Abstract

Media increasingly accuse firms of exploiting suppliers, and these allegations often result in lurid headlines that threaten the reputations and therefore business successes of these firms. Neither has the phenomenon of supplier exploitation been investigated from a rigorous, ethical standpoint, nor have answers been provided regarding why some firms pursue exploitative approaches. By systemically contrasting economic liberalism and just prices as two divergent perspectives on supplier exploitation, we introduce a distinction of common business practice and unethical supplier exploitation. Since supplier exploitation is based on power, we elucidate several levels of power as antecedents and investigate the role of ethical climate as a moderator. This study extends Victor and Cullen’s (1988) ethical climate matrix according to a supply chain dimension and is summarized in an integrated, conceptual model of five propositions for future theory testing. Results provide a frame of reference for executives and scholars, who can now delineate unethical exploitation and understand important antecedents of the phenomenon better.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increase in stakeholder interest in corporate social responsibility and ethical issues (Maon et al. 2009) has resulted in a higher public awareness for multinational corporations accused of misusing power over suppliers. Headlines such as “Wilkinson Squeezes Suppliers” (Parsons 2009), “How Coles Squeezed Suppliers” (Greenblat 2014b) or “Boeing Will Squeeze Suppliers and Cut Jobs” (Gates, 2013) demonstrate how allegedly exploitive business practices of buying firms are being scrutinized. Other examples of exploitation can be found in the retail industry, including large discounters such as Tesco, Walmart, Carrefour and Aldi (Bloom and Perry 2001; Burritt et al. 2010; Kumar 2005; Ruddick and Roland 2015; Smith and Cripps 2009), and in industries shown in Table 1.

Perhaps the most famous example of abusive power is linked to José Ignacio López de Arriortúa, who threatened suppliers in the early 1990 s. When López became vice president of purchasing at General Motors, a new era of supplier exploitation began (Henke et al. 2009). General Motors not only demanded price concessions from suppliers for upcoming seasons, but also misused its market power to cancel and renegotiate existing contracts (Levin 1993; The Economist 1998). By revealing these practices of pressuring suppliers for price reductions, and non-cost related payments or discounts, extended payment terms, warranty periods and questionable appropriation of innovations and intellectual property (Emiliani 2003; Fearne et al. 2004), the media reported about extremely negative cases. However, to date, the topic of unethical buying behaviour in buyer–supplier dyads has been neglected in scholarly research despite several exceptions. Extant studies of supply chain management (SCM) highlight the importance of this broader field of ethics as they investigate, for example, causes of and solutions for unethical behaviour (Badenhorst 1994), inter-organizational determinants of unethical purchasing practices (Saini 2010) and unethical bargaining tactics (Olekalns and Smith 2009). Fassin (2005) argues that unfair supply chain practices—including fraud, misuse of power advantages to lower prices and favouring suppliers because of gifts—are omnipresent. Few studies (Bloom and Perry 2001; Henke et al. 2008, 2009) address what we consider supplier exploitation, and little has been said about the differentiation between ethical and unethical practices in buyer–supplier relationships. Apart from multiple anecdotal examples, it is unclear under which conditions superior buyer power is abused for unethical supplier exploitation.

This issue is insofar problematic since firms need to identify these issues as unethical to manage them. Supply chain and purchasing managers are usually incentivized to save as much money as possible with suppliers since profit maximization is a routine procedure in many firms. Following this logic, exploitation could be perceived as a common business practice,Footnote 1 and therefore ethical dilemmas could be ignored. Consequently, there is no criterion to distinguish the scope of unethical supplier exploitation simplistically in comparison to cases in which suppliers are not treated unethically. Whether one party takes advantage of another, or simply engages in common business practice, depends on the contextual parameters that play a role during these comparisons. Thus, there should be an urgent call for academic debate—both economically and ethically. To address this gap, we apply a critical approach to SCM that transcends purely economic reasons, offering conceptual consideration of unethical supplier exploitation that elucidates two aspects: (1) How can unethical supplier exploitation be defined? and (2) What antecedents lead to unethical supplier exploitation and which role does the ethical climate in a buying firm play?

To answer these questions, we draw from well-known but opposing theories related to the phenomenon since a single theory would fall short of explaining the complexity of exploitation. We anchor the analysis particularly on Aquinas’s (1920) concept of just prices, which we transfer to an SCM context. We contrast this moral viewpoint with an economic viewpoint, the classical liberal paradigm of transactions, to arrive at two definitions that sharpen the distinction between unethical exploitation and common business practice. While discovering reasons for unethical supplier exploitation, we focus on various aspects from power literature since power is a primary construct when it comes to exploitation generally. Since ethical climate is an important factor for implementation of unethical behaviour, we extend ethical climate literature and conceptualize its moderation on supplier exploitation.

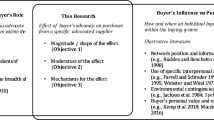

The contributions are threefold, lying at the intersection of SCM and business ethics, particularly literature concerning ethical climate. We introduce the term unethical supplier exploitation to both SCM and business ethics scholars and practitioners, and systemically explore its vague concept by providing two definitions of unethical supplier exploitation: a liberal and a fairness-oriented version. This distinction serves as a foundation for SCM decisions since it helps managers reflect on their approaches and make business relationships fairer and more ethical. We advocate the moral viewpoint, with its fairness-oriented definition of unethical supplier exploitation, as a criticism of the purely economic viewpoint. We propose a coherent, conceptual model of antecedents for unethical supplier exploitation, including direct effects and moderators that influence the propensity of buying firms to exploit suppliers unethically. With the identification of antecedents to supplier exploitation, we contribute to the fields of business ethics and SCM theoretically since these antecedents can be tested with future empirical research. They enrich SCM decision-making scenarios since practitioners might be in a better position to control the phenomenon and influence its emergence. We contribute to the ethical climate theory by extending Victor and Cullen’s (1988) theoretical matrix of ethical climates and introducing a new supply chain dimension. When Victor and Cullen (1988) developed the theoretical matrix of ethical climates, purchasing as the upstream and supply perspective of SCM was a tactical rather than strategic function (Carter and Narasimhan 1996), and certainly had much less influence and fewer responsibilities than today. To offer more informative conceptual insights and capture the fact that supply chains are the dominant context for competitive advantages of firms (Crook and Combs 2007), we extend the original matrix according to a supply chain perspective, proposing that some ethical climates moderate causes of power imbalance and relational dependencies during unethical supplier exploitation. Figure 1 outlines the research framework.

Characterization of Unethical Supplier Exploitation

We answer the first research question by clarifying which properties mark buying firms’ actions as unethical exploitations of suppliers, therefore analysing how common business practices differ from unethical exploitative behaviours by confronting the economic viewpoint with the moral viewpoint. Although the former is presented in terms of the liberal paradigm of transactions—often referred to as egoistic profit maximization—the moral viewpoint is driven by Aquinas’s theory of fair prices (Aquinas 1920). Two definitions of unethical supplier exploitation are presented, a liberal and a fairness-oriented version, both of which are necessary to relate the economic to ethics literature and lay the groundwork for a debate and future research. Although supplier exploitation can take many forms (e.g. annexation of intellectual property, extension of payment terms, insurance issues, etc.), we refer, for simplicity, to demanding price concessions as unethical supplier exploitation, usually (in-) directly shifting margins from supplier to buyer

The Economic Viewpoint

Koehn (1992, p. 342) explains, “Exchange is born of a lack and a desire to fill that lack on the part of both parties to an exchange.” Thus, a transaction is based on the improvement of subjective values of both parties (Golash 1981), in the sense that the outcome of a transaction is mutually advantageous. From an economic viewpoint, it is difficult to determine the ethical problems associated with transactions since they are voluntary, reflecting the neoclassical liberal paradigm of transactions according to which justiceFootnote 2 during transactions is assured by markets and their corresponding processes.

