Abstract

Despite growing interest in emotions, organizational scholars have largely ignored the moral emotion of schadenfreude, which refers to pleasure felt in response to another’s misfortune. As a socially undesirable emotion, it might be assumed that individuals would be hesitant to share their schadenfreude. In two experimental studies involving emotional responses to unethical behaviors, we find evidence to the contrary. Study 1 revealed that subjects experiencing schadenfreude were willing to share their feelings, especially if the misfortune was perceived to be deserved (i.e., resulting from unethical behaviors). Study 2 extends this work by incorporating schadenfreude targets of different status (CEO versus employee). Consistent with the “tall poppy syndrome,” subjects were more willing to share schadenfreude concerning high status targets than low status targets when the perceived severity of the target’s misconduct was low. This status effect disappeared at higher levels of perceived deservingness, however. Reported willingness to share schadenfreude was strongest at these levels but did not differ significantly between high and low status targets. These findings build on the social functional account of emotions, suggesting that sharing schadenfreude may signal normative cues to others regarding workplace behaviors that are deemed to be unethical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Unlike most things that light up your ventral striatum [a region in the brain], schadenfreude is free, it’s not fattening, and you don’t have to take your clothes off. It can’t hurt, and it just might make you feel a little better. (Zweig 2009 The Wall Street Journal Online)

Much of our early understanding of organizational ethics relied on a cognitive perspective (Treviño et al. 2006). More recently, business ethics scholars have shown increased interest in the role of affect, with emotions now playing a central role in moral psychology research (Greene 2011). Moral emotions, such as guilt and anger in particular, have become a focus of this research (Horberg et al. 2011). In this article, we respond to the call by Lindebaum and Jordan (2012) to focus on the utility of discrete emotions as they relate to varying contexts. More specifically, we present conceptual and empirical evidence that the little-studied moral emotion of schadenfreude can further our understanding of how employees react to ethically questionable behaviors of others. We further propose that context (high and low status, ethical versus unethical behaviors) serves as a boundary condition for when this emotion is shared with others.

Schadenfreude is a German term that describes feelings of pleasure that a person experiences in response to another person’s failures or misfortunes (Feather 2006; Heider 1958). German immigrants first introduced the term schadenfreude to the USA following publication of Wilhelm Busch’s book about the pranks of “Max and Moritz” in 1865. Schadenfreude is a social emotion, as it relates to the misfortunes of other people (Parkinson and Manstead 2015). Because it is a response specific to negative outcomes, despite being a pleasurable feeling, this emotion has been described as undesirable, objectionable (McNamee 2003; 2007), and malicious (Leach et al. 2003).

While schadenfreude has been mentioned frequently in the popular press and social media (see Kramer et al. 2011; Leach et al. 2014), and some progress has been made within social psychology (e.g., Brigham et al. 1997; Feather and Nairn 2005; Feather and Sherman 2002), it has received scant attention in the organizational literature. This is unfortunate, as any social situation that involves competition, comparison, or collaboration may involve complex social emotions such as schadenfreude (Heider 1958). Hence, we expect that this emotion is frequently present in the workplace, although individual employees may not feel comfortable admitting it.

Through a search of the PsycArticles and ScienceDirect databases we identified only four published articles that focused on schadenfreude in organizational settings. In the applied social psychology literature, it has been examined within the context of selection and promotion decisions (Feather 2008b; Feather et al. 2011). In these articles, the perceived deservingness of individuals’ misfortune (failure to be selected or promoted) was the main predictor of schadenfreude. In the organizational literature, we found two articles that focused primarily on the impact of schadenfreude on individual judgments and decision making. Wiesenfeld et al. (2008) explained that schadenfreude is likely to bias judgments about business elites tainted by corporate failure. Consistent with the notion that anticipated emotion can impact behavioral choices in a manner similar to felt emotion (Baumeister et al. 2007), Kramer et al. (2011) demonstrated that people are more likely to choose compromise and safe options when experiencing schadenfreude, as the emotion heightens anticipation of unfavorable outcomes. While these are important findings, they focus solely on the individual and not the social nature of the organization.

We argue that the real value in studying schadenfreude may lie in its effect on social learning at work. Emotions are not only felt privately; they may also be shared with others in social settings (Rimé 2009). When this occurs, emotions can communicate information about the values and beliefs of the individual expressing them (Van Kleef 2009). This is especially true in the case of moral emotions (Stearns and Parrott 2012), which raise awareness of acceptable versus unacceptable behaviors. Therefore, although schadenfreude has been painted as “a particularly insidious threat to social relations” (p. 932) because the experience of this positive emotion requires the suffering of another (Leach et al. 2003), we propose an alternative viewpoint. Based on the social functional account of emotion, we instead argue that the social sharing of schadenfreude at work can provide information to other employees about what constitutes ethical versus unethical behaviors.

One intended contribution of this research is to add to the nomological network surrounding schadenfreude by studying the social sharing of this emotion. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been any empirical research—in applied psychology or organizational behavior—that has examined the sharing of this emotion with others. This is important, because it is the social sharing of schadenfreude (as opposed to keeping it hidden inside oneself) through behaviors such as gossiping that can trigger the implications mentioned previously. As suggested by the emotions as social information model (EASI: Van Kleef 2009), it is the social sharing of this emotion that can prompt learning about ethical norms of behavior. We therefore focus on this aspect of schadenfreude in the first study described below.

Our second intended contribution is to examine the impact of target status on schadenfreude levels and the social sharing of this emotion. Despite Feather’s extensive work on the “tall poppy syndrome” (e.g., Feather 1989, 2008a), no advances have been made regarding the impact of target status on the intention to socially share this emotion with others. We therefore investigate differences in intended social sharing of schadenfreude when the target is labeled a CEO versus an employee in our second study.

We begin by exploring the definition of schadenfreude and its categorization as a moral emotion. We then examine the impact of perceived deservingness on schadenfreude and the willingness of individuals to share this socially undesirable emotion with fellow employees in Study 1. Building on these findings, we develop and test hypotheses regarding the influence of target status and the “tall poppy syndrome” on schadenfreude and sharing levels in Study 2.

Schadenfreude Defined

The word schadenfreude is unfamiliar to many who speak English despite its inclusion in some English dictionaries since the mid-1800s (Meier 2000). Perhaps the reason is because this word seems to be easily translated into English—the terms “gloating” and “malicious glee” are commonly used (Meier 2000). However, as Meier (2000) explains, these translations do not capture the exact meaning of the word. Further, despite being a positively valenced emotion, care must be taken not to oversimplify it (see Solomon 2003). Not all positive emotions feel good and have positive consequences (see also Lindebaum and Jordan 2012). A more nuanced examination is required for understanding in this case.

The context in which the word schadenfreude is used is very important to capture the meaning. For example, the context used by Szameitat et al. (2009) to study the expression of schadenfreude through laughter is a person slipping in dog droppings. Schadenfreude involves joy in response to this misfortune happening to the other person, but does not necessarily involve spite or a desire for serious harm to come to the person. Thus, schadenfreude should not be confused with sadism. The latter describes pleasure derived from the deliberate infliction of pain and suffering, whereas schadenfreude is derived from passive observation of another’s misfortune (Porter et al. 2014).

