Abstract

Natural experiments are an important alternative to observational and econometric studies. This paper provides a review of results from empirical studies of alcohol policy interventions in five countries: Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong, Sweden, and Switzerland. Major policy changes were removal of quotas on travelers’ tax-free imports and reductions in alcohol taxes. A total of 29 primary articles are reviewed, which contain 35 sets of results for alcohol consumption by various subpopulations and time periods. For each country, the review summarizes and examines: (1) history of tax/quota policy interventions and price changes; (2) graphical trends for alcohol consumption and liver disease mortality; and (3) empirical results for policy effects on alcohol consumption and drinking patterns. We also compare cross-country results for three select outcomes—binge drinking, alcohol consumption by youth and young adults, and heavy consumption by older adults. Overall, we find a lack of consistent results for consumption both within- and across-countries, with a general finding that alcohol tax interventions had selective, rather than broad, impacts on subpopulations and drinking patterns. Policy implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research on alcohol policy faces the problem that causality is likely to work in both directions—from policy to outcomes and from outcomes to policy. For example, econometric studies of alcohol taxes are limited by the fact that tax rates may be set endogenously as a response to alcohol-related harms or other economic and political variables, rather than vice versa [1–3]. Subsequent changes in alcohol consumption and behaviors result in uncertain data-generating processes and complicate causal interpretation of results, especially for aggregate state or national data. Regression analyses that treat the problem as a simple cause-and-effect from policy to outcomes will suffer from endogeneity bias [4]. Also, many tax changes are small in magnitude, limiting possible responses by consumers. Given these and other problems inherent in observational studies, an alternative identification strategy is to seek circumstances where a substantial change is imposed externally by forces beyond control of local alcohol policymakers. Natural or quasi-experiments are circumstances that mimic a randomized trial, wherein a policy intervention is imposed on a well-identified subpopulation and there also is an absence of change for a similar subpopulation or control group. Further, interventions are of sufficient magnitude that behavior is likely to be affected. One strength of natural experiments is that non-policy determinants of alcohol consumption and related harms—such as income, urbanization, and demographics—are reasonably assumed to be constant, at least in the short run. Hence, identification of a causal effect for alcohol policy and its potential magnitude should be relatively straightforward.

A review of empirical results from natural experiments fills an important gap for evidence-based alcohol policy. Several previous literature reviews include only a few relevant studies of natural experiments, especially studies published prior to 2008, whereas most studies examined here were published from 2008 to 2014. A literature review by Elder et al. [5] included two studies for Switzerland. A review by Patra et al. [6] included three studies for Switzerland and five Nordic studies. An analysis of alcohol-related harms by Wagenaar et al. [7] included only three studies for Finland. There also are a number of earlier reviews and commentaries that incorporate results from the Nordic Tax Study, including summaries by Ramstedt [8, 9], Room et al. [10, 11], and Rossow et al. [12], but these reviews also provide more limited results and comparisons.

This study conducts a comprehensive review of research results stemming from natural experiments for alcohol policy interventions in five countries: Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong, Sweden, and Switzerland. In three Nordic countries, economic and physical interventions that approximate natural experiments are: (1) removal of quotas on travelers’ tax-free alcohol imports from European Union (EU) countries (effective January 2004); (2) substantial tax reductions in Denmark in anticipation of imports from Germany (October 2003 and January 2005); and (3) substantial tax reductions in Finland in anticipation of Estonia joining the EU (March 2004). Because parts of Sweden are adjacent to Denmark, it was expected that quota and tax changes would have differential effects, with greater impacts in southern Sweden. Hence, northern Sweden is used as a control site in many Nordic studies. In Hong Kong, as a response to an economic recession, wholesale duties on imported wine and beer were cut in half in 2007 and subsequently eliminated in 2008. By 2012, Hong Kong was the largest wine auction and distribution center in the world [13]. In Switzerland, an agreement with the World Trade Organization resulted in an elimination of discriminatory duties on foreign spirits effective July 1999, leading to significant reductions in retail prices of foreign spirits. The number of importers also was increased.

Using these interventions, numerous research studies focus on before–after changes in outcomes for alcohol consumption, imports, and alcohol-related harms. For this review, a total of 59 relevant papers were identified based on a systematic search of alcohol literatures. Our focus here is on empirical results for five countries for alcohol consumption and drinking patterns, both positive and negative/null results. Alcohol-related harms for these and additional countries are covered in a separate paper [14]. In the present paper, we analyze the extent to which major policy interventions resulted in changes in drinking and drinking patterns. More generally, we assess the extent to which empirical results for five countries provide a consistent set of findings and evidence-base for future policy.

Methods

Literature search

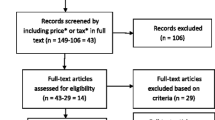

We conducted a systematic search designed to identify scholarly articles with empirical results for policy interventions described above.Footnote 1 Three main sources were searched: PubMed; IARD Research Database (http://www.drinksresearch.org); and the AMPHORA project (http://amphoraproject.net/). We used the latter source to identify European policy changes, while web-based searches were used for other countries for policy-related studies. Advanced searches were conducted using various combinations of a country’s name and title/abstract keywords for alcohol/spirits/beer/wine price* OR tax* OR import* OR policy*, where * is a truncation indicator to include all forms of a root word. Given dates of initial policy changes, searches were limited to articles in the English language published from 2003 to 2014 for Nordic studies and shorter or longer periods for Hong Kong and Switzerland. We screened abstracts to limit articles to those with empirical results that post-date initial policy changes for each country: 2003 for Nordic countries; 1998 for Switzerland; and 2006 for Hong Kong. In cases where screenings were not clear, copies were obtained and final decisions were based on a reading of each article. For the most part, excluded articles discuss broader aspects of alcohol policy or contain empirical results covering earlier policy changes and time periods. No studies were omitted for quality reasons, but in several cases there are data or method issues that require comment. Restricting results to English-language articles is not a major limitation as many articles in Nordic languages are preliminary results that are summarized or examined elsewhere in English (e.g., [11]). Both authors read the articles and together finalized the summaries. Data were collected on the following items: policy interventions analyzed; outcomes examined; data type and sample sizes; subpopulations (age, gender, etc.); time periods examined; measurements for alcohol use; and statistical methods. Note was taken of significant positive results for maintained hypotheses at a 95 % confidence level and any contrary results (i.e., significant negative or null results).

Policy interventions

Policy interventions analyzed in primary studies are summarized in Table 1. In all cases there are two or more policy changes occurring within a short time span, such as Denmark with tax cuts in late 2003 and 2005, import quotas from EU countries removed in early 2004, and minimum age increased in 2004. Although most interventions operate in the same direction (lower taxes and prices, increased availability), results from experiments are complicated by near simultaneous changes in several policy variables that can have differential effects. This reflects a tendency for alcohol policy to operate in several dimensions simultaneously, and might be seen as an important limitation for systematic reviews. A few studies report separate results for time-dependent interventions [23–25]. Further, there are effects possible by beverage due to significant differences in portability and tax/price changes, e.g., larger tax reductions for spirits. Policy interventions that are not uniform raise issues of substitution among beverages vs. additions to total alcohol consumption. Several studies comment on this policy issue [13, 26, 27, 28]. Finally, this review is concerned with changes in alcohol behaviors arising from policy interventions, and not more-or-less stable cross-sectional predictors that drive differences within and across countries. For example, it is well known that consumption levels are higher in Denmark compared with its Nordic neighbors and heavy drinking is an issue in Finland. It is changes in consumption or changes in heavy drinking that studies of natural experiments are designed to illuminate.

