Abstract

Background

The determinants of consumer mobility in voluntary health insurance markets providing duplicate cover are not well understood. Consumer mobility can have important implications for competition. Consumers should be price-responsive and be willing to switch insurer in search of the best-value products. Moreover, although theory suggests low-risk consumers are more likely to switch insurer, this process should not be driven by insurers looking to attract low risks.

Methods

This study utilizes data on 320,830 VHI healthcare policies due for renewal between August 2013 and June 2014. At the time of renewal, policyholders were categorized as either ‘switchers’ or ‘stayers’, and policy information was collected for the prior 12 months. Differences between these groups were assessed by means of logistic regression. The ability of Ireland’s risk equalization scheme to account for the relative attractiveness of switchers was also examined.

Results

Policyholders were price sensitive (OR 1.052, p < 0.01), however, price-sensitivity declined with age. Age (OR 0.971; p < 0.01) and hospital utilization (OR 0.977; p < 0.01) were both negatively associated with switching. In line with these findings, switchers were less costly than stayers for the 12 months prior to the switch/renew decision for single person (difference in average cost = €540.64) and multiple-person policies (difference in average cost = €450.74). Some cost differences remain for single-person policies following risk equalization (difference in average cost = €88.12).

Conclusions

Consumers appear price-responsive, which is important for competition provided it is based on correct incentives. Risk equalization payments largely eliminated the profitable status of switchers, although further refinements may be required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Arguments in favor of competition within health insurance markets focus on its welfare-enhancing effects. Particularly, requiring insurers to bear financial risk in addition to the ‘threat of exit’ are designed to promote both productive and allocative efficiency, providing consumers with the products they desire at optimal prices [1]. Consumer mobility is therefore a fundamental component of competitive health insurance markets. However, while the rate of insurer switching is often low [2], this does not a priori mean that health insurance markets are uncompetitive. Indeed high rates of switching may be detrimental. Duijmelinck et al. [3] note that too much switching can result in high administrative costs, while low switching rates have been observed in competitive and non-competitive markets. In this context, no ideal rate of switching exists. More salient for examining consumer mobility and its competitive implications, is understanding who switches, who does not switch, and their motivations for doing so. Particularly important is that consumers display a degree of price-sensitivity and are willing to switch insurer in search of the best-value products. In addition, theory would suggest that low-risk consumers (e.g., young, healthy) are more likely to switch insurer [4]. From a demand-side perspective, this cohort may face lower search and switching costs, while in a community-rated market, they can represent more profitable risks, motivating insurers to focus their resources on attracting them. Heterogeneous switching behavior among groups is not a problem in itself if risk-adjusted payments to insurers, generally organized through risk equalization schemes, can mitigate against the relative attractiveness of more mobile, low risks.

To date, little empirical research has taken place on the determinants of consumer mobility in health systems providing duplicate private health insurance cover. Compared with mandatory insurance systems, consumers in voluntary markets tend to differ in their characteristics [5] while those not happy with their cover also have the option of exiting the market entirely, reverting to the pubic system to provide care. In this context, this study hopes to add to the understanding of the drivers of consumer mobility, including incentives faced by insurers, through analysis of the Irish voluntary private health insurance (PHI) market and its implications for competition. Understanding competitive incentives is especially important given current proposed reforms to predicate Irish healthcare financing on a competing health insurer model [6].

