Abstract

There are an increasing number of individual or corporate investors who demand social responsibility (SR) to a financial asset. Social responsibility is a multi-dimensional concept that requires identifying a number of criteria and their weights to be assessed in a financial asset. Currently a varied discussion is held among practitioners and academics with respect to this question. The common practice is to equally weight all the SR criteria. However, investors may wish to prioritize a particular dimension depending on their preferences. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to tackle this issue, e.g. to provide different weights for the different SR criteria according to the opinion of different stakeholders. These weights are later used in order to build a composite measure of SR and to rank mutual funds. To that end, Vigeo’s list of SR criteria is taken as the starting point for discussion. The Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) database gives the information for the companies’ SR performance according to those criteria. Stakeholders are selected according to various proposals and the Analytic Hierarchy Process is applied to weighting the Vigeo’s criteria according to the stakeholders’ preferences. The methodology allows not only assessing the financial assets but also tracking their evolution with the periodic Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) database updates. To prove the feasibility and utility of the methodology, a case study analysing Spanish equity mutual funds has been carried out. Among other results, the method shows that the so-called “responsible” funds do not perform particularly well in the SR assessment. Besides, we have found that there are few mutual funds with a good balance between financial and SR behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Current economic context: crisis and financial markets

The world economy has been affected by a financial crisis which has had severe, if variable, implications for Western economies with falls in investment, demand, output and employment (Herzig and Moon 2013), and the financial assets market has not been immune to these negative impacts.

Despite this very difficult economic context, or perhaps because of it, the Socially responsible investing (SRI) market is gaining popularity. Socially responsible investing can be broadly defined as an investment process that integrates not only financial but also environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into investment decision making.

The investment strategies used by socially responsible investors are mainly screening, community investment and shareholder activism. Screening, positive and/or negative, is the practice of evaluating mutual funds based on social, environmental, ethical and/or good corporate governance criteria. Nowadays is the most popular SRI strategy in most of the countries. Positive screening implies investing in profitable companies that make positive contributions to society, for example, that have good employer-employee relations, strong environmental practices, products that are safe and useful, and operations that respect human rights around the world. Conversely, negative screening implies avoiding investing in companies whose products and business practices are harmful to individuals, communities, or the environment.

Currently, one of the main instruments of SRI is investment in socially responsible mutual funds. The term ‘fund’ is used to refer to a ready-made financial product where investors’ money is pooled into a portfolio and a fund manager decides which shares to buy. A socially responsible fund is a fund where the selection of investments is based not only on financial but also on social, environmental, governance or other ethical criteria. The investors attracted by this kind of products are mainly passive investors. These are investors with medium-low financial knowledge willing to invest in already made financial products without making more decisions than those concerning to risk assumption. In this context, the discussion on the social and financial performance of socially responsible mutual funds is a key question (Renneboog et al. 2008, Cortez et al. 2009, Hellsten and Mallin 2006, Renneboog et al. 2011).

1.2 The European SRI market

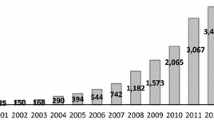

The 5th Sustainable and Responsible Investment Study by the European Forum for Sustainable Investment (Eurosif 2012), details the continued growth in assets under management (AuM) of the European SRI market and also reveals opportunities for future growth.

The assets managed by the European market for socially responsible funds in the year 2012 has reached 95 billion euro consolidating the growth (+12 %) of the recent years. This result is a confirmation of the strength of this segment of the asset management business that has maintained positive net inflows even during periods of markets volatility.

The study also highlights the growing diversity and sophistication of sustainable investment strategies in practice today. As an example, the norms-based screening strategy, the widest used SRI strategy in Europe, has seen a surge of 137 % in AuM since 2009 (Eurosif 2012).

According to Fig. 1, in Spain the SRI market remains considerably less developed than many of its Northern European neighbours. It remains a niche investment strategy dominated by a few large institutional investors, in particular large occupational pension funds. In this paper we will focus on the Spanish market as its foreseen expansion makes it a very attractive case study to be analysed (Spainsif 2012).

1.3 The Spanish SRI market: strengths and weaknesses

According to the Spanish Socially Responsible Investment Forum: SpainSIF (Spainsif 2012) despite the fact that the legal framework for SRI in Spain remains less robust than in many of its European neighbours, several recent developments point to promising perspectives in the near term horizon. For instance, the approved Sustainable Economy Law (Law 2/2011, March 4, 2011) calls for pension funds to disclose on an annual basis whether or not they use social, environmental or governance criteria in their investment approach. In addition, a recently passed law modernizing Spain’s Social Security system calls on employer-sponsored occupational pension plans to disclose whether they incorporate the analysis of ESG risks as part of their investment selection process.