Overall, price reductions in the five countries are greater in Finland and greater for spirits compared to beer and wine, except in Hong Kong. Relative beverage shares affected directly by tax changes are approximately: Denmark, 100 %; Finland, 100 %; Hong Kong, 55 % (imported wine and beer); Sweden, 17.5 % (spirits); and Switzerland, 8 % (imported spirits). With these limitations in mind, the major price and availability changes analyzed in primary studies are summarized as follows:

-

Denmark—large reduction in Danish spirits tax (45 %) in late 2003 and large increase in EU travelers’ allowances in early 2004. Spirits prices for cheaper brands fell by 25 % [28, p. 181]. More modest tax reductions (13 %) for beer and wine occurred in 2005. Estimated beverage shares in 2003 and 2010 are: beer, 47 and 38 %; wine, 39 and 48 %; and spirits, 14 and 14 % [38].

-

Finland—large reductions in alcohol taxes in early 2004 for spirits (44 %) and beer (32 %), resulting in average off-premise price reductions of 33 % for spirits and 13 % for beer [31, p. 286]. A smaller tax reduction for table wine of 10 %. A large increase in EU travelers’ allowances occurred in January 2004, which was effective when Estonia joined the EU in May 2004. The change in EU travelers’ allowances was more important in Finland compared with its Nordic neighbors [39, p. 27]. Tax increases occurred in 2008–2009. Estimated beverage shares in 2003 and 2010 are: beer, 47 and 46 %; wine, 15.5 and 17.5 %; spirits, 25.5 and 24 %; and other, 12 and 12.5 % [38].

-

Hong Kong—wholesale duties reduced by 50 % on imported wine and beer, and all other alcohol beverages except spirits, effective March 2007. All duties were eliminated in February 2008, except spirits. Price reductions were about 14 % for “foreign-style” wines, but only 2 % for beer [13, p. 721]. Spirits prices also rose [32]. Estimated beverage shares in 2006 and 2010 are: imported beer, 42 and 38 %, imported wine, 13 and 23 %; and imported spirits, 36 and 31 % ([32], Table 3).

-

Sweden –Sweden made several gradual adjustments to pending EU rules on cross-border trade. During 2002–2003, quotas were relaxed and effectively removed in early 2004 [9, p. 414; 17]. A large reduction in Danish spirits’ tax occurred in late 2003. Swedish retail prices for alcohol beverages rose somewhat less than the general price index for 2000–2010. Estimated beverage shares in 2003 and 2010 are: beer, 40.5 and 37 %; wine, 42 and 47 %; spirits, 17.5 and 15 %; and other, 0 and 1 % [38].

-

Switzerland—substantial reduction in import duties on foreign spirits in 1999 (–12 to –50 %), resulting in a 30–50 % reduction in retail prices for foreign spirits [40, p. 267]. The number of importers also was increased. Estimated beverage shares in 2000 and 2010 are: beer, 30 and 32 %; wine, 52 and 49 %; spirits, 17 and 18 %; and other, 1 and 1 % [38]. About half of all spirits sales in Switzerland are foreign imports [40, p 267], suggesting that only 8–10 % of the market was directly affected by the price change.

Results by country for alcohol consumption and drinking patterns

Description of primary studies

Searches using PubMed returned 92 articles, while IARD searches returned 88 articles. Adding studies obtained from article-level references, a total of 149 primary articles were examined for relevant results with 59 articles selected for review for consumption or harms (a list of 90 excluded articles is available upon request). Several of 59 studies cover more than one country [11, 28, 23, 39]. For alcohol consumption and drinking patterns, we recovered 29 studies containing a total of 35 results divided as follows: Denmark (6 results); Finland (9); Hong Kong (2); Sweden (13); and Switzerland (5). Data samples include special random surveys (e.g., Nordic Tax Study surveys); on-going formal surveys; census registry data; and school surveys. Tabular summaries are grouped by type of data used in each primary study, which divides the studies according to target populations. Depending on the survey and time periods, sample sizes vary from modest numbers in the 1–5000 range (e.g., [11, 13, 41, 40] to large samples with 40–100,000 respondents [25, 42]. Subpopulations by age include legal-age individuals (ages 16 or 18 years and older); young adults (16–29 years); underage youth (<16 or 18 years); and older adults (>44 years). Consumption by older adults is a special focus in Nordic studies due to propensity to import and connections with chronic alcohol-related harms. Northern Sweden is used as a control site in several Nordic studies, but this feature is absent in primary studies for Hong Kong and Switzerland. Alcohol consumption in surveys is often measured as total units of pure alcohol based on beverage-specific quantity-frequency questions. Consumption of specific beverages also is important, given differential policy interventions (e.g., spirits in Denmark). A variety of statistical methods are applied in primary studies, but a basic method is comparisons of before–after averages, with data divided into categories for age, gender, socioeconomic status, beverage, initial drinking-level or pattern, control site, and so forth. In some studies, hundreds of comparisons are possible [43, 34]. In what follows, we first organize results by country, and present within-country summaries for drinking and drinking patterns. This is followed by cross-country results for three select outcomes. For each study and outcome category, we report positive results (statistically significant at 95 % level, p < 0.05) and any negative or null results.

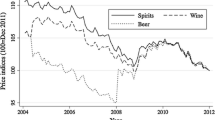

Each country-level presentation includes a graph for pure alcohol consumption per capita (ages 15+) and estimates of liver disease mortality for males (age-standardized rate). Both series are indexed to 100 for the year prior to initial policy interventions. Graphs, as well as some studies, provide a longer-run picture of alcohol control efforts, since liver disease (“cirrhosis”) mortality is an indicator of chronic heavy drinking. We also comment selectively on consumption of individual beverages and unregistered consumption. For Nordic countries, the consumption source is Nordic Alcohol Statistics [44, 45], including estimates of unregistered consumption for 2003–2010. Swiss consumption data are from World Health Organization (WHO), Global Alcohol Database [38] for 1996–2010. Nordic and Swiss mortality data are from EU, EuroStat [46]. For Hong Kong, consumption data are from a Department of Health web site [32], and estimates for age-standardized deaths for 2004–2011 are from a report for the Open Philanthropy Project [47].

