Abstract

Glucose tolerant subjects with 1-h post-load glucose ≥155 mg/dl (NGT-1 h-high) are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Prospective studies showed that chronic subclinical inflammation is a predictor of T2DM. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the inflammatory profile in NGT-1 h-high subjects as compared with individuals with 1-h post-load glucose <155 mg/dl (NGT-1 h-low). To this end, an oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) were performed in 1,099 nondiabetic whites. Cardio-metabolic risk factors including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), fibrinogen, and complement C3 (C3) were determined. Of the 1,099 subjects examined, 497 had NGT-1 h-low, 154 had NGT-1 h-high, 158 had isolated impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and 290 had impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). As compared with NGT-1 h-low, NGT-1 h-high and IGT subjects exhibited significantly higher hsCRP, ESR, fibrinogen, and C3 levels. Notably, hsCRP, ESR, and C3 were also significantly higher as compared with IFG individuals. In a logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and gender, NGT-1 h-high and IGT subjects had a 1.8-fold increased risk of having the highest value of the Inflammatory Score. These data suggest that a value of a 1-h OGTT glucose ≥155 mg/dl may be helpful to identify a subset of normal glucose tolerance individuals at risk for chronic subclinical inflammation, a predictor of T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) has increased to epidemic proportions, and reliable screening tools aimed at identifying high risk individuals who may benefit from lifestyle modification or pharmacological intervention [1–4] are essential to prevent T2DM. Early detection of subjects at risk for T2DM is crucial not only for prevention of T2DM but also of the associated cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [5, 6]. Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) are conditions of impaired glucose metabolism [7–9], which represent intermediate stages in the transition from normal glucose tolerance (NGT) to overt T2DM. However, longitudinal studies have demonstrated the limitation of IFG and IGT in predicting diabetes risk, as ~40 % of individuals who develop T2DM have NGT at baseline [10]. It has been shown that plasma glucose concentration ≥155 mg/dl at 1 h during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) can identify NGT individuals at increased risk for T2DM (NGT-1 h-high) [11, 12]. NGT-1 h-high individuals exhibit a worse cardio-metabolic risk profile having cardio-metabolic abnormalities and signs of subclinical organ damage similar to those of IGT individuals [13–22]. Notably, 1-h post-load glucose levels have been reported to predict cardiovascular mortality in longitudinal studies [23, 24] suggesting that additional information about the risk for T2DM and CVD is embedded in 1-h post-load glucose levels.

Chronic subclinical inflammation has been associated with T2DM and CVD [25–27]. Among markers of subclinical inflammation, the most reliable for clinical use is high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), but other markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), fibrinogen, and complement C3 (C3) have been associated with T2DM [25–31]. In addition, there is evidence that fibrinogen and C3 interact producing clots more resistant to lysis [32] thus providing a link between inflammation and prothrombotic state. Because several markers of inflammation have been associated with T2DM, it is conceivable that a cluster of inflammatory markers occurs in individuals with NGT-1 h-high. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the inflammatory profile of NGT-1 h-high subjects as compared with individuals with 1-h post-load plasma glucose <155 mg/dl (NGT-1 h-low).

Materials and methods

The study group consisted of 1,099 White subjects participating to the CATAnzaro MEtabolic RIsk factors (CATAMERI) Study, a cross-sectional study evaluating cardio-metabolic risk factors in carriers at least one risk factor including dysglycemia, overweight/obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and family history of T2DM [14]. Exclusion criteria included the following: known diabetes, history of malignant disease, end-stage renal disease, chronic gastrointestinal diseases, positivity for antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), history of alcohol abuse, immunological diseases, and acute infections.

After a 12-h fasting, all individuals underwent anthropometrical evaluation, and a venous blood sample was drawn for laboratory determinations. A 75 g OGTT was performed with 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min sampling for plasma glucose and insulin measurements. Three consecutive measurements of blood pressure were obtained in the left arm of supine patients.

Subjects were classified according to glucose tolerance status as having normal glucose tolerance (NGT) when fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was <100 mg/dl and 2-h post-load <140 mg/dl, isolated impaired fasting glucose (IFG) when FPG was 100–125 mg/dl and 2-h post-load <140 mg/dl, and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) when FPG was <126 mg/dl and 2-h post-load was 140–199 mg/dl.

