Abstract

Stigma is a primary concern for people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS (PLWHA), and has great impact on their and their family members’ health. While previous reviews have largely focused on the public stigma, this systematic review aims to evaluate the impact of HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related self-stigma reduction interventions among PLWHA and their families. A literature search using eight databases found 23 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Five types of intervention approaches were identified: (1) psycho-educational intervention, (2) supportive intervention for treatment adherence (antiretroviral therapy), (3) psychotherapy intervention, (4) narrative intervention, and (5) community participation intervention. Overall, the reviewed articles suggested a general trend of promising effectiveness of these interventions for PLWHA and their family members. Psycho-educational interventions were the main approach. The results highlighted the need for more interventions targeting family members of PLWHA, and mixed-methods intervention studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to Erving Goffman (1963), stigma is “an undesirable or discrediting attribute that an individual possesses, thus reducing that individual’s status in the eyes of society” (p. 3) [1]. Stigma is a powerful social process that deeply rooted in social, cultural, and historical contexts [1]. The person who is stigmatized is a person “whose social identity calls his or her full humanity into question” (p. 349) [2]. It is a mark of shame or disgrace and influences how individuals perceive themselves and how they are perceived by others [3]. It creates a power imbalance and social inequality between the stigmatized and un-stigmatized groups. The consequences of stigma can be devastating; the literature shows that stigma can lead to family discord, social rejection, social isolation, health inequalities, worse health outcomes, and human rights violations [4,5,6].

Over 30 years ago, the first case of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was reported in the US in 1981 [7]. Advanced treatment of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV infection from an acute fatal disease into a manageable chronic condition. However, HIV/AIDS-related stigma remains prevalent among the general public worldwide [8, 9]. Due to ignorance, inaccurate information about HIV/AIDS, fear of casual transmission, and moral judgments of the behavior of those infected with HIV/AIDS [10,11,12], the public stereotypes and discriminates against people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) or who are at a high risk of contracting HIV/AIDS (i.e., men who have sex with men, sex workers, intravenous drug users) [13]. Various types of discriminatory behaviors have been widely reported, such as gossip [14], blaming [14, 15], rejection [14, 15], social isolation [14, 15], unemployment [16], verbal and physical abuse [17], mistreatment or refusal of treatment by health care providers [14], and violations of confidentiality [18]. Public stigma might result in negative physical, mental and social well-being of PLWHA.

Three types of self-stigma are most relevant to PLWHA: (1) enacted/experienced stigma, (2) anticipated/perceived stigma, and (3) internalized stigma [13, 19, 20]. Enacted/experienced stigma refers to the actual occurrence of discrimination or prejudice because of one’s HIV status [21]. Anticipated/perceived stigma refers to the expectation that PLWHA will experience stigma and discrimination from others [21]. Internalized stigma is the self-shame and negative self-image felt by individuals who have been diagnosed with HIV infection [21]. These types of stigma adversely affect the behaviors, physical and psychological health outcomes, and social functioning of PLWHA. Enacted and anticipated stigma could deter PLWHA from getting tested [22], from fear of revealing their HIV status to others [23], and prevent accessing health and social services [23, 24]. Subsequently, it could compromise adherence to ART [25], and could undermine efforts to prevent and control HIV epidemics. Internalized stigma could lead to poor mental health outcomes, such as anxiety [26], stress [27], depression [24], diminished self-efficacy [27], low self-esteem [3, 28], lower levels of social support [26], hopelessness [26], and even suicidal ideation [29]. Thus, in many circumstances, the consequences of the self-stigma outweigh the burden of the disease itself.

Family members of PLWHA who are related by blood, marriage, or other connections such as adoption, could also experience HIV/AIDS-related stigma from their association with a PLWHA, known as “courtesy stigma” (p. 30) [1]. Gossip, rejection, verbal abuse, violence, social isolation, and loss of identity have frequently been reported in the literature [30,31,32]. The dual burden of caring for a PLWHA, while at the same time managing stigma and discrimination, could also lead to a deterioration in the physical and mental health of family members [33, 34]. To avoid anticipated stigma, some family members restrict the disclosure of the PLWHA’s HIV status [34], which subsequently reduce the PLWHA’s chances of seeking social support and treatment.

Battling HIV/AIDS-related stigma is occurring globally [35,36,37]. Researchers have made significant efforts in developing and delivering HIV/AIDS-related stigma reduction interventions, and several reviews of HIV/AIDS-related interventions aimed to reduce public stigma have been published [38,39,40,41]. Given the significant impact of stigma on the health outcomes and access to health care of PLWHA and their family members, it is timely to review interventions to reduce HIV-related self-stigma among PLWHA and their family members. The expected primary outcome of such a review is to inform current best practice to reduce self-stigma related to HIV/AIDS, and the enhancement of psychologically-related secondary outcomes such as depression, stress, anxiety, self-efficacy, and self-esteem.

