Abstract

This paper describes the processes we engaged into develop a measurement protocol used to assess the outcomes in a community based suicide and alcohol abuse prevention project with two Alaska Native communities. While the literature on community-based participatory research (CBPR) is substantial regarding the importance of collaborations, few studies have reported on this collaboration in the process of developing measures to assess CBPR projects. We first tell a story of the processes around the standard issues of doing cross-cultural work on measurement development related to areas of equivalence. A second story is provided that highlights how community differences within the same cultural group can affect both the process and content of culturally relevant measurement selection, adaptation, and development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In general, community based participatory research (CBPR) is defined as a “collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change” (Viswanathan et al. 2004 p. 3). Fisher and Ball (2003) discuss Tribal Participatory Research, which delineates the unique aspects of American Indian and Alaska Native sovereignty and history. In this paper we provide a detailed description of the process and content issues involved in a collaborative approach between community and university partners in the selection, adaptation, and development of culturally relevant measures for specific cultural populations. While conceptually integral to the CBPR process, there is sparse literature describing the scientific, process, and ethical issues involved in collaborative measurement development. A secondary purpose is to illustrate important community differences in both process and content across two communities sharing a common cultural history.

Overview

Cross-cultural measurement issues inevitably arise in community intervention research partnerships involving western science and nonwestern cultural groups. The resulting dilemmas between contrasting worldviews and epistemologies require discussion and negotiated solutions. Through our experience, we came to appreciate how measurement development in an intervention project with indigenous culturally distinct groups can serve as a flashpoint where different values, worldviews, and meaning systems associated with two cultural knowledge systems converge. One knowledge system is embedded in the culture of the community—in the current case, this involved the cultures of two Yup’ik communities, both of which possessed a deep and rich indigenous cultural knowledge system, along with additional more local knowledge and customs that were unique to each community. The other system is based in the culture of Western intervention science, manifested in issues of funding, timetables for task completion, measurement, and research design. Much of the work we describe here involves an intercultural encounter between these knowledge systems. This encounter involved a negotiation about measurement and measures in which academic and community partners navigated deeper waters of shared understanding. In so doing, underlying issues surfaced of practical and conceptual significance to the larger project.

The primary story of the paper involves many of the issues now generally recognized to arise in cross-cultural measurement development work (Allen and Walsh 2000), such as construct equivalence, contextual relevance of item content, item wording, and sometimes subtle issues in linguistic equivalence, including local variations in English language dialect and usage. However, in our project, the collaborative process also led to construct elaboration and a rethinking of aspects of our underlying theoretical framework. In this process, some original measures were discarded and new measures created. These will be discussed in detail in subsequent pages.

A secondary story involves how the measurement development process may confront not only cultural challenges but also differences among communities sharing the same broad cultural heritage. While individual cultural differences among members of the same culture have long been recognized in the cultural psychology literature (Berry et al. 2002), community differences among groups sharing a similar culture are less appreciated and seldom explored (Birman et al. 2005). In the current project, differing recent histories of suicide in the two communities affected discussions and decisions regarding the priority given to and acceptability of direct measures of suicidality. Thus, measurement development is not only a technical process; it also occurs within a context of local cultural history. Approaching this process from a CBPR perspective helped provide a portrait of how culture, methodology, and collaboration can intersect in the service of science as well as communities.

We begin by describing the scope of existing research on the role of culture in doing measurement development work. With this as groundwork, we then describe the collaborative process we shared with our community partners in developing measures for a cultural intervention program promoting protective factors in the prevention of youth suicide and alcohol abuse.

Culture in Measurement Development and the Culture of Measurement Development

While the pervasive role of culture and its influence on the functioning of measures is now widely recognized (Vinokurov et al. 2007), understanding the role of culture in measurement development work is less fully advanced. In particular, literature on the processes involved in creating or adapting measures for research with Alaska Natives and American Indians is extremely limited. As Smith et al. (2004) note, “Although some of the extant literature on survey research with Native Americans has mentioned the importance of addressing the issues of cultural sensitivity and appropriateness in survey development and implementation, the research is sparse in terms of providing detailed description of these surveys and methods used for survey development” (p. 71).

Despite these limitations, existing work provides a general contour of the issues encountered and efforts to accommodate them. This work includes three main emphases: (1) technical issues in measure development distinct from the statistical approaches to establish construct equivalence; (2) intergroup processes involving researchers and community members in the measurement development process, and (3) aspects of the cultural/community context in which constructs are selected and measures developed. Together, these three areas of emphasis suggest that developing, adapting, and translating measures across cultures involves far more than the psychometric issues in establishing equivalence (Vinokurov et al. 2007). As Weaver (1997) states: “without culturally specific knowledge integrated with self-awareness and research skills the researcher may have difficulty framing appropriate questions, developing relevant approaches, implementing projects, and interpreting data in a meaningful way” (p. 2).

Culture and Technical Issues in Measure Development

Here, technical issues refer to cultural influences on decisions ranging from the choice and cultural relevance of instruments to more discrete issues such as response anchors and wording. Several papers describe the host of cultural issues involved in adapting and creating measures in diverse cultural contexts. For example, the decision to use self-administered questionnaires rather than interviews was explored by Solomon and Gottlieb (1999). Their pilot test of the two formats resulted in no substantive differences in the information obtained. Because of the private nature of some of the information, they chose self-administered questionnaires, with interviewers available to answer any questions. A similar format issue was confronted by Smith et al., (2004), who opted for face-to-face rather than telephone interviews to remain more congruent with local oral communication traditions.

Christopher et al. (2005) addressed cultural issues in the way they constructed the manual to guide their interviews. Specific issues included the necessity to explicitly ensure confidentiality of interviews, that information shared in the interviews would stay in the community, and that the purpose of the research was to generate information to improve Apsáalooke women’s health. “Apsáalooke women who worked with the training manual wanted these points to be addressed openly, because they are areas that have been problematic in past research with Native Americans; however, these concerns are not typical of those discussed in the development of most interviewer training manuals and practices in the majority culture” (Christopher et al. 2005, p. 416). They additionally addressed the issue of gender of interviewer and how the interview should be introduced through the Apsáalooke custom of introducing yourself “by saying who your family is and where they come from” (p. 416). Such a practice differs from the more neutral introductions found in many interview guides.

