Abstract

Protective factors shield young offenders from adversity and stressors, thereby increasing their resilience and reducing their emotional and behavioural problems (EBPs). This chapter investigates a set of external and internal protective factors by examining how they changed over time with EBPs within the EPYC’s sample of young offenders in Singapore. The analyses identified three family-related factors, including family functioning, parental attachment, and home assets, to be effective external protective factors. For internal protective factors, cooperation and communication, and self-efficacy, were identified as two effective buffers. When youths experienced an increase in these factors, their EBPs tended to decrease over time. These findings recommend a strong focus on the family environment in policy making and rehabilitation programmes. Programmes that aim to nurture specific personal competencies could also help to increase resilience for young offenders.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Youths face several potential stressors (e.g., physical conditions, academic problems, as well as peer pressure) in their daily lives (World Health Organization, 2021). If these stressors are not well managed, they can affect the youths’ daily functioning and quality of life; ultimately leading, possibly, to the development of mental health disorders (Thoits, 2013).

However, stressors may not always lead to problematic outcomes. Youths may show resilience when they encounter stressors if they draw on sufficient protective factors (Rutter, 1987; Masten, 2001). Protective factors could buffer youths against adversity and reduce the negative effects of stressors, thus resulting in a lower likelihood of problematic outcomes (O’Connell et al., 2009). These protective factors can be categorised into external or internal assets according to the developmental assets framework (Leffert et al., 1998). External assets refer to health-promoting factors in social settings, whereas internal assets refer to personal attributes (e.g., values, characteristics, and competencies; Leffert et al., 1998). Youths with the most total external and internal assets were found to be the least likely to engage in negative behaviours such as suicidal attempts, violence, and substance use (Leffert et al., 1998; Kingon & O’Sullivan, 2001).

Several protective factors for good youth mental health development have been found in prior studies. Externally, social and family support, neighbourhood and community engagement (Triana et al., 2019, O’Connell et al., 2009), robust social networks and connections (Son et al., 2020), acceptance by parents and peers (Steinhausen & Metzke, 2001), and free psychological help in community (Sharma et al., 2020) were all found to be effective protective factors. For internal factors, high self-esteem (Steinhausen & Metzke, 2001; Triana et al., 2019), self-compassion (Tanaka et al., 2011), emotional self-regulation, good coping skills (Sharma et al., 2020), and problem-solving skills (O’Connell et al., 2009) were found to be important for youth mental health, including young offenders (Li et al., 2021).

Though the research around protective factors is an active industry, few studies have investigated the longitudinal associations between protective factors and emotional and behavioural problems (EBPs). This chapter aims to identify protective factors of various mental health conditions in young offenders as they are particularly vulnerable to EBPs (Rijo et al., 2016). We considered a list of potential protective factors based on past research and examined how these factors changed alongside the EBPs of young offenders over time. Factors that were closely associated with changes in EBPs were more likely to be effective protective factors. Potential protective factors investigated in this chapter include external factors that stem from social relationships and internal factors that stem from an individual’s personal competence. Similar to previous chapters, we explored mental health conditions along two broad dimensions: emotional and behavioural problems. The severity of these EBPs, rather than the presence, is examined in this chapter. By understanding the factors that help youths stay resilient in the face of mental health challenges, the findings in this chapter can aid the development of effective prevention strategies for addressing mental health issues.

7.1 Changes in EBPs, External, and Internal Protective Factors

Before we examined how EBPs and potential protective factors change together over time, we first estimated the individual trajectories of each EBP and potential protective factor over time. We performed latent growth curve modelling (on each variable separately) to estimate these growth trajectories using the longitudinal sample of 835 young offenders. The offenders’ demographics, including their age, sex, and race, were controlled in each model. Intercept factors and slope factors were estimated to represent the trajectories of each variable (e.g., behavioural problems). The intercept factors represent the initial status when the youths first entered the justice system (baseline at Wave 1), and the slope factors represent the linear rates of change from Wave 1 to Wave 3. The latent growth curve models fitted the data well. The intercept and slope factors used to model the trajectories of EBPs, as well as the potential protective factors, are reported in Table 7.1.

