Abstract

This study examined: (1) the relationship of familial factors to Latina adolescents’ depressive symptomology and, (2) the mediating role of parental connectedness in the relationships between perceived parental caring, academic interest and depression. The sample consisted of 276 Latina adolescents taken from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). A path model was hypothesized to illustrate the direct and indirect relationships between adolescent perceived mother connectedness, father connectedness, parental caring, parental academic interest, and depression. The hypothesized path model had good model fit: χ 2 (3, 224) = 6.53, p = .08; χ 2/df = 2.18; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; and RMSEA = .07. In addition, father connectedness was found to mediate the relationship between general caring and depression as well as academic interest and depressive symptoms. Mother connectedness mediated the relationship between general caring and depressive symptoms. Consideration of Latina adolescents’ perceived parent–child relationship is of particular salience when working with depressed Latinas. Findings will be discussed for intervention and prevention efforts for Latina teens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Latina adolescents frequently report higher levels of depressive symptoms and psychological distress than Latino boys and girls from other ethnic groups (Céspedes and Huey 2008). Although this disparity exists, little is known about the contributing factors to increased rates of depressive symptomology for this population. Framing Latina adolescent depressive symptoms within a resiliency framework allows researchers to understand both risk and protective resources despite other challenges this group may face (Rew et al. 2001). Previous research has found that positive family relations (e.g., caring, connectedness, and effective communication) are protective resources against negative mental health outcomes for Latina adolescents. The absence of positive familial factors introduces considerable risk for the mental health of adolescents (Resnick 2000). Thus, the current study was designed to present and test a model of familial factors that may contribute to the depressive symptoms of Latina adolescents. Namely, we examine the role of perceived parental caring, parental interest in the child’s academic life, and adolescent’s connectedness with her mother and father on depressive symptoms.

Familismo is a Latina/o cultural value whereby unity and interconnectedness with family members are held in esteem (Santiago-Rivera 2003). Familismo is passed on to children from parents and others and often has gender differential manifestations. For example, Latina girls may be taught that her role in the family is to maintain harmony and attend to the needs of her father and brothers (i.e., marianismo). This may manifest itself through taking care of various household duties and silencing her needs in order to keep peace within the household (Castillo et al. 2010; Piña-Watson et al. 2014). Conversely, the same value of family may be communicated to Latino boys by expecting sons to uphold the honor of the family and serve as protectors, especially to sisters and the mother.

Family connectedness has been conceptualized as the perceived extent to which a family member cares for, understands, and communicates about issues that are important to the individual (i.e., school and interpersonal relationships; Garcia et al. 2008; Zayas et al. 2009). When a Latina feels cared for and connected with her parents, she has better mental health outcomes (Turner et al. 2002; Zayas et al. 2000, 2005). Conversely, when she experiences high levels of family conflict, she can suffer from higher levels of distress, depressive symptoms, and suicidality (Garcia et al. 2008; Kobus and Reyes 2000; Piña-Watson et al. 2013). For example, a study by Garcia et al. (2008) found that when Latina adolescents had high levels of perceived caring and connectedness with family, they reported lower levels of distress. Conversely, Piña-Watson et al. (2013) found that when Latinas expressed higher levels of family conflict, they reported higher levels of distress. Further, scholars have noted that the presence of a supportive family may operate as a buffer against depression and suicide (Chance et al. 1998). These findings can be explained within the cultural value of familismo.

Much of the research on parent–child relationships centers on general measures of connection and care, and it does not take into account specific areas of care such as academics (Ackard et al. 2006; Garcia et al. 2008). Although caring about the child’s general well-being is important for the parent–child relationship, a more nuanced examination of the presence of care for areas such as academics could be salient in determining how connected youth feel with parents. Latinas spend a large proportion of their weekdays in school. When parents show their children that they are interested in both the child’s personal and academic well-being, positive outcomes can occur. For example, research has shown that when adolescents perceive parents to be caring and concerned about their academic achievement, they demonstrate increased levels of motivation and overall student success (Mombourquette 2007). As such, the current study seeks to fill this gap in the literature through investigating the role of both dimensions of care on the parent child relationship (connectedness) and mental health (depressive symptoms).

