Abstract

The United States is one of the most charitable nations, yet comprises some of the most materialistic citizens in the world. Interestingly, little is known about how the consumer trait of materialism, as well as the opposing moral trait of gratitude, influences charitable giving. We address this gap in the literature by theorizing and empirically testing that the effects of these consumer traits on charitable behavior can be explained by diverse motivations. We discuss the theoretical implications, along with implications for charitable organizations, and offer suggestions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Charitable giving in the United States has been trending upward in recent years and was estimated at $335.17 billion in 2013 (Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy 2014). According to statistics published by the National Philanthropic Trust, 94.5 % of households gave an average of $2974 to charity in 2013, and 64.5 million adults volunteered 7.9 billion hours of service worth an estimated $175 billion (http://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/). These statistics are indicative of the extraordinary generosity of American citizens and raise a question as to what motivates individuals to contribute time and money to charitable organizations. Substantiating this issue is the call for research to examine the influence of consumer personality traits on donations, enabling nonprofits to better understand their donors and enhance their revenues (O’Reilly et al. 2012).

While the United States is the most charitable nation in the world (Charities Aid Foundation 2014), its citizens are also often considered to be some of the most materialistic (Ger and Belk 1990). Extant research reveals mixed findings regarding the relationship between consumer materialism and ethical or charitable behavior (Arli and Tjiptono 2014; Lu and Lu 2010). For instance, some studies link materialism to unethical consumer behavior (Muncy and Eastman 1998; Chowdhury and Fernando 2013), and find a negative association between materialism and charitable contributions (O’Reilly et al. 2012; Richins and Dawson 1992). Another study shows materialism maintains both a negative and positive association with charitable behavior (Mathur 2013). Specifically, Mathur (2013) finds materialism negatively affects charitable behavior through inverse associations with empathy and social responsibility; yet, he also finds a direct positive relationship between materialism and charitable behavior. These results suggest that it is possible for the apparently contradictory values of materialism and generosity to exist at the same time in the same individual, and more importantly, that the positive impact of materialism on charitable giving cannot be explained by the mediating constructs of empathy and social responsibility. In accordance with Zhao et al. (2010), these initial results suggest an incomplete framework and the likelihood of a missing mediator within the direct path. In this article, we propose that motivations may be the missing link between materialism and charitable behavior.

The literature suggests that there are many different aspects of what motivates consumers’ charitable behaviors (Osili et al. 2011; Van Leeuwen and Wiepking 2013). Social exchange theory (Homans 1958; Emerson 1976) suggests that “we give in order to receive” (Pitt et al. 2001, p. 51). However, what one is looking to receive may vary greatly. First is the idea of feeling good about helping others (Prendergast and Maggie 2013), that is, the joy experienced by giving to worthy causes (Van Leeuwen and Wiepking 2013). Second is giving to others to feel better about oneself (Clary et al. 1998) or because the donor reaps benefits in terms of status, reputation, and/or incentives (Clary et al. 1998; Van Leeuwen and Wiepking 2013). Another aspect discussed frequently in the literature is the social benefits of giving (Clary et al. 1998; Prendergast and Maggie 2013). While there have been many articles that address the relationship between demographics and charitable behaviors (Schlegelmilch et al. 1997), this research makes a contribution by looking beyond demographics to examine the impact of consumer traits, specifically materialism and its inversely associated trait—gratitude (Lambert et al. 2009; McCullough et al. 2002) and motivations on charitable behaviors. In examining these relationships, we answer Mathur’s (2013) call to further assess how materialism positively influences charitable behaviors. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of consumers’ charitable motivations on donations of both time and money (generosity), and to determine how these motivations account for the relationships between consumer traits and charitable behaviors. In addition to addressing an important gap in the literature, this research assists nonprofits in encouraging increased charitable behaviors by providing a better understanding of the characteristics and motivations of donors.

This paper will first discuss the literature on the motivations for consumer charitable behaviors (e.g., donation and volunteering). Next, we will describe the materialism and gratitude literature, and develop hypotheses regarding how specific charitable motivations account for the relationships between these consumer traits and charitable behavior intentions. We then present our methodology and results, followed by a discussion of the theoretical and managerial implications for nonprofit organizations.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Motivations for Charitable Behavior

Many possible motivations for charitable behavior exist, and they can be generally categorized as either self-sacrificing or self-serving. The appeals marketers use to gain support for charities exemplifies this categorization, as marketers commonly position “charitable giving either egoistically (i.e., by highlighting the benefits for the donor) or altruistically (i.e., by the highlighting the benefits for others)” (White and Peloza (2009, p. 109). While a self-sacrificing or altruistic motivation would characterize the agapic model of pure and selfless giving (Belk and Coon 1993), the self-serving or more egoistically model would be more characteristic of the social exchange model (Homans 1958; Gouldner 1960; Emerson 1976) due to the idea of wanting to get something in return for one’s charitable behavior. Pitt et al. (2001) describe that donations motivated by reciprocity would follow a social exchange model even if what is being received is only symbolic in nature, while those who donate without any intentions of reciprocity would characterize the agapic model. The self-sacrificing motivation for charitable behavior is embodied in the “values” function identified by Clary et al. (1998), in which volunteerism is a means for individuals to “express values related to altruistic and humanitarian concern for others” (Clary et al. 1998, p. 1517). The psychological benefits for the donor (“warm glow”) that can result from charitable action (Harbaugh 1998; Khalil 2004) might be viewed as a selfish reason for giving, but can also be considered inherent to altruistic behavior.

While charitable behavior involves self-sacrifice and may be inspired by altruism, it may also be motivated by factors that are more self-serving or egoistical (White and Peloza 2009). Social exchange theory suggests that even with charitable behavior, donors may be looking for some reward or benefit in response to their donations (Mathur 1996; Pitt et al. 2001). In addition to the more selfless “values” function, Clary et al. (1998) suggested that volunteering can also provide individuals with opportunities to (1) learn or use knowledge and skills that might otherwise go unlearned or unused (the “understanding” function); (2) socialize with friends and participate in activities viewed favorably by them (the “social” function); (3) prepare for a new career and/or maintain skills relevant to a career (the “career” function); (4) address their own personal problems and their feelings of guilt over being more fortunate than others (the “protective” function); and (5) achieve personal growth and build self-esteem (the “enhancement” function). Khalil (2004) discusses “rationalistic” theories of altruism, which explain charitable giving as a means of optimizing a donor’s future benefits or personal utility, and concludes that many people who say that their donations are motivated by a desire to help others really have more self-serving motives.