Under this paradigm, if organizations or their representatives are aware of the conditions of a proposed transaction and agree to it voluntarily, the transaction is usually classified as fair (Nozick 1974). Milton Friedman, a primary liberal economist, argues that a transaction is ethically unobjectionable if it is “provided that the transaction is bi-laterally voluntary and informed” (Friedman 1962, p. 55). Companies, as actors, might act rationally in an economic sense if they pursue self-interest egoistically by maximizing profits (Frederiksen 2010). If everyone acts according to his/her interest and to rules of voluntary trade, every self-interested action harmonizes and adds to the promotion of the common good for society, as with Adam Smith’s invisible hand (Simpson 2009). Consequently, we define unethical supplier exploitation according to the neoclassical liberal perspective as

D liberal A buying firm’s (trans-)action is unethically exploitative if the firm prevents a supplier from acting in its self-interest to benefit during the transaction.

Accepting this liberal view, unethically exploitative transactions are those during which a buying firm coerces a supplier and/or withholds critical information deceptively or fraudulently. Any other realized transaction is not objectionable, prima facie.Footnote 3 Of course, according to this neoclassical liberal perspective, supplier exploitation can still occur. An Australian retailer, Coles, recently started an initiative called Active Retail Collaboration (Greenblat 2014a), alleged to seek extracting AUS $16 million from suppliers. After several reports and initial investigations, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission launched legal proceedings against Coles, seeking to support weaker suppliers and claims that Coles engaged in multiple unethical and unlawful actions. These allegations comprise the provision of misleading information to suppliers, use of undue influence and unfair tactics against suppliers, pursuit of payments without legitimate bases for the purpose of taking advantage of superior bargaining power, and most importantly, not providing sufficient time for suppliers to assess the costs of benefits and rewards associated with the program and threatening to withhold future business (Greenblat 2014a). Finally, Coles admitted unconscionable conduct in dealing with suppliers and agreed upon a $10 million penalty with ACCC (Bainbridge et al. 2014). Similar allegations were brought against Tesco (Butler 2013). Starting several years ago, Tesco has still not remedied shortcomings regarding their supplier management and is under suspicion having breached the industry’s code of practice (Ruddick and Ronald 2015).

From several perspectives, the liberal version of unethical supplier exploitation appears insufficient. We subsequently demonstrate the need for a moral perspective on supplier exploitation.

Criticism of the Purely Economic Viewpoint

Although many critiques of the purely economic viewpoint regarding supplier exploitation exist, we draw on one justified objection that demonstrates an incoherency in its ethical assumptions. The economic paradigm is shaped strongly by the idea of an agent that strives to maximize fulfilment of his/her perceived self-interest, often described as utility: the homo oeconomicus. Fundamentally, economists apply egoism not only heuristically, but also normatively as ethical egoism. Ethical egoism suggests it is necessary and sufficient for a morally correct action to maximize one’s self-interest (Shaver 2010). Supporters of the economic paradigm conceive needs and desires to be valuable (Bowie 1991) and are only concerned about others if they find benefit (Dienhart 2000). However, there are many sophisticated arguments and reasonable doubts against ethical egoism (Rachels 2002; Shaver 2010), and thus another version called rational egoism has been discussed as the most prominent version of egoism in business ethics research during the last decade (Locke 2006; Maitland 2002; Simpsons 2009; Woiceshyn 2011).

In its purest form, rational egoism suggests, “it is necessary and sufficient for an action to be rational that maximizes one’s self-interest” (Shaver 2010). Hence, rational egoism is not to be mistaken with cynical exploitation (Woiceshyn 2011, p. 315), which Maitland (2002, p. 6) describes as “selfishness”—a “concern with our self-interest that leads us to disregard the rights of others or, what may amount to the same thing, to neglect of our duties to them.” This enlightened version of egoism takes on a holistic perspective by relating the foundation of egoistic theory to rationality. By disregarding the idea that every action must fulfil the paradigm of utility maximization, rationality must be considered on a long-term time horizon. Although an action might benefit an actor in the short term, it remains unclear whether it also does so in the long term. This is the case concerning supplier exploitation.

Transferring the idea of rational egoism to the SCM context, exploitative actions can weaken the financial performance of buying firms’ supply bases, and therefore threaten the firm’s financial performance. This is especially true when a supplier suffers from liquidity difficulties, which can cause supply chain disruptions and inefficiencies. Buying firms increasingly depend on suppliers for development of innovative and high-quality products, which require collaborative approaches to SCM rather than adversarial ones (Quinn 2000; Zhang et al. 2009). Supplier exploitation reduces suppliers’ incentives to invest in innovative and high-quality products (Battigalli et al. 2007), which leads to lower quality and fewer consumer choices (Fearne et al. 2004), and might reduce total wealth not only in the supply chain, but also from an overall economic perspective. Hence, exploitative transactions affect suppliers and their corresponding shareholders immediately. From the perspective of rational egoism, buyers who make these exploitative decisions act on “false ideas which require correction, not gratification” (Locke and Woiceshyn 1995, p. 410). It is barely rational to act exploitatively, for the sake of short-term benefits annulled by damages in the long term.

The Moral Viewpoint

The criticism stated above supports the inclusion of other ethical values such as justice, honesty, and integrity (Woiceshyn 2011). From this viewpoint, justice is a matter of self-interest. Treating others objectively and giving them what they deserve through equal exchanges of value is necessary from a rationally egoistic viewpoint. By pursuing self-interest, people depend on others (Smith 2006), but if they lack perceived justice, they are likely to stop collaborating, even if transactions are mutually advantageous (Güth et al. 1982). Another theoretical perspective needs to be applied to introduce justice into unethical supplier exploitation.

Exploitation is always an act of acquisition of benefits, and “gaining some benefit is the aim of every act of exploitation” (Mayer 2007, p. 139). The liberal paradigm of business emphasizes generation of profits as the only legitimate goal of companies (Friedman, 1970). However, to what extent is the acquisition of benefits (the transaction) just or unjust? Mayer (2007, p. 142) argues that unethical exploitation during transactions occurs because an exploiter gains at an exploitee’s expense in the sense that the former fails to benefit the latter “as some norm of justice requires.” In the case of unethical supplier exploitation, unjust means that buying firms do not allow exploited suppliers to benefit sufficiently. Golash (1981, p. 321) suggests, “What is at stake in exploitation…is not only the methods used but also the actual result of the bargaining process—that is, the exchange of a commodity at less (or more) than its objective value.” This is similar to Mayer’s (2007) argument, which distinguishes undeserved and relative (in contrast to absolute) losses at an exploitee’s account as the salient element during unfair (unethically exploitative) transactions. During scenarios of supplier exploitation, the performance of exploitees (i.e. supplier) is not valued as it should be; suppliers do not receive the correct amount of money for their goods. Although they add value to products and services through operations, they are not paid accordingly, but to the degree to which the buying firm has external options available. As Golash (1981, p. 323) mentions, “the concept of exploitation requires a distinction between price and value, for it entails that there are some sorts of circumstances that affect price but not value.”

Consider Walmart’s introduction of radio frequency identification (RFID), as Drake and Schlachter (2008) discuss. The new technology enabled Walmart to improve logistic processes, but the company was unwilling to cover extra costs imposed on suppliers to attach RFID tags to their products by paying higher prices. This demonstrated how price did not reflect the increase in value, but was a consequence of Walmart’s superior market power (Drake and Schlachter 2008). Some critics suggest suppliers benefit ex post in comparison to ex ante since the transactions are mutually advantageous, which is true if we consider the situation against the background of a non-cooperation baseline (Wertheimer and Zwolinski 2013). For example, suppliers experience even greater losses if they do not cooperate. From this perspective, the alleged exploitative transaction is Pareto superior. However, this is true only in absolute terms; in relative terms, the exploiter should have provided better conditions for the transactions according to reasons of justice (Mayer 2007) and the justice baseline (Wertheimer and Zwolinski 2013), according to which the exploitee undeservedly loses, making the transaction Pareto inferior.