International evidence on consumer mobility

To the extent that switching insurer is a voluntary activityFootnote 1 there are a number of factors that can influence consumer mobility in health insurance markets. The individual decision to switch insurer can be partly understood by weighing up the costs and benefits of switching [1–4]. Particularly, price and quality considerations should influence choice of health insurer. Empirically, price appears to be a strong predictor of switching. Several studies have shown that consumers of health insurance exhibit price-sensitivity. Historically, the majority of this evidence has come from the United States [7–10], however more recently similar effects have been found in certain European (Dutch, German, and Swiss) markets [11–16]. However, price sensitivity in the Dutch system has been found to be comparatively low [11, 17], potentially the result of historically more robust risk equalization, which helps limit price variation between insurers. Price sensitivity has also been shown to vary by risk status, with higher-risk individuals less responsive to changes in price than their low-risk counterparts [9, 18, 19]. Quality has also been shown to influence consumer decision-making. A review by Kolstad and Chernew [20] showed that consumers in the United States were more likely to choose higher-quality plans both with and without the provision of quality-related plan information. Recently, evidence from the Netherlands has shown that consumers were less likely to switch out of higher-quality plans and that those actively searching for health plan information were more likely to switch [16].

The benefits of switching need to be compared against the costs and health insurance markets are generally subject to large search and switching costs. Search costs relate to the costs involved in identifying and interpreting health insurance products and may be incurred numerous times. Although consumer choice is an important predicate of a functioning competitive market, search costs tend to be higher the more product differentiation there is [2]. Switching costs relate to the one-time costs (for example, transaction costs, learning costs, exit costs, see [3]) involved in switching insurer. Switching costs may be subject to behavioral biases that do not reflect rational choice. For example, an endowment effect or status-quo bias may lead to individuals placing an artificially high value on their current insurer [4]. Moreover, search and switching costs tend to be higher for high-risk individuals (e.g., the old and sick) [4]. These groups may have more difficulty navigating the market or may be more concerned about issues around continuity of coverage and therefore less likely to switch. Similarly, there is evidence that better-educated individuals are more likely to switch [16, 21]. Hirschman [22] would also argue that consumers dissatisfied with aspects of their insurance provision may prefer to ‘voice’ their dissatisfaction, rather than taking the more definitive decision to switch to a competitor.

A final strand of literature has considered the association between risk equalization and consumer mobility. In terms of the Dutch system, Van Vliet [23] finds that switchers are good risks in an absolute sense, however, providing risk-adjusted premium subsidies based on health status eliminated predictable profits for this group. A similar conclusion was reached in Germany where more sophisticated risk equalization, based on measures of health status, removed incentives for selection [24].

The Irish PHI market and consumer mobility

Although tax-financed hospital care is available to all residents, 43.9 % avail of PHI [25]. To promote social solidarity, the PHI market is subject to community rating, lifetime cover, and open enrolment regulations. The main benefits of health insurance relate to faster access to hospital care, superior accommodation and a greater selection of providers. Some cover is offered for primary care services, however this is generally subject to large deductibles. Health insurance contracts are generally 12 months in duration at which point consumers have the option to renew, switch insurer, or leave the market entirely. Insurers may impose penalties for switching or cancelling mid-contract. PHI has been available in Ireland since 1957 and was the provision of a single monopolistic insurer, VHI Healthcare (VHI) until market liberalization in the mid-1990 s.Footnote 2 Following liberalization, there was a shift in new and existing consumers, generally the younger and healthier, away from VHI and towards the new market entrants. Compounding this problem and as a result of legal challenges and controversy over risk equalization, the Irish PHI market evolved largely without the allocation of risk-adjusted premium subsidies, making it difficult for the incumbent VHI to compete on price [26]. Strong market segmentation has arisen between the VHI and the newer entrants, undermining the principle of community rating [27]. In 2009, the first risk-adjusted subsidies were introduced, taking the form of age-related tax credits accruing to insurers. These were followed by a bona-fide risk equalization scheme in 2013. Risk-adjusted payments (credits) are based on age, gender, advanced/non-advanced contract statusFootnote 3 and number of inpatient hospital nights. These payments are financed through a community rating levy payable by insurers for each enrollee (see Table 1).