7.1.1 EBP Trajectories

As described in Chap. 2, we used the YSR/ASR to measure emotional and behavioural problems. Emotional problems refer to emotional distress within the self, whereas behavioural problems refer to problematic behaviours towards others in the external world (Achenbach, 1991; Bongers et al., 2003). Measures of emotional problems include 29 items, such as “I worry a lot”, and measures of behavioural problems include 27 items, such as “I disobey at school”. Respondents reported how applicable the items were to reflect their conditions of the previous 6 months by rating on three-point scales, from not true (0) and somewhat or sometimes true (1) to very true or often true (2). Their raw scores were further converted to T-scores. Higher scores indicate that the respondent is facing more problems. A T-score of 60 is the borderline clinical score, and a T-score of 64 and above is an indicator of having emotional or behavioural problems within the clinical range (Achenbach, 1991).

Consistent with changes in EBPs, which were reported in Chaps. 4 and 5, we found similar decreasing trends for emotional as well as behavioural problems in our sample of youths who had offended. At baseline, the average T-score of our participants’ emotional problems was 58.34, whereas the average T-score of behavioural problems was 63.46. Considering the cut-off scores for being in the borderline clinical (≥ 60) or the clinical range (≥ 64), our sample started with having emotional problems close to the borderline and behavioural problems close to the clinical range. Over time, the youths’ emotional problems decreased significantly by −2.82 each year on average (p < 0.01), and their behavioural problems decreased significantly by −4.01 each year (p < 0.01), on average. These trends are encouraging as they show that young offenders experienced less EBPs over time after entering the justice system. For the sake of illustration, consider that the average youth has a T-score of 63.46 in behavioural problems at baseline. After 1 year, the average youth’s behavioural T-score falls within the normal range (59.45) and continues to improve to healthier levels in the subsequent year (55.44). That said, the levels of emotional and behavioural problems that plague these young offenders are still much higher than the general population. The LONGSCAN study investigated a sample of 825 non-offender youths in the USA and found an average T-score of 50.0 for emotional problems and 50.1 for behavioural problems (Knight & O’Sullivan, 2001), substantially lower than the current sample. Hence, it is still important to identify effective protective factors that could further alleviate the EBPs of young offenders.

7.1.2 External and Internal Protective Factors’ Trajectories

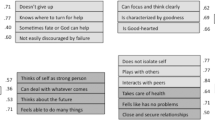

We identified a set of potential external protective factors arising from social relationships across multiple contextual settings, such as family, peer, school, and community. We also identified potential internal protective factors which consist of six facets of personal competence: cooperation and communication, empathy, goal and aspiration, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and self-awareness.

Family-related factors constitute general family functioning, parent attachment, and assets from the home environment. Family functioning refers to the overall quality of interactions amongst family members (Epstein et al., 1978; Minuchin et al., 2009). This construct was measured by 12 items (e.g., “We can express feelings to each other.”) from The McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD; Epstein et al., 1978). The youths rated all items on four-point scales ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4). The scores were reverse coded so higher scores indicate healthier family functioning. Parent attachment, which refers to the youth’s perceptions of their overall attachment with their parents, was assessed by 25 items (e.g., “My mother respects my feelings.”) from the revised Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA). Scores ranged from 1 (almost never or never true) to 5 (almost always or always true). Higher scores imply higher parental attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). Home assets indicate caring and supportive connections, high expectations, and meaningful participation amongst families (Constantine & Benard, 2001).

The other external assets (outside the family context) that we studied include assets from peers, school, and community. Similar to home assets, they indicate the extent of high-quality connections, expectations, and interactions that the youth has within each social context. These assets were measured by the Resilience and Youth Development Module (RYDM); see a summary of items for each construct in Chap. 2. A four-point scale ranging from not at all true (1) to very much true (4) was adopted for each item. Higher scores imply that the respondent has more protective assets.

