Abstract

Despite efforts to address societal ills, social enterprises face challenges in increasing their impact. Drawing from the RBV, we argue that a social enterprise’s scale of social impact depends on its capabilities to engage stakeholders, attract government support, and generate earned-income. We test our hypotheses on a sample of 171 US-based social enterprises and find support for the hypothesized relationships between these organizational capabilities and scale of social impact. Further, we find that these relationships are contingent upon stewardship culture. Specifically, we show that an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture increases the effects of the capabilities to attract government support and to generate earned-income, while an employee-centered stewardship culture compensates for low abilities to attract government support and to generate earned-income.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social entrepreneurs are often depicted as being driven by an ethical obligation and commitment to help others (Pless 2012; Zahra et al. 2009), which leads them to start social enterprises that are guided by the entrepreneur’s ethical and moral values (Bacq et al. 2016; Kickul and Lyons 2016; Renko 2013). They are motivated by a social vision that compels them to become agents of change through entrepreneurship (Barendsen and Gardner 2004; Dees 1998; Nga and Shamuganathan 2010). Social entrepreneurs take direct actions aimed to make fundamental social changes that are transformative and innovative (Zhang and Swanson 2013). However, like any entrepreneur, social entrepreneurs must create sustainable and viable organizations by acquiring valuable resources and developing capabilities that will maximize their resources’ utility (Meyskens et al. 2010; Renko 2013; Zhang and Swanson 2013). Yet, these social enterprises face significant resource constraints because their primary social mission often drives them to forsake healthier margins in order to reach more beneficiaries (Desa and Basu 2013). Additionally, they often operate in environments that make it difficult to acquire resources at reasonable costs (Zahra et al. 2014). As a result, many social enterprises are not able to solve large-scale problems and the magnitude of their social impact is limited (Renko 2013; Smith et al. 2016; Sud et al. 2009; Zahra et al. 2009).

Some researchers have recognized a bias in the literature that highlights the success of social enterprises rather than identify reasons for any limited impact (Dacin et al. 2010; Renko 2013; Smith et al. 2016). Many social enterprises struggle to achieve organizational sustainability, particularly during difficult economic times (Zhang and Swanson 2013). Further, because social entrepreneurs focus more on value creation than value capture, they often struggle to grow their operations (Santos 2012; Smith et al. 2016). As such, research has called for studies to investigate why some social enterprises are better able to scale their social impact than others (Bloom and Smith 2010; Dees 2008; Meyskens et al. 2010; Renko 2013; Smith et al. 2016). Indeed, scale of social impact, defined as the magnitude of a social need or problem that a social enterprise is able to reach (Dees 2008), is considered one of the most important outcome variables in the social entrepreneurship field (Alvord et al. 2004; Bloom and Smith 2010; Smith et al. 2016). Given that much of the social enterprise literature to date has focused on social entrepreneurs’ motivations (Miller and Wesley 2010; Van de Ven et al. 2007) and opportunity recognition strategies (Alvarez and Barney 2014; Corner and Ho 2010; Di Domenico et al. 2010), and has been based on case studies (Short et al. 2009), we know little about the types of capabilities that social enterprises should build to scale their social impact (Bloom and Chatterji 2009; Meyskens et al. 2010; Zahra et al. 2009).

Despite early calls in the literature to focus on the ‘enterprise’ side of social enterprises to understand how differences in their capabilities lead to differences in their social impact (Litz 1996), few empirical studies have applied a resource-based view (RBV) to explore social enterprises’ scale of social impact. From an RBV perspective, social enterprises are seen as organizations whose scale of social impact is dependent on their ability to build, combine, and apply resources and capabilities. As applied to social entrepreneurship, the RBV offers a framework for understanding how resources and capabilities enhance a firm’s competencies and enable it to serve its target market more effectively (Desa and Basu 2013). This approach is similar to the Radical Alternative to RBV since emphasis is placed on achieving social welfare and well-being for multiple stakeholders (i.e., firm owners, beneficiaries, employees, environment), rather than maximizing the financial welfare of the individual firm, as prescribed by the conventional view of RBV (Bell and Dyck 2011). As such, rather than concentrate on financial performance and win/lose scenarios of gaining a competitive advantage, we take a more Radical approach of RBV (Bell and Dyck 2011) by focusing on a social enterprise’s ability to achieve social impact through capabilities that emphasize cooperation.

Accordingly, we extend the RBV to the study of social entrepreneurship by identifying capabilities that contribute to a social enterprise’s scale of social impact. While rarely applied, the RBV is well suited to study social enterprises as it is concerned with “the combination and management of resources and how these resources flow within an organization to lead to more effective processes” (Meyskens et al. 2010, p. 662). Resources constitute the means through which organizations transform inputs into outputs, and capabilities are the actions through which resources are employed to accomplish the organization’s goals (Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Mathews 2002). The RBV thus portrays an organization as a bundle of resources and capabilities that are developed over time as the organization interacts with stakeholders (Branco and Rodrigues 2006). Given recent research that highlights the importance of social enterprises to effectively attract and communicate with stakeholders (Montgomery et al. 2012; Renko 2013), advocate for government support (Bloom and Smith 2010; Santos 2012; Sud et al. 2009), and develop relationships with paying customers that produce revenue streams (Swanson and Zhang 2010; Zhang and Swanson 2013), we investigate how stakeholder engagement, government support, and earned-income generation influence social enterprises’ scale of social impact.

Additionally, since an endowment of resources and capabilities does not always translate to greater performance, in adopting the RBV it is also necessary to consider how resources and capabilities can be best leveraged (Eddleston et al. 2008). Social enterprises often struggle to accumulate resources and build capabilities, which forces them to maximize the utility of the resources and capabilities that they have available by encouraging employees to cooperate, share knowledge, and take initiative (Zhang and Swanson 2013). We therefore propose that a social enterprise’s organizational culture is key in determining the effectiveness of its capabilities to scale social impact. Building on research that shows that a stewardship culture can serve as an important resource to entrepreneurial firms (Zahra et al. 2008), we propose that stewardship culture is an internal contingency that enhances the deployment of a social enterprise’s capabilities, and can compensate for a lack of capabilities. We define stewardship culture as a culture that nurtures collaboration and citizenship among employees, and promotes a sense of purpose so that the social entrepreneur identifies and emotionally connects with the social mission. While previous research highlights the ‘stewardship’ of social enterprises to the external stakeholders they serve (Mair and Martí 2006; Tan et al. 2005), we contend that a stewardship culture within the organization may distinguish the most successful social enterprises (that is, those with the greatest scale of social impact). Indeed, the Radical approach of the RBV advocates for the development of community and collaboration in organizations as well as opportunities for stewardship in developing a sustainable organization (Bell and Dyck 2011). Drawing from Zahra et al. (2008), we therefore focus on an ‘employee-centered stewardship culture’ that captures the collective interests and citizenship behaviors of a social enterprise’s employees, and an ‘entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture’ that captures the degree to which a social entrepreneur identifies with the social mission and the enterprise is a source of personal satisfaction and self-image.

