Abstract

Humility is increasingly recognized as an essential attribute for individuals at top management levels to build successful organizations. However, research on CEO humility has focused on how humble chief executive officers (CEOs) shape collective perceptions through their interactions and behaviors with other organizational members while overlooking CEOs’ critical role in making strategic decisions. We address this unexplored aspect of CEO humility by proposing that humble CEOs influence decision-making decentralization at the top management team (TMT) and subsequently promote an organizational ethical culture. Using a sample of CEOs and TMT members from 120 small- and medium-sized enterprises, we find strong support for our hypotheses. We discuss important implications for research on CEO humility and strategic leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chief executive officers (CEOs) have received substantial scholarly and media attention due to their important role in making key strategic decisions and shaping organizational processes (Bromiley and Rau 2016a; Finkelstein et al. 2009). Research on CEOs and other top managers, commonly labeled as strategic leadership research, has suggested that a crucial challenge for CEOs in the current business environment is to use their authority to shape organizations that advance social good and behave ethically (Samimi et al. 2020). Accordingly, CEO humility emerged in management literature as a response to the need of studying leaders who recognize their limitations, find value in others’ strengths and contributions, accept others’ feedback, and by doing so, advocate for the interests of different stakeholders (Ou et al. 2018; Petrenko et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2017).

Humility is a stable characteristic that reflects the pursuit of an accurate self-view, acknowledgement that something greater than the self exists, appreciation of others’ contributions, and openness to the intervention of others (Ou et al. 2014; Owens et al. 2013). Humility has gained momentum in strategic management studies (e.g., Hu et al. 2018; Ou et al. 2018) in recent decades as society started to switch the view of an ideal CEO from an arrogant, narcissistic, self-sufficient individual to a more collaborative and cooperative leader (Zhang et al. 2017). This perspective change is partly explained by multiple organizational scandals in recent years, such as Facebook’s data harvesting for political campaigns in 2018 without users’ consent or Volkswagen’s violation of environmental protection guidelines, which have shown the importance of having CEOs who respect and pursue the interests of all stakeholders and shape their organizations to follow ethical principles.

Recent studies have indicated the relevance of CEO humility for various organizational outcomes such as performance (Petrenko et al. 2019), resilience and learning (Vera and Rodriguez-Lopez 2004), cooperation (Collins 2001; Frostenson 2016; Rego et al. 2019), and employee outcomes such as satisfaction and engagement (Owens et al. 2013). Studies on CEO humility claim that humble CEOs influence their firms by empowering employees (Ou et al. 2014), emphasizing self-transcendent pursuits (Morris et al. 2005), and promoting imitation of their behaviors (Owens and Hekman 2016). Overall, these studies have suggested that, by virtue of their position at the top of the organizational hierarchy, humble CEOs tend to convey extra meaning with their behaviors and interactions with other organizational members, thus shaping employees’ motivations, behaviors, and perceptions of what is expected from them.

Although highly informative, research on CEO humility has focused on how humble CEOs interact with other organizational members, but has not considered CEOs' role as strategic decision-makers and architects of organizational processes (Finkelstein et al. 2009; Miller and Dröge 1986; Parthasarthy and Sethi 1992). This oversight is surprising considering that a central focus of strategic leadership research is to understand how CEO characteristics shape strategic choices and subsequent firm-level outcomes (Bromiley and Rau 2016a; Busenbark et al. 2016; Miller and Toulouse 1986). Indeed, scholars have suggested the need for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which humility affects organizations (Nielsen and Marrone 2018). Thus, an important effort is to deepen our understanding of how humble CEOs might shape their organizations by influencing strategic decision-making processes.

Furthermore, organizations face increasing pressures to adopt environmental protection practices, contribute to social justice challenges, and encourage strong ethical behaviors from all organizational members (Wang et al. 2016). Still, research on how ethical culture can be shaped via strategic leadership and organizational processes is scarce (Chadegani and Jari 2016). Ethical culture is understood as the interplay of formal and informal behavioral control systems that promote or hinder ethical behavior (Sackman 1992; Treviño et al. 1998). Most research on ethical culture has focused on its outcomes (Kaptein 2011a; Ruiz-Palomino et al. 2013; Ruiz-Palomino and Martínez-Cañas 2014) and much less on its antecedents. Specifically, studies targeting the role of CEOs have explored ethical leadership (Eisenbeiss et al. 2015; Ofori 2009; Wu et al. 2015), CEO replacement after a crisis (Sims 2000), and CEO values (Berson et al. 2008). Although the CEO’s personal characteristics might influence ethical culture, we know little about the specific mechanisms that explain this relationship.

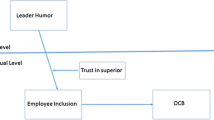

To explore this aspect of CEO humility, we advance a process model that explains how humble CEOs influence their firms’ ethical culture partially by shaping power decentralization for strategic decisions at the top management team (TMT). Considering that the TMT is composed of the CEO and the group of managers that report directly to the CEO (Hambrick and Snow 1977), decentralization at the TMT refers to the extent to which strategic decision-making is spread among TMT members and not concentrated solely on the CEO (Cao et al. 2010). We rely on upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason 1984) and consider humble CEOs’ tendency to appreciate the abilities and contributions of others (Ou et al. 2014) to argue that humble CEOs are motivated to share strategic decision-making authority with knowledgeable individuals who influence the firm’s strategic orientation, thus giving more decision-making discretion to their TMT members. Although decentralization can be a double-edged sword (Finkelstein 1992) as it might increase the likelihood of conflict at the TMT, we draw from the proposition of social learning theory that individuals learn from observing and imitating models (Bandura 1969) to argue that TMT decentralization for strategic decision-making processes encourages top managers to share more information and make more comprehensive decisions that take into consideration the interests of all stakeholders (Grojean et al. 2004), thus prioritizing the importance of the majority and promoting an ethical culture in the organization (Cullen et al. 1993; Kaptein 2011a; Trevino 1986). We present an overview of our model in Fig. 1, which indicates the partial mediation of TMT decentralization and the direct effect of CEO humility on ethical culture.

We test our predictions in a sample of 120 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operating in multiple industries and located across several regions in Colombia. SMEs have been used as an appropriate setting for strategic leadership studies because executives in these firms have more discretion due to reduced hierarchical levels and the occupation of both strategic and operational roles (Lubatkin et al. 2006). Furthermore, research indicates higher levels of power distance in Colombia versus other countries (Botero and Van Dyne 2009) and prevalence of centralized decision-making (Nicholls-Nixon et al. 2011), providing a valuable setting to explore the influence of humble CEOs on their firms.

Our paper contributes to strategic leadership and ethical culture research in multiple ways. First, we contribute to research on CEO humility by arguing that humble CEOs influence their organizations by shaping strategic decision-making processes. Existing research focuses on how humble CEOs form shared perceptions of norms and expected behaviors through their interactions with other organizational members (Ou et al. 2018; Rego et al. 2019), but we know little about how humble CEOs influence their firms through their decisions. We take an initial step in this direction by suggesting that humble CEOs acknowledge their limitations and share their authority with other TMT members to ensure that strategic decisions are more comprehensive. Second, we contribute to upper echelons theory by showing that some CEOs who actively seek to distribute power at the TMT can promote comprehensive decisions and influence firm-level outcomes such as ethical culture. Strategic leadership research assumes that CEOs’ power is an important predictor of the “CEO effect” (Finkelstein et al. 2009). Yet, we argue that humble CEOs can also imprint the organization with their characteristics, particularly by decentralizing decision-making and authority at the TMT. Third, we contribute to research on ethical culture by exploring new antecedents related to decision processes and CEO characteristics. Current research has shown that CEOs who set an ethical example can promote an ethical culture by becoming role models that other organizational members follow (Eisenbeiss et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2015). We show that CEOs can also promote an ethical culture by setting processes that favor inclusive and comprehensive strategic decisions and highlight the critical role of TMT decentralization for ethical culture. Finally, we address recent calls from strategic leadership scholars to not only develop process theories that explain the influence of CEOs through TMT processes (Liu et al. 2018), but also continue exploring various firm-level outcomes (i.e., ethical culture) that embrace the multifaceted nature of strategic leaders’ position (Samimi et al. 2020).