For internal factors, we investigated assets that arise from the youth’s personal competence which include cooperation and communication, empathy, goal and aspiration, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and self-awareness. These internal assets refer to individual qualities, strengths, and characteristics linked with desirable developmental outcomes (Constantine & Benard, 2001). Cooperation and communication refers to social competence; empathy refers to understanding and caring about another’s feelings; goals and aspirations refers to having dreams, visions, and plans towards the future; problem-solving refers to the ability to plan and think thoroughly before making a decision or taking action; and self-efficacy refers to the belief in one’s ability to do something, whereas self-awareness refers to knowing and understanding one’s self (Constantine & Benard, 2001). Similar to the external assets, these internal assets were measured by the RYDM. Higher scores imply that the respondent has more protective assets.

Overall, our results revealed that almost all of these factors, both internal and external, improved over time on average. This improving trend can be observed from the negative slopes of EBPs and the positive slopes of protective factors (see Table 7.1). These overall desirable changes in mental health, social relationships, and personal competence of young offenders are encouraging from a rehabilitative perspective. The justice system aims to provide treatment for these youths so that they will have healthy outcomes, such as the successful reintegration into society, when they exit the justice system (Steinberg et al., 2004). Such treatments improve the psychosocial development of young offenders which translates into positive outcomes (Steinberg et al., 2004). Singapore, in particular, offers many rehabilitation programmes for young offenders to address the offenders’ criminogenic thinking and behaviour, improve their prosocial skills, and incorporate maximum participation of their families and the community (Kamal, 2006).

Despite these overall positive trends, we found significant variations in the change patterns, implying that individuals differed in their rates of change (Farrington et al., 1988; Steinberg et al., 2004). Furthermore, the average improvements in peer assets, school assets, and cooperation and communication amongst young offenders were not significant. A likely explanation is that some social interactions of these youths are placed under restrictions and scrutiny within the justice system. They might not have been able to socially adapt to these changes, which suggests that there might be a need to implement programmes to orientate their social skills or facilitate their social interactions. We also found that their average goals and aspirations decreased after entering the justice system. Arguably, entering the justice system could affect the orientation towards their future for some youth (Steinberg et al., 2004). Offence charges, sanctions, and early criminal labelling may take away the eligibility of various careers for these young offenders (Oyserman & Markus, 1990; Moffitt, 2017). Thus, their views of their “possible selves” and aspirations towards the future might be impaired, which explains the decreasing goals and aspirations found in our study. In the next section, we will further explore the effects of protective factors whilst accounting for the different change patterns.

7.2 Identifying Effective Protective Factors

As mentioned earlier, our main strategy to identify effective protective factors involves covarying the trajectories of the factors with the trajectories of emotional and behavioural problems. Assuming that an asset (e.g., home assets) is indeed a protective factor that guards young offenders from mental distress, we should see these variables covarying closely with one another across time. If a youth experiences an improvement in the asset, this should increase their resilience against mental health distress, leading to less emotional and/or behavioural problems. Conversely, if a youth experiences a decrease in the asset, we should expect them to be less able to cope with mental health difficulties and experience more emotional and/or behavioural problems. Corresponding changes will indicate that intervening and improving the identified protective factors can help reduce EBPs.

