Abstract

This chapter reviews Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) studies that build suicide prevention capacity among under-resourced and thus vulnerable populations—namely LMIC and Indigenous youth. We first describe this chapter’s aims, define related terms, and address common misconceptions about resource-poor communities. The role of poverty as a contributing and complex correlate to suicide risk is elucidated. We discuss how a variety of research and intervention efforts were used to study culturally idiomatic suicide risk factors and build relevant resource capacity for community members. Because CBPR studies utilize a range of qualitative and quantitative techniques, from focus group thematic analysis to clinical intervention, we provide a detailed review of study designs that promote capacity building strategies among Indigenous and LMIC study samples. We compare several risk identification studies from the LMIC suicide prevention literature to suicide prevention-intervention projects implemented among Indigenous samples. The literature shows that CBPR empowers communities to identify their own barriers to connectedness and create sustainable community engagement activities that prevent suicide. We conclude by highlighting the benefits of capacity building CBPR for resource-poor communities.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Low- and-middle-income-countries (LMIC)

- Indigenous

- Youth suicide

- capacity building

- Community-based participatory research (CBPR)

- Suicide prevention

- Resource-poor

Introduction

Defining Terms and Chapter Focus

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is an increasingly popular research orientation for use among historically oppressed populations. CBPR is a research design where researcher and participant roles are mutually integrative, and both share project decision-making and directioning (Skerrett et al., 2018). True CBPR places equal value on the respective contributions, strengths, and perspectives of both academicians and community members (Israel et al., 1998). The cultural relevance of a CBPR design is to provide results that readily translate into action with immediate and direct benefit to participants (Skerrett et al., 2018; Viswanathan et al., 2004).

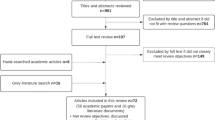

CBPR can be limited to mutually integrative academic and community partnerships but may extend to include clinical-research collaborations that provide an overall benefit to community organizations. Capacity building maximizes CBPR efficacy as it offers members of a community the skills to conduct their own data collection, identify relevant interventions, and implement tools that contribute to building health infrastructure. In practice, capacity building involves a cycle of developing, training, and supporting. It engages community members as partners. Researchers provide feedback mentoring and support for communities that collect information and gather data. The following review includes 41 studies that focus on suicide prevention and capacity building in low-resourced communities through culture-specific approaches, diverse methodologies, community-health empowerment, and research implementation.

To highlight CBPR scholarship and service, this chapter summarizes capacity building efforts that have broadly influenced policy, practice, and/or curriculum changes using study samples that contributed as research partners, consultants, or beneficiaries. For example, a previous CBPR literature review of studies that included youth as partners in the research process found that 26 out of 40 manuscripts had designs where community partnerships were formed with a community-based organization directly related to youth issues or with a specific population of youth, though youth were not contributing partners in the research process (Jacquez et al., 2012). For the purposes of this chapter, we will include community partnership-based suicide research studies such as these to be inclusive of all CBPR research.

This chapter focuses on community-based approaches tailored to build capacity in settings with little mental health infrastructure, undeveloped suicide prevention-intervention protocols, and among populations that remain largely underrepresented (and thus misunderstood) in the scientific literature. Suicide risk in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC’s) and Indigenous contexts are related to historic and systemic oppression, insufficient health surveillance, and/or limited resources. Thus, LMIC and Indigenous youth study samples are prime candidates for suicide prevention through capacity building CBPR.

Forming participatory research designs in predominantly low-income communities and/or communities of color, CBPR bridges the historic gap between researchers and community members (Israel et al., 2010). Capacity building CBPR offers opportunities to develop skill sets in low-income communities and/or communities of color that address concomitant, systemic disparities in mental health infrastructure (Israel et al., 2010). Capacity building suicide prevention uniquely benefits resource-poor communities where isolation and stigma distinctly contribute to suicide risk for individuals who have survived family member and friend suicides, have made a previous attempt, and/or have suicide ideation. We highlight a diverse array of CBPR approaches within the suicide literature that improves understanding, prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of youth affected by suicide in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC’s), under-resourced settings, and historically disadvantaged communities (Indigenous samples).

Related misconceptions about suicide in communities of color are formally presented in other sections of the Handbook (See Chap. 17). Yet, we emphasize two misconceptions that are particularly important to understanding suicide prevention capacity building among LMIC and Indigenous youth samples. First, communities of color are neither monolithic, nor do they present with uniform suicide risk. Collective consciousness and featured community life do not protect LMIC and Indigenous populations from suicide (Durkheim, 1951). In fact, epidemiological observation of suicide risk within a Black youth sample showed heightened risk to suicide ideation for Caribbean Blacks relative to African Americans, but the reverse for suicide attempt risk; elevated suicide attempt risk for African American relative to Caribbean Black individuals (Joe et al., 2009). Therefore, an open mind to the diversity of suicide risk within LMIC and Indigenous samples will prepare the reader for interpretation of this chapter discussion. Second, suicide risk is not explicable by cultural norms and values. Observational data that reports significantly higher suicide deaths among Indigenous youth when compared to non-Indigenous youth does not mean that “being” Indigenous causes suicide (Yuen et al., 1999). This chapter aims to disaggregate the complex behavioral predictors associated with cultural group identification and directs the readers’ focus to intervenable or modifiable targets that prevent death by suicide among youth in LMIC and Indigenous settings.

How Do We Define Persons at Risk for Suicide in Low-Resourced Settings?

We define those most at risk for suicide as those who are least represented in the suicide literature, namely LMIC and Indigenous youth populations. Given that suicide risk peaks along the lifespan in adolescence, we restrict our definition of at-risk study samples to youth in LMIC and Indigenous samples. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth, ages 15–24, and 7.4% of youth in grades 9–12 reported that they had made at least one suicide attempt in the past 12 months (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014; Kann et al., 2018). Although youth are capable of participating in the research process, data from a comprehensive review of 385 studies showed that only a few studies, 56/385 (14.5%), directly partnered with youth in the research process. The majority of research studies (159 out of 385) utilized a research process broadly consistent with community placements, partners, and pairings with adults that target benefits for youth in their age designated organizations (Jacquez et al., 2012). The following studies review research findings that demonstrate underrepresentation and support our emphasis on LMIC and Indigenous youth.

Indigenous people represent one of the world’s most vulnerable suicide demographics. In a systematic review of manuscripts comparing rates of Indigenous suicide to non-Indigenous suicide by country (N = 99), 21 studies showed lower suicide rates among non-Indigenous compared to Indigenous populations (Pollock et al., 2018). While Indigenous suicide rates were consistently elevated relative to non-Indigenous suicide rates, this pattern was not universal across countries (e.g., In Brazil, Indigenous people of Sao Gabriel de Cachoeira, Amazones Rate Ratio (RR) = 9.98 per 100,000, In Taiwan, Atayal RR = 5.69, In America, American Indian and Alaska Native RR = 2.45, In Israel, Bedouin = 0.4 and In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders RR = 0.9; Pollock et al., 2018). The majority of studies examined Indigenous populations (e.g., Alaska native, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and Inuit) in high-income countries (N = 76; United States, Australia, or Canada). LMICs represented n = 22 studies from countries such as Brazil, China/Taiwan, and Fiji. Within LMICs, Palawan communities in the Philippines had the highest suicide rates (134 per 100,000), while Indigenous peoples in Malaysia and some Pacific small island states such as Fiji had rates under 7 per 100,000 population. Further, of studies that provided age-specific rates, youth ages 15–24 had the highest suicide rates of any age group (in 89% of studies, n = 34; Pollock et al., 2018). We consider young, ethnic, and limited resource demographics to be most underrepresented in the suicide literature and those who benefit most from suicide prevention through community capacity building .

