Abstract

Although it is the most widely accepted form of organic guarantee, third party certification can be inaccessible for small-scale producers and promotes a highly market-oriented vision of organics. By contrast, participatory guarantee systems (PGS) are based on principles of relationship-building, mutual learning, trust, context-specificity, local control, diversity, and collective action. This paper uses the case study of the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets to explore how PGS can be used to support a more alternative vision of organics, grounded in the notion of food sovereignty. It presents some of the key challenges and opportunities associated with the approach, and highlights its potential to serve as a locally-based institution for collective action, thereby offering some structural support to alternative agri-food initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The idea of providing consumers of organic products with some form of guarantee that what they are consuming is truly organic dates back to the early days of the organic movement.Footnote 1 Until the 1990s, these guarantee systems tended to be self-regulatory, voluntary, and based on a process of peer review (Seppänen and Helenius 2004; González and Nigh 2005). However, as the organic sector increased in scale, there has been a shift toward a third party model, in which standards and verification procedures are determined by independent agencies, certifications are carried out by professional inspectors and extension assistance is divorced from certification (González and Nigh 2005; Mutersbaugh 2005). The main benefits of this third party certification framework are that it offers a high degree of accountability and objectivity, and conforms to standards set by national governments and organizations such as the International Standards Organization (ISO), thereby granting producers access to the potentially lucrative niche organic market.

While it serves a number of clear functions, third party certification is also subject to critique on a number of fronts (see Tovey 1997; Gómez Tovar et al. 1999; Allen and Kovach 2000; Raynolds 2000; Kaltoft 2001; Rigby and Bown 2003; González and Nigh 2005; Mutersbaugh 2005; Böstrom and Klintman 2006). Offering a summary, Nelson et al. (2010, p. 227) note that it has been criticized “for promoting an input substitution model of organic agriculture, for being removed from the grassroots level, and for its inaccessibility to many small-scale producers”. In response to these issues, a number of alternatives have emerged, including: cooperativization and internal control systems, which reduce the bureaucratic and cost barriers to third party certification; alternative labeling strategies, which allow producers and consumers to create their own locally-based definition of sustainable production; and, participatory guarantee systems (PGS), which represent the most widely recognized alternative certification system for organic products.

This article presents a case study of a network of local organic farmers’ markets in Mexico (the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets), and uses it to explore the role that PGS can play within the organic movement. Specifically, we address the question of whether—and to what extent—PGS is able to serve as an innovative governance mechanism to support the development of an organic sector that is grounded in the principles of food sovereignty, and that challenges the more conventionalized, market-driven, export-oriented organic model.

In order to answer this question, we draw on the growing body of literature regarding food sovereignty, including discussion of the concept’s key principles, and how a variety of actors around the world are using those principles as a conceptual framework to facilitate the construction of alternative food system initiatives (see Desmarais 2007; Pimbert 2008; Patel 2009; Wittman et al. 2010; Altieri et al. 2012; Anderson and Bellows 2012). We also use Ostrom’s (1990) notion of locally-based institutions for collective action to support our analysis, and suggest that PGS has the potential to serve as such an institution, providing valuable structural support for efforts to challenge the conventional food paradigm.

Situating the results of our research on PGS in Mexico within these bodies of literature allows us to frame our discussion of how that country’s organic sector is being re-imagined within broader narratives regarding a global re-imagining of food system structures. Such framing is timely, as adoption of PGS has increased rapidly over the last decade; however, although a number of case studies have documented its implementation (see IFOAM 2008, 2013; Källander 2008; Meirelles 2010), to date there has been very little examination of the subject within the academic literature (for exceptions see Zanasi et al. 2009 and Nelson et al. 2010).

We begin by providing a brief overview of PGS, including its key underlying principles, global relevance, and relationship to the notions of food sovereignty and institutions for collective action. The Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets is then introduced, and the way in which PGS is being practiced in Mexico is presented. The article then turns to an analysis of some of the challenges inherent in translating a framework that, in many respects, represents a philosophical ideal, into a practical, functioning reality. This analysis focuses on three themes. Firstly, we examine the need for the PGS movement to strike a delicate balance between maintaining space for local control and flexibility, and creating the degree of standardization necessary to ease functioning and assure legislative recognition. Secondly, we consider the issue of trust, and assess some of the benefits and limitations of trying to engage in a trust-based system. Finally, we outline the gap between the participatory ideal of PGS and the levels of active participation that are actually being achieved. Overall we argue that, in spite of a number of challenges and limitations that must still be addressed, the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets has been able to use PGS as an institution for collective action that supports its efforts to re-imagine Mexico’s organic sector, from one that is almost exclusively dominated by the production and export of a small number of high value crops, to one that is inclusive of a more diverse range of products and people and, over the long term, has the potential to help the country move toward greater levels of food sovereignty.

Participatory guarantee systems

In its 2008 report on PGS, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) notes that “[t]he very lifeblood of these programs lies in the fact that they are created by the very farmers and consumers that they serve. As such, they are adapted and specific to the individual communities, geographies, politics and markets of their origin”. Although this makes developing a concise definition challenging, in 2008 the IFOAM-based International PGS Task Force agreed that PGS could generally be defined as “locally focused quality assurance systems [that] certify producers based on active participation of stakeholders and are built on a foundation of trust, social networks and knowledge exchange” (IFOAM 2008). They also “tend to address not only the quality assurance of the product, but are linked to alternative marketing approaches (home deliveries, community supported agriculture groups, farmers’ markets, popular fairs) and help to educate consumers about products grown or processed with organic methods” (Källander 2008, p. 1).

The first international workshop on PGS was held in Brazil in 2004, with representatives from initiatives in Argentina, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, India, Japan, Lebanon, Mexico, New Zealand, Palestine, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, Thailand, the United States, Uganda and Uruguay. By 2014, IFOAM was hosting an international task force devoted to promoting PGS, and its PGS database contained records for over 20,000 certified producers from initiatives in 34 countries.Footnote 2 The most prominent leader in the PGS movement to date has been Brazil, where the Ecovida network of ecological producers has certified over 3000 producers in the Southernmost part of the country, and has managed to create a nationally recognized seal for PGS certified products (see Zanasi et al. 2009). In addition to the significant support received from NGOs and producer associations such as Ecovida, PGS also has the important backing of IFOAM and has been included in legislation governing the organic sectors of a number of countries, including Bolivia, Brazil and Mexico.

At a practical level, PGS seeks to make organic certification more accessible to small-scale producers, particularly (though not exclusively) in the Global South. This focus is important given that approximately 80 % of the world’s organic producers are located in countries that receive official development assistance from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (Willer and Lernoud 2014). More broadly, PGS also attempts to challenge some of the ideological assumptions that underlie the third party certification perspective—for example, the prioritization of export-oriented production, the notion that organic agriculture can be measured primarily in terms of prohibited and allowed inputs, and the idea that only formally trained experts can be trusted to make valid determinations of certification status.