Further, few studies have examined the influence of caregiver specific relationships on the mental health of Latinas (i.e., mother–daughter and father–daughter relationships). When this has been investigated, the focus is usually on the relationship with the mother (Rastogi and Wampler 1999). For example, in a study with Latina adolescents and mothers, Zayas et al. (2000) found that mother–daughter mutuality, defined as reciprocal empathy and engagement between the mother and daughter, is a protective resource in preventing suicidality. In another study of Latina adolescent suicide, those who attempted suicide reported lower levels of mother–daughter connectedness than those who had not (Turner et al. 2002). Additionally, another study found that a Latina adolescent’s perceived relationship quality with her mother separated suicide attempters from non-attempters (Zayas et al. 2009). In reference to depression, Ackard et al. (2006) found that nearly 64 % of girls who reported that mothers cared “very little” suffered from depression. This rate is nearly double that of boys who reported that mothers cared “very little.”

In the depression literature, little is known about the impact of the father–daughter relationship. Scholars have noted the potential importance of understanding this relationship and the connection to mental health outcomes (Gulbas et al. 2011; Zayas et al. 2005). For example, Gulbas et al. (2011) called for future research to focus attention on two-parent families. They proposed this would provide insight into the role that Latino fathers play in mental health outcomes. Additionally, Zayas et al. (2005) highlighted the scarcity of literature with a focus on the father’s contribution to mental health outcomes and the necessity to examine this relationship in order to understand the complexity of family dynamics for Latinas.

Purpose and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study is to determine the role of various familial factors on Latina adolescent depressive symptomology. Given the importance placed on connectedness with family members in the Latina/o culture through the value of familismo and previous research that connects parental caring and connectedness to mental health outcomes, this study proposes a model that accounts for depressive symptoms of Latina adolescents. Specifically, the hypotheses of this study are: (a) perceived caring and academic interest will be positively correlated; (b) higher perceived caring will predict higher perceived mother and father connectedness; (c) higher academic interest will predict higher perceived mother and father connectedness; (d) higher perceived mother and father connectedness will predict lower depressive symptoms; (e) mother connectedness and father connectedness will serve as mediators between academic interest-depression and caring-depression relationships. These hypotheses will be tested using a path analysis.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) is a longitudinal study that examined a school-based cohort of students that is nationally representative of public and private high schools in the United States. The Add Health study was conducted in four waves from the years 1994 through 2009. Our study analyzed data from Wave 1 since this was the time period when the sample was in the adolescent age range (1994–1995). This wave consisted of 20,745 adolescents from 7th through 12th grade. For this study, eligible participants met the following inclusion criteria: female of Latin descent, between the age of 13–18, and reported having both a mother and father figure present in her life. Participants who did not meet all of these criteria were excluded from consideration. Using listwise deletion, two cases were deleted due to having missing data. This left a final sample of 276 participants.

The 276 participants in the current study ranged from 13 to 18 years of age (M = 15.76; SD = 1.6). The majority of the participants reported that English was the primary language spoken within the home (54 %) and were of Mexican descent (56 %). Other ethnic groups represented in the sample were: Puerto Rican (14 %), Central/South American (11 %), Cuban (5 %), and Chicano (6 %).

Measures

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depressive Symptoms Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977) was utilized to measure symptoms of depression. Items asked questions about the frequency of depressive symptoms that the participant experienced in the past week with responses ranging from 0 (Never or rarely) to 3 (Most or all of the time). A sample item is “You felt that you could not shake off the blues even with help from your family and friends.” Four items were reversed scored. The sum of the 20 items ranged from 0 to 57 with higher scores indicative of higher frequencies of depressive symptoms experienced in the past week. For the current sample, this measure had acceptable internal consistency (α = .86).

Mother Connectedness

Six items were summed to create a mother connectedness scale. Items asked questions about how close the participant feels to her mother. A sample item is “When you do something wrong that is important, your mother talks about it with you and helps you understand why it is wrong.” The sum of the items ranged from 6 to 30 with higher scores indicative of higher perceived connectedness. For the current sample, this measure had an acceptable internal consistency (α = .85).

Father Connectedness

Four items were summed to create a father connectedness scale. Items asked questions about how close the participant feels to her father. A sample item is “How close do you feel to your father?” The sum of the items ranged from 4 to 20 with higher scores indicative of higher perceived connectedness. For the current sample, this measure had acceptable internal consistency (α = .83).

Caring

Three items were summed to create a parental caring scale. Items asked questions about participant’s perception of how much her parents care for her. A sample item is “How much do you feel your parents care about you?” The sum of the 3 items ranged from 3 to 15 with higher scores indicative of higher perceived parental caring. For the current sample, this measure had acceptable internal consistency (α = .76).