Since we have already estimated the individual trajectories of each variable (represented by their respective intercepts and slopes), we further conducted fully multivariate latent growth curve models to assess which factors’ trajectories significantly predict the intercept and slope of EBPs. In the model, we simultaneously estimated a trajectory for the protective factor and EBPs to represent their changes over time. The standardised coefficients representing the associations between the trajectories of each factor and the youths’ EBPs are summarised in Table 7.2. “I(A) to I(B)” represents the association between the two variables at baseline. “I(A) to S(B)” can be interpreted as the relationship between the factor at baseline and the changes in EBPs over time. This chapter is especially interested in the last coefficient, “S(A) to S(B)”, which is the relationship between the slopes of the two variables. This reflects how changes in the factor affect changes in EBPs, which is useful for identifying effective protective factors. This yields good evidence of causal effects, since a key requirement for causality is that changes in the cause predict changes in its effect. Importantly, our analyses also study the within-individual changes in protective factors and EBPs (as opposed to between-individual changes). This accounts for many extraneous variables that would confound our causal interpretations. Three controlling variables, indexing the participants’ age, sex, and race, were added to the models. In the remainder of this section, we highlight our key findings from this analysis and discuss the effectiveness of the studied factors.

7.2.1 External Protective Factors: Family Context

A person’s psychological well-being develops through interactions with other people in their proximal environments (Zhang et al., 2011). The family, being the most direct and recent microenvironment for youths, is pivotal to the development of their psychological well-being (Zeleke, 2013). Various constructs related to family have been consistently found to protect youths from mental health problems, including family functioning (Yang et al., 2014; Milburn et al., 2019), family support (Seidman et al., 1999; Symister & Friend, 2003), family cohesion (Van Dijk et al., 2014; Jhang, 2017), positive family communication (Carbonell et al., 1998; Thoits, 2013), and parenting involvement in schools (Richman et al., 1998). The findings all point to the family being a crucial influence on healthy youth development. Families care for each other, help each other, provide advice, and regulate each other’s behaviours (Cohen, 2004; Reczek et al., 2014; Jhang, 2017). Good relationships and support amongst family members contribute to (a) the development of better interpersonal skills, self confidence, and greater sense of purpose, (b) the feeling of love and acceptance, as well as (c) better coping of stress and depression (e.g., Demir et al., 2011; Graziano et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014).

Consistent with this, we found that family-related variables provide stable and strong buffering effects against EBPs. Results showed that at baseline, youths who had better family functioning, higher parent attachment, and better home assets had less EBPs. Youths with better baseline family assets were also more likely to experience stronger improvement in emotional problems (but not behavioural problems) over time.

Of special interest, we found that changes in family functioning, parent attachment, and home assets all had significant and positive effects on changes in emotional and behavioural problems. Improving these three family-related factors corresponded with more decrease in EBPs over time. To get an intuitive understanding of these effects, we compared the EBPs of youths experiencing three different trends of family-related protective factors over time: (1) youths who had above average change (+1 SD above average), (2) average change, and (3) below average change (−1 SD below average) in family-related factors. We can visualise how these three groups differentially change in EBPs over time in Figs. 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3 (one figure for each of the family-related factors). When there is an average improvement in family-related factors, there is typically a moderate decrease in EBPs over time. For those with above average improvement in these family-related factors, we observe a sharper decrease in EBPs over time. Finally, with below average improvement in family-related factors, we tend to see a maintained or moderately increased EBPs over time.

We can quantify these effects by comparing the EBPs of youths who experienced high improvement in family-related factors (+1 SD above the average change) against the youths with average change. Firstly, for family functioning, the youths with average change experienced an average decrease of −2.42 per year in their T-score of emotional problems and an average decrease of −3.66 per year in behavioural problems. In contrast, youths with high improvement in family functioning (represented by the above average change group) experienced roughly a three times sharper decrease (−7.26 per year) in emotional problems and a 2.2 times sharper decrease (−8.05 per year) in behavioural problems over time compared to the youths with average change in family functioning. Moving onto the other family-related factors, youths who had high improvement in parent attachment experienced a 2.6 times greater decrease in emotional problems and a two times greater decrease in behavioural problems over time compared to youths with an average improvement in parent attachment. Further analyses were conducted to examine whether the effects of parent attachment differ between attachment to mothers and fathers. We did not find a significant difference in their effects on EBPs. Developing higher attachment to either mothers or fathers both helped to reduce EBPs over time. As for home assets, high improvement brought about a 2.7 times greater decrease in emotional problems and a 2.1 times greater decrease in behavioural problems compared to the average improvement. All these effects were significant at the p < 0.01 level and the coefficients are summarized in Table 7.2.

