Abstract

A number of developing countries have been experiencing high rates of ethnic fragmentation, corruption and political instability. The persistent poverty in many of these countries has led to an increased interest among both researchers and policy makers as to how these factors impact a country’s economic growth. Previous research has found mixed results as to whether ethnic fragmentation, corruption and political instability affect economic growth. However, this research has been focused on the direct impact of these variables on growth. This paper innovates by empirically modelling the impact of ethnic fractionalization and corruption on economic growth, both directly and indirectly through their role in affecting political stability. The analyses also add to the literature by testing a new data set with both fixed effects and GMM estimators. Results from a large panel data set of 157 countries from 1996–2014 finds that ethnic fractionalization and corruption negatively impact economic growth indirectly by increasing political instability, which has a negative direct effect on economic growth. Once the indirect effects are accounted for, ethnic fractionalization has no significant direct effect on growth. There is weak evidence to suggest that corruption may, in some countries, actually have a positive direct effect on growth by enabling firms to circumvent bureaucratic red tape, consistent with the “greasing the wheels” hypothesis. These results emphasize the importance of establishing strong institutions which are able to accommodate diverse groups and maintain political stability. Additional results find these implications to be particularly relevant for low-income and/or sub-Saharan African countries. The results also suggest that a country having a wide diversity of languages and religions need not be a hindrance to economic growth if a robust political system is in place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While the last two decades have seen a dramatic drop in poverty globally, the gains have been unequal. While rates of extreme poverty, as measured by living on $1.90 a day, have fallen below 20% across South and East Asia, they remain at 42% in sub-Sahara Africa (World Bank 2016b). In order to reduce these poverty rates, high rates of economic growth are necessary. This is especially true for countries with growing populations, such as many places in both sub-Saharan and Northern Africa. One of the challenges developing countries face in encouraging economic growth is corruption. The World Bank has found that $1 trillion is paid each year in bribes across the world, and that corruption’s negative impact on economic development is a multiple of that figure. According to Transparency International, 68% of countries worldwide have a serious corruption problem, and it has been shown that this disproportionately impacts lower income countries (Chew 2016). Both across and within countries, studies have shown that the poor end up paying the highest percentage of their income in bribes. For example, in Sierra Leone, high-income households pay 3.8% of their income in bribes, as compared to 13% for the poor (World Bank 2016a). Angola, one of the top five most corrupt countries, has 70% of its population living on $2 a day or less. Five of the top ten most corrupt countries are in sub-Saharan Africa, and 26 of the 31 countries classified as low-income countries by the World Bank are in sub-Saharan Africa (Transparency International 2015).

Given these facts, it is not surprising that there has been a growing emphasis on determining how factors such as corruption impact economic development. Research has been increasingly focused on how institutional, geographic, cultural, social and political factors affect growth. There has been concern regarding the possible negative impact of ethnic fractionalization on economic growth. Ethnic fractionalization refers to individuals within a country belonging to many different cultural, linguistic, and/or religious groups. Greater ethnic fractionalization may lead to higher rates of patronage and political instability. The literature has empirically tested the impact of many variables on growth, including corruption, ethnic fractionalization, income inequality, political instability, foreign direct investment, fertility, investment, education, and infrastructure. The literature has also shown that higher control of corruption leads to lower political instability (Mauro 1995). Income inequality increases instability up to a point, after which it reduces instability. Ethnic fragmentation reduces instability up to a point, after which it leads to higher instability (Blanco and Grier 2009). Despite the significant impact of these variables on political instability and the significant relationship between political instability and economic growth, the literature is still struggling to fully take account of these interrelationships.

This paper’s innovation comes through testing both the direct and indirect effects of corruption, inequality, and ethnic fractionalization on economic growth. This is accomplished by explicitly controlling for and modeling the indirect channel through which they impact economic growth by affecting political stability. The paper’s results find that the negative impact of ethnic fractionalization and corruption on economic growth are indirect. Both of these variables increase political instability, which then has a negative impact on growth. There is no direct impact of ethnic fractionalization or inequality on economic growth. And the direct impact of corruption on growth may, in some cases, be positive. These results appear to be driven by low income and/or sub-Saharan countries. The paper also adds to the literature via the usage of a larger and more recent data set than previous research. And the paper’s results are tested via both fixed effects and a generalized method of moments estimator.

The next section of the paper reviews some of the relevant literature and organizes the relationships that have been identified. The following sections discuss the sources of the data used, the methodology employed and empirical results. The paper concludes with a discussion of implications for the literature and policy makers.

2 Review of the literature

Several relationships have been established amongst corruption, income inequality, ethnic fragmentation, political instability, and economic growth. Research has found ethnic fractionalization, corruption, and income inequality to have significant effects on political instability. Ethnic fractionalization, corruption, and income inequality have also been shown to impact economic growth. Finally, studies have found a relationship between political instability and economic growth. The question that arises is whether the effects of political instability on economic growth are independent of the effects of ethnic fractionalization, corruption, and income inequality. To answer this, the following chain of effects is reviewed (Fig. 1):

