Abstract

The aim of the present study was to compare long-term adalimumab (ADA) and infliximab (IFX) retention rates in patients with intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis. Additional aims are as follows: (i) to identify any difference in the causes of treatment discontinuation between patients treated with ADA and IFX; (ii) to assess any impact of demographic features, concomitant treatments, and different lines of biologic therapy on ADA and IFX retention rates; and (iii) to identify any correlation between ADA and IFX treatment duration and the age at uveitis onset, the age at onset of the associated systemic diseases, and the age at the start of treatment. Clinical, therapeutic, and demographic data from patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis treated with ADA or IFX were retrospectively collected. Kaplan-Meier plot and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test were used to assess survival curves. One hundred eight patients (188 eyes) were enrolled; in 87 (80.6%) patients, uveitis was associated with a systemic disease. ADA and IFX were administered in 62 and 46 patients, respectively. No statistically significant differences were identified between ADA and IFX retention rates (p value = 0.22). Similarly, no differences were identified between ADA and IFX retention rates in relation to gender (p value = 0.61 for males, p value = 0.09 for females), monotherapy (p value = 0.08), combination therapy with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (log-rank p value = 0.63), and different lines of biologic therapy (p value = 0.79 for biologic-naïve patients; p value = 0.81 for subjects previously treated with other biologics). In conclusion, ADA and IFX have similar long-term retention rates in patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis. Demographic, clinical, and therapeutic features do not affect their long-term effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-infectious uveitis represents a protean group of inflammatory eye disorders affecting the uvea and the adjacent tissues. Uveitis may be idiopathic or related to systemic inflammatory disorders including Behçet’s disease (BD), Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, sarcoidosis and inflammatory bowel diseases [1].

Uveitis may be a challenging condition capable to severely affect patients’ quality of life by inducing visual loss up to complete blindness [2]. Indeed, uveitis accounts for 10–15% of all cases of total blindness in the developed world through sight-threatening complications including cystoid macular edema and choroidal neovascularization [3, 4]. For these reasons, the correct management of uveitis is essential for preventing ocular complications and preserving visual function. In this regard, topical and systemic corticosteroids represent the cornerstone of the therapy, while conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) are useful in resistant cases and/or as corticosteroid-sparing agents. More recently, monoclonal tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blockers such as infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA) have become a valuable addition to the therapeutic armamentarium for patients with refractory uveitis or patients that are intolerant to conventional treatments. Based on two recent prospective double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, ADA has been recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of non-infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis, especially when corticosteroids are inadequate and inappropriate or when corticosteroid-sparing is required [5,6,7]. However, current medical literature shows that also IFX is highly effective in the treatment of uveitis. In this context, the objective of our work was to compare the long-term effectiveness of ADA and IFX in patients with resistant uveitis by assessing any difference in their retention rates, the impact of demographic, clinical, and therapeutic factors on drug survival, and the role of specific causes of treatment discontinuation on ADA and IFX withdrawal.

Materials and methods

Patients treated with ADA or IFX because of non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis were retrospectively enrolled in the study. Uveitis had been classified according to the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group criteria [1]. Chest radiograph, Mantoux and/or QuantiFERON tests, and liver markers for HBV and HCV infections, HIV, syphilis, and toxoplasma had been performed before starting ADA or IFX to rule out any active or latent infection. Also, cardiac and malignant conditions had been ruled out. According to the best standard of care, patients were visited every 3 months or in case of ocular relapses or safety concerns by both a rheumatologist and an ophthalmologist. At each follow-up evaluation, BD current activity form (BDCAF) and ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS) were respectively employed as clinimetric tools in patients with BD and spondyloarthritis in order to assess the systemic disease activity. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was recorded at baseline and at each follow-up visit in all patients.

The following demographic, clinical, and therapeutic data were retrospectively collected: gender, age at uveitis onset, age at the start of biologic therapy, any systemic disease associated with uveitis, the age at the onset of the systemic diseases (when identified), previous and concomitant treatments, and the different lines of ADA and IFX therapy.