7.2.2 External Protective Factors: Assets from Peer Groups, School, and Community Settings

Outside of the family setting, other social contexts like peer groups, school, and community settings may also aid youths in their prosocial development (Graber et al., 2018). Each of these contexts provides rich activities and social interactions. They may accentuate social support, compensate for unhealthy family relationships, deter youths from antisocial behaviour in the presence of normative pressures, provide positive role models (e.g., prosocial peers, teachers), and develop self-competence and interpersonal functioning (Dray et al., 2017; Larson, 2000; Brown, 2004; Steinberg et al., 2004).

Accordingly, we explored whether assets from peer relationships, school environment, and community environment of young offenders affect their EBPs. We found that, at baseline, youths with higher peer assets had less behavioural problems, but not emotional problems. School or community assets did not correlate with either emotional or behavioural problems at baseline. Furthermore, all three of these assets did not significantly predict how emotional and behavioural problems change over time. A possible reason is that the protective effects of these factors might have been indirect and moderated by other factors. For example, Li et al. (2021) found buffering effects from peer assets and school/work assets against certain types of adversities, such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse. Future work can test if these buffering effects interact with the type of adversities faced by the youths or other risk factors. Whilst there is still merit in exploring the potential protective effects of peer relationships, school environment, and community environment, our findings further highlight the importance of the family setting, which had a more direct and stable effect over time on the mental health of young offenders. This also echoes the finding in Chap. 4, where family assets were identified as the most prominent protective factor against depression. These converging results make a strong call for intervention programmes to target the family unit in their efforts to safeguard the external environments of young offenders.

7.2.3 Internal Protective Factors: Personal Competence

For internal factors, we investigated the effectiveness of six facets of personal competence: cooperation and communication, empathy, goal and aspiration, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and self-awareness as protective factors. There is a wealth of recent studies showing that these factors promote resilience and reduce mental health problems in youths (Dray et al., 2017, Beyond Blue, 2018; Masten, 2021). Here, we assessed the extent in which these factors covary with EBPs across time on our longitudinal sample of young offenders.

Results showed that cooperation and communication and self-efficacy were the most significant protective factors associated with decreased EBPs. At baseline, youths with higher cooperation and communication experienced less emotional and behavioural problems. Youths with higher self-efficacy had less emotional but not behavioural problems at baseline. Of interest, a higher increase in cooperation and communication and self-efficacy also significantly predicted a sharper decrease in EBPs over time. As before, we can compare youths with high improvement (above average change) in these internal assets against youths with average improvement to quantify the protective effects of these internal assets. Youths who had high improvement in cooperation and communication over time tended to experience a sharper decrease, roughly a 3.1 times greater decrease in emotional problems and a 2.1 times greater decrease in behavioural problems over time compared to youths who had an average change in cooperation and communication. Youths who had high improvement in self-efficacy over time also tended to experience roughly a three times greater decrease in emotional problems and a 1.7 times greater decrease in behavioural problems compared to youths with average improvement. The coefficients are summarized in Table 7.2, and these effects can be visualised in Figs. 7.4 and 7.5. The figures visually show that youths with above average change in cooperation and communication, and self-efficacy experienced the most decrease in EBPs over time (represented by the blue line with a diamond in Figs. 7.4 and 7.5) compared with youths with average or below average change.

Good cooperation and communication indicate higher social competence and prosocial skills, which promote interpersonal functioning. Well-functioning social interactions can guard against mental health distress and related mental illnesses (Dray et al., 2017). Meanwhile, increased self-efficacy involves higher self-esteem and more positive views of oneself (Fukukawa et al., 2000). Self-esteem, in turn, is an important psychological resource that people draw on to maintain optimism and increase positive affect, making it an effective buffer against mental health distress (Symister & Friend, 2003).