Methods

Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted using eight databases, including Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Sociological Abstracts, and ProQuest Dissertation and Theses from inception to May 2018. MeSH terms and/or keywords were used combing the following: HIV/AIDS (“HIV” or “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome” or “AIDS” or “people living with HIV AIDS” or “PLWHA” or “sexually transmitted infection” or “sexually transmitted diseases”), self-stigma (e.g., anticipated stigma, internalized stigma, enacted stigma, perceived stigma, self-esteem, social isolation), and intervention (e.g., “intervention” or “program” or “evidence-based” or “health education” or “train”* or “therapy”). A manual search of studies published in key journals on AIDS was conducted, including: AIDS, AIDS reviews, AIDS Patient Care and STDs, AIDS Care-Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, AIDS and Behavior, International Journal of STD and AIDS, AIDS Education and Prevention, and Journal of the International AIDS Society. A manual search for additional literature was also made from the reference list of all the retrieved articles and bibliographies of existing review articles. Details of the search strategies are presented in Supplementary Appendix I. The search was not limited to any year, as the first case of AIDS was diagnosed in 1981.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies fulfilling the following criteria were included: (1) the study focused on PLWHA or their family members, (2) the intervention study could either take a single approach among PLWHA or their family members, or take a dyadic approach between PLWHA and their family members, (3) the intervention was psychosocially, cognitively, or behaviorally oriented, (4) the intervention included a component on the reduction of HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma among PLWHA or their family members, (5) the study design was either experimental or quasi-experimental or pre–post design, (6) the intervention included a clear description of an HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma outcome measure or other psychologically-related outcomes measures, and (7) the study was published in English. Studies were excluded if the intervention: (1) was not focused on PLWHA and/or their family members, (2) was focused on reducing HIV/AIDS-related public stigma, (3) did not include self-stigma measurement, (4) was a conference abstract, or a review article, or a cross-sectional study, or a study that did not use an experimental design, or qualitative studies without any quantitative component, (5) was published in a language other than English.

Appraisal of Quality of the Methodology

Methodological quality and the reporting of all trials were assessed using the Downs and Black Quality Index Score, as this allows for the assessment of both randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental trials [42]. The Downs and Black Scale consists of 27 questions with a maximum score of 28 [43], relating to the quality of the reporting in the study, the external validity, internal validity (bias and confounding), and statistical power of the study. The scale has been shown to have high internal consistency concerning the total score (Kuder–Richardson 20 test: 0.89). Each paper was graded as “excellent” when rated 24 points or above, “good” when rated 19–23 points, “fair” when rated 14–18 points, or “poor” when rated 13 points or below.

Data Synthesis

No formal statistical analysis was performed due to the heterogeneity of the various measurements used to measure outcomes in the included studies. The characteristics of the studies and critical findings were extracted and tabulated according to author(s), year of publication, country where the study was conducted, aims of the study, study design, participants, intervention type and contents, theoretical basis of the intervention, method of the intervention, dosage of the intervention, measurement, and the main findings. The characteristics and key findings of these studies are summarized and categorized in Tables 1 and 2.

The sample size, mean, and standard deviation were extracted for each study at the pre-test, post-test, and the last follow-up time points. The short-term effect of the intervention compared the measures prior to and at the end of the intervention, and the long term effects compared the measures prior to intervention with at least 3-month follow-up time point. The effect size was extracted where data was provided in the studies. When unavailable, the effect size of individual RCT study was calculated by the difference between two mean values and the pooled standard deviation. The effect size for the individual quasi-experiment study with control groups was calculated by subtracting the mean change score in a control group from the mean change score in an intervention group, divided by the pooled standard deviation of the pre-test score [44]. The effect size (Cohen’s d) was defined as small, medium, and large when it was rated 0.2, 0.5, and ≥ 0.8, respectively [45]. A bias correction component was used to correct for bias when the sample size was smaller than 10 [44]. The effect sizes of one group pre–post interventions were not calculated. Also, the effect sizes were not presented for studies without sufficient data. The formulas are summarized in Appendix II.

Results

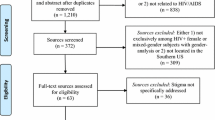

A total of 8778 publications were identified from the electronic databases. A total of 2655 publications were removed due to duplication, and the remaining 6123 abstracts were screened. Of these, 6073 publications were excluded for not meeting the criteria for inclusion. The full texts of the remaining 50 articles were examined in detail, and another 30 studies were further excluded with reasons. Finally, a total of 20 studies were considered eligible and were included in this review. In addition, three relevant studies were retrieved from a manual search of the reference lists of the included studies. Hence, a total of 23 studies were included in this review. A PRISMA flowchart on the process of searching through the literature and selecting the relevant studies is given in Fig. 1.

Quality of the Included Studies

Overall, the 23 studies that were included were considered to be of moderate quality, with Downs and Black Quality Index scores ranging from 11 to 24. Four studies were rated poor, 14 were rated fair, four were rated good, and one was rated excellent. The studies scored particularly poorly on the following items: lack of reporting of adverse events (22/23), unrepresentative of the subjects invited to participate in the study (20/23), failure to blind the subjects in the study (19/23) and the outcome assessor (20/23), lack of “data dredging” (23/23), failure to conceal the randomized intervention assignment from both patients and healthcare staff (20/23), and insufficient power to detect outcomes that were clinically significant (20/23).

A decision was made to not exclude four studies that had been rated as having poor methodology, due to their significant contributions to knowledge in the specific area. One study targeted HIV subgroups of gay and bisexual men [46]. Another study featured a health setting-based intervention targeting healthcare professional on both stigma and self-stigma [47]. The other two studies sought to replicate previous studies and explored the effectiveness of the intervention [48, 49]. Details of the appraisal of the quality of these studies are given in Table 3.

