Abstract

We build on limited research concerning the mediation processes associated with the relationship between ethical culture and employee outcomes. A multidimensional measure of ethical culture was examined for its relationship to overall Person-Organization (P–O) fit and employee response, using a sample of 436 employees from social economy and commercial banks in Spain. In line with previous research involving unidimensional measures, ethical culture was found to relate positively to employee job satisfaction, affective commitment, and intention to stay. New to the literature, ethical culture was also found to be associated positively with employee willingness to recommend the organization to others. These effects were observed even when perceptions of P–O fit were controlled. Importantly, ethical culture was also positively related to overall P–O fit, which in turn, partially mediated the relationship between ethical culture and employee outcomes. Our findings add to studies that focus on the importance of the degree of ethical congruence between the individual employee and the organization. They suggest that ethical culture, with its expected impact on virtuousness and emotional well-being, will positively influence outcomes independently of the degree to which there is a match between employee and organizational values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent cases of moral lapses and scandals in business, e.g., the resignation of Brian Dunn, CEO of Best Buy (Bustillo 2012) have heightened the importance of ethics as an aid to the long-term viability of businesses and to global social welfare. The development of virtues and the practice of ethics can have a variety of positive consequences for business organizations (Cameron et al. 2004) fueling the need to better understand how organizational ethics and positive employee outcomes are connected.

The relationship between organizational ethics and employee response has been documented over the last decade. For example, Brown and Treviño (2006) provided important theoretical rationale for empirical studies linking ethical leadership to employee attitudes and behavior (Mayer et al. 2009; Neubert et al. 2009; Toor and Ofori 2009). Ethical leadership is one component of ethical culture, which O’Fallon and Butterfield (2005, p. 400) highlighted as a topic of growing research interest. Indeed, since their review, there have been a number of studies linking ethical culture measures to a variety of employee outcomes (Mulki et al. 2006, 2008; Pettijohn et al. 2008; Rego et al. 2010; Valentine et al. 2006, 2011).

Although there has been an increase in research concerning ethical culture and employee response, most of it has employed short one-dimensional measures of ethical culture. Since, as noted by Valentine et al. (2011, p. 355), companies can use a variety of different approaches to build ethical context, in this study, we employ a multidimensional assessment of ethical culture and examine its relationship to job satisfaction, affective commitment, intent to stay, and willingness to recommend the organization to others. Our examination of willingness to recommend (Cable and Judge 1996), a first in the ethics literature, is important because employee referral is widely regarded to be the single most effective recruiting method (Breaugh 2008). As such, willingness to recommend can help employers identify talent (Michaels et al. 2001). Even in a challenging economy, many businesses vigorously compete for the best possible employees (War for Talent 2012).

Another relatively unaddressed issue in the literature concerns the nature of the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between ethical culture and employee outcomes (Mulki et al. 2008). Accordingly, we add to the literature by evaluating the possibility that overall Person-Organization (P–O) fit (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005) partially mediates the relationship between ethical culture and employee response. Although the relevance of perceived differences in ethicality between employees and their organizations has been demonstrated in relation to employee outcomes (e.g., Ambrose et al. 2008; Sims and Keon 1997; Sims and Keon 2000; Sims and Kroeck 1994; Thorne 2010), we are interested in the role of overall P–O fit (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005).

Finally, almost all the research concerning ethical culture, P–O fit and employee response has been conducted in North America. In this study, however, we sample employees from commercial and social economy banks in Spain. As we will explain, these banks differ in their overall missions in ways that may impact ethical behavior. Moreover, our choice of Spain reflects the fact that ethics-related findings cannot simply be assumed to generalize across national cultures (Valentine and Rittenburg 2004). As such, two especially interesting contextual variables (Johns 2006) are imbedded within our investigation.

Theoretical Framework

Organizational Culture, Ethical Culture, Ethical Context, and Employee Job Outcomes

From the perspective of resource-based theory, human resources are strategic to the optimal operation of the organization (Wright et al. 1994). For example, employee knowledge, competencies and intellectual capital have the potential to contribute to sustained competitive advantage (De Saá-Pérez and García-Falcón 2002). Nonetheless, to take full advantage of this potential, business must attend to a full range of motivational variables including contextual factors, such as organizational culture (De Saá-Pérez and García-Falcón 2002). Organizational culture, often described in terms of shared values, beliefs, and assumptions (Schein 1992) can energize employees (Chatman and Eunyoung Cha 2003) by for example, supporting ethics and virtuous behavior (Cameron et al. 2004), which may, in turn, enhance a variety of employee and organizational outcomes.

As a subset of organizational culture, ethical culture can be viewed as resulting from the interplay among the formal (e.g., training efforts, codes of ethics) and informal (e.g., peer behavior, norms concerning ethics) systems that potentially enhance the ethical behavior among employees (Treviño et al. 1998). Ethical culture can also be distinguished from the Victor and Cullen (1988) conceptualization of ethical climate (Martin and Cullen 2006), which, for example, does not necessarily translate into clear guidelines for what constitutes ethical behavior (Treviño et al. 1998). In any case, measures of ethical culture and climate are strongly related such that they can be subsumed under the rubric of ethical context (Treviño et al. 1998).

From an Aristotelian perspective, a culture supportive of ethics allows for virtuous actions reflective of the potential for human excellence (Ciulla 2004; Guillén 2006). Values, assumptions and beliefs transmitted through ethical cultures are of a moral nature, goods in themselves, whose fulfillment facilitates happiness, which Aristotle considers as the end to which human beings aim in life (Ciulla 2004). Thus, when moral virtuousness is experienced in human relationships, employees likely feel more appreciated, loved, and well treated (Argandoña 2011), which is positive for both their emotional state and job outcomes (Cameron et al. 2004; Rego et al. 2010). Since ethics and moral virtuousness is so intimately linked to excellence and perfection in human action (Argandoña 2011; Melé 2009), the theoretical basis for expecting a relationship between ethical culture and positive employee emotions and attitudes is a strong one.

Indeed, some empirical studies have linked the Hunt et al. (1989) scale of corporate ethical values to job satisfaction (Pettijohn et al. 2008; Valentine et al. 2011), organizational commitment (Hunt et al. 1989; Sharma et al. 2009; Valentine et al. 2002), and turnover intentions (Pettijohn et al. 2008; Valentine et al. 2011). Schwepker’s (2001) measure of ethical climate is also variously associated with job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intent to turnover (Jaramillo et al. 2006; Mulki et al. 2006, 2008; 2009; Schwepker 2001; Weeks et al. 2004).