Linguistic aspects of measure development and adaptation have been discussed as well. In translating measures into four different Slavic languages, Vinokurov et al. (2007) describe the importance of using simple sentences, active voice, and descriptive phrases to proactively define potentially unfamiliar words. In addition to efforts to achieve clarity of meaning, they also avoided metaphors and colloquialisms not readily transferable from one culture to the other. This was accomplished collaboratively with cultural consultants, who focused on such issues as word choices, grammar, syntax, and differences in the underlying meaning of words in diverse cultures. “In the process of addressing such myriad issues, the whole translation process became a qualitative approach for the instrument development that maps contexts of people’s lives, fosters collaborations, and documents emic-etic aspects of research” (p. 12).

Sequencing, content of questions, and wording issues have also received attention. With respect to sequencing, for example, Smith et al. (2004) describe collaborative discussions with community representatives of a Native American community about where to include demographic questions in the research protocol. “Questions asking for demographic information, which survey research experts recommend placing at the end of surveys because of their personal nature (Suskie 1996; Weisberg et al. 1996), were placed at the beginning as these questions were viewed as less personal than the health questions” (p. 73). With respect to content, these researchers excluded questions asking women to report on their personal sexual behavior, even though it is a risk factor for cervical cancer, the focus of their study. “Native women on our staff and on the advisory board stated that this line of questioning is not appropriate in the Apsáalooke culture. Women probably would feel uncomfortable with questions on sexual behavior and perceive them as too bold, direct and disrespectful of their feelings” (p. 74). With respect to wording, Stevens et al. (1999) found that “Because it is intrinsic to many American Indian cultures to think and speak in a positive way and to avoid thinking or speaking in a negative way, questions that elicit negative thinking are inappropriate (p. 779S)”.

Finally, issue of language choice used in the measures and with participants has been discussed. Christopher et al. (2005) suggest that “Because of the predominantly oral nature of the Apsáalooke language, it would not have worked to translate the interview into Apsáalooke and have the interviewers read the script. It would also not have been culturally acceptable to ask the participants to speak only in English. In the training manual, we suggested that it might be necessary for the interviewers to interpret the questions from English into Apsáalooke. We added that interpreting would help the participants to better understand certain questions, allow them to feel more comfortable, and provide a more effective means of communicating for both women” (p. 418).

Thus, existing literature on measure development places the entire process of developing measures within a cultural context. Measurement development efforts must be responsive to cultural practices. In Native communities, this includes the format for gathering information, how data gatherers introduce themselves and the task to participants, issues of confidentiality, attention to what constitutes respectful behavior and appropriate topics to ask questions about, and issues related to item sequencing, wording, and content. The present study adds to this emerging area through a careful description of the procedures we used in our measurement development efforts, some of which involve the same kinds of issues in the extant literature. However, the issues of construct elaboration and how decisions are reached to discard some measures and create new ones are not readily available in this literature, while they are central to the story told here.

Intergroup Processes Involving Researchers and Community Members

With respect to intergroup processes, there is unanimity in the CBPR literature about the importance of approaching measurement development as a collaborative process that involves both academic and community representatives. Such a perspective must be “based on trust, respect, caring, critical reflection, and active participation, which aid in the development of conceptual definitions and measures that are congruent with respondents’ experiences and contexts” (Vinokurov et al. 2007, p. 4). Because such collaborations affect the outcomes as well as process of measurement development, the dynamics of their creation and evolution over time are important to document.

Measurement development processes and relationships also reflect broader collaborations around the larger projects within which measurement development is embedded. For example, Pinto et al. (2008) interviewed African American and Latina women involved in their participatory research work. They found that researcher long term involvement in the community and spending time getting to know the community were high on the list of trust-enhancing aspects of the research relationship. These actions, in turn, served as preconditions for meaningful measure development collaborations. Christopher et al. (2008) view the issue of trust as extending beyond researchers and ongoing community collaborators to include initial collaborators and the greater community. The degree to which these initial community partners are seen as committed to their community is an important factor in creating project credibility. Thus, while measures may be developed in collaboration with select community representatives, it may also be important to gauge broader community acceptance of the work. The current project reports on this process and validates its importance.

The normative process for collaborative engagement described in the literature is some variant of a local advisory board. Local advisory boards serve as cultural consultants around measure development. They typically review item content, providing input on both substance and wording (e.g. Smith et al. 2004; Stevens et al. 1999). They can also be engaged more broadly in the selection of measurement variables and elaborations of the broader dimensions of culturally congruent theoretical constructs. Vinokurov et al. (2007) underscore the importance of working with diverse, committed representatives of the cultural communities involved, who can more completely represent the ultimate consumers of the measures developed (see also Legaspi and Orr 2007).

Discussion in the literature of the actual processes involved in these conversations is scant, however. Stevens et al. (1999) report that, over time, individual and tribal differences within their advisory group necessitated both group and individual discussions of cultural issues in measure development. Legaspi and Orrs’ (2007) collaborative work with an intercultural data dissemination team also provides several examples of the critical element of responsiveness to local concerns.

However, additional process accounts are needed to further our understanding of such broader questions as how conflicts among collaborators are dealt with, how to balance scientific concerns with local ones, and how the moderating role of trust develops and functions when differences arise. The present project provides additional insight into some of these relatively neglected intergroup issues involved in collaborative community intervention work.

The Cultural Surround of Measurement Development and Interpretation

The kinds of issues discussed in the previous section occur in the broader context of cultural and community history, norms and traditions, and experience with the substantive issue on which the intervention focuses. Current research suggests that such aspects of local culture influence a range of issues associated with measurement development and implementation. For example, in some cultural contexts, the mere mention of a topic may invoke the belief that this increases the chance that the event may occur. With respect to Native Americans, several authors involved in cancer prevention interventions reported that one of the issues affecting how interventions were developed and assessed involved a local reluctance to talk about cancer for fear of bringing the disease on oneself (Smith et al. 2004; Solomon and Gottlieb 1999). Similar cultural taboos were found among immigrants from the former Soviet Union (Dohan and Levintova 2007) namely, that information about the diagnosis of cancer should be withheld from the person and indeed not be discussed in the community. In this community cancer was seen as a “death sentence”, an incurable condition that can rob the afflicted person of their spirit and will to live.