Leach et al. (2015) conducted a study examining differences between schadenfreude and other closely related positive emotions, such as gloating, pride, and joy. They demonstrated that schadenfreude is distinguishable from these emotions based on social appraisals, phenomenology, and action tendencies. Schadenfreude differs from pride, which results from achievement, and joy, which results from something pleasurable happening. It is more similar to gloating, which specifically results from triumph over or defeat of another person, as both involve joy at misfortune of another. However, schadenfreude does not necessarily require triumphing over the person who suffered the misfortune. In the case of schadenfreude, the others’ misfortune is not intentionally caused by the schadenfreudige person (the individual experiencing the schadenfreude: Leach et al. 2014). Leach et al. (2015) also found that schadenfreude was associated with lower levels of pleasure, celebration, and flaunting. Hence, gloating is more active and in direct opposition to the other party, whereas schadenfreude is simply a modest psychological boost to the self (Leach and Spears 2009).

Is Schadenfreude a Moral Emotion?

Before we go any further, it is important to address the categorization of schadenfreude as a moral emotion. Moral emotion is a matter of degree, and almost any emotion can meet criteria for being a moral emotion at least some of the time (Haidt, 2003). For this reason, when it comes to defining moral emotions and categorizing discrete emotions as being “moral,” there is still inconsistency in the scholarly literature. Over the last 100 years, around two-dozen discrete emotions have been labeled moral emotions (Rudolph et al. 2013; Rudolph and Tscharaktschiew 2014). These include shame, guilt, regret, embarrassment, contempt, anger, indignation, disgust, gratitude, envy, jealousy, scorn, admiration, sympathy, and schadenfreude (see Hareli and Parkinson 2008; Weiner, 2004). Yet, still there is no one clear agreed-upon list of moral versus non-moral emotions. This confusion should be of no surprise to emotion scholars, who have been disagreeing about the structure of emotional space for many years (e.g., dimensional vs. discrete models; Russell, 2003).

Some scholars (e.g., Haidt 2003) take a narrow view, defining moral emotions as only those that involve two criteria: disinterested elicitors (emotions triggered when the self has no stake in the event) and prosocial action tendencies. For this reason, research on moral emotions has traditionally focused primarily on guilt and sympathy (Haidt 2003). Haidt explains that while schadenfreude meets the first criteria, it “appears to involve no prosocial action tendency” (p. 864). He therefore labels schadenfreude as a marginal or non-prototypical moral emotion (Haidt 2003, p. 864). Despite this categorization, Haidt (2003) does state that schadenfreude contains an important moral component. Specifically, he notes that it is strongest when the person brought down was thought unworthy of his or her previous status (Portmann 2000).

Later work in the field has more solidly placed schadenfreude within the moral emotions category (Hareli and Parkinson 2008; Rudolph and Tscharaktschiew 2014; Weiner 2007). This categorization is largely based on the idea that moral emotions concern the welfare of others (Haidt 2003). Therefore, schadenfreude, being a response to others’ well-being, can be labeled a moral emotion as can its opposite, sympathy, which is also concerned with the needs of others (e.g., Eisenberg 2000; Gray and Wegner 2011; Hareli and Parkinson 2008). Weiner (2004) in particular firmly categorizes schadenfreude as a moral emotion. To classify moral emotions, Weiner argues that one needs to analyze antecedents of the emotion by considering what is good/bad, right/wrong, and ought/should (2006). Using this framework, he categorizes schadenfreude as a moral emotion because it is linked to appraisals of “ought” and “should,” and to controllable versus uncontrollable causes. Specifically, his categorization of moral emotions is based on idea that the “proper” or “moral” emotional reaction to failure (or misfortune) “ought to be” prosocial (p. 18). Next, we examine how schadenfreude might fit this prosocial criterion.

Schadenfreude Signals Normative Behaviors: A Social Functionalist Account

Given that schadenfreude is a socially undesirable emotion and may be perceived negatively by others (McNamee 2003, 2007), it raises a question: why would someone share this feeling? Even children as young as 4 years old have been shown to hide their feelings of schadenfreude as they are aware that it is a hurtful emotion (Schulz et al. 2013).

To address the question of why schadenfreude may be shared with others, we now turn to the social functionalist account of emotions. This perspective focuses on the adaptive role emotions play in social relationships between individuals, groups, and cultures (Ekman 1992; Keltner and Haidt 1999; Keltner et al. 2006). It suggests that emotions are a means of coordinating social interactions and maintaining relationships (Keltner and Haidt 1999). Emotions that are shared serve to communicate information about feelings, beliefs, and intentions. Emotions thus play a role in social learning (Tronick 1989; Van Kleef 2009), serving as deterrents (or incentives) for other individuals’ social behavior (Klinnert et al. 1983). Keltner and Haidt (1999) further explain that emotions define boundaries and help people learn the norms and values of their culture.

Applying the social functionalist approach, moral emotions represent positive or negative signals regarding behaviors (Walker and Jackson 2016). For example, gratitude feels good and thus sends a positive signal to do something again, while guilt feels bad and sends a negative signal to not do it again (Rudolph and Tscharaktschiew 2014). Schadenfreude is a discordant moral emotion, where the hedonic and functional qualities are of opposite valence. Rudolph and Tscharaktschiew (2014) explain that while schadenfreude is joyful (positive) it sends a negative signal to the observed person (e.g., you do not deserve help). In a social setting, this emotion can indicate what behaviors to avoid (to prevent schadenfreude from others), and encourage individuals to stay within particular boundaries.

Socially Sharing Schadenfreude

The signals from moral emotions may be sent to the person who is feeling the emotion as well as to others who observed the emotional response (including the target of the emotion) or were told about it later. As explained by Rimé (2009), the social sharing of emotions can take place minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, or years after an emotional episode. He explains that the social sharing of emotion occurs when individuals communicate openly about the emotion-eliciting event and about their own affective reactions to the event. It involves discourse between individuals, and these individuals are often intimately connected in some way; for example, family members, friends, and close work colleagues (Rimé 2009). Because thinking about and discussing a past positive emotional experience elicits pleasurable feelings in the present, people are motivated to ruminate on positive events they have experienced (see Horowitz 1969, 1975; Horowitz and Becker 1971, 1973 for example). This phenomenon is also referred to as ‘savoring’ (Bryant 1989). Thus, on an intrapersonal level, the social sharing of emotion benefits the individual who verbally shares emotional experiences with others (see Langston 1994).