Results for Denmark

Figure 1 shows trends for alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality in Denmark. The two data series follow similar time trends. After policy interventions in 2003–2005, total consumption increased by 5 % in 2006, but thereafter declined slightly. Consumption in 2003 was 11.6 l of pure alcohol compared to 11.3 l per capita in 2010. Consumption of distilled spirits rose in 2004, but then remained steady [44]. A decline in consumption of beer was offset partly by increased consumption of wine. Unregistered consumption accounted for 9 % of total consumption in 2008–2010 compared to 15 % for 2003–2005 [38]. Mortality due to liver disease among males peaked in 1997 at 25.4 deaths per 100,000 persons [46]. During 1997–2003, mortality declined by 9 % and has remained at roughly the same level since 2003. Empirical results for Denmark for alcohol consumption and drinking patterns are presented in Table 2.

Six studies analyze changes in Danish consumption, with selected results by age, gender, socioeconomic status, initial drinking level, beverage, and time period. Grittner et al. [26, 48] and Mäkelä et al. [28] provide summaries of Nordic Tax Study (NTS) survey data for 2003–2006. Mäkelä et al. [28, p. 182] report that recorded purchases of spirits rose by 16 % from 2003 to 2004 but total alcohol sales fell by 2 %, suggesting short-run substitution or drinking-level saturation.Footnote 2 In NTS survey data for 2003–2004, there is no sign of increases in alcohol or spirits consumption among either men or women, and use of spirits fell significantly among younger persons aged 16–29 years. Cross-sectional results show increases for consumption only for older persons aged 50–69 years. There is no indication that heavy drinkers increase their consumption more, or decrease it less [28, p. 186]. Grittner et al. [26] extend the NTS data to 2006, yielding four cross sections and a panel sample of 634 persons interviewed at all four time points. In time-trend models for interventions, panel samples show statistically significant negative trends for all persons, all women, younger women, and middle-aged women (30–49 years). Consumption by men remains stable, but older women show some increase in spirits consumption. Multivariate panel regressions yield uniform and statistically significant negative time trends, while cross-sectional regressions yield insignificant time effects for consumption by both men and women. The authors conclude that no relevant changes in drinking behavior are apparent [26, p. 222], suggesting that substitution rather than increased consumption occurred as prices fell. Using NTS data for 2003–2005, Ripatti and Mäkelä [39] model dependence between initial drinking levels and changes in consumption, controlling for regression-to-the-mean (RTM). They find no evidence of differential changes by initial level of consumption for light or heavy drinkers. Further, Room et al. [11, p. 79] comment that any positive effect in the spirits market was dissipated after 2 years. They attribute short-run effects to a “charm of novelty” associated with liberalized travelers’ allowances. Lastly, a study by Andersen et al. [29] uses school surveys for 1988–2010 to analyze trends in weekly use of beer, wine, and spirits among grade-9 students (15-years olds). They report that proportions of students who drank any kind of alcohol increased from 1991 to 2002. However, from 2002 to 2010, drinking prevalence falls and declines are significantly negative for all beverages, except wine drinking by boys. Summary data for 13-year-old boys also indicate a decrease in drinking prevalence.

Denmark made major changes in alcohol policy in 2003–2005 that reduced prices, especially on spirits, and increased availability. Contrary to expectations, consumption declined modestly from 2003 to 2010. Intervention studies in Table 2 suggest that any positive effects were largely temporary, reflecting substitution, novelty, saturation or other social trends by age, gender, or beverage. Some older persons may have increased consumption after 2004, especially older women (>49 years).

Results for Finland

Figure 2 displays trends in Finland for pure alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality. After 2003, consumption rose by about 11 %, with a slight decline after 2007. Total consumption per capita was 11.3 l in 2003 and 12.0 l in 2010. Unregistered consumption was 17.7 % of the total in 2003, rose to 21 % in 2004–2005, and averaged 18 % during 2006–2010 [44]. Male mortality rose dramatically by 52 % during 2004–2007 and then stabilized. Mortality rates per 100,000 were 22.8 in 2003, 34.7 in 2007, and 33.6 in 2010. Liver disease mortality in Finland contrasts sharply with negative trends in most other countries of Western Europe [49]. Empirical results for alcohol consumption and drinking patterns in Finland are presented in Table 3.

There are eight studies for adults in Table 3 for tax-quota policy interventions occurring in 2004. Data samples are divided as follows: three studies use NTS self-surveys for 2003–2005 [28, 39, 50]; two studies use other on-going surveys for adults [31, 25]; two studies employ combinations of self-survey and register data [11, 51]; and one study uses aggregate register data [24]. Much has been made of the fact that register data for Finland show increases in alcohol use for 2004–2007, whereas NTS surveys show only selective increases in consumption and no change overall [11, 28]. Three NTS studies report null results as follows: (1) Mäkelä et al. [28, p. 185] finds that the volume of total alcohol use declines significantly in panel data for all persons, men only, and younger respondents (16–29 years), and spirits consumption did not change for men, women, or heavier drinkers; (2) Mustonen et al. [50, p. 517] report no significant changes in abstinence or frequency of drinking, and men and women report less binge drinking in 2005 compared with 2003, while positive changes are a small rise in total alcohol and spirits consumption by middle-aged men (30–49 years) and younger women; and (3) Ripatti and Mäkelä [39, p. 27] use a panel sample for 2003–2005 for individuals who reported drinking alcohol in all 3 years. Correcting for RTM, they report a decrease in overall consumption and no change in consumption among heavy drinkers. Sample sizes in these studies vary from about 1100–1300 respondents in [28] to 2400 in [39, 50].

Two other studies use large on-going surveys for Finnish adults. Results in Helakorpi et al. [31] for 2004–2008 show an increase in moderate-to-heavy consumption among middle-aged and older persons (45–64 years), but no increases among younger men or women. Binge drinking by men did not increase significantly, except among those with low-education attainment. Among women, binge drinking increases for all age groups, except for ages 35–44 years, and increases are stronger among women with higher education. The authors comment that for policy changes, different drinking consequences can occur with results varying by subpopulation [31, p. 291]. Rossow et al. [52, p. 1449] report an increase in consumption and heavy drinking among both men and women during 2000–2008 based on drinking habit surveys carried out by Statistics Finland. However, over the longer-run, there is a convergence of men’s and women’s drinking patterns, with a decline for men in the proportion of drinking occasions with intoxication [53]. Several studies contrast results for survey and register data. Using register data, Mäkelä and Österberg [51] show that recorded consumption rose by 7 % in 2004 compared with 2003, and total consumption (recorded plus unrecorded) increased by 10 %. Unrecorded consumption rose in 2004–2005, but decreased in 2006. They also report that youth health surveys show a downward trend in drinking frequency and binge drinking after 2004. They note that this finding contrasts with earlier econometric results indicating greater price sensitivity among youth [51, p. 561]. Room et al. [11] put these data to a similar test. They argue that NTS data did not show a general increase in consumption, except for selective increases among those over the age of 45 years or with less education. However, register data indicate increased consumption, suggesting that policy interventions may have strengthened pre-existing trends [11, p. 84]. Allamani et al. [23, 24] employ aggregate data for 1958–2011. Their multivariate analysis for Finland indicates that lower taxes in 2004 did not lead to an increase in recorded alcohol consumption, but this ignores possible policy effects on unregistered consumption.