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Humility

Although humility has been contemplated across numerous cultures and religions (Morris et al. 2005), the organizational literature has conceptualized humility as a relatively stable trait with key cognitive components and behavioral manifestations. First, humility’s cognitive core is grounded in a self-view of accepting that something is greater than the self (Ou et al. 2014), which implies the experience of reflexive consciousness to seek accurate self-knowledge of strengths and limitations and pursue improvement (Nielsen and Marrone 2018). Accordingly, humility tends to manifest in interpersonal interactions by acknowledging of mistakes and feedback-seeking, a displayed appreciation of others’ strengths and contributions, and openness to learning from ideas and advice from others (Owens et al. 2013). Furthermore, humble individuals are engaged in self-transcendent pursuits, which motivates them to establish and seek goals that are less about themselves and more about moral principles and the greater good (Ou et al. 2014).

Humility is perceived to have similarities with other characteristics, such as modesty and narcissism. However, these constructs have important conceptual differences. First, humility is different from modesty because the latter reflects avoidance of attention on oneself (Peterson and Seligman 2004) and tends to understate an individual’s positive traits and strengths (Cialdini and de Nicholas 1989), whereas humility encompasses self-awareness and a balanced perspective of personal strengths and limitations without seeking to understate oneself (Morris et al. 2005). Second, narcissism could be understood as the opposite of humility because it encompasses a desire for attention and self-affirmation (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007). However, narcissism reflects an inflated sense of oneself and a need of external reinforcement (Gerstner et al. 2013), while humility reflects an accurate self-knowledge that involves accepting one’s strengths and weaknesses (Owens et al. 2013). Furthermore, humility has components not considered in narcissism, such as appreciation of feedback or self-transcendent pursuits (Ou et al. 2014). Accordingly, research has found that narcissism and humility can coexist at different levels (Zhang et al. 2017).

Similarly, humble individuals in leadership positions may depict behaviors reflecting authentic or servant leadership styles (Nielsen and Marrone 2018). However, there are important conceptual differences among these constructs. First, although authentic leadership emphasizes integrity and a sense of self-awareness of strengths and morals (Avolio et al. 2004), this view does not suggest an accurate representation of the self, an appreciation of others, and a desire to improve and grow (Nielsen and Marrone 2018). Second, servant leaders have a natural desire to serve others, prioritize their followers’ needs, and care about followers with greater need for help (Greenleaf 1970; Peterson et al. 2012). Although some servant leaders’ characteristics coincide with limited aspects of humility, the cognitive foundations and motivations of humility are different from the behaviors displayed by servant leaders (Ou et al. 2014). Serving others is not necessarily a motivation for humble individuals. Servant leaders’ main priorities are showing sensitivity to subordinates’ concerns, putting subordinates first, and helping subordinates grow (Peterson et al. 2012). Conversely, humility’s motivation emanates from self-transcendent pursuits and moral principles rather than servility with others (Nielsen et al. 2010). Overall, leaders’ traits and leadership behaviors are not isomorphic, and possible overlaps would focus only on limited aspects of humility (DeRue et al. 2011; Ou et al. 2014).

CEO Humility

Research on CEO humility is scarce but continues to gain attention in the literature due to its relevance for crucial outcomes. For example, CEO humility has been linked to large public organizations’ stock market performance (Petrenko et al. 2019). Ou et al. (2018) also found a relationship between CEO humility and organizational performance, mediated by the adoption of an ambidextrous strategic orientation in the TMT. Zhang et al. (2017) found that CEO humility interacts with the contradictory trait of CEO narcissism to increase innovation in the firm. Finally, CEO humility has been related to empowering leadership behaviors that promote integration in the TMT, which subsequently influence middle managers’ perceptions of empowerment that increases their work engagement, affective commitment, and job performance (Ou et al. 2014).

These studies generally suggest that humble CEOs influence their organizations through social interactions. Humble CEOs interact with the TMT members by empowering them (Ou et al. 2014), thus promoting an organizational climate of collaboration, information sharing, and shared vision (Ou et al. 2018). Humble CEOs also interact with other organizational levels as to shape an innovative culture by recognizing in other’s ideas the potential to contribute to the organization and by empowering the individuals capable of transforming relevant innovation processes (Zhang et al. 2017). Taking a different approach, Petrenko et al. (2019) propose that market analysts may form a perception of weak competitiveness for publicly traded firms led by humble CEOs, leading analysts to set low market expectations for humble CEOs that subsequently overperform those expectations even if the company performs averagely.

Overall, research on humble CEOs predominantly explores their role in shaping social interactions in the organization (e.g., Ou et al. 2018) and has begun to explore other aspects such as how they are perceived by external stakeholders (Petrenko et al. 2019). However, we have not explored how humble CEOs perform one of their key functions: shaping strategic decision-making processes (Samimi et al. 2020). Furthermore, despite the suggestion that organizational ethical behavior might be related to leadership humility (Argandona 2015; Nielsen and Marrone 2018), little is known on how humble CEOs might influence ethical culture through strategic decision-making processes. We suggest that TMT decentralization plays a key role in this process.

Decentralization

Studied extensively in both management and economics, the concept of decentralization is broadly understood as the transfer of power and authority from one or a few entities to more entities (Joseph and Gaba 2020). As such, decentralization can be both a characteristic of the organizational hierarchy (i.e., how a firm organizes multiple divisions and delegates authority to its members) (Boone et al. 2019) or a characteristic of a team (i.e., how team leaders share decision-making authority with their team members) (Zhu et al. 2018). Because we focus on how humble CEOs share strategic decision-making authority with the members of the TMT, we conceptualize decentralization at the TMT level as the “extent to which responsibilities for strategic decisions are shared within the TMT rather than being dominated by the CEO” (Cao et al. 2010, p. 1278). Decentralization at the TMT is relevant because it determines the extent to which TMT members have input and share their perspectives on the firm’s most significant decisions (Finkelstein 1992).

A CEO’s decision to share decision-making with TMT members can have mixed outcomes (Finkelstein and D’Aveni 1994). On the one hand, Boone and Hendriks (2009) show that decentralization of decision-making in the TMT increases the benefits of diversity by enhancing unique information sharing. By empowering knowledgeable individuals in the TMT, the CEO allows optimal resource allocation (Bunderson 2003; Greve and Mitsuhashi 2007), facilitating political behavior and coalition formation among TMT members (Eisenhardt and Bourgeois III 1988). A more cohesive and colluded team has a positive impact on organizational outcomes by creating more flexible systems and information exchange, allowing members of the company to adapt to dynamic environments and turnaround performance by increasing information flow and depth and breadth of analysis to formulate strategies (Abebe et al. 2011; Pitcher and Smith 2001). Thus, TMT decentralization can increase firm performance through multi-perspective decision-making (Pitcher and Smith 2001; Smith et al. 2006; Tang et al. 2011). Research also suggests that TMT decentralization helps firms facilitate ambidexterity and innovation opportunities by enhancing TMT members’ leeway and motivation to apply their knowledge and expertise (Heavey and Simsek 2017; Cao et al. 2010). Spread of strategic decision-making has been shown to lessen the opportunities for top managers to abuse power and decreases the likelihood of wrongdoing (Schnatterly et al. 2018).

