Abstract

We investigate the cross-cultural relationships between spirituality and ethical decision-making in Norway and the U.S. Data were collected from business students (n = 149) at state universities in Norway and the U.S. Results indicate that intention to behave ethically was significantly related to spirituality, national culture, and the influence of peers. Americans were significantly less ethical than Norwegians based on the three dimensions of ethics, yet more spiritual overall. Interestingly, the more spiritual were Norwegians, the more ethical was their decision-making. By contrast, the more spiritual were Americans, the less ethical was their decision-making. The research also found that peer influences were more important to Norwegians than to Americans in making ethical decisions. Finally, spiritual people from the U.S. were more likely to use a universalistic form of justice ethics, as opposed to a more particularistic form of justice ethics used by Norwegians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In light of the recent rise in unethical business conduct, the need to understand the antecedents to ethical decision-making has become more critical. Although many have recognized the impact of the social context or the environment within which an individual makes ethical decisions (Hunt and Vitell 1992; Jones 1991; Robertson and Crittenden 2003; Trevino 1986), the influence of internal factors on ethical decision-making needs further study. In this article, data from Norway and the U.S. are utilized to examine three sources of influence on ethical decision-making, personal spirituality, and peer pressure (which represent two micro-level influences) as well as national culture (a macro-level influence). Taking into account the bombing and mass shooting which occurred on July 24, 2011 in Norway—with the Norwegian suspect claiming both religious and nationalistic motivations for his egregious behavior—an improved understanding of relationships between spirituality and ethical decision-making in Norway may have taken on an increased importance. Examining cross-cultural differences with the U.S. in regards to any relationships may be illuminating in determining the consistency, pervasiveness, and potential relevance of spirituality to business ethics.

Social Identity Theory and Ethical Behavior

To examine the relationship between ethical decision-making and behavioral norms, we use social identity theory (Tajfel 1982; Westerman et al. 2007). According to Stets and Burke (2000), this theory suggests a social identity is “a person’s knowledge that he or she belongs to a social category or group” (p. 225). A social group is a group of individuals who perceive themselves as part of the same social category. Part of the process of social identity formation involves individuals striving to highlight the perceive commonalities between the self and other in-group members. These commonalities include their religion, their families, communities, professions, and nations (Dworkin 1986; Gewirth 1988; Scheffler 2001; Stets and Burke 2000). If an individual were to say, “My faith would not allow me to that,” or “In my country, we wouldn’t do that,” he or she is asserting that behaving in a way contrary to spiritual or country norms and values would weaken one’s social coupling (Charney 2003). As a result, people abstain from tasks seen as incompatible with their identity (Steele et al. 2002).

The Importance of National Culture to Social Identity

Kymlicka asserts that national identity is particularly suited to serving as a primary focus of identification, and it “prioritizes nationalist identity over and above all of the other ‘identities’ that an individual might have and the nation over and above all other possible cites of identity formation” (Charney 2003, p. 301). National identifications have been argued to possess a transcendent quality in that, through national membership, our individual accomplishments take on an additional meaning by becoming part of a continuous creative effort (Tamir 1993). Identifying with one’s country also suggests that our daily activities have meaning in that they fit into a pattern of norms and behaviors which are culturally recognized as appropriate ways of leading one’s life. Thus, national culture plays a major role in determining identity and social referents. Kymlicka (1995) claims that individuals identify so closely with their cultural-national communities that assimilation into other cultures is very difficult: “Cultural membership affects our very sense of personal identity and capacity. The connection between personal identity and cultural membership is suggested by a number of considerations….Why cannot members of a decaying culture simply integrate into another culture?… [B]ecause of the role of cultural membership in people’s self-identity….[N]ational identity…provides a secure foundation of individual autonomy and self-identity” (p. 105). Thus, national membership represents a bond that individuals cannot decouple from and they “regard it as unthinkable to view themselves without” (Rawls 1980, pp. 544–545).