Another possible self-serving motive for charitable giving is a desire for recognition or status on the part of the donor. Bazilian (2012) argues that giving is the newest status symbol among wealthy individuals and corporations. Harbaugh (1998) identifies “prestige benefits” as a possible motive for charitable giving, where such benefits result from others knowing if and how much a donor has given. Munoz-Garcia (2011) suggests that donors actually compete with each other for status, where status increases with the difference between the donation amounts. The desire for status by donors has led charities to report donations and/or use sequential fundraising campaigns (in which charities announce large donations from wealthy and well-respected donors before soliciting other donations) because total donations increase as others try to associate themselves with the high-status “lead” donors (Kumru and Vesterlund 2010; Munoz-Garcia 2011).

Materialism

Materialism has been described in the literature as the importance a consumer attaches to possessions, with the idea that possessions play a central role in one’s life (Belk 1984, 1985; Cleveland et al. 2011; Ger and Belk 1990). Flynn et al. (2013, p. 49) describe materialism as “overestimating the importance of material goods to human happiness.” A consistency in defining materialism is the idea that consumers are looking for more than just utility or instrumental value, and seek to define themselves (Shrum et al. 2013) and enhance their well-being through the consumption process (Kilbourne and Pickett 2008). For marketers, materialism is a critical individual difference variable to segment markets (Cleveland et al. 2009; Griffin et al. 2004). In this paper, we suggest that materialism, as a means to define oneself, may be useful as a segmentation variable to better target potential donors for a nonprofit organization, particularly those drawn by more egoistical than altruistic motivations.

Materialism has been studied both as a personality trait (Belk 1984, 1985) and as a value (Richins and Dawson 1992; Richins 1994). Both involve seeking happiness through consumption (Flynn et al. 2013), but materialistic values have a highly other-directed and public orientation, linking consumption to a desire to display success (Podoshen and Andrzejewski 2012) and arouse envy (Wong 1997, p. 201). Clark and Micken (2002) found that highly materialistic consumers placed greater importance on the external values of belonging and being well-respected than less-materialistic consumers.

Materialism has often been perceived in a negative light as greedy, conspicuous consumption (Josuh et al. 2001). Materialistic consumers place more importance on acquiring possessions merely for display rather than for their functional utility (Belk 1985; Richins and Dawson 1992; Weidmann et al. 2009; Wong 1997). The literature suggests that materialistic people are more likely to value products that signal accomplishment and enhance social status and owners’ appearances (Richins and Dawson 1992; Richins 1994). Hudders (2012) found that external motives to purchase luxury brands are more important for highly materialistic consumers than for low-materialistic consumers. Likewise, Richins (1994) found that consumers with higher levels of materialism place greater value on possessions that are publicly consumed, more expensive, and more likely to relate to the financial worth of the possession. Thus, the literature has clearly demonstrated a link between materialism, social needs (including status), and consumption behaviors. However, research remains to link the notion of materialism and looking good socially with doing good things socially.

While materialism has often been viewed in a negative light, there may also be a positive aspect of materialism in that consumption may aid with identity, enhance well-being (Ger and Belk 1996, 1999; Karabati and Cemalcilar 2010; Kilbourne et al. 2005; Shrum et al. 2013), and reduce uncertainty in one’s life (Chang and Arkin 2002; Micken and Roberts 1999). Shrum et al. (2013, p. 1180) propose “materialism is the extent to which individuals engage in the construction and maintenance of the self through the acquisition and use of products, services, experiences, or relationships that are perceived to provide desirable symbolic value.” Their definition focuses on the motives for materialistic behavior, with the key function of materialism being the construction/maintenance of the self (Shrum et al. 2013). They build on six distinct identity motives from the literature (self-esteem, continuity, distinctiveness, belonging, efficacy, and meaning) and link these motives to materialism and consumption to address why people consume this way (Shrum et al. 2013). The process of self-identity occurs by the symbolic function of acquisitions through signaling, and this signaling can either be a self-signal or other-signal (Shrum et al. 2013). Thus, whether materialism helps or hinders well-being may depend on the motives for the materialistic behavior and if those motives are fulfilled through self- or other-signaling; for example, when the goal is to maintain an identity through other-signaling, the impact may be negative (Shrum et al. 2013).

Micken and Roberts (1999, p. 513) suggest “that materialists are not motivated by the pursuit of possessions, but rather by a desire for certainty” and people utilize possessions to construct and assess their own and others’ identities. In other words, it is not the possessions themselves that provide happiness, but the decrease in uncertainty (Micken and Roberts 1999). In agreement with this notion, Chang and Arkin (2002) suggest people turn to materialism when they experience uncertainty, either within the self (self-doubt) or within society (anomie), and this uncertainty predicts materialism in terms of the success and happiness dimensions as ownership of possessions may aid in providing norms and guidelines for success and aspirations. Additional empirical evidence further validates the link between materialism and uncertainty, as Christopher et al. (2006) find personal insecurity as an antecedent of materialism. Taken together, these articles suggest that possessions may help consumers cope with uncertainty.

These dual aspects of materialism have been viewed as instrumental versus terminal materialism. “Terminal materialism represents a high level of preoccupation with the acquisition and ownership of material objects simply for the sake of possessing them” while instrumental materialism, which may even be necessary, connotes the use of things “merely as a means to achieve some higher end(s)” (Burroughs and Rindfleisch 1997, p. 89). While instrumental materialism is seen as essential to discovering and meeting ones’ goals and basic needs, terminal materialism involves the use of possessions to generate envy or achieve status—the idea of “materialism for the sake of materialism” (Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton 1978, 1981; Richins and Dawson 1992; Sirgy et al. 1998, p. 125). Unanue et al. (2014, p. 581) offer that the quest for material goods takes “time and energy away from fulfilling basic psychological needs” and that “the higher the materialistic value orientation, the higher the need frustration and, in turn, the lower the well-being and the higher the ill-being.” Consequently, it is advocated that while terminal materialism is harmful, instrumental materialism (in which materialistic purchases serve as tools for empowerment, control, independence, and security, and other nonmaterial sources of happiness) is not harmful (Ger and Belk 1999). Nonetheless, the literature acknowledges the difficulties in delineating these two aspects of materialism (Richins and Dawson 1992) and recent research has delved deeper into their association, suggesting that “materialism (instrumental value) motivates the attainment of three major life goals or terminal values: happiness, social recognition, and uniqueness” (Gurel-Atay et al. 2014, p. 502).

Relationship Between Materialism and Charitable Behaviors

Muncy and Eastman (1998) suggest that with higher levels of materialism, concern for others and spirituality may become secondary to a primary focus on acquiring possessions. Extant research further explores the relationship between materialism and ethical behavior by incorporating a consumer’s ethical philosophy, revealing that materialists with a relativistic moral philosophy are more likely to engage in questionable, but legal, consumer behaviors (Lu and Lu 2010).