On the other hand, TMT decentralization and its associated consideration of multiple perspectives on the strategic orientation of the firm can lead to conflict among TMT members (Abebe et al. 2011). Conflict is not inherently negative, but it can be detrimental when causing relationship tension, diverting the attention of top managers from relevant goals (De Dreu and Beersma 2005; Liu et al. 2009). Conflict literature (Jehn 1997) distinguishes between task (i.e., disagreement in points of view) and relationship conflict (i.e., personalized emotional incompatibility towards an individual). Research suggests that healthy amounts of task conflict help to make better decisions in the TMT, but relationship conflict can be detrimental for the company because it can produce antagonism and tension among members, deviating attention from tasks (Amason 1996; Jehn 1997; Jehn et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2009). Accordingly, a centralized TMT (i.e., a powerful CEO) can facilitate unambiguous leadership, goal setting alignment, and unity of command, which can diminish likelihood of any type of conflict (Mueller and Barker III 1997; Ocasio 1994), but diminishes TMT members’ ability to share information and promote diverse perspectives.

In synthesis, research consistently suggests that while TMT power decentralization facilitates information sharing and serves as a mechanism to incorporate diverse perspectives with positive organizational implications (Finkelstein 1992), it can generate conflict among TMT members (Liu et al. 2009). However, the presence of conflict does not necessarily imply that TMT members will stop sharing information or make collective decisions because conflict can increase depth of discussion and result in comprehensive decisions (Cao et al. 2010). Moreover, a centralized TMT does not guarantee a lack of relationship conflict (Amason 1996). It can compromise the benefits of having task conflict and even diminish perceptions of fairness (Korsgaard et al. 1995). These ideas suggest that TMT power decentralization is important to incorporate diverse perspectives in strategic decisions as long as TMT members are willing to share their input. We build on these insights in the hypotheses development to explore how TMT decentralization mediates the positive effect of CEO humility in organizational ethical culture.

Ethical Culture

We follow Trevino et al.’s (1998) conceptualization of ethical culture as “a subset of organizational culture, representing a multidimensional interplay among various formal and informal systems of behavioral control that are capable of promoting either ethical or unethical behavior” (p. 451). The formal systems of ethical culture are related to leadership, authority, structure, and policies, while the informal systems focus on behaviors and perceived norms (Ardichvili et al. 2009). To explore the consequences of its multiple outcomes, research has built on how ethical culture shapes individuals’ ethical reasoning and ethical behaviors. For example, ethical culture has been related to reduced falsifying, stealing, wasting (Kaptein 2011a; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010) and corruption (Webb 2012) because clarity of ethical standards and role modeling facilitate alignment of member’s behavior with organizational ethical norms. Ethical culture has also been related to whistle-blowing intentions or justice and fairness because companies are expected to follow procedural and retributive justice (Ardichvili et al. 2009; Trevino and Weaver 2001; Zhang et al. 2009). Furthermore, ethical culture has been found to influence ethical reasoning variables such as judgement (Sweeney et al. 2010), idealism (Tsai and Shih 2005), and moral imagination (Moberg and Caldwell 2007) because norms and role modeling are associated with learning and cognitive processes. Overall, research suggests that the organization’s ethical culture is positively associated with organizational members’ ethical intentions, reasoning, and actions.

It is important to clarify how our conceptualization of ethical culture relates to both organizational culture and national culture. First, ethical culture is a subset of organizational culture, as stated by Trevino et al. (1998). According to Schein (2010), organizational culture refers to “shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaption and internal integration, which has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems” (p. 18). Being a subset of organizational culture, ethical culture shares two important dimensions. First, values and beliefs (formal and informal) are central to the formation of basic assumptions, and both are learned through a social learning process. Second, leaders of the organization shape values and beliefs that imprint the culture. Thus, ethical culture shall be understood as embedded in organizational culture and subject to a similar formation process.

Second, culture can show cross-fertilization among levels of analysis (Schein 2010). Some studies found differences among national cultures in how individuals perceive ethics (Su et al. 2007), suggesting that national culture could influence organizational ethical culture. However, there is limited evidence on the relationship between national culture and organizational ethical culture (Mayer 2014). Additionally, studies have found that organizational culture exerts a more significant influence in ethical decision-making than national culture because it is a more proximal reality to employees’ daily decisions, which are aligned with organizational values rewarded by the firm (Westerman et al. 2007). This is consistent with research that has found relevant differences in organizational ethical culture of different firms operating in similar environments (Schneider and Barbera 2014). Thus, although national culture can infuse organizations with specific values and behaviors (Ardichvili et al. 2012), organizations seem to play a more critical role in shaping ethical decision-making within their boundaries.

Although research on the antecedents of ethical culture is scarce (Mayer 2014), the fact that formal and informal systems compose ethical culture suggests that top managers should have an important influence over it. Specifically, top managers not only put in place formal policies, authority, and structure to guide the strategic orientation of the firm but also influence employees through their symbolic role and example of accepted behaviors, making ethical culture particularly subject to their influence (Finkelstein et al. 2009; Schaubroeck et al. 2012). Thus, exploring strategic leadership antecedents of ethical culture can be an essential effort to understand determinants of ethical behavior and its associated organizational implications.

Hypotheses

CEO Humility and TMT Power Decentralization

Upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason 1984) proposes that strategic leaders act based on their interpretation of the firm’s strategic situations, and this interpretation is influenced by their characteristics. Managers are prompted by perceptions to act, influencing strategic choices and subsequent firm-level outcomes. Furthermore, scholars argue that CEOs influence not only organizations but also all TMT members through their characteristics, interactions, and involvement with strategic decision-making (Michel and Hambrick 1992; Liu et al. 2018; Wiersema and Bantel 1992). Decentralization at the TMT is relevant for the formulation and implementation of strategies because it characterizes how members of the TMT are involved in strategic decisions and reflects the CEO’s degree of dominance in making those decisions. Specifically, in a decentralized TMT, strategic decision-making processes involve the participation of all TMT members rather than being concentrated on the CEO (Finkelstein 1992; Finkelstein and Hambrick 1996). We argue that humble CEOs will influence TMT decentralization in two main ways.

First, we expect that humble CEOs collaborate with the TMT, are more transparent, share information, and understand the organization’s functioning as a collective effort (Aime et al. 2014; Anderson and West 1998). This willingness to be open to the others’ participation in organizational decision-making is partially explained by humble CEOs’ accurate self-awareness of strengths and weaknesses, which motivates them to look for collaboration to overcome their limitations (Argandona 2015; Hu et al. 2018). Humble CEOs are active in searching for others' perspectives, experiences, capabilities, and contributions, as they acknowledge their own limits and recognize the need for other individuals to be involved to make the organization better (Owens et al. 2013). Thus, humble CEOs are interdependent to their collaborators, as they seek the idiosyncratic contributions of others in making the organization unique, competitive, and sustainable (Frostenson 2016; Ou et al. 2014).