Therefore, we contribute to the social entrepreneurship literature by extending the RBV to account for the distinct challenges that social enterprises face in building capabilities that will aid their quest for social betterment. Our results demonstrate that the capabilities to engage stakeholders, attract government support, and generate earned-income are positively related to the scale of social impact. Additionally, our study reveals that a stewardship culture can be an important resource for social enterprises that can either compensate for a lack of capabilities or enhance the effectiveness of capabilities in fostering scale of social impact. Our study thereby contributes to the literature by offering a RBV of social enterprises that demonstrates how stewardship can be extended beyond the external social mission of an enterprise to the organization’s internal culture to promote scale of social impact. Finally, our study answers the call for social enterprise research to go beyond case study methodologies to employ systematic empirical analyses that are based on theory-driven arguments (Short et al. 2009; Zahra et al. 2014). In doing so, we show how strategic management theories can be adapted to social entrepreneurship by demonstrating how capabilities that foster cooperation and support can help a social enterprise to better achieve its social mission.

To examine these issues, this manuscript is organized in the following manner. First, we review the literature and present our theoretical model linking organizational capabilities and stewardship culture to the scale of social impact. Second, we detail our methodology to test our hypotheses on a sample of 171 social enterprises based in the United States (US). Third, we discuss the results. Finally, we offer contributions as well as implications of our study for social entrepreneurship theory and practice, and provide several directions for future research.

Literature Review and Theory Development

A Resource-Based View of Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurship involves “the innovative use and combination of resources to pursue opportunities to catalyze social change and/or address social needs” (Mair and Martí 2006, p. 37). It is portrayed as ‘entrepreneurship with a social purpose’ (Austin et al. 2006) that promotes the betterment of humankind and society (Nga and Shamuganathan 2010). Social enterprises differ from traditional commercial enterprises by having social objectives as a central part of their organizational mission (Weerawardena and Mort 2006). Their primary intention is to help others (Pless 2012), and thus social entrepreneurship offers a more ethical variant of entrepreneurial activity (Branzei 2012). Indeed, an emphasis on ‘other-regarding’ over self-interest has a long tradition in ethics research (Jones et al. 2007). Therefore, it is important to business ethics research to understand what factors contribute to social enterprises’ success in having the greatest social impact (Bloom and Smith 2010; Haugh and Talwar 2016; Smith et al. 2016).

As applied to social entrepreneurship, the RBV offers a framework for understanding how resources and capabilities enhance a firm’s competencies and enable it to serve its target beneficiaries more effectively. The Radical approach to the RBV also suggests that a social enterprise’s ability to achieve scale of social impact depends on capabilities that emphasize cooperation. Scale of social impact refers to the magnitude of social value that a social enterprise creates by reaching more people and communities who rely on their solutions for social betterment. It is considered one of the most important dependent variables in social entrepreneurship research (Alvord et al. 2004; Bloom and Smith 2010; Desa and Koch 2014; Smith et al. 2016). However, there is substantial variance in the social value created by social enterprises, with many social enterprises remaining small, geographically limited (Smith et al. 2016) and failing to fully achieve their social mission (Renko 2013).

Although it has been debated how best to define and measure social impact (Ebrahim and Rangan 2014; Renko 2013), with various emphases being placed on types of impact (i.e., economic, psychological, sociological, environmental, etc.), social issues (i.e., health, nutrition, education), and stakeholders (i.e., beneficiaries, volunteers, funders, etc.), a recent review on the subject distinguishes between scope and scale of social impact (Ebrahim and Rangan 2014). Scope refers to the range of interventions required to address a social problem, and scale refers to the geographical reach of the operations—local, regional, national, global. In focusing their theory on the scale of social impact, Smith and colleagues argued that at its core “scaling is an ethical decision because it involved a choice on the part of the social entrepreneur, and that choice has consequences for other people” (2016, p. 682). Similarly, in our study we focus on the scale of social impact. This study adds to recent efforts to build empirical evidence on what drives scale of social impact by extending the RBV to understand why some social enterprises achieve greater impact than others.

Social Enterprise Organizational Capabilities and the Scale of Social Impact

According to the RBV of the firm, a competitive advantage stems from a firm’s resources and competences, and the managerial capability to marshal and apply them (Barney 1991; Grant 1991). Although social enterprises may not be concerned with gaining a competitive advantage over rivals, they do seek to build competencies that will help them serve their target market more effectively (Desa and Basu 2013). Additionally, they often need to compete for stakeholders’ (i.e., donors, volunteers, government, customers) attention and support (Desa and Basu 2013; Zahra et al. 2009). Researchers have started to acknowledge that it is essential for social enterprises to acquire resources and develop capabilities to reach their social goals (Bloom and Chatterji 2009; Meyskens et al. 2010). The capability to acquire, organize, and convert a broad set of tangible resources and intangible processes (for example, skills, abilities, know-how, expertise, designs, management, etc.) should enhance the ability of a social enterprise to create social value (Meyskens et al. 2010). Bloom and Chatterji (2009) proposed seven types of organizational capabilities that social enterprises should seek to develop so as to achieve their social mission. Although some preliminary evidence on the benefits of capabilities to social enterprises exists (Bloom and Smith 2010), more research is needed that empirically examines which capabilities significantly contribute to their scale of social impact and how an organization can capitalize on these capabilities to foster greater social impact.

In this research, we focus on three organizational capabilities that should help a social enterprise to promote social system change and represent potential success factors in the achievement of greater social impact. These capabilities are in line with the Radical RBV in that they consider multiple stakeholders and emphasize the importance of cooperation and support in achieving an enterprise’s social goals. They also reflect theoretical advancements in the field that acknowledge how social change often relies on collaboration and collective action (Haugh and Talwar 2016; Montgomery et al. 2012). When a social enterprise possesses such capabilities, it may have an advantage in terms of scale of social impact. First, characterized by stakeholder multiplicity (Bacq and Lumpkin 2014; Lumpkin et al. 2013), social enterprises need to gain stakeholders’ attention and support. Therefore, we investigate ‘stakeholder engagement’ (also referred to as ‘capability to engage stakeholders’) as the ability to effectively communicate and engage with donors, beneficiaries, customers, and the community. Second, since social enterprises combine aspects of both typical businesses and charities (Battilana et al. 2015), their effectiveness often depends on persuading administrative agencies, legislators, and government leaders to help their cause (Bloom and Smith 2010). We thus study the effect of their ability to garner ‘government support’ on their scale of social impact. Third, given the importance of developing revenue streams that make social enterprises less dependent on donations to remain viable (Gras and Mendoza-Abarca 2014; Mair and Martí 2006; Swanson and Zhang 2010; Zhang and Swanson 2013), we study the effect of ‘earned-income generation’ (or the ‘capability to generate earned-income’) on the scale of social impact.

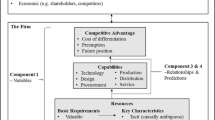

Additionally, the RBV emphasizes that resources and capabilities do not always lead to strong performance; they must be appropriately applied and leveraged to lead to a competitive advantage (Eddleston et al. 2008). Given resource constraints, social enterprises may need to develop capabilities that can compensate for a lack of resources. It has been suggested that the people directly involved in a social enterprise can accomplish great feats when they are motivated by the social mission and make the enterprise’s challenges and opportunities their own (Miller and Wesley 2010; Smith et al. 2016). In particular, the RBV proposes that an organization’s culture can be a key intangible resource that contributes to a firm’s effectiveness (Barney 1986). While there are numerous dimensions of organizational culture (Detert et al. 2000), we focus on stewardship culture since research stresses the importance of cooperation and collectivism (Hart 1995; Montgomery et al. 2012) and the entrepreneur’s identification with the business (Zahra et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2016) to the dedication and pursuit of a social enterprise’s mission. Indeed, research on non-profit organizations emphasizes how a stewardship orientation can increase firm effectiveness by intrinsically motivating employees and encouraging them to feel that the firm’s struggles are their own (Chen et al. 2013; Van Puyvelde et al. 2012). It has also been emphasized that a stewardship culture can be an important resource to entrepreneurial firms that helps them to navigate their environment and overcome challenges (Zahra et al. 2008). Therefore, in this study we extend the RBV to the field of social entrepreneurship by identifying capabilities that could offer social enterprises a distinct benefit in scaling their social impact and by proposing that a stewardship culture can serve as an important resource that leverages the benefits of their capabilities and can compensate for a lack of capabilities. Figure 1 represents our theoretical model.

