Abstract

HIV stigma is a critical barrier to HIV prevention and care. This study evaluates the psychometric properties of the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale (HIV-SMS) among people living with HIV (PLHIV) in central Uganda and tests the underlying framework. Using data from the PATH/Ekkubo study, (n = 804 PLHIV), we assessed the HIV-SMS’ reliability and validity (face, content, construct, and convergent). We used multiple regression analyses to test the HIV-SMS’ association with health and well-being outcomes. Findings revealed a more specific (5-factor) stigma structure than the original model, splitting anticipated and enacted stigmas into two subconstructs: family and healthcare workers (HW). The 5-factor model had high reliability (α = 0.92–0.98) and supported the convergent validity (r = 0.12–0.42, p < 0.01). The expected relationship between HIV stigma mechanisms and health outcomes was particularly strong for internalized stigma. Anticipated-family and enacted-family stigma mechanisms showed partial agreement with the hypothesized health outcomes. Anticipated-HW and enacted-HW mechanisms showed no significant association with health outcomes. The 5-factor HIV-SMS yielded a proper and nuanced measurement of HIV stigma in central Uganda, reflecting the importance of family-related stigma mechanisms and showing associations with health outcomes similar to and beyond the seminal study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV-related stigma is a major challenge worldwide for people living with HIV (PLHIV) and a significant risk factor for poor HIV testing and treatment outcomes [1,2,3]. It has been linked to delayed presentation for care [4], poor physical and mental health [5, 6], lowered CD4 count [1] and poor ART adherence [1, 6, 7] and access to treatment [1, 6]. Therefore, addressing HIV stigma is of paramount importance to achieving UNAIDS goals of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030 [8], especially in Uganda, where there are 1.4 million PLHIV and the number of PLHIV increased 27% over the past decade [9].

Despite Uganda’s extensive efforts to combat HIV, such as through free universal HIV testing and treatment, HIV-related stigma continues to contribute to poor HIV outcomes among PLHIV. Duff et al. [10] observed that HIV stigma is responsible for Ugandan women's non-disclosure to partners, creating barriers to HIV care and treatment. Bogart et al. [11] showed that fisherfolk living with HIV in Uganda experienced stigma differently depending on whether or not they were linked to care, with those not linked expressing fear of social isolation. Additionally, Bogart et al. [11] and Buregyeya et al. [12] noted that fear of being seen in HIV health facilities was a barrier to accessing health care among PLHIV in Uganda, sometimes leading them to travel long distances to access care.

While there is consensus that reducing stigma is essential to ending the HIV epidemic, the literature's diversity of scales has led to different operationalizations of HIV stigma. This, in turn, obscures the identification and comparison of how PLHIV experience stigma and how stigma affects their health. Understanding specific facets of stigma and its health implications are essential for well-designed and efficacious HIV interventions targeting prevention, viral load suppression, and well-being.

Scales that measure HIV stigma have been documented since 1988 [13]. However, a 2009 literature review highlighted the need to understand and measure how HIV stigma is experienced by both PLHIV and people not living with HIV [14], leading to the development of the HIV stigma mechanisms framework. The framework proposes three distinct HIV stigma mechanisms (internalized, anticipated, and enacted stigma) by which PLHIV process deleterious experiences and hypothesizes that each type of stigma is associated with unique health outcomes. Specifically, internalized stigma or “the degree to which PLHIV endorse the negative beliefs and feelings associated with HIV/AIDS about themselves” [14] is associated with affective and behavioral health and well-being outcomes (e.g., helplessness and medical care visits) [15]. Enacted stigma, or “the degree to which PLHIV believe they have experienced prejudice and discrimination from others in their community” [14] is associated with physical health outcomes (e.g., CD4 count) [15]. Anticipated stigma, or “the degree to which PLHIV expect they will experience prejudice and discrimination from others in the future” [14] is associated with behavioral and physical health outcomes (e.g., antiretroviral adherence and chronic illness) [15].

In 2013, Earnshaw et al. advanced the HIV stigma mechanisms framework by developing the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale (HIV-SMS) to measure HIV stigma among PLHIV. However, to date, we are aware of only three published studies that have evaluated this scale's psychometric properties [15,16,17], all analyzing samples of PLHIV from high-resource countries (i.e., the USA and Sweden). Therefore, we seek to add to the HIV stigma measurement literature by (a) evaluating the psychometric properties of the HIV-SMS and (b) testing the HIV stigma mechanisms framework in a sample of PLHIV in central Uganda. By doing so, we aim to broaden the spectrum of the scale's applicability, especially among East African populations disproportionately affected by HIV [18]. This study's findings have the potential to support HIV practitioners, researchers, and policymakers in understanding the types of stigmas underlying their patients/populations and fostering tailored interventions to positively impact PLHIV’s health and well-being.