Second, humble CEOs want to receive feedback on their job and learn from others (Hu et al. 2018; Collins 2001). TMT members feel confident in sharing their opinions and perspectives with their humble CEOs, as they perceive that their contribution will be seriously considered and appreciated (Argandona 2015). Humble CEOs would establish processes that allow feedback channels and active communication with the TMT, as they appreciate different perspectives and seek to learn from top managers, thus allowing TMT members to contribute with their knowledge to the firm’s strategic orientation. Finally, humble CEOs believe that something greater than themselves exists (Ou et al. 2014). Thus, humble CEOs are likely to avoid autocratic processes that only follow their own commands and interests, and rather share strategic decision-making responsibility to fulfill their conviction that the common good is more important than the self-benefit.

Overall, humble CEOs are motivated to shape decision processes focused on promoting the interests of all and appreciating others’ contribution, which implies that the input of multiple TMT members is considered in strategic decision-making processes and power is spread among the members of the TMT (Owens and Hekman 2012). We, therefore, suggest that humble CEOs are more likely to consider the participation and contributions of all TMT members and decentralize the strategic decision-making process.

Hypothesis 1

CEO humility is positively associated with TMT power decentralization.

TMT Decentralization and Ethical Culture

We suggest that TMT decentralization will promote the organization’s ethical culture in multiple ways. First, a decentralized TMT allows top managers to share information and incorporate different perspectives in their strategic decision-making processes (Cao et al. 2010). Executives in decentralized TMTs are willing to create productive communication channels to collectively work for a common goal, consider the perspectives of all TMT members, and contemplate the viewpoints of different functional areas of the organization (Cao et al. 2010; Haleblian and Finkelstein 1993). The inclusion of different perspectives is an essential precursor of an ethical culture (Mayer 2014; Schein 2010; Stewart et al. 2011). Specifically, an ethical culture represents a shared belief among the organization members that the collective well-being is prioritized over self-interested behaviors (Key 1999; Kohlberg and Hersh 1977). Ethical culture is associated with perceptions of fairness and justice in the organization (Ardichvili et al. 2009; Weaver and Trevino 2001), creation of an open-ended collaborative system (Aselage and Eisenberger 2003), and a context where different levels participate to agree on acceptable behaviors and values (Barnett and Schubert 2002). Accordingly, considering multiple perspectives and emphasizing more collective and comprehensive decision-making processes is key to establish an ethical culture (Argandona 2015; Kaptein 2011b; Trevino 1986; Wu et al. 2015). Thus, decentralized TMTs will promote ethical culture because these TMTs debate decisions, consider multiple perspectives, discuss various alternatives, and evaluate possible consequences (Pitcher and Smith 2001). Furthermore, a more comprehensive decision-making approach allows the organization to be more inclusive of the interests of all constituencies and to reduce the probability of harming a stakeholder in any decision, promoting the belief among organizational members that the firm makes ethical decisions (Cullen et al. 1993).

Second, besides promoting ethical culture through comprehensive and inclusive strategic decisions, we also argue that TMT decentralization can shape how other organizational members at different hierarchical levels promote ethical behaviors. Social learning theory (Bandura and Walters 1977) argues that individuals learn and acquire new behaviors by a cognitive process of observation and imitation of the actions of individuals that surround them (Grusec 1994). When strategic leaders include all relevant perspectives in their decisions, the rest of the organization’s employees will tend to learn this behavior because oral and visual information from models facilitate retention (learning) and reproduction of behaviors (Bandura and Walters 1977). Following this logic, we argue that shared decision-making processes in the TMT are likely to signal the importance of collaborative behaviors throughout the firm, promote information sharing in subsequent levels of the organization, and increase the openness of organizational members to share diverse perspectives. In turn, this will favor a generalized tendency in the organization to consider various constituencies’ interests, promoting an ethical culture (Grojean et al. 2004).

Research suggests that TMT decentralization may lead to conflict, which is particularly harmful when it causes tensions and animosity among TMT members because it can lower satisfaction or commitment (De Dreu and Beersma 2005; Liu et al. 2009; Simons and Peterson 2000). Following our arguments, TMT decentralization could hamper ethical culture if such conflict inhibits TMT members’ ability to engage in collaborative decision-making. This is unlikely for three main reasons. First, decentralized TMTs would still have to comply with the established decision-making procedures of their firms, thus leading TMT members to contribute with their input and share diverse perspectives even if some members are engaged in relational conflicts. Second, the uncertainty of strategic decisions and the high-stakes environment of TMTs are likely to force members to limit relationship conflicts and favor the benefits of discussing strategic issues in a comprehensive manner and consider their opposing views (Cao et al. 2010). Finally, research suggests that a shared understanding of authority can increase psychological empowerment (Gomez and Rosen 2001). Such empowerment strengthens relationships among TMT members and thus diminishes the risks of relationship conflict while taking advantage of the benefits of task conflict (Carmeli et al. 2011; Dulebohn et al. 2012). Thus, we expect TMT decentralization to promote an ethical culture by emphasizing collective and comprehensive decision-making processes and by promoting learning of these behaviors in subsequent organizational levels.

Hypothesis 2

TMT decentralization is positively associated with organizational ethical culture.

Mediating Role of TMT Decentralization

We propose that CEO humility influences organizational ethical culture through TMT decentralization. However, CEOs engage in multiple behaviors that can influence similar firm-level outcomes through different mechanisms (Samimi et al. 2020). Top managers shape organizational culture in different ways (Schaubroeck et al. 2012; Schein 2004). Therefore, we acknowledge that the influence of humble CEOs on ethical culture may not only be explained by TMT decentralization but also by other possible mechanisms.

Specifically, research shows a generalized consensus that leadership plays an important role in ethical culture (Ardichvili et al. 2009; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). As ethical culture is a combination of formal and informal systems (Trevino et al. 1998), our arguments of how humble CEOs influence ethical culture through TMT decentralization emphasize the formal systems that support ethical culture (i.e., TMT decentralization). However, research on CEO humility also suggests that humble CEOs shape informal culture systems, such as shared perceptions of values accepted in the organization (Morris et al. 2005; Ou et al. 2018). Humble CEOs may reinforce values of ethical behavior by communicating their focus on moral principles, praising individuals who encourage self-transcendent goals, and overall serving as models for other organizational members to follow (Giberson et al. 2009). Thus, humble CEOs might influence ethical culture by shaping formal decision-making processes to favor inclusiveness and shaping other informal systems of culture and serving as role models for other organizational members to follow (Wood and Bandura 1989).

Humble CEOs might shape ethical culture informally by developing a sense of reciprocity with other organizational members, which motivates other areas of the company to be more inclusive in their decisions. More specifically, humble CEOs’ focus on leveraging TMT members’ strengths and trusting them to make decisions is likely to strengthen relationships between TMT members and the CEO (Ilies et al. 2007). A strong relationship is likely to encourage subordinates to reciprocate in a way consistent with their leader’s values (Bauer and Erdogan 2015; Gerstner and Day 1997). TMT members are likely to develop this sense of reciprocity when they perceive more support from the CEO (Kottke and Sharafinski 1988), that they are trusted with their role (Schoorman et al. 2007), and that the CEO is empathetic of their reality (Colbert et al. 2008), which are likely to occur with a humble CEO who appreciates others’ contributions and their ideas. In turn, it is likely that TMT members reciprocate by sharing decision-making authority with knowledgeable subordinates, making more comprehensive and inclusive decisions, and shaping interactions at other organizational levels to promote ethical behavior.

Humble CEOs might also shape ethical culture through informal systems by setting an example for other organizational members to follow. Specifically, CEOs who appreciate others’ contributions and recognize their limitations are likely to stand out in the organizational context (Brown et al. 2005). Organizational members are thus likely to notice that their humble CEOs promote goals and objectives infused with collective and self-transcendent features rather than personal benefits, which can motivate organizational members to put the interests of the organization and society ahead of their own, consider the long-term impact of their decisions, and embrace their responsibilities with other stakeholders, therefore promoting an ethical culture (Wu et al. 2015).