PGS, food sovereignty and locally-based institutions for collective action

Coined in 1996 by the global peasant organization Via Campesina, food sovereignty can be defined as “the right of each nation to maintain and develop its own capacity to produce its basic foods, respecting cultural and productive diversity…the right to produce our own food in our own territory…[and] the right of peoples to define their agricultural and food policy” (Desmarais 2007, p. 34). As a concept, food sovereignty bears much in common with PGS. For example, although it is now widely employed around the world, it has strong roots in the Global South, and a substantial focus on the empowerment of resource-poor, small-scale producers (Desmarais 2007; Pimbert 2008). Similarly, it is closely linked to notions of sustainable agriculture that extend beyond an input-substitution model to include broader definitions of ecological—as well as social—sustainability (Altieri et al. 2012). The food sovereignty framework also favors diversity and context-specificity over homogeneity and uniformity, and envisions people primarily as citizens rather than consumers, and food primarily as a source of nourishment rather than a commodity (Pimbert 2008; Patel 2009). As such, it is inherently political, and strives to engender deep, systemic changes to dominant political and economic structures (Patel 2009; Wittman et al. 2010; Anderson and Bellows 2012).

In considering whether and how PGS may contribute to the kind of transformative change envisioned by the food sovereignty movement, Ostrom’s (1990) concept of locally-grounded institutions for collective action serves as a useful analytical tool. Such institutions “can influence behavior directly by establishing mechanisms of rewards and punishments or indirectly to help individuals govern themselves by providing information, technical advice, alternative conflict-resolution mechanisms, and so forth” (Ostrom and Ahn 2008, p. 24–25).Footnote 3 Ostrom’s work is particularly relevant to a discussion of PGS because, among other things, it highlights the importance of participatory decision-making regarding regulations and their implementation, adaptation of regulatory systems to local conditions and recognition of grassroots-based governance systems by higher level authorities (Ostrom 1990), as well as the construction and maintenance of strong relationships of trust (Poteete et al. 2010).

Because the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets, and many of its individual member markets along with participants in those markets, consciously employ food sovereignty discourse in describing their work, the concept is particularly appropriate to the case study we are presenting. Although those same people do not explicitly adopt the language of institutions for collective action in relation to their work on PGS, we argue that the development and implementation of these alternative guarantee systems represents an important innovation in food system governance that lends itself well to analysis through this lens.

Methods

The information presented in this paper is based on an in-depth case study of the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets that was carried out between October, 2008 and November, 2009. At the time of data collection, the network consisted of 13 fully functioning markets and an additional eight market initiatives in various stages of development. Of the 13 markets, ten were chosen as research sites. These markets were located in the states of Mexico (Chapingo and Metepec), Puebla (Puebla), Tlaxcala (Tlaxcala), Veracruz (Xalapa, Coatepec, and Xico), Oaxaca (two markets in Oaxaca City), and Chiapas (San Cristóbal de las Casas). Markets in Guadalajara (Guadalajara), Baja California Sur (San José del Cabo) and Chiapas (Tapachula) were not included in the study due to travel limitations; however, participants from those markets, as well as many of the market initiatives, were able to participate in the research through discussions at network meetings and other gatherings.

A total of 80 surveys with producers were conducted across the ten participating markets, while 48 consumer surveys were applied in Chapingo, Metepec, and Puebla. The survey data were complemented by information from 41 in-depth semi-structured interviews. Of those, 16 were with local organic market producers, 8 with local organic market consumers, 7 with a variety of key informants (including market and PGS organizers and a representative of the Ministry of Agriculture), and 10 with conventional producers. The study also involved extensive participant observation, including attendance at market meetings and network assemblies, involvement in a local PGS committee, and participation in workshops designed to develop regulations for Mexico’s organic legislation. Although data collection was not focused exclusively on PGS, the subject was a core component of the producer and consumer surveys and interviews, as well as much of the participant observation.

The Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets and PGS in Mexico

The Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets

The primary force behind the development of PGS in Mexico—and the focus of the research presented here—is the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets (referred to hereafter as the Network), a registered civil association based out of Chapingo, Mexico. The Network traces its roots back to 1996, when the country’s first local organic market project began in the city of Guadalajara. 7 years later, in 2003, three additional markets dedicated to the sale of locally produced organic goods were opened in Chapingo, Xalapa, and Oaxaca City, and in 2004 those four markets formed the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets. Since then, the number of participating markets has increased rapidly. As mentioned, at the time of data collection there were 13 fully-functioning markets across 8 states participating in the Network and, by the time of this writing, that number had grown to more than 20 markets across 15 states. Based on 2009 data, almost half of the producers selling goods in these markets had household earnings of less than 5000 pesos/month (falling below the average base salary for a Mexican worker) and 76 % farmed on 5 hectares of land or less. Notably, 49 % had some form of university education, which is a stark contrast to 2007 agricultural census data showing that just 4 % of the country’s producers had completed 1 year or more of post-secondary education (INEGI 2011).

Although each of the participating markets has its own particular vision, a useful general description is provided by Escalona (2009, pp. 227–228). Based on an in-depth study of six of the Network’s markets, he suggests that each serves as:

a place (micro-space) where direct contact between producers and consumers is promoted. It is a public space, accessible to all, in which the producers offer foods that they themselves have produced using clean (ecological) techniques, or techniques that are in transition toward that [organic] ideal. In addition, it is a space where consumers can find high quality food items, and learn the stories behind their production. In this way, a face is put on the food that consumers take to their homes, and this allows for a revalorization of that food and the work implied in its production. In many cases, the market is also a space for education and reflection about food consumption, and for the facilitation of interpersonal relationships that are closer, more human, and built on more solidarity, than is typical in a market setting.

PGS as practiced in Mexico

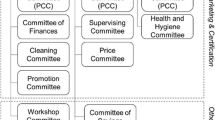

Just as its deeply context-specific nature makes PGS somewhat challenging to define as a general concept, it also makes it difficult to define its practice on a national scale. That said, although there are nuances to the specific ways in which PGS is applied in local organic markets across Mexico, it is possible to provide a high level outline of how the system functions. At a local level, PGS in Mexico is managed by certification committees based out of the Network’s member markets. These committees include a combination of producers, consumers and other key stakeholders (e.g. agronomists, third party organic inspectors, students) who volunteer their time to collectively carry out PGS.

The process essentially involves six steps: (1) a producer interested in being certified requests an application and submits it to the committee; (2) the committee reviews the application and, if no obvious barriers to certification are apparent, schedules a site visit; (3) members of the committee visit the production site; (4) the committee meets to review the case using Mexico’s national organic standard as a principle guide for determining certification status; (5) the committee informs the producer of its decision (either certification with no conditions, certification with conditions, or no certification); and (6) regardless of the outcome, the committee offers ongoing monitoring and capacity-building in organic production to the producer.Footnote 4

Although the exact structure and functioning of the certification committees is largely determined at the local level, capacity-building and support are provided by the Network. For example, it offers national courses and workshops to train local PGS committee coordinators, provides resource materials such as PGS implementation handbooks, guides designed to make the national organic standards easier to understand and PGS case studies, and supports research on PGS that aims to facilitate improvements in its functioning. It is important to highlight that, although all producers certified through PGS in Mexico sell their products through the Network’s markets, not all of the Network’s producers have been certified, either through PGS or by a third party agency. More details on this distinction will be provided later in the paper. In addition, a number of PGS certified producers sell their products through channels other than the Network’s markets, with the Network’s reputation for effectively implementing PGS serving as a guarantor for organic authenticity in those venues, which include organic specialty stores and other regionally-based, private distribution systems.