Both the five-item Hunt et al. (1989) scale and the seven-item Schwepker (2001) measures are relatively short, single dimension assessments of ethical context. As such, they do not address many of the components (e.g., ethics training, rewards system, and peer and top management behavior) considered to be essential elements of an ethical culture (Treviño et al. 1998). By focusing mainly upon the presence and enforcement of ethics codes and policies, Schwepker (2001, p. 49) noted the need for further research to determine if multidimensional assessments of the ethics context are more strongly related to employee outcomes.

The multidimensional measure of ethical culture in this study, like Schwepker (2001), addresses the presence and enforcement of ethical codes and policies, but adds content involving supervisor ethical behavior (Brown et al. 2005), ethics training, the degree to which ethics is tied to the performance system, as well as more detail concerning the ethical behavior of peers and top management. As such, it is broader than both the Hunt et al. (1989) and Schwepker (2001) scales.

Given the theory presented earlier and the previous findings relating employee outcomes to organizational ethics and to ethical culture perceptions, we expect ethical culture to associate positively with a range of employee attitudes and intentions, including willingness to recommend the organization to others as a good place to work. Although willingness to recommend has not been studied in relation to ethical culture, a positive relationship would be expected to the extent that employees prefer ethical environments (e.g., Coldwell et al. 2008; Treviño and Nelson 2004), and to the extent that they tend to recommend organizations that participate actively in social responsibility activities (i.e., support to local communities, environmental protection) (Kenexa Research Institute 2010; Harvey et al. 2010). Thus:

Hypothesis 1

Ethical culture is directly and positively related to employee job satisfaction, affective commitment, intention to stay, and willingness to recommend the organization to others.

P–O Fit and Employee Job Outcomes

As an application of the Person-environment perspective in organizational settings (Terborg 1981), P–O fit has typically been conceptualized as the degree of congruence between employee and organizational beliefs, norms, values (Chatman 1989), and goals (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). The importance attached to the degree of P–O fit is in line with various theoretical frameworks, including the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957) that, as applied to the work environment, states that in those situations in which an employee perceives a meaningful discrepancy between their norms and values and those of the company, dissonance perceived would be reflected in poor work attitudes (Koh and Boo 2001; Viswesvaran et al. 1998) and feelings (Bande-Vilela et al. 2008). Indeed, various measures of perceived differences in ethicality between employees and their organizations are positively related to feelings of discomfort, interpersonal role conflict (Sims and Keon 2000), and turnover intentions (Ambrose et al. 2008; Sims and Keon 1997; Sims and Kroeck 1994; Thorne 2010), but negatively related to job satisfaction (Sims and Keon 1997) and organizational commitment (Ambrose et al. 2008; Sims and Kroeck 1994; Thorne 2010). On the other hand, a high degree of overall P–O fit has the potential to satisfy human needs, desires and preferences (Chatman 1989; Kristof 1996) generating positive subjective experiences (Bande-Vilela et al. 2008) and a willingness to recommend the organization to others (Cable and Judge 1996). Though studies specific to Spain are few (e.g., Bande-Vilela et al. 2008), meta-analytic work has established that direct overall perceived measures of P–O fit are related to a variety of job outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intent to leave) (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Verquer et al. 2003). Thus:

Hypothesis 2

P–O fit is directly and positively related to employee job satisfaction, affective commitment, intention to stay, and willingness to recommend the organization to others.

Ethical Culture and Employee Job Outcomes: The Mediating Role of P–O Fit

While considerable research has focused on the relationship of P–O fit to employee outcomes (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Verquer et al. 2003) there is a need to understand the mechanisms that underlie P–O fit (Kristof 1996). For example, Attraction-Selection-Attrition theory (Schneider 1987) proposes that various human resources practices (i.e., recruitment, selection, etc.) yield cues used by applicants to make inferences concerning the degree of similarity between themselves and the organization. As such, the job choice process can be considered major antecedent of P–O fit (Adkins et al. 1994; Cable and Judge 1994, 1996; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005).

Once applicants join an organization, there are many post-entry variables that could influence fit. For example, Valentine et al. (2002) hypothesized and found a positive relationship between the Hunt et al. (1989) corporate ethical values scale and P–O Fit. Their thinking was based on the expectations of reciprocity employees have for their employers (Kristof 1996) and more broadly, on the psychological contract. Psychological contracts (Rousseau 1995) are operative when employees form beliefs concerning the terms and conditions of the exchange (i.e., reciprocal promises, commitments, and obligations) between themselves and their organizations. In pointing out that employees are attracted to and commonly prefer ethical environments (e.g., Coldwell et al. 2008; Treviño and Nelson 2004), Valentine et al. (2002) argued that by supporting ethical conduct, employers could strengthen the psychological contract. For example, an ethical culture is linked to perceptions of justice and fairness in organizational decisions (Ardichvili et al. 2009; Weaver and Treviño 2001) which fosters the formation of relational contracts based on social exchange (Barnett and Schubert 2002; Rego et al. 2010). Ethical culture also supports long-term, supportive open-ended collaborations (Aselage and Eisenberger 2003) including covenantal relationships based on mutual commitments to the welfare of both parties (employee-organization) and collective agreements concerning acceptable attitudes, behaviors, and values (Barnett and Schubert 2002).

The Valentine et al. (2002) finding and related theory provide some confidence that our multidimensional assessment of culture will be related to P–O fit. Nonetheless, two of the four items in the Valentine et al. (2002) measure of P–O fit refer explicitly to ethics-related issues (honesty and fairness). In contrast, our interest is in overall P–O Fit. Thus:

Hypothesis 3

Ethical culture is directly and positively related to overall P–O Fit.

The third hypothesis in conjunction with the second one (that P–O fit relates positively to job outcomes) is consistent with the possibility that P–O fit mediates the association between ethical culture and job outcomes. Though this mediation effect has not yet been empirically tested, the notion is consistent with studies involving other mediators of the ethical culture-employee outcomes relationship. For example, Valentine et al. (2006) found that perceived organizational support—a likely positive contributor to P–O Fit (Darnold et al. 2005)—partially mediated the link between ethical culture, and both job satisfaction and turnover intent. The effect was expected based partly on the idea that perceptions of justice and fairness associated with efforts to enhance ethical culture would positively impact employee beliefs central to perceived organizational support, i.e., the degree to which employee contributions are valued, and the extent to which the organization is concerned about employee well-being (Valentine et al. 2006). Kaptein (2008), subsequently, concluded that supportability is one of the virtues on which an ethical culture is built up. Also, Sharma et al. (2009) found that perceived fairness moderated the relationship between ethical culture and organizational commitment. Further, since employees are exposed to virtuousness and encouraged to develop it in ethical cultures (Kaptein 2008; Melé 2009), there is the potential to build intraorganizational social capital, facilitating communication, cooperation and strong relationships (Cameron et al. 2004), resulting in attachment and attraction to virtuous actors (Bolino et al. 2002), all of which should ultimately facilitate shared frameworks of reference (Granitz 2003) thought to enhance P–O fit.