Methods

First, we sequentially evaluated the psychometric properties of the HIV-SMS among PLHIV in Uganda, assessing its (a) face and content validity, (b) construct validity, (c) reliability, and (d) convergent validity. Second, we tested the HIV stigma mechanisms framework by investigating the associations between each HIV-SMS subconstruct and their hypothesized health and well-being outcomes (affective, behavioral, and physical).

Study Population and Data Source

We used data collected between November 2015 and March 2020 as part of the PATH (Providing Access to HIV Care)/Ekkubo study, a cluster randomized controlled trial of an enhanced linkage to HIV care intervention. PATH/Ekkubo was conducted in central Uganda (Butambala, Mpigi, Mityana, and Gomba districts) in the context of community-wide home-based HIV testing. Villages (cluster unit) were randomized and allocated to the intervention or standard-of-care (control) arms.

All participants were verbally screened for eligibility: speaking Luganda (the most frequently spoken language in the study districts) or English, being 18 to 59 years old or an emancipated minor, accepting HIV testing, and being a resident of the household. Then they provided written (or thumb-printed) informed consent and completed the baseline questionnaire [19]. The current study used baseline data from participants who reported being previously diagnosed with HIV and were confirmed HIV-positive.

Measures

Data were collected by trained interviewers using interviewer-administered questionnaires [19]. All questions were translated from English into Luganda, back-translated into English, and then modified to ensure equivalence in meaning. Appendix A provides a table with the HIV-SMS questions in English and Luganda.

The HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale (HIV-SMS)

The HIV-SMS is a 24-item instrument designed to measure stigma among PLHIV. The scale conceptualizes three distinct mechanisms by which PLHIV process deleterious experiences, measured by a set of items rated along a 5-point Likert scale. Six items with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” cover internalized stigma and are preceded by the question: “How do you feel about being HIV-positive?” Nine items with responses ranging from “very unlikely” to “very likely” describe anticipated stigma and are preceded by the question: “How likely is it that people will treat you in the following ways in the future because of your HIV status?” Nine items with responses ranging from “never” to “very often” cover enacted stigma and are preceded by the question: “How often have people treated you this way in the past because of your HIV status?” Table 3 presents all HIV-SMS items.

Sociodemographic

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, marital status, education, religion, and wealth status (measured by an index of participants' household components and possessions).

HIV Status and Health-Related Outcomes

Self-reported HIV status was confirmed with HIV testing, following the 2015 World Health Organization's (WHO) algorithm for high-prevalence HIV settings [20]. Participants' HIV-related clinical characteristics included measures of affective, behavioral, and physical health.

Affective Health and Well-Being

The Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) [21] was used to test the hypothesized association between affective health and internalized stigma [15] and evaluate convergent validity. Previous studies have considered depression theoretically associated with HIV stigma among PLHIV [22,23,24] and used this variable to test convergent validity in Uganda [25]. The CES-D-10 has been validated in South Africa [26] and used with PLHIV in Uganda [27]. It is a 10-item, self-rating scale with responses ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time/less than 1 day) to 3 (mostly or all of the time/5–7 days) and a threshold sum score of 10 or higher, indicating the presence of significant depressive symptoms [28]. The CES-D-10 presented high reliability in our sample (Cronbach's alpha = 0.9; McDonald's Omega = 0.9).

Behavioral Health and Well-being

We calculated two behavioral health measures: (1) months since the last HIV clinic visit, based on the question “When was the last time you attended the HIV clinic?” and baseline/enrollment date, and (2) the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) index [29]. Studies have shown that alcohol use is a behavior associated with HIV stigma [30, 31], and the AUDIT-C has been validated in Namibia [32] and used with PLHIV in Uganda [33]. It is a 3-item, self-rating scale with responses ranging along a 5-point Likert scale. A sum score of 4 for men and 3 for women indicates alcohol misuse [29]. The AUDIT-C presented high reliability in our sample (Cronbach's alpha = 0.7; McDonald's Omega = 0.7). Both measures were used to evaluate the hypothesized association between behavioral health and internalized and anticipated stigma [15].

Physical Health

We included three physical health measures: (1) self-reported CD4 levels, grouped as: “less or equal to 500 cell/mm3” and “greater than 500 cell/mm”, (2) the number of significant health problems, based on the question: “How many times in the past 6 months have you experienced significant physical medical problems?,” and (3) the number of hospitalizations, based on the question “How many times in the past 6 months have you been admitted/hospitalized for physical medical problems?” Each measure was used to test the hypothesized association between physical health and anticipated and enacted stigma [15].

Analytic Approach: Psychometric Analysis of the HIV-SMS

All statistical analyses were performed in R environment v.4.0.2 [36] using the following packages: psych v.2.0.12 [37], ltm v.1.1.1 [38], KernSmoothIRT v.6.4 [39], and lme4 v.1.1.26 [40]. Analyses were considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

Face and Content Validity

The HIV-SMS was analyzed by a multicultural (American and Ugandan) team of experts. They reviewed and evaluated the scale for comprehensiveness, redundancy, and cultural appropriateness. The Ugandan experts lived in Uganda and were aware of the local culture.