A rationale for adopting PGS in Mexico

The majority of producers participating in the Network markets have not had their production certified as organic by a third party agency. Nevertheless, almost all of those surveyed indicated that they felt having some form of certification system in place to govern the sale of products in a local organic market was highly important as a means of maintaining market integrity and consumer confidence. When asked to rate this importance on a scale of 1–7, the average response was 6.6. Local organic market consumers reported similar feelings, with 88 % of those surveyed feeling that it was important for the markets to have some form of organic certification system in place as a complement to the trust built between producer and consumer.

While producer and consumer desires for some kind of certification mechanism within the Network markets are certainly important, the issue of actively implementing certification systems became considerably more pressing following the 2006 adoption of a national law governing the organic sector that requires producers to be certified—either by an accredited third party agency or through a recognized PGS—in order to refer to their production as “organic”. With its holistic interpretation of organic agriculture, which includes a focus on local production-consumption networks, social justice, and community building, PGS is widely considered to be more consistent with the Network’s food sovereignty oriented approach than third party certification. In addition, its accessibility to the kind of small-scale producers who dominate the Network markets has made it an appealing alternative from a practical perspective, as most cannot afford the cost, or navigate the bureaucracy, of third party certification.

Extent of PGS practice

Although it may be a more accessible and philosophically appropriate option than third party certification, PGS has still not been adopted uniformly across the Network, and there are gaps in its implementation, even within markets where it is being actively practiced. At the time that research was conducted, all ten participating markets were engaged to some extent in PGS, and almost all (89 %) of the producers surveyed were able to explain its basic tenets, mentioning for example the joint participation of producers and consumers in the certification committees, the low costs and minimal bureaucracy involved, the extension work done in conjunction with certification, and the importance of trust as the underlying fixture of the process. A slim majority (60 %) of the producers surveyed reported having achieved organic certification through their market’s PGS.Footnote 5 Almost half (46 %) also spent time volunteering as members of their market’s participatory certification committee, making certification visits to fellow farmers (see Fig. 1). A 2012 report on the state of PGS in Mexico noted that, at that time, 6 of the Network’s markets had fully functioning PGS committees, members of which made regular training visits in an effort to build capacity in the remaining markets (Villanueva and Schwentesius 2012).

Although surveys and interviews with consumers were only conducted in four markets, and the consumer population was much smaller than that of producers, results demonstrate a clear gap between the two groups in terms of awareness of, and participation in, participatory guarantee systems. Whereas 89 % of Network producers were able to readily define participatory certification, only 30 % of consumers could do the same. The majority had never heard of the term, while a small number were familiar with it, but did not know what it meant. Only 27 % reported that PGS contributed to the trust they had in the products available at a Network market, with direct trust in the producers and in the market as a whole acting as more common guarantors of organic quality (see Fig. 2). Finally, only 11 % of the consumers surveyed reported participating in a participatory certification committee (see Fig. 1).

The reach of PGS validity

Article 24 of Mexico’s Organic Products Law explicitly states that “participatory organic certification will be promoted for small-scale producers organized to that effect…[so that their products] can be sold as organic within the national market” (italics added). As such, currently, products certified through a PGS in Mexico can legally be sold as organic anywhere within, but not outside of, the country’s borders. For the vast majority of Network producers, the scale of their operations acts as a natural barrier against export; however, when asked their opinion on the matter, 62 % felt that PGS certification should be considered valid internationally so that sale outside of Mexico could be at least a potential option (see Fig. 3). The most geographically restricted opinion regarding PGS validity—that the certification should only be considered valid within the market where it is carried out—was held by only 9 % of respondents. In most cases, these respondents cited an ideological commitment to prioritizing local markets as the main reason for their opinion.

On the surface, the desire on the part of so many Network producers to use PGS as a platform for expanding market access could be perceived as contrary to the promotion of a food sovereignty-based vision of locally-based production-consumption chains; however, the Via Campesina has made clear that food sovereignty should not be viewed as a complete rejection of non-local trade, but rather as a declaration that such trade must be conducted within a framework not governed by conventional relationships of domination (Patel 2009). Seen through this lens, the use of a grassroots-based alternative to conventional organic certification may be viewed as a concrete example of how actors who have been marginalized by the global market system can potentially enter that very system on their own terms.

Balancing the need for legitimacy with a grassroots, flexible approach

Are PGS operating procedures reliable?

One of the key reasons for considering PGS as an innovative governance structure that can support a shift toward greater food sovereignty is that, unlike third party organic certification, its operating procedures are meant to include a degree of flexibility that allows for locally-based, participatory decision-making. For some research participants, the extent to which PGS decision-making authority was considered flexible and locally-grounded raised some concerns with respect to the legitimacy of the system. The most extreme position—expressed by very few—was summarized by a producer in Oaxaca: “The way [participatory certification] works now, it is too subjective, so I don’t think it’s valid, even if you’re just talking about selling in [one local] market”.Footnote 6 Representing the majority opinion, another Oaxacan producer was less harsh but still critical, suggesting that “[t]he way the concept has been explained to me, I have all the confidence in the world in participatory certification, but the way it is actually working in practice right now, well, we’re just starting, and it isn’t that it doesn’t work, but let’s just say that because we’re just starting I don’t have 100 % trust yet”. The desire to ensure that PGS be practiced in a sufficiently formal manner was also expressed by some consumers. For example, a regular visitor to the local organic market in Puebla noted that “[t]he idea [of PGS] is wonderful, but it’s still a bit open, and I think in order to maintain a certain level of recognition as something that is trustworthy, so that the [Network] markets don’t get burned, it has to be done in a strict way”.

One market coordinator explained how the Network’s efforts to promote PGS and ensure its inclusion within Mexico’s organic legislation, along with his own reading on the subject, helped assuage his concerns about legitimacy: “At first I was against [PGS] because it had no official authorization and didn’t offer the possibility to sell outside of my local market, but those concerns have been addressed now, and also, when I started to read more about the Brazilian experience, the idea became more interesting to me”. Still, he qualified his support, noting that “it will be necessary to have an office, a seal, and all of those things organized. It [PGS] will have to be treated like a business model, not like something romantic”. Many producers agreed that PGS “requires a seal or something to make it official” and that “it has to be professional”. This is in line with case studies of PGS in India, New Zealand, Brazil, the United States and France, which unanimously found a recognizable seal, whether it be an NGO logo or a PGS-specific indicator, to be an important element of a successful initiative (IFOAM 2008).Footnote 7 It is also consistent with Ostrom’s (1990) assessment that, in order to function effectively, locally-grounded institutions for collective action must maintain clear, strict standards governing issues such as who is excluded from a system, how monitoring takes place and how sanctions for non-compliance are applied.

In addition to suggestions that a seal be developed as part of helping PGS gain legitimacy in Mexico, others pointed to the importance of ensuring that ‘professionals’ play a central role in the process. A producer often looked to as a model of agroecological practice explained that he did not feel competent to participate in his market’s PGS committee because of a lack of formal training. “I do trust the participatory certification process” he said, “provided that people from the university, who are trained in how to make a proper determination [regarding certification status] are involved”. This stance is, to an extent, at odds with the PGS philosophy of viewing producers as professionals by virtue of their practical experience; however, it is reflective of pressures to fall into conventional power dynamics and rely on ‘expert’ knowledge that can commonly affect participatory endeavors (see Gaventa 2006; Flora and Flora 2006). The sentiment was expressed by a number of Network producers. In one market, for example, the exit of a professionally-trained organic inspector from the participatory certification committee led to a distinct decrease in the committee’s activity for a period of time, while in another market the committee only made visits provided that volunteer agronomists from a local university were able to attend.