Requirements for fairness in buyer–supplier relationships can be broken down and linked to Aquinas’s just price (Aquinas 1920). Mayer (2007, p. 145) defines just price as the price that “a non-disadvantaged party would accept.” This concept comprises the idea that the just price of a transaction is the equilibrium price in a competitive market, but the equilibrium price does not exist in unethically exploitative transactions due to the disadvantages of one party. Powerless suppliers are exploitable since they are vulnerable. Suppliers might depend on particular buying firms because a large share of their sales is achieved with one buying firm. If the buying firm threatens to cease the relationship, potential consequences might be more severe than if the supplier accepted the exploitation. Thus, the core aspect is: if the supplier’s disadvantages (i.e. vulnerabilities) did not exist, it would be reasonable to expect that just prices resulted. Hence, by assuming a hypothetically competitive market (Wertheimer and Zwolinski 2013), we anchor the decision concerning unethical exploitative transactions to the outcome of a perfect market that presumably would render a just price during a transaction. Golash (1981, p. 324) rephrases this idea by stating, “A exploits B if and only if A uses factors that give him more bargaining power but do not affect the value of the commodity exchanged to obtain a bargain [transaction] more favorable to him than would otherwise be possible.” To transfer this discussion to a buyer–supplier context, we define:

Dfair A buying firm’s (trans-)action is deemed unethically exploitative if the firm gains undeserved benefits at the supplier’s expense through unjust prices that would not come about in a hypothetically competitive market.

Antecedents of Unethical Supplier Exploitation

We adopt D fair when focusing on antecedents that provide insights regarding under which circumstances firms pursue unethical supplier exploitation. We highlight power imbalance, sources of power and mutual dependence since exploitative practices are possible only if sufficient power is present. We conclude with several propositions.

Power

In one of the most common definitions, Weber (1947, p. 152) describes power as “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests.” In line with other scholars such as Russell (1938) and Dahl (1957), Weber employs a conception of power that must be understood as relational capacity. According to this stream of literature, power is power over actors. From a logical viewpoint, suppliers do not voluntarily agree to be exploited in a self-harming way, but they do so only because they are forced by buying firms that have power over them. Hence, for unethical supplier exploitation to exist, a buying firm must have some type of power over a supplier.

Power and dependencies are usually far from equal distribution in corporate practice (Nyaga et al. 2013). The control of resources through power advantages allows a superior, egoistic, buying firm to skim generated surplus from the dyad (Cox 1999; Williamson 1975), and hence, many buying firms strive to create these imbalances (Emiliani 2003; Hingley 2005). Studies in the SCM context focus on asymmetric power distribution and resulting dependencies, which affect quality issues (Battigalli et al. 2007), performance (Crook and Combs 2007), strategic supply chain decisions (Ireland and Webb 2007), social responsibility (Hoejmose et al. 2013), and relationship commitment and collaboration (Kähkönen 2014). To understand the impact of power on supplier exploitation, it helps to analyse various sources that enable actor A to influence the behaviour of B in a way the latter did not choose on its own, resulting in exchange relationships and evolving dependencies between firms (Emerson 1962). Since power is a complex construct and sociologically amorphous (Weber 1947), various sources of power exist that have varying effects on phenomena under investigation (Ke et al. 2009). According to French and Raven (1959), bases of inter-organizational power fall into five categories: reward, coercive, legitimate, referent and expert (Table 2). These sources of inter-organizational power imbalance have been exposed to various categorizations, among which the most prominent is that between mediated and non-mediated (Johnson et al. 1993; Maloni and Benton 2000). We follow this categorization.

Mediated power sources usually include coercive, reward and legal legitimate since these three can be controlled by the buying firm, which decides, as a source of power, whether, how and when it influences a supplier (Nyaga et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2008). Mediated power might lead to higher probabilities of unethical supplier exploitation since the buyer has the ability to force a supplier. Although reward power includes the option to benefit suppliers by extending business with them, it carries the same mediated power logic as coercive power since denial of expected rewards is a type of coercion. Both tactics allow powerful buying firms to limit or cease business that threatens suppliers (Nyaga et al. 2013). If a supplier depends on a buying firm and these options endanger its existence to some degree, it is apparent that mediated power sources have the potential for unethical supplier exploitation. Reward and coercion are thus sides of the same coin. Legal legitimate power stems from contracts, as another form of mediated power. If a buying firm has this type of power over a supplier, it is usually because contracts contain performance demands the supplier must fulfil. This contractual legitimacy acts as a door opener for unethical supplier exploitation under the veil of quasi-legality. Hence, transferring the discussion of power imbalances caused by mediated power sources to the phenomenon of unethical supplier exploitation, we postulate the following proposition:

Proposition 1a

Power imbalances stemming from mediated (i.e. coercion, reward and legal legitimate) power sources cause unethical supplier exploitation.

Non-mediated power sources—referent, expert and traditional legitimate—stem from the perception of power on the side of a less powerful agent. While in the case of non-mediated power, a supplier decides how far a buying firm influences it (Zhao et al. 2008), mediated power sources “control the reinforcements which guide the target’s behavior” (Tedischi et al. 1972, p. 292). Non-mediated power sources such as referent power imply a “hope to be closely associated with the dominant firm,” based on emotional ties (Ke et al. 2009, p. 840), and that is unlikely the case during exploitation. If a supplier is treated unfairly, it is inconceivable that it will continue to admire the buyer and respect it as a type of leader to which it feels attracted. If a buying firm uses referent power negatively, it is likely to lose power. The same holds for expertise and traditional power sources. If a supplier perceives misuse of non-mediated power, it is likely to resist this former source and refrain from the buying firm’s attractiveness. Therefore, we postulate the following proposition:

Proposition 1b

Power imbalances stemming from non-mediated (i.e. referent, expertise and traditional legitimate) power sources do not cause unethical supplier exploitation.

Mutual Dependence

Hingley (2005) suggests that an asymmetric distribution of power does not necessarily result in unsatisfied or exploited suppliers. Suppliers usually accept this state as long as they receive a share they consider as a “reasonable proportion of the relationship value” (p. 853). Hence, power imbalances and unethical supplier exploitation are not necessarily tied if fairness is applied during a relationship; power imbalances are not by nature destructive or negative regarding their outcomes. This accords with Kumar (2005), who warns against considering power uni-dimensionally. In terms of power, both actors during a transaction are to some degree dependent on each other (Casciaro and Piskorski 2005). In a dyad, differing values of power imbalance—the difference between two actors’ dependencies (Lawler and Yoon 1996)—can coincide with a range of mutual dependency values—the sum of A’s dependence on B and actor B’s dependence on actor A (Bacharach and Lawler 1981), and vice versa (Fig. 2). Kumar (2005) stresses the disparity if power asymmetries are characterized by low or high mutual dependence since the high variety might bring about more trust and consequently lower conflict between parties.

Configurations of power imbalance and mutual dependence (adapted and modified from Casciaro and Piskorski 2005)

We apply this general illustration to elaborate the emergence of unethical supplier exploitation. Unsurprisingly, the mere existence of power imbalances does not suffice to explain unethical supplier exploitation. Configuration 1 describes B’s dependence on A as low (1), while A’s dependence on B is high (7), resulting in a high power imbalance (6), which is calculated as the difference between both values, and a medium value for mutual dependence (8), which is calculated as the sum of both values. This value of mutual dependence might be deceptive if we compare configuration 1 with configuration 5, in which mutual dependence between A and B is the same. Yet configuration 5 is not marked by power imbalance, making supplier exploitation impossible. A difference in mutual dependence is decisive during other scenarios. Considering configurations 2 and 4, we ascribe both scenarios the same power imbalance (3). Therefore, a buyer’s propensity to exploit a supplier should be nearly the same. However, these scenarios differ concerning the value for mutual dependence (11; 5). Configuration 2 suggests stakes are high for both firms, making an exploitative scenario regarding a supplier unlikely since both firms might be interested in maintaining a stable relationship.