Study Participants

Only three studies were published in the 1990s, and the number increased from 7 in 2000–2009 to 13 in 2010–2017. Most of the included studies were conducted in North America (n = 12), followed by Africa (n = 6), Asia (n = 4), and South America (n = 1). The number of participants varied considerably in the included studies, from 5 in an investigation of an acceptance and compassion-based group intervention among HIV-positive men who identified as gay or bisexual [46] to 630 in an RCT that evaluated the effectiveness of a community-based ART adherence support intervention for adult PLWHA [50]. The participants were recruited from clinics or hospitals that provide HIV/AIDS services, or community settings. One study focused on young people newly diagnosed with HIV, two studies evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention among youth with HIV/AIDS and their caregivers, two studies were undertaken among family members and the spouse of the PLWHA, one study evaluated the effectiveness of the intervention on both health setting-based stigma and self-stigma among the nurse and the PLWHA as a team, one study involved PLWHA, their caregivers, and other community members. The other studies targeted adult PLWHA (n = 16). Eight of those studies exclusively recruited women, and one study only recruited men who identified as gay or bisexual. Seven studies specified the time since the HIV diagnosis. The loss to follow-up rate was reported in 18 studies and ranged from 0.0 to 64.7%. Details of the characteristics and key findings of these studies are summarized in Table 1.

The Theoretical Basis of the Interventions

Among the 23 studies, only ten interventions were developed with explicit theoretical foundations. Most studies used one theory or model, only three studies used multiple theories or models to inform the development of their intervention [46, 51, 52]. The majority of studies adopted cognitive and behavioral elements, including social learning theory [51, 53], social action theory [51], social cognitive theory [54], acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) incorporating ideas from compassion-focused therapy (CFT) [46], cognitive behavioral therapy [55], and empowerment principles [51]. Four studies adopted existing frameworks, such as the Maternal HIV Self-Care Symptoms management framework [56], the Comprehensive Health Seeking and Coping Paradigm (CHSCP) [57], the Freirian participatory education framework [58], and the Thomas and Rothman integrative framework [59]. Few studies provided detailed description of the theories or frameworks.

Intervention Approaches

Of the 23 included studies (n = 2211 participants), 10 were RCTs, seven were quasi-experimental studies with control group studies, and 6 were one group pre–post studies. The majority of the interventions were delivered through face-to-face methods, with the exception of three interventions, which were delivered via IPod Touch [60], telephone [59], and a radio program [58], respectively. Most of the studies were facilitated by trained professionals, such as research staff, social workers, or health care professionals, including nurses, psychologists, therapists, public health practitioners, and community healthcare workers. Five studies involved HIV-positive peer facilitators [47, 49, 50, 52, 53], and only one study was delivered by healthy lay women [57].

A broad range of intervention types were identified in the included studies, including psycho-educational intervention, support group interventions for treatment adherence (ART), psychotherapy intervention, narrative intervention, and community participation intervention. The contents of the interventions are presented in order of the popularity of the intervention.

Psycho-educational Intervention

The most common type of intervention was the psycho-educational intervention (n = 13), which adopted educational, skill building, empowerment, and social support approaches. The education focused particularly on providing information related to HIV/AIDS, safe health behaviors, managing negative feelings, coping with stigma, and building support networks. Skill building programs were provided for building a variety of skills, such as stress reduction [61, 62], leisure [62], relaxation [53], anger management [61], stigma coping [53], and decision-making skills [52]. Empowerment approach focused on enhancing participants’ self-esteem, self-efficacy, autonomy, family function and social relationships, human rights and anti-discriminatory laws [51]. Social support programs focused on providing emotional and informational support, such as establishing contact with peers [48, 51, 52], family members [61, 62], health care providers [47, 63], and on sharing experiences, emotions, and stigma-coping strategies. Four studies used an education-only approach [54, 58, 64, 65], and nine studies adopted two or three approaches, including education, skill building, empowerment, and social support [47, 48, 51,52,53, 56, 59, 61, 62].

Support Group Intervention for Treatment Adherence (ART)

Four studies evaluated the impact of a support group intervention for treatment adherence (ART) on PLWHA in resource-constrained settings [50, 57, 66, 67]. This type of intervention primarily aimed at addressing barriers and improving access to ART treatment adherence, and providing emotional, informational, nutritional and financial support. It assessed HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma as its secondary outcome. One study adopted a nurse-led ART, in which a nurse was responsible for supervising the taking of one dose of ART and providing individualized adherence support twice weekly for 6 months [66]. In the other three studies, the task of monitoring ART was shifted to peer-adherence supporters and community health workers, who had no professional qualifications but who had received training in HIV and ART adherence [50, 57, 67].

Psychotherapy Intervention

Psychotherapy approaches to reduce HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma were evaluated in four studies. Two studies used emotional writing disclosure to facilitate cognitive reorganization [49, 68]. The participants were asked to take 20 min on three consecutive days to write about the most traumatic events that they had experienced. One study assessed the effect of eight weekly sessions of ACT-based group therapy [46]. It emphasized defusion, acceptance, self-as-context, and the value aspect of the ACT. The participants were guided to reorganize feelings of shame and encouraged to consider the negative experiences associated with an HIV diagnosis, respond to those shame-based thoughts, and achieve psychological flexibility. One study evaluated the effect of eight weekly sessions of individual-based cognitive behavioral therapy [55], where a positive reframing technique was adopted to provide the participants with alternative interpretations of HIV and to promote more realistic and adaptive ways of thinking [55].

Narrative Intervention

One RCT inspired the HIV-positive women to overcome the challenges of self-stigma through a weekly 45-min narrative video titled “Maybe Someday: Voices of HIV-Positive Women” [60]. HIV-positive women (actresses) in the video shared their experiences of being HIV-infected women, their fears, the struggles that they experienced with disclosing their HIV status, the importance of communicating with people whom they trust, and the positive effect of disclosing their HIV status.