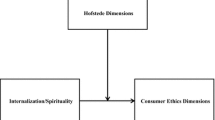

Hofstede’s (1980) cultural dimensions are designed to describe cross-cultural differences in behavior. This study examines the influence of national culture on ethical decision-making by examining two countries (Norway and the U.S.) with significant differences on two cultural dimensions with the potential to have a significant impact on ethical decision-making: masculinity/femininity and individualism/collectivism (see Fig. 1).

The individualism/collectivism cultural dimension varies from individualism on one end to collectivism at the other. Individualism describes the inclination of people to place their own interests and those of their immediate family ahead of the interests of any other stakeholder. By contrast, collectivism describes a culture where people form part of strong, cohesive groups, and care for each other. “We” is important in collectivist cultures (such as Norway) where members tend to safeguard each other’s interests in return for their loyalty. In a highly collectivistic country, decision-makers are looking out for the good of the maximum number of people and are more likely to adhere to macro-level norms (Hofstede 2001); hence, their ethical behavior is likely to more closely reflect their national culture. In an individualistic country like the U.S., it can be expected that decision-makers will be less concerned with achieving outcomes that result in the greatest benefit for the largest number of people, and therefore be more likely to use ethical criteria adopted on a more individual basis.

The second Hofstede (1980) dimension on which the U.S. and Norway are reported to possess significant differences, masculinity/femininity, examines the degree to which a country embraces achievement or nurturing. In a masculine culture, “social gender roles are clearly distinct. Men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and this type of society values material success and achievements, women are supposed to more modest, tender and concerned with the quality of life” Hofstede (2001, p. 297). Thus, masculine cultures (like the U.S.) tend to place importance on ambition, ego, higher pay, and the pursuit of “things.” Femininity “pertains to societies in which social gender roles overlap (i.e., both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender and concerned with the quality of life)”. As indicated by Arrindell et al. (2003), feminine cultures (such as Norway) tend to place importance on people and warm relationships, and the dominant values in society are caring for others and preservation. In a masculine country, it can be expected that decision-makers will be less concerned with achieving outcomes that take into account the needs of others, will therefore be less likely to use ethical criteria adopted from those closest to them, namely their peers, and will emphasize using more self-serving ethical criteria when making decisions. Feminine cultures, with their emphasis on relationships, can be expected to be the exact opposite and more strongly include peers in decision-making (Beekun et al. 2010). It is anticipated that these Hofstede (1980) cultural differences between Norway and the U.S. will have significant effects on ethical decision-making.

Spirituality and Ethics

Another major source of individual values that is increasingly linked to ethical thinking and behavior is spirituality. Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2003) define spirituality as “the individual’s drive to experience transcendence, or a deeper meaning to life, through the way in which they live and work.” Ashmos and Duchon (2000, p. 137) define spirituality at work as “the recognition that employees have an inner life that nourishes and is nourished by meaningful work that takes place in the context of community.” They stress that “spirituality at work is not about religion, although people may sometimes express their religious beliefs at work.” Mitroff and Denton (1999) summarize some key elements of spirituality as follows:

-

Spirituality is “highly individual and intensely personal.”

-

Spirituality revolves around the conviction that “there is a supreme power, a being, a force […] that governs the entire universe.”

-

Our purpose on earth is “to do good.”

-

Spirituality is non-denominational.

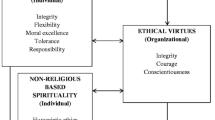

Research has explored this theoretical connection between ethics and spirituality at work (Velasquez 1996; Giacalone and Jurkiewicz 2003), although the empirical research on this relationship is limited to the relationship of work values which have been correlated with spirituality (benevolence (Adams et al. 2006); and integrity (Kouzes and Posner 1995; George et al. 2002)). We focus on three specific ethics dimensions in relating spirituality to ethics: justice, utilitarianism, and relativism.

Justice, Spirituality, and Culture

The justice perspective is oriented to ensure fairness—fair treatment according to ethical or legal standards. It suggests that society imposes rules to protect all individuals from the basic selfish desires of others resulting in tension between the needs of society as a whole and the freedom of the individual. However, as Faver (2004) points out, people of faith perceive justice, especially social justice, as being an integral part of their spirituality, and often use the resources of their religious institutions to provide services and to strive for social change.

