Abstract

We investigate the nature of the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate financial performance (CFP) by examining how it changes across a third dimension that accounts for firm-specific factors. We propose a semi-latent specification of an endogenous control variable, which can, for the first time, explicitly identify, for each individual firm, the threshold level where the marginal impact of CSR on CFP turns positive. We provide empirical evidence that this threshold depends on the additional dimension and consequently, the previously reported U-shape seems to be an aggregation of relationships of differential magnitude and direction. This disaggregation fits the data better and therefore, we maintain that the addition of a higher dimension, along with the identification of the threshold level, can explain the conflicting results in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

“Does it pay to be good?” (Trudel and Cotte 2009). This question refers to the marginal impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on corporate financial performance (CFP). The initial response of the literature provides a full spectrum of arguments that range from a positive (Jones 1995) to negative (Aupperle et al. 1985) relationship. These inconclusive propositions have led to the realization that CSR might not always be profitable and therefore, a more appropriate question is not “whether”, but “under what conditions” does it pay to be good (Rowley and Berman 2000). Driven by the absence of a strictly monotonic CSR–CFP relationship, several studies suggest that these conflicting results can be attributed to an endogenous (Waddock and Graves 1997) or an asymmetric (e.g., Barnett 2007) relationship. This modelling of higher degrees of variation suggests that a binary approach might be limiting in capturing the complexity of the CSR–CFP nexus (Crane et al. 2018) and implicitly assumes that there might be another level of interaction, governed by observable or unobservable factors.

Addressing this concern, a branch of literature suggests the existence of observable ‘mediators’ (e.g., Saeidi et al. 2015) or ‘moderators’ (e.g., Gully et al. 2013), or in a wider scope multiple criteria (e.g., Lamata et al. 2018) or different ‘management recipes’ (e.g., Isaksson and Woodside 2016), which might affect the way CSR interacts with CFP. They recognize explicitly that the exact relationship might also depend on other factors, but their approach focuses on identifying whether they might affect (magnitude) the CSR–CFP relationship rather than what this relationship might look like (shape). Other studies try to describe the shape of the CSR–CFP link by considering the existence of non-linearities that might arise due to the interaction with latent (unobservable) factors, such as the ability of the firm to interact with its stakeholders (Barnett 2007) or the ambiguity about the quality of a project (Flammer 2015). Because these latent factors cannot be identified/measured, the modelling needs to explicitly describe the shape of the CSR–CFP link by imposing a structural form, usually a quadratic function, on CFP. Consequently, the literature operates under an implicit trade-off between the functional form (shape) and the interacting factor (latent/observable).

We directly address this trade-off by introducing an additional dimension, which accounts for firm specific factors, to the CSR–CFP relationship, and we explicitly model how this dimension might affect its shape. This way, we can, for the first time, identify for each individual firm the exact minimum level (threshold) of CSR required for its impact on CFP to turn positive and thus, the shape of the curvature at firm-specific (rather than at sample) level.

We conduct a global empirical analysis which suggests that the previously reported U-shape cannot be unconditionally applied to all firms. In contrast, we report that the threshold value depends on a third dimension and therefore, we describe, for the first time, the exact intensity of curvature at a firm-specific, rather than at a sample, level. Consequently, we maintain that the overall U-shaped CSR–CFP link is observed across sample due to an aggregation of differently shaped links across a higher dimension. The identification for the inflection point is robust to alternative control variables, as well as to measurement/functional form/cross-sectional differences. Consequently, our approach can explain previously conflicting results that arise due to sampling, because it focuses on a more fundamental (firm-specific) level.

2 Nature of the CSR–CFP relationship

“Doing good and doing well” (Avi-Yonah 2005) or “Does it pay to be good?” (Trudel and Cotte 2009) are two versions of the same question that literature has been concerned with over the last half a century, referring to whether the marginal impact of CSR on CFP can be positive.

2.1 Endogeneity

Early approaches, driven by the shareholder theory (e.g., Friedman 1970) see CSR as a “donation” and thus as a wealth transfer from shareholders to a larger group of stakeholders. This leads to diminishing wealth and to increasing agency problems (e.g. Jensen and Meckling 1976). Consequently, early literature suggests a negative impact of CSR on CFP (Aupperle et al. 1985). In contrast, a stakeholder theory-related approach (Freeman 1984) suggests that social externalities could be traced back to the firm; therefore, they could affect shareholders’ wealth (Agle et al. 2008). Consequently, the goal of a firm that actively tries to better meet its stakeholders’ needs is to increase its shareholders’ wealth (e.g., Jones 1995); thus, the impact of CSR on CFP should be positive (e.g., Li et al. 2018). Empirical and theoretical literature confirms the positive link and attributes this to factors such as enhanced morale, efficiency, and/or productivity (Solomon and Hanson 1985; Barney 1991; Russo and Fouts 1997; Porter and Kramer 2006).

Trying to reconcile these two opposing views, several studies focus on the direction of the relationship and potential endogeneity. Relevant literature reports that companies with higher CFP tend to invest more in CSR (Hillman and Keim 2001; Orlitzky et al. 2003); therefore, no safe conclusion can be reached unless the reverse causality is also addressed. Endogeneity is very relevant in our study because its existence would explicitly challenge the “universal” character of the CSR–CFP relationship. This is also consistent with the propositions of Bénabou and Tirole (2010) who argue that the existence of endogeneity makes inference almost impossible. They even suggest that if endogeneity is quantitatively treated, primarily with instrumental variables (e.g., Shahzad and Sharfman 2017), the intensity of the link is significantly diminished (e.g., Waddock and Graves 1997; Garcia-Castro et al. 2010). We explicitly recognize the importance of endogeneity and suggest a structural equation approach that lets the data identify the existence and magnitude of endogeneity. This approach does not simply address endogeneity by simply “treating” the data, it explicitly models it allowing the data to identify and measure it.

2.2 Asymmetry

Other studies attribute the differences to asymmetries. Brammer and Millington (2008) propose that the positive association between CSR and CFP follows diminishing and decreasing returns. Consequently, if the scope of social responsibility participation strays beyond management in addressing social concerns (e.g., with little or no effect on stakeholders), the net effect is likely to be declining financial performance. They also argue that the correlation between CSR and performance is highest at the extremes, showing that financial performance is high at both very high and very low CSR levels. Barnett (2007) argues that the U-shaped relationship depends on the firm’s ability to “better meet” stakeholders’ needs and thus capitalize on CSR investments, a concept referred to as Stakeholder Influence Capacity (SIC). Barnett and Salomon (2012) report that firms with low/high CSR exhibit higher CFP than firms with moderate CSR. Along the same lines, Flammer (2015) and Flammer and Bansal (2017) identify the existence of threshold effects due to ambiguity. Using a discontinuity approach, marginal CSR investments in the sense that there is increased ambiguity about their future outcome as it is reflected on a “close-call” acceptance/rejection, are found to be significantly different from their decreased ambiguity counterparts. These studies explicitly suggests that not all CSR projects should be expected to have a monotonic impact on CFP, indicating an optimal CSR intensity (e.g., Jawahar et al. 2015) or else a threshold/inflection point (e.g., Barnett and Salomon 2012) where the marginal impact of CSR on CFP changes. Our approach enables a data-driven identification of the shape and magnitude of these asymmetries, as well as of the exact inflection point at a firm-specific level.

2.3 Additional dimension

This asymmetry, attributed mostly to latent (unobservable) underlying factors (e.g., SIC or ambiguity), involves various aspects that are of relevance to our study. First, it recognizes explicitly that the intensity and shape of the CSR–CFP link might depend on other factors. This resonates with the view of other studies (Galbreath and Shum 2012) suggesting that the CSR–CFP relationship is determined by mediators or moderators, such as customer satisfaction, reputation, and competitive advantage (e.g., Walsh and Beatty 2007), or even the capital structure (e.g., Cornett et al. 2016), or a combination of them (e.g., Lamata et al. 2018) into a ‘managerial recipe’ (e.g., Isaksson and Woodside 2016). The ‘mediators/moderators/multi-criteria’ approach investigates the CSR–CFP link beyond a binary context but focuses only on identifying whether one or more observable factors affect the CSR–CFP link without addressing its shape or its magnitude. In contrast, other studies employ unobservable factors, such as SIC (Barnett 2007) or “ambiguity” (Flammer 2015) in order to encompass a multitude of interacting factors, but because of the inability to measure them, they need to imply a functional form—mostly quadratic (Barnett and Salomon 2012) or with threshold effects (Flammer and Bansal 2017). This approach might be prone to misspecification error, while it is also invariant across the underlying factor.