The sharing of positive emotions can also enhance social bonds (Rimé 2009). When an individual verbally shares their positive emotions, it creates a situation in which others can display a willingness to support the communicator’s aspirations, goals, and values (Reis 2007). In the case of a positive response, this validation helps build the strength of relationships and enhances intimacy (Sullivan 1953). When this occurs, Gable and Reis (2010) theorized that individuals become more satisfied and committed to relationships due to the enthusiastic and supportive response received. However, it is also possible that the other individual may respond negatively to the communication. As Gable and Reis (2010) explained, if the sharing of the emotion is met with non-supportive behavior, or disengagement from the other individual, emotional distance is created and the relationship may deteriorate.

Given that the relational consequences of sharing emotions depend on the response received, it is sometimes risky for individuals to engage in this activity. We argue that this is especially true in the case of verbally sharing feelings of schadenfreude, which is often regarded as socially undesirable (McNamee, 2007). The risk may be exacerbated in workplace settings where the target of schadenfreude may be an individual with hierarchical power over employees experiencing and sharing the emotion. Rimé (2009) explained that individuals generally seek to protect themselves from the possibility of evoking harmful emotions in audiences. We believe that in the case of sharing schadenfreude, there is greater chance of this occurring as the source of the emotion is a misfortune impacting another person. Pennebaker and Harber (1993) discussed the fact that perceived receptiveness of the audience can discourage the likelihood of sharing emotions with others, and labeled this as “social constraint.”

Despite the risks inherent in sharing schadenfreude, we often read about others’ schadenfreude in the popular press (Kramer et al. 2011). For example, the joy of a competitor being booted from a reality TV show like “The Apprentice” (“You’re fired!”), or the arrest of controversial CEO Martin Shkreli (criticized for heavily raising the price of a prescription drug). Similar to the argument by Rimé (2009) regarding an example of sharing of emotions following a car accident, people who experience an emotion (even a socially undesirable one) often have “an imperious need to share it and to talk about it” (p. 65). In the case of schadenfreude, we argue that in some contexts there are possible benefits to be gained from doing so.

Deservingness and Sharing Schadenfreude

Ortony et al. (1988) suggested that “fortune-of-others” emotions are dependent on the perceived deservingness of the individual experiencing an outcome, especially in the case of feeling pleasure at the misfortune of others. Much of the scholarly research on schadenfreude has been put forth by Feather and colleagues, based on what Feather refers to as deservingness theory. Deservingness theory is based on the idea that observers feel greater pleasure in response to others’ failures when they believe that the target individual deserved the outcome and/or did not deserve the success they had achieved prior to the failure. Several studies (e.g., Feather 2008a; b; Feather and Nairn 2005; Feather et al. 2011; Feather and Sherman 2002) have supported this notion by linking the perceived deservingness of negative outcomes with schadenfreude.

Deservingness is considered to be a justice variable (Feather and Boeckmann 2007). If considering schadenfreude as pleasure resulting from justice being done, Portmann (2000) argues that this attests to the rationality of this emotion and to the responsibility of the person feeling it. Portmann (2000) explains that the pleasure stems from “hope that someone will learn a valuable lesson in having suffered” (p. 48), or “hope that he or she will correct a mistake” (p. 156). An interesting aspect of these findings was that the same regions of the brain were activated even when the punishment was administered at a personal cost. Despite the risk involved, individuals felt positive emotion due to the anticipation of the satisfying personal outcome.

Judgments of deservingness are determined by the degree to which an individual’s actions are deemed to be responsible for a positive or negative outcome (Feather 2006). Similarly, van Dijk et al. (2005) argued that schadenfreude is felt more strongly when observers perceive that victims are responsible for their negative outcomes (see also van Dijk et al. 2008). Hareli and Weiner (2002) utilized an attributional perspective to suggest that observers who attribute an individual’s success to illegitimate causes such as cheating will experience schadenfreude when that individual is caught or fails at a future task. Similarly, if a person’s failure at a task is attributed to insufficient effort, the authors argued that observers are likely to take some degree of pleasure in witnessing the failure as opposed to feeling sympathy.

While the relationship between perceived deservingness and schadenfreude is already well established in the social psychology literature by Feather and his colleagues (see Leach et al. 2014), there have not been any studies to examine how deservingness impacts the social sharing of this emotion with others. Based on the social functional account of emotion, we argue that perceived deservingness will not only be related to schadenfreude, but will also be related to the sharing of this emotion with others later. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

The perceived deservingness of misfortune is positively associated with intentions to socially share schadenfreude.

Hypothesis 2

Feelings of schadenfreude mediate the relationship between deservingness and intentions to socially share this emotion.

General Method Overview

The amount of schadenfreude one feels typically varies according to the severity of the misfortune or suffering of the other person. For this reason, it is important to have the same kind of misfortune befalling the individual that is the target of the schadenfreude in both the studies presented here. The misfortune in both studies was therefore held constant.

Earlier studies involving organizational phenomena focused on deservingness as an antecedent to schadenfreude within the context of a job application being rejected (Feather et al. 2011) and a promotion decision (Feather 2008b). We extend this work by focusing on a more morally intense misfortune—an individual’s employment being terminated. This operationalization of misfortune was chosen because another individual’s termination is likely sufficient in terms of magnitude to elicit feelings of schadenfreude (see Lee 2008).

In order to create a range of perceived deservingness scores, we manipulated deservingness levels using scenarios depicting varying levels of responsibility for a workplace misfortune, similar to van Dijk et al. (2005). By assigning subjects to different scenarios, we aimed to develop a sample containing a continuum of deservingness perceptions ranging from low to high. The deservingness distributions are described along with the results for Study 1 and Study 2 below.

Pre-test

To produce three scenarios that provided adequate manipulation of perceived deservingness, six pilot scenarios were developed and pre-tested using a separate sample of 160 undergraduate students. To promote realism, all six pilot scenarios were based on factual events reported in news articles in which CEOs had been terminated from their positions. These scenarios were from foreign countries to increase the likelihood that participants (all U.S. residents) would not be familiar with or biased toward the individual CEO or the organization the CEO was associated with. For the pilot test, two scenarios were selected to reflect each of the three levels of deservingness (i.e., high, medium, and low).

We used ANOVA-based manipulation checks to identify the three scenarios that produced the most pronounced statistically significant variation in participants’ perceptions of the CEOs’ deservingness (F(2,159) = 42.91, p < .01; see means and descriptions in Table 1). Deservingness was measured using five items (α = .90) adapted from Woolfolk et al. (2006). More information about this measure appears in the next section. The mean deservingness differences between the three retained scenarios were significant at p < .05 (low vs. medium) or p < .01 (low vs. high, medium vs. high).

Study 1

In Study 1, we used a between-subjects design to test the hypothesized relationships between deservingness, schadenfreude, and intentions to socially share this emotion with others (i.e., Hypotheses 1 and 2).

Sample

The sample consisted of 73 undergraduate students (63.0 % male, aged between 19 and 23 years) randomly assigned to one of the three deservingness prompts. 25 individuals were assigned to the low deservingness scenario, 26 to the medium deservingness scenario, and 22 to the high deservingness scenario.