Therefore, the role of practitioners and academics is becoming very important for the evaluation of the social responsibility degree of financial assets. This assessment is not new and Steuer et al. (2007) and Zopounidis and Doumpos (2013) acknowledge the inclusion of non-financial criteria in recently published financial multicriteria decision making models. Practitioners and researchers have acknowledged the growing concern of investors, individual and institutional, about ethical, environmental, social and governance issues, even if just taken as a way of decreasing the investment risks. Some recent examples are the works by Plantinga and Scholtens (2001), Hallerbach et al. (2004), Drut (2010), Ballestero et al. (2012), Dorfleitner et al. (2012), Dorfleitner and Utz (2012), Bilbao-Terol et al. (2012, 2013), Pérez-Gladish and M’Zali (2010), Pérez-Gladish et al. (2012, 2013), Cabello et al. (2014), Utz et al. (2014), Calvo et al. (2014), Bilbao-Terol et al. (2015) and Méndez-Rodríguez et al. (2014). Their contents have been analysed and summarized in Table 1 (Note: the heading row of the table refers to the issues that were analysed in the review. They are related to the research and are explained in the following sections).

In this table we can see that although it is common practice to include ESG criteria in the assessment process, it is still unusual to assess weights to the different criteria. When it happens, the weighting mostly consists of a direct assignment. Finally, we have found it is also infrequent to work with stakeholders and, definitely, no research was found in which stakeholders were asked to assess the criteria.

In this work we propose a ranking for mutual funds based on a set of common non-financial criteria agreed by the main stakeholders. The proposed ranking is intended to be a useful tool for those passive investors without a clearly pre-defined socially responsible investment profile or for institutional investors willing to invest in a socially responsible financial product which represents the preferences of main stakeholders.

Because of their features, the most popular investment tool among Spanish investors is investment in mutual funds where all the information is provided by the mutual fund manager (Spainsif 2012). Investors investing in these assets usually are asked to answer a short questionnaire in order to determine their risk profile and then an adequate product is selected for them based on their risk level. Morningstar is a provider of this kind of financial information who gives a simple rating of the funds from one to five stars (see www.morningstar.com).

The purpose of our paper is to provide potential investors with or without financial knowledge with a similar ranking of mutual funds but based on their degree of social responsibility. The proposed ranking does not intend to replace classical financial rankings (e.g. Morningstar ranking of mutual funds) but to complete financial information about mutual funds in order to assist those investors.

Actually, there are a number of self-named ethical or responsible funds, but a few third-party labels exist for identifying socially responsible financial products. The objective of these labels is to serve as a quality standard guaranteeing the systematic integration of ESG criteria into mutual funds’ management. The first European label for SRI funds managed strictly on the basis of Environmental, Social and Governance criteria was launched by Novethic in 2009 (http://www.novethic.com/). Ethibel (http://www.ethibel.be/) also offers a SRI label for European investment funds to guarantee investments only in companies selected based on ESG criteria.

Nevertheless, and despite their unquestionable utility, these labels do not to give sufficient information for responsible investors willing to invest in socially responsible mutual funds. On the one hand the labels make simple classifications such us ethic/non ethic. On the other hand, generally, the labels do not include a complete set of ESG criteria. Therefore, in the European market where more than 1200 self-named SRI funds are available for investors, a ranking of these financial products based on a complete set ESG features would be much more helpful than a particular label. To the authors’ knowledge, only one similar research has been carried out by Tsai et al. (2009). Although they also rank SRI stocks, they do not use CSR data that updates periodically, they do not take into account stakeholders’ preferences and they do not discuss the stakeholder’s different profiles and choices. All this might be useful for designing funds oriented to individual investors.

In this work we have designed a method that proposes a framework of criteria to assess the financial assets. It relies on the opinion of main stakeholders to provide different weights for the different SR criteria. These weights are later used in order to build a composite measure of social responsibility and to rank mutual funds. This nonfinancial ranking provides a parallel classification to the financial one provided by Morningstar.

This information can be of great value for marketing researchers, institutional investors and fund managers attempting respectively to invest or to design in SRI products. The information can also be used by communication managers to develop effective advertising campaigns in order to attract retail and institutional investors.

The remaining of the paper is as follows: in Sect. 2 the methodology for the profiling of stakeholders and the ranking of the funds is presented, in Sect. 3 the application of the proposed methodology to the case study is presented with a broad description of the obtained results. Finally, in Sect. 4 the authors highlight the main conclusions of the work.

2 Proposed methodology

The proposed methodology requires the participation of two types of agents, (i) the facilitators of the prioritization process, (ii) a panel of socially responsible investment stakeholders. In this case study, the facilitators of the process (authors of the paper) have selected the list of Spanish mutual funds to be evaluated and ranked. They have chosen the proper list of stakeholders and have guided them all along the process of weighting the evaluation criteria. With these weights the facilitators will finally evaluate the different funds according to the Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) scores. The methodology is proposed in Fig. 2. A detailed explanation and application of it is presented in the case study section.

2.1 Regarding the stakeholders and their preferences

As pointed out in several recent contributions to literature on CSR, firms’ relationships with society are actually relationships with stakeholders (Clarkson 1995; Maignan and Ferrell 2004; Smith 2003; Ingenbleek et al. 2004). To determine the stakeholders for the SRI funds we have focussed (i) in the literature but also (ii) we have tried to answer the question: who may be interested in the existence of a ranking for SRI funds?