Stakeholder Engagement According to the RBV, complex social structures that are built over time are often a key resource that contributes to firm success (Barney 1991; Colbert 2004). Because social enterprises seek to produce social change, communicating with a variety of stakeholders can help them to overcome barriers to large-scale social impact (Montgomery et al. 2012; Pearce and Doh 2005). In particular, research has acknowledged how the engagement of stakeholders like donors, customers and the community, can assist social enterprises in acquiring resources and gaining legitimacy (Desa and Basu 2013; Di Domenico et al. 2010; Miller and Wesley 2010). Successful social enterprises appear to be able to capitalize on their social networks to catalyze change and gain support for their mission (Alvord et al. 2004). For example, it has been suggested that those organizations that are best able to communicate their environmental goals to stakeholders have the greatest environmental impact (Hart 1995). Therefore, in applying these arguments to social enterprises, the capability to engage stakeholders should contribute to the scale of social impact.

Indeed, the effectiveness of a social enterprise to persuade external stakeholders to support the value of its social mission through communication and engagement is likely to increase the scale of social impact (Bloom and Chatterji 2009). By informing stakeholders about the value of the social enterprise’s mission and ability to assist beneficiaries, trust and legitimacy is built in the community (Zahra et al. 2014), which thereby increases stakeholder support (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Renko 2013). In addition, stakeholder engagement is important not only to the process of social venture creation by generating new contacts and garnering valuable resources (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Haugh 2007), but also by fostering a solid, loyal network of stakeholders that offer opportunities for the social enterprise to increase its outreach and impact. Without the ability to engage stakeholders, a social enterprise may struggle to inform stakeholders about their mission and to gain their commitment and support, thus limiting its geographical extension (Renko 2013). For instance, some social enterprises fail to achieve a large scale of social impact because they are unable to effectively inform stakeholders about the social ills in the community and how their enterprises can increase social welfare (Zahra et al. 2009). They also tend to experience problems assembling resources, gaining legitimacy (Bloom and Chatterji 2009; Montgomery et al. 2012), and overcoming liabilities of newness and smallness (Desa and Basu 2013). Therefore, social enterprises that are not able to engage various stakeholders often face barriers in achieving large-scale social impact (Montgomery et al. 2012; Sud et al. 2009). Accordingly, we predict that:

Hypothesis 1

The capability to engage stakeholders positively relates to the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Government Support Social enterprises often target gaps in social needs where governments lag, and act as advocates in voicing the needs of a community (London 2008). At their heart, social enterprises engage in social activism which is inherently a political activity that requires exerting pressure on governments to support their mission (Santos 2012). As such, researchers have stressed the need for social enterprises to build political capital by garnering government support (Bloom and Smith 2010; Santos 2012). Research has acknowledged the importance of government support to social enterprises’ effectiveness, with various types of activities such as lobbying, utilizing the courts for social change, and developing political connections, being discussed (e.g., Di Domenico et al. 2010; Bloom and Smith 2010; Santos 2012; Zahra et al. 2014). Here, we refer to the capability to attract government assistance as ‘government support.’

The RBV has long recognized how government support, particularly political capital, can be a key resource to firms, especially as they aim to grow geographically and internationally (Frynas et al. 2006). By gaining government support, the RBV proposes that firms can accrue firm-specific advantages in the market and acquire difficult-to-obtain resources. The RBV thus acknowledges how government intervention can affect firm performance (Boddewyn and Brewer 1994; Frynas et al. 2006). In line with Frynas and colleagues’ depiction of political resources as those firm attributes and capabilities that “allow the firm to use the political process to improve its efficiency and profitability” (2006, p. 324), we define government support as the capability of a social enterprise to acquire government support through supportive legislation and laws, financial assistance, and increased visibility of the social mission within the government’s agenda.

It has been argued that a social enterprise often requires the cooperation of its government in order to increase its social impact (Zahra et al. 2014). Through lobbying and political activity, social enterprises can influence government agendas and persuade officials that their mission is for the benefit of the community (Di Domenico et al. 2010). Lobbying and political activity help a social enterprise communicate a community’s needs and gain support for its mission. In turn, government support helps a social enterprise gain legitimacy (Meyskens et al. 2010), which is believed to contribute to the sustainability of a social enterprise (Zahra et al. 2014). For example, social enterprises that gain government support have benefitted from legal and regulatory changes that contributed to their social impact (Santos 2012). Further, social enterprises appear more likely to expand into new geographic markets and thus increase their number of beneficiaries, when they establish trust-based ties with local governments (Desa and Koch 2014). Government support may also counteract limitations social enterprises face in their resource-constrained environments by helping the social enterprise acquire scarce resources (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Santos 2012).

In contrast, those social enterprises that are unable to garner the support of their government may face limitations that prevent them from fully reaching their goals (Renko 2013; Zahra et al. 2014). These social enterprises may struggle to reach their constituents in need or to gather the resources required for growth. Government regulations can prevent a social enterprise from increasing the scale of its social impact (Weber et al. 2012) and a lack of government support can limit a social enterprise’s ability to reach beneficiaries and to alert society’s members of social ills in the community (Santos 2012). Thus, the capability to attract government support may be a key capability that distinguishes social enterprises with the greatest social impact. Therefore, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2

The capability to attract government support positively relates to the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Earned-Income Generation Despite their efforts to make a positive impact on society, social enterprises often struggle to fund their activities (Doherty et al. 2014; Kickul and Lyons 2015; Zhang and Swanson 2013). They often are not able to attract financial capital through traditional means like commercial loans or issuing stock, which complicates their ability to become financially sustainable (Weerawardena and Mort 2006). As such, because of fundraising difficulties, some social enterprises seek to create revenue streams that would make them less dependent on philanthropy and create some financial slack (Swanson and Zhang 2010; Zhang and Swanson 2013). The RBV recognizes how slack financial resources result in more available resources that can be allocated to achieve an organization’s social mission (Surroca et al. 2010). The capability to earn income allows the profit-generating segment of a social enterprise to fund its non-profit social activities (Boschee 2001). Additionally, the capability of a social enterprise to earn income that exceeds its expenses has been argued to be key in the development of a strong business model (Dart 2004). For example, research suggests that market-based income increases the likelihood that a social enterprise will remain in business (Gras and Mendoza-Abarca 2014). Earned-income may come from beneficiaries directly, in the case of ‘fee-for-service’ operations (Ebrahim et al. 2014) or from better-off customers whose purchase subsidizes the charitable service to beneficiaries. Research on the ‘buy-one give one model’ further suggests that social enterprises that are able to attract paying customers through the sale of products and services are more likely to gain exposure and support for their social cause (Marquis and Park 2014). As such, the social enterprise’s customers often form a collaborative relationship with the enterprise whereby they see their purchase as a way to support and contribute to the social enterprise’s social cause. Thus, in extending the RBV to social entrepreneurship, earned-income generation appears to be an important capability that contributes to scale of social impact.