What Role Does Poverty Play in Capacity Building Suicide Prevention for Both LMIC and Indigenous Populations?

Poverty takes on many forms in the surveyed resource-poor settings and complexly undergirds a lack of mental health capacity. Without clinical and research mental health capacity, the effects of poverty on suicide outcomes become systematic. For example, risk factors for suicide are linked to the material needs of disadvantaged communities and communal “comorbidities” like epidemic alcohol abuse, inadequate housing, utilities, transportation, and other public services. Such contextual conditions are inextricably interwoven into individuals’ lives and sometimes hopeless realities. Below we explore the multifaceted associations of poverty on suicide outcomes among LMIC and Indigenous youth.

A systematic review of 37 studies classified individual or national level poverty indicators correlated with suicide deaths in LMICs like Ghana, Uganda, Iran, Turkey, and Brazil. Individual poverty was measured by absolute and relative poverty, economic status and wealth assets, unemployment, debt, and/or financial problems. National poverty was coded as an economic crisis, low national income, and/or national inequalities. In adjusted and unadjusted analyses, there was an observed significant positive correlation between poverty and suicides. In the review, LMICs identified as having increased national (n = 9 studies) and individual-level poverty (n = 5 studies) had more suicides (Iemmi et al., 2016).

Baseline data was gathered from three village clusters of the Millennium Villages Project (MVP), which was an integrated, community-led, rural-development program that included Ruhiira, Uganda, Pampaida, Nigeria, and Bonsaaso, Ghana to determine poverty-related risk factors to suicide. In Nigeria, the only risk factor for suicidal ideation (SI) was food insecurity (β = −0.255, p < 0.05; Sweetland et al., 2019). In Ghana (SI = 9.7%) and Uganda (SI = 21.3%), the authors note that endorsed suicidal thoughts were higher than the 3.2% lifetime prevalence in the World Mental Health Survey (Sweetland et al., 2019). MVP sites were purposively selected for an integrated rural-development program to represent distinct agro-agricultural zones and as settings of extreme poverty (defined as having a minimum of 20% of children malnourished).

Qualitative results from an examination of 457 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members from 11 different community sites identified five poverty-related suicide risk factors using triangulation to determine themes from community member responses: lack of education, employment, housing, transport, and services (Dudgeon et al., 2017). Relatedly, a community-based cluster randomized controlled trial evaluated the association between education level and suicide attempts in rural Sri Lanka. Many occupations had a reduced risk of attempted suicide compared to farmers. Government workers, security forces, businessmen, and students had the lowest suicide risk (OR ≤ 0.25). The strongest observed association was a fourfold increased risk of attempted suicide for individuals not having attended school (Knipe et al., 2019a).

Limited access to care is an additional poverty factor that further compounds suicide risk for Indigenous communities. Nasir et al. (2017) performed qualitative interview “consultations” with 63 individuals from 34 service providers or community organizations among Indigenous communities in Queensland, Australia. Over an 18-month period, these 1:1 interviews and large focus group discussions probed with the following questions: “Do you think that the current intervention methods used by caregivers are suitable for Indigenous people of your community?” “What would be a better way to intervene or look after someone who has attempted suicide?” The main themes from respondents identified a need for service providers, access to care, and post-suicide attempt care. Respondents explained that returning to economically impoverished areas without activity and engagement was a clear impediment to the prevention of second attempts. Improved access to post-attempt care was a related aim .

Inadequate access to care is also a salient problem in LMIC contexts. A multiyear ethnographic and epidemiological study was conducted in Haiti to contrast lay versus clinician perceptions of suicide and help-seeking behaviors. Lay community members (n = 16) provided insight into cultural meanings and community norms related to suicide (e.g., formal and informal leaders, support providers, and religious leaders). Lay health educators (n = 3) were a group of community members employed part-time by an NGO to promote health messages regarding handwashing and de-stigmatization of HIV/AIDS to residents in the island’s interior. Focus groups were conducted using semi-structured interviews that elicited participants’ perceptions of the frequency of suicidal behavior, suicide causation, and potential courses of action to alleviate suicidal behavior within the community (Bernard, 2011). The authors compared themes between community members and healthcare workers, identifying quotations to demonstrate both typical and atypical examples of the theme. Data validation was conducted by having team members scrutinize themes, group descriptions, and exemplars, as well as by verifying analyses with Haitian research assistants and a Haitian physician. The results suggested discrepant perceptions of suicide as a problem between healthcare workers and community members. Community members perceived suicide ideation and completion to be a common and serious issue, whereas health care workers did not. Those in need of suicide prevention-intervention are left without resources as healthcare workers and providers were disengaged from their health needs. These data highlight barriers to accessing care for impoverished people and the need for community-led suicide prevention solutions (Hagaman et al., 2013).

The reviewed studies show that multiple poverty indicators contribute as barriers to mental health intervention, individual agency development, and clinical-research infrastructure. Poverty presents as both a direct and indirect risk for suicide. Thus, suicide prevention through capacity building CBPR approaches are particularly efficacious in addressing material needs, available emotional resources , and mental health infrastructures that prevent suicide risk.

What Suicide Risks Are Better Understood with a Cultural-Specific CBPR Approach?

Culture was identified as both a risk (Else et al., 2007) and protective (Mohatt et al., 2014) factor for suicide in the reviewed literature. Results showed that higher scores on the Hawaiian cultural scale (e.g., measures lifestyles, customs/beliefs, activities, folklore/legends, and language) were associated with more youth suicide attempts (Else et al., 2007). Yet, in Alaska, strengthening cultural ties was incorporated into an alcohol use intervention to prevent suicide (Mohatt et al., 2014). For seven non-Hawaiian males who attempted suicide, increased Hawaiian acculturation language and lifestyle scores were significantly associated with suicide attempts (Else et al., 2007). One could suggest from this data that Indigenous Hawaiian culture rather than ethnicity predicts suicide. However, a lower number of suicide attempts were observed among youth with high family cohesion, parent bonding, family support, and organization in this same sample (Else et al., 2007). Relatedly, enculturation, or cultural enrichment, is an efficacious suicide intervention technique shown to reduce risk among Indigenous youth in Canada (Mohatt et al., 2014). Thus, it appears that suicide risk and prevention are culturally specific. Again, suicide risk is not uniform within a cultural community. Scientific research must therefore take into account the cultural gradient to derive accurate and applicable results (Macneil, 2008). For example, a literature review of 27 papers analyzing the effectiveness of CBPR approaches among Native populations showed that the role of local culture is integral and varies (via mechanisms of language, visual materials, local cultural activities, etc.) across interventions (Allen et al., 2014). Rather than relying on standard Westernized elements of an intervention, virtually all described suicide-prevention projects included some community involvement and local input into the intervention (Allen et al., 2014). Capacity building CBPR achieves this aim by culturally forming the research design, intervening on modifiable behaviors and systems, to produce culturally relevant study results.