Second, if a factor makes the CSR–CFP link to follow a pattern, then the intensity of a CSR strategy should also depend on this factor. For example, Barnett (2007) suggests that a more intense CSR strategy should be preferred when SIC is high, and vice versa. However, the literature implies a trade-off between identifying either the interacting factor or how it affects the CSR–CFP link (functional form), therefore, it cannot be empirically tested on a firm level.

We recognize that the CSR–CFP link should be examined beyond the binary nexus and that an explicit modelling of a third dimension is necessary to capture the complexity of the relationship. We propose a structural modelling of the additional dimension as an observable endogenous variable, with which we can identify uniquely per firm the threshold level at which the impact of CSR performance on CFP turns positive.

2.4 Reflections on previous literature

Collectively, previous literature on the CSR–CFP link has evolved from approaching the impact of CSR on CFP as a one-dimensional binary problem to accepting that it is a multidimensional issue with distinct sampling properties. There seems to be a consensus on the fact not all CSR activities are profitable and, therefore, different samples exhibit different shapes and magnitude of the CSR–CFP link. Previous studies that try to explain these differences attribute them to potential endogenous and asymmetric effects. More recent literature, which follows a more intensive quantitative approach (e.g., Crane et al. 2018), attempts to model these asymmetries and account for the endogeneity, but we understand that it operates under a significant trade-off; either explicitly defining how the relationship between CSR on CFP looks like, i.e., describing precisely its structural form, or considering that it is governed by latent factors. Consequently, previous models define either the factors or the structural form, but not both.

We purport that this trade-off might be the reason why several empirical studies exhibit cross-sectional differences and report conflicting results. We extend previous literature by addressing this trade-off directly. We do so by proposing a new modelling that investigates potential endogeneity and asymmetries in data driven way, without a pre-specification of the structural form. This is done by introducing and modelling an (extendable) additional dimension, the magnitude of which affects the shape and the magnitude of the CSR–CFP link. Different levels of the additional dimension exhibit a different degree of endogeneity and asymmetry, varying from high convexity to high concavity. Each firm operates at a particular level of the additional dimension, which is linked to a particular shape of the CSR–CFP link (i.e., degree of curvature/concavity). Consequently, our model can estimate the exact degree of curvature of the CSR–CFP relationship at a firm, rather than at an aggregate level. Previous studies present cross-sectional results aiming at describing the overall shape of the CSR–CFP relationship. We decompose this cross-sectional estimate across a third dimension, which explicitly models how this overall/cross-sectional relationship, reported in previous studies, is composed from each individual firm.

We consider this shift from an aggregate level to a firm specific estimate as our major contribution that has the potential to capture various stylized factors (e.g., Bass and Milosevic 2018) in a more unified context and thus, explain the conflicting findings in the literature. The empirical literature reports regional (Shahzad and Sharfman 2017) or cross-sectional (Rowley and Berman 2000) inconsistencies, which, we suggest, emerge from inability to identify the shape of the CSR–CFP link on a firm level. Our approach shifts the focus from a general/universal modelling to a more granular one, where cross-sectional differences—captured by the intensity of the additional dimension—are treated as a determinant of its shape, rather than as inconsistencies.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data

In our analysis we employ three different datasets to investigate the relationship between CSR and CFP, especially focusing on a potentially higher order interaction. First, we employ a primary sample with global coverage, based on “Vigeo” CSR rating, to test whether an additional, observable, dimension can adequately capture different cross-sectional/regional differences.Footnote 1 In addition, we employ two secondary samples for testing the robustness of our findings to different sampling properties and CSR valuation methods. They are based on the constituents of the S&P1500 and S&P500 index with valid data for two periods; 1997–2010 (pre-2010) and 2011–2017 (post-2010), using the “KLD” (pre-2010) CSR rating and the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG; post-2010) performance index provided by Bloomberg, respectively.Footnote 2 For more information please refer to the Online Appendix.

The primary dataset employed consists of all firms rated by “Vigeo” between 1997 and 2012, according to their CSR performance. Vigeo provides CSR performance scores \(0 \le H_{m} \le 100\) on six domains, \(m = 1, \ldots ,M = 6\), which are used to construct a weighted score \(CSR = \frac{1}{100 \times M}\sum\nolimits_{m = 1}^{M} {H_{m} }\), equivalent to their net social performance (Chatterji et al. 2009).Footnote 3

We cleaned the data by dropping all observations reporting negative equity capital. To match financial data with CSR information, only the most up-to-date annual ratings were considered. Furthermore, all observations outside a 5σ-confidence interval were considered outliers and thus omitted. This results in a pooled dataset with a total of 7032 firm-year observations. We split the sample into three broad regional sub-samples, namely the United States (US), Europe (EU), and Rest of the World (ROW), implicitly assuming different market-stylized factors, such as market maturity and risk. To account for industry-specific effects, we use the Thomson Reuters (EIKON) classification, which is also the source for financial firm-specific data.

In order to address previous concerns regarding CSR measurement (Carroll et al. 2016), we test the robustness of our methodology on the KLD data and the ESG disclosure index provided by Bloomberg.Footnote 4 In addition to the Vigeo dataset, we employ a second sample that consists of all firms included in the S&P1500 index with valid observations between 1997 and 2010 and add the corresponding KLD data and industry codes to the sample.Footnote 5 We aggregate the strengths and weaknesses of each firm to create its net social performance score (Barnett and Salomon 2012). KLD rates the firms based on 13 individual social performance criteria and the scores given are + 1 for a strength and − 1 for a weakness/concerns. The score is computed as \(CSR_{it} = \sum\nolimits_{m = 1}^{n} K LD_{mit}\), where \(KLD_{m}\) is the score (− 1 or + 1) of category m and its range is from − 12 to 15. We apply the same data thinning process, which results in a pooled dataset of 10,866 firm-year observations.

Finally, in order to test the robustness of our findings to a different CSR score, as well as to intertemporal differences, we employ a third (final) dataset, which consist of all firms of the S&P500 index with valid observations between 2011 and 2017 and add the corresponding ESG data and industry codes to the sample. Bloomberg reports an aggregated ESG score with a range from 0 to 100 and we compute our CSR score as \(CSR_{it} = ESG_{it} /100\). We apply the same data thinning process, which results in a pooled dataset of 3060 firm-year observations.

3.2 Model

The proposed model can be summarized in the following system of simultaneous equations:

where \(A = \left( {a_{1} , \ldots , a_{q} } \right)\), \(B = \left( {\beta_{1} , \ldots , \beta_{q} } \right)\), \(\Gamma = \left( {\gamma_{0} , \gamma_{1} } \right)\), and \(U = \left( {\mu_{1} , \ldots , \mu_{q} } \right)\) are vectors of parameters to be estimated, and \(p = \left( {Industry,Country,Year} \right)\) is a vector of dummy variables identifying a firm \(i = 1, 2, \ldots ,n\) at time t.Footnote 6\(CFP_{it}\) is the corporate financial performance, captured by return on equity, \(ROE_{it} = Net Income_{i,t} /Equity_{i,t}\). \(Z_{it}\) is how we introduce an additional dimension in the form of a potentially endogenous variable. Z is an observable variable, whose specification is modelled in Eq. (3). However, it appears in Eqs. (1) and (2) as a semi-latent specification (Lewbel 1998) and this way it can indirectly capture other firm specific factors. This is how our study tries to bridge the trade-off between functional form [Eq. (1)] and identification of the interacting variable [Eq. (3)].