As for other internal factors, in terms of their dynamic changes with EBPs, we found that an increase in problem-solving and self-awareness predicted a decrease in emotional problems, but not behavioural problems. As discussed before, emotional problems concern emotional distress within the self, whereas behavioural problems concern behavioural conflicts with the external world (Achenbach, 1991; Bongers et al., 2003). Improved problem-solving will enhance personal planning and thinking capabilities towards an individual’s decision-making, and improved self-awareness contributes to better understanding of oneself (Constantine & Benard, 2001). Both assets help to reduce personal distress and internal conflict.

7.3 Summary

This chapter showed that in young offenders, improvement in family functioning, parent attachment, home assets, cooperation and communication, and self-efficacy all grant protection against EBPs in the long run. Better self-awareness and problem-solving help these youths bounce back from emotional problems but not behavioural problems. Peer assets, school assets and community assets, goals and aspirations, and empathy were not found to have direct protective effects against EBPs amongst these youths. These findings refine our understanding of how internal and external protective factors relate to EBPs in young offenders.

Young offenders and non-offending youth have different treatment needs, especially so across different cultural contexts (Lai et al., 2016; Koh, et al., 2021). Identifying effective protective factors specific to these youths in Singapore can inform correctional agencies on precise areas for focused intervention (Hoge & Andrews, 2010). As a collectivist society, Singapore values family and family obligations, making family support an especially important factor to maintain mental health compared to individualistic cultures (Berkman et al., 2000; Koh, et al., 2021). Past research in Singapore also found Functional Family Therapy (FFT) to be effective for young offenders. Individuals who received FFT reported higher levels of well-being immediately and up to the end of their probation periods compared with those who did not (Gan et al., 2021). In line with this discussion, our findings show the dynamic relationship between family-related factors and EBPs. Youths who improved more in family-related factors tended to also decrease more in EBPs over time. These results theoretically support the need to implement family-based intervention on a larger scale and increase parental involvement in intervention programmes for young offenders. Such interventions could work on various facets of the family, including increasing understanding, supportiveness, openness, acceptance, belongingness, and meaningful activities within the family context.

Internally, the findings highlighted the need to include personal capabilities into treatment planning. Current cognitive interventions in Singapore include problem-solving, conflict resolution, responsible thinking, and self-control (Kamal, 2006; Koh et al., 2021; Ministry of Social and Family Development, 2022). Our findings recommend incorporating more physical activities, mindful processes, counselling, and therapy sessions (e.g., CBT) to improve individuals’ self-efficacy and self-awareness (Williams & French, 2011). Apart from self-efficacy, we also identified cooperation and communication as a strong protective factor. Yet, it is also one of the few protective factors that remained unchanged, on average, in youths within the justice system. This signals a strong need to provide training for young offenders in areas such as enhancing their interpersonal skills (e.g., Lipsey, 2000). In sum, this chapter meaningfully adds to the evidence base for resilience-focused interventions which build supportive social structures or personal improvement programmes for youth.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 16(5), 427–454.

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 51(6), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4

Blue, B. (2018). Building resilience in children aged 0–12-A practice guide. Beyond Blue, 2017.

Bongers, I. L., Koot, H. M., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.179

Brown, B. B. (2004). Adolescents’ relationships with peers. Handbook of adolescent psychology, 363–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch12

Carbonell, D. M., Reinherz, H. Z., & Giaconia, R. M. (1998). Risk and resilience in late adolescence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 15, 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025107827111

Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American psychologist, 59(8), 676. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

Constantine, N. A., & Benard, B. (2001). California healthy kids survey resilience assessment module: Technical report. Journal of Adolescent Health, 28(2), 122–140.