Cultural adaptation of Western suicide assessment tools facilitates a contextual understanding of suicide risk and knowledge variables not otherwise available, setting the stage for culturally informed suicide prevention-intervention. In a study of 50 youth from Guyana, a DSM-5 (APA, 2013) clinical interview was culturally adapted to ensure item meanings and communication were congruent with native language expressions (Denton, 2021). For example, when assessing clinical symptoms of anxiety, the terms “anxious” and “frustrated” were replaced with “nervous” and “vexed.” Clinical symptoms of anxiety (or nervousness) emerged as having relatively the largest clinical effect difference (than other clinical symptoms: depression, inattention, etc.) between youth with a previous suicide attempt versus those without (Denton, 2021). In a combined South African and Guyanese sample of LMIC youth, somatization (bodily complaints) emerged as a significant risk factor associated with youth endorsement of suicidal ideation (OR = 1.65, p < 0.045; Thornton et al., 2018). One hundred and seventy-five youth, aged 11–18, from South Africa, and 15 youth, aged 12–21, from Guyana, were administered clinical questionnaires at an NGO community–research partnership site. The results showed that after controlling for demographic factors, somatization is a risk factor that informs how indirect communication methods can be preferably reported, which professionals would have to culturally interpret during suicide risk evaluations.

The perceived social environment is another suicide risk assessment variable with culturally specific interpretation. Qualitative interview results from a study conducted in LMIC Guyana showed that community members viewed their society as being made up of small, close-knit villages, where close ties, though in some ways protective against suicide, could also lead to a fear of gossip and limited privacy. The authors linked participants’ description of a highly regulated social environment and fear of failure in this environment with an increased risk for adolescent suicide. An understanding of suicide risk assessment and relevant interpretation of findings such as these are critical to the development of culturally informed suicide prevention efforts (Arora et al., 2020). Because suicide risk in non-Western contexts may differ from suicide risk in traditional, Western-oriented, psychological literature, scientific methods to accurately assess and interpret findings are integral. Capacity building CBPR’s mutually integrative research design and community building techniques solicit participant feedback and relevant understanding of risk factors otherwise overlooked or misunderstood by those external to the study sample .

What CBPR Research Methods Have Been Used to Build Capacity in Resource-Poor and LMIC Settings?

The majority of CBPR studies among LMIC and Indigenous populations utilize a range of qualitative techniques with a core methodological component that involves focus group recruitment and thematic analysis. The 11 research study methodologies presented below demonstrate capacity building efforts that (1) use cultural adaptations to involve stakeholders in the review of research protocols; (2) facilitate group and individual discussion; and (3) learn the idiomatic language of suicide prevention specific to that culture. In resource-poor and LMIC settings, researchers have taught scientific methods and trained community members in coding, analysis, and writing, which are empowering skill sets in under-resourced settings. The research cultural adaptations described below allow participants to identify local supports protective against suicide and represent how CBPR helps to establish a research infrastructure using record review and surveillance system registry.

US research team members collaborated with secondary school principals in Guyana to conduct focus groups and assess views on: (a) suicide as a problem in their community and (b) risk factors for suicidality. School stakeholders and Guyanese community members reviewed the protocol and provided feedback regarding clarity of content and language. Three focus groups were developed that ranged in size from five to eight adult stakeholders and ranged in length from 41 to 55 min. Reoccurring themes summarized academic pressure on students, parents’ expectations of students, romantic relationships, cultural expectations, and religious pressure as risk factors for suicide among Guyanese youth. Parents’ negative reactions and adults’ invalidating responses to youths’ disclosure of suicide were endorsed as risk factors for suicide among Guyanese adolescents (Arora et al., 2020).

Photovoice (PV) and Digital Storytelling (DST) are qualitative CBPR techniques used to understand suicide prevention needs among tribal community members. In one study, photovoice assessments were conducted, with youth receiving disposable cameras from researchers, who directed them to select three photos that represented suicide-related strengths and challenges in their community (Holliday et al., 2018). In the case of DST, youth took and organized 20 photos taken around their community, which they then narrated with a 3-min statement. PV and DST represent augmented focus groups in which participants combine digital media and storytelling to prompt group-based discussions on what is needed in the community for suicide prevention. In this study, PV and DST methods/techniques both identified substance-use management as a viable means for suicide prevention. The PV groups identified the following challenges: (1) neglecting the environment; (2) accessing community services for mental health and substance abuse; and (3) scarce health and wellness activities for youth. DST results demonstrated that both personal struggles and understanding the substance-use and suicide of friends and family were areas of concern. Tribal partners found that culturally adapted research tools, such as PV and DST, were analogous to oral forms of traditional, indigenous storytelling that synthesize various kinds of information to both formalize a community’s history and educate its members (Holliday et al., 2018).

Jacquez et al.’s, 2012 review of youth CBPR involvement explicitly details ways to build research capacity using youth samples. The research process was categorized into five phases: Phase 1 (54% of reviewed studies): youth active input in research through a Youth Advisory Board or other formal council mechanism. Phase 2 (77% of reviewed studies): youth involved in identifying priorities, goals, and research questions through a needs assessment. Phase 3 (84%): youth involved in research design and conduct. Phase 4 (54% of reviewed studies): youth participated in data analysis, summarizing data, and/or interpreting and understanding research findings. Phase 5 (52% of reviewed studies): youth participated in disseminating and translating research findings. Although these data show that only a few studies (56 out of 385) directly partnered with youth in the research process, it provides a reference for multiple ways to include youth in the research process (Jacquez et al., 2012).

Qualitative data collection and thematic analyses were used to understand the benefits and risks of disclosing past suicidal activity among adults aged 20–63 in a resource-poor urban population in Chicago, US. Researchers coded 12 semi-structured group interviews and 24 follow-up individual interviews to identify words or phrases that represented benefits or risks consequential to suicide disclosure. A total of eight meetings were held; nine self-benefits and eight self-risks were identified. Perceived benefits to self after suicide activity disclosure were: (1) expanded social support; (2) finding peers who understand; (3) strengthened relationships; (4) enhanced coping strategies; (5) personal recovery achievement; (6) gained perspective and self-reflection; (7) end to the secrecy; (8) access to professional treatment; and (9) maintained personal safety. Perceived risks to self were: (1) stigmatization; (2) overreaction; (3) receipt of unwanted treatment; (4) unsupportive reactions; (5) lack of understanding from others; (6) emotionally difficult (task) to do; (7) breach of privacy; and (8) the futility of disclosure. Youth analysis and identification of risks and benefits to suicide disclosure served as validating and therapeutic data collection techniques (Sheehan et al., 2019).

