it be emphasized that the quality of the bond with the teachers is equally important in what concerns the bonds of proximity and affection that the institutionalized youth develop. A relationship of trust established with the teachers seems to prompt increased levels of motivation for academic learning and to reduce aggressive behaviors in children at risk (Wentzel, 2002). Riley (2011) backs up this idea in the sense that the affectionate relationships established with teachers enable the expression and regulation of emotions, increasing adolescents’ self-sufficiency and personal perseverance.

The results also revealed that the quality of relationship to significant figures negatively predicts deviant behavior. The findings pointed to the importance of the creation of a stable emotional environment in the coexistence with the significant figures of affection. Among institutionalized youth vulnerability to risk of infraction seems increased, as emotional discontinuity promotes personal insecurities. In this way, the development of deviant behavior often comes forth as a defensive mechanism which promotes social integration and an increasing sense of belonging to a group, overcoming the feeling of failure in other contexts, specifically when faced with academic failure (Sanches et al., 2012). In adolescence, the risk of developing personal and social problems frequently reflects the difficulty in defending and expressing opinions, in dealing with adverse events, in identifying and resolving interpersonal conflicts and in developing resilience processes (Matos & Spence, 2008).

In this context and according to some authors, when faced with constraints at a social skills level, institutionalized youth often seem to express more aggressive behaviors than youth who live in a family environment (Johnson, Browne, & Hamilton-Giachritsis, 2006). This result is also supported by Dell’Aglio and Siqueira (2010) that concluded that institutionalized children and youth presented higher indicators of experiencing adverse situations, mainly because of the fact that they were taken from their family environment which was marked by abuse, abandonment or negligence comparatively to the participants who lived with their families.

Mediating Effect of Resilience on the Association Between the Quality of Relationship to Significant Figures and Deviant Behavior

Finally, the results indicated a total mediating role of resilience in the association between quality of relationship to significant figures (teachers and institution staff) and deviant behavior. As resilience is a developmental construction intimately related to attachment (Bowlby, 1969), mediation was expected. So part of the variance in the dimension of the quality of relationship to significant figures that explains the avoidance of deviant behaviors seems to be explained by the intervention of resilience. Therefore, these results suggested that not only the teachers but also the institution staff act as protectors toward the development of deviant behaviors, assuming that they encourage the capacity to solve conflicts constructively and that in their relationship to these youth they display a positive attitude towards adversity (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005).

Implications and Practical Recommendations

This study highlights a topic related to the institutionalization process of youth. This issue is rarely approached in the literature, since deviant behaviors are often characterized by society in a pejorative and punishable manner. Little importance is given to the way youth overcome their deviant conducts and develop resilient processes. It is then urgent to intervene in this context and make society aware, governmental bodies in particular, of the importance of ensuring this youth a healthy transition from a negligent context which almost always characterizes the family environment, to an affectionate hosting environment, in which much more is taken into account than basic survival needs. Just as mentioned before, deviant behavior carried out by youth is most of the time the result of a defense mechanism or even of evasion in the face of inner suffering. So only an environment filled with affection and security can overcome the need to transgress in order to “be someone”. The development of an emotionally close and supportive relationship with teachers and institution staff can work as a promoter of adolescents’ personal resources to face up to the demands and challenges of this phase, which is expressed by the development of resilience.

The results of the current study have implications for thinking effective ways to implement the COC plan, stressing the importance of the quality of the relationship with significant figures and caregivers. However we cannot refrain from pointing out the negative aspects present in institutional care, as the difficulty of the institutional staff in understanding and accompanying the institution’s objectives (Ali, Silveira, & Lunardelli, 2004). The staff turnover can be especially problematic if we consider that for close secure relationship to be developed, there is a need for continuity in emotional investment of the caregivers. An adequate number of adults per child and/or adolescent, besides the continuous training seem to be relevant to protect young people from the experience of loss, especially when leaving the institution (Ali et al., 2004; Bazon & Biasoli-Alves, 2000; Shaw, 2006; Yunes et al., 2004). The quality of the physical and structural space in relation to the number of institutionalized young people should also be attended (Ali et al., 2004; Prada & Williams, 2007). Finally, the absence of multidisciplinary composition of the team of professionals (Maricondi, 1997) can reduce the capacity for intervention in specific situations. Social work needs to be emphasized in this context, as these professionals help to make the residential care institution into a developmental and educational context. The points highlighted are connected to the implementation of personal daily routines, meals, schedules and rules, which allow for the creation of internal structure and the recreation of the family environment (Ali et al., 2004); the promotion of vocational opportunities for young people and participation in activities outside the institution (Carvalho, 1993); positive educational practices based on support, understanding, respect and establishment of limits (Prada & Williams, 2007); as well as the preservation of family attachments, keeping siblings together and integration into foster families (Maricondi, 1997; Prada & Williams, 2007).