The acculturation status of Native American/Alaska Native communities has also been cited as an important cultural influence impacting the functioning, utility, and appropriateness of measures. In a study of the relationship of tribal identification to attitudes about screening for cervical cancer, Solomon and Gottlieb (1999) assessed tribal identification through American Indian blood quantum, blood quantum for the primary tribe, and a self-report traditional behavior scale. In analyzing their data, they concluded that “the intention of the program and the community’s history of acculturation must be taken into consideration. In a remote reservation community, a simple blood quantum measure may be sufficient, but in a community with a long history of exposure to mainstream culture, the traditional behavior scale may offer more detailed information regarding language or other health behavior barriers or facilitators” (p. 502). Dana (2005) also emphasized how acculturation status can function as an important moderator variable in the interpretation of the meaning of any measure. With respect to language per se, Legaspi and Orr (2007) found that older generation Yup’ik knew more Yup’ik than English while younger people tended to know both languages, or were monolingual English. Because some of the English words had no Yup’ik equivalent, it was necessary for a bilingual communicator to provide examples in Yup’ik. Together, these papers suggest the importance of understanding not only cultural norms and history, but also the local meaning of constructs and the overall acculturative status on the level of the community.

Technical Issues, Intergroup Process, and Cultural Surround in Elluam Tungiinun/Yupiucimta Asvairtuumallerkaa Measurement Development

The measurement development process described in this paper occurred in the two rural Yup’ik communities previously described (Ayunerak et al., this volume). This work built on the People Awakening project (Allen et al. 2006; Mohatt et al. 2004a, b), in which an indigenous theory of protective factors for alcohol abuse was generated through life history interviews of 101 Yup’ik adults. This model identified proximal protective factors at the individual, family, and community level and was extrapolated to adolescent alcohol use and suicide prevention for the present project (see Allen et al. this issue, for rationale). The current paper is a process description of the collaborative measurement development effort. Fok et al. (2011a, b) provide a technical description of the final measurement model, while Allen (online Appendix S1) provides detailed description of more technical aspects of the process and content issues.

The core research team for the overall project was composed of the paid Yup’ik community co-research staff and university-based faculty and staff, some of whom were also Yup’ik or members of other Alaska Native and American Indian tribal groups. Core research team meetings generally consisted of about half community and half university co-researcher staff. Meetings were conducted face-to face at the university and in the two remote communities in southwest Alaska in which the project was based, as well as through audio and video conferencing hosted by the university. In addition to cultural and linguistic experts, relevant consultants included educational experts and teachers, external research consultants, behavioral health providers, and Alaska Native Studies and Alaska Native language faculty.

The measurement development group was a subset of this larger group, with different research staff and consultants, depending on the expertise needed to address the question at hand. This group would meet frequently during the week to divide up, monitor, and complete varied measurement development tasks to be described more fully later. Often additional individual meetings with cultural experts would also be held on specific topics such as the meaning of a particular cultural concept or how to deal with a particular issue in item wording. The pace was intense, such that in any two-week period, in addition to weekly project meetings, several meetings might also be held with the smaller measurement development group.

Reviewing the Initial Measurement Model: Measure Selection and Refinement

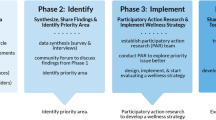

The processes and decisions related to measurement development took place over a three-year period. Figure 1 outlines the various primary tasks at different times in this period. Most of the first year of this process involved an assessment of the appropriateness of the overall model developed with Yup’ik adults, a literature search to identify potentially comparable adolescent measures of the individual, family, and community level protective factors in that model, and item review of candidate measures. The selected scales covered a wide range of constructs, items, and response formats, each of which were candidates for review by the committee.

The initial impact of the collaborative process on the overall model was felt immediately, as the appropriateness of some of the constructs in the adult model were questioned with respect to Yup’ik youth. Asking youth about trauma, for example, was seen as too culturally intrusive, and directly questioning youth about suicide ideation and alcohol use was seen as culturally inappropriate. After considerable discussion, the trauma measure was dropped entirely, while the assessment of alcohol use was agreed to. Considerable discussion surrounded whether and how to assess suicide risk. The two communities and the co-researchers from each disagreed with each other about whether suicide risk should be assessed at all. In addition, concern was expressed about how directly or indirectly at approach suicide risk if it was to be measured. An external consultant was strongly encouraging its direct assessment through the Suicide Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ-Jr; Reynolds 1988), while community co-researchers found that approach too intrusive. Considerable discussion and debate continued over several months and meetings, and the issue of whether and how to assess suicide risk was not resolved until much later in the project, as will be described later.

Cultural Adaptation of the Measures

After this initial review of the model and reviewing the literature for potential new adolescent-appropriate measures, a final list of measures was selected. Some measures, such as the Family Social Network and Family Protective Factors scales, were developed in prior work with Yup’ik adults (Mohatt et al. 2004a, b), while others such as the Self-Mastery scale (Pearlin et al. 1981) were developed in non-indigenous populations.

Overall Item Refinement Process

Working with a team of cultural experts representing both university and community members, each scale was then reviewed at the item level to maintain linguistic equivalence, comprehensibility, and cultural relevance/appropriateness of original items while rewriting them to be understandable to local youth. If this was not possible, we reworded the item to describe a contextually relevant and culturally appropriate behavior functionally equivalent to the original item. A few items were deleted because no comparable rewrite could be agreed upon. On most scales much of the original item content was retained, though a significant number of items were modified for linguistic and contextual equivalence. The scale requiring the most modification was the Family Environment Scale (Moos and Moos 1994). Here, issues of wording or potential meaning of items most clearly reflected deeper cultural differences between Yup’ik families and those with whom the scale was originally developed with respect to the expression of emotion in families and to family interaction patterns more generally. Examples of issues that arose are presented below.