The effectiveness , acceptability, and feasibility of a culturally informed QPR (Question, Persuade, and Refer) suicide prevention gatekeeper training program was examined in LMIC, Guyana. QPR builds capacity by educating any community member on how to identify suicide warning signs, inquire about suicide risk, provide hope for the at-risk person, and get help for the person identified to be at-risk (Quinnett, 2011). In this pilot study, community stakeholders such as teachers (n = 12), administrators (n = 3), and other school staff (n = 1) were placed into groups of 5–8 and taught how to recognize the signs of suicide, deliver mental health interventions, and refer at-risk youth to a mental health worker (Quinnett, 2011). One research team member, who received certification from the QPR Institute prior to conducting research in Guyana, acted as the instructor of the suicide prevention trainings, while the other researchers completed treatment adherence checklists and assisted participants as the trainings were in session. This culturally informed capacity building CBPR resulted in a significant increase in participants’ knowledge of suicide prevention from pretest to posttest as well as significant decreases in rigid and judgmental attitudes toward suicide (Persaud et al., 2019).

A community partnership CBPR project sought to identify limitations of existing suicide prevention programs, improve referral rates, perceptions of mental health care, and technological outreach among low SES urban youth. Community partners met bimonthly with researchers, from July 2010 to June 2011, and researchers trained community partners to qualitatively code and analyze focus group data from nine Latino youth. Youth responses indicated a need for more culturally relevant interventions and that parents needed to show a willingness to participate in activities outside the community. They suggested that interventions be delivered by people with whom community members could identify in an effort to increase acceptance of educational campaigns, family involvement, and new, intervention-associated technology (Ford-Paz et al., 2013).

A qualitative study built community capacity by training community members, or coresearchers, to perform youth suicide risk identification . Twenty-two coresearchers participated in a 5-day workshop. Workshop interview training focused on basic project management, participatory action research processes, culturally safe and responsive research methods, research ethics, qualitative data collection, thematic analysis, and critical reflection on practice and processes. Coresearchers had regular communication with research partners, who supplied them with writing assistance and data analytic training. As a result, coresearchers reported feelings of empowerment from having received interview training and from having developed their writing skills. They received ongoing support from researchers at the university, with whom they had regular communication with data analysis assistance, help compiling site reports, and social and emotional well-being workshops. These coresearchers disseminated 40 hardcopy reports that summarized community methods for suicide risk assessment. In a 2-year follow-up interview, coresearchers expressed a heightened sense of community ownership, feelings of empowerment and personal efficacy, commitment, and growth. Such feedback demonstrates that mutual support and communication between university- and community-affiliated researchers can yield a wealth of tacit, positive community, and individual-level effects that also inherently protect against suicide (Dudgeon et al., 2017).

The collaborative development of an epidemiological surveillance system for White Mountain Apache populations represents another example of a suicide prevention program wedded to capacity building. Roughly 15,500 White Mountain Apache community members were examined for suicide risk. Apache case managers were hired and trained to educate community members in a suicide surveillance system by learning to administer data registry forms completed by police, fire, medical, school, social service personnel, religious leaders, among other community members exposed to a suicide. Apache case managers validated and entered data from forms, followed up on registry cases, facilitated referrals, liaised with community leaders and providers to interpret data, and developed ideas for suicide prevention strategies . Paraprofessionals were also hired and trained to formalize the mandated reporting process, digitize the registry system, analyze quarterly trends, and engage community leaders in interpreting surveillance data to inform prevention strategies. Forty-one individuals died by suicide between 2001 and 2006, the period of development for the surveillance system. Twenty-five of the 41 suicides (61%) were among people younger than 25 years, with a mean age of 19.4 years (SD = 3.6 years; median = 19.8 years). The majority of suicides were reported to the surveillance system via the tribal police department or social services department. The surveillance system is the first to quantify the burden of suicide morbidity in rural populations with barriers to clinical care among youth (Mullany et al., 2009).

In a descriptive, ethnographic study , 30 Pacific Northwest American Indian youth, aged 14–19, who were participating in an ongoing suicide risk assessment/intervention, were separated into three focus groups to answer questions about stressors, family and community strengths support, and future hopes. The youth responded that “getting into trouble,” racism , family-related stress, gossip, and group pressure were major stressors. The ethnographic design identified The Boys and Girls Club, intertribal events, community Pow Wow, tutoring programs, trips to the city, and family to be supportive. Hopes included: the return of tradition, tribal unity, better living conditions, better roads, sober recreation, and economic stability in the future (Strickland & Cooper, 2011).

Record review is an easily overlooked suicide prevention method that can build capacity. In Guam, record review was used to identify contributing risk factors to completed suicide cases. Researchers partnered with native and foreign residents from Guam and trained residents to survey and analyze published death registration data, taken predominantly from the Guam Department of Public Health and Social Services. The trained residents classified 635 suicides from 1974 to 2006, using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes that detail deaths due to “suicide and self-inflicted injury” from 1999, “intentional self-harm,” and sequelae grouped in the available data (Booth, 2010). The data showed an increase in suicide incidence through the 1990s. Community interpretation of these data linked the increased suicide incidence to the formation of suicide pacts by Guamanian preteens and teens through the 1990s. By early 2001, Guamanian police had compiled a list of 50 members, all teenagers, who belonged, via Internet chatrooms, to a group called the “Prestigious Angels.” Twenty-two of the 50 members compiled in the list had died by suicide. The skills gained in conducting a record review proved to be a significant data analytic and collaborative tool for community suicide prevention (Booth, 2010). The methodologies surveyed demonstrate the range and diversity of research methods that build clinical-research capacity and are indeed CBPR. These include focus groups, suicide prevention gatekeeper training programs, community partnerships, community risk assessment, implementation of epidemiological surveillance, descriptive ethnographic studies , and record review.

How Do CBPR Suicide Prevention Studies, to Date, Compare Between LMIC Samples and Indigenous Samples?

While LMICs and Indigenous communities may share a common socioeconomic risk profile for suicide, the bodies of research corresponding to suicide prevention-intervention in these two broad demographic categories have advanced to different stages along the research continuum. LMIC suicide prevention research has focused on the identification of risk and protective factors, mental health capacity assessments, and means prevention. In contrast, suicide prevention research among Indigenous samples has advanced to intervention projects and even some translational science models. Since psychosocial risk assessments and identifications of suicide risk and protective factor studies have been conducted in both LMIC and Indigenous samples, using a variety of culturally adapted, methodological designs, we will first present LMIC suicide prevention studies for comparative purposes.

Programme for Improving Mental Health Care PRIME intervention was implemented to generate reliable data from primary care settings on suicide risk in five LMIC countries (Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda). The findings showed that one out of ten persons presenting at primary care facilities in the five LMIC sites reported suicidal ideation and one out of 45 attempted suicide within the past year. Among those with plans, at least 24% attempted suicide across all samples, reaching over 50% in Nepal, South Africa, and Ethiopia. Specifically, nearly 40% of people with a suicide plan attempted suicide in India and more than 70% in Nepal and Ethiopia. These data point toward important opportunities to engage in suicide risk reduction, especially in LMIC primary care settings (Jordans et al., 2018).