In line with Hibbard et al. (2001), Kumar (2005) states that the higher the total amount of mutual dependence within a relationship, the less likely punitive tactics are applied by the more powerful party. Gulati and Sytch (2007) highlight these effects of embeddedness that result from joint dependence. Embeddedness makes dyadic relationships less instrumental since it leads to higher trust and information exchange (Gulati and Sytch 2007; Heide and Miner 1992). Hence, we suggest the following proposition:

Proposition 2

If the power imbalance (from mediated sources) between a buying firm and supplier is the same in two scenarios, unethical supplier exploitation becomes more likely in that one, which is marked by lower mutual dependence.

Moderation by Ethical Climate

The previous propositions link power induced in buyer–supplier dyads with unethical supplier exploitation consequently. Although these preconditions often translate into supplier exploitation in industries such as automotive and retail, as previous examples suggest, several exceptions such as Honda, Toyota and Sony with similar preconditions do not result in similar, unethical supplier exploitation (Lindgreen et al. 2013). This implies that the previous propositions must be refined because the relationship between power imbalances and mutual dependence, and supplier exploitation, might be moderated since power imbalances can remain unexercised in supply chain relationships (Cox et al. 2001b; Howe, 1998).

Similar to Kim (2000), we propose that the ethical climate in which decisions are made moderates the links among power asymmetries, mutual dependencies, and unethical supplier exploitation. Research on ethical climates was one of the most important scholarly influences in business ethics (Martin and Cullen 2006), with a “consistent link between ethical climate and ethical outcomes” (Arnaud and Schminke 2012, p. 1768). In the following discussion, ethical climate, which is “the prevailing perceptions of typical organizational practices and procedures that have ethical content” (Victor and Cullen 1988, p. 101), is introduced as a moderator. In Victor and Cullen’s (1988) argument, the ethical climate of an organization constitutes a normative framework in which employees and managers respond to the Socratic and Kantian question “what should I do?” during moral dilemmas (Victor and Cullen 1988, p. 101). It usually determines which ethical criteria individuals use to approach and assess these situations (Cullen et al. 1989). “The types of ethical climates existing in an organization or group influence what ethical conflicts are considered, the process by which such conflicts are resolved, and the characteristics of their resolution” (Victor and Cullen 1988, p. 105). Ethical climates consist of two dimensions, influencing what is right and wrong ethical behaviour within an organization (Victor and Cullen 1988).

The first dimension encompasses three typical ethical decision-making criteria—egoism, benevolence and principle. These criteria stem from threeFootnote 4 philosophical viewpoints concerning ethics: egoism, consequentialism and deontology. Although egoism assumes that the best ethical behaviour maximizes self-interest (Crane and Matten 2007), utilitarianism ignores the partial perspective of a single agent, requiring maximization of the sum of utility (usually defined as happiness or pleasure) for those affected by the decision that must be made (i.e. the best consequences for the highest quantity of people) (Mill 2007; Singer 1972). In contrast, deontological ethics in the broadest sense judges right and wrong ethical behaviour according to abstract principles, rules and moral laws, which must be considered during decision-making; acts are wrong or right regardless of the consequences (Crisp 1995; Micewski and Troy 2007). Extant studies suggest that one of the three decision-making criteria dominates ethical climates (Martin and Cullen 2006).

The second dimension differentiates three loci of analysis—individual, local and cosmopolitan. Each locus refers to “referent group(s) identifying the source of moral reasoning used for applying ethical criteria to organizational decisions and/or the limits on what would be considered in ethical analyses of organizational decisions” (Victor and Cullen 1988, p. 105). For example, if the locus of analysis is local, ethical decisions are made in a way in which the organization (or subunit) is the central object of reference for one’s actions. Thus, these aspects are prioritized over individual or cosmopolitan ones. When the locus of analysis is cosmopolitan, ethical decision-making transcends local (i.e. organizational) contexts, incorporating societal aspects during moral reasoning. With individual locus, individuals make their own ethical decisions based on their own moral norms and beliefs (Martin and Cullen 2006). Figure 3 depicts Victor and Cullen’s (1988) nine-field matrix of original theoretical ethical climates.

Original matrix of Victor and Cullen (1988)’s theoretical ethical climate models

Supply Chain Climates

As manifestations of normative values in organizations, ethical climates guide manager and employee behaviour (Arnaud and Schminke 2012; Victor and Cullen 1988), and thus presumably moderate firms’ propensities to exploit less powerful suppliers. However, when Victor and Cullen introduced the theory in 1988, the role of SCM in companies was dissimilar to today. SCM gained in both importance and complexity over the last few decades (Trent and Monczka 2003), and its functions evolved from tactical units to strategic ones, with high organizational impact particular with regard to purchasing units (Carter and Narasimhan 1996). Since buying firms spend approximately 50–75 % of their revenues on purchasing volumes (Lindgreen et al. 2013), SCM contributes to corporate performance, making it a pillar of a firm’s economic success (Carr and Pearson 1999; Mabert and Venkataramanan 1998; Quinn 1997). To provide a suitable research model with sound explanations for a firm’s propensity to exploit suppliers unethically, we extend ethical climate to SCM, and propose a new supply chain locus of analysis. By doing so, we determine propositions that fill the gap between power and dependencies on one side and unethical supplier exploitation on the other.

Many studies suggest that subunits in organizations develop different homogeneous ethical climates (Victor and Cullen 1988; Weber and Seger 2002), and loci of analysis with different ethical decision-making criteria might exist, referring to departments in a firm (Martin and Cullen 2006; Treviño et al. 1998; Weber 1995). However, research omits extension of ethical climates according to SCM contexts. SCM decision-making contexts are framed not only by individual, organizational and cosmopolitan loci of analysis, but also by a supply chain’s perspective in which buyer–supplier relationships are important and supply chain competition has to some degree replaced competition among single firms (Crook and Crombs 2007). Fritzsche (2000) argues that different referent groups (i.e. loci of analysis) comprehend groups of stakeholders that are relevant to a decision-making context. The SCM function in a firm is boundary spanning, linking the organization with key external environment individuals (Weber 1995) with which other organizational members usually do not come in contact. Research on sustainable SCM emphasizes the role of suppliers as important referent groups during ethical decision-making (Klassen and Vereecke 2012). Wrongdoings at suppliers’ sites are increasingly ascribed to the sphere of influence of buying firms, entailing risks such as negative publicity, reputational damage and litigation (Carter and Jennings 2004). According to Victor and Cullen’s (1988) theoretical ethical climate matrix, we propose a supply chain locus of analysis to understand exploitation better (Fig. 4). Three climates resulting from the supply chain locus of analysis are similar to Victor and Cullen’s (1988) climates of local (organizational) locus: focal firm profit, partnership and contracts. We discuss these new climates in detail, and demonstrate their moderation of power and unethical supplier exploitation.

Focal Firm Profit (Egoism)

Egoistic climates serve both organizational and personal benefits (Wimbush and Shepard 1994). Applying egoistical decision-making criteria to a supply chain locus of analysis results in a climate in which the profitability of the supply chain is the most important parameter during ethical dilemmas. The competitiveness of supply chains replaced the old model in which firms competed (Crook and Combs 2007; Vickery et al. 1999). Crook and Crombs (2007) investigate the question of how supply chain profits are distributed among members of a supply chain, emphasizing that supply chain profit consists of two components: The sum of all value added from individual supply chain members and SCM gains that result from use of collaborative SCM. The total supply chain profit can be distributed either (equally) in advance to all supply chain members (they appropriate pre-SCM profits and a proportional share of SCM gains) or beneficially to the more powerful firms. Among other factors, this depends on power distribution in a supply chain (Crook and Crombs 2007), as propositions 1 and 2 suggest. If the latter is true, these powerful actors are able to “take a disproportionate share of SCM gains, all SCM gains, or even take all SCM gains plus some of the weaker firms’ pre-SCM profits” (Crook and Crombs 2007, p. 547).