Construct Validity

We used exploratory data analysis to identify patterns of missing values, the correlation between items, item-level means, and standard deviation. We used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the HIV-SMS latent structure, given it has only been evaluated in three developed countries outside of Sub-Saharan Africa [15, 16, 41].

The optimal EFA solution was selected based on the following statistics: Parallel Analysis [42], Velicer's Minimum Average Partial criterion (MAP) [43], and the goodness of fit statistics [corrected root mean square of the residuals (RMSR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)]. Ultimately, we used a bifactor model (omega hierarchical statistic) to check the selected model assumptions versus the theoretical mechanisms proposed by the scale's authors. The choice of the optimal factor solution considered the proposed HIV stigma mechanisms’ theoretical subconstructs, regional culture, and statistical findings. We used polychoric correlations in our EFA and the oblique rotation method to allow the factors to correlate. Only HIV-SMS items with a minimum factor loading of 0.30 were included in the selected solution.

We used a Non-parametric Item Response Model (NP-OCC) to examine the ability of the HIV stigma mechanism items to discriminate across the 5 response options. The Parametric Item Response Model (P-OCC) was used to estimate the discrimination and severity of each item within its assigned subscale.

Reliability

We calculated Cronbach's alpha [44] and McDonald’s Omega [45] to assess how closely related the HIV-SMS items were as a group. Correlations among the originally HIV-SMS hypothesized subconstructs (internalized, anticipated, and enacted) were also evaluated.

Convergent Validity

Convergent validity was evaluated by calculating Pearson correlations (r) between the HIV stigma subscales unveiled by EFA and depressive symptoms (CES-D-10).

HIV Stigma Mechanisms Framework: Testing the Associations with Health and Well-Being Outcomes

We used bivariate correlations and multivariate multiple linear regression models to test the hypothesized associations between the three health outcomes (affective, behavioral, and physical health) and specific mechanisms of HIV stigma among PLHIV [15]. Each model controlled for social demographic characteristics.

Ethics

Approval for the PATH/ Ekkubo study was obtained from the institutional review boards of San Diego State University and Makerere University School of Public Health. Clearance was obtained from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Results

Sample Characteristics

As indicated in Table 1, participants’ average age was 37.96 years (SD = 10.28); 78.23% (n = 629) were women versus 21.77% (n = 175) men. Many were married or living together most of the time (42.04%) or divorced (31.22%). The majority reported primary-level education (68.91%).

The average level of depressive symptoms (CES-D-10) was low (M = 7.36, SD = 6.81; range 0–30). Similarly, the average HIV stigma score (possible range from 1–5) for each mechanism was low: the internalized stigma mechanism presented an average of 2.16 (SD = 0.86), the anticipated stigma averaged 1.86 (SD = 0.62), and the enacted stigma mechanism average was 1.54 (SD = 0.62).

Correlations Between HIV-SMS Items

Within the enacted and anticipated stigma HIV-SMS subscales, we observed higher correlations among items related to family and healthcare workers. Items also presented higher overall correlations when within the same subscale. The minimum correlation was between the enacted stigma item “healthcare workers have treated me with less respect” and the anticipated stigma item “Family members will avoid me” (r = 0.27, p < 0.01). The maximum correlation was between the enacted stigma items “Family members have looked down on me” and “Family members have avoided me” (r = 0.99, p < 0.01). All correlations are displayed in Fig. 1.

Psychometric Analysis of the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale

Face and Content Validity

The PATH/Ekkubo study's multicultural team of experts (from the USA and Uganda) reviewed the HIV-SMS for instrument meaningfulness and relevance to the central Ugandan cultural context. Seven of the twenty-four HIV-SMS items were trimmed for not being relevant in the Uganda setting. These items were excluded before data collection and, therefore, are not included in the analyses. Specifically, three items were excluded from the anticipated and enacted mechanisms because they asked about community/social workers, and such providers do not exist in the Ugandan context: (1) “Community/social workers will not take [have not taken] my needs seriously”; (2) “Community/social workers will discriminate [have discriminated] against me”; (3) “Community/social workers will deny [have denied] me services.” One item was excluded from the internalized stigma mechanism (“Having HIV is disgusting to me”) because the team did not understand or interpret the item as having an equivalent meaning or expression in Luganda as in English.

The interviewers read the questions to participants to avoid possible misunderstandings. Each section was introduced with explaining statements, for example: "Next, I want you to tell me how much you agree with the statements I read", before the internalized items.

Construct Validity

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

All HIV stigma mechanism items included in our EFA are presented in Table 2. The underlying structure of the HIV-SMS was originally grouped into three factors: internalized, enacted, and anticipated stigma [15]. However, based on the statistics used to evaluate the model goodness of fit, we selected a 5-factor model. The Velicer’s MAP, BIC, cumulative explained variance, and RMSEA criteria suggested a 5-factor solution, with the five factors explaining 85% of the sample variance (Fig. 2).