In a cross-sectional design and purposive sampling of high suicide risk youth in Guyana, this community partnership recruited 25 youth, ages 6–21, to identify risk and protective correlates for lifetime suicide attempt. Using well-established, quantitative, clinical-research assessment tools, the researchers evaluated the role of multiple clinical correlates for youth suicidal behavior. Correlates were: atypicality, locus of control, social stress, anxiety, sense of inadequacy, attention problems, hyperactivity, sensation seeking, somatization, sleep problems, inattention, depression, anger and irritability, relations with parents, interpersonal relations, self-esteem, and self-reliance. In this small LMIC sample, the only significant distinction between youth who had no attempt history (n = 16) and youth with an attempt history (n = 9) was self-reported lack of interpersonal relationship skills on a subscale of the Behavioral Assessment Schedule for Children (BASC-A and BASC-C) (p = 0.02; Denton et al., 2017).

Researchers assessed resource availability and the role of health systems in the prevention of suicide in Gilgit-Baltistan, (northern) Pakistan. They evaluated the perceptions of 12 stakeholders (e.g., teachers, healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, midwives), police officers, media personnel, District Health Officer (DHO), religious leaders (Masjid Imam-Sunni and Mukhi-Ismaili community), youth, local community members (parents) and NGOs. Eighteen questions were asked that explored the perception of suicide as a health issue, the role of the health system, and the challenges to suicide prevention in the health system. Study results showed that the unavailability of mental health professionals is one of the biggest challenges for the health system. People had to travel long distances to another city to receive mental healthcare. The majority of persons that died by suicide were in contact with health services in the weeks before the suicide. Resource organizations worked in isolation and lacked coordination. The following recommendations were made to address health system gaps in suicide prevention resources, according to key community informants: create awareness about mental health in the community through electronic and print media as well as community awareness sessions. In addition, they identified the need to introduce school mental health programs for early identification of risk factors among adolescents and provide facilities for youth that could help strengthen resilience and coping power (Anjum et al., 2020).

Suicide means prevention or limiting access to lethal methods used for suicide is a well-documented and effective way to save lives. Using data available from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, researchers assessed the efficacy of suicide means prevention pesticide ban in Sri Lanka between 2011 and 2015 when dimethoate and fenthion were fully banned and 2 years into a 3-year paraquat ban. The demonstrated community partnership between researchers, Sri Lanka Department of Police, and the Division of Statistics used suicide data search terms, like “poisoning” and “other method” categories to represent pesticide poisoning suicide deaths for the years of examination. The results showed that the age-standardized overall suicide rate dropped by 21% from 18.3 to 14.3 per 100,000. Pesticides accounted for 38% of suicides deaths in 2000 (start of pre-ban period) but dropped to 30% in 2015 (Knipe et al., 2017).

Researchers sought permission from the University of Peradeniya (Peradeniya, Sri Lanka) and Rajarata University of Sri Lanka (Mihintale, Sri Lanka) to foster multilevel engagement and community partnership for studying the aftercare of self-harm patients presenting to the hospital. First, the chief village official was approached to seek consent for community enrollments. Then, verbal consent was sought at the start of each household survey. Data were collected from 11 small and two larger peripheral hospitals, with sicker patients. For a median of 1.9 years, 2259 individuals with index hospital presentation for nonfatal self-harm were followed up. The results showed that 127 (111 nonfatal and 16 fatal) repeat self-harm episodes were reported in 116 individuals. Using survival models, the estimated risk for repeat self-harm within 12 months was 3.1%. In the largest prospective study from an LMIC in south Asia to estimate the risk of repeat self-harm by any method, the findings support that there is a relatively low rate of repeat self-harm and subsequent suicide death in LMICs relative to high-income countries (HICs) (Knipe et al., 2019b).

The five previously summarized studies were all conducted in LMIC settings and offered suicide prevention through capacity building, by assessing risk and identification, means prevention, community–research partnerships, and defining mental health infrastructure targets for training and intervention (Anjum et al., 2020; Denton et al., 2017; Jordans et al., 2018; Knipe et al., 2017; Knipe et al., 2019b). Similar suicide prevention methodologies have been implemented among Indigenous samples in addition to the more direct testing of suicide prevention-interventions. The following seven studies summarize capacity building suicide prevention-interventions among Indigenous samples (Allen et al., 2009; Allen et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2018; Clifford et al., 2013; Cwik et al., 2019; Langdon et al., 2016; Rasmus, 2014).

An enculturation suicide prevention-intervention program , consisting of 36 modules, was designed for Yup’ik Alaskan youth, ages 12–17. It focused on teaching 2–5 traditional Yup’ik cultural practices (e.g., problem-solving, communal mastery, and safety) as suicide protective factors. An example of a particular module was called Watch the Ice. Youth would travel onto river ice with their families and were taught by Elders to monitor conditions for safety. Outcomes of the intervention were evaluated for three different levels of protective factors: individual, family, and community. Measurable and intermediate effects were demonstrated at each proposed level, with significant effects observed on the individual and familial level (Individual: d = 0.46, p = 0.01; Family: d = 0.38, p = 0.03; Community: d = 0.45, p = 0.06). The intervention resulted in multilevel suicide prevention efforts, including more individual self-efficacy and communal mastery—a concept opposed to (Western) self-mastery, that involves joining with others to tap resources embedded within close, interwoven social networks (Hobfoll et al., 2002). Youth wanted to be role models, wanted to receive more familial affection/praise, and wanted adult members of the community to model sobriety. In the community, there was increased advocacy for police protection. Spontaneous repetition of the Prayer Walk module occurred across the community, whereby various members of the community, of all faiths, walked along a self-determined route and offered prayers for critical suicide prevention resources (e.g., clinic, school, churches, Tribal office, etc.; Allen et al., 2014).

Longitudinal outcomes of the aforementioned enculturation suicide prevention-intervention were evaluated 12 months after intervention completion. Implementation of the intervention was evaluated based on a comparison between treatment (n = 61 participants) and control communities (n = 77 participants). The treatment community used a codeveloped (with Yup’ik stakeholders and adapted by Elders) cultural suicide prevention-intervention, while the control community implemented the same suicide prevention program developed outside the community. The treatment community with the codeveloped intervention had more youth attend suicide prevention modules 6.78 (vs. 2.31) relative to control and reported higher reason for living scores. The Yuuyaraqegtaar Reasons for Life scale is a cultural adaptation of Linehan et al.’s (1983) Reasons for Living Inventory that assesses strengths that tap into the meaning of life, culture-specific beliefs, and experiences that make life enjoyable and worthwhile. Among the treatment community youth, reasons for living scale scores had an average +12.3 increase 12 months after the intervention. These findings demonstrate examinations of sustainable suicide prevention-intervention among Indigenous youth in the context of a culturally tailored suicide prevention-intervention (Allen et al., 2018).