While more spiritual people may emphasize justice in their actions at work and elsewhere, the application of justice may not be uniform across national borders. Inhabitants from countries that are high in individualism may be more likely to use a different approach to justice when compared to those from countries that are high in collectivism. Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) have proposed two views of justice: particularistic and universalistic. Particularism suggests that moral standards may be idiosyncratic and may vary among groups within a single culture, among cultures, and over time. Thus, an action’s ethicality is gaged solely on rules, but rather from the personal experiences of individuals and groups. Ascertaining “right” from “wrong” is done in terms of one’s in-group or kinship network (Ting-Tomey 1998). In collectivistic cultures, individuals view themselves as fundamentally and interdependently connected to others, where the self is defined in terms of its relationships with others (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Members of collectivist countries become members of cohesive in-groups from birth onward that protect and support them throughout their lifetimes. As a result, they are more sensitized to their social context, rely on their in-groups to reduce uncertainty, and are more likely to adopt a particularistic form of justice ethics.

Universalism is the reverse of particularism, using objective rules and regulations to separate right from wrong; it tends to be oblivious to idiosyncrasies that obviate rules (Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner 1998). In individualistic and masculine cultures such as the U.S., there is a strong emphasis on individual competitive success, and a reliance on a fair playing field of systems-oriented justice norms that provide rules and procedures for guidance. Thus, when confronted with the same ethical dilemmas, one would expect the Norwegian feminine/collectivists to adopt a particularistic approach, whereas the U.S. masculine/individualists may prefer a universalistic approach.

Utilitarianism, Spirituality, and Culture

As suggested by Velasquez (1996) and Hartman and Desjardins (2008), utilitarianism is a consequentialist approach to ethics. An action is deemed ethical if it is achieves the greatest benefit or “good” for the largest number of people. Given that spiritually oriented people tend to want to help others, one would expect collectivist cultures to accentuate this utilitarian aim even more than individualistic cultures due to their emphasis on caring for others.

Relativism, Spirituality, and Culture

Ethical relativism suggests that “ethical values are relative to particular people, cultures, or times” (Hartman and Desjardins 2008, p. 67). Velasquez (1996, p. 15) defines ethical relativism as “the view that the only standards determining the ethical quality of a particular act or type of act, are the moral norms present in the society within which the act takes place.” Sjöberg (1991, pp. 24–27) suggests that a universal code of ethics may not be practical since because day-to-day ethical decisions are dependent on our cultural background, local customs, and context. Ethical relativism is frequently contrasted with moral absolutism. Moral absolutism contends that moral standards are not relative but absolute and universal whether these involve general moral principles or codes of behavior (El-Astal 2005). As indicated by Husted et al. (1996), a strong case can be made for convergence of managerial values in the face of dubious international business practices. Unlike organized religion’s orthodoxy which is generally founded on absolute and universal principles, one would expect ethical relativism to be positively correlated with spirituality since it is, by definition, nurtured through each person’s personal life and work experiences.

Peers and Ethical Decision-Making

It has been asserted that organizational peers provide the normative structure and serve as the guides for employee decision-making (Schein 1984), and that they set the standards and serve as the referents for behavior within organizations (Jones and Kavanagh 1996). Prior research has demonstrated this important influence of peers in determining an employee’s intention to behave ethically (Westerman et al. 2007). Overall, peers have a greater influence on employees’ ethical behavior than managers (Keith et al. 2003; Zey-Ferrell et al. 1979). Physical proximity and frequency of direct physical contact have been shown to be primary predictors of comparative referents (Gartrell 1982) which are used for ethical decisions. The enhanced reliance on in-groups and personal relationships for ethical decision-making in collectivistic and feminine cultures leads us to believe that Norwegians will rely more on their peers for ethical judgments. In contrast, masculine and individualistic U.S. decision-makers, with an emphasis on objectivistic system-oriented justice norms are less likely to be influenced by peers in ethical decision-making. Thus, in addition to our focus on national culture and spirituality as sources of influence on ethical decision-making, our research examines the influence of one’s peers to determine their relative impact on an employee’s ethical decision-making, and whether national culture plays a role in this relationship.