In focal firm profit climates, buying firms manage even their important suppliers in an arm’s length, non-collaborative way based on spot market transactions, with short-term commitment focused on cost and quality (Cox et al. 2001a). In these egoistically driven contexts (Cox 1999), power is an instrument for skimming surplus from suppliers, and hence the focal firm strives for power advantages by possessing or controlling strategically important resources (Berthon et al. 2003). Suppliers are conceived as adversaries and buying negotiations as zero-sum games (Lindgreen et al. 2013). In this climate, supply chain managers are supposed to be incentivized by pure savings related to purchasing volumes. Drake and Schlachter (2008, p. 852) describe these business relationships in which firms are powerful enough “to force other firms in [their] supply chain to provide…benefit[s]…without sharing the gain with the other firms,” as “dictatorial collaboration.” Thus, we postulate the following proposition:

Proposition 3

Focal firm profit climate moderates power imbalances/mutual dependencies and unethical supplier exploitation in the sense that focal firm profit climates make unethical supplier exploitation more likely.

Supply Chain Partnership (Benevolence)

By cooperating with partners in their supply chains, firms might gain higher, mutual, competitive advantages in comparison to neglecting partnerships (de Leeuw and Fransoo 2009). This is usually achieved through collaborative actions such as sharing knowledge and costs, building relationship-specific assets, pooling technology and information and creating economies of scale (Dyer and Singh 1998, Hingley 2005). Apart from this, buyer–supplier relationships gain value through both direct and indirect functions. For example, if a customer buys goods from a supplier that has high innovation potential, developed within another relationship, the buying firm might also benefit from this capacity in the future (Lindgreen and Wynstra 2005). Hence, collaborative approaches to SCM gained increased importance in theory and practice (Flynn et al. 2010; Wisner and Tan 2000) since they provide additional, relational rents (Fu and Piplani 2004; Gulati and Sytch 2007) and improve firms’ operational performance (Devaraj et al. 2007).

Generally, supply chain partnership climates are characterized by commitment to relationship partners, trust, solidarity, and expected mutuality and continuity (Dwyer et al. 1987; Johnston et al. 2004; Poppo and Zenger 2002). These collaborative relationships generate positive outcomes for both suppliers and buying firms, with the idea that each supplier adds value (Lindgreen et al. 2013). Although powerful buying (focal) firms have the opportunity to skim all benefits generated in these supply chain partnerships, they would rather spend financial benefits as quasi-investments to uphold the relationship, at least with some suppliers. These collaborative practices increase the likeihood of mutually beneficial, win-win situations that might even benefit all members of the supply chain (Fearne et al. 2004; Tan 2002). Regarding moderation in a supply chain partnership climate, we offer the following proposition:

Proposition 4

Supply chain partnership climate moderates power imbalances/mutual dependencies and unethical supplier exploitation in the sense that supply chain partnership climates make unethical supplier exploitation less likely.

Supply Chain Procedures and Industry Codes (Principle)

As a combination of the principle dimension and a supply chain locus of analysis, we propose a third climate supply chain procedure and industry code similar to the cosmopolitan and organizational principle climate. Concerning these climates, firms jointly generate formal agreements valid for a production process or supply chain since these already exist for industries. These agreements are usually presented in the form of industry codes of conduct such as the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC) code of conduct, the pharmaceutical industry principles for responsible supply chain management of the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Initiative (PSCI), and the code of business practice of the International Council of Toy Industries (ICTI). Approaches exist in which principles for SCM are generated such as the principles and standards of ethical supply management conduct launched by the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). After recurring incidents in which U.K. buying firms misused power to streamline supply bases and gain excessive benefits, the U.K. Competition Commission issued a first U.K. supermarket code of practice in 2002, developing and strengthening it with the Grocery Supply Code of Practice (GSCOP) in 2010. Since 2013, there is also a code adjudicator to oversee compliance (Bowman 2013). One of three principles of the GSCOP is “that all trading partners should be treated fairly and reasonably” (Fearne et al. 2004, p. 4). Although research suggests conflicting results for the direct relationship between implementation of codes of conduct and (un)ethical behaviour as a dependent variable (Blome and Paulraj 2013; Kaptein and Schwartz 2008), commitment to these principles and codes affects supply chain managers and ethical climates positively (Treviño et al. 1998), especially if fair competition and just prices are explicit, and thus we suggest:

Proposition 5

Supply chain procedures and industry codes of conduct climate moderate power imbalances/mutual dependencies and unethical supplier exploitation in the sense that supply chain procedures and industry codes of conduct climate make unethical supplier exploitation less likely.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications

Our research interest culminated from two research questions that asked for a definition of unethical supplier exploitation and exploration of antecedents of this phenomenon. Concerning the latter, we investigate the role ethical climates play during the emergence of unethical supplier exploitation. Accordingly, the theoretical contributions of this article are threefold. First, we introduce unethical supplier exploitation, and from this perspective, we contribute to literature on supply chain management and business ethics in the inter-organizational research field (Saini 2010). We do so through extensive review of literature and systemically contrasting a liberal economic viewpoint, with a moral and fairness-oriented viewpoint of supplier exploitation. As a concept to distinguish these sides of the same coin, Aquinas’s (1920) just price is combined with Wertheimer and Zwolinski’s (2013) hypothetically competitive market. We develop two definitions of unethical supplier exploitation. Starting with the liberal definition (D liberal), we show that unethically exploitative transactions are usually those during which a buying firm coerces a supplier and/or withholds critical information deceptively or fraudulently. Since the perspective does not disqualify voluntary agreements between buying firms and suppliers, which obviously disadvantage the latter, we present a second fairness-oriented definition. D fair requires buying firms to compensate suppliers according to equity principles that apply in hypothetically competitive markets. This merit principle guarantees fair treatment of suppliers and is hence the way in which supplier should be managed.

Although buying firms should strive to negotiate a price that enables them to market goods in a competitive context, they should at least aim for prices that approach the fairness rather than non-cooperation baseline, preventing unethical supplier exploitation. Our findings clarify concepts and offer principles for managerial behaviour. As is true with philosophical and ethical considerations, this might not be an overall or (for some people) satisfying solution. However, it is a first step in the right direction in the sense that awareness of this practice has risen and it might be scrutinized in future research and through managerial reflection.

Regarding the second research question, we present power imbalance, sources of asymmetries and mutual dependence as antecedents that influence unethical supplier exploitation. According to nearly all prominent and sophisticated definitions of what characterizes power, theorists reply with an actor’s ability to force (regardless of on what the capability to do so rests) other actors to act according to his/her will. Since being exploited is most certainly undesired by suppliers, buying firms need to be in a position of power over suppliers. This state can be achieved through five factors, according to French and Raven (1959), which can be divided into mediated and non-mediated power sources. Most likely, buying firms occupy a better market position and are capable of switching suppliers. If they use this power to threaten a supplier with termination of business, they possess coercive mediated power, which is often the case in retail and automotive industries (cp. Table 1). We argue that non-mediated power sources do not lead to unethical supplier exploitation since such sources stem from the perception of power on the side of the less powerful agent. Buying firms do not control these sources of power, but suppliers do (Zhao et al. 2008). The degree of power imbalance does not predict unethical supplier exploitation, as practical counterexamples such as Toyota and Honda suggest.

We suggest that how much a relationship with a supplier is marked by interdependency influences propensity to exploit such that high mutual dependency decreases exploitation behaviour. This becomes clear if one thinks of a dyad in which both parties are powerful and rely on each other because they share high asset specificity or high sales, and respective purchasing volume regarding the same product. Their mutual dependency prevents them from destructive actions since too much is at stake for both parties. In line with the extant studies (Blome and Paulraj 2013; Kim 2000), we propose that the ethical climate in which purchasing decisions are made is an important moderator, which must be considered during ethical decision-making. This study differs from other ethical climate research such as Blome and Paulraj (2013), who focus on benevolence climate, and Gonzalez-Padron et al. (2008), who do not differentiate dimensions of ethical theories.