2.1 Effects of corruption, income inequality, and ethnic fragmentation on political instability

Research has found corruption, income inequality, and ethnic fragmentation to have significant effects on political instability. Mauro (1995) observes a strong association between corruption, measured by bureaucratic efficiency, and political instability. Mauro finds that the correlation coefficient between corruption and instability is 0.67, and is 0.45 after controlling for per capita GDP. In a sample of 70 countries over the period 1960–1985, Alesina and Perotti (1993) find a positive relationship between income inequality and political instability. They measure income inequality as the share of the third and fourth quintiles of the population near 1960, noting its negative correlation with the richest quintile. The results suggest that political stability is enhanced by a wealthy middle class, implying less inequality, and that income distribution does not affect investment after controlling for political stability. This relationship is important because it implies that although increasing the tax burden on capitalists and investors through fiscal redistribution could hinder investment, the reduction in inequality may reduce political tensions and instability. Further supporting the association between income inequality and political instability is Blanco and Grier’s (2009) identification of a nonlinear relationship between income inequality and political instability in a panel of 18 Latin American countries from 1971 to 2000. Increases in income inequality are associated with increases in political instability until the Gini coefficient reaches 0.45, after which further increases in income inequality are associated with decreases in political instability. The Gini index is the most prevalent measure of income inequality in the literature. Blanco and Grier’s findings support the claim that the effect of inequality on instability is a nonlinear function of the Gini coefficient (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006a). Acknowledging the political complications that would arise if policymakers tried to reduce inequality through changes in tax structures, Blanco and Grier propose reducing inequality through educational reforms.

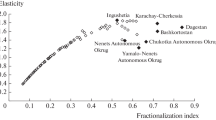

Blanco and Grier also find a nonlinear relationship between ethnic fractionalization and political instability; increases in ethnic fractionalization are associated with decreasing political instability until fractionalization reaches a level of 0.33, after which further increases in ethnic fractionalization are associated with greater political instability. The ethnic fractionalization index used is from Alesina et al. (2003). Blanco and Grier’s study is particularly relevant because Latin America is one of the most unequal and ethnically diverse regions. However, the effect of ethnic fractionalization on political instability is ambiguous. Several empirical studies have found intermediate levels of fractionalization, measured by an ethnolinguistic fractionalization index, lead to the worst case of political instability (Ranis 2009). This is attributed to ethnic fractionalization leading to the under-provision of non-excludable public goods and favoring excludable patronage goods (Alesina and La Ferrara 2005; Easterly 2001; Easterly and Levine 1997; Kimenyi 2006). Ethnic fractionalization can also lead to entrenched elites blocking necessary innovations and change in an economy (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006b). There is a lack of consensus on the effect of ethnic fractionalization on political instability. Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2005) propose that ethnic and religious fractionalization increase the probability of civil wars. Rather than using indices of fractionalization, Montalvo and Reynal-Querol use indices of polarization, which captures the presence of a large, undivided ethnic minority facing an ethnic majority. Annett (2001) observes higher levels of ethnic fractionalization, as measured through indices of ethnolinguistic and religious fractionalization, are associated with greater political instability.

Political instability is often synonymous with a lack of strong, democratic institutions. Researchers such as La Porta et al. (1999) have found that increased ethnic fractionalization can reduce the quality of institutions. And whether ethnic fractionalization leads to conflict or not can be a function of the quality of the country’s institutions (Reynal-Querol 2002). Bad institutions can be self-reinforcing, becoming a long-run hindrance to a country’s political stability and development (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). Through the usage of interaction terms and stratified samples, researchers have found that the negative impact of ethnic fractionalization on economic growth is increased by having less democratic institutions (Collier 2000, 2001; Easterly 2001).

2.2 Effect of corruption, income inequality, and ethnic fractionalization on growth

It has also been found that corruption, income inequality, and ethnic fractionalization have direct effects on growth. Mauro (1995) finds a significant negative association between corruption and investment. The results indicate that an improvement of one standard deviation in the corruption index, meaning less corruption, is associated with the investment rate increasing by 2.9% of GDP. Mauro also tests corruption’s association with economic growth rates, and finds a significant negative correlation between corruption and average GDP growth rates. Using the bureaucratic efficiency index as a measure of corruption, a one-standard-deviation improvement in the index is associated with a 1.3% increase in the annual GDP per capita growth rate. Davoodi and Tanzi (1997) find that bureaucratic malpractice results in public funds being allocated to where bribes can be more easily collected, indicating that corruption results in public spending being directed towards low-productivity projects rather than value-enhancing investments. Blackburn et al. (2010) construct a simple neo-classical growth model which allows for the two-way causal relationship between corruption and economic development. They propose that corruption hinders economic growth, and is then affected by the subsequent lack of development.

Alesina and Rodrik (1994) find that after controlling for initial levels of income, inequality in income and land distribution is negatively correlated with subsequent economic growth rates due to higher taxation rates. The results suggest that an increase in the land Gini coefficient of one standard deviation would lead to growth rates falling by 0.8 percentage points per year.