Based on the above discussion, we suggest the following hypotheses:

H1

There is a relationship between intention to behave ethically and spirituality, national culture and peer pressure.

H2

Choice of ethical criteria will be a function of the degree of spirituality and national culture:

H2.a

Spiritual people from a masculine and individualistic culture will use universalistic justice when faced with an ethical dilemma.

H2.b

Spiritual people from a feminine and collective culture will use particularistic justice when faced with an ethical dilemma.

H3

Acceptance of peer pressure will be a function of the degree of spirituality and national culture:

H3.a

Spiritual people from a masculine and/or individualistic culture will be less likely to yield to peer pressure when faced with an ethical dilemma.

H3.b

Spiritual people from a feminine and/or collective culture will be more likely to yield to peer pressure when faced with an ethical dilemma.

To test these hypotheses, we have chosen two countries (The U.S. and Norway) representing different quadrants of the individualism/collectivism and masculinity graphic plot (Hofstede 1980) (see Fig. 1). As indicated in Fig. 1, Norway represents a collectivistic, feminine culture. Respondents from this culture would be expected to rely on (a) criteria based on a particularistic approach to justice (Hypothesis 2b), utilitarianism and relativism (Hypothesis 1), and (b) to use peers as their primary referents for ethical decision-making behavior (Hypothesis 3b). The U.S. represents the opposite quadrant, an individualistic, masculine culture in which we would expect respondents to rely on (a) criteria based on a universalistic approach (Hypothesis 2a) to justice, utilitarianism, and relativism (Hypothesis 1), and (b) to use peers relatively less as their primary referents for ethical decision-making behavior (Hypothesis 3a).

Methodology

Sample

Data were collected from a convenience sample of respondents (116 from Norway, 33 from the U.S.) who were invited to participate as a result of enrollment in selected classes. The participants included graduate business students at universities located in the two countries. Graduate business students were included because they are a commonly used proxy for business people and have been found in prior research to share a high degree of congruence with business professionals (Dubinsky and Rudelius 1980). Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the complete data set.

Measurement of Countries along Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

We utilized the two subdimensions of Hofstede’s (1980) measure of cultural differences that were the most divergent between Norway and the U.S. and relevant to the hypotheses in our study (individualism/collectivism and masculinity/femininity). In his seminal study involving 116,000 respondents, Hofstede (1980) classified over 70 countries along the key cultural dimensions utilized in our study. In addition, questionnaires to gather data to measure these cultural dimensions can be obtained from Hofstede in many languages.

Measurement of Peer Pressure and of Ethics Dimensions

The instrument used is Reidenbach and Robin’s (1988, 1990) and Cohen et al.’s (1996) multi-scenario, multi-item survey. This multi-criteria instrument presents the respondent with a set of three scenarios each involving an ethical dilemma, and asks a number of questions to determine whether the respondent or his/her peers will behave in the same manner as the character in the scenario. The scale used to assess intention to behave ranges from 1 to 7, but is reverse coded. Thus, a higher score means that the respondent believes that he or his/her peers would be less likely to behave in the same manner as the character in each scenario; in other words, a higher score would indicate more ethical behavior on behalf of the respondent or his/her peers. Table 2 shows the three scenarios used to assess intention to behave.

The instrument was translated into Norwegian and back-translated back into English to verify for content and understanding. The Norwegian respondents were proficient in English as they were taking their graduate business classes in English and completed the English version of the questionnaire.

Second, using the above scenarios, the questionnaire allowed for the measuring of three ethical perspectives or areas of moral philosophy: justice, utilitarianism, and relativism. The seven-point bipolar scales for measuring these three dimensions are described in Table 3.