Third, this article goes beyond extant research on ethical climate theory since we extend Victor and Cullen’s (1988) ethical climate theory according to a supply chain dimension. This extension is necessary because SCM gained increasing strategic importance during times of increasing supply chain complexity (Trent and Monczka 2003), and with supply chain competition as a new paradigm (Crook and Combs 2007). We propose ethical climate as a moderator among power imbalance, dependencies and unethical supplier exploitation. We also propose that organizational factors influence generation of ethical climates (Martin and Cullen 2006; Weber 1995). We act on the suggestion that ethical climates vary across functional departments, and suggest that an extension of Victor and Cullen’s (1988) climate matrix captures decision-making criteria in inter-organizational contexts better.

Applicability from a Managerial Perspective

To find the right approach to managing suppliers, managers of powerful buying firms possess two intra-organizational instruments with which they can avoid emergence of unethical supplier exploitation: (1) influencing the configuration of ethical climates and (2) thinking in suppliers’ shoes.

(1) Executive leaders of buying firms might try to provide an organizational ethical climate that fosters the right ethical behaviour (Treviño and Brown 2004). Unethical behaviour is not only bad itself (from an ethical viewpoint), but can also affect a firm’s reputation, and eventually financial performance, negatively (Carter 2000; Carter and Jennings 2004). Much research investigates antecedents of ethical climates, and generally, three arrays of antecedents have been identified: external organizational context, organizational form and strategic/managerial orientations (Martin and Cullen 2006). Buying firm managers influence the latter two to prevent exploitative buying behaviour. These two areas are subdivided into formal and informal means (Tenbrunsel et al. 2003; Treviño et al. 1998). Formal instruments are usually documented, standardized (Pugh et al. 1968) and are visible inside and outside the firm (Tenbrunsel et al. 2003); these include aspects such as formal and recurrent communication, formal policies (e.g. codes of conducts), leadership and authority structures, socialization mechanisms and decision processes, ethical training programs, formal surveillance and formal sanctions/rewards (Rottig et al. 2011; Treviño et al. 1998). Informal measures are neither documented nor standardized; employees and managers receive these latent signals and perceive them (Tenbrunsel et al. 2003). This group comprises ethical norms, implicit peer behaviour, role models, rituals, historical anecdotes, and language (Ardichvili et al. 2009; Cohen 1993; Treviño et al. 1998). Research demonstrates that both formal and informal factors influence ethical climates (Blome and Paulraj 2013; Rottig et al. 2011). For example, codes of conduct, combined with training on code contents and communication activities regarding ethical issues, increase moral awareness and thus ethical behaviour (Kaptein and Schwartz 2008; Rottig et al. 2011). However, if these codes remain unembedded in a compliance system, with monitoring, sanction, and reward mechanisms, the mere existence of codes is unlikely to encourage ethical behaviour (James 2000; Robertson and Rymon 2001).

(2) To enrich this discussion about fair decisions from a buying firm’s perspective, with theoretical underpinnings from justice theory, Rawls’s (1999) components are appropriate. When Rawls discusses a “veil of ignorance,” he describes a primary feature of his “justice as fairness.” The veil is a thought experiment to ensure “pure procedural justice at the highest level” (p. 104) by incorporating impartiality and fairness (Freemann 2012) during negotiation. During the experiment, free and equal people who are negotiating which principle(s) of justice to adopt voluntarily operate under a veil of ignorance; they do not know about their personal, social and historical characteristics and circumstances (Rawls 1999). Rawls (1999) uses this instrument to create a fair, original position at which no one is able to benefit from his or her capabilities or position in society. Taking this as an example of how justice could be accounted for in buyer–supplier relationships, managers who are in a negotiation with the suppliers could imagine they do not know how powerful they are, and they might be the supplier once the veil rises. Managers who take this perspective as a starting point by thinking of themselves in suppliers’ shoes are probably more willing to pay adequate and fair prices. Anonymous bidding, being one partial, practical implementation of this theoretic thought experiment, could be considered to foster markets that are more competitive.

Besides these intra-organizational implications, this study has inter-organizational managerial applicability, which should not be overlooked. It provides a frame of reference for executives according to which they can delineate unethical and common business practices. This is particularly important in terms of collaborative approaches to SCM. Suppliers perceiving unfair compensation might be more suspicious towards powerful buying firms. However, trust and commitment, as factors of collaborative relationships, are fostered in dyads in which a weaker party perceives fair treatment (Scheer et al. 2003). Close collaboration in turn can be mutually beneficial and increase performance within dyads through additional relational rents (Dyer and Singh 1998; Fu and Piplani 2004; Gulati and Sytch 2007). Although unethical supplier exploitation might offer short-term benefits, which can be seducing to buying managers, myopic management should be avoided since it causes strenuous opposition from suppliers and therefore results in greater costs than benefits.

Limitations and Future Research

This article includes limitations that offer opportunities for future research. What we describe as justice throughout the paper is only one dimension of the construct, distributive justice. Scholars point out that justice perceptions within inter-organizational relationships are at least twofold, and the other component, procedural justice, must be considered too (Fearne et al. 2004; Kumar 2005). Since questions concerning unethical supplier exploitation are a matter of how outcomes and profits are shared between buying firms and suppliers, distributive justice is the more important perspective for the purpose of this study. However, future research should investigate the effects of procedural justice on the phenomenon. Although the ethical climate within which potential exploitative decisions are made serves as a powerful moderator, personal attitudes of decision-makers and cultural aspects might contribute to a more holistic research model (Beekun and Westerman 2012; Fritzsche and Oz 2007). For example, particularly in Japanese firms, dominant Keiretsu approaches influence how sourcing decisions and negotiations are made (Brett and Okumura 1998). Although extant research operationalizes and validates the constructs in our model, identification of unethical supplier exploitation as a dependent variable remains difficult. Besides the difficulty of assessing price in a hypothetically competitive market, buying firms likely engage in strong social desirability bias, and hence deny exploitative behaviours on surveys and during interviews. At least some suppliers experiencing self-inflicted financial problems accuse powerful buying firms of exploitation rather than acknowledge their own faults. However, research design can protect against biases of this sort. This study is limited to situations in which buying firms possess superior power over suppliers because in those situations, ethical concerns are particularly important. However, suppliers might also engage in unethical behaviour, which in turn provokes responses from buying firms. Future studies should recognize actions and perspectives that focus on the supply side of the buyer–supplier relationship (Fearne et al. 2004). Although some results appear transferable to dyads characterized by dominant suppliers, some do not. By demanding price concessions, a powerful buyer might harm itself little. However, if a powerful supplier engages in the analogue of demanding regular price increases, the buying firm ultimately passes this increase to customers, which in turn reduces demand and thus harms the supplier. Therefore, ethical considerations of dominant suppliers need to focus on various aspects. When suppliers possess monopolistic power, artificial limitations on production quantities to increase marginal profits are often not only unethical but also illegal since they reduce the wealth of the nations.

Conclusion

Abusive power tactics such as unethical supplier exploitation are more often the case in states of power imbalances than expected (Fassin 2005; Hingley 2005). The intuitive objection that the weaker supplier would not endure such practices is invalid since it might have no exit option. This is, among others, a reason power-imbalanced buyer–supplier relationships are not unstable, per se (Hingley 2005). Thus, ethical considerations should and do play a role in global organizational decision processes, and in management research (Saini 2010; Shin 2012). This article is among the first to set unethical supplier exploitation in the agenda of scholarly research, providing a consistent research model of its antecedents and moderation of ethical climates from an SCM perspective (Fig. 5). The findings contribute to the body of knowledge on ethical supply chain management in general and extend the theory on ethical climates through the integration of a supply chain perspective. Within the realm of ethical supply chain management, we ground the concept of unethical supplier exploitation for future empirical research.