Community Participation Intervention

One community participation intervention empowered the community through increasing interactions among PLWHA, the PLWHA’s family members, and other community members; providing extensive information related to HIV/AIDS, and overcoming resource constraints by combining the intervention with a socioeconomic intervention [63].

The Dosage of the Intervention And Follow-Up Time Frame

The frequency, duration, and follow-up time of the interventions varied widely. The frequency of the interventions ranged from 2 to 22 sessions, with each session lasting from 60 min to 2 h. The support groups paid frequent home visits in supporting PLWHA’s ART adherence and their mental health. The number of home visits ranged from approximately 7.6 visits per month to twice a day. The duration of the interventions varied from two consecutive days to approximately 1.5 years, and the period of the follow-up varied from immediately post-intervention to 1 year after the completion of the intervention (Table 2).

Measurements and Outcomes

The measurements and outcome of the interventions are summarized in Table 2, and effect sizes for the primary and secondary outcomes were presents in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The presentation of the following results will be in the sequence of outcome measurements, significant findings, and examples of successful interventions.

Self-Stigma

HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma was the primary outcome of this review. Various measurements were used to assess self-stigma. Most studies adopted or selected items from existing instruments, and the instruments showed evidence of reliability and validity (n = 21). Berger HIV stigma scale was the most commonly used measurements and was used in six studies [50, 52, 54, 65,66,67].

The results from the 23 intervention studies were inconsistent. Fifteen studies reported positive effect in reducing self-stigma in participants, seven did not achieve significant improvement, and one study actually reported an increase of self-stigma (Table 2). Twelve experimental studies (seven RCTs, five non-RCTs) reported that participants in the intervention groups experienced a significant decrease in the self-stigma compared with those in the control group immediately after the completion of the intervention [55, 57, 58, 63, 67] or at the final follow-up [49, 51, 56, 60, 62, 65, 66]. Four experimental studies (two RCTs, two non-RCTs) did not show significant improvement in self-stigma for participants in the intervention than those in the control group [48, 61, 64, 68]. While one support group intervention conducted in South Africa found that the self-stigma level had increased at the approximately 1.5 year follow-up [50]. Of the six one-group pre–post psychoeducation studies, three studies reported a significant decrease in self-stigma in participant at post-test [47, 59] and the 1-year follow up [54]; three studies did not achieve significant improvement in self-stigma at their follow up [46, 52, 53].

The effect sizes for self-stigma were extracted or calculated from 10 studies [52, 55,56,57, 60,61,62, 66,67,68], including one pre–post study [52]. As shown in Table 4, the pre–post effect sizes were small to large (d = (− 0.02) to 4.64) [52, 55, 57, 61, 62, 67, 68], and the long term effect sizes were small to large (d = (− 0.02) to 0.81) at 3–6 months follow-up [52, 56, 60, 66].

Three studies presented large effect sizes from the intervention group when compared to the control group immediately after the completion of the intervention. Of the three studies, one non-RCT study reported that family members of PLWHA who had received eight weekly 90-min psycho-educational and task-centered group intervention had a significant reduction in self-stigma score compared to those in the control group (mean = 6.00 vs. 8.80, p < 0.001), and resulted in a large effect size (d = 1.10) [62]. However, this type of intervention failed to replicate the positive effects among PLWHA and their partners in another two studies [48, 61].

One support group intervention for treatment adherence delivered by the trained health lay-women demonstrated promising effects related to the reduction in self-stigma [57]. It demonstrated a large effect size (d = 4.64), indicated that PLWHA in the intervention group reported less self-stigma than controls after 6-month intervention (mean = 1.11 vs. 3.43, p < 0.001). The RCT of cognitive behavioral therapy targeted HIV-positive women in South Africa had some positive effects on HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma (d = 2.01) [55]. In comparison to the control group, the intervention significantly lowered the internalized stigma [mean difference = (− 15.10) vs. (− 6.10), p < 0.05]. It is worth noting that there were only 20 participants in the study (intervention group: n = 10, control group: n = 10), and the results should be interpreted with caution.

Two studies had a long-term effect (≥ 3 month) on the self-stigma of HIV-positive women. One RCT conducted in the US tested the effectiveness of a weekly 45-min narrative video of the voices of HIV-positive women [60]. The results showed a treatment-by-time effect in decreasing HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma at 4 and 12 weeks follow-up and achieved a large effect size about reducing overall stigma (d = 0.81) at 3-month follow-up. Another HIV self-care symptom management intervention was also successful regarding the self-stigma outcome among low-income African American mothers in South Africa. Nurses used three modules to deliver HIV-related information, self-care strategies, and mental health problems during their home visits and offered emotional support through follow-up telephone contacts [56]. Comparing the intervention and control groups, the result showed a statistically significant reduction in the self-stigma in the intervention group (mean = 1.49 vs. 1.74, p < 0.001) and achieved a large effect size (d = 0.80) at 6-month follow-up.

Secondary Outcomes

PLWHA’s other aspects of psychological well-being were measured and reported, including depression, self-efficacy, self-esteem, anxiety and stress.

Depression

The most frequently measured secondary outcome was depression, which was assessed in nine studies. The most widely used measurement was the Beck depression inventory (BDI) [48, 55, 61, 62, 66], followed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES-D) [52, 56, 57]. Of the nine studies, five experimental studies (two RCTs, three non-RCTs) observed a significant improvement in depression score among participants in the interventions group than those in the control group [48, 54,55,56, 61, 62], two experimental studies (one RCT, one non-RCT) reported that no significant difference between the two groups [67, 68]. The other two were pre–post comparison studies, with one achieved significant improvement in depression after the intervention [54], and the other demonstrated small effect without significance [52, 54]. As shown in Table 5, the pre–post effect sizes were small to large (d = 0.20–2.40) [52, 55, 61, 62, 67], and the long-term effect sizes were small (d = 0.12–0.15) [52, 54, 56].