Measurement of Spirituality

The Human Spirituality Scale (HSS) (Wheat 1991) was used to gage the degree of individual spirituality, and has been validated previously by Belaire and Young (2000). The Cronbach Alpha coefficient for the HSS is 0.89 (Wheat 1991), and was calculated as 0.83 in our study. This instrument contains 20 Likert-scaled items with the scale ranging from 1 (constantly) to 5 (never) for each item. Respondent scores are calculated by adding the ratings across all 20 items, and can range from 20 to 100. The respondent scores were rescaled so that the higher the respondent’s score on the HSS, the more personally spiritually he/she is.

Model

The model in our study was comprised of the following:

-

1)

Three dependent variables representing the three/ethical dimensions of justice, utilitarianism, and relativism.

-

2)

Four independent variables representing the expected behavior of peers (PEER), the degree to which the respondent conformed to Hofstede’s two dimensions of national culture (INDIVIDUALISM and MASCULINITY), and the level of spirituality of the individual.

-

3)

A control variable for the type of scenario used in the survey instrument. As shown in Table 2, three types of scenarios are used in this study. Prior research (Reidenbach and Robin 1988) also indicates that judgments may depend on the setting in which they occur.

Results

Table 4 summarizes of the descriptive statistics. In general, Americans were less ethical than Norwegians based on the three dimensions of ethics, they were less likely to be susceptible to peer pressure, and they were more masculine, and more spiritual.

Table 5 summarize the correlations across all three scenarios for each country. In general, the more feminine Norwegians were, the more spiritual they were (r = −.27, p < .001). Surprisingly, the more individualistic Norwegians were, the more spiritual they were (r = .21, p < .01). The more spiritual Norwegians were, the more they found the decisions in the three ethical scenarios to be less ethical based on utilitarianism (r = .29, p < .001), justice (r = .18, p < .01), and relativism (r = .19, p < .001), and the more susceptible they were to peer pressure (r = .29, p < .001).

Similarly, the more feminine were Americans, the more they were spiritual (r = −.25, p < .05). However, spirituality and individualism were not significantly correlated for them. In contrast to the Norwegians, the less spiritual were Americans, the less ethical they found the decisions in the three ethical scenarios based on utilitarianism (r = −.29, p < .01), justice (r = −.27, p < .01), and relativism (r = −.29, p < .01), and the less susceptible they were to peer pressure. As we will see in the “Discussion” section, this may be due to the fact spirituality may hold a different meaning for Norwegians as compared to Americans.

Hypothesis 1 was largely supported through repeated measures MANOVA analysis: respondents’ decision to behave ethically was a function of spirituality, national culture (masculinity/femininity), and peer pressure. Consistent significant results were reported for justice, utilitarianism, and relativism for spirituality, national culture, and peer pressure (Table 6).

The choice of ethical criteria (justice) was a function of multiple variables (p 6,367 = 17.92, p < .0001, r 2 = 0.23) with several independent variables being significant: spirituality (F 1,367 = 12.05, p < .001), peer pressure (F 1,367 = 64.06, p < .0001), and masculinity (F 1, 367 = 27.37, p < .001). Utilitarianism was also a function of multiple variables (p 6,367 = 14.19, p < .0001, r 2 = .191) with several independent variables being significant: spirituality (F 1,367 = 4.95, p < .05), peer pressure (F 1,367 = 63.96, p < .0001), and masculinity (F 1,367 = 10.69, p < .01). Finally, relativism is a function of multiple variables (F 6,367 = 24.06, p < .0001, r 2 = .29) with several independent variables being significant: spirituality (F 1,367 = 13.79, p < .001), peer pressure (F 1,367 = 100.77, p < .0001), and masculinity (F 1,367 = 15.29, p < .001).