The primary aim of the study was to compare the long-term ADA and IFX retention rate. Secondary aims of the study were as follows: (i) to identify any difference in the specific causes leading to biologic treatment discontinuation between patients treated with ADA and those administered with IFX; (ii) to assess any impact of demographic features, concomitant treatments, and the different lines of biologic therapy on ADA and IFX retention rates; and (iii) to identify any correlation between the duration of treatment with ADA or IFX and the age at the start of therapy, the age at uveitis onset, and the age at the onset of any systemic diseases associated with uveitis (when identified).

The primary endpoint of the study was represented by the identification of a statistically significant difference between the Kaplan-Meier survival curves obtained from all patients treated with ADA or IFX. The secondary endpoints of the study were represented by (i) the observation of a statistically significant difference in the frequency analysis of specific causes leading to treatment withdrawal between patients undergoing ADA or IFX and (ii) the identification of a statistically significant difference in the Kaplan-Meier survival curves of ADA and IFX obtained in the following subgroups: male patients, female patients, patients treated with ADA or IFX as monotherapy, subjects undergoing combination therapy with cDMARDs, patients treated with ADA or IFX as their first biologic agent, subjects undergoing ADA of IFX as second line (or more) biologic agent, patients with posterior or panuveitis, and patients with concomitant retinal vasculitis. A further secondary endpoint of the study was represented by the identification of a statistically significant correlation between treatment duration and (i) the age at the onset of uveitis, (ii) the age at onset of any systemic disease associated with uveitis, and (iii) the age at the start of therapy.

The lack of efficacy was defined as a lack of disease control at the 3-month follow-up evaluation; loss of efficacy was defined as a disease relapse unresponsive to treatment adjustments after a previous disease control of at least 3 months. The loss of compliance was the failure to adhere to the treatment strategy after having started therapy.

Adverse events were defined according to the directions of the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/patientsafety/taxonomy/icps_full_report.pdf). The study protocol was conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Committee of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese, Siena, Italy, approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled.

Descriptive statistics included sample size, percentages, mean, and standard deviation. Drug survival rates were analyzed by using the Kaplan-Meier plot with “time 0” corresponding to the start of treatments and the event being the discontinuation of therapy. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to compare survival curves. After having assessed normality distribution with the Anderson-Darling test, Pearson or Spearman tests (as appropriate) were used to evaluate correlations; pairwise comparisons were performed by using unpaired two-tailed t test or Mann-Whitney two-tailed U test (as appropriate) for quantitative variables and Fisher exact test for qualitative variables. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) 24.0 package was used for statistical analysis. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

In total, 108 patients with uveitis treated with ADA or IFX were enrolled. Unilateral uveitis was observed in 28 (25.9%) patients; bilateral uveitis was described in 80 (74.1%) patients. The total number of eyes with uveitis was 188. In detail, 46 (42.6%) patients had posterior uveitis, 59 (54.6%) panuveitis, and 3 (2.8%) had intermediate uveitis.

The mean age at uveitis onset was 30.94 ± 14.57 years; the mean uveitis disease duration was 10.58 ± 8.51 years; the mean age at the start of treatment was 41.72 ± 13.51 years. In 87 (80.6%) patients, uveitis was associated with a specific systemic disease, while diagnosis of idiopathic uveitis was recorded in 21 (19.4%) cases. Among systemic diseases, BD was identified in 80 patients, inflammatory bowel diseases in 3 cases, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in 2 subjects, sarcoidosis in 1 case, and spondyloarthritis in 1 patient. The mean time at the onset of the associated systemic diseases was 24.16 ± 15.49 years; at the start of treatment, the mean duration of systemic diseases was 10.36 ± 10.5 years.