Furthermore, Eq. (1) investigates a potential asymmetric impact of CSR on CFP. Coefficient \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}}\) captures the impact of CSR on CFP and is dissected into two regimes: high and low, per Eq. (4) which is a logistic smooth transition function (Chan and Tong 1986; Van Dijk et al. 2002) with a fixed smoothness parameter (i.e., equal to 1):

where \(a_{2}^{low}\) (\(a_{2}^{high}\)) captures the marginal impact of CSR on CFP, when \(CSR_{it} < s_{it}\) (\(CSR_{it} > s_{it}\)). If they are different and statistically significant, this would indicate that the impact of CSR on CFP is different when CSR is below or above the threshold (asymmetric). \(s_{it}\) is a threshold value, which determines the CSR level that changes its marginal impact on performance and it is identified uniquely for every i and t. Depending on the estimates of the parameters, the threshold value \( s_{it}\) might be constant across the sample (i.e., γ0) or might depend on Z (i.e., γ1). The sign, the magnitude and the significance of these coefficients provide a full description of the CSR–CFP link, as well as how and how much it is affected by the additional dimension. The exponential function allows for a smooth asymmetric effect, the degree of which depends on the magnitude of Z. This allows for infinite variations, one for every firm, of the shape of the relationship between CSR and CFP, and, as such, this specification is less susceptible to misspecification error. If \(a_{2}^{low}\), \(a_{2}^{high}\), and γ1 are statistically significant, our model would generate a differently shaped relationship between CSR and CFP across different levels of Z. Equation (4) is the novelty that our approach suggests and it describes how a dimension/variable \(Z\) can affect the inflection point on each firm, as well the degree of curvature, \(a_{2}^{low}\) and \(a_{2}^{high}\).

Furthermore, the latent character of Z [Eq. (3)] implicitly assumes that other factors, \(\varepsilon_{3t}\), not included in the vector \(CV_{Z,qit}\), can affect the shape of the relationship between CSR and CFP in a non-linear fashion [Eq. (4)]. This increases the generality of the threshold variable, \(Z\), while reducing the omitted variable misspecification error. The specification in Eq. (4) can be easily expanded to accommodate more threshold variables, fixed effects and/or a higher degree of asymmetry and thus account for a wider variety of firm-specific factors.

3.3 Model flexibility and potential extensions

One of the major contributions of our model over previous literature is that it is ‘investigative’ in nature, without imposing any predisposition with respect to the direction, shape or magnitude of the relationship between CSR and CFP. Previous models impose a structural form, motivated by an existing concept, e.g., the impact of a moderator/mediator, and test whether it is valid on a dataset or not. Our approach here is a lot more general and provides a way of accommodating various concepts. More precisely, we do not make any prior assumptions with respect to the direction/structure of the CSR–CFP relationship, but we let the data determine this relationship. We do that by using a system of equations, instead of a specific structural form and/or data manipulation that addresses endogeneity or sampling issues, which according to the sign and significance of the coefficients can identify the existence of (1) endogeneity, (2) direction, (3) mediators, (4) moderators and/or (5) a combination of them in a completely data driven way. Consequently, our model and its potential extensions that are discussed below could be used to test various theories or sampling properties without imposing a structural form or specific data treatment.

In more detail, different combinations of coefficient signs and significance would indicate the presence of various, previously reported, aspects of the CSR–CFP relationship. For example, in Eqs. (1) and (2), coefficients \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}}\) and \(\beta_{1}\) investigate whether there is any endogenous relationship between CSR and CFP. If only one of the two is significant, our model identifies that there is a one-directional effect, while if both are significant it identifies the presence of endogeneity. This is done in a natural way, without altering the structural form or the dataset and therefore if provides a general way of testing directional effects. This can also be extended to investigate endogeneity of higher order. Coefficient \(\beta_{2}\) captures the impact of Z on CSR, while Eq. (3) examines potential endogeneity among CSR, CFP, and Z as captured by coefficients \(\mu_{1}\) and \(\mu_{2}\). This approach is preferred over an instrumental variables specification (e.g., Cornett et al. 2016) because it introduces a level of generality that can conceptually nest/empirically test previous approaches. For example, one of the most important aspects of our model is that it can test for higher order interactions and their nature, e.g., moderators or mediators, in a natural data driven way. If only \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}}\) is found to be significant, while \(\alpha_{1}\) remains insignificant, this would indicate that the control variable used as a third dimension is a pure moderator, while if all \(\alpha_{1}\), \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}}\) and \(\mu_{2}\) are statistically significant, then CSR has both a direct and an indirect impact on CFP, with \(Z\) acting as a mediator. Furthermore, the composition of Eq. (3) could capture a ‘managerial recipe’ (Isaksson and Woodside 2016), especially if Z is defined as a completely latent variable.

Another major contribution of our model is the introduction of Eq. (4), which is flexible enough to capture various shapes of the link between CSR and CFP, without imposing a specific structural form like a quadratic function (e.g. Barnett and Salomon 2012) or structural breaks (e.g., Flammer and Bansal 2017). In more detail, Eq. (4) is flexible enough to allow a linear [e.g., monotonically increasing (decreasing) \(a_{2}^{low} = a_{2}^{high} > 0\) (\(a_{2}^{low} = a_{2}^{high} < 0\))] or a non-linear [e.g., exponential growth (decay) \(0 > a_{2}^{low} > a_{2}^{high}\) (\(a_{2}^{low} < a_{2}^{high} < 0\)) and logistic growth (decay) \(0 > a_{2}^{high} > a_{2}^{low}\) (\(a_{2}^{high} < a_{2}^{low} < 0\))] relationship. It can also accommodate a concave (e.g., \(a_{2}^{low} < 0\) and \(a_{2}^{high} > 0\)) shape and a convex (e.g., \(a_{2}^{low} > 0\) and \(a_{2}^{high} < 0\)) shape. The logistic function simply assumes exponential smoothing and does not affect the fundamental shape of the relationship.

However, the selection of an observable variable as a threshold variable might be limiting, in the sense that it might not be able to capture non-observable factors. To this extent, the inclusion of \(\varepsilon_{{3t{ }}}\) adds a latent character to the threshold variable \(Z\). This implies that factors not considered in Eq. (3) can also influence the shape of the relationship between CSR and CFP; therefore, it implicitly assumes that it is not only \(Z\) that affects this relationship but other relevant factors [e.g., known (\(CV_{Z,i,t}\)) and unknown (\(\varepsilon_{{3t{ }}}\)) factors] through their impact on \(Z\). Consequently, this specification allows a threshold variable to be used as an empirical proxy for the status of the firm.

If this is not sufficient, though, or if it is too restrictive, the model can be easily extended in various directions. If more firm-specific factors need to be considered, Eq. (4) can be extended by allowing more variables to affect the threshold values (e.g., \(s_{it} = \gamma_{0} + \sum\nolimits_{j = 1}^{J} {\gamma_{j} } TV_{jit}\)) where \(TV\) is a vector of threshold variables and/or fixed effects. Furthermore, if focus lies on the state of the relationship (e.g., high or low) rather than on the shape or the degree of the transition, a more stochastic approach could be selected. Instead of using a deterministic (e.g., size) or semi-latent (e.g., structural equation) variable, a completely unobservable (latent) variable with observable discrete states could be employed, where the transition from \(a_{2}^{low}\) to \(a_{2}^{high}\) follows a Markov switching framework. Finally, a greater number of regimes could be considered, should a higher degree of non-linearity be required.

3.4 Introducing a higher dimension

In this study, we claim that examining the CSR–CFP link in a binary context is inadequate to capture firm, market, or regional stylized factors; therefore, empirical studies so far generate conflicting results. Instead, we share the view that the CSR–CFP link might be affected by other mediators/moderators or latent factors. In the model presented above we propose and explicitly model an additional dimension of the CSR–CFP link, which requires the selection of an observable variable as an intermediating factor. For this purpose, we choose firm size \(\left( {Size_{it} = log\left( {Total Assets_{it} } \right)} \right)\), as one of the possible options, because it is well reported in the literature to be highly correlated with both CSR and CFP (e.g., Bowen 2002). This is not an identification statement and we also test the robustness of our findings with alternative firm specific factors, such as R&D expenses.Footnote 7

Unlike early literature (e.g., Mansfield 1962) and the ‘Law of Proportionate Effect’ (Gibrat 1931), several studies report a significant interaction between firm size and CFP. A branch of literature (e.g., Shepherd 1972) suggests that larger firms enjoy increased financial returns due to economies of scale (e.g., Stigler 1958), higher efficiency (Rappaport 1998), greater market share (Amato and Wilder 1985), and/or greater market power/concentration (Shepherd 1972), although they suggest that the exact relationship exhibits strong industry effects (e.g., Amato and Amato 2004). In contrast, several other studies (e.g., Evans 1987) report a negative correlation between firm size and profitability due to diseconomies of scale (e.g., Ratchford and Stoops 1998), diminishing returns to the fixed productivity factors (e.g., Marshall 1961), and/or organizational costs (e.g., Williamson 1967). In parallel, other studies argue that the link between firm size and CFP is highly empirical (Audretsch et al. 2002) and might depend on the balancing of administrative overheads and fixed costs, which decrease with size but increase with organizational complexity (Blau 1970).