The effectiveness of psycho-educational group intervention on depression was evaluated in three studies [48, 61, 62]. One study showed that participants in the intervention group had lower depression score than those in the control group at post-intervention (all p < 0.05). The other two pre–post intervention studies reported an improvement in depression with effect size of 2.40 [62] and 0.30 respectively [61].

It has been reported from the RCT of cognitive behavioral therapy study that participants in the intervention group experienced a significant decrease in depression score compared to those in the control group after the intervention [mean difference = (− 19.20) vs. (− 0.60), p < 0.001], with a large effect size (d = 1.48) [55].

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured in five intervention studies with various outcome measurements [47, 52, 59, 60, 67]. Three studies demonstrated significant improvement in self-efficacy after intervention [59, 67] and 12 weeks after the completion of the intervention [60]. One study found no significant change after intervention [47]. Another study reported the effect size but without reporting the significant levels [52]. As shown in Table 5, the pre–post short term effect sizes were small to large (d = 0.12–0.86) [52, 67], and the long-term effect sizes were small (d = (− 0.02) to 0.22) [52, 60].

Evaluation of a 12-session group-based behavioral intervention among youth (16–24 years) newly diagnosed with HIV yield a small improvement in self-efficacy related to disclosure of HIV status after intervention (d = 0.12) and at 3-month follow-up (d = 0.06) [52]. Gender-specific analysis showed that the intervention improved self-efficacy for discussion on sexual issues among women at post intervention and three-mother follow-up (d = 0.53 and 0.15), while a little decrease at the 3-month follow-up for men [d = 0.25 and d = (− 0.17)]. Another community-based supportive intervention for treatment adherence by healthcare workers found significant improvement in self-efficacy in the intervention group, in compare to the control group after intervention (mean difference = 25.40 vs. 10.70, p < 0.01) [67], with large effect size (d = 0.86).

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in four studies [47, 52, 55, 60]. Three studies have yielded statistically significant results [47, 55, 60], and two of them showed medium to large effect sizes: one narrative intervention reported medium effect size at 12-week follow-up (d = 0.47) [60], another cognitive behavioral therapy reported a large effect size at post-intervention (d = 1.14) [55]. Apart from the three studies, one pre–post group-based behavioral intervention did not report improvement in self-esteem as measured at post-intervention and 3-month follow-up (d = (− 0.07) and (− 0.09)) [52].

Anxiety and Stress

Anxiety and stress were measured in four studies. Three psycho-educational group interventions measured anxiety and stress with the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) and the impact of events scale (IES) [48, 61, 62]. The results of these studies offered encouraging but inconclusive evidence of effectiveness. Two studies showed a significant difference in anxiety and stress between the participants in the intervention and control group after completion of the intervention [48, 62], and one of them showed substantial effects (anxiety: d = 2.10, stress: d = 2.02) [62]. The third psycho-educational group intervention reported a small effect sizes in anxiety and stress of the family members of PLWHAs (d = 0.43 and 0.08, respectively), while no significant difference was found in participants’ pre–post scores [61]. Another self-care symptom management intervention measured the anxiety and stress with the profile of mood states (POMSs), achieved significant but small effect size at 1-month follow up after the completion of the intervention (d = 0.09) [56].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to examine the effectiveness of interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma among PLWHA and their family members. Although there is no restriction on the year of publication, almost all the studies were published since 2000. The increasing number of publications evidenced growing attention to the psychological health of the PLWHA and interventions to reduce their self-stigma over time. The review has identified a variety of interventions, mainly psychoeducational. These interventions have yielded mixed results. The effect sizes ranged from small to large for the self-stigma in the short-term and long-term follow-up, and the effect size ranged from small to large for the secondary outcomes at post-intervention, and small at 3–6 months follow-up. The results suggested a trend to promising effectiveness for some PLWHA and their families. The common interventions demonstrating positive trends to reduce self-stigma and recommendation for future studies are discussed below.

Intervention Approaches and Contents

The review identified five types of interventions: psycho-educational intervention, supportive intervention for treatment adherence (ART), psychotherapy intervention, narrative intervention, and community participation intervention. The heterogeneity of the study, coupled with insufficient data for the measurement of effect size, constrained our ability to draw conclusions on the most effective interventions. We examined the study characteristics and noticed that four studies with large effect sizes focused exclusively on HIV-positive women above 18 years old [55,56,57, 60]. Therefore, the effectiveness of these interventions may not be generalized to men or children.

Similar to self-stigma reduction interventions on other stigmatized conditions [69, 70], the psycho-educational intervention was the predominant approach to reducing HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma, with the perhaps the most popular being those interventions that combined education, skills building, and social support. The educational information that was provided included three main elements: the medical aspects of HIV/AIDS, managing negative feelings and coping with stigma, and building support networks. While it is worth noting that an education-only approach was also effective in reducing HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma [54, 58, 64, 65].

It is encouraging that the empowerment approach in interventions has improved both self-stigma and the psychological well-being of people with people with HIV [51, 55, 60]. These studies empowered PLWHA through the sharing of experience of being an HIV-positive person, their uncomfortable situations and struggles, building up their ability in social and community areas, supporting their family and social relationships, and providing information on stigma and human rights issues. Empowerment is an essential in establishing positive self-image and resilience against the impact of HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has called to promote human rights and empower PLWHA in responding to stigma in the past few years [71]. It is concluded that future studies are to empower PLWHA and their families with similar approaches.