As noted earlier though Mathur (2013) examined the relationship between materialism and generosity and found that there can be a positive relationship between these two apparently conflicting values. This suggests that the two values can co-exist in the same person at the same time, but may alternate as the dominant value over time. There was no support for the propositions that there are two separate segments of the population (one primarily materialistic and the other primarily altruistic), or that these conflicting values reflected the country’s state of economic development (i.e., that more advanced countries can focus more on higher-order, less-materialistic needs) (Mathur 2013). Mathur (2013) noted, however, that the positive relationship between materialism and charitable giving could be attributed to either common antecedents (e.g., a desire for status) or to the possibility that the motivations for materialistic behavior and charitable behavior coincide. We suggest a materialistic person may be generous due to egoistic type motivations rather than agapic, self-sacrifice, or more altruistic motivations.

Social exchange theory provides a theoretical foundation for why materialism and charitable giving can coincide. Specifically, social exchange theory would suggest that materialistic people donate to receive some gratification, pleasure, satisfaction (Thibaut and Kelley 1959), or some form of social power (Homans 1958; Emerson 1976), which is consistent with the argument that “charitable contributions may be motivated by givers’ self-interest” (Mathur 1996, p. 108; Pitt and Skelly 1984). In examining charitable giving for older adults, Mathur (1996) proposes individuals would engage in charitable activities when the outcome or benefit of that activity is at least equal to the cost of the activity. This proposition, that donors want to maximize the rewards they receive from giving, with rewards exceeding costs, corresponds to one of the key tenets of social exchange theory (Blau 1964). Thus, in accordance with social exchange theory, egotistical motivations may explain why materialism and charitable giving co-exist.

In examining the six motivations for charitable behaviors suggested by Clary et al. (1998), we suggest that the protective and enhancement motives are most relevant to materialism, as these two motives are more egotistically oriented than the remaining motivations. To clarify, the protective function implies that individuals perform charitable behaviors to address their personal problems, to escape from negative self-feelings or perceptions, or to reduce feelings of guilt about having more than others, while the enhancement function refers to achieving personal growth (Clary et al. 1998). These motives are similar in that both focus on inner self-views often perceived by materialistic consumers (Clary et al. 1998; Park and John 2010). However, a critical difference is that the protection function focuses on eliminating negative self-views or deficits, whereas the enhancement function involves maintaining or growing self-views (Clary et al. 1998).

First, we propose charitable actions performed by materialistic consumers result from protecting their egos. Extant research reveals that consumers with low self-views (i.e., low self-esteem) are more prone to being materialistic (Park and John 2010) and that materialistic consumers value security (Gurel-Atay et al. 2014). Further validating materialism as a coping factor, Segev et al. (2015) find positive correlations among depression and negative affect and materialism. That is, feelings of depression and negative affect lead consumers to be more materialistic. As such, materialistic consumers may engage in charitable behaviors to eliminate these negative self-views and to deal with uncertainty (Chang and Arkin 2002; Micken and Roberts 1999). Likewise, we anticipate that those who are more materialistic may feel guilt for their emphasis on possessions and thus, the protective motive may account for why materialistic consumers engage in charitable behavior.

Second, because extant research finds a positive relationship between self-enhancement and materialism (Ger and Belk 1996, 1999; Karabati and Cemalcilar 2010; Kilbourne et al. 2005; Shrum et al. 2013), we suggest that Clary et al.’s (1998) enhancement motivation may also relate to materialism as an aid in developing one’s identity and enhancing well-being. That is, materialistic consumers desire social recognition and being well-respected within society (Gurel-Atay et al. 2014), thus, a self-enhancement motive may underlie materialistic consumers’ charitable behaviors. This suggests that materialism could also work through an enhancement motivation to enhance social recognition and/or one’s individual uniqueness.

We suggest that Clary et al.’s (1998) other motives (values, understanding, social, and career) will not account for the positive relationship between materialism and charitable behavior intentions. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses (as illustrated in Fig. 1):

Hypothesis 1a

There is a positive relationship between materialism and protection motivation.

Hypothesis 1b

There is a positive relationship between protection motivation and charitable behavior intentions.

Hypothesis 1c

Protection motivation mediates the relationship between materialism and charitable behavior intentions.

Hypothesis 2a

There is a positive relationship between materialism and enhancement motivation.

Hypothesis 2b

There is a positive relationship between enhancement motivation and charitable behavior intentions.

Hypothesis 2c

Enhancement motivation mediates the relationship between materialism and charitable behavior intentions.

Gratitude

Studies have indicated that gratitude and materialism are inversely related consumer variables (Lambert et al. 2009; McCullough et al. 2002). As discussed by Lambert et al. (2009), this negative relationship can be explained as a result of the key foci of these constructs. Materialistic consumers tend to focus on the self and what one does not have, while grateful consumers tend to focus on others and on what one does have. The inverse relationship shared between these two consumer traits indicates that gratitude and materialism may motivate charitable behaviors through different mechanisms.

Gratitude, as a trait, refers to a “generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains” (McCullough et al. 2002, p. 112). Gratitude is a valued trait within several religions, and expressions of gratitude exist in nearly every language (Emmons and Crumpler 2000; McCullough et al. 2001). Despite its pervasiveness, until the early 2000s, gratitude research was virtually nonexistent. In fact, Wood et al. (2010, p. 891) describe gratitude as a “key underappreciated trait in clinical psychology.” Only recently have psychology and marketing scholars acknowledged the critical role of gratitude in everyday life occurrences.

McCullough et al.’s (2002) definition considers the grateful disposition as maintaining four facets—intensity, frequency, span, and density. These facets imply that compared to individuals low in gratitude, highly grateful individuals experience more intense feelings of gratitude, feel gratitude more frequently, appreciate a larger amount of life experiences, and are thankful to a larger number of individuals for a sole positive experience. Similar to these facets, other scholars describe grateful individuals as having a sense of abundance, an appreciation for the simple pleasures in life and others’ contributions to one’s well-being, and a belief that expressions of gratitude are important (Watkins et al. 2003).

Empirical evidence validates that grateful individuals readily experience thankfulness, and reveals that this phenomenon is explained by the positive benefit appraisals undertaken when receiving a benefit (McCullough et al. 2002; Wood et al. 2008). Compared to others, individuals scoring high on trait gratitude perform more positive benefit appraisals, such that when receiving a benefit, these individuals appraise the help as more valuable, more costly to provide, and more benevolently motivated, all of which drive feelings of gratefulness (Wood et al. 2008).