Along the same lines, a significant part of the literature recognizes the impact of firm size on CSR. Early literature, driven by agency theory, links the intensity of CSR to greater managerial autonomy (Atkinson and Galaskiewicz 1988) and utility (Navarro 1988), which are more evident in larger firms. The stakeholder theory complements this view by focusing on the economic benefit of CSR. Firms that better meet their stakeholders’ needs are rewarded by higher legitimacy (Hooghiemstra 2000) and better access to resources. Inevitably, the literature at this stage recognizes that organizational (i.e., firm-specific) characteristics might affect the outcome of CSR actions (e.g., Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). The firm’s organizational architecture is industry dependent, but it is also highly correlated to firm size; therefore, it is seen as a major determinant of the effectiveness of CSR actions (Udayasankar 2008).

Firm size is linked to market power, visibility, and governance structures, which are hypothesized to have a strong impact on CSR strategy implementation (e.g. Etzion 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Although some studies (e.g., Meznar and Nigh 1995) consider larger firms more resistant to external influences and thus less socially responsive, most studies consider larger firm size to be associated with more intense CSR strategies. They consider larger firms to have better established governance (Schreck and Raithel 2018) and administrative practices (Donaldson 2001), and this would lead to a greater responsiveness to social issues (Brammer and Millington 2005). In addition, larger firms are more visible (e.g., Etzion 2007; Brammer and Millington 2008), and it should be easier for them to convey information to their stakeholders (Darnall et al. 2010). They tend to invest more in CSR, especially in the presence of an intrinsic value that increases their competitive advantage (Chih et al. 2010), or due to higher corporate reputation (e.g., Fombrun and Shanley 1990), or in order to reduce the asymmetry of information between managers and shareholders (Brammer and Millington 2005). In parallel, their investment strategy should be affected to a greater degree by shifts in stakeholders’ needs, as it is easier to associate them with “good” or “bad” practices, due to increased visibility (Watts and Zimmerman 1986), increased social pressure (Aguilera et al. 2007), or reduced size-related costs because of CSR disclosure (Ness and Mirza 1991).

Consequently, size is found to be a significant determinant of both CSR and CFP, with implications as for SMEs or non-listed firms (e.g., Spence 2016). We build on this idea and propose that, since size interacts with both, it might be endogenous (Orlitzky 2001; Surroca et al. 2010) with either/both and that it might affect the effectiveness of CSR actions and thus the way CSR and CFP interact. We try to merge all these concepts by considering firm size as an integral part of the CSR–CFP nexus. Again, we stress out that this is not an identification statement. Firm size is selected because it has been reported in the literature to have an impact on both CSR and CFP and potentially on both or on how they interact. Consequently, we consider it a suitable starting point to be investigated as a third dimension. Our framework could empirically identify how it interacts with CSR and CFP, in a data driven way, without imposing any functional form or conceptual restriction.

3.5 Confounding effects and control variables

Our model provides a general setup that the employed in order to investigate various aspects of the CSR–CFP relationship. However, this cannot be done without accounting for confounding effects. Our system of equations approach is very flexible and allows for a selection of different confounding factors for each one of the main components of the model, namely CSR, CFP and Z. Previous approaches that employ a single equation can only use a single set of variables that account for confounding effects, implicitly assuming that the same set of factors affect both directions of a potentially endogenous relationship. In our model, a different set of factors can be selected according to relevant theory and/or previous empirical findings.

Without it being an identification statement, the model in Eqs. (1)–(4) is estimated using the following control variables. We account for other firm-specific effects using a set of control variables, \(CV{=}\big( Growth,\;IntCov,\;Debt\;ratio,\;Current\;ratio,P/S,FA/TA,\;IA/TA \big)\), that stand for growth, interest coverage ratio, total debt ratio, current ratio, pricesales ratio, fixed assets over total assets, and intangible assets over total assets, respectively. Each equation has a unique set of control variables, captured by \(a_{q} ,\beta_{q} ,{ }\mu_{q}\).

The first control variable is growth (Growth), which is an integral part of CFP, as higher growth (Easton 2004) is a measure of increased profitability. Smaller firms usually experience higher growth (Gupta 1969), while the link between CSR and growth depends on available investment opportunities (Branco and Rodrigues 2006). Furthermore, firms will prioritize financial stakeholder claims over social stakeholders (Artiach et al. 2010). Therefore, highly leveraged firms should be less likely to improve their CSR profiles, even though it would further decrease their tax liability. However, CSR might contribute to sustainability of earnings and therefore reduce the overall risk (Husted 2005). We control for capital structure (debt ratio) in all three variables and allowed risk in the form of interest payments (IntCov) to be a determinant of CSR. We also control for liquidity (current ratio) and the perception of the market regarding the quality of sales (P/S). Finally, management might prioritize real investments (Chung et al. 1998) or intangible investments (Branco and Rodrigues 2006), depending on their marginal contribution to market value (Mackey et al. 2007). We use fixed assets (FA/TA) to control for the impact of real investments on CFP and SIZE, and Intangible Assets (IA/TA) as a determinant of CSR.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Initial observations

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the full sample and three sub-samples. Firms in advanced economies, namely the EU and the US, invest more in intangible assets, while real investments are more important for firms in the sample denoted as ‘Rest Of the World’ (i.e., ROW), which mainly consists of less developed economies. The total investment in fixed assets is larger in ROW (0.3007) than in the EU and the US (0.2597 and 0.2918), while the investment in intangible assets is more important in developed economies (EU: 0.6690, US: 0.6086, and ROW: 0.5784). This is consistent with CSR ranking across these regions. EU firms score higher on average (0.4305), followed by the US (0.3378) and ROW (0.2728).

Table 1 also provides insight on how investments in intangible assets are related to CFP and risk. Advanced economies exhibit higher ROE and ROA (ROE is 0.0615 in ROW, 0.1527 in the EU, and 0.1871 in the US), mainly due to a long left tail in ROW (skewness = − 3.60). The US and the EU exhibit higher P/B ratios (ROW: 1.7347, EU: 3.3685, and US: 3.7155), mainly due to a shorter right tail (skewness = 6.52 and kurtosis = 64.89 in ROW). The major difference between ROW and the other two might be related to a lower investment in intangible assets and might be due to higher risk in ROW. This is a first sign that CSR and CFP might be correlated, but no safe conclusions can be drawn on whether more profitable firms are more likely to invest in CSR or whether CSR investments contribute to profit stability and thus to reduced risk.

Focusing on this, the risk statistics confirm the differences between ROW and the other two groups. Moreover, ROW, the EU, and the US appear to be progressively less risky, and firms in ROW exhibit considerably lower total debt ratios (0.5868) than their counterparts in the other two groups (EU: 0.6761 and US: 0.6111), while also sustaining higher current ratios (ROW: 1.8169, EU: 1.7147, and US: 1.5748). This increased risk taking might be due to increased profitability and increased ability to cover interest payments (interest coverage ratio = 0.0796 in ROW, 0.3272 in the EU, and 0.4512 in the US) or might be due to lower market risk. Extending this idea, a considerable difference is observed between ROW and the other two groups; firms in advanced economies are more profitable, show greater investment in intangible assets, operate at higher risk levels, and exhibit higher firm values. Again, CSR and CFP seem to be linked, and this is an attribute shared by risk taking. However, it is yet not clear whether lower overall risk allows greater investments in intangible assets, which increases profitability, or whether higher profitability is a determinant of risk taking and investments in intangible assets or is potentially endogenous.