There have been many studies linking ethnic fractionalization to lower economic growth. Mo and Papyrakis (2014) establish a negative association between ethnic fractionalization and economic growth, mainly attributable to the transmission channels of corruption, investment, fertility, and conflict. The results indicate that there is a 2.04% difference in growth rates between ethnically homogeneous and fully fractionalized societies. Ethnic fractionalization is associated with reduced infrastructure investment, due to the various ethnic groups preferring different capital goods. Mo and Papyrakis find investment accounts for 25% of the overall negative association between fractionalization and economic growth. Corruption is more prevalent in ethnically diverse societies due to ethnic favoritism, and they find that corruption accounts for 30% of the negative association between fractionalization and growth. Ethnically diverse societies often exhibit higher fertility rates. Ethnic groups encourage pronatalism to increase the relative group size, thus increasing political leverage and benefits. Mo and Papyrakis find that fertility accounts for 17% of the negative association between ethnic fractionalization and growth. Ethnic fractionalization is also correlated with conflict and thus more loss of life, but the results indicate conflict only accounts for 1% of the negative association between fractionalization and growth. The negative correlation between ethnic fractionalization and investment and corruption accounts for more than half of the negative correlation between ethnic fractionalization and growth, and corruption is the most significant indirect transmission channel, evidence that corruption is a key determinant of growth. Collier and Hoeffler (1998) propose that ethnolinguistic fractionalization reduces trust, increases transaction costs, and negatively impacts economic development overall. Easterly and Levine (1997) argue that ethnically polarized societies cannot agree on the provision of public goods and are inclined to participate in rent-seeking activities. This is consistent with the evidence that ethnic diversity can reduce growth in the presence of weak institutions or political instability (Collier 2000, 2001; Easterly 2001).

The literature indicates low levels and very high levels of ethnolinguistic fractionalization are less threatening to economic development than intermediate levels (Ranis 2009). This is consistent with the finding that intermediate levels of ethnic fractionalization are associated with high levels of political instability; since political instability is negatively correlated with growth, it logically follows that intermediate levels of ethnic fractionalization are associated with higher instability and lower growth. Intermediate levels of ethnic fractionalization are associated with high levels of ethnic polarization; this implies that high polarization is associated with higher political instability and lower growth (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol 2005). The best measure of fractionalization is not established; some economists find that polarization is more relevant when two opposing groups are close in terms of their power, since this may result in poor policy, more instability, and lower economic development (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol 2005; Easterly and Levine 1997; Esteban and Ray 1994). Research suggests that although decentralization may reduce fractionalization because local communities are likely to exhibit less fractionalization, the abundance of groups at the local level may result in no group being strong enough to “mobilize an ‘encompassing interest’”. The lower fractionalization resulting from vertical decentralization may imply higher levels of polarization (Sasaoka 2007).

Alesina et al. (2003) construct a measure of ethnic fractionalization using a combination of racial and linguistic characteristics to account for heterogeneity of both race and language. This is important because in areas such as Latin America, data on racial distinctions differ greatly from linguistic distinctions. Their ethnic fractionalization index shows more fractionalization than the primarily used Soviet index, since the Soviet index does not account for the fact that many groups which speak the same language may be racially diverse. They conclude that both their ethnic fractionalization index and an index of linguistic fractionalization have greater impacts on economic growth than religious fractionalization. Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2005) find that religious polarization and fractionalization do not directly affect growth. The analysis of Reynal-Querol (2002) finds religious differences within a country having a significant impact on growth but not linguistic differences.

2.3 Effect of political instability on growth

Research has established a connection between political instability and growth. Alesina and Perotti (1993) find that political instability leads to lower investment, and therefore lower economic growth. An increase of one standard deviation in the measure of political instability results in the share of investment in GDP falling by 4 percentage points. The theory is that greater political instability deters investors because of increased uncertainty regarding future economic policy and threats to property rights, as well as disruption of productive activity. Roe and Roe and Siegel (2011) find that political instability impedes financial development, and the literature indicates that financial development promotes economic growth. They propose that lower growth results from instability diverting the attention of public officials, capital leaving the country, and the emigration of skilled workers. Research has found that instability, measured by the number of revolutions and coups per year and the number of political assassinations per year relative to the population size, negatively influences economic growth (Barro 1991). Greater political instability, measured as the propensity of a government collapse, is also associated with lower economic growth (Alesina et al. 1996).

Goren (2014) tests a model of direct and indirect effects of ethnic fractionalization on economic growth. Using the Barro-Lee 1960–1999 data set, Goren employs a SUR approach to test the effects of ethnic fractionalization on five year average growth rates. Goren (2014) finds that political instability reduces growth and that ethnic fractionalization’s impact on growth is direct, not indirect. Our paper is building on the work of Goren (2014) but is distinguished from it in significant ways. First, our paper puts together a more recent (1996–2014) and larger data set (1791 vs. 691 observations). Second, Goren does not distinguish between linguistic and religious fractionalization. There is evidence in the literature to suggest that religious and linguistic fractionalization have different effects (Reynal-Querol 2002). Goren’s focus is on testing fractionalization versus polarization, rather than the different aspects of fractionalization. Econometrically, there are differences as well, especially with the additional robustness checks using GMM.

2.4 Other factors in economic growth

There are several other factors which the literature has found to impact economic growth. Some of the literature regarding these variables will be discussed briefly, as these will be included as control variables in the analyses. Research has shown fertility, investment, education, infrastructure, and initial income to be significantly related to GDP growth rates. Levine and Renelt (1992) find investment to be a robust determinant of economic growth, and the relationship between investment and growth is supported throughout the literature (Mauro 1995; Mo and Papyrakis 2014). Research has identified a relationship between fertility and economic development, with higher birth rates reducing economic growth through reduced investment, and declining fertility rates having positive effects on per-capita income growth (Brander and Dowrick 1994). The negative association between fertility and economic growth is further supported by the work of Mo and Papyrakis (2014). The literature has established a connection between education and economic growth, with evidence that increases in education are associated with increased technological innovation (Nelson and Phelps 1966; Benhabib and Spiegel 1994). There has also been significant research on the positive effect of infrastructure on economic development, supported by the finding that economic output varies with investment in core infrastructure (Aschauer 1990). There has also been a debate in the literature regarding the impact of initial GDP per capita on economic growth. This has focused on whether countries are experiencing increasing or decreasing returns to scale in their economic growth (Ades and Glaeser 1999). A county’s openness to trade can also impact growth, either on its own or in an interaction with its initial income level (Ades and Glaeser 1999; Alesina et al. 2000).