Also consistent with the potential mediating role of P–O fit, both Jaramillo et al. (2006) and Mulki et al. (2008) found that role stress (role conflict and role ambiguity) partially mediated the relationship between ethical culture and turnover intent. This is important because strain tends to relate negatively to P–O fit (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). Since our multidimensional measure of ethical culture has components both likely to be most directly experienced through the job (e.g., supervisory ethical leadership, peer behavior) and through the organization (e.g., top management ethics, ethical conduct considered in performance evaluations, and ethics codes), it is likely that the combination of mechanisms will be reflected in our direct perceived measure of overall P–O fit. Thus:

Hypothesis 4

The relationship between ethical culture and job satisfaction, affective commitment, intention to stay, and willingness to recommend the organization, is partially mediated by P–O fit.

Study Setting: National Culture and Banking Mission

As noted earlier, almost all of the literature concerning the variables of interest in this study is based in North America. As such, our use of bank employees from Spain is of specific interest. Variation in national cultures can affect how employers should approach ethical issues (Guillén et al. 2002), due to differences employee sensitivity to them and to differences in the level of tolerance people have for unethical behavior (Collins 2000). For example, Valentine and Rittenburg (2004) found that executives from the U.S. and Spain differed in their levels of ethical intent. Also, in comparing findings from Spain to the U.S., Vitell and Ramos (2006) found significant differences in corporate ethical values and organizational commitment, among other variables.

Finally, a unique aspect of our study setting is that we sample employees from both social economy and traditional commercial banks. The former includes savings and credit union entities with business models that encompass the broader social interest, as opposed to the narrower purely financial focus of commercial banking; they also typically have stronger corporate social responsibility practices (Sanchis and Campos 2008). Since differences in job attitudes and behavior can exist depending on the degree to which the company regarded to be socially responsible (Kenexa Research Institute 2010; Treviño and Nelson 2004; Valentine and Fleischman 2008), this contextual variable (Johns 2006) is of obvious interest.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Following pilot testing (n = 38), a survey was distributed to 4,164 employees at large branches/offices (generally those with 4 or more employees) of various commercial, savings, and credit union banking entities in five Spanish provinces. Questionnaires were typically distributed directly to employees after gaining consent of the branch manager; alternatively they were mailed to employees upon the approval of a regional director. The sample of locations was a broad one. After excluding temporary employees and those who had been with the company for less than a year, 436 surveys were useable. The response rate (10.5 %) was good given the sensitivity of the ethics content and that employees from many different locations were surveyed (Valentine et al. 2006).

In order to minimize valuation apprehension and to decrease social desirability bias, a cover letter was included emphasizing that there were no right or wrong answers. Material on the questionnaire itself also guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. Among those who responded to the gender item, 46.3 % were male (26 % left the gender item blank). Approximately half the sample was under 40 years old. The educational level was relatively high (65 % had college degrees), with 60 % having been with the organization for more than 10 years.

In order to evaluate the possibility of nonresponse bias, the first quartile and last quartile of submissions were compared under the assumption that late respondents were more similar to nonrespondents than early ones (Armstrong and Overton 1977). Independent sample t-tests did not reveal any significant differences in the study variables lessening the possibility of non response bias.

Measures

When measures are used to examine a latent construct, a choice between reflective or formative indicators must be made (MacKenzie et al. 2005; Podsakoff et al. 2006). Reflective measurements, commonly recommended when personality and attitudinal variables are modeled (Mackenzie et al. 2005) are highly correlated indicators thought to be caused by a targeted latent construct. Formative measures, on the other hand, involve indicators that may determine the construct without necessarily being highly correlated (Chin 1998; MacKenzie et al. 2005) such that traditional reliability and validity criteria may be inappropriate and irrelevant (Henseler et al. 2009).

Using Mackenzie et al.’s (2005) criteria for distinguishing between reflective and formative constructs, our survey contained both reflective and formative variables, including a second-order (Mackenzie et al. 2005; Podsakoff et al. 2006) formative construct (ethical culture, see below) composed of multiple first-order structures.

Unless otherwise noted, all measures used a five-point response format (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Negatively worded items were reverse scored for the purposes of the analyses.

Ethical culture. Four first-order variables (top management ethical leadership, supervisor ethical leadership, peers ethical behavior, and formal ethics policy), each traditionally viewed as important formative components of the ethical context, were assessed.

Top management ethical leadership (TMEL). Three reflective items adapted from previous research (Koh and Boo 2001; Treviño et al. 1998; Treviño and Weaver 2001) were used, including, “The top manager in my organization is a model of ethical behavior” and “Generally, top management treats their employees fairly”.

Supervisor ethical leadership (SEL) was measured using the Brown et al. (2005) ten-item reflective scale (e.g., “My superior conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner”).

Peers ethical behavior (PEB) was assessed using three formative items (1 = never, 5 = very often) adapted from previous research (Izraeli 1988; Treviño and Weaver 2001; Vardi 2001; Peterson 2004) and which, as in Peterson (2004), encompassed a variety of possible ethical failures (i.e., misuse of work-time, harassment, and deceit) with direct implications for the company, co-workers, and customers, respectively.

Formal policy on ethics (FPE) was measured by three formative items covering some of the most commonly used ethics enhancing initiatives in this geography (Guillén et al. 2002; Fontrodona and de los Santos 2004), i.e., the presence of a formal code of ethics, ethics-training efforts and the degree to which ethical behavior is tied to the performance management system (e.g., ‘My behavior’s morality is considered when my job performance is assessed’).

Job Satisfaction (JS). Three reflective items from the Overall Job Satisfaction Scale (Seashore et al. 1982) were used (e.g., “All in all, I am satisfied with my job”).

Affective Commitment (AC). As in Moideenkutty et al. (2001), three reflective items from the Allen and Meyer (1990) affective commitment scale were used (e.g., “I feel a strong sense of belonging to this organization”).

Intention to Stay (IS). Based on Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) and Randall et al. (1999), three items were adapted (e.g., “I intend to remain with this organization indefinitely” and “I often think about quitting this organization”; reverse scored).