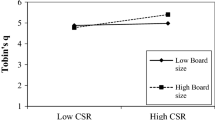

Firm size could probably provide deeper insight on the link between CSR and CFP, revealing size-related effects. Table 1 reveals that it is higher in the US (7.4318) than in EU (7.2175) and in ROW (7.2051), which is consistent with profitability and market value. Table 2 shows that size is highly correlated with investments in intangible assets (0.5261), CSR ranking (0.2829), borrowing levels (0.5047 with debt ratio), and profitability (− 0.0716 with ROE and − 0.2282 with ROA). This indicates that size might indirectly affect CSR and CFP or their link or that it might be endogenous. This is further investigated in Fig. 1 by measuring the average market value (P/B) and profitability (ROE) across firm size and CSR. We first investigate the impact of size on earnings (ROE, Panel A, Fig. 1) and on the market valuation of the firm’s net assets (P/B, Panel B, Fig. 1) which indirectly accounts for the market valuation of intangible assets and of CSR investments. CSR and ROE exhibit a U-shaped relationship, but this is not constant across size. For smaller firms, lower and higher CSR is linked with higher ROE, while mediocre CSR exhibits the lowest. In contrast, larger firms exhibit higher ROE with improved CSR. In between, higher and lower CSR is consistently associated with higher ROE, but the cut-off point where better CSR ranking is translated into higher ROE decreases as size increases.

ROE, P/B, Size and CSR (Vigeo). This figure presents the average ROE (Panel A) across different levels of Size and CSR for the full sample (Vigeo), as well as for the three sub-samples employed: Rest Of the World (ROW), Europe (EU) and the United States (US). Panel B presents the average P/B ratio across different levels of Size and CSR for the full sample, as well as for the three sub-samples employed: Rest Of the World (ROW), Europe (EU) and the United States (US)

These differences become more apparent upon examination of the sub-samples. In ROW, ROE decreases with higher CSR in relatively smaller firms, while a higher CSR ranking has a clearly positive impact on ROE in relatively larger firms. In the EU, the worst-performing firms seem to be those of medium size and medium or low CSR. In the US, the asymmetric effect of CSR on returns is more evident in smaller firms but larger firms seem to also benefit, almost monotonically, from a higher CSR. Two major conclusions can be drawn from this analysis. First, the link between CSR and CFP appears to indeed be asymmetric and non-monotonic but not for all firm sizes. It appears to follow a U-shaped pattern for smaller-sized firms while exhibiting a non-monotonically increasing pattern as size increases. Consequently, we suggest that the U-shaped link reported in previous studies is non-monotonic across size and is observed in the tails of the size distribution. Second, there is an overall U-shaped pattern that exhibits a decreasing significance across size, indicating that there is a notable size effect in the way CSR and CFP interact. The tipping point of the U-shaped link decreases with larger size up to a point where CFP increases monotonically with CSR in firms of relatively higher size. Therefore, the U-shaped link is mainly observed in small firms, while the effect of decreasing returns due to mediocre CSR performance (Barnett 2007; Barnett and Salomon 2012) becomes less significant in larger firms. These two points become more apparent when we focus on market values (i.e., P/B).

4.2 Parametric analysis

The previous section highlights several implications derived from non-parametric analysis, which could be summarized in the following principal concerns. The CSR–CFP relationship appears to be asymmetric and potentially endogenous. We observe that the importance of this notable asymmetric relationship between CSR and CFP decreases across a third dimension, namely, firm size, to a monotonically increasing function, exhibiting strong regional variations. The tipping point, where the marginal impact of CSR on CFP turns positive, appears to change across different size levels. However, such a non-conditional analysis cannot identify this tipping point, while it cannot account for endogeneity either. We further pursue this task in this section, aiming at measuring the direct and indirect impact of size on the CSR–CFP link.

4.2.1 Size and asymmetry

One of the major attributes of our model is that it explicitly models a potentially asymmetric impact of CSR on CFP (ROE) and allows for an additional factor (Size) to have a direct impact on ROE and on how ROE is affected by CSR. The first column of the second panel of Table 3 presents the estimation results for Eq. (1).

ROE appears to be asymmetrically affected by CSR. Low (high) CSR has a diminishing (− 0.0363) [increasing (0.0181)] impact on ROE. This is consistent with previous literature (Barnett 2007) that reports a U-shaped relationship and we expand on this by measuring the exact inflection point for every firm, as well as by investigating how it changes across a third dimension. An estimate of 0.4131 for \(\gamma_{0}\) indicates that this is an a-priori threshold level of CSR performance (assuming 0 Size). Any level below this has a diminishing impact on CFP and it is the inflection point where the marginal impact of CSR turns positive. This threshold value, however, does not remain stable across different levels of Size. The estimate of γ1 is negative (− 0.0420) and shows that the inflection point is lower for larger firms. This is consistent with previous studies (Brammer and Millington 2008) arguing that larger firms can more easily capitalize on their CSR investments. Table 3 also shows that these empirical findings are robust to alternative estimation methods.

Figure 2 graphically depicts these findings and presents the parametric estimate of ROE according to Eq. (1) for different levels of Size. ROE decreases in low CSR levels and only starts increasing after a threshold is exceeded. According to the estimates of Eq. (4), Size has a diminishing impact on the threshold value, which is lower for larger firms. This can be observed by a shift to the left of the minimum point.

Return on Equity across different levels of CSR (Parametric) and firm Size (Vigeo, KLD and ESG). This figure presents the parametric estimate of ROE across different levels of CSR according to the estimates of the Eqs. (1)–(4), presented in Tables 3 and 5, for the Vigeo (Panel A), the KLD pre-2010 (Panel B) and ESG post-2010 (Panel C) datasets. ROE has been computed focusing on the marginal impact of CSR on ROE assuming an average \(\alpha_{0}\) equal to the unconditional average ROE and \(a_{0,p} = a_{q} = 0 \;\,\forall p,q\). Firm size is dissected into small (\(Size = 3\)), medium–low (\(Size = 5\)), medium–high (\(Size = 7\)) and large (\(Size = 9\))

4.2.2 Size and endogeneity

Would always be profitable to intensify the CSR strategy? According to the findings above, this would depend on the unique identification of the tipping point, how it interacts with the additional dimension considered and inevitably the existence of potential endogeneity. The second and third columns of the second panel of Table 3 report the estimates of the parameters of Eqs. (2)–(3) for the full sample.

CSR and CFP seem to be endogenously related. An estimate of 0.0127 for ROE indicates that firms with higher profitability are more likely to invest in CSR and thus achieve higher CSR performance. Higher CSR can also boost ROE but only in larger firms. In fact, higher CSR investments in smaller firms are associated with lower profitability. In addition, Size appears to be endogenous to both CSR and CFP. An estimate of − 0.0449 associates larger firms with lower earnings (ROE). This correlation is strong, and higher-earning firms indeed appear to be smaller (ROE on Size is − 0.0636). At the same time, an estimate of 0.1014 shows that larger firms are more likely to invest in CSR and are associated with higher CSR performance. This in turn can lead to larger size (CSR on Size is 0.6241), indicating that CSR and size are endogenous.

Collectively, this reveals a spiral and endogenous relationship. Larger and more profitable firms are more likely to invest in CSR, which is expected to further increase Size, which in turn determines whether increased CSR investments will enhance CFP. Looking at it from a corporate finance point of view, CSR investments might be a preferred strategy with respect to CFP for firms that expect a negative impact of Size on CFP due to their larger SIZE. Increasing Size would not be a sensible option since this would decrease CFP. However, increased investments in CSR would enhance Size and then indirectly enhance CFP or at least would mitigate the negative direct impact of Size on CFP. In contrast, small firms should aim at increasing Size because this would reduce the threshold value, which in turn would increase the marginal contribution of CSR on CFP.