3 Data and variables

The dataset used for the empirical analysis consists of 157 countries for the period 1996 to 2014. The dataset is an unbalanced panel dataset, as there is not data on all the countries for each year. There are a total of 1791 observations in the sample. Table 1 lists the variables included in the regressions and provides explanations and summary statistics.

3.1 Dependent variables

The variable used for political instability is the measure of political stability and absence of violence/terrorism from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). The WGI compiles information from existing data sources reporting the views on the quality of governance. The types of sources include surveys of households and firms, commercial business information providers, non-governmental organizations, and public sector organizations. The sources for the measure of political stability are as follows: 1) Economist Intelligence Unit Riskwire & Democracy Index; 2) World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report; 3) Cingranelli Richards Human Rights Database and Political Terror Scale; 4) iJET Country Security Risk Ratings; 5) Institutional Profiles Database; 6) Political Risk Services International Country Risk Guide; 7) Global Insight Business Conditions and Risk Indicators; 8) Institute for Management and Development World Competitiveness Yearbook; 9) World Justice Project Rule of Law Index. The aggregate WGI measure of political stability and absence of violence ranges from approximately −2.5, indicating very low stability, to 2.5, indicating very high stability. To create a measure of political instability, the WGI political stability measure was multiplied by −1; thus, the political instability measure ranges from −2.5, indicating very low instability, to 2.5, indicating very high instability. The second dependent variable is economic growth. Growth is measured as the annual change in real Gross Domestic Product per capita. This is taken from World Development Indicators and is measured in constant US dollars.

3.2 Independent variables of interest

The measure for corruption was also retrieved from Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). The aggregate WGI measure of control of corruption ranges from approximately −2.5 to 2.5, with higher values indicating better governance. To create a measure of corruption, the WGI control of corruption measure was multiplied by −1; thus, the corruption measure ranges from −2.5, indicating very low corruption, to 2.5, indicating very high corruption. The WGI corruption measure was preferred to that available from Transparency International as WGI offers a much larger panel data set.

Income inequality is measured through the World Bank estimate of the Gini Index. The Gini measures the extent to which the distribution of income among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. The Gini index ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating perfect equality and 100 indicating perfect inequality. The Gini index is the most commonly used measure of income inequality in studies of economic growth. There were many missing values for the Gini index over the period studied. The number of observations fell from 1791 to 754 with the inclusion of the Gini; therefore, regressions were run both with and without the Gini index. Results including the Gini Index variable are in Appendix 1.

The measure of linguistic fractionalization was obtained from Ethnologue: Languages of the World, a comprehensive catalogue of the world’s known living languages. Ethnologue reports linguistic diversity based on Greenberg’s diversity index, which represents the probability that any two people of the same country selected at random would have different mother tongues. The measure ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no diversity and 1 indicating total diversity. The computation is based on the following formula:

where sij is the share of language i (i = 1...N) in country j.

There were some missing values for the linguistic fractionalization variable. In order to make a more complete data set, it was necessary to impute some values for this variable. This was performed using the interpolation and extrapolation features of Stata’s mipolate command. While linguistic fractionalization has a high level of variance across countries, it does not exhibit much short-run variance within a country. This makes linguistic fractionalization an ideal candidate for missing value estimation. The characteristics of the original series which contained missing values and the data series which included the imputed missing values were compared and they were not significantly different. The data characteristics compared were the mean, minimum, maximum, variance, skewness, and kurtosis.

The measure of religious fractionalization was constructed using the World Religion Dataset: National Religion Dataset from the Association of Religion Data Archives. The dataset contains information on the number of adherents by religion in each of the states in the international system; some of the religions are further divided into religious families. The same formula used for linguistic fractionalization was used for the construction of a religious fractionalization measure, where sij is the share of religion i (i = 1...N) in country j. The calculated measure indicates the probability that any two people of the same country selected at random would practice different religions. The religious fractionalization measure ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating no religious diversity and 1 indicating total religious diversity. Missing values were addressed using the same methodology and checks as with the linguistic fractionalization variable. It should be noted that the fractionalization measures used in this paper are measured only on religion and linguistics. These do not measure genetic diversity of the population. Therefore, this paper’s results do not address the validity of the “out of Africa” hypothesis of Ashraf and Galor (2013).

3.3 Control variables

The measure of FDI consists of equity capital, reinvestment of earnings, other long-term capital, and short-term capital as shown in the balance of payments. They are the net inflows in the reporting economy from foreign investors seeking a management interest in an enterprise in the reporting economy. The FDI data is obtained from the World Development Indicators, and is measured as net inflows in current US dollars. The distribution for FDI is skewed, so for regression purposes, the log was taken to normalize the data. The measure of investment is Gross Capital Formation, as a percentage of GDP, reported by the World Development Indicators. It represents the spending on additions to the fixed assets of the economy plus net changes in inventory levels. WDI defines fixed assets as land improvements; plant, machinery, and equipment purchases; and construction. Inventory is defined as stocks of goods held by companies to meet fluctuations in production, sales, and “work in progress”. Initial real GDP per capita is included as a control variable and is also from WDI.