Willingness to Recommend the organization (WR). The two item scale from Cable and Judge (1996) was used (e.g., “I would tell my friends not to work for this organization”; reverse scored).

P–O Fit. The reflective three-item scale of overall fit from Cable and Judge (1996) was adapted (e.g., “My values match those of the current employees in the organization”).

Control Variables

Education, bank sector, and age were controlled given their potential impact on attitudes (e.g., Cohen and Avrahami 2006; Linz 2003; Mathieu and Zajac 1990; Valentine and Fleischman 2008). Dummy coded variables were created for education (0 = no college, 1 = college) and bank sector (0 = Commercial Banking, 1 = Social Economy Banking). The association of these variables with other indices must be understood relative to the excluded referent category in the analysis, “no college”, and “commercial banking”, respectively (Falk and Miller 1992).

Though the problem is often overstated (Spector 2006), common method variance was a potential concern in this study because the same respondent provided the data for both the independent and dependent variables. As such, some of the Podsakoff et al. (2003) procedural remedies were used. First, a psychological separation between predictors and criterion variables to make them appear to be unrelated was established by grouping questions under different general topic areas. Second, various situational and personality constructs were included in the questionnaire and served as distracters. Third, the dependent variables appeared in the questionnaire prior to the ethics-related predictors. As noted earlier, the importance of frankness was emphasized as was anonymity of the responses. Finally, questionnaire items were carefully chosen to be simple, specific, and concise.

Data Analysis

SPSS 19.0 was used to generate descriptive statistics and to conduct an exploratory factor analysis to evaluate the possibility of common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Partial least squares (PLS)-Graph 3.00 (Chin 2003) was used to test the hypotheses. PLS is a powerful and robust statistical procedure (Chin et al. 2003; Henseler et al. 2009) that allows for causal analysis in situations of high complexity (Henseler et al. 2009). As a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, it is well suited to test mediation hypotheses (James et al. 2006). Further, PLS does not require demanding assumptions regarding the distribution of the variables (Henseler et al. 2009) and is the only SEM technique that allows the inclusion of both reflective and formative measures in the same analysis (Chin 1998; Henseler et al. 2009). Bootstrapping (500 resamples) was used to generate standard errors and t-statistics for hypotheses testing (Chin 1998).

Results

Common Method Variance

In order to assess the extent of common method variance in the data, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted. Harman’s one factor test revealed eight factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, accounting for 66 % of the variance in the data. As the first factor explained only the 30 % of the total variance, it is less likely that our findings can be attributed to method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

Measurement Model

Evidence supporting the individual reliability, construct reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity of all the reflective latent variables (Henseler et al. 2009) is shown in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 also includes indices supporting the effective measurement of both the first and second-order formative constructs. Finally, correlations among the constructs are reflected in Table 2.

As shown in Table 1, the reliability of individual items comprising the reflective constructs (TMEL, SEL, JS, AC, IS, WR and P–O Fit) was considered adequate since their standardized loadings were generally higher than the minimally acceptable value of 0.55 (Falk and Miller 1992) and typically above the desired 0.70 (Henseler et al. 2009). Though the loading for SEL4 was low (0.45), the item was retained because it was part of a well-researched scale and its inclusion did not adversely affect any of the other SEL measurement criteria. Thus, the composite reliabilities (Werts et al. 1974) were 0.80 or better (Nunnally 1978) while the average variance extracted exceeded 0.50, supporting convergent validity (Henseler et al. 2009).

In support of discriminant validity, Table 2 shows that the average variance extracted for each of the reflective constructs is greater than the variance shared with the remaining constructs (Henseler et al. 2009). Also, the indicators of the various measures loaded more heavily on their intended constructs than on the others (Henseler et al. 2009).

Tests for multicollinearity involving both indicators of the first and second order formative variables revealed minimal collinearity, as the respective variance inflation factors (VIF) ranged between 1.06 and 1.38 (see Table 1), far below the common cut-off threshold of 5–10 (Kleinbaum et al. 1998). As noted earlier (see Table 1) all of the indicators associated with the first-order formative constructs were significant. Further, all of the intended first-order constructs significantly contributed to the second-order formative ethical culture construct ultimately used in the analysis.

Control Variables

As explained earlier, education, banking sector, and age were each examined for their potential influence on the dependent variables in this study. There were some significant effects (see Table 3). For example, with regard to affective commitment, consistent with previous research (Mathieu and Zajac 1990; Mowday et al. 1982) highly educated employees tended to be less committed to their organizations (β = −0.10, p < 0.05). Perhaps those with more education want more in the way of rewards from their employers (Joiner and Bakalis 2006) and have higher expectations generally (Mowday et al. 1982). Affective commitment was also lower among employees in traditional commercial banking, relative to saving banks and credit unions (β = 0.10, p < 0.05). This finding may reflect the differences between commercial banking and social economy banking in social responsibility and performance criteria. As explained earlier, social economy banking missions have broader social content (solidarity and satisfaction of general interests) as well as stronger corporate social responsibility practices (Sanchis and Campos 2008). Since better social performance associates positively with job attitudes (Kenexa Research Institute 2010; Treviño and Nelson 2004; Valentine and Fleischman 2008) this may account for the enhanced commitment in social economy banking.

With regard to intent to stay and willingness to recommend the organization, the social economy banks also enjoyed a slight advantage relative to commercial banking (β = 0.07, p < 0.10 for intent to stay; β = 0.19, p < 0.001 for willingness to recommend). These findings likely reflect dynamics similar to those explained above with regard to commitment. Finally, consistent with previous research (Cohen and Golan 2007) intention to stay was also positively related to age (β = 0.16, p < 0.01). Older employees typically have more invested in their organizations (e.g., accumulated pay increases and retirement benefits; Cohen and Golan 2007) and often have relatively limited alternative employment options, both of which make it more likely that they will stay.

Hypothesis Testing

Table 4 shows the findings related to our specific hypotheses. As anticipated, hypothesis H1 was supported in that ethical culture was directed and positively related to job satisfaction (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), affective commitment (β = 0.17, p < 0.001), intent to stay (β = 0.12, p < 0.05), and willingness to recommend the organization to others (β = 0.34, p < 0.001). P–O fit was also positively and directly related to each of these variables (β = 0.26; p < 0.001 for job satisfaction; β = 0.54; p < 0.001 for affective commitment; β = 0.36; p < 0.001 for intent to stay; and β = 0.33; p < 0.001 for willingness to recommend), thus supporting hypothesis H2. In line with H3, ethical culture was directly and positively related to P–O fit (β = 0.56, p < 0.001).