Limitations and Final Considerations

Although the findings of this study further clarify the role played by teachers and institution staff as significant adults in the lives of institutionalized adolescents, several limitations must be considered when interpreting these results. The present study was limited by its cross-sectional design and by the exclusive use of self-report instruments, susceptible to response and social desirability biases. The causal nature of the conceptual model tested and of our interpretations is based on theoretical propositions. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that adolescents with greater resilience are the ones who are more able to forge strong relationships with adults and avoid development of deviant behaviours. Future research should rely on longitudinal, multi-informant, and multi-method designs, using entry cohorts to control for length of institutionalization. On the other hand, the introduction of a qualitative nature to the present study, more specifically the inclusion of interviews, would be relevant in the sense that it could provide more information not only from the adolescents’ but also from the caregivers’ perspectives.

Notwithstanding the limitations, the study stresses the importance of significant adult figures of affection in the developmental context of institutionalized adolescents, raising the community awareness for investing in the quality of relationships provided to adolescents in institutional care. For this reason, it is fundamental to rethink the way the institutions are managed, directing it toward quality relationships, increasing the number of caregivers, and providing better professional training in order to face the difficulties that arise in this context (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003).

Ethical approval for this project was given by care institutional directors. Institution’s directors had been duly informed of the survey and approved the participation of the adolescents. The study was part of a Post-Doc project approved by the Faculty of Psychology and Education—Porto University.

References

Ali, N. S. A., Silveira, R. S. M., & Lunardelli, M. C. F. (2004). Report of internship experience with monitors who work in a entity that holds childs in risk. In E. Goulard Jr., L. C. Câneo, & M. C. F. Lunardelli (Eds.), Campo de estágio: Espaço de aprendizagem e diversidade (pp. 170–179). Bauru, SP: Joarte.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bazon, M., & Biasoli-Alves, Z. (2000). The transformation of monitors in teachers: A development issue. Psicologia: Reflexão & Crítica, 13, 199–204.

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. London: Penguin.

Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds. London: Routledge.

Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Hattie, J., & Durkin, K. (1999). Adolescent reputation enhancement: Differentiating delinquent, nondelinquent, and at risk youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(4), 593–606. doi:10.1017/S0021963099003807.

Carvalho, M. C. B. (1993). Working with shelters. São Paulo: CBIA.

Cordovil, C., Crujo, M., Vilariça, P., & Caldeira, P. S. (2011). Resilience in institutionalized child and adolescents. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 24, 413–418.

Dalbem, J. X., & Dell’Aglio, D. (2008). Attachment in institutionalized adolescents: Resilience processes in development of new affective bonds. Psico, 39, 33–40.

Damásio, B. F., Borsa, J. C., & Silva, J. P. (2011). 14- Item Resilience Scale (RS- 14): Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 19(3), 131–145.

Dell’Aglio, D. D., & Siqueira, A. C. (2010). Life satisfaction preditors in vulnerability young situations in south of Brasil. Psicologia, Cultura y Sociedade, 9(1), 199–212.

Dishion, T. J., & Kavanagh, K. (2003). Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Drapeau, S., Saint-Jacques, M. C., Lépine, R., Bégin, G., & Bernard, M. (2007). Processes that contribute to resilience among youth in foster care. Journal of Adolescence, 30(6), 977–999. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.01.005.

Emler, N., & Reicher, S. (1995). Adolescence and delinquency—The collective management of reputation. Oxford: Blackwell.

Emler, N., & Reicher, S. (2005). Delinquency: Cause or consequence of social exclusion? In D. Abrams, M. A. Hogg, & J. M. Marques (Eds.), The social psychology of inclusion and exclusion (pp. 211–241). New York: Psychology Press.

Felgueiras, M. C. (2008). Adaptation and validation of resilience scale of Wagnild and Young to Portuguese culture. (Unpublished Master Thesis). Universidade Católica Portuguesa do Porto, Porto.