Attrition Rate

Retention of study participants is essential to the success of the intervention. The attrition rate of these interventions ranged from 0.0 to 64.7% in included studies, and five of them reached 29.6% or above, the high attrition rate warrants attention. As the participants may have dropped out due to a flagging motivation to participate, the feasibility, applicability, and acceptability of an intervention should be considered in future studies. Also, the PLWHA are a population hard-to-reach, fear of social stigma and concerns about the possibility of breaching of confidentiality might influence their willingness to participate or continue participation in the study. Strategies, such as creating a friendly-environment, establishing a rapport between the researcher and the participants, acknowledge the sensitive nature of the research topic before enrolment, and providing incentives may help to improve the recruitment and attrition rate among PLWHA [72, 73].

Format of Delivery

Most of the included studies were delivered in a conventional face-to-face group format. The advantages of this approach are that it allows for the sharing of emotions and experiences, increases peer/social support, and reduces social isolation among PLWHA. Also, the literature suggests that using low-cost technology (i.e., radio, telephone, video) is possible to disseminate interventions to stigmatized populations and those living in remote areas. Furthermore, such an approach may encourage participation, since the participants would be assured of greater privacy and confidentiality than might be possible with other approaches.

Unintended Negative Consequences of the Interventions

When conducting stigma-reduction interventions, particular attention should be paid to unintended negative consequences. Although shifting the task of antiretroviral delivery from healthcare professionals to informal community health workers has been recognized as an effective way of delivering quality care, especially in human resources challenged areas [74], one of the support interventions targeting ART adherence that was included in this review showed that peer adherence support increased the perceived stigma among PLWHA [50]. The fear of disclosure and feelings of shame that were expressed by the participants in that intervention could in part be attributed to the unfavorable outcome of that intervention. Thus, supportive programs at the community level should be sensitive to the consequences of the disclosure of identity.

Self-Stigma Reduction Interventions Among Family Members of PLWHA

The evidence suggests that there is a lack of interventional research targeting family members of PLWHA. Only four interventions were implemented in reducing the HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma of family members, through either a dyadic approach or a single-target approach. Two family-based psychosocial interventions that involved family members–child dyads demonstrated positive effects [54, 64], while the two psycho-educational and task-centered group interventions targeting family members only showed mixed results [61, 62], and one showed no improvement in HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma [61]. It is uncertain whether interventions targeting family member–child dyads would be more effective than interventions targeting family members only. A recent systematic review that compared these two approaches with regard to late-life depression tentatively concluded that a dyadic approach might be more beneficial than a single-target (i.e., patient only) approach since the former promotes supportive behaviors from family members [75]. In our review, the positive effects of dyadic approaches might be explained by improved family members support and family members–child communication. The effect of the two approaches (individual versus patient–caregiver dyads) on reducing HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma among family members might be an interesting area for future exploration.

Recommendations for Future Research

This review identified two limitations in current studies on HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma reduction interventions, namely, the poor quality of the methodology, and the lack of qualitative evaluations of the intervention.

First, despite the trend toward greater interest in the reduction of HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma over the past three decades, this systematic review identified a relatively small number of interventions that focused on reducing HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma as compared to interventions targeting HIV/AIDS-related public stigma. Attention should be given to the results of the methodological quality assessment of the included studies. Over one third (10 of 23) of the studies were either pilot studies or studies involved a small sample size (< 30 participants), and over half (13 of 23) of the studies were quasi-experimental studies with or without a control group, which constrained the generalizability of the results. Future studies involving an RCT with a larger sample size could be helpful in determining the effectiveness of an HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma reduction intervention.

Second, to expand our understanding of how best to deliver the intervention, it is crucial to include the voices of the participants in the evaluation of the intervention. A qualitative approach, such as one involving individual or group interviews, or focus groups, could be essential to elicit the participants’ experiences with the intervention and their perceptions of it, and provide insights into the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention, and how to further improve it. It is unfortunate that only two of the studies included in the review adopted a mixed-methods study design and collected feedback from the participants. This highlights the potential to add a qualitative element to studies to give voice to the participants. Future studies with a mixed-methods design are needed to develop and evaluate the intervention.

Limitations of the Review

There are several limitations in this review. Firstly, women were over-represented in self-stigma reduction interventions: over one third (8 of 23) of the included studies only recruited women, future studies may benefit by considering other subgroups of PLWHA, such as men, young children, and older people. Secondly, there was a great deal of heterogeneity in the studies that were included in this review, including in the types of intervention, participants, intensity of the interventions, length of the follow-ups, outcome measurements, the inconsistency of the results, and varied quality of the studies, which made it difficult to compare the results of the interventions; thus, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis. Thirdly, insufficient data precluded the calculation of effect size in some studies. In addition, for studies with small sample size (< 30), the effect size may be influenced by the sampling error (i.e., by chance). Therefore, caution must be taken when interpreting the effect sizes of small size studies [76, 77].

Conclusion

This review identified five types of interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma among PLWHA and their families. Psychoeducation is the most common approach, while other approaches, such as support intervention targeting ART adherence, psychotherapy, narrative intervention, and community participation intervention were less frequently adopted and replicated in the area of HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma reduction intervention. The review suggested a trend to promising effectiveness for some PLWHA and their family members. However, stigma reduction interventions among families of PLWHA are lacking, and more research on interventions targeting family members/caregivers of PLWHA are needed. Overall, the review was constrained by the weakness of the methodological quality and the lack of qualitative evaluations of the intervention. Mixed-methods studies combining an RCT with a larger sample size with qualitative research that includes the voices of the participants will be critical in determining the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS-related self-stigma reduction interventions in the future.