In contrast, social enterprises that lack earned-income generation may need to limit their social reach particularly when donations and philanthropic gifts are low (Zhang and Swanson 2013). Social enterprises that struggle to achieve financial sustainability through commercial revenues are also likely to struggle in the delivery of their social initiatives (Mair and Martí 2006; Zhang and Swanson 2013). Furthermore, recent research suggests that a lack of earned-income may contribute to mission drift in social enterprises due to accountability issues (Ebrahim et al. 2014; Edwards and Hulme 1996; O’Dwyer and Unerman 2008). That is, in their quest for survival, social enterprises that do not have the ability to generate earned-income are accountable to large donors and financial capital providers whose conditions on the use of funds and reporting requirements can force them to alter their mission, thereby inhibiting their scale of social impact. This risk of mission drift seems particularly likely when a social enterprise is financially dependent on multiple donors and financial capital providers (Ebrahim et al. 2014). The implication for social enterprises is a risk of prioritizing the interests of those powerful donors and financial capital providers over the interests of the beneficiaries that they intend to serve and, as a result, a departure from their original social mission (Minkoff and Powell 2006). Accordingly, research suggests that the ability to generate earned-income helps a social enterprise to achieve its social mission by fostering some financial independence and developing relationships with paying customers (Boschee 2006; Dart 2004; Miller and Wesley 2010). In turn, those social enterprises that are able to earn greater income reduce their reliance on donations and grants, thus increasing their autonomy and ability to focus on scaling social impact (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Swanson and Zhang 2010). Therefore, generating earned-income should be a significant capability that increases scale of social impact.

Hypothesis 3

The capability to generate earned-income positively relates to the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

The Importance of Stewardship Culture as a Resource

An important line of inquiry in the RBV research is exploring the context and contingencies that leverage, or reduce, the effectiveness of resources and capabilities to contribute to firm performance (Eddleston et al. 2008). Although the importance of situational, external contingencies has been underlined in extant research (Bloom and Chatterji 2009), in this study we focus on an important internal contingency that is expected to augment the effects of the three capabilities on the scale of social impact: the organizational culture and, more specifically, a culture that reflects a stewardship philosophy. Since research has shown the importance of organizational culture to ethical values and behaviors in organizations (Neubaum et al. 2004) and stewardship theory recognizes the moral imperative for firm leaders and employees to ‘do the right thing’ (Donaldson and Davis 1991), a stewardship culture seems well suited to leverage the benefits of a social enterprise’s capabilities in increasing its scale of social impact.

An organization’s culture is an important intangible resource that can contribute to a firm’s ability to respond to the environment by enhancing the effectiveness of its capabilities (Eddleston et al. 2008; Zahra et al. 2008). Organizational culture reflects “the enduring values that shape the firms’ characters and how they adapt to the external environment” (Zahra et al. 2004, p. 364). It captures the beliefs, values, and practices that have evolved over time to create heuristics that guide organizational members’ actions (Bargh and Ferguson 2000). Whereas some have alluded to the importance of organizational culture for non-profits to achieve their social mission, this research referred mainly to the entrepreneurial ‘mindset’ or ‘mentality’ in launching the organizations (Boschee 1995). However, recent research on corporate social responsibility has highlighted the importance of organizational culture as an intangible resource that contributes to socially responsible outcomes (Howard-Grenville and Hoffman 2003; Surroca et al. 2010). According to the RBV, an organization’s culture can be a strategic resource that enhances firm performance since it can promote a socially conscious business philosophy that enhances decision-making and collaboration, which in turn enable the most efficient use of an enterprise’s resources and capabilities (Sharma and Vredenburg 1998; Surroca et al. 2010). As such, a social enterprise’s organizational culture may ensure that the enterprise fully leverages its capabilities so as to promote greater social impact.

Although there are numerous dimensions of organizational culture (Detert et al. 2000), we focus on a stewardship orientation since it emphasizes concern for others and collectivism (Davis et al. 1997) and aligns with social entrepreneurship’s focus on ‘other-regarding’ and social improvements. Firm stewardship for the benefit of society has been discussed in relation to spirituality in non-profit firms (Jeavons 1994; McCambridge 2004; Schneider 2013) and to the work and mission of social enterprises (Mair and Martí 2006; Tan et al. 2005). However, although research has praised the stewardship of social enterprises and has stressed the importance of employees’ intrinsic motivation and high commitment to the success of non-profit organizations (Ben-Ner et al. 2011; Van Puyvelde et al. 2012), it is surprising that the social entrepreneurship literature has not embraced stewardship theory to explore the internal dynamics of a social enterprise that could contribute to social impact.

Building on Zahra et al.’s (2008) view of stewardship culture as an important moderator for entrepreneurship scholars to consider, we focus on two dimensions of stewardship culture: one that captures the extent to which the enterprise inspires employee loyalty and collectivism, which we refer to as ‘employee-centered,’ and a second that captures the extent to which the enterprise contributes to an entrepreneur’s self-image and self-actualization, which we refer to as ‘entrepreneur-centered.’ These two dimensions of stewardship culture reflect an organization’s internal values and approach toward employees as well as the personal and psychological motivations of the organization’s leaders (Zahra et al. 2008).

Stewardship theory draws from McGregor’s (1960) classic Theory Y to characterize organizational members as being intrinsically motivated, willing to subordinate personal goals to firm goals, and willing to assume responsibility for the firm’s achievement (Eddleston et al. 2008; Tosi et al. 2003). More specifically, stewardship theory is based on three main assumptions: first, stewardship theorists acknowledge the collectivist and cooperative behaviors of employees; second, stewardship theory views employees as pro-organizational and trustworthy; and third, stewardship theory portrays firm leaders as motivated by a sense of purpose, higher-order needs, and commitment to organizational goals (Sundaramurthy and Lewis 2003). While stewardship theory was first advanced as an alternative to agency theory in explaining principal–agent relationships (Davis et al. 1997), the theory has been extended to the entrepreneurship literature in order to capture entrepreneurs’ relationship with their firm and employees (i.e., Davis et al. 2010; Eddleston and Kellermanns 2007; Miller et al. 2008; Zahra et al. 2008). Rather than focus on the principal–agent or principal–principal relationships, an entrepreneurship perspective of stewardship theory focuses on entrepreneurs’ relationship with their business and employees. Entrepreneurial firms are seen as fostering a stewardship culture when their entrepreneurs place the business’s needs ahead of their own and they create an environment where employees feel cared for and empowered rather than controlled (Davis et al. 2010; Eddleston and Kellermanns 2007; Zahra et al. 2008). Those entrepreneurial firms that lack stewardship are often portrayed as encouraging individualistic behaviors, experiencing difficulties in motivating employees, and gaining their commitment to the firm’s mission. Given our study of young and small social enterprises, we apply the entrepreneurship perspective of stewardship theory to explore how entrepreneurs and employees who reflect stewardship principles can contribute to their social enterprise’s success by augmenting the benefits of their capabilities.