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419.

Gouveia-Pereira, M., & Carita, A. (2005). Perceptions of justice in school and family context and its relationship to citizenship and deviant behavior (Unpublished manuscript). Instituto Superior de Psicologia Aplicada, Lisboa.

Hampel, P., & Petermann, F. (2005). Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(2), 73–83.

Harland, P., Reijneveld, S. A., Brugman, E., Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P., & Verhulst, F. C. (2002). Family factors and life events as risk factors for behavioral and emotional problems in children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 11, 176–184. doi:10.1007/s00787-002-0277-z.

Hawkins-Rodgers, Y. (2007). Adolescents adjusting to a group home environment: A residential care model of re-organizing attachment behavior and building resiliency. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 1131–1141.

Howard, S., & Johnson, B. (2004). Resilient teachers: Resisting stress and burnout. Social Psychology of Education, 7, 399–420. doi:10.1007/s11218-004-0975-0.

Instituto da Segurança Social, I.P. (2010). Plan for immediate intervention: Report of characterization of children and young people at the reception in 2009 (art. 10. do Capítulo V da Lei n. 31/2003, de 22 de Agosto).

Johnson, R., Browne, K., & Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. (2006). Young children in institutional care at risk of harm. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 7, 1–26. doi:10.1177/1524838005283696.

Junqueira, M. F. P., & Deslandes, S. F. (2003). Resilience and child maltreatment. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 19(1), 227–335.

Kirk, R., & Day, A. (2011). Increasing college access for youth aging out of foster care: Evaluation of a summer camp program for foster youth transitioning from high school to college. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1173–1180. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.02.018.

Lerner, R. M., Walsh, M. E., & Howard, K. A. (1998). Developmental-contextual considerations: Person-context relations as the bases for risk and resiliency in child and adolescent development. In A. S. B. M. Hersen (Ed.), Comprehensive clinical psychology (pp. 1–24). Oxford: Pergamon.

Lindsey, M. A., Browne, D. C., Thompson, R., Hawley, K. M., Graham, J. C., Weisbart, C., et al. (2008). Caregiver mental health, neighborhood, and social network influences on mental health needs among African American children. Social Work Research, 32(2), 79–88.

Loeber, R., Farrington, D., & Petechuck, D. (2003). Child delinquency: Early intervention and prevention. Child delinquency (pp. 3–19). Washington, DC: OJJDP.

Lopez, F. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 283–300. doi:10.1007/s10433-005-0026-5.

Lundman, B., Strandberg, G., Eisemann, M., Gustafson, Y., & Brulin, C. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the resilience scale. Scandinave Journal of Caring Sciences, 21(2), 229–237.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543–562.

Marcotte, G., Marcotte, D., & Bouffard, T. (2002). The influence of familial support and dysfunctional attitudes on depression and delinquency in an adolescent population. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 17(4), 363–376. doi:10.1007/BF03173591.

Maricondi, M. A. (1997). Speaking of shelter: Five years of experience with the project of living houses. São Paulo, SP: Fundação Estadual do Bem Estar do Menor.

Massimo, A., Van Ijzendoor, M. H., Speranza, A. M., & Tambelli, R. (2000). Internal working models of attachment during late childhood and early adolescence: An exploration of stability and change. Attachment and Human Development, 2, 328–346. doi:10.1080/14616730010001587.

Masten, A. S., & Wright, M. O. (2010). Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery, and transformation. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 213–237). New York: The Guilford Press.

Matos, M. G., & Spence, S. (2008). Prevention and positive health in children and adolescents. In M. G. Matos (Ed.), Comunicação, gestão de conflitos e saúde na escola (pp. 56–73). Lisboa: Edições Faculdade de Motricidade Humana.

Mota, C. P., & Matos, P. M. (2005). Relationship to Significant Figures Questionnaire (Unpublished Manuscript). Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação da Universidade do Porto.

Mota, C. P., & Matos, P. M. (2008). Adolescence and institutionalization: An attachment perspective. Psicologia & Sociedade, 20, 367–377.

Mota, C. P., & Matos, P. M. (2010). Institutionalized adolescents: The role of significant figures in the prediction of assertiveness, empathy and self-control. Análise Psicológica, 2, 245–254.