Moral affect theory describes gratitude as maintaining three functions (McCullough et al. 2001). First, gratitude functions as a moral barometer by being a response to the recognition of another individual’s moral behaviors. Second, gratitude maintains a moral motive function by prompting grateful individuals to perform positive behaviors directed toward one’s benefactor and other individuals. Third, gratitude functions as moral reinforcer, such that expressions of thankfulness encourage benefactors to perform moral behaviors in the future.

Most relevant to the current research, is the moral motivator function, which has been empirically validated in the literature by linking gratitude to prosocial behaviors directed toward one’s benefactor and toward strangers (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006). Equally important, is the wide array of prosocial behaviors gratitude promotes. For instance, gratitude has been positively linked to helping others, returning favors (Emmons and McCullough 2003; Li and Chow 2015; Romani et al. 2013), and most recently, consumer support for nonprofits—operationalized as the likelihood of joining, donating money to, and actively participating in nonprofits (Xie and Bagozzi 2014). Furthermore, in comparison to happiness, gratitude appears to be a stronger predictor of helping others and helping others voluntarily (Hui et al. 2015).

Examining the diverse motivations for charitable giving reveals one motivation, the values motivation, as relevant to consumers scoring high on trait gratitude. The values motivation implies that consumers engage in charitable behaviors to express their humanitarian concern for others (Clary et al. 1998). In accordance with the moral motivator function of gratitude, grateful individuals are concerned about others, and engage in a wide array of prosocial behaviors due to being motivated to help others (Emmons and McCullough 2003; McCullough et al. 2001; Romani et al. 2013; Xie and Bagozzi 2014). Thus, we anticipate that grateful individuals perform charitable behaviors to genuinely express their altruistic concern for others (rather than maintaining more self-serving motives), and that the consumer trait of gratitude does influence charitable behavior intentions, but this influence is mediated by one’s values motivation, as illustrated by the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a

There is a positive relationship between gratitude and values motivation.

Hypothesis 3b

There is a positive relationship between values motivation and charitable behavior intentions.

Hypothesis 3c

Values motivation mediates the relationship between gratitude and charitable behavior intentions.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Undergraduates at a major state university participating in a subject-pool for course credit recruited 231 adults to participate in the survey. Each student recruited 1–3 adults (i.e., nonstudents) to participate. The average age was 44.43 years, and 57 % of the participants were female. The majority of the participants were Caucasian, representing 78.7 % of the sample, 11.7 % were African American, 3.5 % were Hispanic, 3.5 % were Asian, and less than 1 % were Native American or Pacific Islander. Participants maintained diverse annual household incomes, ranging from under $20,000 to over $150,000, with 50 % of the sample indicating household incomes above or below the 100,000–109,999 range. Data were gathered through an online survey platform. After obtaining informed consent, participants were asked whether they had volunteered or donated within the past year, and if so, the type of donation, including time, money, and gifts. Participants who had volunteered or donated within the past year were presented the following measures.

Measures

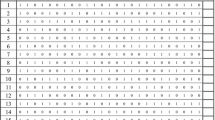

All measures utilized a 7-point scale unless noted otherwise. After ensuring acceptable psychometric properties and internal consistency (Nunnally 1978), average composite scores were created for each construct. See Table 1 for all measures.

Volunteer/Donation Motivations

We adapted Clary et al.’s (1998) six-dimensional volunteer functions inventory by including charitable donations in the instructions. Specifically, we asked participants “to please indicate how important or accurate each of the following reasons are for you in doing volunteer work or providing charitable donations.” Each of the items was anchored by “not at all important or not at all accurate” to “extremely important or extremely accurate.”

Charitable Behavior Intentions

We assessed charitable behavior intentions by the item “Overall, how likely is it that you will donate or volunteer in the future,” anchored by “very unlikely” to “very likely.”Footnote 1 Participants were asked donation or volunteer intentions together since Apinunmahakul et al. (2009) suggest that donating time versus money are largely complements rather than substitutes. Moreover, this operationalization is consistent with extant research, which has measured consumer support for nonprofits as one’s intent to join, donate money, and actively participate in nonprofits (Xie and Bagozzi 2014).

Gratitude

Trait gratitude was assessed using the six-item GQ-6 Likert scale developed by McCullough et al. (2002). Typical of reverse coded items (Weijters and Baumgartner 2012), the two reverse coded gratitude items failed to adhere to the recommended psychometric criteria, and thus were removed from subsequent analyses.

Materialism

Materialism has been measured by Belk (1985), Richins and Dawson (1992), and Sirgy et al. (2012). Given the reliability issue with Belk’s (1985) scale (Ger and Belk 1990, 1996; Richins and Dawson 1992) and the issues with Richins and Dawson’s (1992) scale (Flynn et al. 2013; Goldsmith et al. 2012; Griffin et al. 2004; Kilbourne et al. 2005; Strizhakova and Coulter 2013; Tobacyk et al. 2011), we chose to utilize Sirgy et al.’s (2012) nine-item materialism Likert scale as a unidimensional construct.

Controls and Marker Constructs

We included a four-item Likert scale measuring one’s attitude toward charitable organizations, as extant research has associated attitudes with charitable behavior (Webb et al. 2000). We also controlled for consumers’ desire to be recognized for charitable acts (hereafter recognition; Winterich et al. 2013), as materialism has been associated with utilizing consumption to demonstrate success (Podoshen and Andrzejewski 2012; Richins and Dawson 1992). Lastly, a three-item Likert scale of financial inadequacy (Wiepking and Breeze 2012) was included as a marker variable to assess common method variance.

Results

The majority of the sample had donated (91.8 %) or volunteered (63.6 %) within the past year. Since the focus was to understand motivations for donating or volunteering, only data obtained from participants donating or volunteering within the past year were used in the subsequent analyses. This created a useable sample of 216 participants.

Common Method Bias

Common method bias was considered ex ante and ex post. Prior to gathering the data, the researchers ensured that all items were worded within the participants’ frame of reference and, as a precautionary measure, the survey did not present constructs in the hypothesized order. After data collection, common method bias was assessed by the Harman’s single-factor test and through the marker variable technique (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Following the Harman’s single-factor test, all items representing latent constructs were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis. Examining the unrotated factor solution revealed that the majority of the variance could not be explained by a single-factor, indicating that common method bias failed to contaminate the data. To further assess common method bias, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) including financial inadequacy as marker variable was performed. The results of this technique revealed that less than 7.6 % of the variance was shared among the constructs, further substantiating that common method variance failed to influence the interpretation of the data.