Employee-centered Stewardship Culture A central theme in the entrepreneurship perspective of stewardship theory revolves around the entrepreneur’s view of employees as trustworthy and cooperative versus agency theory’s view of employees as lacking effort and requiring controls to ensure their work performance (Davis et al. 2010; Eddleston et al. 2016). With its emphasis on collaboration, empowerment, and pro-organizational behaviors, stewardship theory highlights how employees can become a key resource to a firm due to their shared sense of responsibility for the firm’s success and willingness to offer discretionary effort (Eddleston et al. 2008). Organizations that develop a strong employee-centered stewardship culture foster rapid knowledge sharing, cooperation, and citizenship behaviors (Zahra et al. 2008). This type of stewardship culture stresses ‘service’ and keeps employees focused on the well-being and success of the small business (Eddleston et al. 2016). An employee-centered stewardship culture espouses the belief that employee initiative is needed to identify and solve firm problems and that collaboration and joint effort produce the best solutions (Zahra et al. 2008). Such a culture where trust and shared responsibility are emphasized is often necessary to ensure that a small business’s capabilities are effectively deployed when opportunities arise. Furthermore, entrepreneurship research that has considered both stewardship theory and the RBV has suggested that an employee-centered stewardship culture is an important resource that helps entrepreneurial firms to carry out their objectives (Eddleston et al. 2008; Zahra et al. 2008).

For example, Aravind, an Indian social enterprise striving to eliminate curable blindness, appears to possess a strong employee-centered stewardship culture. Aravind has built its organizational culture around employee long-term commitment, empowerment, collaboration, and strong spiritual values (Ramahi 2012). Research suggests that an organizational culture that encourages employee commitment, empowerment, and collaboration may be best poised to leverage a firm’s capabilities and, thus, make the greatest impact toward its cause (Hart 1995). Additionally, for those social enterprises with weak capabilities, a strong employee-centered stewardship culture may compensate since it encourages employees to overcome barriers and liabilities.

In comparison, those social enterprises that do not foster a strong employee-centered stewardship culture may stifle employees’ willingness to take initiative, display organizational citizenship behaviors, and identify environmental opportunities. The organization’s culture will not channel employees’ efforts or create a collectivistic culture that could leverage the social enterprise’s capabilities. For example, researchers have suggested that a social enterprise that limits employee participation and empowerment can hurt its scale of social impact by minimizing the intensity with which the enterprise’s ethical and moral intentions inspire employees to pursue firm goals (Smith et al. 2016; Zahra et al. 2009). According to stewardship theory, employees in such organizations are less likely to feel fully committed to their organization’s values and to exert additional effort (Davis et al. 2010). In turn, when an enterprise lacks an employee-centered stewardship culture, the benefits of the social enterprises’ capabilities on the scale of social impact are likely to be hampered. Rather than encourage a culture that supports employee involvement and care, a more control-oriented culture results when an employee-centered stewardship culture is lacking (Zahra et al. 2008). In such an environment, employees are unlikely to gain intrinsic motivation from their work or feel compelled to display citizenship behaviors (Eddleston et al. 2016), thus limiting the benefits of the social enterprise’s capabilities. Therefore, social enterprises with a strong employee-centered stewardship culture may have an advantage in leveraging their capabilities so as to increase their scale of social impact.

More specifically, an employee-centered stewardship culture may augment the positive effect of stakeholder engagement on scale of social impact by mobilizing employees’ efforts to best take advantage of stakeholder support. For instance, social change often requires collective action which can be fostered with an effective organizational culture that creates a sense of community and purpose among stakeholders and organizational members (Montgomery et al. 2012). An employee-centered stewardship culture could also augment the positive effect of government support on scale of social impact by having the employees become advocates for the social enterprise’s mission to ensure that the government is aware of the social issue, that its assistance is fully utilized, and that organizational practices continuously align with government changes. Additionally, the positive influence of earned-income generation on scale of social impact could be enhanced by an employee-centered stewardship culture since employees in such a culture will treat the enterprise’s assets as their own and thus cooperate to maximize the potential of earned-income generating strategies, as well as be cost conscious and prudent, as predicted by stewardship theory. Further, since employees in organizations adopting a stewardship philosophy see the organization’s weaknesses and problems as their own (Davis et al. 1997; Eddleston and Kellermanns 2007; Zahra et al. 2008), an employee-centered stewardship culture will likely help to compensate for a lack of stakeholder engagement, government support, or earned-income generation by motivating employees to work harder on the enterprise’s behalf. Indeed, research has suggested the importance of a stewardship culture in motivating employees of non-profits (Chen et al. 2013) and entrepreneurial organizations (Eddleston et al. 2008; Zahra et al. 2008) to exert extra effort in order to overcome firm struggles, such as a lack of capabilities. Conversely, since employees have discretion in the amount of effort they put forth and the prioritization of work tasks, a lack of employee commitment and cohesion can restrict a firm by generating resistance and extra costs (Branco and Rodrigues 2006). Accordingly, a lack of an employee-centered stewardship culture is likely to hamper the positive effect of capabilities on the scale of social impact.

Hypothesis 4a

Employee-centered stewardship culture positively moderates the relationship between stakeholder engagement and the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Hypothesis 4b

Employee-centered stewardship culture positively moderates the relationship between government support and the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Hypothesis 4c

Employee-centered stewardship culture positively moderates the relationship between earned-income generation and the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Entrepreneur-centered Stewardship Culture Social entrepreneurship research has recently emphasized the central role of a social enterprise’s leadership in achieving the enterprise’s social mission and scaling of social impact (Renko 2013; Smith et al. 2016). At its core, scaling is seen as an ethical decision since it involves a choice on the part of the social entrepreneur that has consequences for others (Smith et al. 2016). Recent research like this acknowledges the important role of the entrepreneur in deciding how to deploy resources and manage capabilities to social impact growth (Desa and Basu 2013; Smith et al. 2016; Zahra et al. 2009). As a result, the firm’s leadership has been depicted as a resource or constraint to the social enterprise (Renko 2013; Smith et al. 2016; Zahra et al. 2009). As a resource, the social entrepreneur capitalizes on the accumulated capabilities of the enterprise to pursue greater scale of social impact. But as a constraint, the social entrepreneur wastes resources and capabilities and allows mission drift.

In applying the RBV to social entrepreneurship, Zhang and Swanson (2013) called for more research considering how social enterprise leaders can capitalize on the resources and capabilities available to them, and develop strategies that will help them reach their social mission. As applied to entrepreneurship research, stewardship theory suggests that entrepreneurs can have different relationships with their firms; while those that espouse stewardship principles strongly identify with the firm and gain a sense of achievement through their firm’s success, others who espouse agency principles see the firm as a means to achieve extrinsic goals (Corbetta and Salvato 2004) and a source of power and control (Smith et al. 2016; Zahra et al. 2009). That is, while stewardship theory acknowledges how intrinsic motivation and identification with the business serve to align an entrepreneur’s goals with that of the business (Zahra et al. 2008), research on social entrepreneurs has also discussed how a desire for control and pursuit of personal agendas have led to a ‘dark side of social entrepreneurship’ that can harm a social enterprise’s effectiveness (Smith et al. 2016; Zahra et al. 2009).