Demir, T., Karacetin, G., Demir, D. E., & Uysal, O. (2011). Epidemiology of depression in an urban population of Turkish children and adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 134(1–3), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.041

Dray, J., Bowman, J., Campbell, E., Freund, M., Wolfenden, L., Hodder, R. K., McElwaine, K., Tremain, D., Bartlem, K., Bailey, J., Small, T., Palazzi, K., Oldmeadow, C., & Wiggers, J. (2017). Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(10), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780

Epstein, N. B., Bishop, D. S., & Levin, S. (1978). The McMaster model of family functioning. Journal of Marital and Family therapy, 4(4), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1978.tb00537.x

Farrington, D. P., Gallagher, B., Morley, L., St Ledger, R. J., & West, D. J. (1988). Are there any successful men from criminogenic backgrounds? Psychiatry, 51(2), 116–130.

Fukukawa, Y., Tsuboi, S., Niino, N., Ando, F., Kosugi, S., & Shimokata, H. (2000). Effects of social support and self-esteem on depressive symptoms in Japanese middle-aged and elderly people. Journal of epidemiology, 10(1sup), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.10.1sup_63

Gan, D. Z., Zhou, Y., Abdul Wahab, N. D. B., Ruby, K., & Hoo, E. (2021). Effectiveness of functional family therapy in a non-western context: Findings from a randomized-controlled evaluation of youth offenders in Singapore. Family Process, 60(4), 1170–1184. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12630

Graber, J. A., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Petersen, A. C. (Eds.). (2018). Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Psychology Press.

Graziano, F., Bonino, S., & Cattelino, E. (2009). Links between maternal and paternal support, depressive feelings and social and academic self-efficacy in adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6(2), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620701252066

Hoge, R. D., & Andrews, D. A. (2010). Evaluation for risk of violence in Juveniles. Oxford University Press.

Jhang, F. H. (2017). Economically disadvantaged adolescents’ self-concept and academic achievement as mediators between family cohesion and mental health in Taiwan. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15, 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9737-z

Kamal, C. (2006). The probation service in Singapore. 127TH International training course visiting experts’ papers, Resource material series, p. 67.

Kingon, Y. S., & O’Sullivan, A. L. (2001). The family as a protective asset in adolescent development. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 19(2), 102–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/089801010101900202

Koh, L. L., Day, A., Klettke, B., Daffern, M., & Chu, C. M. (2021). An exploration of risk and protective characteristics of violent youth offenders in Singapore across adolescent developmental stages. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 20(4), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2021.1886203

Lai, V., Zeng, G., & Chu, C. M. (2016). Violent and nonviolent youth offenders: Preliminary evidence on group subtypes. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 14(3), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204015615193

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

Leffert, N., Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., Sharma, A. R., Drake, D. R., & Blyth, D. A. (1998). Developmental assets: Measurement and prediction of risk behaviors among adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 2(4), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0204_4

Li, D., Ng, N., Chu, C. M., Oei, A., Chng, G., & Ruby, K. (2021). Child maltreatment and protective assets in the development of internalising and externalising problems: A study of youth offenders. Journal of Adolescence, 91, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.07.002

Lipsey, M. W. (2000). Effective intervention for serious juvenile offenders. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227

Masten, A. S. (2021). Resilience of children in disasters: A multisystem perspective. International Journal of Psychology, 56(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12737

Milburn, N. G., Stein, J. A., Lopez, S. A., Hilberg, A. M., Veprinsky, A., Arnold, E. M., ... & Comulada, W. S. (2019). Trauma, family factors and the mental health of homeless adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12, 37–47.

Ministry of Social and Family Development. (2022). https://www.msf.gov.sg/policies/Rehabilitation-of-Offenders/Community-based-Rehabilitation/Probation-Order/Probation-Programmes/Pages/Probation-Core-Programmes.aspx

Minuchin, S., Rosman, B. L., Baker, L., & Minuchin, S. (2009). Psychosomatic families: Anorexia nervosa in context. Harvard University Press.

Moffitt, T. E. (2017). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy (pp. 69–96). Routledge.