The answer to question (ii) leads us to consider who is demanding and supplying such products. On the supply side, the Spanish National Securities Market Commission (CNMV Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores) says that according to the Spanish Law (2003)35/2003 of 4 November on Collective Investment), in Spain the only possible vendors of such products are:

-

investment services companies or

-

financial entities.

On the other side, not regulated by law, stakeholders would be investors interested in these types of funds. Following the stakeholders identified by Spainsif (2012) and the literature, for this study we distinguish four different groups:

-

Institutional investors, e.g. investing in retirement plans. The most widely mentioned are the Trade Unions (Hamilton et al. 1993; Sparkes 2003). Besides, although public institutions like universities, town halls, public companies etc. buy some Equity Mutual Funds (EMF, the ones of the case study), they mainly invest in bond funds. Therefore, only trade unions are actively using and criticizing EMF.

-

NGOs, e.g. investment as a tool for social action (Sparkes 2004; Sievänen 2014).

-

Individual investors. For these we followed the study carried out in 2012 in Spain by (Méndez-Rodríguez et al. 2014) in which they conclude that SR Spanish investors are likely to be females and, contrary to their initial predictions, they found that the propensity for being socially responsible is not greater for religious investors. They also found that the older the investor the more likely to be socially responsible. This result is similar to that obtained by Beal and Goyen (1998) and Pérez-Gladish et al. (2012) for Australian investors. Surprisingly, the study revealed that Spanish SR investors tend to be lower income investors. We have chosen the stakeholders following these profile patterns.

The above groups would be direct stakeholders, that means, people who directly invest in funds. We have also considered an indirect stakeholder, that is to say, people who may act as facilitators for the investment:

-

Experts in CSR (Academicians, CSR service providers) whose mission is to provide information to groups both of the supply and the demand side (Sen et al. 2006).

These six groups will be profiled by means of our methodology and besides they would be potential users of our ranking of Investment Funds.

2.2 Regarding the evaluation criteria

In his categorization of the responsible investment literature, Hoepner and McMillan (2009) in his widely cited article identifies 14 papers dealing with the definition of criteria for social, environmental and ethical screening in responsible investment. The reporting of information on company performance with respect to environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria has received considerable practical attention. In fact, several rating agencies provide databases which evaluate corporations with respect to a certain number of ESG criteria. Some examples are KLD in U.S., EIRIS in the UK or Vigeo in France. MSCI ESG STATS KLD (known under the name KLD Research & Analytics Inc.) is considered by most of the academic authors the largest and most complete source of information regarding corporate social responsibility (Waddock 2003; Mattingly and Berman 2006).

However, some authors as Chatterji et al. (2009) have acknowledged the low validity of the rating agencies measurement of management systems. In his work they focused on KLD but their conclusions could be extended to other rating agencies. Questioning the quality of the information provided by social rating agencies is not one of the goals of this paper. The main objective is to propose a method to rate mutual funds taking into account agreed weights for the different social criteria.

The KLD system allows companies to be rated according to different social dimensions. Each of these dimensions is evaluated on two criteria, namely strengths and concerns. Strengths and concerns are both rated on binary scales, where “1” signifies “existing” and “0”, “not applicable”. However, the use of binary variables to measure Corporate Social Performance is very rigid and limits the amount of information contained in the evaluation.

Therefore, and in order to avoid the limitations due to the use of binary variables we will work with a different database which is also well known in the SRI field, the Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) database from Vigeo. Vigeo is a leading European expert in the assessment of companies and organisations with regard to their practices and performance on ESG issues. Vigeo has developed Equitics\(^{\circledR }\), a model based on internationally recognised standards to assess to which degree companies take into account social responsibility objectives in the definition and deployment of their strategy. They offer access to ratings in 6 dimensions, which are commonly used by the rating agencies: Human Rights; Human Resources; Environment; Business Behaviour; Corporate Governance and Community Involvement. These six dimensions are broken down into 17 non-financial criteria. A description of these criteria is presented in Table 2.

Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) provides scores from 0 to 100 for each social criterion and also for the aggregated score, thus, it overcomes the problems arisen from the use of binary variables (e.g. KLD).

2.3 Regarding the weighting of criteria

Vigeo’s evaluations for each firm in each dimension (criteria group) are directly summed up into the CSR scores. However, in this way of aggregating they do not consider the fact that the different dimensions or criteria groups might have different relative importance for the investors. In this work we propose to “weight” the different dimensions and to use these weights to calculate the CSR score of each company. We want to stress out that our aim is to demonstrate that when assessing the CSR value of a company there are ways to do it considering the opinion of the related stakeholders. These stakeholders might be the ones we recommend in this study, or they might also be different ones whose opinion is meaningful for the potential investor. Should this be the case, arranging the panel of experts does not need to be so complex. The potential investor could directly address a single expert or stakeholder that aligns with his preferences. Or he could weight the CSR criteria himself following the procedure presented in this paper.