Measures

Schadenfreude

We used van Dijk et al.’s (2005) five-item measure of schadenfreude (α = .86). A sample item was “I am happy with this outcome.” Participants were given the instructions to respond to each item specifically in response to the individual’s misfortune they read about in the scenario.

Social Sharing with Others

To measure the behavioral outcome of sharing schadenfreude (α = .79), five items were adapted from Zeithaml et al. (1996). These items were originally developed to measure negative word-of-mouth in the consumer behavior literature and have since been used to assess “trash talk” (Hickman and Ward 2007), which represents negative communication about a rival brand provoked not by specific unsatisfactory experiences with the brand (like negative word-of-mouth), but instead provoked by a sense of inter-group rivalry. Hickman and Ward (2007) explain that trash talk is associated with feelings of schadenfreude. Sample items from our study are “What is the likelihood that you would enjoy gossiping about this person’s termination to your friends?” and “What is the likelihood that you would tell others you enjoyed learning of the person’s termination?”

Perceived Deservingness

Perceived deservingness was measured utilizing the five items (α = .92) adapted from Woolfolk et al. (2006) used in the aforementioned pre-test. Responses were scored on a seven-point scale (1 = “Strongly disagree,” 7 = “Strongly agree”). An example item is “What happened to this person was deserved.”

Controls

We included gender as a control variable because all of the CEOs in the scenarios were male. Thus, gender was controlled to protect against potential gender biases (e.g., Samnani et al. 2014; Stylianou et al. 2013).

Results

Distribution of Perceived Deservingness Scores

The overall mean for perceived deservingness was 3.75 with a slightly left-skewed distribution (Kolmogrov–Smirnov statistic = .17, standard deviation = 1.75, skewness = −.13). An ANOVA test of the three deservingness conditions (F(2,70) = 18.99, p < .01) indicated that the mean differences between each response set (high = 5.61, medium = 3.68, low = 3.32) were all significant at the p < .05 level.

Hypothesis tests

Means, standard deviations, and correlations are shown in Table 2. To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, we utilized the MEDIATE procedure developed by Hayes and Preacher (2014). This procedure facilitates the calculation of bootstrapped confidence intervals as recommended in mediation tests given the non-normal distribution of indirect effects typically observed in all but very large samples (Edwards and Lambert 2007; Preacher and Hayes 2008). Results, shown in Table 3, indicated that perceived deservingness was associated with both schadenfreude (β = .39, p < .01) and sharing (β = .14, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 1. An examination of bootstrapped confidence intervals for the indirect effect of perceived deservingness through schadenfreude (.16) suggested a significant mediation effect (95 % confidence intervals: .06–.25), as predicted in Hypothesis 2. Gender impacted schadenfreude sharing scores (β = .45, p < .01) but not schadenfreude.

These findings provide an extension to schadenfreude’s nomological network by examining a predictor and an outcome of the emotion: deservingness and social sharing, respectively. This extension raises an important workplace question, however: would people differ in their willingness to socially share this emotion depending on whether the individual suffering the misfortune is a high status individual, such as an executive manager, versus a lower status individual, such as a lower-level peer or subordinate? The following study examines this question about the impact of status on schadenfreude and the social sharing of this emotion.

The Impact of Social Status on Schadenfreude and Sharing: The Tall Poppy Syndrome

Feather and colleagues have conducted a number of studies on the tall poppy syndrome in relation to feelings of schadenfreude (e.g., Feather 1989, 2008a; Feather et al. 1991). Tall poppies are defined as individuals who are successful and whose distinction, high rank, or wealth may attract hostility and/or feelings of envy (Feather 1989). Schadenfreude is argued to be a soothing response to these feelings (e.g., Leach et al. 2003; Smith et al. 1996; van Dijk et al. 2006) and studies suggest that observers tend to feel more schadenfreude when tall poppies suffer a misfortune as compared to an average person (Feather, 1989, 2008a, b).

Feather’s work on tall poppy syndrome also suggests that people enjoy the downfall of others who are in positions of high status due to resentment. Feather and Sherman (2002) demonstrated that resentment mediated the relationship between perceived deservingness of a person’s success and the likelihood that the observer would attempt to “cut down” the successful other—a response likely to promote schadenfreude. The authors also argued, and observed, that resentment would directly influence levels of schadenfreude, such that observers would experience positive affect when the undeserving other fails, even if the observers themselves did not cause the failure to occur. While this syndrome is part of the Australian culture (Feather and Boeckmann 2007), we also see similar effects in the US and other Western cultures. As reported in the Wall Street Journal (Zweig 2009), social standing influences how much schadenfreude people feel following a downfall, which may explain the amount of attention given to the downfall of rich and famous individuals in tabloid magazines.

Existing social psychology research on schadenfreude has frequently examined the presence of the emotion in competitive situations, such as among students who compare themselves to high-achievers (Feather 2008a; Leach and Spears 2008). Research has also looked at schadenfreude as a group-level emotion. Specifically, Leach et al. (2003) found that perceived inferiority to an out-group was associated with positive emotions following the failure of the out-group that was perceived to be superior. In their study, Leach et al. examined the reactions of European football teams’ fans and observed that schadenfreude was stronger among fans of inferior teams that beat superior teams than it was among fans of superior teams that were victorious over inferior teams. The theoretical perspectives used to study these situations and the associated findings suggest that many of the same competitive dynamics that give rise to schadenfreude toward tall poppies in these situations are also present in organizational scenarios.

Despite the advances in this domain, none of these studies examine whether status influences whether the emotion of schadenfreude is shared socially with others. Thus, we build on Feather’s foundational contributions (e.g., Feather 1989, 2003) by adding the social sharing of schadenfreude to the tall poppy literature. It is one thing to feel schadenfreude toward a higher status target, but sharing this emotion later with others is more risky if the person is indeed of higher status. Yet, it may also be more enjoyable for the person experiencing and then sharing it with others. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Target status interacts with deservingness, such that for a given level of perceived deservingness higher status targets will evoke higher levels of (a) schadenfreude and (b) social sharing of schadenfreude.

Hypothesis 4

The interactive effect of deservingness and status on the social sharing of schadenfreude is mediated by schadenfreude.

Study 2

The aim of this study is to examine the impact of status on feelings of schadenfreude and the sharing of this emotion with others (Hypotheses 3–4). Hence, we use a between-subjects design with 2 levels of status (employee, leader). The same scenarios from Study 1 were used with the target individual being labeled as “CEO” in the scenarios given to approximately half of the subjects and “employee” in the other half. All other information presented in the scenarios remained constant with the Study 1 wording regarding the nature of the misfortune.

Sample

Two hundred and twenty-two undergraduate students participated in Study 2 (58.6 % male, aged between 18 and 40 years). 74 subjects were assigned to each of the three deservingness prompts: 108 to the employee scenarios and 114 to the leader scenarios.

Measures

Perceived deservingness (α = .83), schadenfreude (α = .86), and social sharing (α = .76) were measured using the same scales described in Study 1. Due to the significant finding in Study 1, gender was again included as a control variable. Given the wider variance in subjects’ ages in this sample relative to Study 1, age was also controlled.