Lastly, Lintonen et al. [25] use a large nationwide adolescent health survey and report mixed results based on two types of statistical tests: cross-tabulations with Chi square tests; and regression models that include time, time-squared, and binary indicator variables for policy changes. Separate results are reported for six age/gender groups for 1981–2011. Using cross-tabs for the period 2003–2005, there are significant decreases in monthly drinking among 14- and 16-year-old girls, and 14-year-old boys [25, p. 622]. In regression models, significant decreases are observed for both 14-year-old boys and girls. Monthly drunkenness decreases among 14- and 16-year-old girls using both tests [25, p. 623]. Finnish alcohol policy began to tighten after 2006, but mixed results are again reported. Cross-tabs for 2005–2011 indicate a decrease in monthly alcohol use among 14- and 16-year-old boys and girls, but regression models show a significant increase for 14-year-old girls and 16-year-old boys [25, p. 623]. Monthly drunkenness decreases among 14- and 16-year-old boys (cross-tabs), but the regression model yields an increase for 14-year-old boys. Many findings in this study are contrary to expectations and the authors conclude that adolescent drinking was not affected by 2004 interventions [25, p. 625].

Overall, consumption results for Finland are mixed. Results from NAS surveys [28, 39, 50] show little change in adult drinking behavior, but other health surveys [31, 52] suggest that moderate-to-heavy drinking increased among older adults. Heavy-drinking individuals, especially older adults (>45 years), may have increased imports of alcohol, at least in the short run [16]. Lower-income younger persons and youth were not affected by tax-quota policy interventions [28, 31, 25, 51]. A particular policy concern in Finland is the increase in moderate to heavy consumption by those over 45 years, which is reflected in the mortality series in Fig. 2. As noted by Helakorpi et al. [31, p. 291], pronounced differences according to subpopulation can result from a given policy change. Further, NAS survey results for alcohol consumption do not agree with changes in aggregate register data for Finland. Room et al. [11, p. 85] comment that this may reflect small changes in consumption levels and possible sampling biases. They give priority to register data as a more reliable source.

Results for Hong Kong

Figure 3 shows trends in Hong Kong for alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality for the time period 2004 to 2011. Per capita consumption rose by 10 % from 2006 to 2008, and then stabilized. Consumption of pure alcohol was 2.54 l per capita in 2006 compared to 2.62 l in 2010, which is well below other Asian countries such as mainland China, Japan, and Korea. However, wine consumption increased sharply, accounting for only 13 % of consumption in 2006 and 23 % in 2010. The policy change created a market environment that removed all duties on alcohol except spirits [54]. An index for male mortality declined after 2006, and does not reflect increases in consumption. Results for Hong Kong are in Table 4.

Two studies present results for alcohol consumption and drinking patterns, given policy changes in 2007 and 2008. Chung et al. [13] conducted telephone surveys of Chinese residents (18–70 years) in 2006, 2011, and 2012. Prevalence of ever-drinking alcohol increases from 67 % in 2006 to 85 % in 2012. Respondents who reported any past-year drinking also increased. Quantity of alcohol consumed did not change, but prevalence of binge drinking declined significantly [13, p. 4]. Using survey data for 2010 and 2011, Kim et al. [33, p. 1220] report no change in the proportion of weekly drinkers, while prevalence of past-month binge drinking declined. Hence, two empirical studies in Table 4 report little or no change in drinking behaviors, except for increased prevalence of ever-drinking. Binge drinking, which is uncommon in Hong Kong, declined after 2006, although some selective increases occurred. A main effect of duty reductions was an increase in social drinking as evidenced by wine consumption [55, p. 514].

Results for Sweden

Figure 4 displays trends in Sweden for pure alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality. Alcohol use declined steadily from 2004 to 2010. Consumption of pure alcohol was 10.2 l per capita in 2003 and 9.5 l in 2010, a decline of 7 %. Unregistered consumption was 32 % of the total in 2003, rose to 37 % in 2004–2005, and averaged 27 % for 2006–2010 [44]. Deaths from liver disease declined after 2005, and the death rate in 2010 was 10 % below the rate in 2003. Empirical results for Sweden are presented in Table 5.

There are 13 studies in Table 5, but only a few provide positive or mixed evidence for select increases in alcohol consumption. According to Ramstedt [9, p. 410], total consumption peaked in 2004 and subsequently declined. Short-term rises were greatest for wine and strong beer. From 2004 to 2009, consumption declined by 11 %, with larger decreases for spirits. Ripatti and Mäkelä [39, p. 28] use NTS data for 2003–2005 for individuals reporting drinking in all 3 years. Correcting for RTM, these data indicate an increase in consumption for moderate drinkers in southern Sweden, but reductions for heavy drinkers. Using survey data, six studies provide mostly negative or null results for Swedish adults. For example, Gustafsson [43] uses NTS samples for 2003–2006, which show no significant increases for all persons or men-only samples, and statistically significant reductions in alcohol use among younger women, women-only samples, younger binge drinkers, and younger heavy drinkers. Similar negative or null results are found in Mäkelä et al. [28], Raninen et al. [56], Ripatti and Mäkelä [39], and Room et al. [11]. A study by Stafström and Östergren [57] uses self-report surveys conducted in 1999 and 2005 for Scania County in southern Sweden. Deregulation of cross-border trade did not increase total alcohol consumption. Significant declines are found for several groups, including men, high-volume men and women, unemployed men, single men, and single women. Some increases are noted for low- and moderate-volume drinkers, but this might be explained by sampling biases or RTM as individual drinking patterns fluctuated considerably over time [57, p. 575].

Two studies for youth provide evidence for increased alcohol use after 2004. Hallgren et al. [42, p. 584] analyze a large sample based on repeated cross sections for Stockholm students in grade 9 (15–16 years) and grade 11 (17–18 years) between 2000 and 2010. They show that consumption increased only among heaviest drinkers (top 5–10 %) for grade-9 males, grade-11 males, and grade-11 females. Prevalence of abstainers increases steadily over time and binge drinking declines among lighter drinkers, but bingeing increases for heaviest drinkers and grade-11 females [42, p. 587]. However, a study by Stafström [60] analyzes two data sets collected in 2003 and 2005 for grade-11 students in southern Sweden. He finds a significant increase in binge drinking. Prevalence of drinking is stable over time, but proportion of respondents who had ever been intoxicated declines [60, p. 582]. Four other studies provide mostly negative or null results for youth drinking in Sweden. For example, Norström and Svensson [41, p. 1440] analyze survey data for grade-9 students for 2000–2012 and report substantial declines in mean alcohol consumption and frequency of binge drinking, and a marked increase in abstainers. Similar results are found in Svensson [61] and Svensson and Landberg [59]. A study by Raninen et al. [58] uses data drawn from a nationally representative sample of grade-11 students for 2004 to 2012. Consumption of alcohol rises for 2004–2006, but this increase is not statistically significant. After 2006, there is a steady and significant decline, and consumption in 2010 among all respondents is 15 % below peak levels. Decreases are observed in all decile groups and changes for boys and girls are roughly the same [58, p. 683].