Despite these developments and primarily as a result of limited data availability, to date, little detailed statistical analysis has taken place on consumer mobility within the Irish PHI market. Biennial consumer survey reports published by the market regulator the Health Insurance Authority (HIA) however, highlight a steady increase in the incidence of ever switching insurer, rising from 6 to 23 % between 2002 and 2011, albeit falling back to 20 % in 2013 [28]. Price is considered the most important reason for switching health insurers and its importance has been increasing in recent years. This is most likely a function of the recent Irish economic crisis [29] and significant premium increases over the same period. In 2013, 69 % cited cost savings as the most important reason for switching insurers, up from 50 % in 2007 [28]. Older groups are also more likely to claim that they would not switch [28, 30]. However, there appears be a strong degree of inertia in the market with consumers remaining loyal to their current provider [28].

Data and methods

Data for this study were provided by VHI, the largest insurer in the market.Footnote 4 Over the period August 2013 to June 2014, all policies were flagged at their time of renewal and information was collected for the previous 12 months for each policy. All policies were 12-month contacts. Information on employer-based group health insurance policies is not included in the dataset.Footnote 5 To facilitate analysis, all policies that had changes in cover during their previous 12 months, or added individuals onto a policy, were excluded. This left a final data set of 320,830 policy-level observations. Policyholders were then categorized as either ‘switchers’ or ‘stayers’, with the following definitions:

Switchers

Policyholders, who, at the time of renewal decided to cancel their existing policy and switch to a competitor. Whether a switch to a rival insurer occurred is known based on information provided by the departing policyholder.Footnote 6

Stayers

Stayers are defined as those who, at time of their renewal decision, renewed their subscription with the insurer.

This analysis assesses differences in policy (flag for children on policy, flag for students on policy, duration of cover, maximum cover level, length of hospital stay (LOS), relative premium change, single/multiple policy status and month of renew/switch decision) and consumer (age, gender, marital status and region of residence) characteristics between switchers and stayers for the 12 months leading up to the switch/renew decision. Particularly, it is expected that younger policyholders and those recording lower healthcare utilization will be more inclined to switch. Moreover, price is expected to influence switching propensities, while low-risk individuals are expected to be more price sensitive. These differences are measured by way of a binary logistic regression model with main results presented in terms of odds ratios. This is a standard approach adopted in empirical consumer switching analyses [21, 31–33]. Regression results presented in terms of average marginal effects are contained in the Supplementary material. Cluster robust standard errors are calculated to account for any correlation of errors within plans. As the data are aggregated at the policy level, regression models are analyzed separately for single-person, multiple-person, and total policies. In order to assess whether price sensitivity differs based on risk type, predicted probabilities from the regression analysis are also computed and assessed for different values of relative premium changes and age, and LOS, respectively.

Relative price effects are captured through a premium variable that measures the difference between the percentage change in price of a policy over the 12 months to the switch/renewal decision and the percentage change in the average market premium.Footnote 7 In order to reduce bias, the maximum level of cover of a particular policy is controlled for in the regression analysis. Both the theories of adverse selection and moral hazard would predict that ex post expenditures and utilization will be influenced by the amount of cover [34]. Moreover, in the Irish context, private care can be provided in public as well as private hospitals and therefore, without controlling for level of cover, differences in expenditure/utilization may not accurately reflect differences in health status. Level of cover is categorized based on HIA definitions (see Table 2).

Finally, the impact of Ireland’s age-related tax credit and subsequent risk equalization scheme is examined in terms of their abilities to equalize any cost differentials that exist between stayers and switchers. Differences in average costs between switchers and stayers are calculated based on recorded claims expenditure for the 12 months prior to switching/renewing. Adjustments for tax/risk equalization credits and levies are made based on publicly available data (over the period of analysis) provided by the HIA (Table 1).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. The largest proportion of policyholders were aged 60–69 (20.6 %) while those in the 18–29 year age-group contained the least number of policyholders (4.0 %). There were a higher proportion of male (51.2 %) and non-married (59.4 %) policyholders, respectively. The majority of policies were single-person policies (54.3 %) while children (students) were recorded on 16.3 % (3.8 %) of total policies. The vast majority of policies provided cover up to a semi-private room in a private hospital (76.1 %). On average, VHI premiums increased by 16.7 %, which reflects strong premium inflation in the Irish market in recent years [35]. Average LOS was slightly less than a day.