Table 4 also shows evidence consistent with H4, that P–O fit partially mediates the relationship between ethical culture and the dependent variables. Specifically, in line with the Preacher and Hayes (2004, 2008) guidelines, note the significant indirect effects involving ethical culture and job satisfaction (b = 0.15; p < 0.01), affective commitment (b = 0.30; p < 0.01), intention to stay (b = 0.20; p < 0.01), and intent to recommend the organization to others (b = 0.18; p < 0.01).

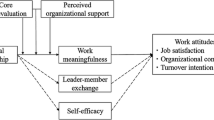

In order to more comprehensively examine H4, the Tippins and Sohi (2003) four step procedure was also used. It includes the Baron and Kenny criteria (1986) for evaluating mediation effects, but is more applicable to SEM because it involves the comparison of a direct model to a mediated one (see Fig. 1, Models A and B). The first condition is met since ethical culture is significantly related to job satisfaction, affective commitment, intention to stay, and willingness to recommend (see Fig. 1, Model A). The second requirement was also satisfied; P–O fit is directly and positively related to the dependent variables (see Fig. 1, Model B). Regarding the third requirement, when P–O fit is included as mediator, the magnitude of the direct influence between ethical culture and each of the dependent variables is diminished (see Fig. 1; Model A βEC coefficients for H1, versus Model B, βEC coefficients for H1). Support for the fourth criterion was attained since the partial mediated model accounted for more variance in each of the dependent variables than the direct one (see Fig. 1, Model A vs B). Thus, H4 concerning the mediating effect of P–O fit was supported using a variety of criteria (Baron and Kenny 1986; Preacher and Hayes 2004, 2008; Tippins and Sohi 2003). Finally, Table 5 shows that the increase in variance accounted for reflected different mediation effect sizes: weak for job satisfaction (f 2 = 0.03), strong for affective commitment (f 2 = 0.37), and weak-moderate for both intentions to stay (f 2 = 0.10) and willingness to recommend (f 2 = 0.13) (Chin 1998).

The mediating role of P–O fit: comparative analysis of models. Model A Structural model incorporating direct effects. Model B Structural model incorporating the P–O fit mediation effect Notes: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (based on a Student t (499) one-tailed test): t (0.001;499) = 3.11; t (0.01;499) = 2.33 and t (0.05;499) = 1.65. Though not depicted in the Figure, the total variance accounted for all job outcome variables includes small effects associated with some of the control variables (see Table 3)

Discussion and Conclusions

Contributions to Scholarship

A comprehensive multidimensional measure was used to examine the relationship of ethical culture to overall P–O fit and employee response. Willingness to recommend the organization to others was shown to be positively related to ethical culture, as were job satisfaction, affective organizational commitment, and intent to stay. Importantly, all of these relationships were observed even when perceptions of overall P–O fit were controlled. Moreover, P–O fit partially mediated the relationship between ethical culture and each of the outcome variables.

This is the first study to investigate P–O fit as a mediator of the relationship between ethical culture and employee outcomes. As such, there are several contributions to the literature. First, the use of a multidimensional measure of ethical culture in relation to employee response is unusual in that one-dimensional assessments (Hunt et al. 1989; Schwepker 2001) have typically been employed. Existing findings, relating unidimensional measures of ethical culture to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intent to stay, were generally comparable in magnitude to our multidimensional assessment. These findings are consistent with the notion that employees have only a global impression of ethical culture, and reflect the Treviño et al. (1998) conclusion that even multidimensional assessments of ethical culture and climate are strongly related.

The link between ethical culture and employee response, even after P–O fit is controlled, is interesting because it implies that ethical culture enhances outcomes independently of the degree of ethicality and/or the specific values of individual employees. This is in line with research suggesting that in positively affecting job outcomes, perceptions of organizational ethical values are more important than the perceived degree of P–O ethical fit (Finegan 2000; Herrbach and Mignonac 2007; Schminke et al. 2005). Thus, our findings are an important addition to research linking measures of the perceived differences in ethicality between employees and their organizations to feelings of discomfort, interpersonal role conflict (Sims and Keon 2000), and turnover intentions (Ambrose et al. 2008; Sims and Keon 1997; Sims and Kroeck 1994; Thorne 2010), among other work outcomes.

The positive association between our multidimensional measure of ethical culture and perceived overall P–O fit is significant because, unlike Valentine et al. (2002), the link is demonstrated even though our measure of fit is global and contains no reference to ethical issues. Moreover, in answering the call to further investigate ethical context in relation to P–O fit (e.g., Ambrose et al. 2008), we are the first to demonstrate that P–O fit partially mediates the relationship between ethical culture and employee response. Since direct perceived measures of P–O and P–J fit are strongly related (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005), this implies that ethical culture components can have a positive influence at a variety of different levels. Thus, it is not surprising that both organizational (perceived organizational support; Valentine et al. 2006) and job-related (e.g., role ambiguity and role conflict; Jaramillo et al. 2006; Mulki et al. 2008) variables have been found to mediate the association between ethical culture and employee outcomes. Other possible mediators await future research, including happiness (Rego et al. 2010) and processes related to psychological contracts (Rousseau 1995), such as perceived fairness (Sharma et al. 2009).

Applied Implications

The potential strategic value of the human resources at a firm is recognized both in the academic (Wright et al. 1994) and practitioner spheres (Deloitte 2010a). Nonetheless, the claim and belief that people constitute an important strategic asset does not always translate into management practices reflecting a serious commitment to employee needs (Hodson 2004). Our results are consistent with the notion that exposure to positive ethical contexts can enhance both job attitudes and affective well-being (Rego et al. 2010; Valentine et al. 2011) which can satisfy needs and raise overall morale. Specifically, endorsing ethics through the organizational culture is a potentially useful way to keep (good) employees satisfied, committed, and willing to stay, all of which are likely consequences of the establishment of good, successful trust-based human relationships (Hunter 1998; Kouzes and Posner 2001). Further, our finding that ethical culture is positively related to the intent to recommend the organization to others is very important because, as noted earlier, employee referrals are generally regarded as the single most effective recruiting method (Breaugh 2008). Thus, positive word of mouth from existing employees has the potential to be a significant advantage in war for talent (Michaels et al. 2001; War for Talent 2012). Finally, recent surveys (e.g., Deloitte 2010b) support the applied importance of building ethical cultures since indicators of poor ethical business practices (i.e., low trust in employers and/or a lack of transparency from employers) are among the important antecedents of negative job outcomes, such as turnover.