As indicated in Table 2, in the 5-factor model, all internalized stigma items loaded strongly on the expected theoretical subconstruct, with loadings ranging from 0.77 (“I feel ashamed of having HIV”) to 0.95 (“Having HIV makes me feel unclean”). However, the anticipated and enacted stigma items split into two subconstructs related to “family” and “healthcare workers.” We defined these new subconstructs as (1) anticipated-family; (2) anticipated-healthcare workers (anticipated-HW); (3) enacted-family; (4) enacted-healthcare workers (enacted-HW).

The anticipated-family stigma subscale, with factor loadings ranging from 0.87 to 1.01, encompassed items related to PLHIV’s expectations on how their families will treat them because of their HIV. Whereas the anticipated-HW stigma subscale, with factor loadings ranging from 0.93 to 0.98, comprised items related to PLHIV’s expectations of how healthcare workers will treat them because of their HIV status. The mean score for anticipated-family stigma anticipated-HW stigma was 2.02 (SD = 0.88) and 1.69 (SD = 0.62), respectively.

The enacted-family subscale encompassed items related to PLHIV’s experiences of how they were treated by their families because of their HIV status and presented loadings ranging from 0.78 to 1.00. Conversely, the enacted-HW subscale comprised items related to PLHIV’s experiences of how healthcare workers treated them because of their status; with factor loadings ranging from 0.85 to 0.96. The mean enacted-family and enacted-HW stigma scores were 1.63 (SD = 0.78) and 1.46 (SD = 0.63), respectively.

We used bi-factor analysis to examine if the “family” and “healthcare workers” items within the enacted and anticipated stigma subscales could be grouped into two subscales: (1) “family,” comprising items related to treatment that PLHIV received from family and based on past experiences (enacted) and expectations (anticipated); (2) “healthcare workers,” comprising items related to treatment that PLHIV received from healthcare workers and based on past experiences (enacted) and expectations (anticipated). The Omega-hierarchical of the tentative “family” subscale was 0.68 and 0.70 for the tentative “healthcare workers” subscale, suggesting that, in both cases, a single subconstruct was insufficient to organize the items, reinforcing the 5-factor HIV-SMS solution for the current study population.

Item Response Model

The items' response frequency showed that all response options were used by participants to describe their HIV stigma, with “Strongly disagree” to “Disagree,” “Very unlikely” to “Unlikely,” and “Never” to “Not-often” as the most frequent options chosen (Table 3). The internalized stigma items had the highest percentage of “Strongly Agree,” reflecting the overall highest mean score among the three hypothesized mechanisms of the HIV stigma scale (Table 1).

The Nonparametric Option Characteristic curves for the 5-factor solution suggested no substantial evidence for regrouping any response option for any item (Online Appendix B). The discrimination and severity thresholds estimated by the Parametric Item Response model suggested that the items distinguished well between participants across the different HIV-SMS stigma subscales, with high discrimination estimates (above 1.4) for all items (Table 4).

Reliability

The Cronbach's alpha of the HIV-SMS 5-factor solution ranged from 0.92 (internalized) to 0.98 (anticipated-family), while the McDonald's Omega ranged from 0.95 (internalized) to 0.98 (anticipated-family). Table 3 presents all of Cronbach's alpha and McDonald’s Omega statistics. We also computed Cronbach's alpha for each subscale, after excluding items one by one. This analysis did not suggest a need to drop any items (Table 3). The overall reliability of the 5-factor HIV-SMS was analogously high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90; McDonald’s Omega = 0.91).

Convergent Validity

The Pearson correlation between the full 5-factor HIV-SMS and the CES-D-10 was 0.39 (p < 0.01). The maximum correlation was between the internalized HIV stigma mechanism and CES-D-10 (r = 0.42, p < 0.01), followed by enacted-family (r = 0.25, p < 0.01), anticipated-family (r = 0.24, p < 0.01), and anticipated and enacted-HW (both r = 0.12, p < 0.01).

Bivariate Analyses Among the HIV-SMS 5-Factor Solution

Bivariate analyses among the HIV-SMS 5-factor solution showed a maximum Pearson correlation of 0.47 (p < 0.01) between anticipated-HW and enacted-HW, followed by enacted-family and enacted-HW and anticipated-family and enacted-family (both r = 0.46, p < 0.10). The association between anticipated-family and enacted-HW presented the minimum correlation of 0.19 (p < 0.01; Table 5).

HIV Stigma Mechanisms Framework: Testing the HIV Stigma Subconstructs Associations with Health Outcomes

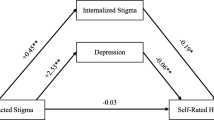

The multiple regression models testing the hypothesized associations between each HIV stigma mechanism and health outcomes are presented in Table 6. Many of the findings confirmed the bivariate association presented in Table 7. A comparison between the USA-based seminal work and our results is in Fig. 3, and our findings for the HIV-SMS framework hypothesized associations are detailed below:

-

a.