Numerous studies in Table 5 address issues of alcohol consumption in Sweden following tax cuts in Denmark during 2003–2005 and Swedish import quota interventions during 2002–2004. Unlike the Finnish case, register data for Sweden are consistent with results from NTS surveys. Short-term positive effects on alcohol consumption are mostly limited to moderate- and lighter-drinkers. Gustafsson [34, p. 464] and Bloomfield et al. [35] argue that southern Sweden is now characterized by social drinking, rather than drinking to intoxication. Studies by Hallgren et al. [42] and Stafström [60] found some increases for heavier-drinking youth, but their results are not supported by four other youth studies [41, 58, 61, 59].

Results for Switzerland

Figure 5 displays trends for Swiss alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality. Both series were declining prior to price reductions for foreign spirits in 1999. Declines continued after 1999, but proportional reductions in mortality are somewhat greater. Consumption series show a slight increase in 2000 (plus 2 %) following interventions, but thereafter a 10 % decline in consumption occurs. Consumption in 2010 was 10 l per capita of pure alcohol compared to 11 l in 1999 and 2001. Unregistered consumption is negligible [38]. Only spirits prices were directly affected by policy changes. Spirits were 17 % of sales in 2000 and roughly half of all spirits sales are foreign imports. Liver disease mortality in 2010 was 13.0 deaths per 100,000 compared to a rate in 1996 of 17.7, a 26.5 % decline [46]. Empirical results for Switzerland are presented in Table 6.

Four related studies use survey data collected at four time points during 1999–2001, starting 3 months prior to interventions (March 1999 baseline). Follow-up surveys were conducted in October 1999, March 2000, and October 2001. Studies report results for short-run changes during 3 to 9 months following interventions, while long-run results pertain to changes from 1999 to 2001. Two studies suggest a short-run increase in use of spirits among heavier drinkers [27, 40], but this change is reported as temporary in Gmel et al. [62, p. 39]. Long-run increases in spirits consumption are mainly found for lighter drinkers, especially younger males (<30 years) who were classified as light-drinkers at baseline. Heeb et al. [27, p. 1441] report that binge drinking is insignificant for spirits use, while Kuo et al. [36, p. 723] find binge drinking is important, but time (follow-up year) is insignificant. No results are reported for effects of interventions on prevalence or frequency of binge drinking, but heavier drinkers were not more affected by lower prices. A study by Gmel et al. [62] makes a substantial effort to correct for RTM, and they find that long-term effects are much weaker for heavy drinkers or even negative. Heeb et al. [27, p. 1442] comment that price changes for spirits may not have increased alcohol consumption, as there is a decline in use of other alcohol beverages. Lastly, Allamani et al. [23, p. 1538] report that policy interventions temporarily increased consumption in 2000, but consumption continued its long-term decline after that date. In summary, recorded consumption for Switzerland rose modestly in 2000, but thereafter declined by 10 %. Empirical studies in Table 6 indicate a temporary rise in spirits consumption that is matched somewhat by reductions in use of beer and wine. Price reductions mostly affected younger males and light drinkers, while effects on heavy drinkers were not long lasting [62, p. 32].

Selected results for drinking patterns: cross-country comparisons

In order to further assess results in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, we examine the consistency of findings across countries for three critical groups: binge drinkers; young adults and youth; and heavy-drinking older adults.

Binge drinking

There are 18 studies that present results for binge drinking or intoxication. In 14 of 18 studies, we judge results to be largely negative or null—alcohol policy interventions that reduced prices and increased availability had little or no positive effect on binge drinking and drunkenness. Listed by country, these 14 studies are: Denmark [11, 29]; Finland [11, 25, 51, 50]; Hong Kong [13, 33]; Sweden [11, 43, 41, 61, 59]; and Switzerland [27]. Four remaining studies report mixed results. For example, Helakorpi et al. [31] use a health survey to examine Finnish drinking patterns. For 2004–2008 compared with 2001–2003, binge drinking increases among all women (except ages 35–44 years), and older men (>45 years). Some increases also occur for men with lowest-education attainment and women with high-levels of education. The authors note varying effects by subgroup for policy interventions [31, p. 291]. Similar selective results are reported in Hallgren et al. [42] for Sweden. Stafström [60] reports an increase in binge drinking by Swedish students, but a decline for intoxication. Organized by age group, the results indicate the following: (1) Denmark—binge drinking did not increase for any major adult subgroup [11] and drunkenness declined significantly among 15-year-old boys [29]; (2) Finland—no changes in adult bingeing using NTS data [11, 50] or among youth [25, 51], but selective increases among adults using other survey data [31]; (3) Hong Kong—decline in binge drinking among adults [13, 33]; (4) Sweden—younger binge drinkers reduced alcohol use [11, 43] and bingeing declined generally, with exceptions [42, 41, 60, 61, 59]; and (5) Switzerland—adult binge drinking changed little [27].

Young adult and youth alcohol consumption

There are 18 studies that report results for young adults and youth. Excluding results for binge drinking, there are 10 studies for young adults and eight studies for youth. Overall, these studies contain 14 negative results and only four report positive or mixed results. Three Danish studies report significant declines in alcohol use by young adults for 2003–2004 or 2003–2006 and youth during 2002–2010 [26, 28, 48]. In Finland, three of four studies indicate policy interventions in 2004 did not increase drinking by youth or young adults [28, 25, 51]. The exception is Mustonen et al. [50, p. 518], who report a rise for 2003–2005 in spirits consumption by younger women (ages 15–29 years). Among nine Swedish studies, negative results are found in three studies for young adults and five of six studies for youth [9, 28, 43, 41, 58, 60, 57, 61]. Results in Hallgren et al. [42, p. 586] for Stockholm youth are mixed—only very heavy drinkers increased consumption over time. Finally, two studies for Switzerland [27, 36] provide positive results for spirits drinking by young adults (15–29 years), but long-term effects are confined to lighter drinkers.

Older adults and heavy-drinking older adults

Results for older adults (>44 years) and older heavy-drinking adults are reported in a number of studies. Summarized by country and data type, these results provide insight into economic and cultural differences as well as possible shortcomings of some research methodologies. For Denmark, NTS surveys tend to show some short-run increases in consumption by older men and women following policy changes, but little change when panel data are employed [26, 28, 39, 48]. Differential changes among heavy drinkers are not apparent. Mäkelä et al. [28, p. 189] comment that heavy drinkers might be underrepresented in the surveys or that selective dropouts might affect some results. However, Grittner et al. [48] find that correcting for non-respondents has no effect on NTS-based results. Results for Finland based on NTS data show similar outcomes [11, 28, 39, 50]. However, several Finnish studies [31, 51, 52] using other surveys or register data indicate that heavy drinking increased in Finland among older adults, especially those with lower-levels of education. In Sweden, NTS data again show little variation by age or drinking level [11, 28, 39, 43], and this is supported by other independent surveys [9, 56, 57]. In Switzerland, any positive results are limited to younger male drinkers and lighter-to-moderate drinkers [27, 62, 36]. Overall, with the exception of Finland, policy changes seem to have had little effect on older adults.