Linguistic Equivalence

These issues reflected the local English language dialect of Yup’ik community members, a dialect embedded in Yup’ik language grammatical construction, local word choices in English usage, and sociolinguistic conventions (Jacobson 1998). For example, one item on the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos and Moos 1994), “We really support one another” was modified to “In our family, we help and support each other” to clarify that specific meaning of “support” in this context did not refer to physically supporting or aiding one another. Another item, “We often criticize each other” was subsequently modified to “In our family, we often put down each other” to reflect local dialect and preferences in word choices not readily apparent to outsiders.

Comprehension of Items

Several concerns were expressed regarding confusion created by reverse keyed and negatively worded items. For example, one item on the FES, “We are rarely openly angry at each other” represented a complex linguistic translation around responding “yes” or “no” to an item that included the juxtaposition of “rarely” and “openly.” This item was rewritten as “We lose our tempers a lot,” which reversed the keying for scoring but made the intent of the item more readily understandable to community members.

Contextually Irrelevant/Culturally Inappropriate Items

The group also identified some items as contextually irrelevant in rural Alaska communities (e.g., “driving in a car,” “shopping in the community” is not done in communities off the road system with one or two small general stores). An example of a culturally inappropriate or confusing item was the FES statement “In our family, we try to outdo each other.” Our local cultural experts suggested that in Yup’ik culture, such openly competitive behavior among family or community members is so culturally inappropriate that the question itself would be inappropriate to ask.

Pilot Testing

After conducting this revision process, we piloted the revised items and scales with 18–20 year old Yup’ik freshmen recently arrived to the University from rural Southwest Alaska communities. These students completed the survey items individually or in small groups and then participated in debriefing interviews to provide feedback on readability, understandability, and cultural appropriateness. A modified cognitive interviewing approach (Willis 2005) was used to elicit the sources of misunderstandings in the items that were linguistically confusing.

Construct Elaboration: Developmental Adaptation, New Measures, and a Refined and Extended Theoretical Model

In addition to the issues that arose during item adaptation of the initial set of instruments selected to assess the model underlying the intervention, the close and ongoing consultation with cultural experts, external consultants, and the pilot work led to several more far-reaching recommendations for revision of both the measures and the measurement model itself. These efforts, beginning near the end of the first year of the project, encompassed construct elaboration, the development of new measures to tap culturally nuanced elaborations of constructs, and, importantly, an eventual refinement and extension of the underlying theoretical model to reflect the cultures of the communities in the present study.

From Adults to Adolescents

Because several of the measures were developed for use with Yup’ik adults, the shift to an adolescent population necessitated a developmental revisiting of the constructs as they applied to Yup’ik adolescents. For example, discussions suggested important differences in the construct tapped by the Communal Mastery scale (Hobfoll et al. 2002) among youth in comparison to adults. Here, communal mastery in adolescents was seen as being differentially expressed in relationships with family and friends. Thus, we authored parallel Family and Friends subscales with the same item content to explore possible differences and more fully and appropriately describe the construct. We also adapted an Alaska Native adult measure (Mohatt et al. 2007) as a youth-specific measure to assess negative consequences of drinking that rural Alaska Native adolescents experience.

Community co-researchers also described the nature of adolescent community protective factors as differing from those found in the adult model. We thus developed a more multidimensional assessment of specific community protective factors relevant to the experience of contemporary youth. Specifically, we added youth-relevant community factors such as perceived support, safety, alcohol behavior limits and norms, and opportunities for substance free culturally relevant activities. Thus, one function of the collaborative process was to delve more deeply into the local cultural and developmental meaning of key constructs the intervention addressed and their specific relevance to youth.

Developing New Measures

In addition to revising existing measures, discussions among the measurement development group resulted in efforts to create several new measures designed to capture youth-specific protective factors or mediators of the effects of protective factors. For example, we developed an Alcohol Quantity/Frequency/Binge Episode (Q-F-BE) measure that distinguished episodic binge use from frequency of daily or typical use, a distinction emerging from work with our Yup’ik co-researchers. With the guidance of community team members, we generated items measuring home brew and bootleg alcohol usage (sale and possession of alcohol is illegal in the rural Alaska communities in which we work) to track both amount consumed in situations without containers and settings of both “usual” and “binge drinking.”

Refining and Extending Theoretical Model

The eventual set of measures emerging from these elaborate efforts to adapt existing instruments and create new ones resulted in a modification of the initial adult conceptual model to one fitting the local circumstances of Yup’ik youth. The concept of mastery was expanded to differentiate family and friends; new measures of community protective factors replaced community readiness as a proximal community outcome, and the alcohol use measure was altered to be more meaningful to adolescents. In addition, measures of peer effects, alcohol attributions, and learned optimism were added as intermediate variable outcomes.

Culture, Community, and a Broader CBPR Review Process

After the measurement development process was completed, we held a four day workshop training together with the entire community and university co-research staff to initiate the implementation phases of the project. The meeting was to conclude with a review of the measures by the entire team. Given the distances and expense of travel to rural Alaska, this was the only time during the measurement development process that the entire community and university co-research team came together in a face-to-face format. This larger research group included members of the community co-research team who had never seen the measures because they had been working on other aspects of the intervention, such as the development of intervention activity modules. In addition, as most of the measurement development work was conducted through a sequential focus on one set of scales at a time, many of the community co-research staff were seeing the full set of measures together for the first time.

The review of measures was accomplished by asking all the research team members to complete the full set of measures and reflect as a team on the overall outcomes assessment process as well as contents of specific items and scales. Given the extensive work and involvement of multiple community members, cultural experts, and university co-researchers in the measurement development process, the university co-researchers anticipated that community members would endorse the measures as both relevant and also notably different from the standard questionnaires to which they may have had previous exposure in terms of relevance, wording, brevity, and format.

The initial reaction of our Yup’ik community co-researchers, however, was quite different from these expectations. When the measures were put together as a package, community co-research staff voiced serious reservations about both the cultural appropriateness and lengthiness of the assessment package. The entire survey was seen as too long, too burdensome, and inappropriately intrusive. After engaging in an intensive discussion where the university co-researchers listened intently, we decided to break for the day and reconvene in the morning. At that point, it was unclear if community representatives would give permission to use these measures in their communities despite our lengthy and inclusive process of developing them.