The AHP method is used for weighting the evaluation criteria. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) proposed by Saaty is a measurement theory of intangible criteria (Saaty 1980). AHP is based on the fact that the inherent complexity of a multiple criteria decision making problem can be solved through the construction of hierarchic structures consisting of a goal, criteria and alternatives. In each hierarchical level paired comparisons are made with judgments using numerical values taken from the AHP absolute fundamental scale of 1-9. These comparisons lead to dominance matrices from which ratio scales are derived in the form of principal eigenvectors. These matrices are positive and reciprocal (aij = 1/aji). The synthesis of AHP combines multidimensional scales of measurement into a single one-dimensional scale of priorities.

The method is one of the most extended multicriteria decision making techniques, AHP is being currently applied in the CSR field (Chen and Fan 2011; Tsai et al. 2010), adapts very well to the hierarchy of criteria proposed by Vigeo and also has the additional advantage of being easy to explain to the experts that have to assess the different criteria in a simple and systematic way. More details on the AHP can be found in Saaty (1980), Saaty and Peniwati (2008) and García-Melón et al. (2008).

2.4 Regarding the final prioritization of the funds

Once the main stakeholders, the criteria and the preferential weights have been obtained we will evaluate and rank equity mutual funds (EMF). This will be done in two steps: (i) calculation of the SR Index for each company and (ii) calculation of the SR Index for each fund. We will rely on two different databases: Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) rating and Morningstar’s EMF database. We will adapt Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) criteria to our agreed list of criteria and then, given each firm’s share in each mutual fund we will evaluate and rank the equity mutual funds.

In order to achieve an SRI value for each fund, an intermediate step must be carried out. That is to calculate the SRI value for each of the companies in the investment fund (Eq. 1).

Being:

-

\(\hbox {I}_{\mathrm{jk}}\): Vigeo’ score of the company j for the k criterion

-

\(\hbox {w}_{\mathrm{k}}\): relative importance of k criterion given by stakeholders

-

k: each of the criteria Vigeo uses to assess the degree of social responsibility of the companies

-

Cj: each of the companies

Since the composition of each selected fund is given by the Morningstar database, the following procedure will be applied to calculate the SRI index of each fund (Eq. 2).

Being:

-

\(\hbox {SRI}_{\mathrm{Fi}}\): SR Index for Fund i

-

\(\hbox {SRI}_{\mathrm{Cj}}\): SR Index for Company j

-

\(\hbox {n}_{\mathrm{i}}\): number of Companies included in Fund i

-

\(\hbox {p}_{\mathrm{ij}}\): proportion of Fund i invested in Company j

In order to demonstrate the feasibility and utility of the methodology it has been applied to the following case study.

3 Case study: SR ranking of Spanish mutual funds

3.1 Step 1: select funds’ portfolio

For the selection of the SRI mutual funds (SRIMF) portfolio we will use the Morningstar database. We have focused on large cap equity mutual funds as large companies are more likely to be scanned by social rating agencies. We have considered funds whose region of sale is Spain and whose investment area is Europe since such is the offer in Spain and European companies are more likely to have measured CSR indicators (Lobel 2013). In addition, we have chosen funds whose percentage of equity is more than 80 % because Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) provides data about companies but not about bonds.

Taking into account these restrictions, a total set of 37 funds have been analysed with 925 different companies, some of them belonging to various funds with an average of 44 companies per fund (see Table 3).

3.2 Step 2: identify key stakeholders

As stated above, six main groups of stakeholders have been identified. For our case study two stakeholders have been selected as representatives of each group. In the selection of these representatives we have taken into account their level of expertise in the SRI field, their knowledge of the selected funds, and their willingness and availability to participate in this study. Besides, we have also considered some other personal average data such as: gender, age, etc. according to the reviewed literature (see Sect. 2).

A description of participant stakeholders is given in the Table 4. For some of them it has not been possible to give more details about their names or companies, due to confidential reasons. In brackets we show the gender: male or female.

3.3 Step 3: select evaluation criteria

The selected criteria from the Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) model developed by Vigeo (see Table 2) have been arranged as a hierarchy according to the AHP procedure

3.4 Step 4: weight the evaluation criteria

For the weighting of the evaluation criteria the AHP method was used. AHP requires a hierarchical model of criteria, (see Fig. 3) to pairwise compare all the criteria and to obtain a final weight for them (Saaty and Peniwati 2008). A questionnaire was designed for this purpose. This was conducted through a personal interview with each of the 12 stakeholders. Interviews were carried out either with face-to-face meetings or by videoconference depending on the interviewee’s preferences. First, a set of instructions was presented to explain which comparisons were to be made according to the hierarchical structure proposed and the 1-9 point Saaty’s scale. Last, the surveys were processed using specific software. Weights or relative importance for each criterion and for each stakeholder were derived. A sample of the questionnaire with a couple of the questions stated is shown in Table 5.

In this example, the stakeholder says that, in order to assess the Social Responsibility of a company, Corporate Governance issues are moderately more important than Environmental issues.