Regression results

Table 3 reports the results of the logistic regression analysis.Footnote 8 Across all models, age was negatively associated with the decision to switch (OR 0.971***). For total policies, being male (OR 1.108***) and married (OR 1.301***), respectively, increased the odds of switching. These effects were also observed for multiple-person policies (as relating to main policyholder) but not for single-person policies. Having children or students (apart from single-person policies were that individual is a student) on policies did not impact the decision to switch. Nor did the maximum policy cover level. The overall switching rate was 3.8 %, with those on multiple-person policies more likely to switch than those with single-person policies (OR 1.413***). Duration of policy cover (OR 0.97***) and average policy LOS (OR 0.98***) were both negatively associated with switching. Consumers also appeared to be price sensitive. Finally, higher relative premium increases were positively associated with switching (OR 1.05***). Average marginal effects presented in the Supplementary material are consistent with these findings.

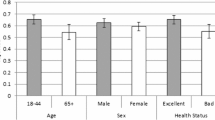

Figure 1a, b examine price effects in more detail. The first point to observe is that both graphs showed a positive relationship between predicted probability of switching and higher relative price increases, consistent with the logistic regression analysis. Similarly, switching was negatively associated with both age in Fig. 1a and LOS in Fig. 1b. Figure 1a also showed that price sensitivity appeared to be strongly associated with age. For example, where the relative price increase was zero, the predicted probability of switching for a 20-year-old policyholder was 6.1 % and this rose to 18.0 % for a 20 % relative price increase. In contrast, for identical relative price effects for an 80-year-old, predicted switching probabilities only increased from 1.1 to 3.9 %. Differential price effects based on LOS were not as noticeable, with large overlap between confidence intervals.

a Predicted probability of switching broken down by different levels of age and relative premium increases for total policies. Error bars indicate 95 % confidence intervals. b Predicted probability of switching broken down by different levels of average LOS [for those admitted to hospital, average LOS was 2.8 days (median = 1 day; interquartile range = 2 days)] and relative premium increases for total policies. Error bars indicate 95 % confidence intervals

Risk equalization payments

Figure 2 graphs the difference in average costs for the 12 months prior to the switch/renew decision between stayers and switchers for different iterations of risk-adjusted subsidies. In absolute terms, the difference in average costs between stayers and switchers was quite large for both single-person (difference in average costs = €540.64; CI €484.37–€596.90) and multiple-person (difference in average costs = €450.74; CI €355.33–€546.15) policies, reflecting the fact that it was low risks who tended to switch. While successive iterations of risk equalization appear to have largely reduced the profitability of switchers, some residual incentives for risk selection may have remained. Particularly, single-person switchers remained profitable following application of risk equalization credits (difference in average costs = €88.12; CI €34.04–€142.20).Footnote 9

Unadjusted and risk-adjusted differentials in average costs (with CI 95 %) between switchers and stayers for single-person and multiple-person policies. Risk-adjusted costs for stayers (switchers) are calculated as actual average cost for stayers (switchers) + average levy paid by stayers (switchers) − the average risk equalization payment attributable to stayers (switchers). Age data were only available for policyholder and spouse (if applicable), therefore it was not possible to include plans with >=2 adults that were not married (approx. 3.1 % of policies). RE Scheme 1 relates to credits and levies applicable between 01/03/2013 and 28/02/2014. RE Scheme 2 relates to credits and levies applicable since 01/03/2014

Discussion

The overall switching rate in this study is quite low,Footnote 10 however, this is similar to recent rates reported in the Netherlands [16, 21] and at the higher end of rates reported in other mandatory health systems [2]. Despite the low level of switching, the motivations and characteristics of those who do switch can provide important insights into the effectiveness of competition.