O’Connell, M. E., Boat, T., & Warner, K. E. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. National Academy Press.

Oyserman, D., & Markus, H. R. (1990). Possible selves and delinquency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(1), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.112

Reczek, C. (2014). Conducting a multi family member interview study. Family process, 53(2), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12060

Richman, J. M., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Bowen, G. L. (1998). Social support for adolescents at risk of school failure. Social Work, 43(4), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/43.4.309

Rijo, D., Brazão, N., Barroso, R., da Silva, D. R., Vagos, P., Vieira, A., Lavado, A., & Macedo, A. M. (2016). Mental health problems in male young offenders in custodial versus community based-programs: Implications for juvenile justice interventions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10, 40.

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(3), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x

Seidman, E., Chesir-Teran, D., Friedman, J. L., Yoshikawa, H., Allen, L., Roberts, A., & Aber, J. L. (1999). The risk and protective functions of perceived family and peer microsystems among urban adolescents in poverty. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022835717964

Sharma, V., Ortiz, M. R., & Sharma, N. (2020). Risk and protective factors for adolescent and young adult mental health within the context of COVID-19: A perspective from Nepal. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(1), 135–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.006

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

Steinberg, L., Chung, H. L., & Little, M. (2004). Reentry of young offenders from the justice system: A developmental perspective. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204003260045

Steinhausen, H. C., & Metzke, C. W. (2001). Risk, compensatory, vulnerability, and protective factors influencing mental health in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(3), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010471210790

Symister, P., & Friend, R. (2003). The influence of social support and problematic support on optimism and depression in chronic illness: a prospective study evaluating self-esteem as a mediator. Health psychology, 22(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.123

Tanaka, M., Wekerle, C., Schmuck, M. L., Paglia-Boak, A., & MAP Research Team. (2011). The linkages among childhood maltreatment, adolescent mental health, and self-compassion in child welfare adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(10), 887–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.003

Thoits, P. A. (2013). Self, identity, stress, and mental health. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 357–377). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_18

Triana, R., Keliat, B. A., & Sulistiowati, N. M. D. (2019). The relationship between self-esteem, family relationships and social support as the protective factors and adolescent mental health. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 7(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2019.715

Van Dijk, M. P., Branje, S., Keijsers, L., Hawk, S. T., Hale, W. W., & Meeus, W. (2014). Self-concept clarity across adolescence: Longitudinal associations with open communication with parents and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1861–1876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0055-x

Wang, P. W., Liu, T. L., Ko, C. H., Lin, H. C., Huang, M. F., Yeh, Y. C., & Yen, C. F. (2014). Association between problematic cellular phone use and suicide: The moderating effect of family function and depression. Comprehensive psychiatry, 55(2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.09.006

Williams, S. L., & French, D. P. (2011). What are the most effective intervention techniques for changing physical activity self-efficacy and physical activity behaviour—And are they the same? Health Education Research, 26(2), 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr005

World Health Organization. (2021). Adolescent mental health [Fact sheet]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

Yang, H. J., Wu, J. Y., Huang, S. S., Lien, M. H., & Lee, T. S. H. (2014). Perceived discrimination, family functioning, and depressive symptoms among immigrant women in Taiwan. Archives of women’s mental health, 17, 359–366.

Zhang, D.-J., Wang, J.-L., & Yu, L. (Eds.). (2011). Methods and implementary strategies on cultivating students’ psychological suzhi. Nova Science Publishers.

Zeleke, W. A. (2013). Psychological adjustment and relational development in Ethiopian adoptees and their families. University of Montana.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Liu, M., Teo, D., Chu, C.M. (2023). Protective Factors Against Emotional and Behavioural Problems in Young Offenders. In: Li, D., Chu, C.M., Farrington, D.P. (eds) Emotional and Behavioural Problems of Young Offenders in Singapore. SpringerBriefs in Criminology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41702-3_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41702-3_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-41701-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-41702-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)