All interviews were carried out personally, on the one hand because experts had to understand the research aims, the AHP method and the AHP questionnaires. On the other hand, because all comments and other valuable information experts could give were to be gathered for the research. Interviews lasted around 90 min, the first stage was devoted to the research aims, the method and the questionnaire. The second stage was devoted to answering the 32 questions (comparisons). After processing the answers experts knew if the consistency ratio was below 0, 1, as the AHP method recommends. If it was not the case, experts were asked to improve the consistency of their answers. In the end, all experts showed their satisfaction with the method, stating that it was an explicit and structured procedure for assessing the preferences about the CSR criteria.

Every stakeholder obtained a different set of weights, according to his/her preferences. In order to obtain the global weighting according to all the stakeholders, the aggregation of all the individual priorities by means of the geometric mean was used as suggested by Saaty and Peniwati (2008) and applied in research like Felice and Petillo (2013) or Moreno-Jiménez et al. (2014).

The results obtained are presented in the following Table 6 (see Fig. 4 for abbreviations)

All the stakeholders were offered, on the one hand, to validate their individual results asking them if these really represented their values. According to most of them, the obtained individual results really put forth their inner values. They realised aggregated results and individual ones do not match and, hence, there is ground for discussion and consensus building. However, since consensus building was not within our scope the aggregated weights were the ones used to assess the CSR of the companies.

A graphical comparison of the first level of criteria is also presented in order to analyse the different profiles of the stakeholders.

These results allow different types of stakeholders’ analysis: individual profiles, overall analysis or comparison analysis.

Starting with the individual analyses (Fig. 4a–f), it seems that most stakeholders obtain a predictable profile. For example, G4: Trade unions has given much importance to the dimension Human Rights, Human Resources and Business Behaviour. A similar profile is observed for G6 individual investors, which can be interpreted as the criteria that are more directly related to their interests. However, the dimension Community Involvement has been undervalued even in those groups. Regarding the G1 Saving banks, this group has given great importance to Business Behaviour and Corporate Governance. In the third position they have ranked the Environmental dimension located ahead of Human Resources and Human Rights. Indeed, currently, Corporate Governance, Business Behaviour and Environmental dimensions are receiving the most attention from the companies’ management. However, although G2: Investment services also gives great importance to Corporate Governance and Business Behaviour, they differ with respect to G1 in highlighting Human Rights and not considering much Environment. It seems this group gives more importance to the financial risks associated with Human Rights than with Environment. G3: NGOs, is the one in the demand side that has given more importance to Corporate Governance. Probably, because they are NGOs that trust in management systems. There are NGOs that do not trust much in management systems but they have not been interviewed as they do not influence much the financial economy. Finally, G5: CSR experts also give importance to Business Behaviour, Human Rights and Environmental dimensions but leaves Corporate Governance in the last places. This means that CSR experts give more importance to the operating results than to management activities.

The aggregation of individual profiles in one group (Figs. 5 and 6) allows an overall analysis. As expected, the average results are more balanced than the individual ones, for other examples see [García-Melón et al. 2012 or Spyridakos and Yannacopoulos Spyridakos and Yannacopoulos (2014)]. Finally, the main dimensions are in order of importance: Human Rights, Business Behaviour and Human Resources. These global data contrast with the main issues targeted during the design of ethic funds, as explained in Sect. 1. Indeed, the design processes usually centres around governance and executive compensation issues, and less frequently touch upon the environmental and social stewardship of the targeted companies. However, the aggregation of the stakeholders’ preferences centres on Business Behaviour and Human Rights criteria in this case study. As described in the conclusions, it seems that main business strategies for SR are not fully aligned with the stakeholders’ global preferences.

3.5 Step 5: Prioritization of companies and funds

We have analysed the prioritization results in two ways.

-

(i)

Using the weights of the SR criteria for each individual investor

-

(ii)

Using the weights of the SR criteria according to the whole group of stakeholders. This will be our standard solution

With all these calculations in mind and applying Eqs. (1) and (2) to the Vigeo’s Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) data, the results obtained for the final prioritization of the 37 analysed funds are shown in Table 7:

The obtained values are the result of a weighted sum as explained in Eq. 2. Therefore, each fund can get a value between 0 and 100 depending on the particular values of each company for each criterion (\(\hbox {I}_{\mathrm{jk}}\) in Eq. 1), the criteria weights (\(\hbox {w}_{\mathrm{k}}\) in Eq. 1) and the percentage of the fund invested in each company (\(\hbox {p}_{\mathrm{ij}}\) in Eq. 2). All \(\hbox {I}_{\mathrm{jk}}\) values in the database are positive and thus can be directly added.

The obtained values must not be considered definitive or absolute. On the one hand, the ranking may vary as the companies vary in the Vigeo Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) assessments. On the other hand, funds change their composition continuously and hence the SR Index will vary accordingly. Therefore, the methodology assesses the funds for a particular time span, as long as the funds’ composition last, and as long as the companies maintain their CSR assessments. In addition, it allows predicting how they will perform by changing their composition and, finally, allows calculating performance trends and researching about the evolution of funds’ Social Responsibility.