Construct Validity

We then ran CFA including the theoretically related constructs to ensure construct validity and discriminant validity. With the exception of attitude toward charitable organizations, the results confirmed construct validity, such that estimates of average variance extracted exceeded the criterion of .50 and all composite reliabilities surpassed .70 (Hair et al. 2010). The constructs also indicated discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Despite the high association between protection and enhancement motivation (ρ = .86), which is anticipated since both motives focus on the ego (Clary et al. 1998), constraining their relationship indicated significantly worse fit (∆χ2 = 6.86, p < .05), supporting discriminant validity between protection and enhancement motivations (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). As expected, a marginally significant negative correlation was shared between gratitude and materialism (ρ = −.14; p = .056), substantiating extant work revealing the opposing nature between these two traits (Lambert et al. 2009). See Table 2 for all construct correlations.

Hypothesis Testing

We conducted multiple mediator testing (Preacher and Hayes 2008) using the PROCESS macro to test two models, one for materialism and another for gratitude. Bootstrapped estimates of the indirect effects were utilized since this technique is appropriate for small sample sizes and offers several advantages by directly estimating the size of the indirect effects, in addition to offering confidence intervals of the effects and establishing higher power and more control over Type 1 error (Preacher et al. 2007). The effects were calculated to obtain a 95 % confidence interval with 10,000 samples, using income, attitude toward charitable organizations, and recognition as control variables.

We first tested the predictions that protection and enhancement motives mediate the relationship between materialism and charitable behavior intentions. As predicted, materialism positively influenced protection motivation (b = .25, SE = .09, t = 2.69 p < .05, CI .07–.44), and protection motivation positively influenced charitable behavior intentions (b = .24, SE = .09, t = 2.72, p < .05, CI .07–.41), thus supporting H1a and H1b. In support of H1c, the indirect effect (IE) of materialism on charitable behavior intentions through protection motivation was significant (p < .05), with a 95 % confidence interval from .01 to .16. The results also offered support for H2a, such that materialism positively affected enhancement motivation (b = .37, SE = .10, t = 3.70, p < .05, CI .17–.56). However, the results failed to support H2b and H2c, as enhancement motivation had no effect on charitable behavior intentions (b = −.15, SE = .08, t = −1.85, p > .05, CI −.32 to .01), and the indirect effect through enhancement was nonsignificant (p > .05), with a 95 % confidence interval from −.16 to .002.

As a supplemental test of our hypotheses, we performed a post hoc analysis that included the other, nonhypothesized motivations (i.e., values, understanding, social, and career), as mediators between materialism and charitable intentions. With the exception of the values motivation, the indirect effects were nonsignificant (p > .05), indicating that these other motives did not account for the positive relationship between materialism and charitable behavior intentions. The 95 % confidence interval for the indirect effect of materialism on charitable behavior intentions through values orientation did not include zero (−.07 to −.003). Materialism negatively influenced the values orientation (b = −.12, SE = .06, t = −1.89, p = .06, CI −.24–.005) and values orientation positively influenced charitable behavior intentions (b = .22, SE = .10, t = 2.06, p < .05, CI .01–.42). This finding corroborates the notion that materialism affects charitable behaviors positively through more egoistic, self-serving motivations, than through an altruistic, self-sacrificing motivation (Table 3).

Using the PROCESS macro, a second model including income, attitude toward charitable organizations, and recognition as control variables was also used to test hypotheses pertaining to gratitude (H3a–H3c). Results from bootstrapping indicated support for H3a, such that trait gratitude positively impacted values motivation (b = .19, SE = .09, t = 2.15, p < .05, CI .02–.36) and support for H3b, as values motivation positively impacted charitable behavior intentions (b = .20, SE = .09, t = 2.14, p < .05, CI .02–.38).Footnote 2 Examining the indirect effects revealed a significant indirect effect of trait gratitude on charitable behavior intentions through values motivation, with a 95 % confidence interval ranging from .001 to .13, therefore supporting H3c.

A post hoc analysis, including the other, nonhypothesized motivations (i.e., protection, enhancement, understanding, social, and career) as mediators between gratitude and charitable intentions, confirmed the values motivation as the key explanatory mechanism. As expected, the 95 % confidence intervals for the indirect effects through the other nonhypothesized motives contained zero, indicating that these other motives did not account for the relationship between gratitude and charitable behavior intentions. These findings confirm that gratitude influences charitable behaviors through altruistic rather than self-serving motives.

Discussion

The research herein reveals that two vastly different traits, materialism and gratitude, can both positively influence charitable behaviors though operating through very different motivations. Our results offer significant implications for theory and practice as well as indicate needed areas of research.

Implications

Charitable giving within the United States represents a significant amount of time and money. Organizations rely on consumers’ charitable behaviors, yet to encourage a continuance of giving, organizations need a more precise understanding of consumer traits and motivations driving these behaviors (Pitt et al. 2001). The current research contributes to the literature and practice by exploring relationships between donor motives and type of charitable behavior and by empirically testing the relationships among consumer traits, motives, and charitable behavior intentions. Extant research reveals that one consumer trait, materialism, can influence charitable behaviors, with a positive direct effect and a negative indirect effect (Mathur 2013), suggesting the need for a more complete theoretical framework (Zhao et al. 2010). We theorized consumer motivations as explanatory mechanisms, and empirically confirmed that distinct motivations can account for the effects of two inversely related consumer traits—materialism and gratitude—on charitable behavior.

Extant research reveals difficulty in explaining the relationship between materialism and charitable behavior (Mathur 2013; O’Reilly et al. 2012). This study contributes to the literature by providing an explanation for why materialistic consumers give to charities. Rather than attempting to make one look better to others or to enhance one’s identity (Ger and Belk 1996, 1999; Karabati and Cemalcilar 2010; Kilbourne et al. 2005; Shrum et al. 2013), we suggest materialistic consumers donate to aid in protecting their egos. That is, for materialistic consumers, charitable giving may have an instrumental purpose in reducing uncertainty or negative feelings consumers may have about themselves. These results suggest that highly materialistic consumers are motivated by a more egoistical, self-serving motive, and that this is occurring through a protection function rather than an enhancement function. This finding suggests that materialism appears to be operating instrumentally rather than terminally.

Per social exchange theory, materialistic consumers are seeking a reward in exchange for their behavior toward charities (Thibaut and Kelley 1959). Our research suggests that the reward the donors are seeking in their exchange relationship with charities is relieving guilt and uncertainty rather than enhancing oneself in terms of feeling important or enhanced social interaction. This instrumental aspect of materialism (Ger and Belk 1999), in which consumers are utilizing charitable behaviors as means to feel better about themselves, may illustrate a positive aspect of materialism.