Overall, we suggest that TMT decentralization partially explains the influence of humble CEOs on their organization’s ethical culture because humble CEOs can also influence additional informal systems that shape ethical culture.

Hypothesis 3

TMT decentralization partially mediates the relationship between CEO humility and organizational ethical culture.

Methods

Sample

We gathered data from SMEs operating across different industries in Colombia. Aguinis et al. (2020) recently proposed Latin America as an outstanding, unexplored region to do leadership research considering its apparent high respect for power and authority. Consistently, research has shown relatively higher levels of power distance in Colombia compared to other countries (Botero and Van Dyne 2009), highlighting the authority of Colombian CEOs on determining key strategic decisions of the firm and providing a valuable setting for showing the potential effects of CEO humility on firm behavior and culture. Additionally, CEOs of SMEs can have high levels of managerial discretion due to few hierarchical levels, occupation of both strategic and operational roles, and usual controlling ownership (Farrell and Winters 2008; Lubatkin et al. 2006). This can increase the likelihood that strategic leaders’ characteristics and decisions influence organizational culture. Finally, Latin America is highly dependent on family and small businesses (Aguinis et al. 2020), allowing the findings of our study to have important implications for a large context.

We followed a back-translation strategy and prioritized semantic equivalence to develop the questionnaire and capture our measures. The initial questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Spanish by a researcher fluent in both languages. Two Colombian researchers, initially unaware of the study’s purpose, assisted with the back translation into English. All discrepancies were thoroughly discussed to ensure semantic equivalence, i.e., that cultural and language considerations were carefully considered to make sure that the same meaning was conveyed by the translated items (Schaffer and Riordan 2003). The final questionnaire was pilot tested with 10 Colombian managers, who provided feedback and guidance for additional minor changes.

With the assistance of a marketing agency, we searched for directory-type information of over 5000 Colombian SMEsFootnote 1 using Chambers of Commerce as well as the government’s department of statistics. The marketing agency assisted us with collecting this information, scheduling appointments, and personally visiting top managers to obtain survey responses. Considering that studies surveying top managers typically have low response rates, particularly when the survey has more than one phase (approximately 10%), we randomly selected 1443 SMEs to target a final usable sample of 140 firms, a typical sample size in strategic leadership studies collecting primary survey data (see Bromiley and Rau 2016a, b). These SMEs were located in multiple cities and operated in multiple industries. We contacted these CEOs by telephone and asked them to participate in a two-stage survey about their organizations. Initially, 403 CEOs agreed to participate and were visited to deliver and answer the survey personally. We dropped 22 firms from this first phase when the CEO was not available at the time of the appointment or when another manager unexpectedly replaced the CEO to answer the survey, leaving 381 SMEs in the first stage. At the end of the survey, we asked CEOs to provide contact information of another key member of the TMT to gather additional data. We surveyed the TMT member six months after surveying the CEO. Using two respondents per firm allowed us to reduce common method bias concerns. After the two rounds of the survey concluded and we checked missing data, we had a final sample of 120 firms in which both the CEO and a TMT member answered the survey. Our final 8% response rate is similar to that of strategic leadership studies conducted in SME settings (Alexiev et al. 2010; Koryak et al. 2018; Kraiczy et al. 2015). The final sample of SMEs had, on average, approximately 23 years of age and 132 employees. Many of these SMEs operated in the retail industry (37%), followed by manufacturing (23%), services (20%), food (8%), healthcare (7%), and electrical (6%). The CEOs had, on average, approximately 41 years of age and had been on their position for approximately 7 years. Half of these CEOs were female, 20% had founded their firms, and approximately 68% had undergraduate or graduate degrees.

To check for possible non-response bias, we conducted a one-way ANOVA comparing key firm characteristics (age and size) of firms in the first phase of the survey that did not participate in the second phase. We found no significant differences between these two groups of SMEs in terms of firm age and firm size. We also conducted a one-way ANOVA to compare CEOs of SMEs in the first phase and those of the second phase. We found no significant differences in terms of CEO tenure, gender, or level of education.

Besides obtaining data from two executives for each firm, we followed additional recommendations to alleviate common method bias concerns by ensuring anonymity (there was no identifying information in the survey) and reducing evaluation apprehension by communicating to the respondents that there were no right or wrong answers (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Furthermore, several of our constructs are free of methodological bias because they are objective measures rather than subjective assessments (e.g., CEO age, CEO tenure, firm size, firm age). Once data had been collected, we also performed the Harman one-factor test (Harman 1967), including all items of the main constructs in an exploratory factor analysis to assess the number of factors that explain most of the variance. The test indicates the presence of common method bias if one factor explains more than 50% of the variance or if a single factor emerges from the analysis. The test indicated that the three main factors are needed to explain the majority of the variance. Thus, the test provides additional evidence that common method bias is not a critical concern.

Our analysis is based on a survey in which CEOs are the key informants for organizational outcomes (i.e., ethical culture). This approach is consistent with studies conducted in samples of SMEs (Dehlen et al. 2014; Kammerlander et al. 2015), where CEOs represent a relevant respondent group who is well positioned to provide general evaluations of the firm (Patel et al. 2013) and can have accurate insights for firm characteristics such as ethical culture (Wu et al. 2015), organizational culture (e.g., Laforet 2016), stakeholder culture (e.g., Jiao et al. 2017), and innovative culture (e.g., Wolf et al. 2012). Furthermore, in cases where obtaining additional data is challenging, as was our case due to the cost-intensive effort of surveying top managers of SMEs, research suggests that CEOs’ self-reported measures are reliable (Dess and Robinson 1984; Torugsa et al. 2012).

Measures

We measured CEO humility using an 11-item scale developed and validated by Owens et al. (2013) and extended by Owens et al. (2015) for leadership settings. This scale captured CEOs’ willingness to view themselves accurately, appreciate others’ contributions and strengths, be open to ideas and feedback, admit their mistakes, and be aware of their strengths and weaknesses. TMT members rated their CEOs on a 5-point agreement scale. The reliability of this scale was above accepted levels (α = .94).

We measured TMT decentralization by asking TMT members about the decision-making process in nine strategic areas (Cao et al. 2010). More specifically, TMT members were asked to “indicate whether decisions on the following criteria are made by the CEO alone, by the CEO with one or few TMT members, by the CEO with most or all TMT members, or by the entire TMT as a group”. Criteria presented for these decisions was new product introduction, new market expansion, strategic alliance formation, budgeting, financing, key people hiring, production/manufacturing, marketing/sales/service, and strategic direction planning. We aggregated ratings across these strategic decision areas. Thus, higher values indicate a higher degree of decentralization. Reliability for this scale was above accepted levels (α = .92).

We measured organizational ethical culture using the 9-item scale adapted by Wu et al. (2015) from the scale developed by Key (1999). This scale relies on top managers to provide information about the organization’s ethical conduct. Specifically, CEOs rated on a 5-point scale the extent to which they agreed with various statements about the organization’s ethical standards and behavior. Sample items include: “Employees in our company accept organizational rules and procedures regarding ethical behavior, “Penalties for unethical behavior are strictly enforced in our company”, and “Ethical behavior is rewarded in our company”. Reliability for this scale was above accepted levels (α = .92).