Discussing the aggregated results, last column in the table, it can be seen that Fund F35 Santander Euroíndice FI is the best ranked followed close by F5 BBVA Bolsa Europa FI. In a second level, there is a large group at a certain distance headed by six funds: F18, F19, F20, F23, F24 and F2. At the end of the ranking three funds rank clearly lower than the others. Those three are the open-ended investment trust funds (SICAV in Spanish), which are mainly devoted to benefits.

Going through the individual results, interestingly the ranking is very robust and there are no significant differences among the stakeholders; i.e., the best and worst funds are similar for every stakeholder (see Fig. 7). There are two main reasons for this coincidence. On the one hand, when in the Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) database there were cells without information, we assigned cero to the cell. That is to say, when for a particular company (j) and a particular criteria (k) Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) had no value in the corresponding cell (\(\hbox {I}_{\mathrm{jk}}\) in Eq. 1), that meant the company had not reported anything, and that was considered a company’s fault to its commitment to accountability and transparency. Therefore, the value 0 fills in the gap for that criterion. Hence, the funds with more companies presenting fewer values have lower SR Indexes.

On the other hand, responsible companies usually perform positively in all criteria and hence, the different criteria weights have a lower than expected influence in the companies’ rank order. Therefore, those funds with more of these responsible companies had better final scores.

Moreover, it is remarkable that the only two funds claimed to be responsible, funds F12 and F36, have not performed particularly well (see Fig. 7). Actually, we have found just two so-called “responsible” Equity Mutual Funds eligible for the study. There is a niche for this kind of funds that could be covered taking into account our research results.

A ranking can be developed to communicate to non-specialist investors the funds’ SR level. It would be a communication technique similar to the black stars of the Morningstar rating used to communicate the funds’ financial performance. We have put forward four levels (see Fig. 8) and have ranked each fund according to the results obtained. Then we have compared them to their Morningstar rating (see Table 8).

As it can be seen in Table 8 the SRI ranking does not match the Morningstar ranking. For example, the best funds for the SRI ranking are F11 and F28 (with four clovers) while the best funds for the financial ranking are F35 and F5 (with four stars). However, numerous investors would not be interested in these rankings considered individually. These investors, when making decisions about their portfolio composition, would take into account both, together with their investment requirements.

4 Conclusions

In this research we have focused on obtaining a ranking of investment funds according to the social responsibility of their companies. The aim is to complement the existing financial tools in Europe. We have applied the proposed methodology to an attractive Spanish case study. In Spain there is a low level of implementation of these products and yet, there is an apparent great potential for the socially responsible investment. A stimulation of demand is required in Spain and it necessarily involves greater information about the supply of these products. The research, hence, not only addresses investors but, also, the companies themselves, fund managers, financial institutions, financial researchers and reporters, marketers and advertisers, etc.

The methodology takes into account the different SR criteria, or ESG considerations. For this, it relies on the Vigeo’s Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) database because of its unique characteristics. Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) assesses six SR dimensions divided into up to 17 criteria.

The procedure allows analysing particular profiles of investors and companies by giving different weights to the SR criteria. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is applied for the weighting. To show the adaptability of the methodology, but also aiming at obtaining a balanced proposal for the criteria weights, a panel of SR financial market stakeholders has been arranged. By means of AHP, their individual preferences regarding Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) SR criteria have shown in the criteria weights and meaningful differences have been found. That is to say, the individual socially responsible investment profiles have been obtained. Therefore, for the case study the different stakeholders’ approaches were aggregated in an average value for the funds’ social responsibility assessment.

In the case study 37 Spanish large cap equity mutual funds were assessed. The criteria weights were applied in a weighted sum to the Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) data for every criteria of every company of each fund. Thus, a social responsibility index was calculated ranking ordering the 37 funds. The ranking was calculated for each individual set of criteria weights and for the set of average weights.

Results showed the dimensions Human Rights, Business Behaviour and Human Resources were the most preferred and hence most weighted. However, they were similarities and differences among the stakeholders that showed their inner values and approaches towards socially responsible investment. Human rights dimension was given the largest importance by all except for the saving banks. Saving banks actually placed all the internal dimensions before the external, i.e., they care more about the closer scope of the company’s responsibility. Also interestingly, while the suppliers: Saving banks and Investment services companies, gave the largest importance to the Corporate Governance dimension, the demanders: individual investors and NGOs, trade unions and CSR experts, left it the fifth dimension out of six.

According to the results, on the offer side Banks seem to understand CSR as an inner driving force while Investment Service Companies seem to see CSR as an external opportunity or risk. This is why the former give more importance to dimensions Human Resources and Environment (understood as management procedures) and the latter give more importance to Human Rights (understood as social stewardship and boycotts).

Furthermore, on the demand side, Environmental issues are given little relative importance. Only CSR experts drew attention to the environmental dimension and it was in the third place. Discussed this fact with the stakeholders, environmental issues are regarded as a natural consequence of the business behaviour. However, in the authors opinion, there is also a social bias in the Spanish SRI market and, hence, the importance of Human Rights and Human Resources.