In relating back to Mathur’s (2013) question of how materialism and generosity can co-exist, our research suggests that it does so through a protection motivation (i.e., materialistic consumers give to feel better about themselves by relieving guilt and trying to reduce uncertainty in their lives). Research illustrates that materialistic people are associated with a sense of insecurity, which is why they try to utilize possessions to bring happiness (Ger and Belk 1996; Sangkhawasi and Johri 2007). Likewise, consumers who are depressed and/or have negative affect utilize materialism as a coping mechanism (Segev et al. 2015). Research also suggests that individuals with low self-concept clarity and low self-efficacy may attribute control to others and then utilize materialism as a means of gaining control (Watson 2014). Our findings suggest that charitable behaviors may aid materialistic consumers in dealing with this sense of insecurity or guilt by providing a means of gaining control over oneself, rather than as a means to enhance oneself or to look better to others.

We did not find enhancement to mediate the effect of materialism on charitable behavior. These results suggest that the intention to give to charities is not motivated by looking better or affiliating with others socially and, consequently, that the social aspect of materialism (social recognition) is not at work in explaining the impact of materialism on charitable behaviors. We found, similar to the literature, that materialism functions as means to enhance oneself (Richins and Dawson 1992; Richins 1994), but our results found that this enhancement motivation will not be demonstrated through charitable behavior, which suggests the terminal view of enhancement through possessions (Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton 1978, 1981; Richins and Dawson 1992; Sirgy et al. 1998).

Our results lead to the recommendation that nonprofits should not promote the idea of encouraging donors to get their friends involved with their charitable causes, particularly for those consumers who are more materialistic. White and Peloza (2009) suggest that a self-benefit (in terms of resume building or networking, social opportunities) is less effective than any other-benefit (helping the less fortunate and making the community a better place) in a public context. These results along with our findings are interesting because this is a tactic that some nonprofits have utilized in relying on people buying products from people they know (such as charities selling candy/popcorn, magazines, gift wrap) or requesting that people ask friends for donations. Another possible explanation for why there was not a significant result with the enhancement motivation may be seen with Lemrova et al.’s finding (2014, p. 329) that “those who pursue materialism cherish achievement (vanity), but budget their money poorly”.

Thus, a contribution of this research is to illustrate the potential impact of materialism on charitable behaviors through a protective motivation. It extends the stream of research relating materialism to consumers’ feelings of uncertainty (Chang and Arkin 2002; Micken and Roberts 1999; Shrum et al. 2013) by illustrating a positive impact of materialism on charitable behaviors, and aids in explaining Mathur’s (2013) results. Given that materialism significantly impacted charitable behaviors through a protection rather than an enhancement motivation, we conclude that materialism positively impacts charitable giving as a result of instrumental materialism (i.e., to achieve some higher end such as enhancing one’s sense of control through reducing uncertainty and guilt), rather than terminal materialism (i.e., to create envy and increase one’s status). However, future research incorporating a thorough measurement of instrumental and terminal materialism (Gurel-Atay et al. 2014) is needed to measure this directly.

Since grateful consumers appreciate what life has to offer, it is no surprise that gratitude has been positively linked to ethics, corporate social responsibility (Andersson et al. 2007), and support for nonprofits (Xie and Bagozzi 2014). While research on gratitude has recently flourished, to the authors’ knowledge no research has examined how trait gratitude influences charitable giving. Consistent with moral affect theory of gratitude and gratitude’s function as a moral motivator (McCullough et al. 2001), we find that grateful consumers intend to continue their charitable behaviors as a means to express their genuine concern for others. That is, grateful individuals perform charitable behaviors as a more agapic action toward another rather than a social exchange (Pitt et al. 2001), as these consumers are motivated to engage in prosocial behaviors that benefit others, including strangers (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006). While this is the first research examining these relationships with gratitude, it marks a significant contribution and encourages future research on priming or developing consumer gratitude to encourage charitable acts. Moreover, the results herein encourage future research to further understand the relationship between gratitude and charitable and ethical behaviors by incorporating other variables such as religiousness. Extant research associates gratitude with religiousness (McCullough et al. 2002), and intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness have been demonstrated to impact consumer ethics, with intrinsic religiousness having a more positive impact on consumer ethics than extrinsic religiousness (Arli and Tjiptono 2014). These findings highlight the importance of additional research on gratitude’s association with other charitable and ethical behaviors.

Charitable organizations need to recognize the importance of consumer gratitude. The results herein reveal gratitude’s key association with charitable behavior, which extends the rich array of prosocial behaviors associated with grateful consumers (Emmons and McCullough 2003; McCullough et al. 2001; Romani et al. 2013). To attract this consumer segment, our findings encourage charitable organizations to utilize empathy appeals and emphasize the importance of helping others. Thus, we recommend that charitable organizations focus their appeals on the positive impact donors can make by helping others, rather than appealing to social or enhancement benefits for the donors themselves.

Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of this study is that our operationalization of charitable behavior intentions measured the likelihood to donate (e.g., money) or volunteer (e.g., time) simultaneously, rather than separately. Although extant research suggests that donating time versus money are complements (Apinunmahakul et al. 2009), it would be beneficial for future research to determine if the relationships we found between materialism, gratitude, charitable motivations, and charitable behavior vary based upon whether the behavior studied includes donating time versus donating money. Reed et al. (2007) suggest that by priming moral identities, consumers are more likely to prefer giving time than money, and this preference is even stronger when the organization is one that assists others in need (i.e., when the time given has a moral purpose). This suggests that charities need to utilize their communications to prime donors in terms of the charitable behaviors needed (i.e., time versus money). Consequently, it would be insightful for future experimental research to determine how a moral identity prime impacts time versus money donations given consumers’ motivations for charitable behaviors.

Another limitation of our study is that we examined charitable behaviors in terms of likelihood rather than magnitude of time and/or money donated. Extant research suggests that charitable giving amounts are influenced by the time-ask effect (i.e., asking individuals how much time they would like to donate, rather than how much money, enhances the amounts of charitable donations; Liu and Aaker 2008). Given the substantive importance of donation magnitude, additional research is necessary to examine how the consumer traits and motivations studied herein affect the amounts of charitable donations. Similarly, we considered motivations for giving as operating independently. Nonetheless, it is possible for consumers to possess multiple motivations simultaneously, and for these motivations to interact with each other.Footnote 3 While these issues were outside the scope of the current study, additional research is warranted to examine these possibilities.