Two-years post-suicide intervention qualitative interviews about community-level outcomes/changes were conducted among Yup’ik community members to explore their experiences. Nine follow-up interviews, one focus group (n = 15) for the local Community Planning Group (CPG —primary oversight group for the project), and one focus group (n = 6) for the local work group that developed and delivered the intervention, were asked an initial question: “Please tell me about your involvement with the Elluam Tungiinun (Towards Wellness) project.” Participant responses were audio-recorded and transcribed to identify recurring themes. In rank order, community members reported that, on a community level, there was an: (1) increase in communication, (2) increase in sharing of knowledge and feelings, (3) utilization of traditional Yup’ik ways in research activities and meetings, (4) persistence of the project, (5) community ownership of the project, and (6) increase in intergenerational interaction (Rasmus, 2014).

An alcohol abuse intervention was used among 54 Yup’ik indigenous youth to build 13 suicide protective factors. The efficacy of the intervention aimed to develop health knowledge and leadership as a community resource over a 12-month study period. Twenty-six prevention activities were delivered in 32 sessions, to 54 youth, by one school leader, three tribal and city leaders, and one Elder (n = 5). Using the 21-item Community Readiness Assessment (CRA), knowledge, leadership, and community efforts scale, there was an observed 2 point increase (from 3.5 to 5.6) indicating improved use of community suicide protective factors among youth (Allen et al., 2009).

A feasibility and pilot examination of CBPR approaches was conducted among White Apache American Indians (AI). Cwik et al. (2019) developed a community connectedness suicide prevention-intervention for White Apache American Indians that would build training capacity and suicide prevention knowledge for youth enrolled in school. The educational intervention addressed topics of culture, including respect, Apache culture, spirituality and ways of life, self-esteem and self-worth, endurance, gender roles, Apache history, the importance of education, health and fitness, relationships and the Clan System, discipline, and communication. Over a 4.5 year period, the researchers interviewed Elders, met with Elder councils, and developed a curriculum that would be implemented by Elders in 10 schools with youth samples ranging from 35 to 637 persons in each school. Overall more than 1000 AI youth were given the suicide prevention curriculum as taught by a group of 8–10 Elders. Intergenerational ties were formed, which were interpreted to have a “calming effect” on the youth. The youth showed more respect for one another. Most importantly, the entire research intervention development and implementation were driven by the Elders (there was no predetermined structure or content) (Cwik et al., 2019).

A longitudinal CBPR study aimed to determine the outcomes of a 6-month structured suicide intervention curriculum that facilitated enculturation: drumming, dancing, singing, and beadwork on youth suicide ideation endorsements and protective factors. The study was conducted among Lumbee youth, ages 11–18 (n = 22), and their mental health professionals (n = 16) in Robeson County, North Carolina. Youth were asked to rate their enjoyment and willingness to continue in the program on a scale of 1 (not likely) to 10 (very likely). The youth’s average rating score was 9.1. Youth reported less suicidal ideation and more protective factors on pre- and post-intervention assessments, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Langdon et al., 2016).

In a systematic review of 38 articles used to evaluate the effectiveness of suicide interventions among Indigenous samples, a total of nine intervention studies were identified. Seven of the nine studies included youth samples with an average age of 20 years old. Four studies used community prevention-interventions, three used gatekeeper trainings, and two used education training programs. Each of the studies demonstrated some efficacy. Seven out of nine studies showed a statistically significant improvement in at least one outcome metric, such as (1) a culturally tailored school-based life skills curriculum reducing hopelessness and suicide vulnerability, (2) an Alaskan alcohol restriction community prevention reducing suicide for persons with low level restrictions, (3) a community prevention among American Indian youth that showed significant reductions in rates of suicidal gestures and attempts, (4) a gatekeeper training among Aboriginal Australian community members with significant pre-post training and increases in knowledge, intentions, and confidence, (5) a gatekeeper workshop among Aboriginal youth that showed significant improvements in knowledge and confidence in how to identify individuals at risk for suicide, (6) gatekeeper training, education workshops, social activities, individual counseling, and education seminars among American Indian college students with reported improvements in problem-solving ability, and (7) a community prevention module among Alaskan Indigenous youth with significant increase in number of protective behaviors (Clifford et al., 2013).

LMIC settings provide relatively more etiological results and targets for suicide means prevention when compared to longitudinal suicide intervention studies conducted among Indigenous samples. The literature on suicide prevention for both samples remains scant, in part because methodologically rigorous research studies that build research capacity and engage Indigenous partners equitably are likely to be expensive, requiring significant funding (Clifford et al., 2013).

How Are LMIC and Indigenous Communities Empowered Through Capacity Building Suicide Prevention CBPR?

CBPR , taken as a whole, represents an inherently empowering set of research methodologies. Using CBPR, communities are able to identify their own barriers to connectedness and suicide prevention, develop groups, and create projects that address suicide risk. CBPR training workshops provide concrete skills to attendees and foster dissemination of suicide prevention knowledge for family and community members. A CBPR intervention or suicide risk assessment is also an opportunity for an under-resourced community to engage with an institution outside of the community, in partnership, and with an equal stake in research outcomes. CBPR suicide risk and protective factor assessment or intervention builds capacity, prompts community-wide reflection, fosters collaborative science and intergenerational engagement. To this end, we make the argument that the very kinds of community-strengthening ties that protect against suicide are inherent to CBPR and that risk and protective factor assessments may function as tacit interventions in and of themselves. In this way, CBPR’s mechanism of intervention may be analogous to that of one-on-one individual talk therapies, in which patients are given the tools to reflect on their own psychology and derive curative benefit from that reflection. Building research capacity in LMIC and Indigenous population settings may thus serve as suicide prevention-intervention. The following summary of three studies demonstrates the above-described community empowerment using capacity building CBPR.

A purposive sampling design recruited 32 youth (6–16 years old) from a large Midwestern Urban Indian Health Organization (UIHO) to identify barriers to and positive influences on community connectedness. The goal was to build a suicide prevention-intervention through increased youth help-seeking behavior. In addition to a demographic survey (20 questions regarding tribal affiliation, identity, and socioeconomic factors), a survey measuring the participant’s experience with suicide was given. In a focus group format, youth were asked both closed- and open-ended questions, including What do you know about suicide prevention at the Indian center? How many people are aware of the National Suicide Prevention hotline? How much of a concern is AI/AN youth suicide in the community? Responses were evaluated based on a well-established 15-point checklist inducted via thematic analysis. Participants identified that their own barriers to community connectedness and help-seeking were related to (1) the dualistic normalization and stigmatization of suicide; (2) the need for more suicide prevention resources in the form of knowledge and supports; and (3) more intergenerational engagement (Doria et al., 2020).

A 1-week group interview of 36 Inuit youth in Nunavut, Canada, was conducted to develop resilience and leadership skills that would sustainably reduce suicide risk. Youth engaged in guided dialog and developed “meaning maps” that were used to pinpoint and visually illustrate connections between people and environments. “Meaning maps” serve as a tool to visualize assets and social capital. They also generated ideas for collective projects. Over the course of 3 years, youth demonstrated ownership, leadership skills, and worked as co-facilitators for some of the 46 projects compiled. Sustainable projects included: athletic activities and dancing (e.g., swimming pool, hockey rink), social investments (e.g., crafts center, daycare), and business ventures (e.g., hunting store, clothes store) (Anang et al., 2019).