Looking beyond operations in individual markets, the majority of producers expressed a desire for the Network as an organization to act as a kind of authority guaranteeing the legitimacy and reliability of the PGS work carried out by its member markets. The hesitancy to entrust the PGS process to local committees without the overseeing eye of an organization such as the Network is similar to the hesitancy to entrust certification visits to producers without the overseeing eye of a professional agronomist. Both concerns could be construed as being somewhat in conflict with the PGS tenets of trusting producers as professionals and devolving authority to the local level; however, even one of the staunchest promoters of the PGS ideals argued:

One thing we need to do really uniformly is the certification process. We need to be really clear about that, and make sure everyone [in the Network] does it. Which means [the Network] has to send out somebody to do verification. They have to look at the notebooks and do a random selection and go and check people out. As soon as it comes down that that’s going to happen people are going to get their act together.

This perspective is consistent with Ostrom and Ahn’s (2008) assertion that monitoring does play a key role, even within primarily trust-based institutions. It is also echoed in analysis of PGS in Brazil, which found the NGO Rede Ecovida plays an essential role in terms of providing some degree of centralized authority for PGS, thereby helping to guarantee its legitimacy (Zanasi et al. 2009). Studies elsewhere have also pointed to the important role of an organizing NGO or producer association for PGS success, and note that the capacity of this managing organization in terms of staff, funding, expertise and social capital is key (IFOAM 2008). To date, the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets has worked with minimal resources to support PGS in its member markets and at the national level, and it remains to be seen how it will sustain this work on an ongoing and consistent basis in the future.Footnote 8

The implications of legal recognition for PGS

An important factor with respect to both the real and perceived legitimacy of PGS in any context is whether or not it is recognized by law, thereby granting producers the right to legally refer to their products as “organic”. In Mexico, the Network of Local Organic Markets was able to successfully lobby the government to include participatory certification in its 2006 Organic Products Law. This was widely seen as a coup for supporters of non-industrial organics within the country; however, the victory signaled the beginning of a challenging process to develop regulations clear and formal enough to be acceptable to the Ministry of Agriculture, but flexible and inclusive enough to be consistent with the PGS philosophy. These regulations were finally published in October, 2013, and included recognition for PGS certified products provided that they were certified by an organization recognized by the Ministry of Agriculture (Suarez 2014).Footnote 9

The Mexican government’s formal recognition of PGS can be considered reflective of Ostrom’s (1990, p. 212) argument that “regional and national governments can play a positive role in providing facilities to enhance the ability [of those involved in an institution for collective action] to engage in effective institutional design”. Indeed, engaging with government to achieve legislative recognition has been widely recognized as critical to the success of PGS, and working toward this goal is considered a priority at the global level (see IFOAM2008; Källander 2008; Meirelles 2010; Nelson et al. 2010). However, the same people arguing in favor of this legislative recognition acknowledge that there are some inherent challenges when it comes to incorporating PGS into a legal framework in a way that allows it to maintain its core principles. Källander (2008, p. 23) suggests that “there lies an interesting challenge, or even contradiction, in making a participatory guarantee system guide or manual” and poses the question of whether it is even possible to successfully walk the line between “guiding and prescribing” (with the latter being seen in a negative light). Although this observation specifically references the development of non-legislative PGS norms, it is only more relevant when it comes to writing PGS into laws, which by their very nature are even more prescriptive than guides or manuals.

One specific challenge relates to the difficult—if not impossible—nature of translating the more alternative, or radical, elements of the PGS vision into law.Footnote 10 As one Network market organizer explained, “our work implies a different world vision, different values, and we can talk about that here [at a Network meeting], but how are we ever going to be able to get it put into the regulations [for the national organic law]?” Another concurred that “participatory certification is a civil society idea, a social process, and not something that can ever really be put into a law…” These discomforts could be considered reflective of Tovey’s (1997, p. 33) assertion that, when governments seek to institutionalize organic agriculture through the creation of regulatory standards, they necessarily “wrench the production practices free from [the ideological content of the movement] and slot them into a different context in which they do not in fact fit at all easily”.

Others have suggested that the process of trying to institutionalize an organic philosophy inevitably leads to suppression of the broader values put forward by more alternatively-oriented actors within the organic movement, which are seen as threatening to the dominant structures of industrial capitalist society (see Vos 2000; Goodman 2000). Indeed, a number of research participants were fearful about potential co-opting, and thereby conventionalizing, of the Network’s agenda that could result from government involvement. Specifically questioning the state’s ability to deal successfully with PGS one Network leader suggested that “a good idea in the hands of the government is a lost idea”.

If the Network’s more alternative positions on social, ecological and economic justice may be challenging—if not impossible—to incorporate into the relatively narrow scope of the legal framework governing Mexico’s organic sector, perhaps equally challenging were attempts to use a participatory, consensus-based approach to develop national regulations for PGS. Notably, both the Network and the Mexican government made attempts to be inclusive in the drafting of the regulations, which was done through a series of participatory meetings and workshops held over a 2 year period. However, such attempts were fraught with difficulties. One market organizer who participated in the process summarized the issue, noting that “if the four markets [in her region] could not agree on how PGS should be managed, how could we ever expect to reach agreement at the national level”. Indeed, primarily because of how difficult it proved to achieve consensus, the regulatory chapter governing PGS was one of the last sections of the Organic Products Law to be fully drafted. Interestingly, Meirelles (2010) explains that similar difficulties were largely responsible for stalling the development of organic legislation in Brazil in the 1990s.Footnote 11

Could PGS standards be excessive?

While the above discussion focused on operating procedures and legal recognition, the issue of determining PGS organic standards is one more arena where the tensions between maintaining a grassroots approach and achieving legitimacy through increased regulation and standardization manifest themselves. Specifically, Network meetings on the subject of PGS revealed significant debate within and between markets on the issue of how (or if) to consider social and ecological indicators that go beyond the input-substitution model of organics found in most third party agency standards (and Mexico’s national standard). Arguing for the need for PGS to be inclusive, a representative of the Ministry of Agriculture’s Organic Agriculture Working Group suggested that, if it tries to include elements that go beyond the basic organic standards used by certification agencies, “the great challenge of [PGS] will be that it could end up being even stricter than [third party certification] and it could become something very exclusive, more so than inclusive, and it could become something closed off, which is not really the idea”. This potential risk is recognized in a case study of PGS in New Zealand, which found that “overenthusiastic individuals” could sometimes “get carried away with their own ideas of what is organic when they visit a farm”, and in so doing impose excessively strict standards (IFOAM 2008, p. 15). Still, a number of market representatives expressed a strong desire to work with expanded standards that more directly reflected ideals related to food sovereignty, including issues of gender equity, labor, fair pricing, and ecological concerns extending beyond permitted and prohibited inputs. At the time of writing, the degree to which these actors would be able to effectively do this while maintaining the official support of the Network remained unclear.