In this context, price is found to be a strong determinant of switching behavior, as it is in many other markets. Relative premium increases were associated with a higher likelihood of switching. Price responsiveness may be considered an important requirement for proper functioning health insurance markets. As noted by Lako [4], “when price fails to influence consumer switching behavior it can be very frustrating for policy-makers who strive to design health systems that encourage critical consumer behavior”. Evidence would also suggest that younger policyholders are more price sensitive than older policyholders. The finding that longer lengths of VHI cover were negatively associated with switching may point towards a degree of status quo bias in the Irish market. Moreover, switchers appear to be low risk. Switching was negatively associated with age and health status (measured in terms of healthcare utilization). Similar associations have been previously reported [7, 9, 16, 31, 33].

The fact that younger and healthier consumers are thought to face lower switching costs may help explain some of these associations. Furthermore, price competition is beneficial to the extent that it is a product of efficient behavior by insurers. However, these switching dynamics can also be influenced by risk selecting behavior on the part of insurers. For example, poor (or the absence of) risk equalization may incentivize insurers to focus their attention on attracting low (profitable) risks. Furthermore, insurers with a low risk profile may be able to charge lower community-rated premiums than competitors with a higher risk profile and consequently exploit the higher price sensitivity of low risks to further attract favorable risks. In this context, commentators have previously suggested that newer insurers in the Irish market may have engaged in a ‘price-shadowing’ strategy, setting their price marginally below that of the incumbent, VHI, in order to attract a favorable risk profile [26, 27, 36].

Robust risk equalization is therefore need to support community rating and limit incentives for risk selection. However, while successive iterations of risk equalization have reduced cost differentials between stayers and switchers substantially, they have not been eliminated completely. Further improvements to risk equalization design may therefore be warranted. In this context, one way to better capture the variation in costs between consumers may be the introduction of a diagnosis-based risk-adjuster. Evidence from other countries suggests that the inclusion of a diagnosis-based risk-adjuster was able to eliminate the favorable risk profile of switchers [23, 24]. In addition, the substitution of the current utilization-based hospital night risk-adjuster could also potentially improve efficiency incentives as reimbursement would not be tied directly to length of hospital stay. However, research is needed into the feasibility of introducing diagnosis-based risk adjustment in the Irish PHI market before clear recommendations can be made.

Limitations

In the context of the above discussion, it is important to highlight some limitations of this analysis. Although VHI is by far the largest insurer in the market (both in terms of market share and claims payout), generalizing any results must be done with caution, as VHI has a worse risk profile than the overall market [37]. Secondly, whether a policy was flagged as switching to a competitor was based on voluntary information provided by the departing policyholder; consequently, there may be some under-representation of switchers in this analysis. Thirdly, the administrative nature of the data limited the number of potentially relevant variables at our disposal. Particularly, it was not possible to examine the effect of quality on switching behavior. In addition, we could not account for the effect of variables such as education, which raises potential concerns over omitted-variable bias [38]. Finally, this study focused exclusively on switchers out of VHI as there was relatively less information available on those joining. In addition to addressing the above limitations, future research should be cognizant of the need for longitudinal analysis to study the robustness of these effects over time.

Conclusions

Internationally, there is a lack of empirical research on consumer mobility in competitive PHI markets. Particularly, though a competitive health insurance market in Ireland has been in existence for close to two decades, this is the first detailed analysis of the determinants of consumer switching. A significant finding is that consumers are price sensitive, which is an important requirement of a well-functioning market. The young and the healthy are both more likely to switch insurers, while the young particularly are more price sensitive than the old. From a demand-side perspective, these associations may be related to low risks facing lower search and switching costs. However, while successive iterations of risk equalization have appeared to largely equalize costs between switchers and stayers, there may be some residual incentives for insurer risk selection still present in the market. In order to support community rating and deter risk selection, research is required into how risk equalization in Ireland can be improved.

Notes

This may not always be the case. For example, specific health insurance cover can be strongly linked to employment or certain eligibility criteria (e.g., Medicare or Medicaid in the United States).

Currently there are three other insurers competing in the market in conjunction with the incumbent VHI.