Results

Distribution of Perceived Deservingness Scores

The overall mean for perceived deservingness was 4.25. As with Study 1, the distribution of scores was slightly left-skewed (Kolmogrov–Smirnov statistic = .14, standard deviation = 1.53, skewness = −.18). An ANOVA test of the three deservingness conditions (F(2,219) = 66.19, p < .01) indicated that the mean differences between each condition (high = 5.49, medium = 3.98, low = 3.24) were significant at the p < .05 level.

Hypothesis tests

Means, standard deviations, and correlations are shown in Table 4.

Taken together, Hypotheses 3 and 4 suggest a moderated mediation relationship in which participants are expected to report stronger schadenfreude and, in turn, social sharing when a higher status target is terminated than when a lower status target is terminated for the same reason. Hayes’ (2015) PROCESS analysis was employed to examine these relationships, utilizing the model template #8 in order to test the impact of the status × deservingness interaction on both schadenfreude and sharing simultaneously.

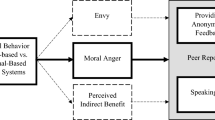

Results, shown in Table 5, indicate that perceived deservingness and status interacted to influence schadenfreude sharing (β = −.14, p < .05) but not the emotion itself. As such, Hypothesis 3a was not supported. As shown in Fig. 1, when perceived deservingness was relatively low, respondents indicated a stronger willingness to share schadenfreude about organizational leaders (CEOs) than lower status employees. At higher levels of perceived deservingness, schadenfreude sharing scores were nearly identical regardless of whether wrongdoers were leaders or employees. This suggests partial support for Hypothesis 3b, in that wrongdoer status influenced schadenfreude sharing scores at lower levels of perceived deservingness. As the perceived severity of wrongdoing increased, however, the importance of status appeared to diminish.

The conditional direct effects of perceived deservingness on schadenfreude sharing at high and low levels of status shown in Table 5 tell a similar story. The effect of perceived deservingness on sharing was stronger for low status employees (effect = .30, 95 % CI: .21–.40) than for high status employees (effect = .17, 95 % CI: .07–.26). This is reflected in the steeper slope of the employee status line in Fig. 1 and again suggests that the effect of status diminished as the perceived deservingness of a wrongdoer increased.

Hypothesis 4 predicted that schadenfreude would mediate the impact of perceived deservingness and wrongdoer status on schadenfreude sharing. Although status did not influence the impact of perceived deservingness on schadenfreude, Table 5 shows that these feelings mediated the impact of deservingness on schadenfreude sharing at both high (CEO effect = .09, 95 % CI: .04–.15) and low (employee effect = .11, 95 % CI: .07–.17) status levels. The effect sizes at both levels do not differ significantly (index of moderated mediation = .025, 95 % CI: −.08 to .03; Hayes 2015), again reflecting the lack of impact that status had on schadenfreude relative to perceived deservingness. Thus, while schadenfreude mediated the impact of perceived deservingness on the social sharing of schadenfreude, status did not appear to influence the levels these feelings in the same manner that it influenced the decision to share them with others, as described above.

General Discussion

As suggested by Treviño et al. (2006), research into discrete emotions is required to better understand organizational ethics and what is considered to be moral behavior at work. The purpose of our studies was to understand more about the discrete emotion of schadenfreude and the social sharing of this moral emotion. In two experiments, empirical support was found for the notion that schadenfreude, and the desire to share these feelings, increased in step with the perceived deservingness of a wrongdoer’s misfortune. These findings mirror the earlier work by Feather (1992, 2006, 2008a, b), who established the role of perceived deservingness in relation to feeling schadenfreude. When investigating the influence of the tall poppy syndrome, in which higher status individuals are thought to be targets of more schadenfreude than lower status individuals, a slightly more complicated picture emerged.

Consistent with Feather’s (1989, 1992) arguments, we found that misfortunes befalling wrongdoers in leadership positions invoked a stronger desire to share schadenfreude among respondents. However, this occurred only when the severity of the wrongdoing was relatively minor and perceived deservingness was low. The status effect seemed to disappear when wrongdoers were terminated for more severe acts of misconduct. Thus, although we found some evidence of the tall poppy effect in terms of schadenfreude sharing, it seemed to dissipate beyond a certain level of perceived wrongdoing. Perpetrators of especially severe ethical misconduct may be seen as “fair game” regardless of their status.

Interpreting this finding through a social functional lens (Keltner and Haidt 1999), we argue that sharing schadenfreude felt toward an unethical other has social benefits, regardless of who the unethical other is. In this context, sharing schadenfreude communicates information with others about ethical norms of behavior, what is considered to be “right” and “wrong.” In the same way that moral emotions such as anger can serve a signaling function by communicating negative feedback (Walker and Jackson 2016), schadenfreude can provide social information to others that is highly valuable in a workplace setting (Van Kleef 2009). More specifically, it can send a negative signal to others about engaging in unethical behavior. Given the value of such information, the status of the schadenfreude target may take on diminished importance for the individual sharing it in cases of severe misconduct.

Contributions and Suggestions for Future Research

While we believe that the examination of schadenfreude in a workplace context is informative, we also sought to add to the scholarly literature by introducing a new outcome variable in relation to schadenfreude: the social sharing of this emotion with others. To our knowledge, this is the first research to empirically demonstrate the mediation effect from deservingness through schadenfreude to the intention of sharing the emotion with others.

Discrete emotions, and moral emotions in particular, communicate rich information when they are shared. We argue that sharing schadenfreude with others can prompt social learning about ethical norms of behavior, as suggested by the social functional account of emotion (Keltner and Haidt 1999) and the EASI model (Van Kleef 2009). In the case of schadenfreude, individuals can learn which behaviors to avoid in order to prevent becoming future targets of schadenfreude themselves. Hence, the discrete emotion of schadenfreude serves social functional needs when it is shared within the context of misfortune following unethical behaviors. We propose that within other contexts that do not involve ethical issues prior to a misfortune, there is no such social functional benefit from sharing this emotion with others.

We bring a new spin to the research on this process by examining the sharing of positive emotions in relation to a negative event (the misfortune of another individual). This is a unique approach and we believe that it warrants further attention. Lindebaum and Jordan (2012) argued against simplistic associations in the study of workplace emotions, such as positive events evoking positive emotions which then have positive outcomes. We attend to their call for examining more complicated asymmetrical effects and taking into account the context in which the emotions are occurring.

Although we assessed intention to socially share this emotion, learning about the actual verbal sharing of this emotion would be highly beneficial for our understanding of the implications of schadenfreude. As Rimé (2009) explained, not all emotional episodes are shared. For example, individuals may refrain from sharing positive emotions with others if they are associated with shame, fear, or guilt (e.g., a guilty pleasure). In the case of feeling schadenfreude, since this is a socially undesirable emotion, individuals may feel self-conscious and this may prevent them from sharing their schadenfreude socially with others. Future research can illuminate the relationship between the feeling of, and sharing, socially undesirable emotions by examining specific contextual inducements/restraints, such as leadership styles, organizational climate, and the cohesiveness of work teams in which emotions are shared (see Dasborough et al. 2009; Cropanzano and Dasborough 2015).