Internalized stigma & affective and behavioral health As hypothesized, internalized stigma was positively associated with depressive symptoms. An increase of 1 unit in internalized stigma (range 1–5) was associated with an increase of b = 3.27 (95% CI 2.59–3.94, p < 0.01) in depressive symptoms (range 0–30) and b = 0.46 (95% CI 0.08–0.84, p < 0.01) in “months since the last visit to an HIV clinic.” No statistically significant association between internalized stigma and with alcohol use was found. However, non-hypothesized associations involving the internalized stigma were also present. When examining associations between internalized stigma and physical health outcomes we found that higher levels of internalized stigma were associated with having a lower CD4 count (< 500 cell/mm3, aOR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.90, p < 0.01) and more significant health problems (b = 0.32, 95% CI 0.21–0.44, p < 0.01).

-

b.

Anticipated stigma & behavioral and physical health The hypothesized association between anticipated stigma and physical health outcomes was found, but only when examining the anticipated-family stigma mechanism. Anticipated-family stigma was positively associated with number of hospitalizations, such that a one-unit increase in anticipated-family stigma (range 1–5) was associated with an increase of b = 0.06 in the number of hospitalizations (95% CI 0–0.11, p < 0.05). Regarding behavioral health, anticipated-HW stigma was uniquely associated with alcohol use. However, different than hypothesized, higher levels of anticipated-HW stigma were linked to less alcohol use (b = − 0.66, 95% CI − 1.02–0.29, p < 0.01).

-

c.

Enacted stigma & physical health As hypothesized, enacted-family stigma was positively associated with number of hospitalizations (b = 0.09, 95% CI 0.02–0.16, p < 0.01). However, we also found a non-hypothesized positive association between enacted-family stigma and depressive symptoms: a one-unit increase in enacted-family stigma (range 1–5) was associated with an increase of b = 1.15 in depressive symptoms (95% CI 0.31–1.99, p < 0.01). Additionally, contrary to our hypothesis, enacted-HW stigma was negatively associated with number of significant health problems (b = − 0.18, 95% CI − 0.35–0, p < 0.05).

Table 6 Multiple Associations between the health outcomes with the 5-factor solution for the HIV-Stigma Mechanism Scale Table 7 Correlation (r), part II

Discussion

This study advances previous research on HIV stigma measures by evaluating the psychometric properties of the HIV-SMS. We tested and adapted the HIV-SMS for PLHIV in central Uganda, a country disproportionately affected by HIV. We tested the final scale associations with health outcomes hypothesized in the original HIV stigma mechanisms framework [15]. Interestingly, we found comparable rates of HIV stigma as reported in the seminal work conducted in the USA [15]. On average, overall rates of self-reported HIV stigma were low, with enacted stigma being the least reported and internalized stigma the most reported.

However, unlike prior research, findings from our analyses exploring the HIV-SMS' latent structure pointed to more nuanced HIV stigma mechanisms among PLHIV in central Uganda. Specifically, our analyses unveiled that the HIV-SMS’ enacted and anticipated stigma subscales should split into two: one subscale related to family members and the other associated with healthcare workers. This finding resulted in a newly configured HIV-SMS composed of five (versus three) stigma subscales: internalized, anticipated-family, anticipated-HW, enacted-family, and enacted-HW.

Within the resultant 5-factor model, the subscales with higher correlations were associated with the same source agents of stigma: anticipated-family and enacted-family were positively and strongly correlated, as well as anticipated-HW and enacted-HW. These findings suggest that HIV stigma is processed differently among PLHIV in central Uganda and varies depending on the source agent. HIV is a “family disease”; consequently, the family is an essential resource for prevention, care, and wellness [46]. Although some families in Uganda may abandon PLHIV and be a source of discrimination, they may also help PLHIV to develop a more positive sense of themselves [47].

The literature on substance use-related stigma also shows an agent-based structure for anticipated and enacted stigma mechanisms. Thus, our study findings may be generalizable to other stigma types outside of HIV-related stigma. For example, similar to our findings, Smith et al. [48] and Smith et al. [49] found factor solutions that split anticipated and enacted stigma subconstructs into family and healthcare workers for the Substance Use and Methadone Maintenance Treatment Stigma Mechanisms Scales (SU-SMS and MMT-SMS).

We also found similar results and limitations when testing the relationship between our HIV-SMS 5-factor solution and health outcomes as in the seminal work [15]. Internalized stigma had the strongest positive association with affective health (depressive symptoms) and was the only mechanism positively associated with the behavioral health outcome months since the last HIV clinic visit. Opposite than hypothesized, we found a negative association between internalized stigma and CD4 count (physical health). This counterintuitive finding could be due to recall bias, given that participants’ CD4 count was self-reported and the length of time since participants’ last CD4 count was not assessed. We also found a non-hypothesized positive association between internalized stigma and physical health (number of significant health problems), indicating that future research should explore this relationship, as it may parallel findings that depression is associated with chronic illness [50].