Academic Interest

Four items were summed to create a parental academic interest scale. Items asked questions about the participant’s perception of whether her parents demonstrated an interest in her academic work. A sample item is “[You] talked about your school work or grades.” The sum of the items ranged from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicative of higher perceived parental academic interest. For the current sample, this measure had acceptable internal consistency (α = .67).

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using MPlus Version 7. Descriptive statistics including frequencies, means, and standard deviations were conducted. In addition, a path analysis, including bootstrapping, was conducted to test the hypothesized model that include the direct and indirect relationships between caring, academic interest, mother connectedness, father connectedness, and depression.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The data met statistical assumptions for multivariate normality, linearity, and multicollinearity. Table 1 illustrates Pearson’s product moment correlations between these five variables, as well as means, standard deviations, and alphas for each measure.

Main Analyses

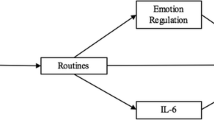

The model, indicated in Fig. 1, represents the proposed hypotheses. A path analysis based on robust maximum likelihood procedures was conducted to test the fit of the hypothesized model. Previous literature has suggested that the model fit be evaluated by the following criteria (Hu and Bentler 1999; Kline 2005; Loehlin 1998; Weston and Gore 2006): a Chi squared (χ 2) that is non-significant at the p < .05 level, a Chi squared to degrees of freedom ratio (χ 2/df) < 3.0; comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .90; a Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ .95; and a root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) < .08. According to these indices, the hypothesized model resulted in good model fit: χ 2 (3, 224) = 6.53, p = .08; χ 2/df = 2.18; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; and RMSEA = .07. For these direct paths in the model, general perceived caring and academic interest are significantly correlated (r = .35, p = .000). Additionally, general perceived caring significantly and positively predicts both mother (B = 1.06; SE = .12; p = .000) and father connectedness (B = .46; SE = .14; p = .001). Perceived parental academic interest significantly and positively predicts father connectedness (B = .99; SE = .13; p = .000), but not mother connectedness (B = −.05; SE = .11; p = .68). Finally, both mother (B = −.31 SE = .08; p = .000) and father connectedness (B = −.34; SE = .11; p = .001) significantly and negatively predict depressive symptoms for Latina adolescents. Figure 1 represents the hypothesized and tested model with the unstandardized weights, standard errors, and p values.

Hypothesized and tested path model. Unstandardized estimates reported with standard errors reported in parentheses; statistically significant direct effects indicated with solid line; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Overall, good model fit indicated by the hypothesized model: χ 2 (3, 224) = 6.53, p = .08; χ 2/df = 2.18; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; and RMSEA = .07

In reference to testing mediation, three indirect effects are present (presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4). According to the results of bootstrapping, father connectedness mediates the relationship between perceived academic interest and depression (B = −.34; SE = .10; p = .000; 95 % CI ranges from −.54 through −.16) in addition to the relationship between general perceived caring and depression (B = −.16; SE = .05; p = .004; 95 % CI ranges from −.29 through −.07). In reference to mother connectedness, this variable was found to mediate the relationship between perceived general caring and depression (B = −.33; SE = .08; p = .000; 95 % CI ranges from −.51 through −.17).

Father connectedness as a mediator between academic interest and depression. Unstandardized estimates reported with standard errors reported in parentheses; statistically significant direct effects indicated with solid line; statistically significant indirect effects indicated with dashed line; ***p < .001

Discussion

Using a national sample of Latina adolescents, we sought to determine the role of various familial factors on depressive symptomology. More specifically, we were interested in the role of mother and father connectedness as possible mechanisms that could account for the hypothesized caring-depression and academic interest-depression relationships.

As anticipated, results supported previous research on the relationship between perceived parental caring and academic interest (Ackard et al. 2006; Garcia et al. 2008). Also as anticipated and supported by the literature, perceived caring from parental figures was positively associated with feelings of connection with mother and father, respectively.