A contract is specified as providing for non-advanced cover if not more than 66 % of the full cost for hospital charges in a private hospital or prescribed minimum benefits, if lower, is always provided. Advanced contracts are contracts that are not non-advanced [39].

In 2013, VHI had 54 % share of the market and paid 67 % of total market claims [40].

HIA data suggest that roughly three in ten policyholders have access to work group schemes [28].

As this is a voluntary market, the other option faced by consumers is to drop coverage entirely. Those who did so were excluded from the analysis.

Average market premiums were calculated based on quarterly data provided by the HIA.

Pseudo R 2 statistics for all models are quite low, however this tends to be the norm in logistic regression analysis [41].

However, it is unclear whether the cost of investing in risk selection strategies for these individuals would outweigh the benefit.

As discussed, this rate relates to the policy level, not the individual level.

References

Thomson, S., Busse, R., Crivelli, L., van de Ven, W., Van de Voorde, C.: Statutory health insurance competition in Europe: a four-country comparison. Health Policy. (2013)

Laske-Aldershof, T., Schut, E., Beck, K., Gress, S., Shmueli, A., Van de Voorde, C.: Consumer mobility in social health insurance markets: a five-country comparison. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 3, 229–241 (2004)

Duijmelinck, D.M.I.D., Mosca, I., van de Ven, W.P.M.M.: Switching benefits and costs in competitive health insurance markets: a conceptual framework and empirical evidence from the Netherlands. Health Policy. (2014)

Lako, C.J., Rosenau, P., Daw, C.: Switching health insurance plans: results from a health survey. Health Care Anal. 19, 312–328 (2011)

Kiil, A.: What characterises the privately insured in universal health care systems? A review of the empirical evidence. Health Policy 106, 60–75 (2012)

DOH: the path to universal healthcare: white paper on universal health insurance, Dublin (2014)

Buchmueller, T.C., Feldstein, P.J.: The effect of price on switching among health plans. J. Health Econ. 16, 231–247 (1997)

Cutler, D.M., SJ, Reber: Paying for health insurance: the trade-off between competition and adverse selection. Q. J. Econ. 113, 433–466 (1998)

Royalty, A.B., Solomon, N.: Health plan choice: price elasticities in a managed competition setting. J. Hum. Resour. 34, 1–41 (1999)

Feldman, R., Finch, M., Dowd, B., Cassou, S.: The demand for employment-based health insurance plans. J. Hum. Resour. 24, 115 (1989)

Schut, F.T., Hassink, W.H.J.: Managed competition and consumer price sensitivity in social health insurance. J. Health Econ. 21, 1009–1029 (2002)

Schut, F.T., Gress, S., Wasem, J.: Consumer price sensitivity and social health insurer choice in Germany and The Netherlands. Int. J. Health Care Finance Econ. 3, 117–138 (2003)

Frank, R.G., Lamiraud, K.: Choice, price competition and complexity in markets for health insurance. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 71, 550–562 (2009)

Van den Berg, B., Van Dommelen, P., Stam, P., Laske-Aldershof, T., Buchmueller, T., Schut, F.T.: Preferences and choices for care and health insurance. Soc. Sci. Med. 66, 2448–2459 (2008)

Pendzialek, J.B., Danner, M., Simic, D., Stock, S.: Price elasticities in the German Statutory Health Insurance market before and after the health care reform of 2009. Health Policy. 119, 654–663 (2015)

Boonen, L.H.H.M., Laske-Aldershof, T., Schut, F.T.: Switching health insurers: the role of price, quality and consumer information search. Eur. J. Health Econ. (2015)

Gress, S., Groenewegen, P., Kerssens, J., Braun, B., Wasem, J.: Free choice of sickness funds in regulated competition: evidence from Germany and The Netherlands. Health Policy 60, 235–254 (2002)