Building trust in a skeptical society

In its 2008 report on global experiences with PGS, the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation declared that “[t]he assumption that an organic certification system could be an expression of trust in the farmers/producers seems to have plucked at the heartstrings of many of the stakeholders in the organic sector worldwide” (Källander 2008, p. 19). Indeed, trust is widely considered to be the foundation upon which all other elements of a PGS initiative must be built. In addition, the issue of trust is implicit in the above discussion of how PGS may best achieve and maintain legitimacy in the eyes of a variety of stakeholders, from the producers being certified, to those consuming their products, to government agencies. As a result, considering the degree of trust various actors have in the system, as well as the factors that contribute to that trust (or the lack thereof), is essential for assessing the extent to which PGS can function as an effective alternative governance mechanism.

Levels of trust in PGS

As mentioned earlier, only 30 % of the Network consumers surveyed had a working understanding of PGS, with most relying instead on trust in individual producers and/or Network markets as a whole to serve as a guarantee of organic authenticity. The high levels of trust demonstrated by consumers in the honesty of Network producers might make the very notion of PGS seem almost redundant. Similarly, Zanasi et al. (2009, p. 54) suggest that, in the case of Brazil, levels of trust in small-scale organic producers tend to be so high that “it often happens that at the local market, consumers consider the Ecovida [PGS] Seal for organic products as being something superfluous”.

In spite of this, a regular consumer at the Chapingo market explained how PGS has the potential to act as a useful complement to such trust: “The trust I have in the products [sold at the market] is a result of the trust I have in the people. But I also know that there is a participatory certification system, and that helps me have an even higher level of trust”. Indeed, although only 27 % of the consumers surveyed reported relying on PGS to guarantee the organic quality of products sold at the Network markets, the vast majority (88 %) did feel it was important for the markets to have some form of certification system in place to ensure their continued integrity.Footnote 12 This is consistent with Ostrom and Ahn’s (2008, p. 22, italics added) assertion that, even within communities already characterized by high levels of social capital and trust, trust is “enhanced when individuals…are networked with one another, and are within institutions that reward honest behavior”. Consumers with awareness of PGS expressed high levels of trust in the process, giving it an average rating of 6 on a scale of 1–7. Notably, this was equal to the average trust rating given to third party certification.

In the case of producers, those surveyed actually reported higher levels of trust in PGS when compared to third-party organic certification. When asked for a rating on a scale of 1–7, the average producer score for PGS was 6, compared to an average of 4.8 for third-party certification. While a small number of producers did give third-party certification a slightly higher trust rating than PGS, 82.5 % reported having more trust in PGS. In addition, whereas only one respondent gave PGS a trust rating less than 3, 17 (or 21 %) gave ratings less than 3 to third party certification. A producer from Puebla helped to explain part of the reasons for this, noting that she had “more faith in participatory certification [when compared to third party certification] because we ourselves go and we see how people are producing”.

The relatively high levels of trust expressed with respect to the Network’s producers and PGS are important, as Ostrom and Ahn (2008, p. 22) note that “trust is the core link between social capital and collective action”. In other words, systems characterized by high levels of trust-based relationships amongst participants have greater potential to facilitate collective action. This suggests that PGS, and the Network within which that system is embedded, may indeed have significant capacity for collectively advancing a food sovereignty agenda in the country.

Preference for a non-profit certification process

Although the levels of trust reported in PGS and third party certification were not dramatically different, it is worth noting that those who favored PGS tended to express strong feelings regarding their distrust of the accredited organic certification agencies operating in Mexico. As a producer from the San Cristóbal local organic market put it: “I have absolutely no trust in [third party] certification. Those who have money just pay, and they get it”. Another producer at the same market echoed the sentiment, claiming that third party certification “is about paying, period. I don’t have any trust in it”. In organic markets across the country, similar concerns were raised.

Producers were not the only ones to demonstrate mistrust of the profit-oriented third party certifiers. One of the Network’s co-founders, also a regular consumer at the Chapingo market and a certified organic inspector, noted that considerable doubts exist regarding the validity of certifications carried out by one of the agencies operating in the country. She explained that “as a consumer [the concerns about that certifying agency] are a bit disappointing, especially because sometimes it’s the only label available and I have to say to myself, ‘I believe they’re cheating me’. And I’m lucky, because most consumers wouldn’t even know that, and that’s frustrating”. Another Network consumer without the same specialized knowledge shared essentially the same opinion, noting that “in any kind of company doing certification of anything there is a lot of corruption”.

These concerns about officially recognized and accredited forms of organic certification are perhaps not surprising considering that Mexico is characterized in general by extremely low levels of trust in institutions and authorities. Indeed, a study of global youth found that Mexicans exhibited “record distrust of all of their national institutions”, with only one-third trusting the media, 19 % the legal system, and 14 % the police (Reynié 2011, p. 73), and Camp (2007) suggests that, largely because of its history as well as more recent corruption problems, Mexico experiences lower than average levels of trust in authorities and institutions. Because this reality is the backdrop against which organic certification in Mexico takes place, the argument that, because of its presumed objectivity and professionalism, third party certification should be considered the only valid option loses some traction. Consequently, the not-for-profit, less institutional, less mainstream PGS alternative takes on added relevance.

Engendering trust through face-to-face relationships

While its not-for-profit nature may help give PGS an edge over third party certification in the eyes of many associated with the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets, perhaps the most important factor contributing to high levels of trust in PGS are the face-to-face relationships that form an integral part of the process. “I’ve never heard of participatory certification” explained a regular consumer who reported purchasing more than 90 % of her food at Chapingo’s local organic market, “but I do have trust in the products [at the market] because I trust the people here…On occasion I’ve spoken to producers about their production, but normally I don’t. I just trust them”. Indeed, having a direct relationship with a producer received the same high ratings of trust from consumers surveyed as both third party certification and PGS.

This finding is consistent with Zanasi et al.’s (2009) research on PGS in Brazil, and Moore’s (2006, p. 425) study of an Irish farmers’ market, which found that “the personal, facework connection was seen to be of paramount importance, operating as an alternative expert system” in which “personal reassurance was more important than technical organic certification”. The existence of such high levels of trust between producers and consumers suggests that, in spite of some of the doubts regarding legitimacy raised above, a solid basis exists within the Network upon which PGS may be strengthened over time.Footnote 13 The prevalence of strong, trust-based relationships further suggests that the Network’s markets—and the PGS structures that support their functioning—are making some progress with respect to challenging traditional market dynamics and enacting systems of trade more consistent with food sovereignty principles.

The threat of free-riding and non-compliance

It is important not to overlook the fact that, although respondents expressed generally high levels of trust in PGS, the process is not without its challenges and potential flaws. While face-to-face relationships and a not-for-profit orientation certainly help inspire faith, PGS initiatives do not exist in an ideal world where honesty can always be assumed. Rather, they are constructed within imperfect socio-economic systems in which a certain amount of doubt or mistrust may be necessary, and even beneficial. Conscious of this, even those research participants with the highest levels of trust in PGS often made comments to the effect that the potential for dishonesty should not be ignored.