What is interesting to note is that perceived academic interest was positively related to feeling connected with father, but academic interest was not related to mother connectedness. This finding may be explained in the type of relationship and communication patterns fathers and mothers have with daughters. For instance, Youniss and Ketterlinus (1987) suggest that mother–daughter communication interactions are more open and at a deeper level than father–daughter interactions. Furthermore, mothers are more likely to talk about a variety of topics with daughters rather than limiting to just one (e.g., school life). Academic interest is only one aspect of an adolescent life and this interest was measured by asking whether or not parents talked with the participant about school. This does not represent a deep level of interaction that daughters may expect from mothers (Youniss and Ketterlinus 1987).

It is possible that for Latina participants, father–daughter communication expectations differ than for mothers. Punyanunt-Carter (2008) suggests that there are certain characteristics of the father–daughter communication that are associated with relationship satisfaction. Research has shown that daughters may be satisfied with the father–daughter relationship if fathers spend time with them, listen, and display sympathy (Buerkel-Rothfuss et al. 1995). Participants’ expectations on how parents engage with them may explain the significant association between academic interest-connectedness for fathers, while it was not significant for mothers.

Another anticipated finding is that the connection with mother and father is negatively associated with depression scores. This result supports previous research that an adolescent’s perceived closeness to a mother or father figure can influence the adolescent’s reporting of depressive symptoms (Resnick 2000). Although the relationship between perceived connectedness and depressive symptoms was established, results of the mediations analyses had mixed findings. In the parental caring-depression relationship, participant’s feelings of connection to both mother and father mediated the effects of depressive symptoms. That is, parental caring was associated with the Latina adolescent feeling a greater level of closeness and satisfaction with mothers and fathers. This level of closeness in turn was associated with less depressive symptoms. Our findings support previous research that suggests caring and a good relationship with parents are associated with positive mental health outcomes (Garcia et al. 2008).

In the association between parental academic interest and depressive symptoms, only father connectedness served as a mediator between the two variables. This suggests that the level of connectedness the Latina feels toward her father explains the academic interest-depression relationship. As previously noted, mother–daughter and father–daughter relationship expectations may differ (Punyanunt-Carter 2008). More research is needed to understand Latina adolescents’ expectations for mothers and fathers, respectively. Furthermore, research is needed to ascertain how fathers can intervene differently than mothers given these expectations from daughters.

Implications

Results from the study provide beneficial information for social workers and other mental health professionals working with Latina adolescents and families. It is clear that when a Latina adolescent perceives that her parents care, she is less likely to experience depressive symptoms. One way that parents can show that they care is by inquiring about the daughter’s school life. Having conversations around school life is an important way to create a sense of connectedness. This is particularly important for father–daughter relationships as noted in the findings of this study. When conducting interventions with parents, particularly fathers, social workers can encourage ways in which the parent can actively discuss topics that pertain to the daughter’s school life. Assisting parents in finding time to have these important conversations with daughters can have a positive impact on the relationship and depressive symptoms. Additionally, identifying a set time each week that is free from other distractions can help in facilitating a one-on-one communication.

Limitations and Future Research

Our research has some limitations that should be addressed. First, through looking at a single wave of the data, only cross-sectional analyses were possible. This limitation only allows this study to make predictive inferences and does not allow conclusions on causation to be made. Perhaps future studies could look at the process of caregiver-child caring, academic interest, and connectedness over the span of adolescent development in order to draw conclusions about the causal nature of these variables. In addition, future research would benefit from the use of more comprehensive and detailed measures of academic interest and involvement to determine the type of interest that is most valuable. Further, a more nuanced measure of connection with caregivers is needed. Given there are limited measures available, perhaps qualitative methods could be employed to investigate the Latina adolescent experience of being connected with her mother.

Summary and Conclusions

Despite the abovementioned limitations, the model derived from this study gives important information about the interplay of Latina adolescent family factors and depressive symptoms. With consideration of the role of parental caring, academic interest, as well as mother and father connectedness, mental health practitioners and stakeholders can make more informed decisions on areas to intervene when depressive symptomology is present. Given the differences in the relationship between father–daughter and mother–daughter connections, interventions should be customized to focus on the strengths of each type of relationship. The findings of the study suggest that a Latina’s perception of feeling connected and cared for by family does influence depression. The understanding of pathways by which perceived family connections and parental academic interests influences Latina adolescent depression can be used by clinicians to guide in developing culturally-informed interventions.

References

Ackard, D. M., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., & Perry, C. (2006). Parent–child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(1), 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013.