IFX was used in 46 patients and ADA in 62 patients. The mean treatment duration was 25.85 ± 21.42 months for patients treated with ADA and 61.45 ± 53.75 months for subjects administered with IFX. Among subjects treated with IFX, the most employed dosages were 5 mg/Kg every 6 weeks (29 patients) and 5 mg/Kg every 8 weeks (17 patients); all patients treated with ADA were administered with 40 mg every other week. Table 1 describes demographic features of the patients enrolled, the type of inflammatory ocular involvement, and previous and concomitant treatments.

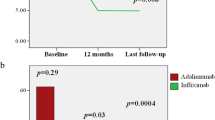

When comparing ADA and IFX drug retention rates, no statistically significant differences were identified (log-rank p value = 0.22). The corresponding Kaplan-Meyer survival curves are illustrated in Fig. 1a, while specific causes of ADA and IFX discontinuation over time are shown in Table 2. The lack of significant difference between ADA and IFX retention rates was maintained when statistical analysis was performed among patients with posterior uveitis (log-rank p value = 0.42), panuveitis (log-rank p value = 0.92), and retinal vasculitis (log-rank p value = 0.53). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 1b, no statistically significant difference was found in the subgroup of patients diagnosed with BD (log-rank p value = 0.07).

When evaluating gender, the retention rate of ADA and IFX did not change in a significant manner neither in male nor in female subjects (log-rank p value = 0.61 and log-rank p value = 0.09, respectively). Similarly, no statistically significant differences were identified in the drug retention rate of ADA and IFX among patients co-administered with cDMARDs (log-rank p value = 0.63, Fig. 2a) as well as among those treated with TNF-α inhibitors as monotherapy (log-rank p value = 0.08, Fig. 2b). In addition, no differences were highlighted in the subgroups of biologic-naïve patients (log-rank p value = 0.79, Fig. 2c) and among subjects treated with at least one previous biologic agent (second-line or more biologic therapy) (log-rank p value = 0.81, Fig. 2d).

Adalimumab (ADA) and infliximab (IFX) Kaplan-Meier survival curves among patients concomitantly treated with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (a), patients undergoing TNF-α inhibition as monotherapy (b), biologic-naïve subjects (c), and patients already treated with other biologic agents before starting ADA or IFX (d)

Among patients treated with ADA and IFX, no significant correlations were disclosed between treatment duration and the age at uveitis onset (rho = 0.10, p = 0.67 for ADA; rho = − 0.17, p = 0.53 for IFX), uveitis duration (rho = 0.14, p = 0.56 for ADA; rho = 0.16, p = 0.56 for IFX), age at onset of the systemic disease associated with uveitis (rho = 0.08, p = 0.73 for ADA; rho = 0.05, p = 0.89 for IFX), and the duration of the systemic disease (rho = 0.37, p = 0.1 for ADA; rho = 0.25, p = 0.46 for IFX).

Regarding the safety profile, two cases of urticarial skin rash occurred soon after ADA injection. Among patients treated with IFX, four adverse events were reported: dyspnea after treatment infusion in one patient, one case of not otherwise explainable dizziness, recurrent severe asthenia starting soon after IFX administrations in one patient, and leukocytosis in a last case.

Discussion

During the last decade TNF-α antagonists have revolutionized the therapy for patients with non-infectious uveitis. In this regard, the FDA has recently approved ADA for the treatment of non-infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis, especially in patients with inadequate response to corticosteroids, when corticosteroid treatment is inappropriate or when corticosteroid-sparing is needed. Actually, ADA has proved to be a successful treatment option in almost all clinical contexts related to non-infectious uveitis [8,9,10,11,12,13]. In detail, the efficacy of ADA has been reported in two double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies on patients with active and inactive non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis [5, 6]. In both clinical trials, ADA brought about a significant improvement of the median time to treatment failure when compared to placebo and a decrease by 50% of the risk of treatment failure in patients with active uveitis. Moreover, better results were obtained with ADA over placebo in terms of vitreous haze, anterior chamber cell grade, changes in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and identification of new active inflammatory lesions [5]. Similar results were obtained in terms of median time to treatment failure and BCVA among patients undergoing ADA during an inactive phase [6]. More recently, the long-term efficacy of ADA has also been ascertained [7].