Our findings suggest that management efforts should be heavily focused on creating an ethical culture, since it is likely that the effects will be felt irrespective of the personal tendencies of individual employees. Indeed, efforts to build an ethical culture appear to be well placed relative to initiatives (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Verquer et al. 2003) aimed simply at finding employees with values and expectations that match those of the organization. Certainly, it is likely that employees will feel uncomfortable in firms where decisions and rewards are based on ethical reasoning inconsistent with their own (e.g., Sims and Keon 1997; 2000). Nonetheless, since many people strive to enhance their moral development and are attracted to others perceived to apply high levels of ethical reasoning (Rest et al. 1999; Schminke et al. 2005), developing an ethical culture has the potential to enhance the emotional psychological states and well-being of all employees (Cameron et al. 2004; Rego et al. 2010). Higher P–O fit perceptions may thus be a direct positive consequence of a strong ethical culture (Coldwell et al. 2008; Valentine et al. 2002) wherein, for example, strong relational and covenantal contracts are both formed and maintained (Barnett and Schubert 2002). These advantages could be self sustaining to the extent that applicants wishing to work in organizations similar to themselves accurately perceive the culture during the selection process (Cable and Judge 1996).

Of course, building an ethical culture is neither easy nor immediate in that it requires dedicated long-term effort on many fronts. Since company assumptions, values and beliefs must be communicated in ways that are widely perceived (Schein 1992) the initiatives cannot simply be limited to formal explicit instruments (e.g., codes of ethics) as these may be viewed as window-dressing (Treviño and Brown 2004; Treviño and Weaver 2001) and may fail to impact the daily experiences of employees (Herrbach and Mignonac 2007). More informal and implicit messages, such as those reflected by leader and peer role modeling are also necessary to successfully build a rooted culture (Herrbach and Mignonac 2007; Treviño and Brown 2004). Further, incongruence among the various organizational systems must be avoided (Kolodinsky 2006; Treviño and Brown 2004; Treviño and Nelson 2004). Finally, the practice of moral virtues is required as it provides sustained attitudes and interior strength (Melé 2005), the foundation needed for ethical behavior to become natural (Hartman 1998). Thus, as reflected by our ethical culture measure, the on-going display of moral virtuous behavior by top management, supervisors and peers, combined with formal ethics mechanisms are required to build a strong ethical culture.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study was cross-sectional which does not allow for the stronger causal inferences of longitudinal designs. Also, broad generalizations of the findings must be made with caution given the specific industry sector (banking) and cultural context (Spain) involved. On the other hand, our findings are quite robust; the hypotheses were supported despite the cultural differences between Spain and North America (e.g., Gupta et al. 2002; Valentine and Rittenburg 2004; Vitell and Ramos 2006). Further, our other important contextual variable, commercial versus social economy banking, accounted for only small differences in a few variables, and did not alter the applicability of the overall model.

Other limitations include the use of single source data and the lack of an explicit measure of social desirability bias. As described earlier, some procedural and analytical remedies (Podsakoff et al. 2003) were employed to address these problems. Also, it should be noted that in at least two studies (see Valentine et al. 2011), social desirability was typically unrelated to ethical culture, job satisfaction and turnover intent. Perhaps, the use of short assessments of social desirability (Deshpande et al. 2006) represents a good compromise.

Given the small number of studies involving ethical culture, P–O fit and employee outcomes, several unresolved issues remain. For example, although we conceived of them as separate outcomes, others (e.g., Schwepker 2001) have treated job satisfaction as an antecedent of organizational commitment. Also, differing from our view, Valentine et al. (2002, p. 352) suggested that organizational commitment was an antecedent to P–O Fit, though much of their reasoning was also consistent with the notion of a reciprocal relationship.

There is a need to examine a wider range of employee and organizational outcomes in relation to ethical culture and P–O fit. For example, although we used intent to stay, the link between intentions and actual behavior (in this case, turnover) is often not as strong as commonly assumed (Dalton et al. 1999). Indeed, meta-analysis reveals a much weaker, less generalizable relationship involving P–O fit and actual turnover (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005).

In terms of other types of performance, Valentine et al. (2011) found corporate ethical values to be positively related to creativity. Adding P–O fit to their study would be interesting since these perceptions can be negatively related to creativity due to their implications for workforce homogeneity (Schneider et al. 1998). Finally, there are few studies relating ethical culture to job performance, and most of them use self-reported indices as opposed to supervisory ratings. In any case, ethical culture has been found to be indirectly linked to performance ratings (e.g., Jaramillo et al. 2006; Mulki et al. 2009; Sharma et al. 2009), but P–O Fit was not part of these investigations.

References

Adkins, C. L., Russell, C. J., & Werbel, J. D. (1994). Judgments of fit in the selection process: The role of work value congruence. Personnel Psychology, 47(3), 605–623.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

Ambrose, M. L., Arnaud, A., & Schminke, M. (2008). Individual moral development and ethical climate: The influence of Person-organization fit on job attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 77, 323–333.

Ardichvili, A., Mitchell, J. A., & Jondle, D. (2009). Characteristics of ethical business cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 445–451.

Argandoña, A. (2011). Beyond contracts: Love in firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 99, 77–85.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating non response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–403.

Aselage, J., & Eisenberger, R. (2003). Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 24(5), 491–509.

Bande-Vilela, B., Varela-Gonzalez, J. A., & Fernandez-Ferrín, P. (2008). Person-organization fit, OCB and performance appraisal: Evidence from matched supervisor-salesperson data set in a Spanish context. Industrial Marketing Management, 37, 1005–1019.

Barnett, T., & Schubert, E. (2002). Perceptions of the ethical work climate and covenantal relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 36, 279–290.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bolino, M., Turnley, W., & Bloodgood, J. (2002). Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 27(4), 505–522.

Breaugh, J. A. (2008). Employee recruitment: Current knowledge and important areas for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 18, 103–118.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Bustillo, M. (2012) Best buy CEO quits in probe. The Wall Street Journal.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Pay preferences and job search decisions: A Person organization fit perspective. Personnel Psychology, 47, 317–348.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person-organization fit, job choice decisions and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67, 294–311.

Cameron, K., Bright, D., & Caza, A. (2004). Exploring the relationships between organizational virtuousness and performance. American Behavioural Scientist, 47(6), 1–24.

Chatman, J. (1989). Improving interactional organizational research: A model of Person-organization fit. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 333–349.

Chatman, J. A., & Eunyoung Cha, S. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45, 19–34.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chin, W.W. (2003) PLS-Graph, Version 3.00 (Build 1130), University of Houston, TX.