One reason offered by respondents for maintaining a healthy skepticism about PGS was that, although the economic interests associated with it may be considerably less than in the case of third party certification, the ability to achieve certification via PGS and participate in the Network markets does offer the potential for some financial reward. According to one consumer in Puebla, “[t]he honesty of the producers is the key to participatory certification, and it is very good to show trust, but we also can’t be fools, because the reality is, if people see that they can sell a product for a slightly higher price, there are people who will try to exploit that”. Her suggestion was not that producers might engage in bribery within a PGS, but rather that they could take advantage of the trust-based nature of the system and lie about some aspects of their production.

This issue is consistent with Ostrom’s (1990) assertion that coping with possible ‘free-riders’ [i.e. individuals who seek the benefits of a collective resource—in this case, one afforded through access to a differentiated market—without complying with the rules that govern it] and ensuring broad-based commitment are some of the most common problems affecting efforts at collective action. Notably, fellow producers tended to express more concern than consumers about the potential for free-riding. This may be due to the fact that producers have a greater understanding of how PGS functions, and/or because they have a more vested interest in ensuring that the integrity of the local organic markets does not come into question. In some cases, internal market conflicts and competition contributed to a certain degree of suspicion. For example, one market coordinator noted that producers sometimes questioned their colleagues if the vegetables they were selling appeared to be too big, or too free of imperfections to be organic. A number of producers also noted that, in their opinion, cheating the system would be easy within the PGS framework. As one producer in San Cristóbal put it: “In the end, if I want to cheat you, I’ll cheat you, whether or not there is some kind of certification process”.

It should be noted that, in some cases, non-compliance with the PGS process was thought to occur somewhat unintentionally. For example, a former Network organizer active in the implementation of PGS cited the example of a family of corn producers who received fairly extensive extension assistance as part of their participation in a PGS, and made corresponding changes to their production, indicating a willingness to adopt organic techniques—particularly the composting of manure. Follow-up visits with this family demonstrated that some changes had been abandoned over time in favor of a return to traditional methods that did not comply with organic standards; however, the family made no attempts to hide this information, instead claiming that they were unaware their practices were unacceptable. While expressing some doubt regarding this apparent lack of awareness, the Network leader explained that “there are some people, especially the more elderly producers with very low levels of formal education, who, it’s not that they aren’t committed, but it seems to me that we need to have a more permanent extension presence with them”. A producer added that, “it’s often a question of culture. You can teach people how to do it [produce organically and comply with PGS procedures], and accompany them step by step, and they will do it, but once they’re on their own, not likely”.

Regardless of the reasons for cases of non-compliance, a Network leader explained that the participatory certification committees “have to have a response…They cannot say that they have done nothing in these cases, because they don’t have the capacity, or they haven’t had time to meet. They have to do something, because any consumer could ask at any time”. In accordance with the PGS ideal of encouraging producers to gradually move toward organic best practices with the assistance of the PGS committee, she explained that “[w]e can’t resolve it by saying ‘we’re kicking you out’, no. That option doesn’t even cross our minds. But the situation does make us think, and ask ourselves exactly what kind of a system do we have to implement, because we have to be making constant visits, because it seems that one visit is not enough”.Footnote 14

Notably, the issue of non-compliance has not been widely discussed in the published information regarding PGS, although Källander (2008) does make a general suggestion that it is important for PGS initiatives to have some kind of clearly defined mechanisms for dealing with non-complying producers. Explaining why non-compliance does not represent a significant challenge in the Brazilian context, Zanasi et al. (2009, p. 53) suggest that high levels of social cohesion within producer groups mitigate the potential for cheating, as “the fear of losing their reputation becomes an important factor preventing farmers from breaking the rules”. Further study would be required to examine the extent to which this is true in the Mexican context, and to establish whether cases of non-compliance are primarily related to a lack of education, lack of clear understanding of organic standards or PGS requirements, lack of motivation and commitment, or some combination of those and other factors. In the meantime, Ostrom’s (1990) conclusion that institutions for collective action function most effectively when a system of graduated punishments for non-compliance is in place could help inform work on PGS within and outside of Mexico.

Putting the ‘P’ in PGS

The above closely related discussions of legitimacy and trust highlight some of the challenges inherent in converting a conceptual framework, which consists of a number of ideals, into a system that can function in a practical way; however, perhaps the most basic demonstration of this tension relates to the participation required for PGS to function effectively. With the word included in the very title of the concept, the importance of participation cannot be overstated. One Network producer explained that, in her opinion, the best thing about PGS is that “it is a way of integrating all the different parts of the productive chain”. Another producer explained more specifically the benefits that this integration of different food chain actors offers: “…when you involve a diverse group like that, you make a movement stronger, because it isn’t depending on one person, or one agency, but instead on a whole community”.

The references to a systems approach that involves a diverse group of community-based actors in management of a regulatory structure certainly suggest that PGS has the potential to represent an innovative governance mechanism consistent with the principles of food sovereignty. Yet, while there was general consensus amongst research participants regarding how valuable broad-based, active and consistent participation is to PGS functioning, many noted that translating that ideal into practice is a significant challenge. This is consistent with findings from studies conducted on PGS around the world by IFOAM (2008) and Källander (2008).

Time constraints

One market coordinator explained how simply arranging meetings to deal with day-to-day market operations sometimes seemed impossible: “We don’t do meetings. It’s not like we don’t try, but you can’t just meet by yourself, and no one ever shows up”. She recognized, though, that in order for PGS to work things will have to change: “Now we have to start meeting, because we can’t do the participatory certification if we don’t, and that’s going to be the big challenge for us”. Many producers and consumers noted that time constraints made participation in PGS difficult. Although most did not criticize the volunteer nature of the PGS committees, instead making apologies for their lack of time and/or commitment, one producer did explicitly state that ensuring participation is difficult because “there’s the fact that no one wants to pay, so on top of being very complicated…you have people doing a lot of work and not getting paid for it….and no matter how committed you are, after 15 or 20 visits [on a volunteer basis], that’s it, no?” This is reflective of concerns raised by Nelson et al. (2010) that dependence on donated time and resources is a significant constraint to the development of PGS in Mexico. The particularly low levels of consumer participation in Mexico are also consistent with Källander’s (2008) finding that a lack of consumer presence in the system was one of the most important weaknesses facing PGS at the global level.

Lack of (real or perceived) expertise

In addition to time constraints, a lack of sufficient training (both real and perceived) presents another barrier to achieving necessary levels of PGS participation. IFOAM (2008) notes that “active participation on the part of the stakeholders results in greater empowerment, but also greater responsibility…”, and a number of Network members expressed concerns about their capacity to meet this responsibility. For example, even a producer well-known for his model agroecological practices did not feel comfortable participating on his market’s PGS committee because of a lack of formal training and technical expertise.

While this producer could arguably be considered a prime candidate for PGS work, in other cases feelings of insufficient training may have been more well-grounded. One market coordinator explained that, in her market, a group of producers and consumers was ready and willing to act as a PGS committee; however, they had been stalled by the fact that only one member possessed what the group perceived to be sufficient technical training in organic practices. Employed, and the parent of two small children, this person’s availability was limited, and the market coordinator noted that “even she doesn’t feel sufficiently trained…to provide technical training to the producers. And me even less so. I have a very ‘lite’ understanding of [organic production techniques], so how can I, in good conscience, go train others?”