We encourage both researchers and practitioners to think outside the box and challenge common business practices. Powerful buying firms might be in a position to force suppliers to act according to their will, but these actions might be questionable, at least from a moral viewpoint. Although it is alleged that ethical climates make unethical supplier exploitation more likely, this article does not recommend how to treat suppliers from a buying firm’s perspective. Buyer–supplier relationships are always contextualized, and there exists no single method of managing these relationships in all circumstances (Cox et al. 2001a). Firms should provide a mixture of purchasing practices and align the right approach to the appropriate suppliers (Lindgreen et al. 2013). However, even if transactional and profit-gaining approaches to SCM are reasonable during some scenarios, firms should play fair.

Notes

Based on the idea that exploitation has semantically always the same particular meaning and that moral opinions matter in identifying unethical exploitation, some authors describe both practices as exploitation (Feinberg, 1988; Wood, 1995). Wood (1995) distinguishes innocent exploitation and non-innocent exploitation, and Mayer (2007) adds a wrongful element to distinguish unethical exploitation. Due to its often pejorative connotation, we favor “exploitation” in cases in which unethical exploitation occurs. Hence, we discuss common business practice in ethically neutral cases, and refer to the opposite as unethical exploitation.

The terms justice and fairness are used interchangeably throughout this manuscript, following scholars such as Andre and Velasquez (1990).

Classic agency theory, which shares many assumptions with neoclassical economics, advocates the view that despite maximization of their own utilities (or happiness), actors are not inclined to apply additional morality, and even act immorally, if opportunism is perceived (Bøhren 1998; Fontrodona and Sison 2006).

Ethical egoism is often perceived as a sub-category of consequentialism, promoting the best consequences for the moral agent.

References

Andre, C., & Velasquez, M. (1990). Justice and fairness. Issues in Ethics, 3(2). Accessed June 30, 2014, available at http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v3n2/.

Aquinas, T. (1920). Summa theologica. London: Burns Oates & Washbourne.

Ardichvili, A., Mitchell, J., & Jondle, D. (2009). Characteristics of ethical business cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 445–451.

Arnaud, A., & Schminke, M. (2012). The ethical climate and context of organizations: A comprehensive model. Organization Science, 23(6), 1767–1780.

Bacharach, S. B., & Lawler, E. J. (1981). Power and tactics in bargaining. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 34(2), 219–233.

Badenhorst, J. (1994). Unethical behaviour in procurement: A perspective on causes and solutions. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(9), 739–745.

Bainbridge, A., McGrath, P., & Janda, M. (2014). Coles admits unconscionable conduct in dealing with suppliers; $10 million penalty agreed with ACCC. In: abc.net (December 15, 2014). Accessed January 29, 2015, available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-12-15/coles-accc-reach-settlement-on-supplier-conduct/5967476.

Battigalli, P., Fumagalli, C., & Polo, M. (2007). Buyer power and quality improvements. Research in Economics, 61(2), 45–61.

Beekun, R., & Westerman, J. (2012). Spirituality and national culture as antecedents to ethical decision-making: A comparison between the United States and Norway. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(1), 33–44.

Berthon, P., Pitt, L. F., Ewing, M. T., & Bakkeland, G. (2003). Norms and power in marketing relationships: Alternative theories and empirical evidence. Journal of Business Research, 56(9), 699–709.

Blome, C., & Paulraj, A. (2013). Ethical climate and purchasing social responsibility: A benevolence focus. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 567–585.

Bloom, P. N., & Perry, V. G. (2001). Retailer power and supplier welfare: The case of Wal-Mart. Journal of Retailing, 77(3), 379–396.

Bøhren, Ø. (1998). The agent’s ethics in the principal-agent model. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(7), 745–755.

Bowie, N. E. (1991). Challenging the egoistic paradigm. Business Ethics Quarterly, 1(1), 1–21.

Bowman, A. (2013). UK appoints regulator to protect grocery suppliers. In: ft.com (June 10, 2013). Accessed June 30, 2014, available at: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/48e059ee-dda9-11e2-892b-00144feab7de.html#axzz368RECYjq.

Brett, J. M., & Okumura, T. (1998). Inter- and intracultural negotiation: U.S. and Japanese negotiators. Academy of Management Journal, 41(5), 495–510.

Burritt, C., Wolf, C., & Boyle, M. (2010). Why Wal-Mart wants to take the driver’s seat. Bloomberg Businessweek, 4181, 17–18.

Butler, S. (2013). Tesco accused of squeezing suppliers to support its profits. In: The Guardian (November 28, 2013). Accessed January 13, 2015, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/nov/28/tesco-accused-of-squeezing-suppliers.

Carr, A. S., & Pearson, J. N. (1999). Strategically managed buyer–supplier relationships and performance outcomes. Journal of Operations Management, 17(5), 497–519.

Carter, C. R. (2000). Ethical issues in international buyer–supplier relationships: A dyadic examination. Journal of Operations Management, 18(2), 191–208.

Carter, C. R., & Jennings, M. M. (2004). The role of purchasing in corporate social responsibility: A structual equation analysis. Journal of Business Logistics, 25(1), 145–186.

Carter, J. R., & Narasimhan, R. (1996). Is purchasing really strategic? Journal of Supply Chain Management, 32(1), 20–28.

Casciaro, T., & Piskorski, M. J. (2005). Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(2), 167–199.

Cohen, D. V. (1993). Creating and maintaining ethical work climates: Anomie in the workplace and implications for managing change. Business Ethics Quarterly, 3(4), 343–358.

Cox, A. (1999). Power, value and supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 4(4), 167–175.

Cox, A., Sanderson, J., & Watson, G. (2001a). Supply chains and power regimes: Toward an analytic framework for managing extended networks of buyer and supplier relationships. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 37(2), 28–35.

Cox, A., Sanderson, J., Watson, G., & Lonsdale, C. (2001b). Power regimes: A strategic perspective on the management of business-to-business relationships in supply networks. In: H. Håkansson, C. A. Solberg, L. Huemer, & L. Steigum (Eds.), Proceedings of the 17th Annual IMP Conference: Interactions, Relationships and Networks: Strategic Dimensions, 9–11 September, Norwegian School of Management BI, Oslo.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2007). Business ethics. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Crisp, R. (1995). Deontological ethics. In T. Honderich (Ed.), The Oxford companion to philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crook, T. R., & Combs, J. G. (2007). Sources and consequences of bargaining power in supply chains. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 546–555.

Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Stephens, C. (1989). An ethical weather report: Assessing the organization’s ethical climate. Organizational Dynamics, 18(2), 50–62.

Dahl, R. A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2(3), 201–215.

de Leeuw, S., & Fransoo, J. (2009). Drivers of close supply chain collaboration: One size fits all? International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(7), 720–739.

Devaraj, S., Krajewski, L., & Wei, J. C. (2007). Impact of eBusiness technologies on operational performance: The role of production information integration in the supply shain. Journal of Operations Management, 25(6), 1199–1216.

Dienhart, J. W. (2000). Business, institutions and ethics. A text with cases and readings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Drake, M. J., & Schlachter, J. T. (2008). A virtue-ethics analysis of supply chain collaboration. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 851–864.

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependency relations. American Sociological Review, 27(1), 31–41.

Emiliani, M. (2003). The inevitability of conflict between buyers and sellers. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 8(2), 107–115.

Fassin, Y. (2005). The reasons behind non-ethical behaviour in business and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(3), 265–279.

Fearne, A., Duffy, R., & Hornibrook, S. (2004). Measuring distributive and procedural justice in buyer/supplier relationships: An empirical study of UK supermarket supply chains. In: Proceedings of 88th Seminar, European Association of Agricultural Economics, Paris, 5–6 May.

Feinberg, J. (1988). Harmless wrongdoing: The moral limits of the criminal law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flynn, B. B., Huo, B., & Zhao, X. (2010). The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. Journal of Operations Management, 28(1), 58–71.