Chin, W.W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003) A partial least squares latent variable modelling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2), 189–217.

Ciulla, J. B. (2004). Ethics and leadership effectiveness. In J. Antonakis, A. T. Cianciolo, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The nature of leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Cohen, A., & Avrahami, A. (2006). The relationship between individualism, collectivism, the perception of justice, demographic characteristics and organisational citizenship behaviour. The Service Industries Journal, 26(8), 889–901.

Cohen, A., & Golan, R. (2007). Predicting absenteeism and turnover intentions by past absenteeism and work attitudes: An empirical examination of female employees in long term nursing care facilities. Career Development International, 12(5), 416–432.

Coldwell, D., Billsberry, J., Meurs, N., & Marsh, P. (2008). The effects of Person-organization ethical fit on employee attraction and retention: Towards a testable explanatory model. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(4), 611–622.

Collins, D. (2000). The quest to improve the human condition. Journal of Business Ethics, 26, 1–73.

Dalton, D. R., Johnson, J. L., & Daily, C. M. (1999). On the use of “Intent to…” variables in organizational research: An empirical and cautionary assessment. Human Relations, 52(10), 1337–1350.

Darnold, T. C., Kristof-Brown, A., & Shore, L. M. (2005). A model of perceived organizational support and Person-organization fit. Honolulu, HI: Presented at the Annual Academy of Management Meeting.

De Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Falcón, J. M. (2002). A resource-based view of human resource management and organizational capabilities development. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13, 123–140.

Deloitte. (2010a). Talent Edge 2020, Blueprints for the new normal. Retrieved from July 21st, 2012, http://www.deloittehumancapital.at/wp-content/6_Talent_WegweiserKrise.Studie.pdf.

Deloitte. (2010b). Trust in the workplace: 2010 ethics & workplace survey. Retrieved from July 20, 2012, http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_US/us/About/Ethics-Independence/index.htm.

Deshpande, S. P., Joseph, J., & Prasad, R. (2006). Factors impacting ethical behavior in hospitals. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 207–216.

Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modelling. Akron, OH: The University of Akron Press.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Standford University Press.

Finegan, J. E. (2000). The impact of Person and organizational values on organizational commitment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 149–169.

Fontrodona, J., & de los Santos, J. (2004). Clima Ético de la Empresa Española: Grado de Implantación de Prácticas Éticas. Working Paper 538, IESE Business School, University of Navarra, Pamplona.

Granitz, N. A. (2003). Individual, social and organizational sources of sharing and variation in the ethical reasoning of managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 42, 101–124.

Guillén, M. (2006) Ética en las organizaciones. Construyendo confianza Madrid: Prentice Hall.

Guillén, M., Melé, D., & Murphy, P. (2002). European vs. American approaches to institutionalisation of business ethics: The Spanish case. Business Ethics: A European Review, 11(2), 167–178.

Gupta, V., Surie, G., Javidan, M., & Chhokar, J. (2002). Southern Asia cluster: Where the old meets the new? Journal of World Business, 37(1), 16–27.

Hartman, E. M. (1998). The role of character in business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(3), 547–559.

Harvey, D. M., Bosco, S. M., & Emanuele, G. (2010). The impact of green-collar workers on organizations. Management Research Review, 33, 499–511.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modelling in international marketing. In R. R. Sinkovics & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing: Advances in international marketing 20 (pp. 277–319). Bingley: Emerald JAI Press.

Herrbach, O., & Mignonac, K. (2007). Is ethical P-O fit really related to individual outcomes?: A study of management-level employees. Business & Society, 46(3), 304–330.

Hodson, R. (2004). Organizational trustworthiness: Findings from the population of organizational ethnographies. Organization Science, 15(4), 432–445.

Hunt, S. D., Wood, V. R., & Chonko, L. B. (1989). Corporate ethical values and organizational commitment. Journal of Marketing, 53(3), 79–90.

Hunter, J. C. (1998). The servant, a simple story about the true essence of Leadership. Roseville, CA: Prima Publishing.

Izraeli, D. (1988). Ethical beliefs and behaviour among managers: A cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(4), 263–271.

James, L. R., Mulaik, S. A., & Brett, J. M. (2006). A tale of two methods. Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 233–244.

Jaramillo, F., Mulki, J. P., & Solomon, P. (2006). The role of ethical climate on salesperson’s role stress, job attitudes, turnover intention, and job performance. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26, 271–282.

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408.

Joiner, T. A., & Bakalis, S. (2006). The antecedents of organizational commitment: The case of Australian casual academics. International Journal of Educational Management, 20, 439–452.

Kaptein, M. (2008). Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: The corporate ethical virtues model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 923–947.

Kenexa Research Institute. (2007). Being socially responsible has a positive impact on employees as well as their local communities and the environment. Executive Summary, No 10. Retrieved from July 21, 2012, http://www.kenexa.com/getattachment/55ec87df-3521-420b-a308-7526d5c5bf60/Being-Socially-Responsible-has-a-Positive-Impact-o.aspx.

Kleinbaum, D. G., Kupper, L. L., & Muller, K. E. (1988). Applied regression analysis and other multivariate analysis methods. Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing Company.

Koh, H. Ch., & Boo, E. H. Y. (2001). The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: A study of managers in Singapore. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(4), 309–324.

Kolodinsky, R. W. (2006). Wisdom, ethics and human resource management: An initial discourse. In F. R. Deckop (Ed.), Human resource management ethics (pp. 47–69). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Konovsky, M. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1991). The perceived fairness of employee drug testing as a predictor of employee attitudes and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(5), 698–707.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. (2001). Bringing leadership lessons from the past into the future. In W. Bennis, G. M. Spreitzer, & T. G. Cummings (Eds.), The future of leadership. Today’s top leaders thinkers speak to tomorrow’s leaders. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1–49.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of Person-job, Person-organization, Person-group, and Person-supervisor Fit’. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

Linz, S. J. (2003). Job satisfaction among Russian workers. International Journal of Manpower, 24(6), 626–645.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Jarvis, C. B. (2005). The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioural and organizational research and some recommended solutions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 710–730.

Martin, K., & Cullen, J. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 175–194.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171–194.

Mayer, D., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13.

Melé, D. (2005). Ethical education in accounting: integrating rules, values and virtues. Journal of Business Ethics, 57, 97–109.

Melé, D. (2009). Business ethics in action, seeking human excellence in organizations. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H., & Axelrod, B. (2001). The war for talent. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Moideenkutty, U., Blau, G., Kumar, R., & Nalakath, A. (2001). Perceived organizational support as a mediator of the relationship of perceived situational factors to affective organizational commitment. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(4), 615–634.