The total fertility rate indicates the number of children that a woman would give birth to if she lived through her childbearing years. The data is obtained from World Development Indicators. The measure of education used in this paper is the primary school completion rate for both sexes, calculated as the total number of new entrants in the last grade of primary education as a percentage of the total number of students who are of the theoretical entrance age to the last grade of primary. It can be greater than 100% because of over-aged or under-aged children who enter primary school late or early, and due to repetition of grades. This measure was chosen because it captures how many students actually reach their last year of primary education, by which point it is more likely that they will finish the final year. Choosing a different measure such as the gross enrollment ratio is not as indicative of how many people obtain a certain level of education, since they may not reach the final year. Also, government expenditure on education may not reflect how much of the population is educated, since the government may not spend efficiently or equally across the population. The data is obtained from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Access to improved water sources and mobile subscriptions are used as measures of investment in infrastructure. These are used commonly in the literature as measures of infrastructure, and thus quality of life, since access to improved water would imply health benefits, and mobile subscriptions mean the population is more connected and has access to technology. The percentage of the population with access to improved water sources is considered for both the urban population and rural population. It is important to consider the rural population separately, since infrastructure in rural areas is less common than urban areas in less developed countries. Improved water sources include piped water on premises and other sources such as public taps or standpipes, protected dug wells, and rainwater collection. The data on mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people covers subscriptions to a public mobile telephone service that provide access to the public switched telephone network. These variables are taken from WDI. To ensure that some missing values did not significantly reduce the number of observations in the sample, values measuring access to improved water sources, both rural and urban, were interpolated and extrapolated to cover the dataset period. Infrastructure variables tend to not vary significantly on an annual basis within countries. The original and full data series were compared and were not significantly different.

Additionally, a time trend variable is included in the regressions to account for general trends in the data over time. The time trend variable was found to be more significant than using year dummy variables. In order to test the impact of openness, the ratio of (exports + imports) to GDP was taken from WDI. Due to the significant loss of observations from the inclusion of the openness variables, these results are included in Appendix 2 rather than in the body of the paper. For similar reasons, results including a variable for economic freedom (taken from the Heritage Foundation) are also included in Appendix 2.

3.4 Instruments: Political rights and civil liberties

There are two variables which will be used as instruments in the analyses. These two variables, political rights and civil liberties, are both taken from Freedom House. Freedom House issues global reports on political rights and civil liberties for 195 countries, evaluating the real-world rights and freedoms of individuals and acknowledging that political rights and civil liberties can be affected by both state and non-state actors such as insurgents. The ratings are based on a compilation of news articles, academic analyses, reports from NGOs, and individual professional contracts. The ratings range from 1 to 7, with 1 representing the least political rights and civil liberties (least free), and 7 representing the most political rights and civil liberties (most free). An additional discussion of these instruments, including their testing, will be done in the methodology section.

4 Methodology

The focus of the analysis is on determining the direct and indirect effects of corruption and fractionalization on economic growth. These factors impact growth directly but also indirectly through political instability. An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) approach with two separate equations for economic growth and political instability, respectively, was investigated. However, there was a significant correlation between the two equation’s error terms, which means that estimating these equations separately could be problematic. Also, there may be an endogenous relationship between economic growth and political instability; in the OLS model, the effects of political instability on growth could be biased by the feedback effects from growth on instability. A Hausman test rejected the null hypothesis that political instability was exogenous. Thus, it was concluded that a Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) approach was necessary.

To account for time invariant factors that are specific to each country and may not be observed, fixed effects are utilized. A Hausman test was run to check the validity between fixed and random effects (which would be another option with panel data). However, the Hausman test rejected the null hypothesis that random effects would be a consistent estimator at the 1% level, with a p-value of 0.000. Therefore, it is preferable to run the regressions using country-level fixed effects rather than potentially biased random effects.

There is the possibility that economic growth may exhibit non-stationarity which would make a 2SLS produce potentially biased results. An augmented Dickey-Fuller test rejected the null hypothesis of non-stationarity with a p-value of 0.00. As an additional test of robustness, Appendix 2 contains the results from a Generalized Method of Moments estimator. These results are generally consistent with the 2SLS analysis and support the notion that the paper’s results are not reliant on particular assumptions being made regarding distributions of the error terms.

In the first stage, the 2SLS approach creates an estimate of political instability. In the second stage, the 2SLS approach uses the model-estimated values of instability from the first stage in place of the actual political instability values to estimate growth. The equations from the two stages are shown below.

-

Stage 1:

-

Stage 2:

The subscripts i and t refer to country i at time t. Following the independent variables are time invariant country fixed effects (vt) and the regression error term (εi , t, ϵi , t).

To use the 2SLS approach, instrumental variables must be included in the equation estimating political instability, and these should have a significant impact on instability but should not have a direct impact on GDP growth. The two variables identified are political rights and civil liberties. A lack of political rights and civil liberties can create unrest in the country’s population and thus directly contribute to political instability. The two instrumental variables are found to have significant negative effects on political instability at the 1% level, meaning that increases in political rights and civil liberties are associated with lower levels of political instability. These results confirm the importance of political rights and civil liberties with regards to political instability. For instruments, it is important that they not have a direct impact on economic growth. There is a sizable literature which does not find a significant effect of political rights or civil liberties on economic growth (Piatek et al. 2013; Mulligan et al. 2004; Dawson 2003; Ali and Crain 2002; Alesina et al. 1996; Barro and Sala-i-Martin 1995; De Haan and Siermann 1995, 1996). As another test of the appropriateness of the instruments, the Sargan overidentification test was used. The test failed to reject the null hypothesis of instrument validity. There is a concern that there could be reverse causality (i.e. that growth may impact political rights and/or civil liberties). A Davidson-McKinnon test was run and the null hypothesis for exogeneity of economic growth with respect to the instruments failed to be rejected.