4.3 Robustness: regional, firm-specific factors and generalizability

The major contribution of our model is that it allows, the data to uniquely identify the inflection point for every firm. The firm-specific focus is by construction free from cross-sectional differences and has the potential to capture several inconsistencies, previously reported in the literature. However, the estimates refer to a full sample estimation and cannot indicate whether the model is sensitive enough to capture regional, market, or firm-specific differences and whether the identification of the threshold variable contributes to a better description of the relationship between CSR and CFP.

Would the results be consistent if the model were applied in different samples or if the additional dimension consisted of more or different control variables, other than firm size? In this section, we estimate the model in different samples/datasets to test whether the model is sensitive enough to provide estimates of the parameters that capture regional/market/data-stylized effects. In addition, we appreciate that the choice of one specific control variable or this specification of non-linearity might be restrictive. We re-estimate the model with a different specification of Eq. (4) that considers a linear/constant specification as well as that the third dimension might include more or different variables, such as Research and Development (R&D) expenses.

4.3.1 Measuring financial performance (CFP)

We test the robustness of our findings by considering another accounting (internal) measure of managerial performance, the Return on Assets (ROA), and an indirect measure that accounts for external (market) valuation of the firm’s assets and consequently of the value of its equity capital (P/B), which yield comparable results.

ROA is expected to be highly correlated with ROE; yet, it might be driven by different fundamentals (or by the same fundamentals in a different way), such as the proportion of debt, taxation, and depreciation (investments in fixed assets, FA/TA, or intangible assets, IA/TA). The estimation results are presented in the first panel (columns 4–6) in Table 4. Firms with higher ROA are found to be more likely to invest more in CSR (the estimate of ROA on CSR is 0.0440), which in turn might result in a larger size (the estimate of CSR on Size is 0.6403). The direct impact of Size on ROA is rather diminishing (− 0.0180), but it can be mitigated by higher (above the threshold of \(0.3890 - 0.0324 \times Size\)) CSR performance, which is found to increase ROA (the estimate of high CSR on ROA is 0.0244). In contrast, when CSR performance is below the threshold, ROA is even lower (the estimate of the low CSR on ROA is − 0.0319). The threshold value seems to be inversely (− 0.0324) linked to Size.

In addition, most studies use ROE to measure CFP, as opposed to a market-based performance measure, such as Tobin’s Q and the P/B ratio. The reason for this is the marginal contribution of CSR investments on profits rather than on the cost of goodwill in terms of improved social image/brand name. In addition, it also better matches the backward-looking character of our proxy for CSR, namely CSP. However, we recognize that if there is a “true” CSR–CFP relationship, especially on a firm level, it should also be reflected on market values, as well as on other CFP measures too. Therefore, we test the robustness of our findings to a market-based (Price to Book ratio (P/B)) measure that focuses on valuation. The findings (first three columns of Table 4) are magnified. The long-term, cross-sectional mean of P/B is 4.0702 for the full sample and is consistent with the non-parametric estimate in Table 1. In accordance with previous findings, low CSR has a diminishing (− 0.0460) impact on P/B, whereas high CSR significantly boosts (0.0279) market values. The threshold value is still comparable at 0.4108, falling by 0.0421 for every unit increase in Size. These findings suggest that both the asymmetric relationship and the diminishing effect of size are greater in magnitude when market values are considered, which highlights the importance of CSR for investors. Furthermore, firms with high P/B ratio are more likely to invest in CSR (P/B on CSR is 0.0241). This investment will lead to larger size (CSR on Size is 0.6208), which, like in previous (ROE) findings, will have a dual impact on market value; a negative direct (Size on P/B is − 0.1012) and a positive indirect (lower CSR threshold) impact.

4.3.2 Regional factors

We test the adequacy of the model in capturing potentially differential degrees of endogeneity and asymmetry by re-estimating the model in different market environments (ROW, EU, US), which implicitly account for regional differences and market-stylized factors. The second panel (columns 7–15) of Table 4 presents the estimation results, which confirm our previous findings. For example, ROE in the EU is found to increase CSR performance (0.0123), which in turn leads to greater size (1.0303) and higher financial performance (0.0166), when CSR is greater than the threshold value (\(0.4177 - 0.0422 \times Size\)), and vice versa (low CSR is − 0.0362).

However, the major difference lies in the different measurements of the degree of convexity between CSR and CFP in each market. The maximum threshold value is consistently lower in advanced economies (ROW: 0.4680, EU: 0.4177, US: 0.4150). Size is also found to significantly improve the profitability of CSR investments by lowering the threshold value (γ1 is ROW: − 0.0417, EU: − 0.0422, US: − 0.0425) and is associated with higher asymmetries (greater absolute difference) in advanced economies [CSR-low vs. CSR-high on ROE is ROW: − 0.0103 (− 2.66) vs. 0.0120 (2.65), EU: − 0.0362 (− 4.18) vs. 0.0166 (3.83), US: − 0.0649 (− 4.88) vs. 0.0233 (5.55)]. These observations highlight the flexibility of our model in capturing varying degrees of non-linearity and endogeneity.

4.3.3 Inter-temporal differences, market-stylized factors and data samples

We test the robustness of our findings to alternative CSR scores, as well as their evolution in time and in different market environments. Previous studies report the inability of the existing CSR measures to capture the breadth of CSR (Carroll et al. 2016), as well as their failure to converge (Chatterji et al. 2016). If our model captures the “real” CSR–CFP link, its conditional propositions should be “on average” consistent independently of the CSR measure used and it should be flexible enough to capture changes in the intensity of the interaction. We address this issue in two ways. First, we employ different composite CSR scores, provided by different data vendors, which apply different criteria, as well as different weighting factors. Second, we decompose these scores into their constituent parts in order to investigate the ability of our model to capture more specific elements of the CSR–CFP relationship.

For the first part, we extend our analysis with another two samples consisting of firms listed in two S&P indices with valid observations for financial data and KLD and ESG (Bloomberg) scores for two periods; 1997–2010 (pre-2010) and 2011–2017 (post-2010). This approach tests the robustness of our findings to alternative market environments (e.g., the S&P indices), as well as potential evolution of the shape of the CSR–CFP relationship (e.g., between 1997–2010 and 2011–2017). Our model should be flexible enough to capture both.

The second panel of Table 5 presents the estimation results for the full model using the KLD, as well as the ESG rating, which confirm qualitatively the robustness of our results. We confirm the asymmetric impact of CSR on CFP, with the threshold value being a diminishing function of Size. The impact of a low CSR rating on CFP is again negative (CSR-low is − 0.0272 with KLD and − 0.0516 with ESG), while it increases (CSR-high is 0.0323 in KLD and 0.0385 in ESG) when CSR exceeds a threshold that is reversely related to Size (γ0 is 3.1504 and γ1 is − 0.6195 in KLD and 0.5050 and γ1 is − 0.0350 in ESG). The impact of Size on the tipping point is plotted on Panels B and C of Fig. 2. Due to the range of the KLD measure the effect of the third dimension—shifting the threshold to the left—is even more pronounced, while it is highly similar (to Vigeo) when the ESG score is employed. However, the qualitative interpretation remains identical. This is a strong evidence that the relationship we report, using our model, is robust to measurement bias and temporal variation.

For the second part, we decompose each composite score into its constituent parts, as they are provided by the CSR rating agencies. Then, we replace in the estimations the composite score with each one of the sub-scores and report the results in Table 6, where the Vigeo score is decomposed into six domains: human resources (HR), environment (ENV), business behavior (C&S), corporate governance (CG), community involvement (CIN), and human rights (HRT). The KLD score is decomposed into strengths and concerns; each one computed as the sum of strengths or concerns, respectively. The ESG score is decomposed into three domains; Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance. The first panel (top half) of Table 6 presents the estimation results for the constituents of the Vigeo score, while the second panel (bottom half) presents the estimation results for the KLD and ESG scores.