Future research could also investigate the relationship between schadenfreude and other discrete workplace emotions. Anticipated schadenfreude and workplace frustration might interact to promote workplace sabotage, for example. Frustration often stems from perceived injustice, such as when employees feel that they are being mistreated relative to other employees, and has been shown to motivate sabotage aimed at “even[ing] the score” (Ambrose et al. 2002, p. 950). Our arguments and existing research on anticipatory emotions (e.g., Baumeister et al. 2007; Harvey and Victoravich 2009) suggest that anticipated schadenfreude might also motivate such acts of sabotage if employees expect that the experience and social sharing of schadenfreude will serve to channel the negative emotion of frustration into a more pleasurable affective state.

Strengths and Limitations of the Research

As with all research designs, there are inherent strengths and limitations in these two studies. Scenario studies, using some imagination on the part of the participant, have frequently been used to study schadenfreude (e.g., Feather et al. 2011; Takahashi et al. 2009). While external validity may be questioned, this approach enhances internal validity. The use of scenarios, with fictitious individuals being terminated, allows us to control for other sources of schadenfreude that may be present in a real workplace setting. For example, research has noted the impact of resentment and envy on schadenfreude (Feather and Sherman 2002). Using actual employees could invoke such social emotions. For example, an employee may be envious of a coworker’s performance on the job, compensation, his/her family, social life, etc. Field studies might therefore be contaminated by these other influences.

The study of schadenfreude in actual workplaces is challenging due to the temporal and subjective nature of social interactions and the emotion display rules that exist in workplaces. As Mook (1983) explained, laboratory designs are more appropriate than field designs when the lab can be used to create conditions that have no counterpart in real life. Given the socially undesirable nature of schadenfreude, the potential consequences of it being publically known in a workplace environment, and the complexity of working relationships with histories, a laboratory setting is useful to demonstrate schadenfreude and the intent to share it with others. It could be difficult to study this phenomenon, especially in regards to the tall poppy syndrome, in a workplace setting without employee fear of reprisal.

We also caution that the content in the three real-life scenarios could potentially have confounded the results. There may have been something about the organization type or in the description of the CEOs and employees that evoked a particular response in the subjects across the conditions. Similar to all scholars designing experiments, we had to balance our need for external realism with internal validity concerns (Mook 1983). Future research could address this concern by using a single scenario and only adjusting the reason for termination within that same scenario. This would reduce the possible impact of using different organizations and different CEO’s to manipulate levels of deservingness.

While one could question the emotions reported in response to a hypothetical scenario, Robinson and Clore (2001) argue that there is consistency between findings in studies using hypothetical scenarios and those that are based on actual emotional experiences. Further, the magnitude of affective reactions would have been attenuated by the design reducing, rather than increasing, the likelihood of finding support for the hypothesized relationships. In a field sample, individuals may report stronger schadenfreude and would more likely share these strong feelings with their closest friends at work. We recommend future research in the field which would enable us to examine other relevant variables (e.g., relationship history, current relationship quality, level of interaction, the impact of emotional labor requirements, and the specific context of the misfortune befalling the schadenfreude target) which we believe would provide even stronger results than the ones presented here. We also acknowledge that individuals are likely to experience more than one emotion in response to work events, and other discrete emotions, such as sympathy and anger, should be examined in conjunction with schadenfreude to uncover the true complexity of moral emotional life.

Our samples for each of the experimental studies also present a potential limitation, as participants were relatively homogeneous (undergraduate students of similar ethnicity). The effect of this is potential decreased within-cell variance in the studies utilizing manipulations. Despite this, we did find enough variance between individuals to produce interesting results. Recently, Falk et al. (2013) examined the use of student samples to see if they misrepresent social preferences. They found that student participants and non-student participants show very similar patterns of behavior. Given the specific phenomenon under investigation (i.e., an emotional response to a stimulus), and since research on socially sharing schadenfreude is still in its infancy, the use of a laboratory setting with student samples is not of concern (see Mook 1983). We argue that this methodology may be more appropriate than a field survey at this early stage. Of course, we would suggest that this work is later followed by field studies with employee samples, as discussed previously.

Practical Implications

Our findings point to the fact that schadenfreude, despite its negative connotations, is likely to be socially shared with others following the deserved misfortune of an unethical other, regardless of their status. “Deserved misfortunes” are associated with attributions of control and unethical behavior, not misfortunes caused by happenstance or bad luck (see Rudolph and Tscharaktschiew 2014; Weiner 2004). Therefore, when employees feel schadenfreude in response to a deserved misfortune befalling an unethical coworker and share this emotion with others, they could be helping build an ethical climate through signaling inappropriate behaviors to others. We propose that socially sharing schadenfreude with others does not serve a functional purpose unless it is communicating valuable information, such as what is ethical and what is not. Within the particular context of feeling schadenfreude toward unethical others, valuable information can be learned from the social sharing of this discrete emotion.

We are not suggesting that organizations should promote schadenfreude, but instead we believe they should encourage a range of emotions in response to ethical/unethical workplace behaviors, including pride in response to ethical behavior, guilt in response to own unethical deeds, and perhaps moderate levels of schadenfreude in response to the consequences of unethical behavior by others. Moral emotions are signals that should not be ignored (Hareli et al. 2013; Walker and Jackson 2016), and they can provide information about what is deemed to be an ethical behavior in workplaces.

Since emotions are often shared with close others, they are likely to have implications for the ongoing relationships between individuals (Gable and Reis 2010). The social sharing of schadenfreude can have positive implications for the relationships if the feelings are mutual (see also Cropanzano et al. 2017, in press). Further, relationships may also be enhanced if the sharing of schadenfreude involves humor. As Portmann (2000) explained, people may share their schadenfreude with the intention to be humorous, in order to build working relationships through comedy, rather than damaging them. While we present a positive side of schadenfreude, in regards to the social function it performs within the context of prior unethical behavior, we must also acknowledge the negative side too. Privately feeling schadenfreude may be relatively harmless. Yet, we note that schadenfreude is an antisocial emotion, which then shared with others, can erode working relationships if individuals do not share the same sentiments, do not see it as humorous, and if the resulting negative emotions spread through the organization via emotional contagion (see Dasborough et al. 2009).

Given our findings in relation to the tall poppy syndrome, our results also have practical implications for leaders. The scenario studies here demonstrate that individuals are more likely to act on schadenfreude if the target of the misfortune is a leader. While much of this response is out of the leader’s control, we propose that leaders should try to avoid appearing smug, self-satisfied, or entitled (Harvey and Dasborough 2015; Kirwan-Taylor 2006), which may heighten later schadenfreude responses. Emotional intelligence would help leaders manage their emotional displays and anticipate the emotions of their followers (see Antonakis et al. 2009).