IFX is the other TNF-α inhibitor more frequently employed in patients with uveitis [14]. Although no prospective clinical trials are currently available, an increasing number of studies have been reported during the last decade on the effectiveness of IFX in patients with non-infectious uveitis, also determining a steroid-sparing effect and improvement of visual outcome, especially when used at an early stage [14,15,16,17,18].

Both ADA and IFX long-term retention rates have been separately assessed in patients with BD-related uveitis, in order to evaluate the efficacy of TNF-α inhibition with monoclonal antibodies over time [18, 19]. In detail, ADA retention rate was 63.5% at 48-month follow-up with no statistically significant differences according to the concomitant use of cDMARDs or the different lines of biologic therapy [19]. On the other hand, IFX retention rate was 75.55% at 60-month follow-up and 47.11% at 120-month follow-up with no statistically significant differences according to the concomitant use of cDMARDs. Conversely, IFX drug retention rate has shown to be significantly higher among biologic-naïve patients than that among subjects previously treated with other biologics [18]. Both ADA and IFX rates of discontinuation in BD were not affected by demographic or clinical variables known to be associated with a higher disease severity including age, gender, age at BD onset, overall BD duration, age at uveitis onset, uveitis duration, and HLA-B51 positivity [18, 19]. Accordingly, a further study on 64 BD patients treated with 85 different biologic regimens (57% of which owing to active ocular involvement) showed ADA and IFX retention rates of about 65% and 75% respectively at 5-year follow-up assessment [20].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare ADA and IFX long-term retention rates in patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis. In this regard, no statistically significant differences were identified between the two biologic agents. In addition, no statistically significant differences were found between ADA and IFX in the frequency of specific causes of treatment discontinuation including lack and loss of efficacy, safety concerns, and patients’ compliance. Overall, these findings suggest a comparable role of the two monoclonal TNF-α inhibitors with a similar efficacy and safety profile during the long-term treatment of patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis.

In contrast to our results, Abásolo et al. found that a sustained clinical efficacy represented the major cause of treatment withdrawal in patients with uveitis treated with immunosuppressants including TNF-α inhibitors [21]. This divergence could be due to the different cohorts of patients enrolled. Indeed, most of treatment courses analyzed by Abásolo et al. were represented by cDMARDs, while all patients enrolled in the present study have undergone anti-TNF-α treatment. As patients selected for TNF-α inhibition are generally more severely affected, a more aggressive or resistant ocular inflammation might be supposed in our patients. In addition, in our study, the shorter follow-up may have also played a role in determining a different weight for the specific causes of treatment discontinuation.

The lack of significant differences between ADA and IFX survival rates was maintained when subgroup analysis was performed. Specifically, no statistically significant differences were found between ADA and IFX survival rates in the subgroup of patients with BD, which was the most frequent systemic disease in our cohort of patients. Similarly, no statistically significant differences were found in relation to the concomitant use of cDMARDs, or according to the different lines of biologic treatment. Similarly, no differences were identified in the subgroup of patients with panuveitis or posterior uveitis or among patients with concomitant retinal vasculitis. Therefore, the comparable long-term effectiveness of ADA and IFX was not affected by concomitant demographic, clinical, or therapeutic factors including the different types of uveitis, the concomitant use of cDMARDs, and the different lines of biologic therapy. Nevertheless, although statistically significant differences were not identified, a trend towards significance was observed in favor of IFX when survival analysis was performed in the subgroup of patients with BD. However, studies on a higher number of patients are warranted in order to disclose whether this is a by-chance finding or may have a real clinical meaning.