The first notable observation is that our model appears to be flexible enough to capture differences on how each sub-score interacts, if at all, with CFP. This is observed when focusing on the estimates of the CSR-low vs CSR-high parameters in each one of the scores. Their magnitude and sign changes when a different CSR domain is employed. This shows that the model is flexible enough to capture both the shape and the intensity of the CSR–CFP link. For example, strengths (concerns) appear to monotonically increase (decrease) CFP. In addition, in accordance with Nollet et al. (2016), we find that the non-linearity is not persistent across sub-scores. In fact, we confirm that it is present when the corporate governance score is employed, but we report the same for the human resources score. In contrast, all other scores exhibit a monotonic relationship, which is persistent across different levels of magnitude of each score. This cannot be captured by pre-determined structural form, like the quadratic function used in previous studies (e.g., Barnett and Solomon 2012; Nollet et al. 2016) and it is a major merit of our modelling. Furthermore, a closer investigation of these differences reveals an additional feature that might be present in the CSR–CFP relationship. The two domains that exhibit a non-monotonic relationship, namely corporate governance and human resources, are internal to and can be controlled by the firm, while the other dimensions, e.g., the environmental and social interactions, that exhibit a monotonic link, lead to externalities. This provides some evidence that CSR actions that have externalities either increase or decrease CFP, according to the sign of the externality. In contrast, actions that are focused on the firm do not unconditionally lead to higher CFP. This might be somewhat intuitive, suggesting that actions that are easier (more difficult) to control, such as internal actions (external actions with externalities) might be more difficult (easier) to yield results, since their visibility/exposure is greater. This is a primary finding derived by using our model and we believe that it merits further investigation.

4.3.4 Functional form

Finally, we test the robustness of our analysis with respect to how the additional dimension of the CSR–CFP nexus is modeled, in terms of functional form and control variables. We do this by considering a linear version of our model as well as extending Eq. (4) in two directions. First, we allow an additional, relevant variable, namely R&D expenses, to have an impact on the identification of the tipping point, as well as a direct impact on the endogenous variables. Second, we model this variable, assuming trifold endogeneity.

The estimation results of the linear specification are presented in the first 6 columns of Table 3, where \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}} \equiv a_{2}\) and Eq. (4) is redundant. The estimation results remain qualitatively the same but the impact of CSR on CFP is found to be weaker (0.0079) and less significant (2.32), resulting in a worse fitting (Adj-R2 and MSE are 20.58% and 0.1846 in the linear version and 40.12% and 0.1199 in the non-linear version). This is probably due to the fact that one parameter identifies a non-linear relationship (\(a_{2}\) summarizes \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}}\)). Depending on the signs, the magnitude and the significance of the coefficients in \(a_{2}^{^{\prime}}\), \(a_{2}\) might be positive, negative and/or insignificant, but most importantly sample dependent. Therefore, we suggest that the identification of the threshold level and consequently, the explicit design of the non-linearity might be the reason why previous (linear) studies might generate conflicting results. Our model captures sample dependent differences without sub-sample estimations and therefore it can capture a more fundamental link between CSR and CFP.

Naturally, the fitting of the model and its ability to adequately describe the CSR–CFP relationship depends on how the additional dimension is modeled. Towards this direction, we suggest an enhanced specification of Eq. (4) that accounts for another relevant control variable; R&D expenses. Recent literature investigates the marginal impact of R&D activity on CFP and CSR and considers R&D expenditures as investments in intangible assets (Chan et al. 2001; Eberhart et al. 2004; Ehie and Olibe 2010), which contribute to differentiation and the development of competitive advantages and thus to longer term growth and profitability. We address this by including \(IA/TA\) as a control variable. However, more recent studies report that, when R&D investments are explicitly considered, the marginal impact of CSR on CFP becomes insignificant (McWilliams and Siegel 2000) or is only significant in low innovation firms (Hull and Rothenberg 2008), while R&D investments are positively correlated with CSR (Luo and Du 2015), exhibiting strong industry effects (Padgett and Galan 2010).

We test the above propositions by estimating an enhanced version of our model. There are two estimations. In the first, we add R&D as an explanatory variable in Eqs. (1) and (2), as well as a determinant of \(s_{it}\) in Eq. (4). This extends our model by including more threshold variables and investigates how the CSR–CFP link changes across two dimensions. The second extension uses another dimension instead of Size, namely R&D investments, and aims at investigating whether the non-linear link still exists.

The empirical findings presented in the top panel of Table 7 suggest that, under the presence of R&D, which marginally increase CSR [0.0525 (2.34) in Vigeo, 0.5853 (4.66) in KLD and 0.2234 (3.01) in ESG], the impact of size is strengthened [0.1034 (7.92) in Vigeo, 0.1899 (6.70) in KLD and 0.1446 (3.56) in ESG]. This suggests that larger firms invest more in CSR, either due to available resources (Chih et al. 2010) or because they have a lack of differentiation/innovation (Hull and Rothenberg 2008). With regards to the profitability of the CSR investments, they become profitable when CSR performance exceeds a threshold [0.0199 (4.96) in Vigeo, 0.0413 (2.92) in KLD and 0.0302 (3.77) in ESG]. This threshold is negatively affected by Size [γ1 is − 0.0420 (− 5.16) in Vigeo, − 0.8943 (− 5.50) in KLD and − 0.0310 (− 6.59) in ESG] and now positively affected by the level of R&D investments [γ2 is 0.0869 (2.90) in Vigeo, 0.4058 (4.34) in KLD and 0.0314 (3.94) in ESG]. This means that larger firms still benefit more by CSR, but this effect is weaker. The threshold value is elevated upon the presence of significant R&D investments, which implies that firms with significant differentiation/innovation have alternative investment opportunities. These findings are also consistent when firm Size is replaced by R&D expenses (the bottom panel of Table 7) and highlight the flexibility of the model to capture various stylized factors.

5 Conclusions and discussion

“Does it pay to be good?” This question refers to the marginal impact of CSR on CFP. Recent literature recognizes that CSR does not always contribute to higher CFP and therefore their link is asymmetric, usually U-shaped. Some studies attribute these asymmetries to endogeneity, while other studies consider that they are manifested by one or more interacting factors that can act as moderators/mediators. Although insightful, these studies operate under two restrictive conventions: (1) they consider a “universal” link between CSR and CFP that can be unconditionally applied to all firms, (2) there is a trade-off between describing either the shape of the relationship or the interacting factors.

We address both issues by focusing on a more granular level: each firm. We introduce an additional dimension, which we proxy using an endogenous semi-latent specification, and we explicitly model how it affects the shape of the CSR–CFP relationship. This way we attain two contributions: (1) we suggest a flexible modelling that describes simultaneously the shape of the CSR–CFP link and the interacting factor, without imposing a functional form or making assumptions about what drives it. All inference is data driven. (2) with our model we can identify explicitly, for the first time at a firm-specific level, the inflection point where the marginal impact of CSR on CFP turns positive. Consequently, any identified link would refer to a firm, accounting for firm specific factors, rather than an average cross-sectional depiction.

Our empirical findings confirm the asymmetric link between CSR and CFP but at a more granular level than previously thought. Indeed, there is a U-shape link between CSR and CFP, but its curvature is unique per firm. Therefore, the previously reported universally applied U-shape seems to be an “average” intensity curvature, which is the result of an aggregation of differently shaped individual relationships. This finding, which is robust to cross-sectional/measurement/specification differences, suggests that what previous studies identify “on average” is manifested because it holds at a firm level and when aggregated generates the previously observed U-shape. This firm level estimate is free from cross-sectional effects and therefore, it can explain previous conflicting results that arise due to these differences.

Finally, this, per firm, identification of the inflection point, which can also be conditional on any factors/key indicators of interest, has managerial implications too. Managers can identify key indicators that they believe will affect the profitability of their CSR investments. These indicators can be formulated into an additional dimension [i.e., an extended specification of Eq. (4)] and with this, they can identify the minimum threshold of CSR performance that they need to exceed in order for the marginal impact of CSR on CFP to be positive. With this, they can develop a profit maximizing strategy, relevant to the additional dimension. For example, according to our findings, smaller/higher R&D intensity firms might be better off if they first manage their Size/R&D intensity in order to reduce the CSR threshold, instead of simply intensify CSR investments.

Notes

CSR is the discretionary societal expectations of a firm (Carroll 1979). This explicitly differentiates social from financial objectives, implicitly recognizing that not all CSR actions are profitable. However, because this is a forward-looking (latent) concept, we use an empirical proxy, Corporate Social Performance (CSP) (Carroll et al. 2016), which measures how socially responsible the firm has been in the past. This backward-looking proxy does not introduce estimation bias because we employ a backward-looking measure of CFP.