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. (1982). Employee-organizational linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, F., & Locander, W. B. (2006). Effects of ethical climate and supervisory trust on salesperson’s job attitudes and intentions to quit. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26, 19–26.

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, J. F., & Locander, W. B. (2008). Effect of ethical climate on turnover intention: Linking attitudinal and stress theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 559–574.

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, J. F., & Locander, W. B. (2009). Critical role of leadership on ethical climate and salesperson behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 125–141.

Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 157–170.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

O’Fallon, M. J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2005). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics, 59, 375–413.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). Perceived leader integrity and ethical intentions of subordinates. The Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 25, 7–23.

Pettijohn, Ch., Pettijohn, L., & Taylor, A. J. (2008). Salesperson perceptions of ethical behaviours: Their influence on job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 547–557.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, N. P., Shen, W. & Podsakoff, P. M. (2006). The role of formative measurement models in strategic management research: review, critique and implications for future research. In D. Ketchen & D. Bergh (Eds.), Research methodology in strategy and management, Vol. 3 (pp. 201–256). Greenwich: JAI.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Randall, M. L., Cropanzano, R., Boormann, C. A., & Birjulin, A. (1999). Organizational politics and organizational support as predictors of work attitudes, job performance and organizational citizenship behaviours. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 20, 159–174.

Rego, A., Ribeiro, N., & Cunha, M. P. (2010). Perceptions of organizational virtuousness and happiness as predictors of organizational citizenship behaviours. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 215–235.

Rest, J., Narvaez, D., Bebeau, M. J., & Thoma, S. J. (1999). Postconventional moral thinking: A neo-Kohlbergian approach. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sanchis, J. R., & Campos, V. (2008). La innovación social en la empresa: el caso de las cooperativas y de las empresas de economía social en España. Economía Industrial, 368, 187–196.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational Culture and Leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., & Neubaum, D. O. (2005). The effect of leader moral development on ethical climate and employee attitudes. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 97, 135–151.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–453.

Schneider, B., Smith, D. B., Taylor, S., & Fleenor, J. (1998). Personality and organizations: A test of the homogeneity of personality hypothesis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 462–470.

Schwepker, C. H., Jr. (2001). Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention in the salesforce. Journal of Business Research, 54, 39–52.

Seashore, S. E., Lawler III, E. E., Mirvis, P. H., & Cammann, C. (1982). Observing and measuring organizational change: A guide to field practice. New York: Wiley.

Sharma, D., Borna, S., & Stearns, J. M. (2009). An investigation of the effects of corporate ethical values on employee commitment and performance: Examining the moderating role of perceived fairness. Journal of Business Ethics, 89, 251–260.

Sims, R. L., & Keon, T. L. (1997). Ethical work climate as a factor in the development of Person-organization fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1095–1105.

Sims, R. L., & Keon, T. L. (2000). The influence of organizational expectations on ethical decision making conflict. Journal of Business Ethics, 23, 219–228.

Sims, R. L., & Kroeck, K. G. (1994). The influence of ethical fit on employee satisfaction, commitment and turnover. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 939–947.

Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend. Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–231.

Terborg, J. R. (1981). Interactional psychology and research on human behavior in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 6, 569–576.

Thorne, L. (2010). The association between ethical conflict and adverse outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 269–276.

Tippins, M. J., & Sohi, R. S. (2003). IT competency and firm performance: is organizational learning a missing link? Strategic Management Journal, 24(8), 745–761.

Toor, S.-R., & Ofori, G. (2009). Ethical leadership: examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes and organizational culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 533–547.

Treviño, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2004). Managing to be ethical: Debunking five business ethics myths. Academy of Management Executive, 18, 69–81.

Treviño, L. K., Butterfield, K. D., & McCabe, D. L. (1998). The ethical context in organizations: Influences on employee attitudes and behaviours. Business Ethics Quarterly, 8(3), 447–476.

Treviño, L. K., & Nelson, K. A. (2004). Managing business ethics: Straight talk about how to do it right. New York: Wiley.

Treviño, L. K., & Weaver, G. (2001). Organizational justice and ethics program ‘Follow Through’: Influences on employees harmful and helpful behaviour. Business Ethics Quarterly, 11, 651–671.

Valentine, S., & Fleischman, G. (2008). Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 77, 159–172.

Valentine, S., Godkin, L., Fleischman, G. M., & Kidwell, R. (2011). Corporate ethical values, group creativity, job satisfaction and turnover intention: The impact of work context on work response. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 353–372.

Valentine, S., Godkin, L., & Lucero, M. (2002). Ethical context organizational commitment and Person-organization fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 41, 349–360.

Valentine, S., Greller, M. M., & Richtermeyer, S. (2006). Employee job response as a function of ethical context and perceived organization support. Journal of Business Research, 59(5), 582–588.

Valentine, S., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2004). Spanish and American business professionals’ ethical evaluations in global situations. Journal of Business Ethics, 51, 1–14.

Vardi, Y. (2001). The effects of organizational and ethical climates on misconduct at work. Journal of Business Ethics, 29, 325–337.

Verquer, M. L., Beehr, T. A., & Wagner, S. H. (2003). A meta-analysis of relations between Person-organization fit and work attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 473–489.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climate. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 101–125.

Viswesvaran, C., Deshpande, S. P., & Joseph, J. (1998). Job satisfaction as a function of top management support for ethical behavior: A study of Indian managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 365–371.

Vitell, S. J., & Ramos, E. (2006). The impact of corporate ethical values and enforcement of ethical codes on the perceived importance of ethics in business: A comparison of U.S. and Spanish managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 31–43.

War for Talent. (2012). Retrieved from July 31, 2012, http://warfortalentcon.com. San Francisco, CA: Mission Bay Center.

Weaver, G. R., & Treviño, L. K. (2001). The Role of human resources in ethics/compliance management: A fairness perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 11(1), 113–134.

Weeks, W. A., Loe, T. W., Chonko, L. B., & Wakefield, K. (2004). The effect of perceived ethical climate on the search for sales force excellence. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 24, 199–214.

Werts, C. E., Linn, R. L., & Joreskog, K. G. (1974). Interclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 25–33.

Wright, P., McMahan, G., & McWilliams, A. (1994). Human resource and sustained competitive advantage: A resource-based perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 2, 301–326.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruiz-Palomino, P., Martínez-Cañas, R. & Fontrodona, J. Ethical Culture and Employee Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Person-Organization Fit. J Bus Ethics 116, 173–188 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1453-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1453-9