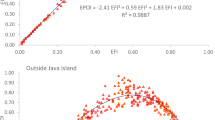

5 Results

The results in Tables 2 and 3 show both direct and indirect effects, emphasizing the importance of the two-stage approach. Corruption and linguistic fractionalization have positive and significant effects on instability at the 1% level, implying that greater levels of corruption and ethnic fractionalization result in higher levels of political instability. Instability has a negative effect on growth, and is significant at the 1% level, implying that higher levels of political instability hinder economic growth. Linguistic fractionalization and corruption do not have significant direct effects on economic growth, suggesting that the effects of ethnic fragmentation and corruption on growth is primarily due to their impact on political instability (Fig. 2).

5.1 By income levels

Neoclassical growth models have found initial income levels to be inversely related to subsequent economic growth rates; Barro (1991) finds that increases in initial income levels are associated with lower economic growth when human capital is held fixed. The sample is divided into quartiles, based on GDP per capita levels in US dollars in 1996 (the beginning of the sample time period). The lowest income level consists of countries whose initial GDP per capita was below $467.56. The second level includes countries whose GDP per capita in 1996 was between $467.56 and $1455.77, the third level is between $1455.78 and $4066.84, and the highest level is countries whose GDP per capita was above $4066.84. The 2SLS system is then run by income level.

For the low-income countries, corruption and linguistic fractionalization have positive and significant impacts on political instability, and instability has a significant negative effect on GDP growth at the 1% level. Corruption and linguistic fractionalization both have positive and significant effects on GDP growth, suggesting that for low-income countries, greater levels of corruption and fractionalization negatively impact growth through political instability, and once those effects are accounted for, they are positively correlated with growth. However, the results are very different for the three other income levels. Corruption and linguistic fractionalization are significant determinants of political instability for the second and third income levels, but for the highest-income countries, linguistic fractionalization is no longer significant. Political instability, corruption, and fractionalization are not significant determinants of GDP growth for the second, third, or fourth income levels. The implications of these results is that political instability, corruption, and ethnic fragmentation primarily impact development in low-income countries, and do not have significant effects on growth once a country has reached a certain level of income. This conclusion is supported by excluding low-income countries from the 2SLS regression; political instability, corruption, and both measures of fractionalization are insignificant on growth. These results can be seen in Tables 2 and 3. If only high-income countries are excluded, corruption and linguistic fractionalization are both positively significant determinants of political instability, as they were in the full-sample regressions, and political instability has significant negative impacts on GDP growth. This implies that the low-income countries may be primarily driving the significant negative effect of instability on growth.

5.2 Regional effects

The literature has shown regional effects to have significant impacts on variables such as GDP growth, political instability, corruption, and fractionalization. Therefore, this paper excludes certain regional groups to ascertain whether the effects are significant across all regions. Political instability still has a significant negative effect on GDP growth when excluding Latin American and Caribbean countries, and also when excluding Middle East and North African countries.Footnote 1 However, when excluding sub-Saharan African countries from the sample, political instability no longer has a significant impact economic growth, and neither do corruption, linguistic fractionalization, or religious fractionalization. The results excluding sub-Saharan African countries can be seen in Tables 2 and 3.

Corruption still positively impacts instability, but linguistic fractionalization is no longer significant. For the sub-Saharan African countries, corruption and linguistic fractionalization are both significant determinants of political instability at the 1% level, and political instability negative impacts GDP growth at the 1% level. Corruption positively impacts growth for sub-Saharan countries at the 5% level, and linguistic fractionalization positively impacts growth at the 10% level. This suggests that linguistic fractionalization negatively impacts growth in sub-Saharan African countries indirectly through political instability, but on its own, has a small positive impact on growth. Overall, the fact that political instability, corruption, and linguistic fractionalization do not significantly affect economic growth when excluding sub-Saharan African countries implies that this regional group is largely driving the results in the full-sample regressions. This result can be considered consistent with the hypothesis of Desmet et al. (2015) that ethnolinguistic fractionalization is most damaging when it overlaps with culture as it does in sub-Saharan Africa.

5.3 Other variables

This paper primarily focuses on the effects of political instability, corruption, and ethnic fractionalization on GDP growth; however, there are some control variables which yielded significant results. Rural access to improved water sources positively impacts political instability at the 1% level. This may be because access to water implies better living conditions, and as living conditions improve in rural populations, individuals are more likely to rise into the middle class and demand more from the government. Investment has a negative effect on instability at the 10% significance level, supporting the theory that increases in investment are beneficial and reduce instability. The correlation may also work in the other direction, as investment is more prominent in countries with politically stable regimes. Fertility has a positive effect on political instability at the 5% level. Political rights and civil liberties are both significant and negative at the 1% level, supporting their use as instrumental variables which directly impact political instability. Mobile subscriptions and FDI do not have significant effects on political instability. To account for the possibility of investment or FDI affecting instability in the following period, lagged values for investment and FDI are tested. Lagged investment and FDI do not significantly impact instability, suggesting that in the sample, investment primarily affects instability in the current period and FDI does not significantly affect instability.