The protocol was approved by the Hospital ethical committee (Comitato Etico Azienda Ospedaliera “Mater Domini”) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Analytical determinations

Glucose, triglycerides, total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentrations were determined by enzymatic methods (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). ESR was measured automatically by the stopped-flow technique in a capillary microphotometer (Alifax Test 1 System Polverara, Italy). Fibrinogen and C3 were measured by an automated nephelometric technology using the BN™II System analyzer (Siemens Healthcare, Italy). Levels of hsCRP were measured by an automated analyzer (CardioPhase® hsCRP, Siemens Healthcare, Italy) and insulin by a chemiluminescence-based assay (Immulite®, Siemens Healthcare, Italy).

Calculations

The Matsuda index of insulin sensitivity (ISI) was calculated as follows: 10.000/square root of [FPG x fasting insulin] × [mean glucose x mean insulin during OGTT] [33].

We aimed to quantify the inflammatory state using an Inflammatory Score [25]. This score was generated by attributing one point for a value greater than the median of the study sample for each of the four measured inflammation markers (hsCRP, ESR, fibrinogen, and C3) and ranged from 1 (lowest median value for each of the four inflammatory markers) to 5 (highest median value for each of the four inflammatory markers).

Statistical analysis

Variables with skewed distribution including triglycerides, hsCRP, ESR, fasting, 1-, and 2-h insulin were natural log transformed for statistical analyses. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were compared by χ 2 test. Anthropometric and metabolic differences between groups were tested after adjusting for age and gender using a general linear model with post hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association between the study groups and the highest value of the Inflammatory Score. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software program version 16.0 for Windows.

Results

Of the 1,099 subjects examined, 651 (59.2 %) had NGT, 158 (14.4 %) had isolated IFG, and 290 (26.4 %) had IGT. NGT subjects were divided into two groups: 497 subjects with NGT-1 h-low and 154 individuals with NGT-1 h-high. Table 1 shows the clinical data of the four study groups. Significant differences between the four groups were observed with respect to gender (higher prevalence of men among NGT-1 h-high, isolated IFG, and IGT as compared with NGT-1 h-low) and age (NGT-1 h-high, isolated IFG, and IGT, were older than NGT-1 h-low), and, therefore, all analyses were adjusted for age and gender.

NGT-1 h-high individuals had a metabolic risk profile which was intermediate between the one observed in NGT-1 h-low and the one of IGT individuals. NGT-1 h-high subjects exhibited significantly higher BMI, triglycerides, 2-h post-load glucose, 1- and 2-h post-challenge insulin and lower HDL levels and insulin sensitivity, assessed by the ISI index, as compared with NGT-1 h-low subjects. NGT-1 h-high individuals exhibited significantly higher values of all the four inflammatory markers measured, i.e., hsCRP, ESR, fibrinogen, and C3 as compared with NGT-1 h-low subjects. Notably, values of hsCRP, ESR, and C3 were also significantly higher as compared with IFG individuals.

As compared with NGT-1 h-low, IGT subjects exhibited the worse metabolic risk profile having significantly higher BMI, waist circumference, fasting and 1-h post-challenge glucose, fasting, 1- and 2-h post-challenge insulin levels, triglycerides, lower HDL and insulin sensitivity. By definition, IGT subjects exhibited higher 2-h post-challenge glucose levels. Values of hsCRP, ESR, fibrinogen, and C3 were significantly higher as compared with NGT-1 h-low individuals.

As compared with NGT-1 h-low, IFG subjects exhibited higher 1- and 2-h post-load glucose, fasting, 1- and 2-h post-challenge insulin levels, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and lower insulin sensitivity. By definition, IFG subjects exhibited higher FPG as compared with the other groups. Notably, hsCRP, ESR, and C3 were not significantly different from NGT-1 h-low individuals.