KLD methodology changed due to the transition to the MSCI ESG indices family that occurred on the 1st of September 2010; therefore, we collect KLD data until 2010 and the ESG (Bloomberg) data beyond 2010 to maintain consistency. Further information about the exact methodologies and social performance valuation can be found in RiskMetrics Group (2010) for KLD and in Bloomberg (2020) for ESG.

The data collection focuses on the period before the formalization of the Vigeo Euronext Indices and the Merge with EIRIS. Further information can be found in Vigeo Eiris (2020).

Carroll et al. (2016) argue that CSP scores might not reflect the true CSP of the firms, due to biases, such as regional factors (Shahzad and Sharfman 2017), the weighting used (e.g., García-Melón et al. 2016; Capelle-Blancard and Petit 2017) or simply because they do not adequately cover the breadth of CSR (e.g., Lamata et al. 2018; Oll et al. 2018). Even worse, Chatterji et al. (2016) report that the existing CSP scores do not converge and therefore, they might not be a good proxy for CSR. We address these concerns by testing the robustness of our findings to CSP-scores with different criteria, weighting and regional/cross-sectional coverage (Vigeo, KLD and ESG), which should be able to capture the diversity of these concerns.

The coverage of the KLD index was not extensive in the early stages and therefore, this sample mainly consists of the constituents of the S&P500 index. The estimation results are consistent when focusing only on S&P500.

The model can be estimated with various estimation methods appropriate for a system of equations. We use an iterative GMM procedure with Newey–West heteroskedasticity–consistent errors, as our main estimation method, but we also test the robustness of our findings with simpler estimation methods and we find them to be consistent. The use of instrumental variables can account for various econometric issues, identify more precisely the CSR–CFP link, while it is also consistent with the literature. For more information, please refer to the Online Appendix.

The selection of firm size as a third dimension is by no means an identification statement. We recognize that a single variable might not be enough to capture the complexity of the CSR–CFP. Therefore, we suggest a semi-latent modeling to account for other factors too, as well as various model extensions in order to incorporate other factors of interest or other functional forms. Consequently, by selecting firm size, we do not claim that it is the only or the best factor affecting the CSR–CFP link. Instead, we select a variable that is recognized in the literature to affect both, aiming at highlighting how an additional dimension can help explaining their relationship.

References

Agle, B. R., Donaldson, T., Freeman, E. R., Jensen, M. C., Mitchell, R. K., & Wood, D. J. (2008). Dialogue: Toward superior stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18, 153–190.

Aguilera, R., Rupp, D., Williams, C., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the s back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Amato, L., & Wilder, R. P. (1985). The effects of firm size on profit rates in U.S. manufacturing. Southern Economic Journal, 52, 181–190.

Amato, L. H., & Amato, C. H. (2004). Firm size, strategic advantage, and profit rates in U.S. retailing. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 11(3), 181–193.

Artiach, T., Lee, D., Nelson, D., & Walker, J. (2010). The determinants of corporate sustainability performance. Accounting and Finance, 50, 31–51.

Atkinson, L., & Galaskiewicz, J. (1988). Stock ownership and company contributions to charity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 82–100.

Audretsch, D. B., Klomp, L., Santarelli, E., & Thurik, A. R. (2002). Gibrat’s law: Are the services different? Review of Industrial Organization, 24(3), 301–324.

Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28, 446–463.

Avi-Yonah, R. (2005). The cyclical transformations of the corporate form: A historical perspective on corporate social responsibility. Delaware Journal of Corporate Law, 30(3), 767–818.

Barnett, M. (2007). Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32, 794–816.

Barnett, M., & Salomon, M. R. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33, 1304–1320.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Bass, A. E., & Milosevic, I. (2018). The ethnographic method in CSR research: The role and importance of methodological fit. Business and Society, 57, 174–215.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2010). Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica, 77, 1–19.

Blau, P. (1970). Formal theory of differentiation in organizations. American Sociological Review, 35(2), 201–218.

Bloomberg. (2020). https://www.bloomberg.com/impact/products/esg-data/. Accessed 14 January 2020

Bowen, F. E. (2002). Does size matter? Organizational slack and visibility as alternative explanations for environmental responsiveness. Business and Society, 41, 118–124.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2005). Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 29–44.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2008). Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29, 1325–1343.

Branco, M., & Rodrigues, L. (2006). Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 111–132.

Capelle-Blancard, G., & Petit, A. (2017). The weighting of CSR dimensions: One size does not fit all. Business and Society, 56, 919–943.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academic Management Review, 4, 497–505.

Carroll, R. J., Primo, D. M., & Richter, B. K. (2016). Using item response theory to improve measurement in strategic management research: An application to corporate social responsibility. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 66–85.

Chan, K., Lakonishok, J., & Sougiannis, T. (2001). The stock market valuation of research and development expenditure. Journal of Finance, 56, 2431–2456.

Chan, K. S., & Tong, H. (1986). On estimating thresholds in autoregressive models. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 7, 178–190.

Chatterji, A. K., Durand, R., Levine, D. I., & Touboul, S. (2016). Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 1597–1614.

Chatterji, A. K., Levine, D. I., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18, 125–169.

Chih, H. L., Chih, H. H., & Chen, T. Y. (2010). On the determinants of corporate social responsibility: International evidence on the financial industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 93, 115–135.

Chung, K. E., Wright, P., & Charoenwong, C. (1998). Investment opportunities and market reaction to capital expenditure decisions. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22, 41–60.

Cornett, M. M., Erhemjamts, O., & Tehranian, H. (2016). Greed or good deeds: An examination of the relation between corporate social responsibility and the financial performance of U.S. commercial banks around the financial crisis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 70, 137–159.

Crane, A., Henriques, I., & Husted, B. W. (2018). Quants and poets: Advancing methods and methodologies in business and society research. Business and Society, 57, 3–25.

Darnall, N., Henriques, I., & Sadorsky, P. (2010). Adopting proactive environmental strategy: The influence of stakeholders and firm size. Journal of Management Studies, 47, 1072–1094.

Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Easton, P. (2004). PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review, 79, 73–95.

Eberhart, A., Maxwell, W., & Siddique, A. (2004). An examination of long-term abnormal stock returns and operating performance following R&D increases. The Journal of Finance, 59, 623–650.

Ehie, I. C., & Olibe, K. (2010). The effect of R&D investment on firm value: An examination of US manufacturing and service industries. International Journal of Production Economics, 128, 127–135.

Etzion, D. (2007). Research on organizations and the natural environment, 1992-present: A review. Journal of Management, 33(4), 637–664.

Evans, D. S. (1987). The relationship between firm growth, size and age: Estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35, 567–582.

Flammer, C. (2015). Does corporate social responsibility lead to superior financial performance? A regression discontinuity approach. Management Science, 61, 2549–2568.

Flammer, C., & Bansal, P. (2017). Does a long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strategic Management Journal, 38, 1827–1847.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 233–258.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management. A stakeholder approach. Marshfield, MA: Pitman.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times Magazine, September 13.

Galbreath, J., & Shum, P. (2012). Do customer satisfaction and reputation mediate the CSR-CFP link? Evidence from Australia. Australian Journal of Management, 37, 211–229.

Garcia-Castro, R., Ariño, M. A., & Canela, M. A. (2010). Does social performance really lead to financial performance? Accounting for endogeneity. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 107–126.

García-Melón, M., Pérez-Gladish, B., & Gómez-Navarro, T. (2016). Assessing mutual funds’ corporate social responsibility: A multistakeholder-AHP based methodology. Annals of Operations Research, 244(2), 475–503.

Gibrat, R. (1931). Les Inégalités Economiques. Paris: Sirey.

Gully, M. S., Phillips, J. M., Castellano, W. G., Han, K., & Kim, A. (2013). A mediated moderation model of recruiting socially and environmentally responsible job applicants. Personnel Psychology, 66, 935–973.

Gupta, M. C. (1969). The effect of size, growth, and industry on the financial structure of manufacturing companies. The Journal of Finance, 24, 517–529.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–139.