Like findings from the seminal HIV stigma mechanisms framework research [15], we found a positive association between anticipated and enacted family stigma and physical health (number of hospitalizations). However, we did not find support for the hypothesized association between anticipated (family or HW) with behavioral health (months since last HIV clinic visit and alcohol use). Researchers have found that PLHIV's fear of disclosing their serostatus to their family is linked to isolation and non-linkage to care [11]. Therefore, “months since last HIV clinic visit” may not be an appropriate measure to use with PLHIV experiencing family-related HIV stigma as they may not be receiving HIV care. Future research should encompass different HIV treatment access and adherence measures representing behavioral health constructs to explore this possibility. Furthermore, as time has evolved with differentiated care approaches in the Ugandan HIV healthcare system, patients who are stable on treatment may not need to go to the clinic for up to 6 months, making “months since the last clinic visit” as an indicator of potential lapses in care a difficult measure to apply universally to PLHIV in this context.

Anticipated and enacted healthcare worker stigma were not positively associated with any of the health outcomes considered in this study. Interestingly, the average stigma scores in both the anticipated-HW and enacted-HW subconstructs were, on average, 13% lower than their family counterparts. A possible explanation for this finding is that, given the higher rates of HIV, the duration of the epidemic, and greater initiatives to end the HIV epidemic in Uganda, such as through free universal test-and-treat [51], healthcare workers received more training and experience working with PLHIV. This additional training and exposure to PLHIV may have ultimately reduced discrimination from HIV healthcare workers. The negative association between enacted-HW and the number of significant health problems (physical health outcome) can also result from exposure to the health care system. If someone has more health problems and has sought more (outpatient) health care, they might be less fearful of stigma from healthcare workers.

Finally, we did not find a significant positive association between alcohol use (behavioral health) and any of the stigma mechanisms. This finding could be due to the samples' low rate of alcohol consumption (average of 1.59 on a scale ranging from 0 to 12), indicating that future research in Uganda should oversample PLHIV with high levels of alcohol consumption to ensure adequate representation of this high-risk population.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study has several strengths, including being the first to examine the HIV-SMS psychometric properties using a sample from a resource-limited setting. Additionally, the study analyses were conducted using a representative community-based sample of PLHIV in central Uganda and tested relationships with health measures not explored in prior work. However, the study findings must be interpreted cautiously, given certain limitations.

First, we used cross-sectional data to conduct the analyses. As HIV becomes more familiar to people, the level of HIV stigma experienced may have decreased over time [52]. Thus, to broaden our understanding of the HIV stigma mechanisms framework and specify how each stigma mechanism is associated with health and well-being outcomes, it would be important to consider longitudinal designs, especially with newly diagnosed participants.

Second, this is a secondary analysis of the PATH/Ekkubo study data; the variables used may not be optimal for this specific analysis. For example, because HIV stigma was only measured using the HIV-SMS in the PATH/Ekkubo study, we did not test convergent validity using other HIV stigma measurement instruments. Relatedly, we did not assess other sources of HIV stigma outside of family and healthcare workers, such as HIV stigma from community members. Community-level stigma experienced by PLHIV in Uganda is not uncommon. For example, one study in Uganda found that PLHIV prefer to look for HIV treatment in facilities not close to their home for fear of being stigmatized by their community members [53]. Future HIV stigma research, especially those conducted in central Uganda or similar settings, should include measures of community-level anticipated and enacted stigma, as well as other sources of stigma (e.g., anticipated/enacted stigma from co-workers and faith-based organizations).

Conclusion

Our 5-factor solution for the HIV-SMS is a nuanced, reliable, and valid instrument for measuring HIV stigma among PLHIV in central Uganda and potentially for other sub-Saharan African regions sharing similar cultures. The specificity of the 5-factor model can help inform the growing body of interventions targeting HIV stigma [54, 55] not only by providing improved HIV stigma measurement but also distinguishing the source agents of stigma in the HIV dynamic, specifically families versus healthcare workers. Our psychometric analysis and framework testing reinforce the HIV-SMS’ generalizability and the relationship between HIV stigma and PLHIV’s health and well-being. It also expands our knowledge of health and well-being outcomes associated with HIV stigma by testing health outcomes not explored in prior research.

Data Availability

An appendix is provided with the HIV Stigma Mechanism Scale questions in English and Luganda, and the non-parametric option characteristic curves (NP-OCC) for the scale revised five subconstructs.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Armoon B, Higgs P, Fleury MJ, Bayat AH, Moghaddam LF, Bayani A, et al. Socio-demographic, clinical and service use determinants associated with HIV related stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1004.

Kalichman SC, Shkembi B, Wanyenze RK, Naigino R, Bateganya MH, Menzies NA, et al. Perceived HIV stigma and HIV testing among men and women in rural Uganda: a population-based study. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(12):e817–24.