References

Erving G. In: Jenkins JH, Carpenter E, editors. Stigma: notes on a spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1963.

Mathiti V. Street life and the construction of social problems. In: Ratele K, Duncan N, editors. Social psychology: identities and relationships. Cape Town: UTC Press; 2003. p. 336–52.

Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–21.

Drew N, Funk M, Tang S, Lamichhane J, Chávez E, Katontoka S, et al. Human rights violations of people with mental and psychosocial disabilities: an unresolved global crisis. Lancet. 2011;378(9803):1664–75.

Feldman DB, Crandall CS. Dimensions of mental illness stigma: what about mental illness causes social rejection? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(2):137–54.

Ehrenkranz N, Rubini J, Gunn R, Horsburgh C, Collins T, Hasiba U, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among persons with hemophilia A. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31(2):365–7.

Masoudnia E. Public perceptions about HIV/AIDS and discriminatory attitudes toward people living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Iran. SAHARA J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2015;12(1):116–22.

Jin H, Earnshaw VA, Wickersham JA, Kamarulzaman A, Desai MM, John J, et al. An assessment of health-care students’ attitudes toward patients with or at high risk for HIV: implications for education and cultural competency. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1223–8.

Chen J, Choe M, Chen S, Zhang S. The effects of individual- and community-level knowledge, beliefs, and fear on stigmatization of people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):666–73.

Sudha R, Vijay D, Lakshmi V. Awareness, attitudes, and beliefs of the general public towards HIV/AIDS in Hyderabad, a capital city from South India. Indian J Med Sci. 2005;59(7):307.

Houtsonen J, Kylmä J, Korhonen T, Välimäki M, Suominen T. University students’ perception of people living with HIV/AIDS: discomfort, fear, knowledge and a willingness to care. Coll Stud J. 2014;48(3):534–47.

Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160.

Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, Stewart A, Phetlhu R, Dlamini PS, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(6):541–51.

Mhode M, Nyamhanga T. Experiences and impact of stigma and discrimination among people on antiretroviral therapy in Dar es Salaam: a qualitative perspective. AIDS Res Treat. 2016;2016:1–12.

Liu Y, Canada K, Shi K, Corrigan P. HIV-related stigma acting as predictors of unemployment of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2012;24(1):129–35.

Dlamini PS, Kohi TW, Uys LR, Phetlhu RD, Chirwa ML, Naidoo JR, et al. Verbal and physical abuse and neglect as manifestations of HIV/AIDS stigma in five African countries. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(5):389–99.

Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):781–90.

Nyblade LC. Measuring HIV stigma: existing knowledge and gaps. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):335–45.

Van Brakel WH. Measuring health-related stigma—a literature review. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):307–34.

Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2528–39.

Musheke M, Ntalasha H, Gari S, Mckenzie O, Bond V, Martin-Hilber A, et al. A systematic review of qualitative findings on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):220.

Darlington CK, Hutson SP. Understanding HIV-related stigma among women in the Southern United States: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):12–26.

Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Chambers L, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011453.

Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18640.

Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2002;6(4):309–19.

Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1823–31.

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, Browning WR, Raper JL, Mugavero MJ, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):283–91.

SeyedAlinaghi S, Paydary K, Kazerooni PA, Hosseini M, Sedaghat A, Emamzadeh-Fard S, et al. Evaluation of stigma index among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in six cities in Iran. Thrita. 2013;2(4):69–75.

Ogunmefun C, Gilbert L, Schatz E. Older female caregivers and HIV/AIDS-related secondary stigma in rural South Africa. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2011;26(1):85–102.

Saengtienchai C, Knodel J. Parental caregiving to adult children with AIDS: a qualitative analysis of circumstances and consequences in Thailand. PSC research report; 2001.

Wight RG, Aneshensel CS, Murphy DA, Miller-Martinez D, Beals KP. Perceived HIV stigma in AIDS caregiving dyads. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(2):444–56.

Wight RG, Beals K, Miller-Martinez D, Murphy D, Aneshensel C. HIV-related traumatic stress symptoms in AIDS caregiving family dyads. AIDS Care. 2007;19(7):901–9.

Demmer C. Experiences of families caring for an HIV-infected child in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: an exploratory study. AIDS Care. 2011;23(7):873–9.

Grossman CI, Stangl AL. Global action to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18881.

Haghdoost A, Karamouzian M. Zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination, and zero AIDS-related deaths: feasible goals or ambitious visions on the occasion of the world AIDS day? Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(12):819.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS Strategy 2016–2021; 2016.

Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):49–69.

Sengupta S, Banks B, Jonas D, Miles MS, Smith GC. HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1075–87.

Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18734.

Mak WW, Mo PK, Ma GY, Lam MY. Meta-analysis and systematic review of studies on the effectiveness of HIV stigma reduction programs. Soc Sci Med. 2017;188:30–40.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

O’Connor SR, Tully MA, Ryan B, Bradley JM, Baxter GD, McDonough SM. Failure of a numerical quality assessment scale to identify potential risk of bias in a systematic review: a comparison study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):224.

Morris SB. Estimating effect sizes from pretest–posttest-control group designs. Organ Res Methods. 2008;11(2):364–86.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1988.