Hypothesis 2 was supported through the separate MANOVAs conducted for the U.S. and for Norway—as summarized in Tables 7 and 8. As can be seen in Table 7, justice in the U.S. is a function of spirituality without the influence of peers or of national culture (individualism and masculinity) (F 6, 91 = 4.61, p < .001). This result provides support for Hypothesis 2.a. By contrast, Table 8 indicates that justice in Norway is a function of spirituality and is subject to the influence of peers and both national culture dimensions (individualism/collectivism and masculinity/femininity) (F 6,275 = 15.18, p < .0001). This supports Hypothesis 2.b.

Hypothesis 3 also received partial support. Hypothesis 3.a was not supported whereas Hypothesis 3.b was supported. As seen in Table 7, it would seem that respondents from an individualistic and masculine culture such as the U.S. are influenced by peers when engaged in ethical decision-making (except with respect to justice). By contrast, respondents from a collective and feminine culture such as Norway are very much influenced by peers with respect to all three ethical dimensions when dealing with ethical dilemmas (as indicated in Table 8). That Norwegians are overall more susceptible to peer influence than Americans is also confirmed in Table 9 where a t test indicates that Norwegians are more influenced by peers than Americans (t = −7.5, p < .0001). Finally, Table 9 indicates that Americans may be more spiritual (t = 4.1, p < .0001) and more masculine than Norwegians (t = 5.99, p < .0001). Interestingly, Americans and Norwegians in our sample did not differ significantly in the individualism/collectivism dimension.

Discussion

Our goal in this study was to shed some light on the relationships between three fundamental variables in human existence: ethics, spirituality, and national culture. Our hypotheses were generally supported by the data, indicating a complexity between these influences. Results indicated that intention to behave ethically was significantly related to spirituality, national culture, and the influence of peers. Thus, spirituality alone does not determine ethical behavior—the results of this research indicate that we must take into account the simultaneous impact of peer pressure and national culture. We also found that spiritual people from the U.S. were more likely to use a universalistic form of justice ethics, as opposed to the more particularistic form of justice ethics used by Norwegians. Further, peer influences were more significant to Norwegians than to Americans in making ethical decisions. Finally, our results indicated that Americans were significantly less ethical than Norwegians based on the three dimensions of ethics, yet more spiritual overall.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing results was that the relationship between spirituality and business ethics was opposite for Norwegians and Americans. The data from this study indicated that the more spiritual were Norwegians, the more ethical was their decision-making. In contrast, the more spiritual were Americans, the less ethical was their decision-making. The contradictory results may be due to the fact that spirituality may mean different things for Norwegians as compared to Americans. We can only speculate as to the reasons. Milliman et al. (2003) noted that spirituality emphasizes connectedness and the needs of the many before the needs of the one. It is possible that more spiritual Americans do not share this understanding or definition of spirituality. In the U.S., spirituality has become increasingly intertwined with national politics, which may be altering how spirituality is perceived by Americans. In a recent study of religion and politics, the Pew Research Center (2011) concluded that for the 2008 U.S. Presidential election “Religion remained a very strong predictor of voters’ choices,” and a logistic regression analysis confirmed that “church attendance was a very strong predictor of how people voted in 2008, even after taking into account other demographic factors, such as race, age, gender, education, income, urban/rural status, region and union membership. Holding these other factors constant, the probability that a voter who attends religious services at least weekly cast his ballot for Obama was 37 out of 100 (.37).” Further evidence of this enhanced relationship is indicated by the fact that George W. Bush was the first U.S. President to host events for a National Day of Prayer every year when he was in office.

Mirriam-Webster (2011) notes two definitions of the word “politics” of relevance to this conjecture: (1): “competition between competing interest groups or individuals for power and leadership (as in a government)”; and (2) “political activities characterized by artful and often dishonest practices.” If there exists an increasing conflation between politics and religion in the U.S., it is possible that the sense of community that is critical to enhancing spirituality and the needs of the many over the needs of the few may be weakened, replaced by a more political definition as a means of expressing competitive and potentially divisive political thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. Further, the results of this study indicated opposite results in terms of the relationship between peer pressure and business ethics. More ethical Norwegians were influenced by peer pressure, whereas more ethical Americans resisted peer influence. As spirituality in practice has social and community-building aspects with an intrinsic reliance on peer influence, it may provide further support for the concerns regarding potential interrelationships between religion, politics, and reduced business ethics in the U.S.