We controlled for multiple CEO-, firm-, and industry-level variables. Numerous reviews on strategic leadership have shown that CEO age, gender, education, tenure, and founder status can have important implications for multiple firm-level outcomes (see Bromiley and Rau 2016a; Busenbark et al. 2016). Thus, we measure CEO age in years, CEO gender as a binary variable coded 1 for male and 2 for female, CEO education as a rank variable between 1 and 4 capturing level of education (1 for less than high school, 2 for high school, 3 for undergraduate degree, and 4 for graduate degree), CEO tenure as the number of years in the position, and founder status as a binary variable coded 1 for CEOs who founded their firms and 0 otherwise.

Firm size and firm age can affect the development of organizational ethical culture (Eisenbeiss et al. 2015; Schminke et al. 2005). Thus, we controlled for firm size using the number of employees in the organization and for firm age using the number of years since the founding of the firm. Finally, industry characteristics might induce ethical challenges and conflicting situations that strategic leaders need to handle. Thus, we included industry dummies in our analysis.

Analysis

In the analysis, we used TMT members’ responses on CEO humility and TMT decentralization, and we used CEOs’ responses for ethical culture and control variables. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess our hypothesized model’s fit with the data. We tested the fit of the measurement model before testing our hypothesized structural model and comparing it with alternative and plausible models (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). The SEM approach indicates partial mediation when the model shows acceptable goodness of fit and the following paths are significant: independent variable and mediating variable (CEO humility to TMT decentralization), mediating variable and dependent variable (TMT decentralization to ethical culture), and independent variable and dependent variable (CEO humility and ethical culture) (James et al. 2006). In other words, there is evidence of partial mediation when all paths displayed in Fig. 1 are significant, and the model shows acceptable goodness of fit (James et al. 2006). In contrast, the SEM approach indicates full mediation when the model without the path between the dependent and independent variable shows acceptable goodness of fit, and its paths from the dependent variable to the mediating variable and from the mediating variable to the dependent variable are significant. We compare our partial mediation model with this alternative full mediation model below (Fig. 2).

To estimate the fit of the measurement and structural models, we examined the extent to which the covariances estimated in the model matched the covariances in the measured variables using the chi-square (χ2). We also use additional indexes such as the comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A value of 0.90 or higher for CFI, IFI, and TLI and a value of 0.08 or lower for RMSEA are typically suggested as adequate fit indicators (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Results

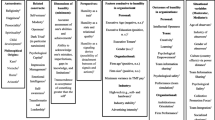

We provide descriptive statistics and correlations for our study variables in Table 1. The measurement model shows acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 972.26, df = 686, CFI = .89, TLI = .87, IFI = .90; RMSEA .05). We compared this three-factor model with alternative two- and one-factor models to verify the constructs’ distinctiveness before testing the hypotheses. First, we tested a two-factor model in which CEO humility and TMT decentralization form a single factor and ethical culture remains as a single factor. This model shows poor fit to the data (χ2 = 1489.13, df = 700, CFI = .70, TLI = .65, IFI = .71; RMSEA .10). Second, we tested a two-factor model in which TMT decentralization and ethical culture form a single factor and CEO humility remains a single factor. This model shows poor fit to the data (χ2 = 1419.38, df = 700, CFI = .73, TLI = .68, IFI = .74; RMSEA .9). Finally, we tested a one-factor model in which CEO humility, TMT decentralization, and ethical culture form a single factor. This model shows poor fit to the data (χ2 = 1989.03, df = 713, CFI = .51, TLI = .45, IFI = .54; RMSEA .12). These results in tandem provide clear evidence of the distinctiveness of the three main variables in the study and support the assessment of the hypothesized structural model.

The results for the hypothesized model suggest that our hypothesized partial mediation model fits the data well (χ2 = 972.26, df = 686, CFI = .89, TLI = .87, IFI = .90; RMSEA .05). As we show in Fig. 1, results indicate a positive and significant relationship between CEO humility and TMT decentralization (β = .44; p < .001), providing support for Hypothesis 1. Results also indicate a positive and significant relationship between TMT decentralization and ethical culture (β = .23; p < .05), providing support for Hypothesis 2. Finally, the direct path from CEO humility to ethical culture is positive and significant (β = .26; p < .05) and the indirect effect of CEO humility on ethical culture, calculated through a bootstrap approximation of bias-corrected confidence intervals, is positive and significant (β = .17; p < .001). This provides support for Hypothesis 3.

Following Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) suggestions, we tested plausible alternative models to test the mediation hypothesis further. We present these results in Table 2. First, we tested a fully mediated model by removing the direct path from CEO humility to ethical culture. Although coefficients are significant, this fully mediated model is not significantly better than our hypothesized model, and all the model fit indexes are below the ones with the partially mediated model. Similarly, the non-mediated model, which has no path from CEO humility to TMT decentralization, indicates an increase in chi-square, and all the model fit indexes are below the ones with the partially mediated model. These comparisons suggest that the partially mediated model has the best fit and provides further support for Hypothesis 3.

Although these results using SEM analysis provide strong support for our hypotheses, we also include results using ordinary least squares based on the incremental approach of Baron and Kenny (1986). This method involves estimating three regression equations: ethical culture regressed on CEO humility, TMT decentralization regressed on CEO humility, and ethical culture regressed on both CEO humility and TMT decentralization. This approach indicates partial mediation when the inclusion of the mediating variable (TMT decentralization) as predictor of the dependent variable (ethical culture) reduces the coefficient of the dependent variable (CEO humility), but the coefficient remains significant. Should this coefficient become non-significant, the results would support full mediation. We show the results of this analysis in Table 3.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, model 1 indicates that CEO humility is positively and significantly associated with TMT decentralization (β = .41; p < .001). Model 3 shows that TMT decentralization is positively and significantly associated with ethical culture (β = .48; p < .001), supporting Hypothesis 2. Finally, model 2 indicates that CEO humility is positively and significantly associated with ethical culture (β = .48; p < .001), while model 4 shows that this coefficient becomes smaller yet remains significant (β = .24; p < .05) once TMT decentralization is included in the model (β = .38; p < .001). This result provides support for our partial mediation prediction in Hypothesis 3.

Post Hoc Analyses

Although strategic leadership research regularly captures organizational-level variables by surveying CEOs (e.g., Cao et al. 2015; Gupta and Govindarajan 1986; Laforet 2016), we have emphasized that ethical culture represents a shared perception of the organization’s beliefs and values from employees at different levels of the organization. Thus, to increase confidence in our main results, we collected additional ethical culture data from a subsample of firms approximately one year after the main data collection concluded. Specifically, we surveyed two non-executive employees from 30 firms and included the 9-item ethical culture questionnaire to compare the level of agreement between the CEO and the two employees on the organization’s ethical culture. From the 60 employees who replied to the survey, 66% were female, all respondents were between 18 and 35 years old, and had worked for the firm approximately three years on average. First, we calculated the inter-rater agreement (rwg, uniform distribution) among the scores of the CEO and the two additional employees (James et al. 1993). The resulting average rwg was 0.93, far above recommended values of 0.70. We also calculated intraclass correlations (ICC). An indication of convergence within firms is a relatively high ICC value with statistically significant analysis of variance F-statistic (Kenny and La Voie 1985). The ICC (1.1) value was 0.74 with a significant F-statistic (3.91; p = .00) and the ICC (1.3) value was 0.74 with a significant F-statistic (3.80 p = .00). This indicates that both employees and the CEO of each firm in this subsample have a high level of agreement on the level of their organization’s ethical culture, thus providing some evidence that the measure of ethical culture in our main analysis is reliable.