Van Dijk, M., Pomp, M., Douven, R., Laske-Aldershof, T., Schut, E., de Boer, W., de Boo, A.: Consumer price sensitivity in Dutch health insurance. Int. J. Health Care Finance Econ. 8, 225–244 (2008)

Strombom, B.A., Buchmueller, T.C., Feldstein, P.J.: Switching costs, price sensitivity and health plan choice. J. Health Econ. 21, 89–116 (2002)

Kolstad, J.T., Chernew, M.E.: Quality and consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Med. Care Res. Rev. 66, 28S–52S (2009)

Reitsma-van Rooijen, M., de Jong, J.D., Rijken, M.: Regulated competition in health care: switching and barriers to switching in the Dutch health insurance system. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11, 95 (2011)

Hirschman, A.O.: Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations and States. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (1970)

Van Vliet, R.C.J.A.: Free choice of health plan combined with risk-adjusted capitation payments: are switchers and new enrolees good risks? Health Econ. 15, 763–774 (2006)

Behrend, C., Buchner, F., Happich, M., Holle, R., Reitmeir, P., Wasem, J.: Risk-adjusted capitation payments: how well do principal inpatient diagnosis-based models work in the German situation? Results from a large data set. Eur. J. Health Econ. 8, 31–39 (2007)

HIA: market figures. http://www.hia.ie/sites/default/files/HIA_Mar_Newsletter_2015.pdf (2015). Accessed 26 June 2015

Turner, B., Shinnick, E.: Community rating in the absence of risk equalisation: lessons from the Irish private health insurance market. Health Econ. Policy Law. 8, 209–224 (2013)

Armstrong, J.: Risk equalisation and voluntary health insurance markets: the case of Ireland. Health Policy 98, 15–26 (2010)

HIA: the private health insurance market in Ireland 2014., Dublin (2014)

Keegan, C., Thomas, S., Normand, C., Portela, C.: Measuring recession severity and its impact on healthcare expenditure. Int. J. Health Care Finance Econ. 13, 139–155 (2013)

HIA: Report on the Health Insurance Market: By Millward Brown Lansdowne to the Health Insurance Authority., Dublin (2012)

De Jong, J.D., van den Brink-Muinen, A., Groenewegen, P.P.: The Dutch health insurance reform: switching between insurers, a comparison between the general population and the chronically ill and disabled. BMC Health Serv. Res. 8, 58 (2008)

Dormont, B., Geoffard, P.-Y., Lamiraud, K.: The influence of supplementary health insurance on switching behaviour: evidence from Swiss data. Health Econ. 18, 1339–1356 (2009)

Shmueli, A., Bendelac, J., Achdut, L.: Who switches sickness funds in Israel? Health Econ. Policy Law 2, 251–265 (2007)

Breyer, F., Bundorf, M.K., Pauly, M.: Health care spending risk, health insurance, and payment to health plans. In: Handbook of Health Economics, pp. 691–762. Elsevier, Massachusetts (2012)

Turner, B.: Premium inflation in the Irish private health insurance market: drivers and consequences. Ir. J. Med. Sci. (2013)

The Competition Authority: Competition in the Private Health Insurance Market, Dublin (2007)

HIA: August 2014 Newsletter. http://www.hia.ie/assets/files/Newsletters/HIA_Aug_Newsletter_2014.pdf (2014). Accessed 20 June 2015

Greene, W.H.: Econometric Analysis. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River (2003)

HIA: Guide to 2013 Risk Equalisation Scheme., Dublin (2013)

VHI: VHI Healthcare Annual Report and Accounts 2012, Dublin (2012)

Hosmer, D.W., Lemeshow, S., Sturdivant, R.X.: Applied logistic regression. Wiley, Hoboken (2000)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank VHI Healthcare for access to their policyholder database. This research was funded by the Health Research Board PHD/2007/16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keegan, C., Teljeur, C., Turner, B. et al. Switching insurer in the Irish voluntary health insurance market: determinants, incentives, and risk equalization. Eur J Health Econ 17, 823–831 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-015-0724-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-015-0724-7