Subjects were classified in five categories according to their Inflammation Score ranging from 1 (lowest median value for each of the four inflammatory markers) to 5 (highest median value for each of the four inflammatory markers) (Table 2). Each one point increase of the Inflammation Score was associated with a progressive increase in hsCRP, ESR, fibrinogen, and C3 (Table 2). As compared with NGT-1 h-low individuals, a greater proportion of individuals with NGT-1 h-high or IGT had the highest value of the Inflammatory Score, i.e., highest median value for each of the four inflammatory markers (Table 1). By contrast, no association with the highest value of the Inflammatory Score was observed in IFG as compared with NGT-1 h-low individuals.

A logistic regression model adjusted for age and gender was used to compare the risk of NGT-1 h-high, IFG, and IGT to have the highest value of the Inflammatory Score as compared with the NGT-1 h-low group (the reference category) (Table 3). NGT-1 h-high and IGT subjects had a 1.8-fold increased risk of having the highest value of the Inflammatory Score, but no association with the Inflammatory Score was observed in the IFG group.

Discussion

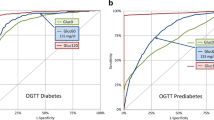

There is evidence that a significant proportion of NGT individuals are at risk for T2DM and CVD [10, 34]. Recently, longitudinal studies have shown that a cutoff point of 155 mg/dl for the 1-h post-load plasma glucose during the OGTT is able to identify a subgroup of NGT individuals (NGT-1 h-high) at risk of developing T2DM [11, 12]. The predictive power of 1-h post-load plasma glucose during the OGTT for future development of type 2 diabetes was measured using the area under the receiver-operating curve (ROC) and compared to the area under the ROC of fasting or 2-h post-load plasma glucose concentrations [35]. The area under ROC for 1-h post-load plasma glucose concentration was significantly greater (0.84) as compared with both fasting (0.75) and 2-h post-load plasma glucose concentrations (0.79) ROCs (both P = 0.01) [35].

It is increasingly recognized that chronic subclinical inflammation precedes and predicts the development of T2DM and CVD [25–31]. In this study, we provide evidence that NGT-1 h-high subjects have an unfavorable inflammatory profile as compared with NGT-1 h-low individuals. NGT-1 h-high subjects exhibit a clustering of inflammatory markers, as measured by the Inflammatory Score, similar to that observed in IGT subjects. By contrast, as compared with NGT-1 h-low, IFG subjects do not exhibit an unfavorable inflammatory profile. These data are consistent with those showing that levels of plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6), a major pro-inflammatory molecule acting on the liver to stimulate the production of acute-phase proteins such as CRP and fibrinogen, are increased in IGT but not in IFG subjects [9]. The pathophysiological mechanisms explaining the associations between subclinical inflammation and 1-h post-load hyperglycemia are unsettled. It is conceivable that post-load hyperglycemia acutely increases circulating cytokine concentrations by oxidative mechanisms [36]. An amplified acute-phase response to post-meal hyperglycemia may be a unifying mechanism explaining the increased risk for T2DM and CVD [11, 12, 23, 24, 37, 38] observed in individuals with elevated 1-h post-load glucose.

The present findings may have clinical implications suggesting that a value of 1-h OGTT glucose ≥155 mg/dl may be helpful to capture a subgroup of NGT individuals who may benefit from lifestyle modification and, possibly, pharmacotherapy to prevent or delay adverse clinical outcomes.

The cross-sectional design of the present study precludes us to draw any conclusion on the role of 1-h post-load plasma glucose values and related inflammatory state in occurrence of overt T2DM and cardiovascular events and, therefore, a cause–effect relationship cannot be firmly established. Importantly, a 5-year follow-up examination of the population described in the present study is ongoing to assess the role of 1-h OGTT glucose ≥155 mg/dl in glucose homeostasis deterioration and incident cardiovascular disease.

The present study has several strengths including the large sample size comprising both sexes, the detailed anthropometric and biochemical data collected by trained staff, the assay of biochemical variables in fresh blood samples rather than in stored samples, and the exclusion of confounding conditions characterized by elevation in inflammatory molecules.