Signs of progress

These barriers to realizing the participatory ideal of PGS are not uncommon in efforts at participatory styles of governance (see Gaventa 2006; Flora and Flora 2006) and, in spite of them, there were indications across the Network that suggest a shift toward greater participation may be gradually taking place. One of the most illustrative examples of this shift is a market where, for years, the PGS process was led by a trained agronomist and organic inspector. She explained how producer attitudes about PGS began to change as she gradually decreased her participation in the system:

I think that it used to be very easy for the producers to say ‘there is a certification system [in our market]. They come to review our production, and I comply with the changes they ask me to make.’ But then they had to start saying to themselves, ‘let’s see if this could work in a different way. Let’s meet as producers and review the questionnaires [for entry into the market] ourselves.’ And when I saw that starting to happen, I thought it was great. It’s great that the producers decided it wasn’t just about criticizing the system, but about saying ‘wow, there are a lot of producers on the waiting list to get into the market, and they’re not getting in because we’re not active enough’.

As they began to take more ownership of the PGS process, the former leader noted that producers often expressed insecurity about their abilities:

They started to say ‘we have a lot of doubts.’ Even [one of the most well-trained and formally-educated market leaders] told me that she wanted me to review the questionnaires and give my opinion. They began to see that things were not so easy. But I had supported them, in terms of explaining the standards, I had explained everything in our meetings, the questionnaires and everything, and we had gone through a process of improving them together, and we had made [certification] visits together, collectively, so they knew how to do it. They know how to do it. So let them do it. And, although they’re realizing that it is not easy, they are starting to do it, and that’s wonderful [because if] we are talking about participatory certification, the producers have to be the principal actors, the most interested in the process, because otherwise, they could just pay for a certification, but that would be far too expensive for them.

The changes happening in that one market are not an isolated experience. Rather, all of the markets participating in the study demonstrated some degree of progress toward solidifying PGS practice through increased participation and commitment to the idea, particularly on the part of producers and market coordinators. In Oaxaca, for example, a producer believed that PGS was gathering momentum in her market and she was able to articulate the practical benefits that her own participation had on her production: “Many of the production techniques we’re using right now are results of needing to comply with the notifications we received from the participatory certification committee. For example, we are now leaving more space between our production and our neighbors, and we’ve established permanent green fences to protect our production from contamination”.

Driven by a combination of ideological commitment to the concept, and the practical concerns of having to make the system functional to comply with Mexico’s organic legislation, the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets has played an important role in this transition to greater participation, for example by providing assistance for people to attend PGS training workshops. An agronomist working with one market’s participatory certification committee stressed the importance of that kind of training, explaining that “the producers’ dependence on [the two professional agronomists on the committee] was very strong. But now, since one of them attended a [PGS] training course, there has been a restructuring, and our role in things has decreased”. In 2010, the Ministry of Agriculture stepped in, offering the first significant sign of government support for PGS in the form of a joint project with the Network. Consisting of a series of workshops across the country, this project was meant to stimulate increased participation in, and adoption of, PGS; however, it remains too early to tell the degree to which such programs will be successful in the long run.

A final note regarding these signs of progress is that they are still rather fragile in nature. Specifically, the process of greater numbers of people taking responsibility for PGS is not linear, but rather appears to be a question of incremental advances, accompanied by periods of sliding backwards. The agronomist-inspector cited above, who also had considerable experience helping to organize PGS at the level of the Network as a whole, noted that, in the case of her home market, “sometimes I see that [the producers] are leaving [PGS] aside again, and so I get a feeling of ‘should I go back, or should I not go back?’ But if I go back, it seems likely that everyone will want to do things the way we did before, that they will want me to take care of everything again”. In order to avoid that, she made a conscious decision to put her concerns aside and let the committee find its feet without her, trusting that they will eventually manage to do so. The gradual nature of progress toward solidifying PGS should not be viewed as surprising, or even as negative; rather, it is reflective of Ostrom and Ahn’s (2008, p. 30, italics added) argument that “simply agreeing on an initial set of rules…is rarely enough. Working out exactly what these rules mean in practice takes time…The time it takes to develop a workable set of rules, known to all parties, is always substantial”.

Summary and conclusions

PGS as an innovative governance mechanism

The research presented in this paper leaves little question that PGS represents an innovative mechanism for food system governance. With its focus on devolving a significant degree of regulatory authority to the local level, empowering grassroots actors to make decisions, relying on—as well as engendering—relationships of trust, and fostering collective learning, it could certainly be considered an example of a locally-based institution for collective action. This represents a stark contrast to the dominant model of third party organic certification, with its centralized, vertically-structured governance mechanisms, assumption of distrust and disengagement between and amongst producers and consumers, and explicit separation of learning and capacity-building from certification. Thus, as a strategy for food system governance, PGS represents a far more significant challenge to the conventional food system paradigm than its third party alternative.

However, if PGS clearly represents an innovative governance model, a more challenging question to answer is the extent to which it is able to function effectively in practice. Our research demonstrates that PGS relies upon, and simultaneously helps to strengthen, relationships of trust within a food system. The relatively high levels of trust present within the markets employing PGS suggest that the system does indeed have significant capacity to serve as an effective regulatory institution. That effectiveness has been supported by the inclusion of PGS within Mexico’s national organic legislation, which grants official legal recognition to the process thereby enhancing its legitimacy, particularly in the eyes of potential critics.

While locally-grounded trust and recognition by authorities facilitate the ability of PGS to function as a viable alternative to third party organic certification, our research also highlighted a number of persistent challenges and concerns. Some of these relate to the fact that, as an institutional structure, PGS is still in its relative infancy and thus some of its operating procedures remain either too informal, too unclear, or too inconsistently applied to be perceived as reliable and/or legitimate by some actors. The Network is working hard to address these concerns and has made significant progress in recent years; however, the implementation of PGS remains, to some extent, a work in progress, and further development is needed to ensure effective monitoring procedures (including those governing non-compliance) are in place and are operationalized on a consistent basis. Gradual increases in the levels of participation in PGS are a sign that this development is moving forward, albeit not as quickly as some would like.

PGS as a tool to support food sovereignty

Beyond the question of its effectiveness as an innovative mechanism for food system governance, our research sought more specifically to explore the extent to which, as an alternative governance framework, PGS is able to support efforts to build food sovereignty. Here, again, the answer becomes more clear. Firstly, the Mexican case highlights the potential for PGS to support a transition of decision-making authority to the Global South as, unlike third party certification that is dominated by agencies with head offices in the Global North, the structure and functioning of PGS is determined by actors within the country where it is practiced. Secondly, our research demonstrates that PGS offers support, as well as opportunities for empowerment, to small-scale, resource-poor producers; specifically, by making the organic label—and associated price premiums—accessible to them, and by ensuring space for their active and meaningful participation in decision-making processes. Thirdly, unlike the export-oriented organic market that requires third party certification, PGS is explicitly dedicated to strengthening local and regional markets for organic products. Further, debates regarding what standards can or should be applied through PGS (beyond the national organic standard, which is used as a baseline) demonstrate the system’s capacity to extend beyond the input-substitution model of organics offered by most third party certifiers. Finally, by situating relationships of trust at the core of the framework, PGS represents a truly significant re-imagining of the trade dynamics that dominate both the conventional food system as well as the mainstream organic sector.