Urban access to improved water sources has a significant negative impact on economic growth at the 10% level. There is no a priori explanation for this result. It could be that this is the result of urban bias in terms of government spending which results in slower growth coming from rural areas. However, that is conjecture and beyond the scope of this study. Rural access to improved water sources positively impacts GDP growth at the 1% significance level, suggesting that as the rural population’s living standards improve, growth also increases. Investment and FDI both have positive effects on GDP growth at the 1% significance level. Linguistic and religious fractionalization, fertility, and education do not have significant impacts on economic growth. Lagged FDI does not significantly impact GDP growth, suggesting that in this sample, FDI is primarily related to growth in the current period through a contemporaneous correlation. However, lagged investment has positive and significant impacts on GDP growth, which indicates that there is not a contemporaneous correlation.

For low-income countries, the infrastructure measures are no longer significant on political instability, nor are the investment or education variables. FDI is still not significant on political instability. Fertility is still significant and positive. Low-income countries do not receive as much investment as higher-income countries, so there may not be enough evidence for a significant relationship between investment and instability to be established. Interestingly, in low-income countries, mobile subscriptions has a significant negative impact on growth, but access to improved water sources is no longer significant, nor are investment or FDI. Education is positively correlated to growth, and the coefficient on fertility is actually positive and significant. With more people completing primary school in low-income countries, and thus greater educational attainment, people may be more likely to rise into the middle class and increase their wealth.

6 Conclusions

This paper provides a new way of viewing the relationships between ethnic fractionalization, corruption, political instability, and economic growth. The innovation comes by modelling both the direct effects of corruption and ethnic fractionalization on economic growth as well as their indirect effects via political instability. Empirical testing supports the importance of accounting for these complex relationships as both corruption and ethnic fractionalization increase political instability which consequently lowers economic growth. This approach also yields the interesting result that ethnic fractionalization and corruption do not have significant direct impacts on economic growth; they are affecting growth primarily indirectly through political instability. And corruption’s direct impact on growth may actually be positive in some cases once the negative effect on political instability has been parsed out. The incorporation of direct and indirect effects contributes to the literature by providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms at work which is crucial for the creation of sound policy. Importantly, these results are robust to the estimation method chosen.

The results from this paper are driven by low-income and/or sub-Saharan African countries. This makes the implications especially important for policy makers as these are precisely the countries which are in dire need of sustained economic growth. The foremost implication for policy makers is an emphasis on political institutions. Having a high rate of ethnic fractionalization does not necessarily hinder a country’s economic growth if they have stable, inclusive political institutions in place. Countries must be concerned not only with corruption’s effects on business but also with how it may weaken their political institutions.

This paper also provides some avenues for future research. This paper represents an attempt to model the complex nature of interrelationships among these variables and economic growth. Additional interrelationships and layers of complexity can be modeled and tested. Also, the differential results by region and income classification may yield some interesting additional investigations. There are potential questions of causality between ethnic fractionalization and institutional quality that could merit further research. In particular, it is possible that the relationship between ethnic fractionalization and institutions/instability could be bi-directional in nature. Another interesting extension of this research would be to incorporate the impact of immigration on ethnic fractionalization, political instability and economic growth. In particular, the impact of ethnic fractionalization on political stability and growth could vary based on whether it comes from the native-born versus immigrant populations.

Notes

For the sake of brevity, these results are available on request.

For the sake of brevity, the GMM results with 1791 observations are available on request.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2006a) Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press, Boston

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2006b) Economic backwardness in political perspective. Am Polit Sci Rev 100(1):115–131

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2012) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business, New York

Ades AF, Glaeser EL (1999) Evidence on growth, increasing returns, and the extent of the market. Q J Econ 114(3):1025–1045

Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R (2003) Fractionalization. J Econ Growth 8:155–194

Alesina A, La Ferrara E (2005) Ethnic diversity and economic performance. J Econ Lit 43:762–800

Alesina A, Ozler S, Roubini N, Swagel P (1996) Political instability and economic growth. J Econ Growth 1(2):189–211

Alesina A, Perotti R (1993) Income distribution, political instability, and investment. NBER Work Pap Ser 4486:1–33

Alesina A, Rodrik D (1994) Distributive politics and economic growth. Q J Econ 109(2):465–490

Alesina A, Spolaore E, Wacziarg R (2000) Economic integration and political disintegration. Am Econ Rev 90(5):1276–1296

Ali AB, Crain WM (2002) Institutional distortions, economic freedom, and growth. Cato J 21(3):415–426

Annett A (2001) Social fractionalization, political instability, and the size of government. IMF Staff Pap 48(3):561–592

Aschauer DA (1990) Why is infrastructure important? Fed Reserve Bank Boston Conf Ser 34:21–68

Ashraf Q, Galor O (2013) The ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative economic development. Am Econ Rev 103(1):1–46

Barro RJ (1991) Economic growth in a cross-section of countries. Q J Econ 106(2):407–443

Barro RJ, Sala-i-Martin X (1995) Economic growth. McGraw-Hill, New York

Benhabib J, Spiegel MM (1994) The role of human Capital in Economic Development: evidence from aggregate cross-country and regional U.S. data. J Monet Econ 34(2):143–173

Blackburn K, Bose N, Haque ME (2010) Endogenous corruption in economic development. J Econ Stud 37:4–25

Blanco L, Grier R (2009) Long live democracy: the determinants of political instability in Latin America. J Dev Stud 45(1):76–95

Brander JA, Dowrick S (1994) The role of fertility and population in economic growth: empirical results from aggregate cross-National Data. J Popul Econ 7(1):1–25