Fontrodona, J., & Sison, A. J. G. (2006). The nature of the firm, agency theory and shareholder theory: A critique from philosophical anthropology. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 33–42.

Frederiksen, C. (2010). The relation between policies concerning corporate social responsibility (CSR) and philosophical moral theories—An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(3), 357–371.

Freemann, S. (2012). Original Position. In: E. N. Zalta (Ed.) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Accessed October 01, 2013, available at http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2012/entries/original-position.

French, J. R. P, Jr, & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, 13, 32–33.

Fritzsche, D. J. (2000). Ethical climates and the ethical dimension of decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 24(2), 125–140.

Fritzsche, D. J., & Oz, E. (2007). Personal values’ influence on the ethical dimension of decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 335–343.

Fu, Y., & Piplani, R. (2004). Supply-side collaboration and its value in supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research, 152(1), 281–288.

Gates, D. (2013). McNerney: Boeing will squeeze suppliers and cut jobs. In: The Seattle Times (May 22, 2013). Accessed: July 15, 2014, available at: http://seattletimes.com/html/ .

Golash, D. (1981). Exploitation and coercion. Journal of Value Inquiry, 15(4), 319–328.

Gonzalez-Padron, T., Hult, G. T. M., & Calantone, R. (2008). Exploiting innovative opportunities in global purchasing: An assessment of ethical climate and relationship performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(1), 69–82.

Greenblat, E. (2014a). Coles’ ARC rebate program: Creating unfair pressure. In: The Sydney Morning Herald (May 5, 2014). Accessed: June 30, 2014, available at: http://www.smh.com.au/business/retail/accc-takes-action-against-coles-over-alleged-treatment-of-suppliers-20140505-37rei.html.

Greenblat, E. (2014b). How Coles squeezed suppliers. In: Financial Review (May 5, 2014). Accessed: July 15, 2014, available at: http://www.farmweekly.com.au/news/agriculture/.

Gulati, R., & Sytch, M. (2007). Dependence asymmetry and joint dependence in interorganizational relationships: Effects of embeddedness on a manufacturer’s performance in procurement relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 32–69.

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4), 367–388.

Heide, J. B., & Miner, A. S. (1992). The shadow of the future: Effects of anticipated interaction and frequency of contact on buyer–seller cooperation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(2), 265–291.

Henke, J. W, Jr, Parameswaran, R., & Pisharodi, R. M. (2008). Manufacturer price reduction pressure and supplier relations. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 23(5), 287–300.

Henke, J. W, Jr, Yeniyurt, S., & Zhang, C. (2009). Supplier price concessions: A longitudinal empirical study. Marketing Letters, 20(1), 61–74.

Hibbard, J. D., Kumar, N., & Stern, L. W. (2001). Examing the impact of destructive acts in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), 45–61.

Hingley, M. K. (2005). Power to all our friends? Living with imbalance in supplier–retailer relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(8), 848–858.

Hoejmose, S. U., Grosvold, J., & Millington, A. (2013). Socially responsible supply chains: Power asymmetries and joint dependence. Supply Chain Management, 18(3), 277–291.

Howe, W. S. (1998). Vertical market relations in the UK grocery trade: Analysis and government policy. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 26(6), 212–224.

Ireland, R. D., & Webb, J. W. (2007). A multi-theoretic perspective on trust and power in strategic supply chains. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 482–497.

James, H. S. (2000). Reinforcing ethical decision making through organizational structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(1), 43–58.

Johnson, J. L., Sakano, T., Cote, J. A., & Onzo, N. (1993). The exercise of interfirm power and its repercussions in U.S.–Japanese channel relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(2), 1–10.

Johnston, D. A., McCutcheon, D. M., Stuart, F. I., & Kerwood, H. (2004). Effects of supplier trust on performance of cooperative supplier relationships. Journal of Operations Management, 22(1), 23–38.

Kähkönen, A.-K. (2014). The influence of power position on the depth of collaboration. Supply Chain Management, 19(1), 17–30.

Kaptein, M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2008). The effectiveness of business codes: A critical examination of existing studies and the development of an integrated research model. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(2), 111–127.

Ke, W., Liu, H., Wei, K. K., Gu, J., & Chen, H. (2009). How do mediated and non-mediated power affect electronic supply chain management system adoption? The mediating effects of trust and institutional pressures. Decision Support Systems, 46(4), 839–851.

Kim, K. (2000). On interfirm power, channel climate, and solidarity in industrial distributor–supplier dyads. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(3), 388–405.

Klassen, R. D., & Vereecke, A. (2012). Social issues in supply chains: Capabilities link responsibility, risk (opportunity), and performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 103–115.

Koehn, D. (1992). Toward an ethic of exchange. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(3), 341–355.

Kumar, N. (2005). The power of power in supplier–retailer relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(8), 863–866.

Lawler, E. J., & Yoon, J. (1996). Commitment in exchange relations: Test of a theory of relational cohesion. American Sociological Review, 61(1), 89–108.

Levin, D. P. (1993). G.M. cites requests by Lopez. In: New York Times (May 24, 1993). Accessed May 04, 2013, available at www.nytimes.com/1993/05/24/business/gm-cites-requests-by-lopez.html.

Lindgreen, A., Vanhamme, J., van Raaij, E. M., & Johnston, W. J. (2013). Go configure: The mix of purchasing practices to choose for your supply base. California Management Review, 55(2), 72–96.

Lindgreen, A., & Wynstra, F. (2005). Value in business markets: What do we know? Where are we going? Industrial Marketing Management, 34(7), 732–748.

Locke, E. A. (2006). Business ethics: A way out of the morass. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 324–332.

Locke, E. A., & Woiceshyn, J. (1995). Why businessmen should be honest: The argument from rational egoism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(5), 405–414.

Mabert, V. A., & Venkataramanan, M. (1998). Special research focus on supply chain linkages: Challenges for design and management in the 21st century. Decision Sciences, 29(3), 537–552.

Maitland, I. (2002). The human face of self-interest. Journal of Business Ethics, 38(1), 3–17.

Maloni, M., & Benton, W. (2000). Power influences in the supply chain. Journal of Business Logistics, 21(1), 49–74.

Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2009). Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 71–89.

Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175–194.

Mayer, R. (2007). What’s wrong with exploitation? Journal of Applied Philosophy, 24(2), 137–150.

Micewski, E., & Troy, C. (2007). Business ethics: Deontologically revisited. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(1), 17–25.

Mill, J. S. (2007). Utilitarianism, liberty and representative government. Rockville, MD: Wildside Press.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state and utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Nyaga, G. N., Lynch, D. F., Marshall, D., & Ambrose, E. (2013). Power asymmetry, adaption and collaboration in dyadic relationships involving a powerful partner. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(3), 42–65.

Olekalns, M., & Smith, P. (2009). Mutually dependent: Power, trust, affect and the use of deception in negotiation. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(3), 347–365.

Parsons, W. (2009). Wilkinson squeezes suppliers. DIY Week (18 September, 2009), 1-1.

Poppo, L., & Zenger, T. (2002). Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 707–725.

Pugh, D. S., Hickson, D. J., Hinings, C. R., & Turner, C. (1968). Dimensions of organization structure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 13(1), 65–105.

Quinn, F. J. (1997). What’s the buzz. Logistics Management, 36(2), 43–47.

Quinn, J. B. (2000). Outsourcing innovation: The new engine of growth. Sloan Management Review, 41(4), 13–28.

Rachels, J. (2002). The elements of moral philosophy. New York: McGra-Hill.

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Robertson, D. C., & Rymon, T. (2001). Purchasing agents’ deceptive behavior: A randomized response technique study. Business Ethics Quarterly, 11(3), 455–479.

Rottig, D., Koufteros, X., & Umphress, E. (2011). Formal infrastructure and ethical decision making: An empirical investigation and implications for supply management. Decision Sciences, 42(1), 163–204.