Closing Remarks

To conclude, we challenge the view that schadenfreude is an emotion that has negative implications for workplace relationships. Instead, we dare to know (Holt and den Hond 2013) more about the possible positive effects of this underexplored “distasteful” emotion. As Lindebaum and Jordan (2012) explain, we need to look beyond emotion valence and symmetrical effects on workplace outcomes. Our research contributes to the expanding literature on organizational emotions by providing an initial exploration into the social sharing of this moral emotion. Socially sharing schadenfreude signals to other individuals in the organization ethical behavioral norms. The social functional account of emotions tells us that moral emotions provide stop and start signals (Rudolph and Tscharaktschiew 2014). Socially sharing the moral emotion of schadenfreude is especially fascinating, as not only can it send a signal to the target, but also to others, about what is morally correct behavior in a particular workplace setting. It serves the function of highlighting what behaviors to avoid. Historian Peter Gay argued that schadenfreude is one of the great joys of life (Rothstein 2000). We agree that schadenfreude is indeed pleasurable, but suggest that it can be socially functional as well.

References

Ambrose, M. L., Seabright, M. A., & Schminke, M. (2002). Sabotage in the workplace: The role of organizational injustice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 947–965.

Antonakis, J., Ashkanasy, N. M., & Dasborough, M. T. (2009). Does leadership need emotional intelligence? The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 247–261.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Dewall, C. N., & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 167–203.

Brigham, N. L., Kelso, K. A., Jackson, M. A., & Smith, R. H. (1997). The roles of invidious comparisons and deservingness in sympathy and Schadenfreude. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 19(3), 363–380.

Bryant, F. B. (1989). A four factor model of perceived control: Avoiding, coping, obtaining, and savoring. Journal of Personality, 57, 773–797.

Cropanzano, R., & Dasborough, M. T. (2015). Dynamic models of well-being: Implications for individual personality and affective climates. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 844–847.

Cropanzano, R., Dasborough, M. T., & Weiss, H. (2017). Affective events and the development of leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Review (in press).

Dasborough, M. T., Ashkanasy, N. M., Tee, E. Y. J., & Tse, H. H. M. (2009). What goes around comes around: How meso-level negative emotional contagion can ultimately determine organizational attitudes toward leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 571–585.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22.

Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 51, 665–697.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3–4), 169–200.

Falk, A., Meier, S., & Zehnder, C. (2013). Do lab experiments misrepresent social preferences? The case of self-selected student samples. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11, 839–852.

Feather, N. T. (1989). Attitudes towards high achievers: The fall of the tall poppy. Australian Journal of Psychology, 41, 239–267.

Feather, N. T. (1992). An attributional and value analysis of deservingness in success and failure situations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 125–145.

Feather, N. T. (2003). Tall poppies and schadenfreude. Australian Journal of Psychology, 55, 41–42.

Feather, N. T. (2006). Deservingness and emotions: Applying the structural model of deservingness to the analysis of affective reactions to outcomes. European Review of Social Psychology, 17, 38–73.

Feather, N. T. (2008a). Effects of observer’s own status on reactions to a high achiever’s failure: Deservingness, resentment, schadenfreude, and sympathy. Australian Journal of Psychology, 60(1), 31–43.

Feather, N. T. (2008b). Perceived legitimacy of a promotion decision in relation to deservingness, entitlement, and resentment in the context of affirmative action and performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(5), 1230–1254.

Feather, N. T., & Boeckmann, R. J. (2007). Beliefs about gender discrimination in the workplace in the context of affirmative action: Effects of gender and ambivalent attitudes in an Australian sample. Sex Roles, 57(1–2), 31–42.

Feather, N., McKee, I., & Bekker, N. (2011). Deservingness and emotions: Testing a structural model that relates discrete emotions to the perceived deservingness of positive or negative outcomes. Motivation and Emotion, 35(1), 1–13.

Feather, N. T., & Nairn, K. (2005). Resentment, envy, schadenfreude, and sympathy: Effects of own and other’s deserved or undeserved status. Australian Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 87–102.

Feather, N. T., & Sherman, R. (2002). Envy, resentment, schadenfreude, and sympathy: Reactions to deserved and undeserved achievement and subsequent failure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 953–961.

Feather, N. T., Volkmer, R. E., & McKee, I. R. (1991). Attitudes towards high achievers in public life: Attributions, deservingness, personality, and affect. Australian Journal of Psychology, 43, 85–91.

Gable, S. L., & Reis, H. T. (2010). Good news! Capitalizing on positive events in an interpersonal context. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 42, pp. 195–257). San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Dimensions of moral emotions. Emotion Review, 3, 258–260.

Greene, J. D. (2011). Emotion and morality: A tasting menu. Emotion Review, 3, 227–229.

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hareli, S., Moran-Amir, O., David, S., & Hess, U. (2013). Emotions as signals of normative conduct. Cognition and Emotion, 27, 1395–1404.

Hareli, S., & Parkinson, B. (2008). What’s social about social emotions? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 38(2), 131–156.

Hareli, S., & Weiner, B. (2002). Social emotions and personality inferences: A scaffold for a new direction in the study of achievement motivation. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 183–193.

Harvey, P., & Dasborough, M. T. (2015). Entitled to solutions: The need for research on workplace entitlement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(3), 460–465.

Harvey, P., & Victoravich, L. M. (2009). The influence of forward-looking antecedents, uncertainty and anticipatory emotions on project escalation. Decision Sciences Journal, 40, 759–782.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22.

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable, 67, 451–470.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Hickman, T., & Ward, J. (2007). The dark side of brand community: Inter-group stereotyping, trash talk, and schadenfreude. In G. J. Fitzsimons (Ed.), Advances in Consumer Research Vol Xxxiv (Vol. 34, pp. 314–319).

Holt, R., & den Hond, F. (2013). Sapere aude. Organization Studies, 34(11), 1587–1600.

Horberg, E. J., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2011). Emotions as moral amplifiers: An appraisal tendency approach to the influences of distinct emotions upon moral judgment. Emotion Review, 3, 237–244.

Horowitz, M. J. (1969). Psychic trauma: Return of images after a stress film. Archives of General Psychiatry, 20, 552–559.

Horowitz, M. J. (1975). Intrusive and repetitive thoughts after experimental stress: A summary. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32, 1457–1463.

Horowitz, M. J., & Becker, S. S. (1971). Cognitive response to stress and experimental demand. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 78, 86–92.

Horowitz, M. J., & Becker, S. S. (1973). Cognitive response to erotic and stressful films. Archives of General Psychiatry, 29, 81–84.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 13, 505–521.

Keltner, D., Haidt, J., & Shiota, M. N. (2006). Social functionalism and the evolution of emotions. Evolution and Social Psychology, 123, 115–142.

Kirwan-Taylor, H. (2006). Are you suffering from tall poppy syndrome? Management Today, 15.