Discussion

This paper provides a critical assessment of empirical evidence from 29 studies covering natural experiments in alcohol policy for five countries: Denmark, Finland, Hong Kong, Sweden, and Switzerland. Overall, we find a general lack of consistent results that can provide a sound evidence-base for development of alcohol tax policy. In all countries there is a lack of robust results for major segments of the population, following interventions that reduced prices and relaxed import quotas. Our conclusion parallels concluding statements in several primary studies. For example, a cross-country study by Room et al. [11, p. 82] finds that self-report longitudinal and repeated cross-sectional NTS survey data failed to show “any increase in average volume of consumption or binge drinking for any country, or for major subgroups within countries.” A youth study (ages 12–18 years) by Lintonen et al. [25, p. 625] reports that higher prices in Finland during 2005–2011 were associated with increased consumption by some age/gender groups, but overall effects of policy changes are unclear. In many cases, positive policy effects are short-term in nature or apply to particular groups of individuals or subpopulations (older women, low-educated individuals, grade-11 girls, etc.). What we learn from this review is that alcohol tax and price changes are likely to have selective effects on drinking and drinking patterns, rather than broad population-level effects.

Room et al. [10, p. 573] argue that alcohol policy must look beyond mechanical and technical factors, such as tax rates, and take account of a broader range of social and cultural factors. The results in our review are in general agreement with that position. As pointed out by Allamani et al. [37, p. 1711], similar interventions can have quite different effects depending on context and culture, and this holds true for alcohol taxation as a restrictive policy. Desired outcomes are not guaranteed even if a particular policy has been shown to be effective in the past or in a different country or for a different subpopulation. Future research might therefore focus on critical groups, such as youth and older heavy drinkers, but account carefully for social and cultural variables that additionally or more importantly drive learning behaviors and drinking patterns. Another implication of our findings is that recent micro-simulation modeling efforts and broad policy statements, such as Anderson et al. [63] and OECD [64], are based on assumptions that are incorrect or at least too broad. A price or other policy change that affects only subpopulations, such as older or highly educated women, is not reflected in population-level parameters used in such simulations and policy claims. As noted by Holder [65], complex systems do not always work in a simple linear manner or in standard expected ways. Despite substantial advances in micro-simulation modeling, intervening variables and dynamic feedbacks may still limit the ability of such models to capture overall complexity of price effects on alcohol consumption, drinking patterns, and ultimately alcohol-related harms. This seems especially true when social patterns of alcohol use are deeply ingrained. The price reductions examined in this paper—which vary in magnitude by alcohol beverage—present intriguing examples of contradictions to standard economic theory and challenge alcohol policy researchers to examine other natural experiments in different countries and time settings.

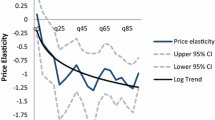

A large body of literature argues that alcohol prices are a highly effective policy tool for addressing issues of alcohol consumption, especially for underage youth, young adults, binge drinkers, and heavy drinkers. Beginning with seminal works by Edwards et al. [66] and Barbor et al. [67, 68], it is widely accepted that alcohol prices (and taxes) effectively target abusive alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms. Although substitution is known to occur, it is argued that net effects of higher prices are positive at the “total population” level. Recent surveys and analyses have sought to extend this evidence base, but in our view these attempts are not always successful. For example, Wagenaar et al. [7] examine alcohol prices or taxes and various categories of alcohol harms. Their statistical tests do not, however, allow for the magnitude of effects. Consequently, what appears as a statistically significant effect may well be unimportant in terms of its economic impact or importance. A meta-regression is required to sort out issues of magnitude, while controlling for heterogeneity, heteroskedasticity, publication bias, and outliers [69, 70]. Results in the present paper provide guidance on possible importance (or unimportance) of intervening covariates affecting heterogeneity of outcomes for alcohol consumption and related harms.

As noted by Babor et al. [68, p. 105], “… studies of what happens when there is a change [i.e., natural experiments] provide the most valuable evidence on the effects of alcohol policy.” In this study, we provided a comprehensive accounting of results from 29 studies that examine five price-related policy changes. While some positive and mixed results are found, our overall conclusion is that the present view on effectiveness of prices and taxes is still open to debate. We do not argue that prices have no effect on alcohol consumption, but rather evidence from five countries tends to support more nuanced effects that depend on time, place, demographics, culture, and so forth. It is of course possible that results from these natural experiments are in some sense not representative. First, Finland and Sweden are possible special cases with long histories of restrictive controls intended to reduce drinking, especially drinking to intoxication, but Denmark represents a Western European pattern of drinking [30]. Drinking and mortality trends in Finland are different as evidenced by register data and liver disease mortality [11, p. 85], but a diversity of evidence is an advantage in a policy context where special circumstances may be important. Hong Kong also may be a special case, with drinking levels that are low relative to Western countries, but it is not that different compared with many developing nations. Second, for the most part policy interventions examined here resulted in reduced prices, and it may be that the demand for alcohol is price inelastic at lower prices only. A “kinked” demand curve is an alternative representation of notions of market “saturation.” However, it is unlikely to be the case that all subpopulations have kinked demands for alcohol at current prices, which complicates modeling and simulation efforts. Third, it also may be that natural experiments are only useful for revealing short-run effects of polices, while overriding cultural trends are dominant in the long run, but not easily understood. Room et al. [10] also argue that incomes and “affordability” play a more important role in determining the range of options for alcohol use, so a strict focus on prices is misleading. All countries represented here are highly developed higher-income nations, with relatively homogenous populations. Moreover, in some cases there clearly are intervening short-run effects such as higher petrol prices in Sweden in 2004 that may have decreased cross-border purchases [11, p. 82]. Fourth, it might be the case that the tax and quota changes analyzed here are simply too small in magnitude to have much impact on consumption, partly due to the fact that price reductions were larger for spirits in four of five cases. Larger or more comprehensive price/tax changes might have greater impacts generally. Finally, while there is considerable methodological variation across studies, there is less independent variation in the underlying data and sampled populations, with many adult and youth studies employing the same or similar data sets (e.g., NTS surveys, CAN surveys, Hong Kong telephone survey, Swiss telephone survey).

Notes

Three of 59 studies focus exclusively on imports [15–17], and are omitted here. Studies for several other countries provide results for alcohol-related harms, e.g., [18–22]; see [14]. We focus here on those natural experiments where a variety of methods are applied to diverse outcomes for consumption and drinking patterns, thus permitting both within- and cross-country comparisons by outcome, subpopulation, time period, etc.

“Short-run” substitution refers to circumstances were the range of alternative substitutes is proscribed to those already known or otherwise permitted. Drinking-level “saturation” as used by Room et al. [11] is the notion that in some “mature” markets, potential demand is satisfied and individuals do not respond much to changes in prices, e.g., my personal demand for toothpaste does not vary. In this situation, substitution occurs mainly in the form of brand switching, including imports and unregistered consumption. Hence, market saturation will be associated with a price elastic demand for alcohol brands and an overall price inelastic demand for total alcohol.