For those organizations that possess a strong entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, organizational goals (i.e., the social mission) are an important source of satisfaction, achievement, and self-image for the entrepreneur (Zahra et al. 2008). An entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture comes to reflect an entrepreneur who is a caretaker of the firm’s assets and gains a sense of purpose, determination, and self-efficacy by establishing and pursuing the firm’s goals and mission. Indeed, entrepreneurship research highlights how a new firm often becomes a reflection of the entrepreneur’s psychological structure and self-image, thus causing him/her to overcome obstacles like resource constraints and to make the most out of scarce resources (Davis et al. 2007; Eddleston 2008; Hollander and Elman 1988). The social entrepreneurship literature also provides evidence on how an entrepreneur’s internal values and intrinsic motivation are necessary in mobilizing resources and capabilities (Desa and Basu 2013; Hemingway 2005).

For instance, some social enterprises have casted their organizational culture on ‘other-regarding’ actions of self-actualizing entrepreneurs. TOMS Shoes, an often-cited example of social enterprise, was created with the mission of ‘helping change lives’ by giving one pair of shoes to a shoeless child in a developing country, for each pair of shoes sold in the developed world. TOMS’s organizational culture reflects the self-actualization and intrinsic motives of its entrepreneur: “Ultimately, I’m trying to create something that’s going to be here long after I’m gone” (emphasis added; Zimmerman 2009). As such, by leaving a personal footprint, this social entrepreneur derives a sense of accomplishment from TOMS’s social achievements.

In social enterprises with a strong entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, the entrepreneur identifies with the enterprise’s goals and mission, which in turn motivates him/her to work harder to complete tasks, overcome barriers, and solve problems. It follows that in such enterprises, the entrepreneur is likely to ensure that the enterprise’s capabilities are fully leveraged so as to scale its social impact. Indeed, social entrepreneurs, as caretakers of the enterprise’s assets, need to make sound choices regarding the allocation of resources and the application of capabilities (McWilliams et al. 2006; Russo and Fouts 1997). Leaders of social enterprises must carefully consider what capabilities are available to them and develop organizational processes that will best apply those capabilities so as to make progress toward their social objectives (Zhang and Swanson 2013). Rather than get caught up in the elegance or novelty of running a social enterprise (Zahra et al. 2009), firm leaders with a stewardship orientation identify with the mission of the organization which leads them to focus their energy on achieving that mission, especially when faced with environmental challenges (Zahra et al. 2008). As such, a strong entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture should promote the most efficient use of an enterprise’s capabilities.

Conversely, those social enterprises that lack an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture may have difficulties staying committed to their enterprise’s original social mission and experience mission drift. Without firm leaders who strongly identify with the enterprise’s mission and gain a sense of accomplishment from its social achievements, these social enterprises may be easily swayed to alter their mission to appease the interests of others such as donors, volunteers, and government agencies, thereby jeopardizing their social impact (Minkoff and Powell 2006). Additionally, the ‘dark side of social entrepreneurship’ suggests that firms with leaders who place their personal interests and needs for power and ego ahead of their business’s social mission can ultimately limit the social enterprise’s scale of social impact (Smith et al. 2016; Zahra et al. 2009). Such entrepreneurs may use the social enterprise’s resources and capabilities for their own benefit and fail to fully apply them for their beneficiaries’ sake.

More specifically, social enterprises with a strong entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture may be best able to mobilize stakeholders’ efforts toward increasing the enterprise’s scale of social impact by providing as a source of inspiration and direction. A culture centered on a legitimate and emblematic spokesperson (Shaw and Carter 2007), who embodies the social mission, should create favorable conditions that leverage the positive effect of an organization’s capability at engaging stakeholders about the value of their support on scale of social impact (Kelly 2001; Van Puyvelde et al. 2012). An entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture should also augment the positive effect of the ability to attract government support on scale of social impact because the entrepreneur, seeing the enterprise’s mission as his/her own, will be willing to make organizational adjustments that will capitalize on government support and also work to maximize the utility of government support in scaling its social impact. Additionally, the benefits of earned-income generation on scale of social impact should be enhanced by an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture since the entrepreneur will act in the best interest of the enterprise and its mission. Indeed, an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture promotes a long-term perspective and the unwavering pursuit of the organization’s mission (Eddleston 2008; Zahra et al. 2008) which should ensure that the social enterprise’s ability to earn income is targeted toward scaling its social impact.

Further, since the entrepreneur adopting a stewardship mindset considers organizational issues and challenges as his/her own (Eddleston 2008), an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture will likely compensate for a lack of stakeholder engagement, government support, and earned-income generation by strengthening the entrepreneur’s commitment to the enterprise’s success (Davis et al. 2007). Indeed, research acknowledges the role of a stewardship mindset in fostering a sense of accomplishment from social achievements (Minkoff and Powell 2006). Such goal alignment should trigger additional efforts from the entrepreneur to overcome organizational deficiencies that limit the enterprise’s scale of social impact.

Conversely, without an organizational culture that embodies an entrepreneur’s sense of achievement and self-image, the social enterprise may fail to fully exploit its capabilities and, thus, limit its scale of social impact. Indeed, research suggests that social entrepreneurs who lack determination, perseverance, and an emotional attachment to their social enterprise have difficulties mobilizing resources and capabilities, and finding avenues for growth (Boschee 1995; Dees 1998). In addition, recent research on the ‘dark side of social entrepreneurship’ (Zahra et al. 2009) suggests that social entrepreneurs’ pursuit of a personal agenda over the enterprise’s social mission and desire for control and power may conflict with scale of social impact (Smith et al. 2016). In line with our RBV of social entrepreneurship, we therefore predict that for those social enterprises that have a low entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, the effects of key organizational capabilities on scale of social impact will be inhibited. Accordingly, we argue that an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture is a strategic resource that magnifies the positive effects of the capabilities to engage stakeholders, attract government support, and generate earned-income on the scale of social impact.

Hypothesis 5a

Entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture positively moderates the relationship between stakeholder engagement and the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Hypothesis 5b

Entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture positively moderates the relationship between government support and the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Hypothesis 5c

Entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture positively moderates the relationship between earned-income generation and the scale of social impact for social enterprises.

Methodology

Data and Sample

Our sample is composed of 171 US-based social enterprises, that is, organizations that primarily aim to achieve a social mission through business practices (Dacin et al. 2010; Dees 1998). The social enterprises came from nine different fields of work: civic engagement (14 %), economic development (16 %), environment (13 %), health (4 %), human rights (2 %), education (21 %), support services to social enterprises (22 %), retail (6 %), and housing (2 %). 39 percent of these enterprises were for-profit, while the remaining were organized as non-profits, as indicated in Table 1 which presents other descriptive statistics of our sample.

Social enterprises were identified through their entrepreneur’s past participation in a social entrepreneurship program at a major university located in the Northeast of the US. Participants had previously agreed to be contacted. Data were collected from participants via an online survey (21 % response rate). This method of data collection is consistent with our research objective and aims to help address the gap of quantitative, hypothesis-testing studies in social entrepreneurship research claimed by Short et al. (2009). We followed the recommendations of Dillman (2007) for effective questionnaire design and survey implementation, as well as design procedures idiosyncratic to Internet-based surveys.

In order to evaluate the quality of our questionnaire, we conducted two pre-tests. First, we pre-tested the questionnaire with expert scholars in the field to guarantee that our questionnaire made sense based on their knowledge and the extant social entrepreneurship literature. Second, we pre-tested the electronic survey with a dozen social entrepreneurs. Based upon feedback obtained from this pilot group, we refined the phrasing of some questions and added clarifying statements.