We included additional control variables in our analysis to test the robustness of our findings. These analyses are available from the authors upon request. First, considering that we could only survey one TMT member per firm, it was possible that other TMT members with different characteristics would have varied perceptions of their CEO’s humility or the level of decentralization at the TMT. Furthermore, TMT members with diverse characteristics may engage in more relational conflicts and limit how decentralized TMTs share information (Cao et al. 2010). Thus, we included a measure of TMT heterogeneity by asking the TMT member to rate on a 5-point scale, ranging from ‘very different’ to ‘very similar’, the extent to which TMT members in the firm are similar in terms of age, gender, years of experience, education background, and education levels. Second, it was possible that although decentralized TMTs tend to make strategic decisions as a group, they did not share or communicate their suggestions and information to a great extent when evaluating strategic options. In turn, this would limit the implications of TMT decentralization for ethical culture. Thus, we included a measure of TMT participation by asking TMT members to indicate, on a 5-point scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”, the level of agreement with statements about TMT members’ willingness to share ideas and suggestions to the CEO about the direction of the organization (Liang et al. 2012). The inclusion of these variables as covariates in our analysis did not change our main results.

Discussion

Increasing pressure and activism from different stakeholders have made it apparent that CEOs need to promote strong ethical behaviors in their organizations to help address social problems and context challenges (Porter and Kramer 2019). As such, humility represents an important trait for individuals in positions of authority because it signals receptiveness and flexibility to pursue the interests of all the constituencies that interact with organizations. However, most of the research on CEO humility has been limited to the influence of the CEO on the firm when interacting with others, overlooking that humble CEOs would also play a key role in shaping strategic decisions and organizational structure and processes (Hambrick and Mason 1984; Miller and Droge 1986). Drawing from upper echelons theory, social learning theory, and decentralization and ethical culture literatures, we take an initial step to address this point by suggesting that humble CEOs are likely to shape their TMT to make strategic decisions that incorporate perspectives of all TMT members (i.e., decentralized TMTs) and, in doing so, promote an ethical culture in their organizations. Our findings support our predictions that CEO humility is positively associated with TMT decentralization, that TMT decentralization promotes an ethical culture, and that TMT decentralization partially mediates the relationship between CEO humility and ethical culture. We elaborate on research and practical implications of our study below.

Implications for Research

Previous research on CEO humility explained the influence of humble CEOs predominantly based on their social interactions with other organizational members (Ou et al. 2014, Ou et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2017). Overall, researchers argued that humble CEOs rely on interactions to form perceptions of expected norms and values that influence behavior and shape important outcomes such as team creativity or firm performance (Hu et al. 2018; Ou et al. 2018). Building on the critical role of CEOs as strategic decision-makers and architects of organizational processes (Miller and Toulouse 1986; Samimi et al. 2020), we attempt to bring a new perspective to CEO humility research by exploring how humble CEOs influence organizations through strategic decision-making processes. Specifically, we find that humble CEOs promote organizational ethical culture by supporting decentralization in their TMT, therefore highlighting that humility can manifest at top organizational levels in terms of how strategic decisions are made.

We encourage future research to extend this decision-making aspect of CEO humility and explore how humble CEOs gather and process information for their decision-making processes and the strategies they tend to devise or favor. For example, due to their focus on self-transcendent pursuits, humble CEOs may formulate and pursue ambitious strategies that underscore the organization’s role for societal well-being. Similarly, humble CEOs’ focus on an accurate self-view of strengths and limitations may imply that their devised strategies tend to effectively leverage available resources and result in relatively fast implementation processes. Importantly, our support for partial mediation suggests that humble CEOs influence ethical culture and possibly other organizational outcomes through multiple mechanisms, as has been suggested by strategic leadership scholars (Samimi et al. 2020). We, therefore, encourage future research to explore and combine these mechanisms in empirical studies to uncover the main pathways that explain the influence of CEO humility and their relative importance. In doing so, it would be interesting to compare the interactive influence of CEO humility and other constructs with some overlap (e.g., servant or authentic leadership). Such efforts are critical to distill the most influential CEO characteristics (Bromiley and Rau 2016a, b), shed light on the constructs that are more relevant for TMT decentralization and ethical culture, and suggest the type of leadership style that humble individuals tend to adopt.

Our work also has implications for upper echelons theory (Hambrick and Mason 1984) and strategic leadership research (Samimi et al. 2020). Specifically, studies on CEO characteristics have suggested that power and authority are important determinants of the extent to which CEOs influence their organizations because increased power allows CEOs’ characteristics to manifest in their strategic decisions (Wangrow et al. 2015). However, our study proposes that humility can motivate CEOs to reduce their power, and that this can have interesting implications for organizational outcomes such as ethical culture. Thus, our work highlights that CEOs can play an active role in shaping their own power and that certain characteristics can motivate them to change their decision-making power and impact relevant organizational outcomes. We, therefore, encourage researchers to not only take a closer look at how humble CEOs engage in other behaviors and decisions that shape their power and authority in different ways but also explore other CEO characteristics that motivate CEOs to make changes in power distribution and the implications of those actions for organizations.

Although scholars in management have tested the proposition that organizational culture is influenced by top managers (Schein 2004, 2010), we have little evidence that this proposition holds for ethical culture. Most studies exploring ethical culture have centered on evaluating its consequences to employees’ outcomes such as whistle-blowing behavior (Kaptein 2011a), ethical judgement (Sweeney et al. 2010), or moral imagination (Moberg and Caldwell 2007). Nevertheless, we know much less of CEO-level antecedents of ethical culture. Some evidence suggests an effect of CEOs on ethical culture (Berson 2008; Eisenbeiss et al. 2015; Sims 2000; Wu et al. 2015), but we know little about the mechanisms that explain this relationship and the diverse CEO characteristics that are important. By studying how humble CEOs shape ethical culture, we emphasize the critical influence of CEO characteristics on organizational culture and take an initial step on developing mechanisms that shed light on how CEOs shape their firms’ ethical behavior. We encourage future researchers to extend this work by using longitudinal studies, exploring boundary conditions that shape these relationships, and incorporating the role of middle managers in our model.

Implications for Practice

Society is increasingly demanding organizational leaders to embrace actions that address society’s most pressing challenges such as economic inequality or climate change (McWilliams et al. 2006). Our research can help CEOs in this effort by showing one pathway through which their organizations can be more comprehensive of stakeholders’ interests and avoid ethical lapses. Specifically, our research can help CEOs, particularly those leading SMEs, to contemplate multiple perspectives and more inclusive strategic decisions to allow stakeholders’ interests to be reflected in organizational actions that can ultimately encourage an ethical culture in the organization.

Our work is also relevant for CEO selection and training. First, some firms can receive strict scrutiny from their stakeholders, placing important demands for organizations to behave ethically. Our work can support boards of directors in their CEO selection and appointment decisions by showing that humility can be an important trait to consider when ethical behavior needs attention or enforcement. Second, our research suggests that there can be important benefits from coaching CEOs to be open to feedback, appreciate contributions from their TMT members, and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses. Although humility is a characteristic that remains relatively stable throughout a lifespan, individuals can learn some of these behaviors from exposure to models and training (Ou et al. 2014). Thus, firms can set training programs for CEOs and potentially set succession plans that train future leaders of the organization in these behaviors.