References

Dee, T.: The complementarity of teen smoking and drinking. J. Health Econ. 18, 769–793 (1999)

Kubik, J., Moran, J.: Can policy changes be treated as natural experiments? Evidence from cigarette excise taxes. Working paper 5-2003. Maxwell School, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY (2003)

French, M., Popovici, I.: That instrument is lousy! In search of agreement when using instrumental variables estimation in substance use research. Health Econ. 20, 127–146 (2011)

Angrist, J., Pischke, J.: Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2009)

Elder, R., Lawrence, B., Ferguson, A., et al.: The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am. J. Prev. Med. 38, 217–229 (2010)

Patra, J., Giesbrecht, N., Rehm, J., Bekmuradov, D., Popova, S.: Are alcohol prices and taxes an evidence-based approach to reducing alcohol-related harm and promoting public health and safety? A literature review. Contemp. Drug Probl. 39, 7–48 (2012)

Wagenaar, A., Tobler, A., Komro, K.: Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 100, 2270–2278 (2010)

Ramstedt, M.: Variations in alcohol-related mortality in the Nordic countries after 1995—continuity or change? Nordic. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 24(Supplement), 5–15 (2007)

Ramstedt, M.: Change and stability? Trends in alcohol consumption, harms and policy: Sweden 1990–2010. Nordic Stud. Alcohol Drugs 27, 409–423 (2010)

Room, R., Österberg, E., Ramstedt, M., Rehm, J.: Explaining change and stasis in alcohol consumption. Addict. Res. Theory 17, 562–576 (2009)

Room, R., Bloomfield, K., Grittner, U., et al.: What happened to alcohol consumption and problems in the Nordic countries when alcohol taxes were decreased and borders opened? Int. J. Alcohol Drug Res. 2, 77–87 (2013)

Rossow, I., Mäkelä, P., Österberg, E.: Explanations and implications of concurrent and diverging trends: alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm in the Nordic countries in 1990–2005. Nordic Stud. Alcohol Drugs 24(Supplement), 85–95 (2007)

Chung, V., Yip, B., Griffiths, S., et al.: The impact of cutting alcohol duties on drinking patterns in Hong Kong. Alcohol Alcohol. 48, 720–728 (2013)

Nelson, J., McNall, A.: Alcohol prices, taxes, and alcohol-related harms: a critical review of natural experiments in alcohol policy for nine countries. Health Policy 120, 264–272 (2016)

Grittner, U., Bloomfield, K.: Changes in private alcohol importation after alcohol tax reductions and import allowance increases in Denmark. Nordic Stud. Alcohol Drugs 26, 177–191 (2009)

Grittner, U., Gustafsson, N.-K., Huhtanen, P., et al.: Who are private alcohol importers in the Nordic countries? Nordic Stud. Alcohol Drugs 31, 125–139 (2014)

Ramstedt, M., Gustafsson, N.-K.: Increasing travelers’ allowances in Sweden—how did it affect travellers’ imports and Systembolaget’s sales? Nordic Stud. Alcohol Drugs 26, 165–176 (2009)

Cook, P., Durrance, C.: The virtuous tax: lifesaving and crime-prevention effects of the 1991 federal alcohol-tax increase. J. Health Econ. 32, 261–267 (2013)

Kueng, K., Yakovlev, E.: How persistent are consumption habits? Micro-evidence from Russia. NBER Working Paper 20298. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA (2014)

Maldonado-Molina, M., Wagenaar, A.: Effects of alcohol taxes on alcohol-related mortality in Florida: time-series analyses from 1969 to 2004. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 34, 1915–1921 (2010)

Pridemore, W., Chamlin, M., Kaylen, M., Andreev, E.: The effects of the 2006 Russian Alcohol Policy on alcohol-related mortality: an interrupted time series analysis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 38, 257–266 (2014)

Wagenaar, A., Maldonado-Molina, M., Wagenaar, B.: Effects of alcohol tax increases on alcohol-related disease mortality in Alaska. Am. J. Public Health 99, 1464–1470 (2009)

Allamani, A., Olimpi, N., Pepe, P., Cipriani, F.: Trends in consumption of alcoholic beverages and policy interventions in Europe: an uncertainty “associated” perspective. Subst. Use Misuse 49, 1531–1545 (2014)

Allamani, A., Voller, F., Pepe, P., et al.: Balance of power in alcohol policy. Balance across different groups and as a whole between societal changes and alcohol policy. In: Anderson, P., Braddick, F., Reynolds, J., Bual, A. (eds.) Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA, Chapter 5. European Commission, Alcohol Public Health Research Alliance, Brussels. http://amphoraproject.net/ (2013). Last accessed 18 Nov 2015

Lintonen, T., Karlsson, T., Nevalainen, J., Konu, A.: Alcohol policy changes and trends in adolescent drinking in Finland from 1981 to 2011. Alcohol. Alcohol. 48, 620–626 (2013)

Grittner, U., Gustafsson, N.-K., Bloomfield, K.: Changes in alcohol consumption in Denmark after the tax reduction on spirits. Eur. Addict. Res. 15, 216–223 (2009)

Heeb, J.-L., Gmel, G., Zurbrugg, C., Kuo, M., Rehm, J.: Changes in alcohol consumption following a reduction in the price of spirits: a natural experiment in Switzerland. Addiction 98, 1433–1446 (2003)

Mäkelä, P., Bloomfield, K., Gustafsson, N.-K., Huhtanen, P., Room, R.: Changes in volume of drinking after changes in alcohol taxes and travellers’ allowances: results from a panel study. Addiction 103, 181–191 (2008)

Andersen, A., Rasmussen, M., Bendtsen, P., Due, P., Holstein, B.: Secular trends in alcohol drinking among Danish 15-year-olds: comparable representative samples from 1988 to 2010. J. Res. Adolesc. 24, 748–756 (2013)

Demant, J., Krarup, T.: The structural configurations of alcohol in Denmark: policy, culture, and industry. Contemp. Drug Probl. 40, 259–289 (2013)

Helakorpi, S., Mäkelä, P., Uutela, A.: Alcohol consumption before and after a significant reduction of alcohol prices in 2004 in Finland: were the effects different across population subgroups? Alcohol. Alcohol. 45, 286–292 (2010)

Hong Kong, Department of Health: Change4Health. Last accessed 11 November 2015. http://www.change4health.gov.hk/en/alcohol_aware/figures/alcohol_consumption/index.html (2015)

Kim, J., Wong, A., Goggins, W., Lau, J., Griffiths, S.: Drink driving in Hong Kong: the competing effects of random breath testing and alcohol tax reductions. Addiction 108, 1217–1228 (2013)

Gustafsson, N.-K.: Changes in alcohol availability, price and alcohol-related problems and the collectivity of drinking cultures: what happened in southern and northern Sweden? Alcohol. Alcohol. 45, 456–467 (2010)