Final thoughts

Although PGS may still require a degree of further refinement and development to become a fully effective governance mechanism, there is no doubt that, even in its current state, it is creating opportunities “to transform dominant forces” (Wittman et al. 2010, p. 2), and is thus facilitating a transition toward greater food sovereignty. This has important implications for actors around the world engaging in alternative food initiatives with a food sovereignty orientation. It means that PGS can serve as a framework for the kind of “local control over politics and regulation” that Kloppenburg et al. (2000, p. 182) argue is essential for the success of alternative agri-food initiatives. Similarly, it presents a possible solution to the problem, identified by Seyfang (2007, p. 118), that actors participating in alternative food networks tend to “find little support within social institutions or social norms…”

In order for the potential of PGS to be fully realized, it is important that initiatives such as the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets continue their daily efforts to construct thriving models that demonstrate how conventional food system dynamics—including those that govern the mainstream organic sector—can be re-imagined. It is also important that researchers pay close attention to this emerging innovation in food system governance, as far more knowledge is needed with respect to the value that PGS can offer in a variety of contexts, and the most effective strategies for overcoming the barriers faced by those working on its development and implementation.

Notes

Although no definitive date marks the beginning of the organic movement, early pioneers included Sir Albert Howard, Lady Eve Balfour and Rudolf Steiner, who were active in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, and the popularity of the concept began to grow significantly in the 1960s and 70s as it was associated with the surge of a broader environmental movement.

Given the highly grassroots, and in many cases still experimental, nature of PGS initiatives, the numbers registered in the database are likely a significant underestimation of the actual numbers of producers and consumers engaged in some way in PGS around the world. This is borne out by stories presented in the PGS Task Force’s monthly newsletter, which recounts many experiences with participatory certification that are not registered in the database.

Although Ostrom’s “Common Pool Resource Institutions” typically refer to the governance of natural resources such as grazing lands, forests or fisheries, in the case of PGS the integrity of Mexico’s local organic markets can be considered a common pool resource, as it contributes significantly to the livelihood opportunities for the participating small- and medium-scale producers and is predicated on the ways in which productive lands and spaces are managed.

The remaining 40 % of producers differentiated their goods in some way from the certified organic products offered, for example through the use of signage or colour-coded table coverings.

Levels of concern regarding the validity of PGS were particularly high amongst members of one of Oaxaca City’s markets that, for a number of years, had been working collectively with the third party agency Certimex to achieve organic certification for its producers using an adapted version of the internal control system model.

There is currently no official seal used as an identifying label for products certified through PGS in Mexico; however the Mexican Network of Local Organic Markets’ logo is widely recognized and, although it is not affixed to products for sale, does go same way toward establishing the legitimacy of the PGS ‘brand’.

At the time of research, a 3 year project funded by the Canadian International Development Agency and administered by the Falls Brook Centre that had been central to the development of PGS capacity had come to an end, while a new short-term project with the Ministry of Agriculture was beginning. At the time of writing, cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture to facilitate the implementation of PGS in the country was ongoing.

The Network was granted permission to act as such a recognized organization, lending legitimacy to PGS as carried out by its member markets.

Notably, within the Network itself tensions exist between advocates of a more radically alternative food system vision and those with somewhat more conventional ideas regarding local organic markets.

The Brazilian legislation was eventually passed in 2003, and regulations that included recognition of three forms of organic certification (third party, PGS and social control) came into effect in 2007 (Meirelles 2010).

In addition to consumer preference for some kind of certification system to be in place it is worth remembering that, as mentioned earlier, the Mexican Organic Products Law makes such certification a legal requirement, and it is also beneficial for sales outside of Network markets where there may be no direct contact between producer and consumer, for example in the case of organic specialty stores.

As noted earlier, the high levels of trust reported by consumers in Network producers might suggest that constructing PGS is unnecessary. In Brazil, recognition of the unique circumstances created by face-to-face producer–consumer contact led the Brazilian government to officially recognize a third organic certification option. In cases of direct sale, producers can be granted certification based on their membership in a recognized producer or market association—a process referred to as certification by “social control” (MAPA 2008). This might be an avenue worth exploring in the Mexican context; however, the current structure of the country’s organic legislation might render it impossible, while interest on the part of Network producers to expand their marketing options through PGS might render it undesirable.

Since the research was conducted, the six markets that have fully developed PGS committees have made significant progress in establishing clear processes for addressing non-compliance.

Abbreviations

- IFOAM:

-

International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements

- PGS:

-

Participatory guarantee systems

References

Allen, P., and M. Kovach. 2000. The capitalist composition of organic: The potential of markets in fulfilling the promise of organic agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 17: 221–232.

Altieri, M.A., F.R. Funes-Monzote, and P. Petersen. 2012. Agroecologically efficient agricultural systems for smallholder farmers: Contributions to food sovereignty. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 32: 1–13.

Anderson, M.D., and A.C. Bellows. 2012. Introduction to symposium on food sovereignty: expanding the analysis and application. Introduction to guest-edited symposium of five papers. Agriculture and Human Values 29(2): 177–184.

Böstrom, M., and M. Klintman. 2006. State-centered versus nonstate-driven organic food standardization: A comparison of the US and Sweden. Agriculture and Human Values 23: 163–180.

Camp, R.A. 2007. Politics in Mexico: The democratic consolidation, 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Desmarais, A. 2007. La Via Campesina: Globalization and the power of peasants. Black Point: Fernwood Publishing.

Escalona, M.A. 2009. Los tianguis y mercados locales de alimentos ecológicos en México: su papel en el consumo, la producción y la conservación de la biodiversidad y cultura. Doctoral dissertation. Córdoba, Spain: University of Córdoba.

Flora, C.B., and J.L. Flora. 2006. Rural communities: Legacy and change, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Westview Press.

Gaventa, J. 2006. Triumph, deficit, or contestation? Deepening the ‘deepening democracy’ debate. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Gómez Tovar, L., M.Á. Gómez Cruz, and R. Schwentesius Rindermann. 1999. Desafíos de la agricultura orgánica. Mexico City: Editorial Mundi Prensa.

González, A.A., and R. Nigh. 2005. Smallholder participation and certification of organic farm products in Mexico. Journal of Rural Studies 21: 449–460.

Goodman, D. 2000. Organic and conventional agriculture: materializing discourse and agro-ecological managerialism. Agriculture and Human Values 17: 215–219.

IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements). 2008. Participatory guarantee systems: Case studies from Brazil, India, New Zealand, USA, France. Bonn: IFOAM.

IFOAM (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements). 2013. Sistemas Participativos de Garantía: estudios de caso en América Latina. Bonn: IFOAM.

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2011. http://www.inegi.org.mx. Accessed 25 Mar 2011.

Källander, I. 2008. Participatory guarantee systems—PGS. Stockholm: Swedish Society for Nature Conservation.

Kaltoft, P. 2001. Organic farming in late modernity: At the frontier of modernity or opposing modernity? Sociologia Ruralis 41(1): 146–158.

Kloppenburg Jr, J., S. Lezberg, D. De Master, G.W. Stevenson, and J. Hendrickson. 2000. Tasting food, tasting sustainability: Defining attributes of an alternative food system with competent, ordinary people. Human Organization 59(2): 177–186.

MAPA (Minstério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento). 2008. Controle social: na venda direta ao consumidor de productos orgânicos sem certificaçáo. Brasilia: MAPA.