We want to again emphasize that this is speculative. As religious values and beliefs can exert a profound influence on human behavior and codes of ethics, an enhanced understanding of the social or intrapersonal mechanisms underlying the relationship between enhanced spirituality and reduced American business ethics represents fertile ground for future research. For example, it is not uncommon in the U.S. for an individual to reference God as a primary role model for their behavior. Future research could focus on developing a better understanding of why spiritual people seem more willing to commit ethical violations in a business setting in the U.S., while others can be persuaded in the appropriate direction by peers, norms, or organizational culture. The recognition of the important cross-cultural differences in these relationships may present opportunities for enhanced personal and interpersonal awareness, behavioral interventions, or training and development on appropriate business ethical norms.

Perhaps leadership in organizations may play an important role in linking ethics and spirituality in a consistently more constructive direction. For example, “transformational leadership” is rooted in the ability of leaders to inspire followers to transcend their own self-interests for the good of the organization, and such transformational leaders are described as being capable of having a profound and extraordinary effect on their followers (Bass et al. 2003). Servant leadership (Greenleaf 1977) is inspired partly by the story of Jesus washing the feet of his Apostles, and combines the idea of service with leadership. The leader is to serve the needs of his/her followers before taking care of his/her own needs, and is to help them become “better servants” themselves. Socialized charismatic leadership (Brown and Trevino 2006) conveys values that are other-centered (as opposed to self-centered) and is represented by leaders who model ethical conduct. These leadership theories focus on inspiring followers and transcendence, possess foundations built on ethical leadership, and seem to share commonalities with spirituality. As such, they represent an additional area for future study.

A significant limitation of this study is that the sample population consisted of students. A specific focus on surveying employees may result in a stronger analysis of the relationships. However, since today’s students are tomorrow’s employees, using a student population is beneficial in determining forthcoming workplace issues. One further caveat in interpreting the results of this study has to do with the difference in the sample sizes of Norwegian and U.S. students. However, care was taken to control for this potential problem statistically by using Type III SS in our analyses.

References

Adams, G., Balfour, D., & Reed, G. (2006). Abu Ghraib, administrative evil, and moral inversion: The value of “putting cruelty first. Public Administration Review, 66(5), 680–693.

Arrindell, W. A., Eisemann, M., Richter, J., Oei, T. P. S., Caballo, V. E., Van der Ende, J., et al. (2003). Masculinity–femininity as a national characteristic and its relationship with national agoraphobic fear levels: Fodor’s sex role hypothesis revitalized. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(7), 795–807.

Ashmos, D. P., & Duchon, D. (2000). Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. Journal of Management Inquiry, 9(2), 134–145.

Bass, B. M., Avolio, B. J., Jung, D. I., & Berson, Y. (2003). Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 207–218.

Beekun, R. I., Stedham, Y., Westerman, J. W., & Yamamura, J. (2010). Effects of justice and utilitarianism on ethical decision making: A cross-cultural examination of gender similarities and differences. Business Ethics: A European Review, 19(4), 309–325.

Belaire, C., & Young, J. (2000). Influences of spirituality on counselor selection. Counseling & Values, 44(3), 189–197.

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Socialized charismatic leadership, values congruence, and deviance in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 954–962.

Charney, E. (2003). Identity and liberal nationalism. American Political Science Review, 97(2), 295–310.

Cohen, J., Pant, L., & Sharp, D. (1996). A methodological note on cross-cultural accounting ethics research. International Journal of Accounting, 31(1), 55–66.

Dubinsky, A. & Rudelius, W. (1980). Ethical beliefs: How students compare with industrial salespeople. In Proceedings of the American Marketing Association Educators Conference (pp. 73–76), Chicago, IL: AMA.