Klinnert, M. D., Campos, J., Sorce, J. F., Emde, R. N., & Svejda, M. J. (1983). Social referencing: Emotional expressions as behavior regulators. Emotion: Theory Research and Experience, 2, 57–86.

Kramer, T., Yucel-Aybat, O., & Lau-Gesk, L. (2011). The effect of schadenfreude on choice of conventional versus unconventional options. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116, 140–147.

Langston, C. A. (1994). Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1112–1125.

Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2008). A vengefulness of the impotent: The pain of in-group inferiority and schadenfreude toward successful out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1383–1396.

Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2009). Dejection at in-group defeat and schadenfreude toward second-and third-party out-groups. Emotion, 9(5), 659–665.

Leach, C. W., Spears, R., Branscombe, N. R., & Doosje, B. (2003). Malicious pleasure: Schadenfreude at the suffering of another group. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 932–943.

Leach, C. W., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2014). About another’s misfortune: Situating schadenfreude in social relations. In W. W. van Dijk & J. W. Ouwerkerk (Eds.), Schadenfreude: Understanding pleasure at the misfortune of others (pp. 200–216). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leach, C. W., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2015). Parsing (malicious) pleasures: Schadenfreude and gloating at others’ adversity. Frontiers in Psychology, 6.

Lee, L. (2008). Schadenfreude, baby!: A delicious look at the misfortune of others (and the pleasure it brings us). Guilford: Globe Pequot.

Lindebaum, D., & Jordan, P. (2012). Positive emotions, negative emotions or utility of discrete emotions? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 1027–1030.

McNamee, M. (2003). Schadenfreude in sport: Envy, justice, and self-esteem. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 30(1), 1–16.

McNamee, M. (2007). Nursing schadenfreude: The culpability of emotional construction. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 10(3), 289–299.

Meier, A. J. (2000). The status of foreign words in English: The case of eight German words. American Speech, 75(2), 169–183.

Mook, D. G. (1983). In defense of external invalidity. American Psychologist, 38, 379–387.

Ortony, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (1988). The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parkinson, B., & Manstead, A. S. (2015). Current emotion research in Social Psychology: Thinking about emotions and other people. Emotion Review, 1754073915590624.

Pennebaker, J. W., & Harber, K. D. (1993). A social stage model of collective coping: The Loma Prieta earthquake and the Persian Gulf War. Journal of Social Issues, 49, 125–145.

Porter, S., Bhanwer, A., Woodworth, M., & Black, P. J. (2014). Soldiers of misfortune: An examination of the Dark Triad and the experience of schadenfreude. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 64–68.

Portmann, J. (2000). When bad things happen to other people. New York: Routledge.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Reis, H. T. (2007). Steps toward the ripening of relationship science. Personal Relationships, 14, 1–23.

Rime, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1, 60–85.

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2001). Simulation, scenarios, and emotional appraisal: Testing the convergence of real and imagined reactions to emotional stimuli. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1520–1532.

Rothstein, E. (2000). Missing the fun of a minor sin, New York Times, February 5.

Rudolph, U., Schulz, K., & Tscharaktschiew, N. (2013). Moral emotions: An analysis guided by Heider’s naive action analysis. International Journal of Advances in Psychology, 2(2), 69–92.

Rudolph, U., & Tscharaktschiew, N. (2014). An attributional analysis of moral emotions: Naïve scientists and everyday judges. Emotion Review, 6(4), 344–352.

Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110(1), 145–172.

Samnani, A., Salamon, S., & Singh, P. (2014). Negative affect and counterproductive workplace behavior: The moderating role of moral disengagement and gender. Journal of Business Ethics, 119, 235–244.

Schulz, K., Rudolph, A., Tscharaktschiew, N., & Rudolph, U. (2013). Daniel has fallen into a muddy puddle—Schadenfreude or sympathy? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31, 363–378.

Smith, R. H., Turner, T. J., Garonzik, R., Leach, C. W., Urch-Druskat, V., & Weston, C. M. (1996). Envy and schadenfreude. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(2), 158–168.

Solomon, R. (2003). Not passion's slave: Emotions and choice. Oxford University Press.

Stearns, D. C., & Parrott, W. (2012). When feeling bad makes you look good: Guilt, shame, and person perception. Cognition and Emotion, 26, 407–430.

Stylianou, A., Winter, S., Niu, Y., Giacalone, R., & Campbell, M. (2013). Understanding the behavioral intention to report unethical information technology practices: The role of Machiavellianism, gender and computer expertise. Journal of Business Ethics, 117, 333–343.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Szameitat, D. P., Alter, K., Szameitat, A. J., Wildgruber, D., Sterr, A., & Darwin, C. J. (2009). Acoustic profiles of distinct emotional expressions in laughter. Journal Acoustic Society America, 126, 354–366.

Takahashi, H., Kato, M., Matsuura, M., Mobbs, D., Suhara, T., & Okubo, Y. (2009). When your gain is my pain and your pain is my gain: Neural correlates of envy and schadenfreude. Science, 323(5916), 937–939.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Tronick, E. Z. (1989). Emotions and emotional communication in infants. American Psychologist, 44(2), 112.

van Dijk, W. W., Goslinga, S., & Ouwerkerk, J. W. (2008). Impact of responsibility for a misfortune on schadenfreude and sympathy: Further evidence. Journal of Social Psychology, 148(5), 631–636.

van Dijk, W. W., Ouwerkerk, J. W., Goslinga, S., & Nieweg, M. (2005). Deservingness and schadenfreude. Cognition and Emotion, 19(6), 933–939.

van Dijk, W. W., Ouwerkerk, J. W., Goslinga, S., Nieweg, M., & Gallucci, M. (2006). When people fall from grace: Reconsidering the role of envy in schadenfreude. Emotion, 6(1), 156–160.

Van Kleef, G. A. (2009). How emotions regulate social life the emotions as social information (EASI) model. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(3), 184–188.

Weiner, B. (2004). Social motivation and moral emotions. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Attribution theory: An organizational perspective (pp. 5–24). Delray Beach: St. Lucie Press.

Weiner, B. (2007). Examining emotional diversity in the classroom: An attribution theorist considers the moral emotions. In P. A. Schutz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 75–88). San Diego: Academic Press.

Wiesenfeld, B. M., Wurthmann, K. A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2008). The stigmatization and devaluation of elites associated with corporate failures: A process model. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 231–251.

Woolfolk, R. L., Doris, J. M., & Darley, J. M. (2006). Identification, situational constraint, and social cognition: Studies in the attribution of moral responsibility. Cognition, 100(2), 283–301.

Walker, B. R., & Jackson, C. J. (2016). Moral emotions and corporate psychopathy: A review. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3038-5.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46.

Zweig, J. (2009). Financial crisis has an upside: The joy of schadenfreude. (Wall Street Journal Blog). Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/wallet/2009/02/12/wall-street-crisis-schadenfreud/tab/article/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dasborough, M., Harvey, P. Schadenfreude: The (not so) Secret Joy of Another’s Misfortune. J Bus Ethics 141, 693–707 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3060-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3060-7