Munson, M. R., & McMillen, J. C. (2009). Natural mentoring and psychosocial outcomes among older youth transitioning from foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 104–111. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.06.003.

Pesce, R. P., Assis, S. G., Santos, N., & Oliveira, R. V. C. (2004). Risk and protection: In search of a promoter balance of resilience. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 20, 135–143.

Poletto, M., & Koller, S. H. (2008). Ecological contexts: Promoters of resilience, risk and protective factors. Estudos de Psicologia, 25, 405–416.

Portzky, M., Wagnild, G., Bacquer, D., & Audenaert, K. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the Dutch Resilience Scale RS-nl on 3265 healthy participants: a confirmation of the association between age and resilience found with the Swedish version. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24, 86–92. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00841.x.

Prada, C. G., & Williams, L. C. A. (2007). Effects of a program of educational practices to monitor a child shelter. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 9, 63–80.

Rebellon, C. (2002). Reconsidering the broken homes - Delinquency relationship and exploring its mediating mechanisms. Criminology, 40(1), 103–136. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125-2002.tb00951.x.

Riley, P. (2011). Attachment theory and the teacher-student relationship (1st ed.). Oxon: Routdlege.

Rutter, M. (2006). The promotion of resilience face of adversity. In A. Clarke & J. Dunn (Eds.), Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development: The Jacobs Foundation series on adolescence (pp. 26–50). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sanches, C., Gouveia-Pereira, M., & Carugati, F. (2012). Justice judgements, school failure and adolescent deviant behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(4), 606–621. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02048.

Sandberg, S., & Rutter, M. (2005). The role of acute life stresses. In M. Rutter & E. Taylor (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (pp. 287–298). Oxford: Blackwell.

Sandler, I. N., Ayers, T. S., Wolchik, S. A., Tein, J. Y., Kwok, O. M., Haine, R. A., …Griffin, W. A. (2003). Family bereavement program: efficacy of a theory-based preventive intervention for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 587–601.

Shaw, T. V. (2006). Reentry into the foster care system after reunification. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 375–1390.

Simsek, Z., Erol, N., Öztop, D., & Munir, K. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of emotional and behavioral problems reported by teachers among institutionally reared children and adolescents in Turkish orphanages compared with community controls. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 883–899. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.01.004.

Siqueira, A. C., Betts, M. K., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2006). Network of social and emotional support for institutionalized adolescents. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 40, 149–158.

Siqueira, A. C., & Dell’Aglio, D. (2006). The impact of institutionalization on children and adolescents: A literature review. Psicologia & Sociedade, 18, 71–80.

Sroufe, L. (1997). Psychopathology as an outcome of development. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 215–268.

Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D., & Helgeson, V. S. (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 2–30. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1.

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1, 165–178.

Warr, M. (2002). Companions in crime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Warr, M. (2005). Making delinquent friends: Adult supervision and children’s affiliations. Criminology, 43(1), 77–106. doi:10.1111/j.0011-1348.2005.00003.x.

Wentzel, K. R. (2002). Are effective teachers like good parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 73, 287–301. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00406.

Yunes, M. A. M., Miranda, A. T., & Cuello, S. E. S. (2004). An ecological look at the risks and opportunities for the development of institutionalized children and adolescents. In S. H. Koller (Ed.). Abordagem ecológica do desenvolvimento humano: Experiencia no Brasil (pp. 193–214). Editora Casa do Psicólogo.

Zegers, M. A. M. (2007). Attachment among institutionalized adolescents: Mental representations, therapeutic relationships and problem behavior (PhD Dissertation). Amsterdam: Vrije Unirsiteit.

Zegers, M. A. M., Schuengel, C., Ijzendoorn, M. H. V., & Janssens, J. M. A. M. (2006). Attachment representations of institutionalized adolescents and their professional caregivers: predicting the development of therapeutic relationships. Journal of Orthosychiatry, 3, 325–334.

Zimmermann, P., & Iwanski, A. (2014). Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 182–194. doi:10.1177/0165025413515405.

Acknowledgment

This research was partially funded by FCT under the project PEst-C/PSI/UI0050/2011 and FEDER funds through the COMPETE program under the Project FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-022714.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mota, C.P., Costa, M. & Matos, P.M. Resilience and Deviant Behavior Among Institutionalized Adolescents: The Relationship with Significant Adults. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 33, 313–325 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0429-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0429-x