Kiene SM, Sileo K, Wanyenze RK, Lule H, Bateganya MH, Jasperse J, et al. Barriers to and acceptability of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling and adopting HIV-prevention behaviours in rural Uganda: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(2):173–87.

Gesesew HA, Tesfay Gebremedhin A, Demissie TD, Kerie MW, Sudhakar M, Mwanri L. Significant association between perceived HIV related stigma and late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173928.

Logie C, Gadalla TM. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):742–53.

Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7): e011453.

Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, Vervoort SC, Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Richter C, et al. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. 2014;14.

UNAIDS. Understanding Fast-Track: Accelarating action to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/201506_JC2743_Understanding_FastTrack_en.pdf

UNAIDS. Country factsheets, UGANDA - 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda

Duff P, Kipp W, Wild TC, Rubaale T, Okech-Ojony J. Barriers to accessing highly active antiretroviral therapy by HIV-positive women attending an antenatal clinic in a regional hospital in western Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(1):37–37.

Bogart LM, Naigino R, Maistrellis E, Wagner GJ, Musoke W, Mukasa B, et al. Barriers to Linkage to HIV Care in Ugandan Fisherfolk Communities: A Qualitative Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2464–76.

Buregyeya E, Naigino R, Mukose A, Makumbi F, Esiru G, Arinaitwe J, et al. Facilitators and barriers to uptake and adherence to lifelong antiretroviral therapy among HIV infected pregnant women in Uganda: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):94.

Pleck JH, O’donnell L, O’donnell C, Snarey J. AIDS-Phobia, Contact with AIDS, and AIDS-Related Job Stress in Hospital Workers. J Homosex. 1988;15(3–4):41–54.

Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77.

Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV Stigma Mechanisms and Well-Being Among PLWH: A Test of the HIV Stigma Framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95.

Belenko S, Dembo R, Copenhaver M, Hiller M, Swan H, Albizu Garcia C, et al. HIV Stigma in Prisons and Jails: Results from a Staff Survey. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):71–84.

Reinius M, Wiklander M, Wettergren L, Svedhem V, Eriksson LE. The Relationship Between Stigma and Health-Related Quality of Life in People Living with HIV Who Have Full Access to Antiretroviral Treatment: An Assessment of Earnshaw and Chaudoir’s HIV Stigma Framework Using Empirical Data. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(12):3795–806.

Parker E, Judge MA, Macete E, Nhampossa T, Dorward J, Langa DC, et al. HIV infection in Eastern and Southern Africa: Highest burden, largest challenges, greatest potential. South Afr J HIV Med [Internet]. 2021 May 28 [cited 2022 Oct 14];22(1). Available from: http://www.sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/HIVMED/article/view/1237

Kiene SM, Kalichman SC, Sileo KM, Menzies NA, Naigino R, Lin CD, et al. Efficacy of an enhanced linkage to HIV care intervention at improving linkage to HIV care and achieving viral suppression following home-based HIV testing in rural Uganda: study protocol for the Ekkubo/PATH cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):460.

World Health Organization. WHO RECOMMENDATIONS TO ASSURE HIV TESTING QUALITY [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/179521/WHO_HIV_2015.15_eng.pdf?sequence=5

Björgvinsson T, Kertz SJ, Bigda-Peyton JS, McCoy KL, Aderka IM. Psychometric Properties of the CES-D-10 in a Psychiatric Sample. Assessment. 2013;20(4):429–36.

Onyebuchi-Iwudibia O, Brown A. HIV and depression in Eastern Nigeria: The role of HIV-related stigma. AIDS Care. 2014;26(5):653–7.

Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, Bode R, Peterman A, Heinemann A, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585–95.

Ashaba S, Cooper-Vince CE, Vořechovská D, Rukundo GZ, Maling S, Akena D, et al. Community beliefs, HIV stigma, and depression among adolescents living with HIV in rural Uganda. Afr J AIDS Res. 2019;18(3):169–80.

Jeyaseelan L, Kumar S, Mohanraj R, Rebekah G, Rao D, Manhart LE. Assessing HIV/AIDS Stigma in South India: Validation and Abridgement of the Berger HIV Stigma Scale. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):434–43.

Baron EC, Davies T, Lund C. Validation of the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):6.

Kaharuza FM, Bunnell R, Moss S, Purcell DW, Bikaako-Kajura W, Wamai N, et al. Depression and CD4 Cell Count Among Persons with HIV Infection in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(S1):105–11.

Andresen E, Malmgren J, Carter W, Patrick D. Screening for depression in well older adults- evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine; 1993.

Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a Brief Screen for Alcohol Misuse in Primary Care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208–17.

Felker-Kantor EA, Wallace ME, Madkour AS, Duncan DT, Andrinopoulos K, Theall K. HIV Stigma, Mental Health, and Alcohol Use Disorders among People Living with HIV/AIDS in New Orleans. J Urban Health. 2019;96(6):878–88.