As for previous reports, no correlations were identified between treatment duration and clinical variables known to be negative prognostic factors for uveitis, including age of patients at the start of treatments, age at systemic disease onset, age at uveitis onset, systemic disease duration, and uveitis duration [18,19,20, 22, 23]. Similarly, no statistically significant differences were found in the retention rates of ADA and IFX based on gender distinctions.

Of note, none of the patients treated with IFX and only one patient administered with ADA discontinued their treatment because of a loss of compliance. This result seems to suggest that the different route of administration does not affect the long-term retention rate and the need for the in-hospital administration of IFX not necessarily implies less acceptance by patients.

The main limitation of our study is represented by its retrospective design. However, this is the first study comparing the long-term survival of the two monoclonal TNF-α inhibitors that are most frequently used in the treatment of intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, ADA and IFX have shown similar long-term drug retention rates with comparable overall efficacy and safety profile in patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis. The concomitant use of cDMARDs, the different lines of biologic administration, the specific type of ocular involvement, and the concomitant occurrence of retinal vasculitis do not affect the similar long-term effectiveness of ADA and IFX. The in-hospital administration required by IFX has not induced any loss of compliance over time with no impact on the long-term retention rate.

References

Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group (2005) Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 140:509–516

Fabiani C, Vitale A, Orlando I, Capozzoli M, Fusco F, Rana F, Franceschini R, Sota J, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Marco Tosi G, Cantarini L (2017) Impact of uveitis on quality of life: a prospective study from a tertiary referral rheumatology-ophthalmology collaborative uveitis center in Italy. Isr Med Assoc J 19:478–483

Rothova A, Suttorp-van Schulten MS, Frits Treffers W, Kijlstra A (1996) Causes and frequency of blindness in patients with intraocular inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol 80:332–336

Gritz DC, Wong IG (2004) Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology 111:491–500

Jaffe GJ, Dick AD, Brézin AP, Nguyen QD, Thorne JE, Kestelyn P, Barisani-Asenbauer T, Franco P, Heiligenhaus A, Scales D, Chu DS, Camez A, Kwatra NV, Song AP, Kron M, Tari S, Suhler EB (2016) Adalimumab in patients with active noninfectious uveitis. N Engl J Med 375:932–943

Nguyen QD, Merrill PT, Jaffe GJ, Dick AD, Kurup SK, Sheppard J, Schlaen A, Pavesio C, Cimino L, Van Calster J, Camez AA, Kwatra NV, Song AP, Kron M, Tari S, Brézin AP (2016) Adalimumab for prevention of uveitic flare in patients with inactive non-infectious uveitis controlled by corticosteroids (VISUAL II): a multicentre, double-masked, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 388:1183–1192

Suhler EB, Jaffe GJ, Nguyen QD, Antoine P. Brezin, Manfred Zierhut, Albert Vitale, van Velthoven M, Adan A, Lim L, Kramer M, Schlaen A, Fortin E, Muccioli C, Goto H, Kaburaki T, Camez A, Song AP, Kron M, Tari S, Dick AD (2016) Long-term safety and efficacy of adalimumab in patients with non-infectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis in an ongoing open-label study [abstract 1335]. Arthritis Rheumatol 68(Suppl 10)

Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Benton D, Compeyrot-Lacassagne S, Dawoud D, Hardwick B, Hickey H, Hughes D, Jones A, Woo P, Edelsten C, Beresford MW (2014) A randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of adalimumab in combination with methotrexate for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated uveitis (SYCAMORE Trial). Trials 15:14

Fabiani C, Vitale A, Emmi G, Vannozzi L, Lopalco G, Guerriero S, Orlando I, Franceschini R, Bacherini D, Cimino L, Soriano A, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Iannone F, Tosi GM, Salvarani C, Cantarini L (2017) Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Behçet’s disease-related uveitis: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Clin Rheumatol 36:183–189

Rudwaleit M, Rødevand E, Holck P, Vanhoof J, Kron M, Kary S, Kupper H (2009) Adalimumab effectively reduces the rate of anterior uveitis flares in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a prospective open-label study. Ann Rheum Dis 68:696–701