In conclusion, the research results showed a significant difference between the approaches of the offer and the demand towards SR investment. For that, the proposed methodology can encourage stakeholders to discuss those differences looking for a better understanding among vendors, demanders and opinion makers.

It was observed the companies with better social responsibility performance (first positions in our ranking) provided more information and leaded all the Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) criteria. Hence, the funds including more of those companies had better social responsibility indexes. For that, we can also conclude that our methodology could help funds designers to select those companies in Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) which perform better in those criteria preferred by their targeted investors.

It must be stressed out the final SR score obtained for each fund cannot be considered as a final assessment. The funds vary in composition with time, and also vary the SR performance of companies they invest on. Being based on Equitics\(^{\circledR }\) data, the methodology allows easily updating the SR scores as the funds and companies change with time.

This methodology and its results are useful for the Spanish case that mainly uses the strategy of excluding companies to form the funds’ portfolio. This methodology can be used to establish the minimum score from which the companies are excluded in the funds. Another interesting future application could be the use of the obtained scores in a portfolio selection model where the scores could play the role of cut-off points or thresholds regarding the social responsibility level the investor is willing to assume.

Finally, individual investors are increasingly asking for more complete information, and this includes funds’ SR performance. Be it due to the investor’s consciousness and care about ESG considerations or be it due to a consideration of the investment risks. In both cases the methodology provides complete, understandable and updated information that can be easily combined with other sorts of financial information, such us the Morningstar classification of funds.

References

Ballestero, E., Bravo, M., Perez-Gladish, B., Arenas-Parra, M., & Pla-Santamaria, D. (2012). Socially responsible investment: A multicriteria approach to portfolio selection combining ethical and financial objectives. European Journal of Operational Research, 216(2), 487–494.

Beal, D., & Goyen, M. (1998). Putting your money where your mouth Is. A profile of ethical investors. Financial Services Review, 7(2), 129–143.

Bilbao-Terol, A., Arenas-Parra, M., & Cañal-Fernández, V. (2012). Selection of socially responsible portfolios using goal programming and fuzzy technology. Information Science, 189, 110–125.

Bilbao-Terol, A., Arenas-Parra, M., Cañal-Fernández, V., & Bilbao-Terol, C. (2013). Selection of socially responsible portfolios using hedonic prices. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(3), 515–529.

Bilbao-Terol, A., Arenas-Parra, M., Cañal-Fernández, V., & Bilbao-Terol, C. (2015). Multi-criteria decision making for choosing socially responsible investment within a behavioral portfolio theory framework: a new way of investing into a crisis environment. Annals of Operations Research, published online 31 July 2015, doi:10.1007/s10479-015-1947-9.

Cabello, J. M., Ruiz, F., Pérez-Gladish, B., & Méndez-Rodríguez, P. (2014). Synthetic indicators of mutual funds’ environmental responsibility: An application of the Reference Point Method. European Journal of Operational Research, 236(1), 313–325.

Calvo, C., Ivorra, C., & Liern, V. (2014). Fuzzy portfolio selection with non-financial goals: exploring the efficient frontier. Annals of Operations Research, 1–16.published online 16 February 2014, doi:10.1007/s10479-014-1561-2.

Chatterji, A. K., Levine, D. I., & Toffel, M. W. (2009). How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18(1), 125–169.

Chen, S., & Fan, J. (2011). Measuring corporate social responsibility based on a fuzzy analytical hierarchy process. International Journal of Computer Network and Information Security, 5, 13–22.

Clarkson, B. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analysing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academic Management Review, 20(1), 92–117.

Cortez, M. C., Silva, F., & Areal, N. (2009). The performance of European socially responsible funds. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 573–588.

De Felice, F., & Petillo, A. (2013). Absolute measurement with analytic hierarchy process: A case study for Italian racecourse. International Journal of Applied Decision Sciences., 6(3), 209–227.

Dorfleitner, G., Leidl, M., & Reeder, J. (2012). Theory of social returns in portfolio choice with application to microfinance. Journal of Asset Management, 13, 384–400.

Dorfleitner, G., & Utz, S. (2012). Safety first portfolio choice based on financial and sustainability returns. European Journal of Operational Research, 221, 155–164.

Drut, B. (2010). Sovereign bonds and socially responsible investment. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 131–145.

Eurosif (2012): European SRI study. Available at: http://www.eurosif.org/research/eurosif-sri-study/sri-study-2012

García-Melón, M., Gómez-Navarro, T., & Acuña-Dutra, S. (2012). A combined AHP-Delphi approach to evaluate sustainable tourism. Environmental Assessment Review, 34, 41–50.

Hallerbach, W., Ning, H., Soppe, A., & Spronk, J. (2004). A framework for managing a portfolio of socially responsible investments. European Journal of Operational Research, 153, 517–529.

Hamilton, S., Jo, H., & Statman, M. (1993). Doing well while doing good? The investment performance of socially responsible mutual funds, Financial Analysts Journal 49, 62–66.