In another study of eight Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities, suicide risk and protective factors were broken down across individual, family, and community levels. Sixteen coresearcher community members were trained to facilitate the implementation of a social and emotional well-being empowerment program, lasting 12 months, to an estimated 40 community members. The coresearchers delivered a 2-day introductory Social and Emotional Well Being workshop training that would support community members to exert more control over personal health, conduct focus groups, and implement suicide consultation feedback. Community members were able to identify social determinants of health at each level of research interest. Individual suicide risks included: Health and/or mental health, employment, drugs and alcohol, family, children and/or young people, violence, personal issues, housing, racism, and/or discrimination. Familial suicide risks included: Drugs, alcohol, gambling, health and/or mental health, family, financial issues, employment, violence, housing, communication breakdown. Community suicide risks included: drugs and alcohol, employment, violence, health and/or mental health, youth, family, accessing services, housing, racism, and/or discrimination. Consistent risks identified across all three levels include drugs/alcohol, violence, mental health, employment, and housing. Resultant expressions of community ownership, empowerment, and personal efficacy of participants were subsequent outcomes of this suicide prevention through capacity building project in low-resourced communities (Cox et al., 2014). CBPR can yield a number of secondary benefits to a community beyond concrete research findings. Research projects can strengthen community ties, facilitate intracommunity connections, and increase participant knowledge and self-efficacy over study period time. The benefits of such community investment are slow but long-lasting .

Conclusion

We provided a scientific overview of suicide prevention using capacity building CBPR approaches in at-risk and understudied LMIC and Indigenous youth samples. We aimed to include a comprehensive array of studies that would demonstrate methodological variety (cross-sectional, longitudinal, qualitative, systematic review, etc.) across diverse populations with high suicide risk youth (Indigenous, LMIC, and resource-poor samples) using a variety of study designs (epidemiological, correlational, intervention, etc.). One unique and telling observation from our review is the utility of teaching community members how to record and review records of death by suicide, which in turn, helped communities to identify youth directly exposed to peers with suicide risk. Demonstrably, reducing youth suicide risk can thus be performed directly by interview or intervention with youth targets, and/or indirectly by engaging community leaders to develop systems that identify at-risk youth. To this end, CBPR is a validating research tool and resource that provides contextualized scientific interpretation for both researcher and community. Our study summaries also show that youth can be engaged in CBPR approaches. While several of the studies expressed direct benefits for involved youth, improvements in community-health education, social networking, and relational resources slowly change health access over time. Therefore, indirect and longer term investments of capacity building CBPR are yet to be evaluated for the indirect benefit to youth and future generations. The formal properties of suicide research and intervention reviewed in the literature are manifold and overlapping, as are the similarities between indigenous and LMIC samples. Suicide prevention through capacity building is an invaluable scientific resource with generalizable solutions.

References

Allen, J., Mohatt, G., Fok, C. C. T., Henry, D., & People Awakening Team. (2009). Suicide prevention as a community development process: Understanding circumpolar youth suicide prevention through community level outcomes. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 68(3), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v68i3.18328

Allen, J., Mohatt, G. V., Beehler, S., & Rowe, H. L. (2014). People awakening: Collaborative research to develop cultural strategies for prevention in community intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9647-1

Allen, J., Rasmus, S. M., Fok, C., Charles, B., Henry, D., & Team, Q. (2018). Multi-level cultural intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol use risk with Alaska native youth: A nonrandomized comparison of treatment intensity. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 19(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0798-9

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Anang, P., Haqpi, E. N. E., Gordon, E., Gottlieb, N., & Bronson, M. (2019). Building on strengths in Naujaat: The process of engaging Inuit youth in suicide prevention. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 78(2), Article 1508321. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2018.1508321

Anjum, A., Ali, T. S., Pradhan, N. A., Khan, M., & Karmaliani, R. (2020). Perceptions of stakeholders about the role of health system in suicide prevention in Ghizer, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. BMC Public Health, 20(1), Article 991. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09081-x

Arora, P. G., Persaud, S., & Parr, K. (2020). Risk and protective factors for suicide among Guyanese youth: Youth and stakeholder perspectives. International Journal of Psychology, 55(4), 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12625

Bernard, H. R. (2011). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (5th ed.). AltaMira Press.

Booth, H. (2010). The evolution of epidemic suicide on Guam: Context and contagion. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 40(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.1

Clifford, A. C., Doran, C. M., & Tsey, K. (2013). A systematic review of suicide prevention interventions targeting indigenous peoples in Australia, United States, Canada and New Zealand. BMC Public Health, 13(1), Article 463. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-463

Cox, A., Dudgeon, P., Holland, C., Kelly, K., Scrine, C., & Walker, R. (2014). Using participatory action research to prevent suicide in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander communities. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 20(4), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY14043

Cwik, M., Goklish, N., Masten, K., Lee, A., Suttle, R., Alchesay, M., O’Keefe, V., & Barlow, A. (2019). “Let our apache heritage and culture live on forever and teach the young ones”: Development of the elders’ resilience curriculum, an upstream suicide prevention approach for American Indian youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12351

Denton, E. (2021). Community-based participatory research: Suicide prevention for youth at highest risk in Guyana. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 51(2), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12693

Denton, E., Musa, G. J., & Hoven, C. (2017). Suicide behavior among Guyanese orphans: Identification of suicide risk and protective factors in a low-middle-income-country. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 29(3), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2017.1372286

Doria, C. M., Momper, S. L., & Burrage, R. L. (2020). “Togetherness:” The role of intergenerational and cultural engagement in urban American Indian and Alaskan Native youth suicide prevention. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 30(1–2), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2020.1770648

Dudgeon, P., Scrine, C., Cox, A., & Walker, R. (2017). Facilitating empowerment and self-determination through participatory action research: Findings from the National Empowerment Project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917699515

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide, a study in sociology (J. A. Spaulding & G. Simpson, Trans.). Routledge. (Original work published 1897).