Dworkin, R. (1986). Law’s empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

El-Astal, M. A. S. (2005). Culture influence on educational public relations officers’ ethical judgments: A cross-national study. Public Relations Review, 31, 362–375.

Faver, C. A. (2004). Relational spirituality and social caregiving. Social Work, 49(2), 241–249.

Gartrell, D. C. (1982). On the visibility of wage referents. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 7, 117–143.

George, L. K., Ellison, C., & Larson, D. (2002). Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 190–200.

Gewirth, A. (1988). Ethical universalism and particularism. Journal of Philosophy, 85(3), 283–302.

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2003). Toward a science of workplace spirituality. In R. A. Giacalone & C. L. Jurkiewicz (Eds.), Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance (pp. 3–28). New York: M. E. Shar.

Greenleaf, R. (1977). Servant Leadership. New York, NY: Paulist Press.

Hartman, L., & Desjardins, J. J. (2008). Business ethics: Decision-making for personal integrity and social responsibility. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1992). The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In J. Quelch & C. Smith (Eds.), Ethics in marketing. Chicago, IL: Irwin.

Husted, B., Dozier, J., McMahon, J., & Kattan, M. (1996). The impact of cross-cultural carriers of business ethics on attitudes about questionable practices and form of moral reasoning. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(2), 391–411.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Jones, G. E., & Kavanagh, M. J. (1996). An experimental examination of the effects of individual and situational factors on unethical behavioral intentions in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 15, 511–523.

Keith, N. K., Pettijohn, C. E., & Burnett, M. S. (2003). An empirical evaluation of the effect of peer and managerial ethical behaviors and the ethical predispositions of prospective advertising employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 48, 251–265.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (1995). The leadership challenge: How to keep getting extraordinary things done in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kymlicka, W. (1995). Multicultural citizenship. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change, 16, 426–447.

Mirriam-Webster (2011). Online dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/politics.

Mitroff, I., & Denton, E. A. (1999). A spiritual audit of corporate America. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pew Research Center (2011). Much hope, modest change for democrats: Religion in the 2008 Presidential election. http://www.pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/Much-Hope-Modest-Change-for-Democrats-Religion-in-the-2008-Presidential-Election.aspx.

Rawls, J. (1980). Kantian constructivism in moral theory. Journal of Philosophy, 77(9), 515–572.

Reidenbach, R., & Robin, D. (1988). Some initial steps towards improving the measurement of ethical evaluations of marketing activities. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(11), 871–879.

Reidenbach, R., & Robin, D. (1990). Toward the development of a multidimensional scale for improving evaluations of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(8), 639–653.

Robertson, C. J., & Crittenden, W. F. (2003). Mapping moral philosophies: Strategic implications for multinational firms. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 385–392.

Scheffler, S. (2001). Boundaries and allegiances. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schein, E. H. (1984). Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. Sloan Management Review, 25, 3–16.

Sjöberg, G. (1991). Law and ethics of public relations. International Public Relations Review, 14(1), 24–27.

Steele, C., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Stereotype threat, intellectual identification, and academic performance of women and minorities. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). New York: Academic Press.

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Tamir, Y. (1993). Liberal nationalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton, University Press.

Ting-Tomey, S. (1998). Communicating across cultures. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person-situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Velasquez, M. (1996). Ethical relativism and the international business manager. In F. Neil Brady (Ed.), Ethical universals in international business. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Westerman, J. W., Beekun, R. I., Stedham, Y., & Yamamura, J. (2007). Peers versus national culture: An analysis of antecedents to ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(3), 239–252.

Wheat, L. W. (1991). Development of a scale for the measurement of human spirituality. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. College Park: University of Maryland.

Zey-Ferrell, M., Weaver, K. M., & Ferrell, O. C. (1979). Predicting unethical behavior among marketing practitioners. Human Relations, 32, 557–569.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study has been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 declaration of Helsinki. All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beekun, R.I., Westerman, J.W. Spirituality and national culture as antecedents to ethical decision-making: a comparison between the United States and Norway. J Bus Ethics 110, 33–44 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1145-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1145-x