Hellsten, S., & Mallin, C. (2006). Are ’Ethical’ or ’Socially Responsible’ investments socially responsible? Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 393–406.

Herzig, C., & Moon, J. (2013). Discourses on corporate social ir/responsibility in the financial sector. Journal of Business Research, 66, 1870–1880.

Hoepner, A. G., & McMillan, D. G. (2009). Research On ’Responsible Investment’: An Influential Literature Analysis Comprising A Rating, Characterisation, Categorisation and Investigation. (August 14, 2009).

Ingenbleek, P., Binnekamp, M., & Goddijn, S. (2004). Setting standards for CSR: A comparative case study on criteria-formulating organizations. Journal of Business Research, 60, 539–548.

Lobel, Sharon. (2013). Predicting organizational responsiveness to poverty: Exploratory model and application to Brazil and the United States. European Management Journal, 31(5), 522–535.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: an integrative framework. Journal Acad Marketing Sciences, 32(1), 3–19.

Mattingly, J. E., & Berman, S. L. (2006). Measurement of corporate social action discovering taxonomy in the Kinder Lydenburg Domini ratings data. Business & Society, 45(1), 20–46.

Méndez-Rodríguez, Bravo-Sellés, M., Galguera, L., & Pérez-Gladish, B. (2014): Profiling Spanish socially responsible investors, 8 June 2014, Available http://ssrn.com/abstract=2447456.

Moreno-Jiménez, J. M., Salvador, M., Gargallo, P., & Altuzarra, A. (2014). Systematic decision making in AHP: a Bayesian approach. Annals of Operations Research, 1–24. doi:10.1007/10479-014-1637-z.

Pérez-Gladish, B., & M’Zali, B. (2010). An AHP-based approach to mutual funds social performance measurement. International Journal of Multicriteria Decision Making, 1(1), 103–127.

Pérez-Gladish, B., Benson, K., & Faff, R. (2012). Profiling ethical investors: Australian evidence. Australian Journal of Management, 37(2), 189–209.

Pérez-Gladish, B., Méndez-Rodríguez, P., M’Zali, B., & Lang, P. (2013). Mutual funds efficiency measurement taking into account financial and socially responsible criteria. Journal of Multicriteria Decision Analysis, 20(3/4), 109–125.

Plantinga, A., & Scholtens, B. (2001). Socially responsible investing and management style of mutual funds in the Euronext stock markets. University of Groningen. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=259238, or doi:10.2139/ssrn.259238.

Renneboog, L., Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2011). Is ethical money financially smart? Nonfinancial attributes and money flows of socially responsible investment funds. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 20(4), 562–588.

Renneboog, L., Horst, J., & Zhang, C. (2008). Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance, and investor behavior. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(9), 1723–1742.

Saaty, T. L. (1980). The analytic hierarchy process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Saaty, T. L., & Peniwati, K. (2008). Group decision making: Drawing out and reconciling differences. Pittsburgh: RWS Publications.

Sen, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Korschun, D. (2006). The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 158–166.

Sievänen, R. (2014). Practicalities bottleneck to pension fund responsible investment? Business Ethics: A European Review, 23(3), 309–326.

Smith, Craig N. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how? Calif Management Review, 45(4), 52–76.

Spainsif. (2012). Socially responsible investment in Spain (In Spanish). Report Spainsif.

Spanish Law 35/2003 of 4 November on collective investment.

Sparkes, R. (2003). Socially responsible investment: A global revolution, Ed. Wiley

Spyridakos, A., & Yannacopoulos, D. (2014). Incorporating collective functions to multicriteria disaggregation-aggregation approaches for small groups decision making. Annals of Operations Research, doi:10.1007/s10479-014-1609-3.

Steuer, R. E., Qi, Y., & Hirschberger, M. (2007). Suitable-portfolio investors, non-dominated frontier sensitivity, and the effect of multiple objectives on standard portfolio selection. Annals of Operations Research, 152, 297–317.

Tsai, W. H., Hsu, J. L., Chen, C. H., Lin, W. R., & Chen, S. P. (2010). An integrated approach for selecting corporate social responsibility programs and costs evaluation in the international tourist hotel. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(3), 385–396.

Tsai, W., Chou, W., & Hsu, W. (2009). The sustainability balanced scorecard as a framework for selecting socially responsible investment: An effective MCDM model. Journal of Operational Research Society, 60, 1396–1410.

Utz, S., Wimmer, M., Hirschberger, M., & Steuer, R. (2014). Tri-criterion inverse portfolio optimization with application to socially responsible mutual funds. European Journal of Operational Research, 234, 491–498.

Waddock, S. (2003). Stakeholder performance implications of corporate responsibility. International Journal of Business Performance Management, 5(2), 114–124.

Zopounidis, C., & Doumpos, M. (2013). Multicriteria decision systems for financial problems. TOP, 21, 241–261.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Melón, M., Pérez-Gladish, B., Gómez-Navarro, T. et al. Assessing mutual funds’ corporate social responsibility: a multistakeholder-AHP based methodology. Ann Oper Res 244, 475–503 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2132-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2132-5