Limitations

As in every research, our work is not free of limitations. First, the confidence that we have about the accuracy of the measurement of humility can be harmed because only one TMT member per firm rated their CEO’s humility. Although the measurement of individuals’ personal characteristics can be more accurate when it is others-rated (DeYoung et al. 2007), it would be beneficial in future research to have at least one more rater of CEO humility to increase the reliability of the measurement. Relatedly, our measure of ethical culture was captured via the CEO only, but other employees represent an eligible source to assess ethical culture. Although our post hoc analysis partially alleviated this concern by showing agreement between CEOs and two additional non-executive employees on the perceptions of ethical culture for a subsample of firms, we encourage future work to measure ethical culture with organizational members at different levels of the organizational hierarchy to corroborate our findings.

Second, although we captured our main measures at different times, we cannot infer causality with our research design. Future research can employ alternative research designs, e.g., experiments, to draw more explicit causal paths between leadership humility and decentralization or ethical behavior outcomes. Future research could also employ longitudinal designs to track the appointment of humble CEOs and subsequent changes in organizational decision-making processes as well as ethical culture. Such changes could be measured at different organizational levels, particularly lower-level employees, to explore the cascading influence of humble CEOs in the organization.

Finally, although our sample considers multiple regions and industries, it is limited to Colombian SMEs. This affects the generalizability of our results. We encourage future researchers to replicate our findings in other countries and samples of large firms. Exploring how our model applies in different cultures can be a particularly important effort. Evidence from research in ethical culture and decision-making agrees on the differences between eastern and western countries. Individuals in collectivistic cultures (more related to Asian nations) tend to abide by company dictates even if those are perceived as unethical, while individuals in individualistic cultures (more related to western countries) tend to follow their own ethical standards (Craft 2013). Additionally, countries with the combination of high-power distance and high individualistic culture, such as Colombia (Botero and Van Dyne 2009; Hofstede 2001; Hofstede et al. 2010), experience stronger influence from peers on ethical decision-making (Westerman et al. (2007). Due to the similarities in ethical cultures of western companies (Ardichvili et al. 2012) and ethical decision-making standards in countries in the Americas (Aguinis et al. 2020; Botero and Van Dyne 2009), it would be important to explore the consistency of our results in other countries in the Americas as well as eastern countries.

Conclusion

Researchers are increasingly interested in exploring how humble CEOs shape organizations through their interactions with other organizational members. However, despite extensive research on how CEOs make decisions that shape organizations, we still have much to learn about the strategic decision-making consequences of humble individuals in the CEO position. Our study contributes to this point by showing that humble CEOs tend to decentralize strategic decisions in their TMT and thus promote an ethical culture in their organizations. We hope that future research continues to explore the role of humble individuals at the top of organizational hierarchies.

Notes

Firms fit the Colombian definition of SMEs, which is based on both the number of employees and assets.

References

Abebe, M. A., Angriawan, A., & Liu, Y. (2011). CEO power and organizational turnaround in declining firms: Does environment play a role? Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 18(2), 260–273.

Aguinis, H., Villamor, I., Lazzarini, S. G., Vassolo, R. S., Amorós, J. E., & Allen, D. G. (2020). Conducting management research in Latin America: Why and what’s in it for you? Journal of Management, 46(5), 615–636.

Aime, F., Humphrey, S., DeRue, D. S., & Paul, J. B. (2014). The riddle of heterarchy: Power transitions in cross-functional teams. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 327–352.

Alexiev, A. S., Jansen, J. J., Van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2010). Top management team advice seeking and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of TMT heterogeneity. Journal of Management Studies, 47(7), 1343–1364.

Amason, A. C. (1996). Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 39(1), 123–148.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Anderson, N. R., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(3), 235–258.

Ardichvili, A., Jondle, D., Kowske, B., Cornachione, E., Li, J., & Thakadipuram, T. (2012). Ethical cultures in large business organizations in Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(4), 415–428.

Ardichvili, A., Mitchell, J. A., & Jondle, D. (2009). Characteristics of ethical business cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 445–451.

Argandona, A. (2015). Humility in management. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(1), 63–71.

Aselage, J., & Eisenberger, R. (2003). Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(5), 491–509.

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 801–823.

Bandura, A. (1969). Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 213–262). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Company.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

Barnett, T., & Schubert, E. (2002). Perceptions of the ethical work climate and covenantal relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 36(3), 279–290.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bauer, T., & Erdogan, B. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of leader–member exchange. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berson, Y., Oreg, S., & Dvir, T. (2008). CEO values, organizational culture and firm outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(5), 615–633.

Boone, C., & Hendriks, W. (2009). Top management team diversity and firm performance: Moderators of functional-background and locus-of-control diversity. Management Science, 55(2), 165–180.

Boone, C., Lokshin, B., Guenter, H., & Belderbos, R. (2019). Top management team nationality diversity, corporate entrepreneurship, and innovation in multinational firms. Strategic Management Journal, 40(2), 277–302.

Botero, I. C., & Van Dyne, L. (2009). Employee voice behavior: Interactive effects of LMX and power distance in the United States and Colombia. Management Communication Quarterly, 23(1), 84–104.

Bromiley, P., & Rau, D. (2016). Social, behavioral, and cognitive influences on upper echelons during strategy process: A literature review. Journal of Management, 42(1), 174–202.

Bromiley, P., & Rau, D. (2016). Missing the point of the practice-based view. Strategic Organization, 14(3), 260–269.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Bunderson, J. S. (2003). Recognizing and utilizing expertise in work groups: A status characteristics perspective. Administrative science quarterly, 48(4), 557–591.

Busenbark, J. R., Krause, R., Boivie, S., & Graffin, S. D. (2016). Toward a configurational perspective on the CEO: A review and synthesis of the management literature. Journal of Management, 42(1), 234–268.

Cao, Q., Simsek, Z., & Zhang, H. (2010). Modelling the joint impact of the CEO and the TMT on organizational ambidexterity. Journal of Management Studies, 47(7), 1272–1296.

Carmeli, A., Schaubroeck, J., & Tishler, A. (2011). How CEO empowering leadership shapes top management team processes: Implications for firm performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 399–411.

Chadegani, A. A., & Jari, A. (2016). Corporate ethical culture: Review of literature and introducing pp model. Procedia Economics and Finance, 36(1), 51–61.

Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2007). It’s all about me: Narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 351–386.

Cialdini, R. B., & De Nicholas, M. E. (1989). Self-presentation by association. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 626–631.

Colbert, A. E., Bono, J. E., & Purvanova, R. K. (2008). Generative leadership in business organizations: Enhancing employee cooperation and well-being through high-quality relationships. In B. A. Sullivan, M. Snyder, & J. L. Sullivan (Eds.), Cooperation: The political psychology of effective human interaction (pp. 199–217). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to great: Why Some Companies Make The Leap—And Others Don’t. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Craft, J. L. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259.

Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychological Reports, 73(2), 667–674.

De Dreu, C. K., & Beersma, B. (2005). Conflict in organizations: Beyond effectiveness and performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14(2), 105–117.

Dehlen, T., Zellweger, T., Kammerlander, N., & Halter, F. (2014). The role of information asymmetry in the choice of entrepreneurial exit routes. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 193–209.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N. E. D., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7–52.

Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B., Jr. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–273.

DeYoung, C. G., Quilty, L. C., & Peterson, J. B. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 880–896.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759.

Eisenbeiss, S. A., Van Knippenberg, D., & Fahrbach, C. M. (2015). Doing well by doing good? Analyzing the relationship between CEO ethical leadership and firm performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 635–651.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Bourgeois, L. J., III. (1988). Politics of strategic decision making in high-velocity environments: Toward a midrange theory. Academy of Management Journal, 31(4), 737–770.

Farrell, K. A., & Winters, D. B. (2008). An analysis of executive compensation in small businesses. The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 12(3), 1–21.