Our result that materialism impacts charitable behaviors through an ego-protection motivation suggests that charities need to illustrate how consumers can make a difference and improve society, rather than merely look better to others. Future research could examine the effectiveness of different charitable behavior tactics given one’s level of materialism and/or gratitude, such as through extending the work of White and Peloza (2009) of self-benefit versus other-benefit appeals. That is, future research could examine whether donors’ reactions to self- or other-benefit appeals differ across consumer traits. Future research is also needed to examine these results in more detail; for example, to explore more specifically whether it is instrumental or terminal materialism impacting motivations for charitable behaviors. Finally, future research could use social exchange theory to better understand charitable behaviors. For example, researchers could extend the work of Shehu et al. (2015) by examining how charitable motives relate to trust, brand personality of nonprofits, and incentives for giving. Thus, while the research offers a more complete look at how the opposing constructs of materialism and gratitude can both impact charitable behaviors through the mediating influence of charitable motivations, more research is needed to better define this influence in terms of specific charitable behaviors.

Notes

Rather than measuring donation magnitude, we adhered to the stream of academic research examining intentions, which has been extended specifically to charitable giving (Ein-Gar and Levontin, 2013; White and Peloza, 2009; Xie and Bagozzi, 2014). Extant research also indicates that participants may be unable to remember exact donation amounts and that such measures lend themselves to increased social desirability bias (Mathur, 1996).

Path analysis revealed similar path estimates.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Andersson, L. M., Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2007). On the relationship of hope and gratitude to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 70, 401–409.

Apinunmahakul, A., Barham, V., & Devlin, R. A. (2009). Charitable giving, volunteering, and the paid labor market. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(1), 77–94.

Arli, D., & Tjiptono, F. (2014). The end of religion? Examining the role of religiousness, materialism, and long-term orientation on consumer ethics in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 123, 385–400.

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17(4), 319–325.

Bazilian, E. (2012). Charity: The new status symbol? Adweek , 53(36), 14.

Belk, R. W. (1984). Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. Advances in Consumer Research , 11(1), 291–297.

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(December), 265–279.

Belk, R. W., & Coon, G. S. (1993). Gift giving as agapic love: An alternative to the exchange paradigm based on dating experiences. Journal of Consumer Research , 20(3), 393–417.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (1997). Materialism as a coping mechanism: An inquiry into family disruption. Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 89–97.

Chang, L. C., & Arkin, R. M. (2002). Materialism as an attempt to cope with uncertainty. Psychology and Marketing, 19(5), 389–406.

Charities Aid Foundation. (2014). World giving index 2014: A global view of giving trends.

Chowdhury, R. M. M., & Fernando, M. (2013). The role of spiritual well-being and materialism in determining consumers’ ethical beliefs: An Empirical study with Australian consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 61–79.

Christopher, A. N., Drummond, K., Jones, J. R., Marek, P., & Therriault, K. M. (2006). Beliefs about one’s own death, personal insecurity, and materialism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 441–451.

Clark, I, I. I. I., & Micken, K. S. (2002). An exploratory cross-cultural analysis of the value of materialism. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 14(4), 65–89.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Meine, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1516–1530.

Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Papadopoulos, N. (2009). Cosmopolitanism, consumer ethnocentrism, and materialism: An eight country study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of International Marketing, 17(1), 116–146.

Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., & Papadopoulos, N. (2011). Ethnic identity’s relationship to materialism and consumer ethnocentrism: Contrasting consumers in developed and emerging economies. Journal of Global Academy of Marketing Science, 21(2), 55–71.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1978). Reflections on Materialism. University of Chicago Magazine, 70(3), 6–15.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The meaning of things: Domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ein-Gar, D., & Levontin, L. (2013). Giving from a distance: Putting the charitable organization at the center of the donation appeal. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 197–211.

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 56–69.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(February), 377–389.

Flynn, L. R., Goldsmith, R. E., & Kim, W.-M. (2013). A cross-cultural study of materialism and brand engagement. Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 5(3), 49–69.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(February), 39–50.

Ger, G., & Belk, R. W. (1990). Measuring and comparing materialism cross-culturally. Advances in Consumer Research, 17(1), 186–192.

Ger, G., & Belk, R. W. (1996). Cross-cultural differences in materialism. Journal of Economic Psychology, 17, 55–77.

Ger, G., & Belk, R. W. (1999). Accounting for materialism in four cultures. Journal of Material Culture, 4(2), 183–204.

Goldsmith, R. E., Flynn, L. R., & Clark, R. (2012). The dimensions of materialism: A comparative analysis of four materialism scales. Advances in Psychological Research, 91, 109–122.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review , 25(2), 161–178.

Griffin, M., Babin, B. J., & Christensen, F. (2004). A cross-cultural investigation of the materialism construct in assessing the Richins and Dawson’s materialism scale in Denmark, France, and Russia. Journal of Business Research, 57, 893–900.

Gurel-Atay, E., Sirgy, M. J., Webb, D., Ekici, A., Lee, D.-J., Cicic, M., et al. (2014). What motivates people to be materialistic? Developing a measure of instrumental-terminal materialism. Advances in Consumer Research, 42, 502–503.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Harbaugh, W. T. (1998). The prestige motive for making charitable transfers. The American Economic Review, 88(2), 277–282.

Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606.

Hudders, L. (2012). Why the devil wears Prada: Consumers’ purchase motives for luxuries. Journal of Brand Management, 19(7), 609–622.

Hui, Q.-P., He, A.-M., & Liu, H.-S. (2015). A situational experiment about the relationship among gratitude, indebtedness, happiness and helping behavior. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 29(11), 852–857.

Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. (2014). Giving USA 2014: The annual report on philanthropy for the year 2013. Published by Giving USA Foundation.

Josuh, W. J., Wan, J.-G. H., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2001). Self-ratings of materialism and status consumption in a Malaysian sample: Effects of answering during an assumed recession versus economic growth. Psychological Reports, 88, 1142–1144.

Karabati, S., & Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Values, materialism, and well-being: A study with Turkish University Students. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31, 624–633.

Khalil, E. L. (2004). What is altruism? Journal of Economic Psychology, 25, 97–123.

Kilbourne, W., Grunhagen, M., & Foley, J. (2005). A cross-cultural examination of the relationship between materialism and individual values. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26, 624–641.

Kilbourne, W., & Pickett, G. (2008). How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61, 885–893.

Kumru, C. S., & Vesterlund, L. (2010). The effect of status on charitable giving. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 12(4), 709–735.

Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Stillman, T. F., & Dean, L. R. (2009). More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 32–42.

Lemrova, S., Reiterova, E., Fatenova, R., Lemr, K., & Tang, T. L.-P. (2014). Money is power: Monetary intelligence-love of money and temptation of materialism among Czech University Students. Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 329–348.