Else, I. R. N., Andrade, N. N., & Nahulu, L. B. (2007). Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Studies, 31(5), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180701244595

Ford-Paz, R. E., Reinhard, C., Kuebbeler, A., Contreras, R., & Sánchez, B. (2013). Culturally tailored depression/suicide prevention in Latino youth: Community perspectives. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42(4), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9368-5

Hagaman, A. K., Wagenaar, B. H., Mclean, K. E., Kaiser, B. N., Winskell, K., & Kohrt, B. A. (2013). Suicide in rural Haiti: Clinical and community perceptions of prevalence, etiology, and prevention. Social Science and Medicine, 83, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.032

Hobfoll, S. E., Jackson, A., Hobfoll, I., Pierce, C. A., & Young, S. (2002). The impact of communal-mastery versus self-mastery on emotional outcomes during stressful conditions: A prospective study of Native American women. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(6), 853–871. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020209220214

Holliday, C. E., Wynne, M., Katz, J., Ford, C., & Barbosa-Leiker, C. (2018). A CBPR approach to finding community strengths and challenges to prevent youth suicide and substance abuse. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616679234

Iemmi, V., Bantjes, J., Coast, E., Channer, K., Leone, T., McDaid, D., Palfreyman, A., Stephens, B., & Lund, C. (2016). Suicide and poverty in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30066-9

Israel, B. A., Coombe, C. M., Cheezum, R. R., Schulz, A. J., McGranaghan, R. J., Lichtenstein, R., Reyes, A. G., Clement, J., & Burris, A. (2010). Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2094–2102. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

Jacquez, F., Vaughn, L. M., & Wagner, E. (2012). Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: A review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research. American Journal of Psychology, 51(1–2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9533-7

Joe, S., Baser, R. S., Neighbors, H. W., Caldwell, C. H., & Jackson, J. S. (2009). 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among black adolescents in the National Survey of American life. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf

Jordans, M., Rathod, S., Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Kigozi, F., Kohrt, B., Luitel, N., Peterson, I., Shidhaye, R., Ssebunnya, J., Patel, V., & Lund, C. (2018). Suicidal ideation and behavior among community and health care seeking populations in five low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(4), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000038

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Bradford, D., Yamakawa, Y., Leon, M., Brener, N., & Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 67(8), 1–114. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/ss/ss6708a1.htm

Knipe, D. W., Chang, S.-S., Dawson, A., Eddleston, M., Konradsen, F., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2017). Suicide prevention through means restriction: Impact of the 2008-2011 pesticide restrictions on suicide in Sri Lanka. PLoS One, 12(4), Article e0176750. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172893

Knipe, D. W., Gunnell, D., Pieris, R., Priyadarshana, C., Weerasinghe, M., Pearson, M., Jayamanne, S., Hawton, K., Konradsen, F., Eddleston, M., & Metcalfe, C. (2019a). Socioeconomic position and suicidal behavior in rural Sri Lanka: A prospective cohort study of 168,000+ people. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(7), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01672-3

Knipe, D., Metcalfe, C., Hawton, K., Pearson, M., Dawson, A., Jayamanne, S., Konradsen, F., Eddleston, M., & Gunnell, D. (2019b). Risk of suicide and repeat self-harm after hospital attendance for non-fatal self-harm in Sri Lanka: A cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(8), 659–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30214-7

Langdon, S. E., Golden, S. L., Arnold, E. M., Maynor, R. F., Bryant, A., Freeman, V. K., & Bell, R. A. (2016). Lessons learned from a community-based participatory research mental health promotion program for American Indian youth. Health Promotion Practice, 17(3), 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839916636568

Linehan, M. M., Goodstein, J. L., Nielsen, S. L., & Chiles, J. A. (1983). Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking about killing yourself: The reasons for living inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(2), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.51.2.276

MacNeil, M. (2008). An epidemiologic study of aboriginal adolescent risk in Canada: The meaning of suicide. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2008.00117.x

Mohatt, G. V., Fok, C. C. T., Henry, D., People Awakening Team, & Allen, J. (2014). Feasibility of a community intervention for the prevention of suicide and alcohol abuse with Yup’ik Alaska Native Youth: The Elluam Tungiinum and Yupiucimta Asvairtuumallerkaa studies. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9646-2

Mullany, B., Barlow, A., Goklish, N., Larzelere-Hinton, F., Cwik, M., Craig, M., & Walkup, J. T. (2009). Toward understanding suicide among youths: Results from the White Mountain Apache tribal mandated suicide surveillance system, 2001–2006. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1840–1848. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.154880

Nasir, B., Kisely, S., Hides, L., Ranmuthugala, G., Brennan-Olsen, S., Nicholson, G. C., Gill, N. S., Hayman, N., Witherspoon, S., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S., & Toombs, M. (2017, April 26–29). Pathways to prevention: Closing the gap in indigenous suicide intervention pathways [Conference paper]. 14th National Rural Health Conference, Cairns, QLD, Australia. Retrieved from http://www.ruralhealth.org.au/14nrhc/sites/default/files/BushraNasir_E5.pdf

Persaud, S., Rosenthal, L., & Arora, G. P. (2019). Culturally informed gatekeeper training for youth suicide prevention in Guyana: A pilot examination. School Psychology International, 40(6), 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034319879477

Pollock, N. J., Naicker, K., Loro, A., Mulay, S., & Colman, I. (2018). Global incidence of suicide among indigenous peoples: A systematic review. BMC Medicine, 16(1), Article 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1115-6

Quinnett, P. (2011). Question, persuade, refer (QPR) training manual (3rd ed.). QPR Institute.

Rasmus, S. M. (2014). Indigenizing CBPR: Evaluation of a community-based and participatory research process implementation of the Elluam Tungiinun (towards wellness) program in Alaska. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9653-3

Sheehan, L., Oexle, N., Armas, S. A., Wan, H. T., Bushman, M., Glover, T., & Lewy, S. A. (2019). Benefits and risks of suicide disclosure. Social Science and Medicine, 223, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.023

Skerrett, D. M., Gibson, M., Darwin, L., Lewis, S., Rallah, R., & De Leo, D. (2018). Closing the gap in aboriginal and Torress Strait Islander youth suicide: A social-emotional wellbeing service innovation project. Australian Psychologist, 53(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12277

Strickland, C. J., & Cooper, M. (2011). Getting into trouble: Perspectives on stress and suicide prevention among Pacific Northwest Indian youth. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659611404431

Sweetland, A. C., Pala, A. N., Mootz, J., Kao, J. C.-W., Carlson, C., Oquendo, M. A., Cheng, B., Belkin, G., & Wainberg, M. (2019). Food insecurity, mental distress and suicidal ideation in rural Africa: Evidence from Nigeria, Uganda and Ghana. Social Psychiatry, 65(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764018814274

Thornton, V. J., Asanbe, C. B., & Denton, E. D. (2018). Clinical risk factors among youth at high risk for suicide in South Africa and Guyana. Depression & Anxiety, 36(5), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22889

Viswanathan, M., Ammerman, A., Eng, E., Garlehner, G., Lohr, K. N., Griffith, D., Rhodes, S., Samuel-Hodge, C., Maty, S., Lux, L., Webb, L., Sutton, S. F., Swinson, T., Jackman, A., & Whitener, L. (2004). Community-based participatory research assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 99, 1–8. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11852/

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf?sequence=1&IsAllowed=y

Yuen, N. Y. C., Yahata, D., & Nahulu, A. (1999). Native Hawaiian youth suicide prevention project: A manual for gatekeeper trainees. Honolulu: Hawai‘i Department of Health, Injury Prevention and Control, emergency medical. Services Systems, Material and Child Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Peterson, H.C., Denton, Eg. (2021). Suicide Prevention Through Community Capacity Building in Resource-Poor Areas and Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). In: Miranda, R., Jeglic, E.L. (eds) Handbook of Youth Suicide Prevention. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82465-5_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82465-5_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-82464-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-82465-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)