Chew J (2016) These Are the Most Corrupt Countries in the World http://fortune.com/2016/01/27/transparency-corruption-index/

Collier P, Hoeffler A (1998) On economic causes of civil war. Oxf Econ Pap 50(4):563–573

Collier P (2000) Ethnicity, politics, and economic performance. Econ Polit 12(3):225–245

Collier P (2001) Ethnic diversity: an economic analysis. Econ Policy 32:129–166

Davoodi HR, Tanzi V (1997) Corruption, public investment, and growth. IMF Work Pap 97(139):1–23

Dawson JW (2003) Causality in the freedom-growth relationship. Eur J Polit Econ 19(3):479–495

De Haan J, Siermann CLJ (1995) A sensitivity analysis of the impact of democracy on economic growth. Empir Econ 20(2):197–215

De Haan J, Siermann CLJ (1996) New evidence on the relationship between democracy and economic growth. Public Choice 86(1):175–198

Desmet K, Ortuno-Ortin I, Wacziarg R (2015) Culture, ethnicity and diversity. NBER working paper no. 20989. National Bureau of economic research. Cambridge

Easterly W, Levine R (1997) Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ 112(4):1203–1250

Easterly W (2001) Can institutions resolve ethnic conflict? Econ Dev Cult Chang 49(4):687–706

Esteban J, Ray D (1994) On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica 62(4):819–851

Goren E (2014) How ethnic diversity affects economic growth. World Dev 59:275–297

Kimenyi MS (2006) Ethnicity, governance and the provision of public goods. J Afr Econ 15(1):62–99

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny R (1999) The quality of government. J Law, Econ Org 15(1):222–279

Levine R, Renelt D (1992) A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. Am Econ Rev 82(4):942–963

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110:681–712

Mo PH, Papyrakis E (2014) Fractionalization, polarization, and economic growth: identifying the transmission channels. Econ Inq 52(3):1204–1218

Montalvo JG, Reynal-Querol M (2005) Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. Am Econ Rev 95(3):796–816

Mulligan CB, Gil R, Sala-i-Martin X (2004) Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? J Econ Perspect 18(1):51–74

Nelson RR, Phelps ES (1966) Investment in Humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. Am Econ Rev 56(1/2):69–75

Piatek D, Szarzec K, Pilc M (2013) Economic freedom, democracy, and economic growth: a causal investigation in transition countries. Post-Communist Econ 25(3):267–288

Ranis G (2009) Diversity of communities and economic development. Yale Univ Econ Growth Center 977:1–17

Reynal-Querol M (2002) Ethnicity, political systems, and civil wars. J Confl Resolut 46(1):29–54

Roe J, Siegel J (2011) Political instability: effects on financial development, roots in the severity of economic inequality. J Comp Econ 39(3):279–309

Sasaoka Y (2007) Decentralization and conflict. Japanese International Cooperation Agency, 889th Wilton Park conference, pp 1–30

Transparency International (2015) Corruption Perception Index 2015. http://www.transparency.org/cpi2015. Accessed July 2016

World Bank (2016a) Anti-Corruption http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance/brief/anti-corruption. Accessed July 2016

World Bank (2016b) Poverty: Overview http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview. Accessed July 2016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

The 2SLS model was run for the full sample of countries, both with and without the Gini index. The results in the body of the paper excluded the Gini Index. When including the Gini index, the sample only consisted of 754 observations, compared to 1791 observations when excluding the Gini index. When run with the Gini, corruption is found to affect instability, but neither measure of fractionalization nor the Gini index is significant. Religious fractionalization significantly impacts GDP growth, only at the 10% level, and neither political instability nor the Gini index has a significant impact on GDP growth. This does not agree with the findings in the literature. The inclusion of the Gini index may be impacting results as it dramatically lowers the sample size (Tables 4 and 5).

Appendix 2

This appendix contains results with both additional variables and another empirical methodology. A country’s openness to international trade may have a significant impact on its economic growth (Ades and Glaeser 1999; Alesina et al. 2000). In order to test the impact of these factors and to check robustness of the other results, analyses including openness is included in the tables below. These tables include a variable for openness (trade/GDP). The tables below also include a variable representing economic freedom. Tables 6 and 7 contain results using the fixed effect methodology in the body of the paper with these additional variables. An interaction term for openness and initial GDP per capita was also tested but was insignificant so not included in the results. Tables 8 and 9 test these additional variables using a GMM methodology. One of the weaknesses of a 2SLS or similar type of regression analysis is its reliance on functional form. As an additional test of robustness, a generalized method of moments (GMM) methodology is employed on the data. Its usage in this case helps to show that the results are not contingent to specific assumptions regarding functional form.

There is some loss of observations when adding the additional variables. These additional analyses have 1553 observations as opposed to the 1791 observation from the results in the body of the paper. It is worth noting a few differences in the results. One substantial difference in the fixed effects analyses is corruption having a positive direct impact on economic growth. This was consistent with some of the subsample analysis but not with the 1791 observation full sample results (in which corruption’s direct effect was insignificant). For the GMM analysis, the direct impact of corruption on economic growth was insignificant. A relevant difference in the GMM results is the significant, positive effect of instability on economic growth. This occurs in the 1553 observation sample run with GMM. However, instability becomes insignificant if GMM is run with the full 1791 observation sample.Footnote 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karnane, P., Quinn, M.A. Political instability, ethnic fractionalization and economic growth. Int Econ Econ Policy 16, 435–461 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0393-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0393-3