Li, K.-K., & Chow, W.-Y. (2015). Religiosity/spirituality and prosocial behaviors among Chinese christian adolescents: The mediating role of values and gratitude. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(2), 150–161.

Liu, W., & Aaker, J. (2008). The happiness of giving: The time-ask effect. Journal of Consumer Research, 35, 543–557.

Lu, L.-C., & Lu, C.-J. (2010). Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: An exploratory study in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 193–2010.

Mathur, A. (1996). Older adults’ motivations for gift giving to charitable organizations: An Exchange Theory Perspective. Psychology and Marketing, 13(1), 107–123.

Mathur, A. (2013). Materialism and charitable giving: Can they co-exist? Journal of Consumer Behavior, 12, 149–158.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(March), 249–266.

Micken, K. S., & Roberts, S. D. (1999). Desperately seeking certainty: Narrowing the materialism construct. Advances in Consumer Research, 26, 513–518.

Muncy, J. A., & Eastman, J. K. (1998). Materialism and consumer ethics: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 137–145.

Munoz-Garcia, F. (2011). Competition for status acquisition in public good games. Oxford Economic Papers, 63, 549–567.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

O’Reilly, N., Ayer, S., Pegoraro, A., Leonard, B., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2012). Toward an understanding of donor loyalty: Demographics, personality, persuasion, and revenue. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 24, 65–81.

Osili, U. O., Hirt, D. E., & Raghavan, S. (2011). Charitable giving inside and outside the workplace: The role of individual and firm characteristics. International Journal of Nonprofits and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 16, 393–408.

Park, J. K., & John, D. R. (2010). More than meets the eye: The influence of implicit and explicit self-esteem on materialism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21, 73–87.

Pitt, L., Keating, S., Bruwer, L., Murgolo-Poore, M., & de Bussy, N. (2001). Charitable donations as social exchange or agapic action on the internet: The case of Hungersite.com. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 9(4), 47–61.

Pitt, R. E., & Skelly, G. U. (1984). Economic self-interest and other motivational factors underlying charitable giving. Journal of Behavioral Economics, 12(2), 93–109.

Podoshen, J. S., & Andrzejewski, S. A. (2012). An examination of the relationships between materialism, conspicuous consumption, impulse buying, and brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 20(3), 319–333.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227.

Prendergast, G. P., & Maggie, C. H. W. (2013). Donors’ experience of sustained charitable giving: a phenomenological study. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(2), 130–139.

Reed, I. I., Americus, K. A., & Levy, E. (2007). Moral Identity and Judgments of Charitable Behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 71(January), 178–193.

Richins, M. L. (1994). Special possessions and the expression of material values. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(December), 522–533.

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 303–316.

Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Bagozzi, R. (2013). Explaining consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of gratitude and altruistic values. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 193–206.

Sangkhawasi, T., & Johri, L. M. (2007). Impact of status brand strategy on materialism in Thailand. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(5), 275–282.

Schlegelmilch, B. B., Love, A., & Diamantopoulos, A. (1997). Responses to different charity appeals: The impact of donor characteristics on the amount of donations. European Journal of Marketing , 31(7/8), 548–560.

Segev, S., Shoham, A., & Gavish, Y. (2015). A closer look into the materialism construct: The antecedents and consequences of materialism and its three facets. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 32(2), 85–98.

Shehu, E., Becker, J. U., Langmaack, A.-C., & Clement, M. (2015). The brand personality of nonprofit organizations and the influence of monetary incentives. Journal of Business Ethics,. doi:10.1007/510551-015-2593-3.

Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., et al. (2013). Reconceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66, 1179–1185.

Sirgy, M. Joseph, Gurel-Atay, E., Webb, D., Cicic, M., Husic, M., Ekici, A., et al. (2012). Linking advertising, materialism, and life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 107, 79–101.

Sirgy, M. J., Lee, D.-J., Kosenko, R., Meadow, H. L., Rahtz, D., Cucic, M., et al. (1998). Does television viewership play a role in the perception of quality of life? Journal of Advertising, 27(1), 125–142.

Strizhakova, Y., & Coulter, R. A. (2013). The ‘Green’ Side of Materialism in Emerging BRIC and Developed Markets: The Moderating Role of Global Cultural Identity. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 30, 69–82.

Thibaut, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley Publishing.

Tobacyk, J. J., Babbin, B. J., Attaway, J. S., Socha, S., Shows, D., & James, K. (2011). Materialism through the eyes of polish and American consumers. Journal of Business Research, 64, 944–950.

Unanue, W., Dittmar, H., Vignoles, V. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2014). Materialism and well-being in the UK and Chile: Basic need satisfaction and basic need frustration as underlying psychological processes. European Journal of Personality, 28(6), 569–585.

Van Leeuwen, M. H. D., & Wiepking, P. (2013). National campaigns for charitable causes: A literature review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(2), 219–240.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(5), 431–452.

Watson, D. C. (2014). A model of the materialistic self. North American Journal of Psychology, 16(1), 137–158.

Webb, D. J., Green, C. L., & Brashear, T. G. (2000). Development and validation of scales to measure attitudes influencing monetary donations to charitable organizations. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 299–309.

Weidmann, K.-P., Hennigs, N., & Siebels, A. (2009). Value-based segmentation of luxury consumption behavior. Psychology and Marketing, 26(7), 625–651.

Weijters, B., & Baumgartner, H. (2012). Misresponse to reversed and negative items in surveys: A review. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(5), 737–747.

White, K., & Peloza, J. (2009). Self-benefit versus other-benefit marketing appeals: Their effectiveness in generating charitable support. Journal of Marketing, 73, 109–124.

Wiepking, P., & Breeze, B. (2012). Feeling poor, acting stingy: The effect of money perceptions on charitable giving. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17(1), 13–24.

Winterich, K. P., Mittal, V., & Aquino, K. (2013). When does recognition increase charitable behavior? Toward a moral identity-based model. Journal of Marketing, 77(May), 121–134.

Wong, N. Y. C. (1997). Suppose you own the world and no one knows? Conspicuous consumption, materialism, and self. Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 197–203.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, Adam W. A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890–905.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Neil Stewart, P., Linley, A., & Joseph, S. (2008). A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion, 8(2), 281–290.

Xie, C., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2014). The role of moral emotions and consumer values and traits in the decision to support nonprofits. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing, 26, 290–311.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G, Jr, & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bock, D.E., Eastman, J.K. & Eastman, K.L. Encouraging Consumer Charitable Behavior: The Impact of Charitable Motivations, Gratitude, and Materialism. J Bus Ethics 150, 1213–1228 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3203-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3203-x