Wardell JD, Shuper PA, Rourke SB, Hendershot CS. Stigma, Coping, and Alcohol Use Severity Among People Living With HIV: A Prospective Analysis of Bidirectional and Mediated Associations. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(9):762–72.

Seth P, Glenshaw M, Sabatier JHF, Adams R, Du Preez V, DeLuca N, et al. AUDIT, AUDIT-C, and AUDIT-3: Drinking Patterns and Screening for Harmful, Hazardous and Dependent Drinking in Katutura, Namibia. Matsuo K, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 Mar 23;10(3):e0120850.

Wandera B, Tumwesigye NM, Nankabirwa JI, Mafigiri DK, Parkes-Ratanshi RM, Kapiga S, et al. Efficacy of a Single, Brief Alcohol Reduction Intervention among Men and Women Living with HIV/AIDS and Using Alcohol in Kampala, Uganda: A Randomized Trial. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care JIAPAC. 201716(3):276–85.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report - Supplemental Report [Internet]. 2011. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-16-1.pdf

Aberg JA, Kaplan JE, Libman H, Emmanuel P, Anderson JR, Stone VE, et al. Primary Care Guidelines for the Management of Persons Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2009 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(5):651–81.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 May 31]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

Revelle W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research [Internet]. Northwestern University; 2021. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

Rizopoulos D. ltm: An R package for Latent Variable Modelling and Item Response Theory Analyses [Internet]. Journal of Statistical Software; 2006. Available from: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v17/i05/

Wand MP, Jones MC, Ripley B. Kernel Smoothing [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/KernSmooth/KernSmooth.pdf

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2021 Apr 3];67(1). Available from: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v67/i01/

Lindberg MH, Wettergren L, Wiklander M, Svedhem-Johansson V, Eriksson LE. Psychometric Evaluation of the HIV Stigma Scale in a Swedish Context. Federici S, editor. PLoS ONE. 2014 Dec 18;9(12):e114867.

Dinno A. Exploring the Sensitivity of Horn’s Parallel Analysis to the Distributional Form of Random Data. Multivar Behav Res. 2009;44(3):362–88.

Velicer WF. Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika. 1976;41(3):321–7.

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–5.

McDonald RP. Test theory: a unified treatment. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1999. 485 p.

Pequegnat W, Bauman LJ, Bray JH, DiClemente R, DiIorio C, Hoppe SK, et al. Measurement of the Role of Families in Prevention and Adaptation to HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2001;5(1):1–19.

Takada S, Weiser SD, Kumbakumba E, Muzoora C, Martin JN, Hunt PW, et al. The Dynamic Relationship Between Social Support and HIV-Related Stigma in Rural Uganda. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(1):26–37.

Smith LR, Earnshaw VA, Copenhaver MM, Cunningham CO. Substance use stigma: Reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:34–43.

Smith LR, Mittal ML, Wagner K, Copenhaver MM, Cunningham CO, Earnshaw VA. Factor structure, internal reliability and construct validity of the Methadone Maintenance Treatment Stigma Mechanisms Scale (MMT-SMS). Addiction. 2020;115(2):354–67.

Kagee A. Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety among a Sample of South African Patients Living with a Chronic Illness. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(4):547–55.

Uganda Ministry of Health. Consolidated Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda [Internet]. Kampala; 2016. Available from: http://library.health.go.ug/publications/hivaids/consolidated-guidelines-prevention-and-treatment-hiv-uganda

Fauk NK, Ward PR, Hawke K, Mwanri L. HIV Stigma and Discrimination: Perspectives and Personal Experiences of Healthcare Providers in Yogyakarta and Belu, Indonesia. Front Med. 2021;12(8): 625787.

Akullian AN, Mukose A, Levine GA, Babigumira JB. People living with HIV travel farther to access healthcare: a population-based geographic analysis from rural Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20171.

Ma PHX, Chan ZCY, Loke AY. Self-Stigma Reduction Interventions for People Living with HIV/AIDS and Their Families: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):707–41.

Andersson GZ, Reinius M, Eriksson LE, Svedhem V, Esfahani FM, Deuba K, et al. Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(2):e129–40.

Funding

The parent study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant R01MH106391 awarded to Susan M. Kiene and Rhoda K. Wanyenze. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The original study was conceived and undertaken by SMK and RKW. This manuscript presents secondary data analysis, which was completed by AA. AA, SMK, and INO interpreted the study findings. The manuscript was drafted by AA with SMK, INO, RKW, KSC, ME, RN, and CDL revising the drafted text. All authors provided final approval for the publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional (San Diego State University and Makerere University School of Public Health) and national research committee (Uganda National Council for Science and Technology) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Almeida, A., Ogbonnaya, I.N., Wanyenze, R.K. et al. A Psychometric Evaluation and a Framework Test of the HIV Stigma Mechanisms Scale Among a Population-Based Sample of Men and Women Living with HIV in Central Uganda. AIDS Behav 27, 3038–3052 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04026-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04026-y