Bloomfield, K., Wicki, M., Gustafsson, N.-K., Mäkelä, P., Room, R.: Changes in alcohol-related problems after alcohol policy changes in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drug. 71, 32–40 (2010)

Kuo, M., Heeb, J.-L., Gmel, G., Rehm, J.: Does price matter? The effect of decreased price on spirits consumption in Switzerland. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 27, 720–725 (2003)

Allamani, A., Pepe, P., Baccini, M., Massini, G., Voller, F.: Europe. An analysis of change in the consumption of alcoholic beverages: the interaction among consumption, related harms, contextual factors and alcoholic beverage control policies. Subst. Use Misuse 49, 1692–1715 (2014)

World Health Organization: Global Alcohol Database. Last accessed 18 November 2015. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/?showonly=GISAH&theme=main (2015)

Ripatti, S., Mäkelä, P.: Conditional models accounting for regression to the mean in observational multi-wave panel studies on alcohol consumption. Addiction 103, 24–31 (2008)

Mohler-Kuo, M., Rehm, J., Heeb, J.-L., Gmel, G.: Decreased taxation, spirits consumption and alcohol-related problems in Switzerland. J. Stud. Alcohol 65, 266–273 (2004)

Norström, T., Svensson, J.: The declining trend in Swedish youth drinking: collectivity or polarization? Addiction 109, 1437–1446 (2014)

Hallgren, M., Leifman, H., Andréasson, S.: Drinking less but greater harm: could polarized drinking habits explain the divergence between alcohol consumption and harms among youth? Alcohol. Alcohol. 47, 581–590 (2012)

Gustafsson, N.-K.: Alcohol consumption in southern Sweden after major decreases in Danish spirits taxes and increases in Swedish travellers’ quotas. Eur. Addict. Res. 16, 152–161 (2010)

National Institute for Health and Welfare: Nordic Alcohol Statistics 2011 (Pohjoismainen Alkoholi-tailasto 2011). http://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/104396 (2013). Last accessed 18 Nov. 2015

Østhus, S.: Nordic alcohol statistics 2003–2010. Nordic Stud. Alcohol Drugs 29, 103–113 (2012)

European Union: EuroStat Database. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (2015). Last accessed 18 November 2015

Roodman, D.: The impacts of alcohol taxes: a preliminary review. Open Philanthropy Project. http://davidroodman.com/david/The%20impacts%20of%20alcohol%20taxes%206.pdf (2015). Last accessed 18 Nov 2015

Grittner, U., Gmel, G., Ripatti, S., Bloomfield, K., Wicki, M.: Missing value imputation in longitudinal measures of alcohol consumption. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 20, 50–61 (2011)

Mokdad, A., Lopez, A., Shahraz, A., et al.: Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 12, 145 (2014)

Mustonen, H., Mäkelä, P., Huhtanen, P.: People are buying and importing more alcohol than ever before: where is it all going? Drugs: Education. Prev. Policy 14, 513–527 (2007)

Mäkelä, P., Österberg, E.: Weakening of one more alcohol control pillar: a review of the effects of the alcohol tax cuts in Finland in 2004. Addiction 104, 554–563 (2009)

Rossow, I., Mäkelä, P., Kerr, W.: The collectivity of changes in alcohol consumption revisited. Addiction 109, 1447–1455 (2014)

Härkönen, J., Törrönen, J., Mustonen, H., Mäkelä, P.: Changes in Finnish drinking occasions between 1976 and 2008: the waxing and waning of drinking contexts. Addict. Res. Theory 21, 318–328 (2013)

Yoon, S., Lam, T-H.: The alcohol industry lobby and Hong Kong’s zero wine and beer tax policy. BMC Public Health 12, 717 (2012). http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.1186%2F1471-2458-12-717

Pun, V., Hualiang, L., Kim, J., et al.: Impacts of alcohol duty reductions on cardiovascular mortality among elderly Chinese: a 10-year time series analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 67, 514–518 (2013)

Raninen, J., Leifman, H., Ramstedt, M.: Who is not drinking less in Sweden? An analysis of the decline in consumption for the period 2004–2011. Alcohol. Alcohol. 48, 592–597 (2013)

Stafström, M., Östergren, P.-O.: The impact of policy changes on consumer behaviour and alcohol consumption in Scania, Sweden 1999–2005. Alcohol. Alcohol. 49, 572–578 (2014)

Raninen, J., Livingston, M., Leifman, H.: Declining trends in alcohol consumption among Swedish youth: does the theory of collectivity of drinking cultures apply? Alcohol. Alcohol. 49, 681–686 (2014)

Svensson, J., Landberg, J.: Is youth violence temporally related to alcohol? A time-series analysis of binge drinking, youth violence and total alcohol consumption in Sweden. Alcohol Alcohol. 48, 598–604 (2013)

Stafström, M.: Consequences of an increase in availability due to an eroded national alcohol policy: a study of changes in consumption patterns and experienced alcohol-related harm among 17- to 18-year-olds in southern Sweden, 2003–2005. Contemp. Drug Probl. 34, 575–588 (2007)

Svensson, J.: Alcohol consumption and harm among adolescents in Sweden: is smuggled alcohol more harmful? J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse 21, 167–180 (2012)

Gmel, G., Wicki, M., Rehm, J., Heeb, J.-L.: Estimating regression to the mean and true effects of an intervention in a four-wave panel study. Addiction 103, 32–41 (2008)

Anderson, P., Chisholm, D., Fuhr, D.: Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 373, 2234–2246 (2009)

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: Tackling Harmful Alcohol Use: Economics and Public Health Policy. OECD Publishing, Paris (2015)

Holder, H.: Thoughts on unexpected results and the dynamic system of alcohol use and abuse. Addict. Res. Theory 17, 577–579 (2009)

Edwards, G., Anderson, P., Babor, T., et al.: Alcohol Policy and the Public Good. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1994)

Babor, T., Caetano, R., Casswell, S., et al.: Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity - Research and Public Policy, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2003)

Babor, T., Caetano, R., Casswell, S., et al.: Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity - Research and Public Policy, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2010)

Nelson, J.: Meta-analysis of alcohol price and income elasticities –with corrections for publication bias. Health Economics Review 3, article 17 (2013)

Nelson, J.: Estimating the price elasticity of beer: meta-analysis of data with heterogeneity, dependence, and publication bias. J. Health Econ. 33, 180–187 (2014)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for constructive comments that materially improved the paper. The usual caveats apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Research leading to this paper was supported in part by the International Alliance for Responsible Drinking, Washington, DC, a not-for-profit organization sponsored by major producers of alcohol beverages. This paper presents the work product, findings, viewpoints, and conclusions solely of the authors. Views expressed are not necessarily those of IARD or any of IARD’s sponsoring companies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, J.P., McNall, A.D. What happens to drinking when alcohol policy changes? A review of five natural experiments for alcohol taxes, prices, and availability. Eur J Health Econ 18, 417–434 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0795-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-016-0795-0