Buerkel-Rothfuss, N. L., Fink, D. S., & Buerkel, R. A. (1995). Communication in father–child dyad. In T. S. Socha & G. H. Stamp (Eds.), Parents, children, and communication: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 63–86). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Castillo, L. G., Perez, F. V., Castillo, R., & Ghosheh, M. R. (2010). Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 23, 163–175. doi:10.1080/09515071003776036.

Céspedes, Y. M., & Huey, S. J. (2008). Depression in Latino adolescents: A cultural discrepancy perspective. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 168–172. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.168.

Chance, S. E., Kaslow, N. J., Summerville, M. B., & Wood, K. (1998). Suicidal behavior in African American individuals: Current status and future directions. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4(1), 19. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.4.1.19.

Garcia, C., Skay, C., Sieving, R., Naughton, S., & Bearinger, L. H. (2008). Family and racial factors associated with suicide and emotional distress among Latino students. Journal of School Health, 78(9), 487–495. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00334.x.

Gulbas, L. E., Zayas, L. H., Nolle, A. P., Hausmann-Stabile, C., Kuhlberg, J. A., Baumann, A. A., & Peña, J. B. (2011). Family relationships and Latina teen suicide attempts: Reciprocity, asymmetry, and attachment. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(3), 317–323. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.4131.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kobus, K., & Reyes, O. (2000). A descriptive study of urban Mexican American adolescents’ perceived stress and coping. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 22(2), 163–178. doi:10.1177/0739986300222002.

Loehlin, J. C. (1998). Latent variables models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural analysis (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates.

Mombourquette, C. A. (2007). A study of the relationship between the type of parental involvement and high school student engagement, academic achievement, attendance, and attitude toward school. Dissertation Abstract International, 68(3). (UMI No. AAT 3258724) Retrieved August 11, 2011, from Dissertations and Theses database.

Piña-Watson, B., Castillo, L. G., Jung, E., Ojeda, L., & Castillo-Reyes, R. (2014). The Marianismo Beliefs Scale: Validation with Mexican American Adolescent Girls and Boys. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(2), 113–130.

Piña-Watson, B., Castillo, L. G., Ojeda, L., & Rodriguez, K. M. (2013). Parent conflict as a mediator between marianismo beliefs and depressive symptoms for Mexican American college women. Journal of American College Health, 61(8), 491–496.

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2008). Father–daughter relationships: Examining family communication patterns and interpersonal communication satisfaction. Communication Research Reports, 25, 23–33. doi:10.1080/08824090701831750.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306.

Rastogi, M., & Wampler, K. S. (1999). Adult daughters’ perceptions of the mother–daughter relationship: A cross-cultural comparison. Family Relations, 48, 327–336. doi:10.2307/585643.

Resnick, M. (2000). Protective factors, resiliency, and healthy youth development. Adolescent Medicine, 11, 157–164.

Rew, L., Thomas, N., Horner, S. D., Resnick, M. D., & Beuhring, T. (2001). Correlates of recent suicide attempts in a triethnic group of adolescents. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(4), 361–367. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00361.x.

Santiago-Rivera, A. L. (2003). Latinos, value, and family transitions: Practical considerations for counseling. Journal of Counseling and Human Development, 35, 1–12.

Turner, S. G., Kaplan, C. P., Zayas, L., & Ross, R. E. (2002). Suicide attempts by adolescent Latinas: An exploratory study of individual and family correlates. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 19(5), 357–374. doi:10.1023/A:1020270430436.

Weston, R., & Gore, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 719–751. doi:10.1177/0011000006286345.

Youniss, J., & Ketterlinus, R. D. (1987). Communication and connectedness in mother- and father-adolescent relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 263–280. doi:10.1007/BF02139094.

Zayas, L. H., Bright, C., Alvarez-Sanchez, T., & Cabassa, L. J. (2009). Acculturation, familism and mother–daughter relations among suicidal and non-suicidal adolescent Latinas. Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 351–369. doi:10.1007/s10935-009-0181-0.

Zayas, L. H., Kaplan, C., Turner, S., Romano, K., & Gonzalez-Ramos, G. (2000). Understanding suicide attempts by adolescent Hispanic females. Social Work, 45, 53–63. doi:10.1093/sw/45.1.53.

Zayas, L. H., Lester, R. L., Cabassa, L. J., & Fortuna, L. R. (2005). Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75, 275–287. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piña-Watson, B., Castillo, L.G. The Role of the Perceived Parent–Child Relationship on Latina Adolescent Depression. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 32, 309–315 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0374-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0374-0