Although the sample size of our study and the generalizability of our findings may be a concern, a power analysis, conducted in G*Power (Faul et al. 2009), suggests that the power levels are highly acceptable (Cohen 1988). Following Cohen’s (1988) power analysis procedure, the recommended sample size for our model is 155 for a 90 % level of power (α = .01; medium f 2 = .15). Our sample size of 171 is above this recommendation. A post hoc analysis based on a sample size of 171 further indicates a power of 93.6 %. Accordingly, we do not think that our findings were adversely affected by sample size considerations.

Non-Response Bias

In order to assess potential non-response bias, we tested for differences between early and late respondents. Indeed, prior research indicates that late respondents are more similar to non-respondents (Kanuk and Berenson 1975; Oppenheim 1966). Since we do not have access to data from non-respondents, we followed the strategy proposed by Eddleston et al. (2008) to test for non-response bias. We split our data based on when the questionnaires were received and then conducted analyses of the variance (ANOVA) between early and late respondents. We did not discover any statistically significant differences between the two groups; therefore, non-response bias does not appear to pose a problem to our study.

Assessment of Common Method Bias

Although using key informants and self-reported data is frequent in management and entrepreneurship research, it exposes the data to the risk of common method bias (Krishnan et al. 2006). Therefore, to prevent the occurrence of such a bias, we placed the measures of the predictor and criterion variables far apart in the questionnaire, as recommended by Krishnan et al. (2006). We also guaranteed for response confidentiality (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

Further, in order to evaluate the presence of common method bias, we conducted two post hoc tests. First, following Podsakoff et al. (2003) recommendation, we conducted a Harman’s one-factor test. We tested an unrotated exploratory factor analysis on the items of the independent and moderator variables (we did not include the control variables in this test because one of them is dichotomous, and the other ones are objective measures). When the risk of common method bias is high, the test shows that a single factor can be extracted to explain the majority of the variance of the data. Using SPSS, we extracted five factors with eigenvalues superior to 1.0, which accounted for 70 % of the variance. Of these factors, the first factor accounted for no more than 32 % of the variance. We concluded that common method bias was not a problem in the current study since no single factor accounted for the majority of the variance and the individual factors separated cleanly.

Although necessary, the Harman’s one-factor test presents some limitations (Chang et al. 2010). Therefore, we performed additional post hoc analyses to test for common method variance. We used the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion based on the idea that a variable should share more variance with its assigned indicators than with any other variables. As indicated on the diagonal in Table 1, this criterion is verified as the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each variable is considerably greater than the corresponding inter-construct Pearson zero-order correlations.

Measures

All constructs were measured using 5-point Likert-type empirically validated scales. To assess their internal reliability and convergent validity, in line with Flatten et al. (2015), we calculated Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and AVE. The threshold for Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability is .60 (DeVellis 2003, cited in Flatten et al. 2015). In order to guarantee convergent validity, AVE should be superior to .50, indicating that the construct explains more than half of the variance (Götz et al. 2009). As indicated below, satisfactory reliability and convergent validity are achieved for our constructs.

Stakeholder Engagement In order to measure the capability of the social enterprise to engage stakeholders, we used a five-point Likert-type scale developed by Bloom and Smith (2010). The three items were as follows: “We have been effective at communicating what we do to key constituencies and stakeholders,” “We have been successful at informing the individuals we seek to serve about the value of our program for them,” and “We have been successful at informing donors and funders about the value of what we do.” The items were preceded by the following directions: “Thinking about the last three years of operations of your organization, please indicate how strongly you agree or disagree with each of the following statements.” Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) with the statements prompted by: “Compared to other organizations working to resolve similar social problems as our organization…” The scales we used to measure government support, earned-income generation, and scale of social impact included the same directions and were preceded by the same statement that asked respondents to compare their social enterprise to others working to address similar problems. Those scales were validated on a large-scale sample of 591 social enterprises in the US. The alpha for the stakeholder engagement scale was .68, the composite reliability was .81, and the AVE was .61.

Government Support We measured the capability of the social enterprise to attract government support using three items developed by Bloom and Smith (2010): “We have been successful at getting government agencies and officials to provide financial support for our efforts,” “We have been successful at getting government agencies and officials to create laws, rules, and regulations that support our efforts,” and “We have been able to raise our cause to a higher place on the public agenda.” An alpha of .69 was observed, the composite reliability was .83, and the AVE was .61.

Earned-Income Generation To assess the capability of the social enterprise to generate earned-income, we utilized two items suggested by Bloom and Smith (2010): “We have generated a strong stream of revenues from products and services that we sell for a price” and “We have found ways to finance our activities that keep us sustainable.” We observed an alpha of .60, a composite reliability of .83, and an AVE of .71.

Stewardship Culture In assessing stewardship culture, we used two scales proposed by Zahra and colleagues (2008), ranging from 1 “not at all” to 5 “to an extreme extent.” In order to measure employee-centered stewardship culture, we used four items: “To what extent does your business allow employees to reach their full potential?” “To what extent does your business foster a professionally oriented workplace?” “To what extent does your business inspire employees’ care, and loyalty?” and “To what extent does your business encourage a collectivist rather than an individualistic culture?” To capture entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, we used the five-item scale intended to measure the extent to which an organization’s leader “values positive, intrinsic motivations consistent with stewardship-oriented behaviors” (Zahra et al. 2008, p. 1043). The items included: “To what extent does your business satisfy your need for achievement?” “To what extent does your business satisfy your personal needs?” “To what extent does your business satisfy your opportunities for growth?” “To what extent does your business contribute to your self-image?” and “To what extent does your business make you feel self-actualized?” The alphas for these scales were .81 and .89, respectively, further validating Zahra and colleagues’ (2008) findings. The composite reliabilities of the stewardship scales both exceeded .90, and the AVE was .64 and .67, respectively.

Scale of Social Impact We captured scale of social impact by building on Bloom and Smith’s (2010) method of asking social entrepreneurs to rate their organizations’ social achievements, “compared to other organizations working to resolve similar social problems as their organization.” Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed with the following four statements: “We have made significant progress in alleviating the problem,” “We have scaled up our capabilities to address the problem,” “We have greatly expanded the number of individuals we serve,” and “We have substantially increased the geographic area we serve.” The alpha for this scale was .78, the composite reliability was .86, and the AVE was .61.

Measures of Control Variables

We included three control variables believed to have an influence on the scale of social impact. The age of a social enterprise (number of years of activity) was included since it may affect its scale of social impact. Indeed, a young social enterprise, compared to an older one, might underperform in terms of scale of social impact due to a lack of experience (Renko 2013). Second, we controlled for the effect of firm size (number of full-time employees) on the scale of social impact. Third, the organizational form of a social enterprise (0 = non-profit; 1 = for-profit) may also have an effect on the scale of social impact.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations are shown in Table 1.

The hypotheses proposed in our theoretical model were tested using multiple regression analysis. Results are presented in Table 2. In Model 1, the control variables were entered and two of the three are significantly related to the scale of social impact. That is, the number of full-time employees is positively related to the scale of social impact, while being organized as a for-profit is negatively related with scale of social impact. In order to test Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3, we entered the independent variables in the second model. As indicated in Model 2, a significant change in R 2 was observed (ΔR 2 = .16, p < .001). Stakeholder engagement (b = .21, p < .01), government support (b = .19, p < .05), and earned-income generation (b = .20, p < .01) were all found to be positively related to the scale of social impact. Therefore, we found support for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3.