The next morning began with discussion and debate among Yup’ik community members about the appropriateness of asking youth first person questions. Some community members felt youth who were more Western assimilated could respond directly and appropriately to those questions—others felt that the more traditional Yup’ik youth would maintain the cultural value of not feeling comfortable responding individually to first person questioning, thus limiting the validity of their responses.

This concern with first person items seemed more relevant for certain constructs than others. For example, community members agreed that in the Communal Mastery scale, first person questions were appropriate because many of the questions were linked to other people and conveyed a collectivistic tone (e.g. “Working together with family I can solve many of my problems”). It made cultural sense to community members to ask if a youth’s success or difficulties were tied to their family or community. However, the topic of first person questions emerged with the greatest concern in the assessment of substance use and suicide. In the context of community co-researcher concern about the potential intrusiveness of asking directly about suicide ideation, the measurement development committee had proposed an indirect measure of suicide risk, the more positively oriented Reasons for Living Inventory (RFLI; Linehan et al. 1983). This measure was not at issue. Rather, the newly added Suicide Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ-JR; Reynolds 1988) caused concern. This measure had been suggested by external consultants on the basis of its conceptual importance to the model. Though community co-researchers on the measurement development working group expressed initial concern about the measure, members of the working group were eventually persuaded by the arguments of the consultant and the university co-researchers that the inclusion of the SIQ-JR would significantly strengthen the potential findings of the research regarding program effectiveness. In addition, the SIQ-JR had a prior history of use among American Indian communities (Dick et al. 1994; Novins et al. 1999).

Beneath this discussion of the advisability of asking first person questions about suicide and alcohol use were cultural beliefs regarding a profound respect for the person and how such intrusive questioning seemed to violate this respect. In addition was a belief about the power of words, and how their discussion might increase the likelihood of their occurrence. In traditional Yup’ik understanding, things like suicide and alcohol use have a spirit essence, and to speak of them can “feed” the spirit, making it more powerful. The issue of whether and how to assess both alcohol use and suicide risk, first raised and seemingly resolved in the measurement development group, was raised anew by this larger group. The community co-investigators’ concerns did not reflect a denial by youth of alcohol use and thoughts of suicide in their communities; rather they reflected a cultural, and more specifically, local community concern about just how direct we would be with youth involved in the prevention program.

It was here that the depth of local community difference began to emerge with respect to measurement strategies. The two Yupik communities in our prevention projects differed greatly in their respective histories with suicide. In one community, suicide was one of the most important behavioral health concerns, having been a virtual “epidemic” over the years. For example, in the 36 months prior to our engagement with this community, there were 12 suicides reported, recalling a similar devastating cluster of suicides that occurred in the community about 25 years prior. In stark contrast, the second community had not experienced any suicide in over 25 years. Consistent with the cultural belief expressed above, our co-research team from the second community believed that this spirit had not visited their community, but exposing their youth to the thoughts of suicide could constitute such an invitation.

In the context of this history, it was understandable that the community research team from one community wanted to be very direct in asking youth and family members about suicide, while the research team from the other community was very reluctant to do so. They were not saying we should not assess alcohol use or suicide risk, but that we needed to be very careful in how we conducted such assessments. These discussions served as a very important opportunity for the community co-researchers to educate the university collaborators on the intricacies of community and culture, to share with university collaborators the needs and desires of community members for their community, and to actively shape the decision making process regarding the assessment protocol.

Given the level of concern, discussion initially focused on the possibility of other approaches to evaluation, such as non-obtrusive social indicators, key informant approaches, and qualitative methods. University co-researchers were concerned about the extremely limited availability and accessibility of social indicator data as well as the scientific credibility of key informant and qualitative approaches in the current culture of science. However, after reviewing and rejecting available alternatives to self-report instruments, the university co-researcher group offered to rework all the existing instruments in order to delete objectionable measures, delete objectionable items from measures we retained, and substantially shorten the remaining outcome assessment instruments.

This solution was an important systemic event (Kelly 1970), both as a listening and learning process for us and as an exemplar of the issues involved in honoring the collaborative process underlying our work. However, the broad cultural issues and community differences involved in these discussions would surface once again in subsequent meetings with the Yup’ik Regional Coordinating Council (YRCC). Because of its importance, in the section that follows, we explore this more deeply, providing analysis of it as event in system and describing the process of its resolution.

Every Yupik Community is Different: Honoring Community Difference

Because we were collaborating with two communities, with plans to extend the interventions to other communities, the YRCC was established as an oversight council that could provide guidance and coordinate efforts across multiple communities. The YRCC consisted of members of the intervention communities as well as prominent Yupik members of several additional Yupik communities. The Yukon Kuskokwim Health Corporation (YKHC), the Alaska Native regional health corporation providing health services and tribal oversight of health research in the region, identified these individuals as respected and well-known community leaders and Elders who had reputations for working to improve health outcomes in the region and in their respective communities. Several of the YRCC members had some previous experience working on research and service projects.

Subsequent to the above described research team meeting, toward the end of the second project year, our co-research team (university and community co-researchers) developed and provided a formal presentation of the prevention projects from each community to the YRCC. As part of this, we told the story of the partnership processes we engaged in with the two communities and the university and how we were working through the concerns of assessing alcohol use and suicide ideation with each community. We asked the following questions of the YRCC: Are we asking the right things in our questionnaires? Are we asking the right way? Should we be asking other questions? Should we be asking about suicide and how do we ask about suicide? How do we, as researchers, balance community acceptability with the rigors of Western science to show if something is feasible and/or effective? Although we had already engaged the current communities in these questions and processes, we were seeking additional Yup’ik cultural knowledge and wisdom at the regional level and were genuinely interested in engaging more communities in the region.

In the Yupik cultural way, YRCC members engaged each other and our research team with a mixture of narrative stories, discussion, and debate about the concern and relevance of alcohol and suicide in their communities and the region. While there was consensus on the importance of these projects and the need to develop prevention programs, the YRCC felt it was important to revisit and further explain their thoughts on the issue of measuring intervention outcomes. The fundamental notion of measurement was not a Yup’ik concept. “I don’t think Yup’iks measure anything,” said one YRCC member. However, they understood that indicators of community change were critical to both the university co-researchers and funding agencies. Thus, the discussion of differences between the culture of the community and the culture of science was inevitable.