Skinta MD, Lezama M, Wells G, Dilley JW. Acceptance and compassion-based group therapy to reduce HIV stigma. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(4):481–90.

Uys L, Chirwa M, Kohi T, Greeff M, Naidoo J, Makoae L, et al. Evaluation of a health setting-based stigma intervention in five African countries. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(12):1059–66.

Pomeroy EC, Rubin A, Laningham VL, Walker RJ. “Straight Talk”: the effectiveness of a psychoeducational group intervention for heterosexuals with HIV/AIDS. Res Soc Work Pract. 1997;7(2):149–64.

Abel E. Women with HIV and stigma. Fam Community Health J Health Promot Maint. 2007;30(1, Suppl):S104–6.

Masquillier C, Wouters E, Mortelmans D, Roux Booysen F. The impact of community support initiatives on the stigma experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):214–26.

Bhatta DN, Liabsuetrakul T. Efficacy of a social self-value empowerment intervention to improve quality of life of HIV infected people receiving antiretroviral treatment in Nepal: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1620–31.

Hosek SG, Lemos D, Harper GW, Telander K. Evaluating the acceptability and feasibility of Project ACCEPT: an intervention for youth newly diagnosed with HIV. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(2):128–44.

Rao D, Desmond M, Andrasik M, Rasberry T, Lambert N, Cohn S, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and initial efficacy of the ‘Unity workshop’: an internalized stigma reduction intervention for African American women living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:172.

Smith Fawzi MC, Eustache E, Oswald C, Louis E, Surkan PJ, Scanlan F, et al. Psychosocial support intervention for HIV-affected families in Haiti: implications for programs and policies for orphans and vulnerable children. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1494–503.

Tshabalala J, Visser M. Developing a cognitive behavioural therapy model to assist women to deal with HIV and stigma. S Afr J Psychol. 2011;41(1):17–28.

Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Eron J, Black BP, Pedersen C, Harris DA. An HIV self-care symptom management intervention for African American mothers. Nurs Res. 2003;52(6):350–60.

Nyamathi A, Ekstrand M, Salem BE, Sinha S, Ganguly KK, Leake B. Impact of Asha intervention on stigma among rural Indian women with AIDS. West J Nurs Res. 2013;35(7):867–83.

Nambiar D, Ramakrishnan V, Kumar P, Varma R, Balaji N, Rajendran J, et al. Knowledge, stigma, and behavioral outcomes among antiretroviral therapy patients exposed to Nalamdana’s radio and theater program in Tamil Nadu, India. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(4):351–66.

Rounds KA, Galinsky MJ, Despard MR. Evaluation of telephone support groups for persons with HIV disease. Res Soc Work Pract. 1995;5(4):442–59.

Barroso J, Relf MV, Williams MS, Arscott J, Moore ED, Caiola C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy of a stigma reduction intervention for HIV-infected women in the Deep South. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(9):489–98.

Gordon VL. Effectiveness of a time-limited psychoeducational group for cohabitating sero-negative partners and spouses of persons with HIV disease (immune deficiency). 1998.

Pomeroy EC, Rubin A, Walker RJ. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational and task-centered group intervention for family members of people with AIDS. Soc Work Res. 1995;19(3):142–52.

Apinundecha C, Laohasiriwong W, Cameron MP, Lim S. A community participation intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, northeast Thailand. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1157–65.

Bhana A, Mellins CA, Petersen I, Alicea S, Myeza N, Holst H, et al. The VUKA family program: piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):1–11.

Echenique M, Illa L, Saint-Jean G, Avellaneda VB, Sanchez-Martinez M, Eisdorfer C. Impact of a secondary prevention intervention among HIV-positive older women. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):443–6.

Kaai S, Bullock S, Sarna A, Chersich M, Luchters S, Geibel S, et al. Perceived stigma among patients receiving antiretroviral treatment: a prospective randomised trial comparing an m-DOT strategy with standard-of-care in Kenya. SAHARA J J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2010;7(2):62–70.

Muñoz M, Finnegan K, Zeladita J, Caldas A, Sanchez E, Callacna M, et al. Community-based DOT-HAART accompaniment in an urban resource-poor setting. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):721–30.

Abel E, Rew L, Gortner EM, Delville CL. Cognitive reorganization and stigmatization among persons with HIV. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(5):510–25.

Mittal D, Sullivan G, Chekuri L, Allee E, Corrigan PW. Empirical studies of self-stigma reduction strategies: a critical review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):974–81.

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(1):39–50.

UNAIDS. Development of a tool to measure stigma and discrimination experienced by people living with HIV 2008.

Loutfy MR, Logan Kennedy V, Mohammed S, Wu W, Muchenje M, Masinde K, et al. Recruitment of HIV-positive women in research: discussing barriers, facilitators, and research personnel’s knowledge. Open AIDS J. 2014;8:58.

Zweben A, Fucito LM, O’Malley SS. Effective strategies for maintaining research participation in clinical trials. Drug Inf J. 2009;43(4):459–67.

Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8(1):8.

Stahl ST, Rodakowski J, Saghafi EM, Park M, Reynolds CF, Dew MA. Systematic review of dyadic and family-oriented interventions for late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(9):963–73.

Fan X, Konold T. Statistical significance versus effect size. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01368-3.

Hattie J. Visible learning for teachers: maximizing impact on learning. London: Routledge; 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, P.H.X., Chan, Z.C.Y. & Loke, A.Y. Self-Stigma Reduction Interventions for People Living with HIV/AIDS and Their Families: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav 23, 707–741 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2304-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2304-1