Erckens RJ, Mostard RL, Wijnen PA, Schouten JS, Drent M (2012) Adalimumab successful in sarcoidosis patients with refractory chronic non-infectious uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 250:713–720

Fabiani C, Vitale A, Lopalco G, Iannone F, Frediani B, Cantarini L (2016) Different roles of TNF inhibitors in acute anterior uveitis associated with ankylosing spondylitis: state of the art. Clin Rheumatol 35:2631–2638

Quartier P, Baptiste A, Despert V, Allain-Launay E, Koné-Paut I, Belot A, Kodjikian L, Monnet D, Weber M, Elie C, Bodaghi B, ADJUVITE Study Group (2017) ADJUVITE: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of adalimumab in early onset, chronic, juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated anterior uveitis. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212089

Cordero-Coma M, Sobrin L (2015) Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol 60:575–589

Markomichelakis N, Delicha E, Masselos S, Fragiadaki K, Kaklamanis P, Sfikakis PP (2011) A single infliximab infusion vs corticosteroids for acute panuveitis attacks in Behçet’s disease: a comparative 4-week study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 50:593–597

Guzelant G, Ucar D, Esatoglu SN, Hatemi G, Ozyazgan Y, Yurdakul S, Seyahi E, Yazici H, Hamuryudan V (2017) Infliximab for uveitis of Behçet’s syndrome: a trend for earlier initiation. Clin Exp Rheumatol 35(Suppl 108):86–89

Keino H, Okada AA, Watanabe T, Nakayama M, Nakamura T (2017) Efficacy of infliximab for early remission induction in refractory uveoretinitis associated with Behçet disease: a 2-year follow-up study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 25:46–51

Fabiani C, Sota J, Vitale A, Emmi G, Vannozzi L, Bacherini D, Lopalco G, Guerriero S, Venerito V, Orlando I, Franceschini R, Fusco F, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Iannone F, Tosi GM, Cantarini L (2017) Ten-year retention rate of infliximab in patients with Behçet’s disease-related uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2017.1391297

Fabiani C, Sota J, Vitale A, Rigante D, Emmi G, Vannozzi L, Bacherini D, Lopalco G, Guerriero S, Gentileschi S, Capozzoli M, Franceschini R, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Iannone F, Tosi GM, Cantarini L (2017) Cumulative retention rate of adalimumab in patients with Behçet’s disease-related uveitis: a four-year follow-up study. Br J Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310733

Cantarini L, Talarico R, Generali E, Emmi G, Lopalco G, Costa L, Silvestri E, Caso F, Franceschini R, Cimaz R, Iannone F, Galeazzi M, Selmi C (2017) Safety profile of biologic agents for Behçet’s disease in a multicenter observational cohort study. Int J Rheum Dis 20:103–108

Abásolo L, Rosales Z, Díaz-Valle D, Gómez-Gómez A, Peña-Blanco RC, Prieto-García Á, Benítez-Del-Castillo JM, Pato E, García-Feijoo J, Fernández-Gutiérrez B, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L (2016) Immunosuppressive drug discontinuation in noninfectious uveitis from real-life clinical practice: a survival analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 169:1–8

Sakamoto M, Akazawa K, Nishioka Y, Sanui H, Inomata H, Nose Y (1995) Prognostic factors of vision in patients with Behçet disease. Ophthalmology 102:317–321

Kang EH, Park JW, Park C, Yu HG, Lee EB, Park MH, Song YW, Song YW (2013) Genetic and non-genetic factors affecting the visual outcome of ocular Behcet’s disease. Hum Immunol 74:1363–1367

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

The study protocol was conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Committee of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese, Siena, Italy, approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled.

Disclosures

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fabiani, C., Vitale, A., Emmi, G. et al. Long-term retention rates of adalimumab and infliximab in non-infectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis. Clin Rheumatol 38, 63–70 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4069-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4069-3