From the community perspective, there seemed to be two important concerns: (1) the continuing struggle to balance a desire to make positive changes in their communities and the reluctance to burden youth and possibly offend spirits through asking direct questions on instruments; and (2) the accountability felt toward Elders present at the YRCC along with other cultural peers in the communities, whose wishes and concerns would be critical in resolving the differences surrounding the issue of measurement. The following quote from a community co-researcher exemplifies these sentiments:

Community 2 co-researcher: That argument [about accountability and measurement] doesn’t happen with just you, but with us. What do the Elders want us to know? The pressures are here now. …There is a constant argument in our head. The Elders are the resources out there. We need somebody to make us stop and say “Ok, this is what I see”. And make us see, but then say, do something about it. That is what this program is saying to me. …You get funds by demonstrating how you are going to measure something. Ok, do it that way, but then the next time you ask for more funding, you might make a suggestion. I don’t mind the discomfort, just so long as we go ahead. I see what this program, and project, can do. We are strong people. We will get over whatever happens. I want to be Yup’ik, I value my heritage, I value the things that make my people who they are. I want to see strong people.

Our community colleague was expressing the sense of compromise between the two cultures involved by suggesting the addition of community Elder groups and other local informants to the measurement model. Doing so, even in the future, would moderate the concern about the burdens of the project related to scientific rigor and include local wisdom. But, importantly, he was drawing critical attention to how university research and funding processes work—and really saying this may not always be best for the participating communities. As was customary in traditional Yupik ways, final decisions were not reached in one sitting, and the first meeting ended with members needing to ‘reflect” on the issues discussed.

At the next YRCC meeting, the more general issues of measurement and co-learning were replaced by specific concerns about the key issue of assessing suicidal ideation. Here the tension included not only differences in the culture of science and of the communities involved, but of different values within Yup’ik culture itself. Elders shared stories with the group about two Yupik cultural values: not talking about suicide and about the importance of and therapeutic utility of talking about issues and concerns. One respected Elder talked about the “taboo” of speaking about suicide, but also expressed the belief that Yupik people used to always find value in talking about their concerns—and how this was one of the ways that people found relief, solutions, and growth when experiencing difficult times (Wolsko et al. 2006). Other YRCC members supported these ideas and began to apply this value to talking about suicide. As the discussion unfolded, many of the YRCC members and community co-researchers seemed to agree that the effects of suicide were at unacceptable levels and it was time to apply this value of talking about their issues to talking about suicide, despite the “taboo” around it.

Community 2 Elder: The topic of suicide is never really discussed in our communities and it never happens in our family. We have gotten used to it that it happens in our community.

Community 1 Elder: Suicide happens, you get traumatized by it, and after a while you forget until another happens. Sometimes people try suicide just for attention.

Community 2 Elder: Somewhere the suicide topic will be presented to the community.

UAF co-researcher 1: If the committee and the community were to agree then this would be one of the measures that the project uses. What we could expect from the modules to focus on this.

Community 2 Elder: I’ve never seen questions like this asked directly.

YRCC Member: Is this going to be in the surveys?

UAF co-researcher 1: That’s what I’m asking and if we can put it in the survey and is this something you are willing to consider or this is taboo and something we don’t do.

Community 1 co-researcher: I think this is the only way.

YRCC Elder: Last month we had a workshop in [community name] and we had a heavy topic one morning and one woman said we don’t want hear it and she stood up and started crying. This morning when I got up I thought of this young man–he is positive and energized and we need one young man who is positive and pushing forward with energy. All of you people have points. If we didn’t care we wouldn’t be here–we come and volunteer yourself. We could be out taking care of grandchildren and he volunteered to be here. The people from Fairbanks could be elsewhere. Being here we recognize them and we are thankful.

Community 1 Elder: What about what the Elders always say? Like [person’s name] was talking yesterday we are traumatized momentarily and we forget it and it is passed and our Elders always say unless you talk about something it is never going to get better. But if you talk about it, it kind of opens it and it gets better. We talk among ourselves and we sometimes feel better after we talk about it. [Two community names] had chain reaction of suicides and it was hard to talk about it and once it got talked about it seems to have gotten better. And we have helped people to get better with healing circles and the hurt doesn’t stay with you for many years.

While there was consensus among the YRCC that suicide was a serious behavioral health concern, the Yup’ik cultural value of not talking for others led to the decision that suicide should only be included in the assessment procedures if the local community saw it as acceptable and relevant.

Community 2 co-researcher: The approach we are taking is [a] community participation angle. There are lots of issues out there that are hard for people to talk about…. The thing about the approach that I appreciate is that you are willing to give it to the community. That approach works. And [person’s name] talking about his impression in 5 months there is change. Maybe there is the change because they were already in the frame of mind. Questions like that, let them decide in [two potential communities named], give it to them. Here are the questions and how do you want to do it. Let them decide.

With this understanding, we were able to proceed with the next steps of the intervention.

The final decision made by the YRCC and our research team was not to assess suicide ideation directly, and to not use the RFLI, but to instead develop a new measure of an aligned construct based on significant adaptation work on the RFLI. We ultimately termed this measure Reasons for Life, which, rather than asking about suicide, tapped beliefs and experiences that make life enjoyable, worthwhile, and provide meaning in life. We viewed this construct as a protective factor from suicidal ideation. Thus, through the CBPR process we learned that risk factors identified at the population level had different implications within diverse communities of the same cultural population. This, in turn, had significant implications for measurement development and subsequent intervention strategies. With these measurement issues resolved, we developed and implemented the intervention described in subsequent papers.