In order to test the hypothesized moderation effects, we first entered the two moderators independently in Model 3 (ΔR 2 = .02, p < .05) and then entered the six interaction terms in Model 4 (as well as the interaction term between the two moderators). In Model 4, a significant change in R 2 was observed (ΔR 2 = .07, p < .05). The set of Hypotheses 4 proposed that the relationships between the different types of organizational capabilities and the scale of social impact would be moderated by an employee-centered stewardship culture. As Model 4 demonstrates, a significant interaction was found between an employee-centered stewardship culture and government support (H4b: b = −.19, p < .05) and earned-income generation (H4c: b = −.43, p < .001). We discuss these results below. Hypothesis 4a, which hypothesized that employee-centered stewardship culture would moderate the relationship between stakeholder engagement and scale of social impact, was not supported (H4a: b = .16, n.s.).

For the set of Hypotheses 5, we argued that an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture would moderate the relationships between stakeholder engagement, government support, earned-income generation, and the scale of social impact. A significant interaction was observed between an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture and government support (H5b: b = .21, p < .05). Hypothesis H5c, which proposed that an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture would moderate the relationship between the capability to generate earned-income and scale of social impact, was also supported (H5c: b = .29, p < .05). However, the interaction effect between an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture and stakeholder engagement was not significant (H5a: b = −.16, n.s.).

To facilitate the interpretation of the moderation effects, the significant interactions are plotted in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5. The interaction between employee-centered stewardship culture and government support in Fig. 2 shows that in social enterprises with a low level of employee-centered stewardship culture, a high capability to attract government support is necessary to see a strong scale of social impact. However, when the employee-centered stewardship culture is high, the ability to attract government support is not critical to the scale of social impact. It appears that a high employee-centered stewardship culture can compensate for a lack of government support, as we suggested. Yet, the figure also shows that a high employee-centered stewardship culture does not enhance the benefits of strong government support. Therefore, Hypothesis 4b was not fully supported.

A similar moderation effect was found between employee-centered stewardship culture and earned-income generation, as portrayed in Fig. 3. In social enterprises with low employee-centered stewardship culture, a high capability to generate earned-income is necessary to ensure a strong scale of social impact. However, as predicted, when employee-centered stewardship culture is high, the ability to generate earned-income is not necessary to produce a strong scale of social impact. These results suggest that a high employee-centered stewardship culture can compensate for a lack of earned-income generation. Additionally, the figure indicates that contrary to our hypothesis, a high employee-centered stewardship culture does not enhance the benefits of strong earned-income generation. Therefore, Hypothesis 4c was not fully supported.

Turning to the interaction effects of entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, our findings were as anticipated. As shown in Fig. 4, we found that a high level of entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture augments the benefits of a strong capability to attract government support on the scale of social impact. In contrast, for social enterprises with a low level of entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, a high level of government support does not enhance the scale of social impact. Therefore, Hypothesis 5b is supported.

The fourth interaction effect between entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture and earned-income generation is displayed in Fig. 5. The interaction shows that in social enterprises with a high level of entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, the capability to generate earned-income has a significant positive effect on the scale of social impact. As such, a high entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture enhances the benefits accrued from strong earned-income generation on the scale of social impact. For those enterprises with a low entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture, the capability of high earned-income generation to foster a greater scale of social impact is hampered. These findings support Hypothesis 5c.

Post hoc Tests

In addition, we ran some post hoc analyses (Model 5 in Table 2) to test for any three-way interaction effects between the two types of stewardship culture, and each of our three organizational capabilities. We observed a significant change in R 2 (ΔR 2 = .04, p < .05) and found two significant effects. First, we found a negative, significant interaction effect between the two types of stewardship culture and stakeholder engagement on the scale of social impact (b = −.41, p < .05). Second, we found a positive interaction effect between the two moderating variables and earned-income generation on the scale of social impact (b = .54, p < .01). These effects are represented in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively.

Regarding a high capability to engage stakeholders, the three-way interaction shows that a high employee-centered stewardship culture paired with a high entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture enhances the benefits of stakeholder engagement on the scale of social impact. However, the highest scale of social impact was for those enterprises with high stakeholder engagement and high employee-centered stewardship culture but low entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture. When stakeholder engagement was low, these enterprises also reported the weakest scale of social impact. Thus, it is interesting to observe that while the scale of social impact increases with higher capability to engage stakeholders for all configurations, it increases at a much faster rate for those with a high employee-centered, but low entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture.

In terms of the capability to generate earned-income, the nature of the interaction suggests that while social enterprises with high employee-centered but low entrepreneur-centered stewardship cultures can significantly compensate for an inability to generate earned-income, when enterprises have a higher capability to generate earned-income, their scale of social impact is low. Social enterprises with high employee-centered stewardship culture and high entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture appear best able to capitalize on strong earned-income generation to increase their scale of social impact.

Discussion

Despite efforts to address societal ills, social enterprises face constant challenges to increase their social impact. Although critical resource constraints can limit their margins and hamper their effectiveness, few studies have explored what drives, or restricts, their scale of social impact (Bloom and Smith 2010; Smith et al. 2016). Our study helps fill this gap in the literature by extending the RBV to demonstrate that the capabilities to engage stakeholders, attract government support, and generate earned-income positively relate to the scale of social impact. As such, we show how capabilities that foster cooperation and support can help a social enterprise to better achieve its social mission. First, a social enterprise’s ability to engage stakeholders in the social mission is key to fostering the greatest social impact. Second, another distinctive capability of social enterprises consists of attracting government and political support for a cause, which we found to be positively associated with the scale of social impact. Third, our findings reinforce the importance for social enterprises to be able to generate revenues in the prospect of becoming self-reliant in order to grow their social impact.

Additionally, our study extends the RBV by demonstrating that social enterprises with a stewardship culture can either compensate for a lack of capabilities or enhance the effectiveness of their capabilities in fostering scale of social impact. More specifically, while a high employee-centered stewardship culture was found to compensate for a low ability to attract government support and to generate earned-income, a high entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture was found to augment the positive effects of the ability to gain government support and to generate earned-income on the scale of social impact. These new insights indicate that social enterprises lacking the capabilities to attract government support and/or generate sufficient earned-income should focus on nurturing a collective organizational culture that fosters collaboration and citizenship behaviors among employees. Such a compensating effect of an employee-centered stewardship culture should be further investigated in future research. Additionally, our study demonstrates that those social enterprises with an entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture appear best able to capitalize on government support and earned-income generation to scale social impact. Future research should explore the important role of a social enterprise’s leadership in establishing and reaching its social goals.

Furthermore, although our results support the hypothesized positive relationships between the organizational capabilities to engage stakeholders and generate earned-income, and the scale of social impact, our post hoc analyses revealed that these relationships are contingent upon the level and type of stewardship cultures that the social enterprise has nurtured. In both cases, a high employee-centered stewardship culture paired with a high entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture was found to be particularly effective at leveraging the benefits of a strong capability to engage stakeholders and to generate earned-income on the scale of social impact. Additionally, when the ability to engage stakeholders was low, the compensating effect of a high employee-centered stewardship culture was particularly pronounced when combined with a high entrepreneur-centered stewardship culture.