Conclusion

Consistent with our overall CBPR approach to community intervention, we engaged in a collaborative community-university partnership process when developing the measurement model and its accompanying instruments. This paper has outlined our encounter with the nuances involved in cross-cultural measurement selection, adaptation, and development and has clarified how cultural issues occur throughout all phases of measurement development and adaptation and transcend the more common translation/back translation perspective. For some time now, the literature has possessed sophisticated analytic methodologies capable of assessing measurement equivalence across cultural groups at multiple levels and with increasing precision (Van de Vijver and Leung 2000; Van de Vijver and Tanzer 2004; Knight 2000). However, what has been missing in the literature is careful description of respectful methods of local inquiry that allow us to understand constructs and their measurement from a sufficiently deep level of cultural understanding to respond to the shortcomings identified in these analyses. Commensurate with the report of Vinokurov et al. (2007), these methods involve an inquiry into the local community histories and cultural ecology of those groups involved. Our work here suggests it involved negotiation across two worldviews, one from the cultures of science, and another from the cultures of communities.

To be sure, issues raised in prior research on cultural issues in measurement development are found throughout the present study. These include construct equivalence, contextual relevance of item content, item wording, linguistic equivalence, and the response format for responding to questions (Christopher et al. 2005; Stevens et al. 1999). We found it culturally unacceptable to assess certain constructs such as trauma, just as Smith et al. (2004) were not able to assess women’s personal sexual behavior as a risk factor for cervical cancer. We found that the issue of taboo topics of discussion arose with respect to suicide as in prior studies (Solomon and Gottlieb 1999), and that the acculturation level of adolescents was a potential factor in the acceptability of certain ways of asking questions (Legaspi and Orr 2007). Thus, the present measurement development process reflects many issues raised in prior reports of community intervention in American Indian/Alaska Native communities.

But the present account reaches much further into the cultural context through discussions with local community members not only of the translatability of the constructs represented in the measures but also about the assessment of different constructs themselves that more closely reflected protective factors in the local ecology. Taken as an entire narrative, the story of participatory measurement development paints a complex and rich picture whose multiple facets have not been highlighted in the extant literature. The difference between the culture of communities and the culture of science began, in this instance, with divergent views about the concept of measurement itself. Indeed, it is difficult to envision a clearer divergence than that between the quantification emphasis of Western science and the notion that “I don’t think Yup’ik measure anything.” The very concept of measurement itself affected Indigenous responses to the overall preventive intervention project.

There are three additional insights from this elaborate work on measurement development we wish to stress. The first involves the substantive differences made in the model and measures resulting from the collaborative process. Through discussion with our community co-research partners and the YRCC, we ended up with a brief set of measures and a measurement model that differed considerably from our original outcome assessment model. Some measures were dropped entirely (suicide ideation) or only administered after nondrinking youth were screened out using adaptive testing procedures (alcohol quantity and frequency), and these measures were replaced with two measures of more intermediate variables (Umyuangcaryaraq: “Reflecting”–Reflective Processes about Alcohol Use and Yuuyaraqegtaar: “A Way to Live a Very Good, Beautiful Life”–Reasons for Life). Thus, the collaborative process included not only the more traditional issues of translation but also more fundamental issues of construct meaning, respondent burden, and, indeed, the conceptual model underlying the outcome assessment. In addition, the extensive efforts described above also reaffirmed the collaborative commitment of both community members and university co-researchers to work through cultural issues.

Second, most frequently, collaborative measure development is described in terms of the initial collaborative group doing the work itself. Yet, in this project, groups representing the broader communities involved in the project as well as regional representatives provided input resulting in significant further changes in the measurement process. These changes not only improved the acceptability and cultural validity of the final measures used: the commitment to the collaborative process across multiple levels of indigenous input generated a greater trust in and local support for the work. How often a similar sequence of measurement development may have unfolded, in projects with less broad community efforts, is currently unknown.

The third issue involves the population-community distinction. In this instance, the population refers to the Yup’ik Alaska Natives sharing a long cultural and linguistic history. Community, however, refers to the local expression of this shared cultural history. In the present narrative, while sharing traditions, language, and cultural history, the local history surrounding suicide in the communities where the intervention occurred differentially affected the relevance and acceptability of some of the measures. The position taken by the YRCC to let each community make its own decision on how to deal with suicide epitomized the population-to-community distinction we faced in implementing a multisite prevention program designed to address “at-risk” health protective factors. As one YRCC member put it, “we are all Yupik and can understand each other, but each community is also different and we do some things slightly different.” However, the need for comparable measures in multisite programs once more highlighted the tensions between the culture of science and the culture of communities.

To conclude, we have attempted to share interrelated stories of our experiences related to developing measures to assess a cultural intervention as a prevention program for Alaska Native communities. We hope that telling these stories of our lessons learned highlights how CBPR can improve the measurement development process when working with Indigenous communities. In addition, we hope that these stories provide important insights on how “at-risk” indicators and outcomes that are often applied to cultural groups and populations can vary significantly for local communities within that cultural group or population.

References

Allen, J., Mohatt, G. W., Hazel, K., Rasmus, M., Thomas, L., & Lindley, S. (2006). The tools to understand: Community as co-researcher on culture specific protective factors for Alaska Natives. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 32, 41–59. doi:10.1300/J005v32n0104.

Allen, J., & Walsh, J. R. (2000). A construct-based approach to equivalence: Methodologies for cross-cultural and multicultural personality assessment research. In R. H. Dana (Ed.), Handbook of multicultural/cross-cultural personality assessment (pp. 63–85). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Segall, M. H., & Dasen, P. R. (2002). Cross-cultural psychology: Research and applications (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Birman, D., Trickett, E., & Buchanan, R. (2005). A tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(1–2), 87–101. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-1891-y.

Christopher, S., McCormick, A., Smith, A., & Christopher, J. C. (2005). Development of an interview training manual for a cervical health project on the Apsáalooke reservation. Health Promotion Practice, 6(4), 414–422. doi:10.1177/1524839904268521.

Christopher, S., Watts, V., McCormick, A., & Young, S. (2008). Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1398–1406. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757.

Dana, R. H. (2005). Multicultural assessment: Principles, applications, and examples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dick, R. W., Beals, J., Manson, S. M., & Bechtold, D. (1994). Psychometric properties of the suicidal ideation questionnaire in American Indian adolescents. Unpublished manuscript, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver.

Dohan, D., & Levintova, M. (2007). Barriers beyond words: Cancer, culture, and translation in a community of Russian speakers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(Suppl 2), 300–305. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0325-y.

Fisher, P. A., & Ball, T. J. (2003). Triabl participatory research: Mechanisms of a collaborative model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3-4), 207–216.

Fok, C. C. T., Allen, J, Henry, D., & People Awakening Team (2011). The Brief Family Relationships Scale: An adaptation of the relationship dimension of the Family Environment Scale. Assessment. doi:10.1177/1073191111425856.

Fok, C. C. T., Allen, J., Henry, D., Mohatt, G.V., & People Awakening Team (2011). Multicultural Mastery Scale for youth: Multidimensional assessment of culturally mediated coping strategies. Psychological Assessment. doi:10.1037/a0025505.

Hobfoll, S. E., Jackson, A., Hobfoll, I., Pierce, C. A., & Young, S. (2002). The impact of communal-mastery versus self-mastery on emotional outcomes during stressful conditions: A prospective study of Native American women. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 853–871. doi:10.1023/A:1020209220214.

Jacobson, S. A. (1998). Central Yup’ik and the schools: A handbook for teachers. Alaska Native Language Center. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Kelly, J. G. (1970). Antidotes for arrogance: Training for community psychology. American Psychologist, 25(6), 524–531. doi:10.1037/h0029484.

Knight, G. P. (2000). Measurement issues in ‘assessing the home environments of young adolescents’: A commentary. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10(3), 299–305. doi:10.1207/sjra1003_3.

Legaspi, A., & Orr, E. (2007). Disseminating research on community health and well-being: A collaboration between Alaska Native villages and the academe. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 14(1), 24–42. doi:10.5820/aian.1401.2007.5.

Linehan, M. M., Goodstein, J. L., Nielsen, S. L., & Chiles, J. A. (1983). Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking about killing yourself: The reasons for living inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 276–286. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.51.2.276.

Mohatt, N., Fok, C. C. T., Burket, R., Henry, D., & Allen, J. (2011). The Ellangumaciq Awareness Scale: Assessment of awareness of connectedness as a culturally-based protective factor for Native American youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. doi:10.1037/a0025456.

Mohatt, G. V., Hazel, K. L., Allen, J., Stachelrodt, M., Hensel, C., & Fath, R. (2004a). Unheard Alaska: Culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 263–273. doi:10.1023/B:AJCP.0000027011.12346.70.

Mohatt, G. V., Rasmus, S. M., Thomas, L. Allen, J., Hazel, K., & Hensel, C. (2004). “Tied together like a woven hat:” Protective pathways to Alaska Native sobriety, Harm Reduction, 1. Retrieved from http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/1/1/10. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-1-10.

Mohatt, G. V., Rasmus, S. M., Thomas, L., Allen, J., Hazel, K., Marlatt, G. A., et al. (2007). Risk, resilience, and natural recovery: A model of recovery from alcohol abuse for Alaska Natives. Addiction, 103, 205–215. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02057.x.

Moos, R. H., & Moos, B. S. (1994). Family Environment Scale manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists.

Novins, D. K., Beals, J., Roberts, R. E., & Manson, S. M. (1999). Factors associated with suicidal ideation among American Indian adolescents: Does culture matter? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 332–346. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1999.tb00528.x.

Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E. G., Lieberman, M. A., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356. doi:10.2307/2136676.

Pinto, R. M., McKay, M. M., & Escobar, C. (2008). “You’ve gotta know the community”: Minority women make recommendations about community-focused health research. Women and Health, 47, 83–104. doi:10.1300/J013v47n01_05.

Reynolds, W. (1988). Suicidal ideation questionnaire: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Smith, A., Christopher, S., & McCormick, A. K. (2004). Development and implementation of a culturally sensitive cervical health survey: A community-based participatory approach. Women and Health, 40(2), 67–86. doi:10.1300/J013v40n02_05.

Solomon, T. G., & Gottlieb, N. H. (1999). Measures of American Indian traditionality and its relationship to cervical cancer screening. Health Care for Women International, 20, 493–504. doi:10.1080/073993399245584.

Stevens, J., Cornell, C. E., Story, M., French, S. A., Levin, S., Becenti, A., et al. (1999). Development of a questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in American Indian children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(4), 773S–781S.

Suskie, L. A. (1996). Questionnaire survey research: What works (2nd ed.). Tallahassee, FL: Association for Institutional Research.

Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Leung, K. (2000). Methodological issues in psychological research on culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 33–51. doi:10.1177/0022022100031001004.

Van de Vijver, F., & Tanzer, N. K. (2004). Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: An overview. Revue Européenne de psychologie appliquée, 54, 119–135. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2003.12.004.

Vinokurov, A., Geller, D., & Martin, T. (2007). Translation as an ecological tool for instrument development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 6(2), 40–58.

Viswanathan, M., Ammerman, A., Eng, E., Gartlehner, G., Lohr, K. N., Griffith, D., et al. (2004, July). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 99 (Prepared by RTI–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0016). AHRQ Publication 04-E022-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Weaver, H. (1997). The challenges of research in Native American communities: Incorporating principles of cultural competence. Journal of Social Service Research, 23(2), 1–15. doi:10.1300/J079v23n02_01.

Weisberg, H. F., Krosnick, J. A., & Bowen, B. D. (1996). An introduction to survey research, polling, and data analysis (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Willis, G. B. (2005). Cognitive interviewing. A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication.

Wolsko, C., Larden, C., Hopkins, S., & Ruppert, E. (2006). Conceptions of wellness among the Yup’ik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: The vitality of social and natural connection. Ethnicity and Health, 11(4), 345–363. doi:10.1080/13557850600824005.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the youth, families, and the community members for their willingness to work together on this project. Their resilience in the face of adversity speaks to the strength of all Indigenous peoples everywhere. It is their voices and stories that we attempt to honor. Quyana. This research was funded by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the National Center for Research Resources [R21AA016098-01, RO1AA11446; R21AA016098; R24MD001626; P20RR061430].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzalez, J., Trickett, E.J. Collaborative Measurement Development as a Tool in CBPR: Measurement Development and Adaptation within the Cultures of Communities. Am J Community Psychol 54, 112–124 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9655-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9655-1