However, our study has potential limitations that merit comment. First, all participants underwent a single OGTT. Although such an approach is common in clinical practice and in large epidemiological studies, these determinations are subject to intra-individual variability, and this may have introduced some imprecision in the classification of participants into the glucose tolerance categories. Measurements of inflammatory markers were made on fasting samples; therefore, we may not have fully captured the effects of post-load hyperglycemia on inflammation. Additionally, higher prevalence of men among NGT-1 h-high, isolated IFG, and IGT was observed as compared with NGT-1 h-low. However, all comparisons were corrected for gender thus taking into account this potential confounder. Next, our study is based on outpatients recruited at a referral university hospital, representing individuals at risk for cardio-metabolic diseases, and, therefore, may not be extendible to the general population. Finally, our findings may apply only to White Europeans and should not be extended to other ethnic groups.

References

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG et al (2001) Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 344:1343–1350

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE et al (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R et al (2002) Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the STOP-NIDDM randomised trial. Lancet 359:2072–2077

DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D, Schwenke DC et al (2011) Pioglitazone for diabetes prevention in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 364:1104–1115

Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R et al (2003) Acarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: the STOP-NIDDM trial. JAMA 290:486–494

Ratner R, Goldberg R, Haffner S et al (2005) Impact of intensive lifestyle and metformin therapy on cardiovascular disease risk factors in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care 28:888–894

Nathan DM, Davidson MB, DeFronzo RA et al (2007) Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: implications for care. Diabetes Care 30:753–759

Laakso M, Zilinskaite J, Hansen T et al (2008) Insulin sensitivity, insulin release and GLP-1 levels in subjects with IFG and/or IGT in the EUGENE2 study. Diabetologia 51:502–511

Cardellini M, Andreozzi F, Laratta E et al (2007) Plasma interleukin-6 levels are increased in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance but not in those with impaired fasting glucose in a cohort of Italian Caucasians. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 23:141–145

Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KG (2002) Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycemia: the current status on definition and intervention. Diabet Med 19:708–723

Abdul-Ghani MA, Abdul-Ghani T, Ali N, Defronzo RA (2008) One-hour plasma glucose concentration and the metabolic syndrome identify subjects at high risk for future type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 31:1650–1655

Abdul-Ghani MA, Lyssenko V, Tuomi T et al (2009) Fasting versus post-load plasma glucose concentration and the risk for future type 2 diabetes: results from the Botnia study. Diabetes Care 32:281–286

Succurro E, Marini MA, Arturi F et al (2009) Elevated one-hour post-load plasma glucose levels identifies subjects with normal glucose tolerance but early carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 207:245–249

Succurro E, Arturi F, Lugarà M et al (2010) One-hour post-load plasma glucose levels are associated with kidney dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:1922–1927

Bardini G, Dicembrini I, Cresci B, Rotella CM (2010) Inflammation markers and metabolic characteristics of subjects with 1-h plasma glucose levels. Diabetes Care 33:411–413

Sciacqua A, Miceli S, Carullo G et al (2011) One-hour post-load plasma glucose levels and left ventricular mass in hypertensive patients. Diabetes Care 34:1406–1411

Sciacqua A, Miceli S, Greco L et al (2011) One-hour post-load plasma glucose levels and diastolic function in hypertensive patients. Diabetes Care 34:2291–2296

Succurro E, Arturi F, Grembiale A et al (2011) One-hour post-load plasma glucose levels are associated with elevated liver enzymes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 21:713–718

Marini MA, Succurro E, Frontoni S et al (2012) Insulin sensitivity, β-cell function, and incretin effect in individuals with elevated 1-h postload plasma glucose levels. Diabetes Care 35:868–872

Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Tassone EJ et al (2012) One-hour post-load plasma glucose and IGF-1 in hypertensive patients. Eur J Clin Invest 42:1325–1331

Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Perticone M et al (2012) Serum uric acid and 1-h postload glucose in essential hypertension. Diabetes Care 35:153–157

Sciacqua A, Maio R, Miceli S et al (2012) Association between one-hour post-load plasma glucose levels and vascular stiffness in essential hypertension. PLoS ONE 7:e44470

Orencia AJ, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR et al (1997) One hour postload plasma glucose and risks of fatal coronary heart disease and stroke among nondiabetic men and women: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry (CHA) Study. J Clin Epidemiol 50:1369–1376

Strandberg TE, Pienimäki T, Strandberg AY et al (2011) One-hour glucose, mortality, and risk of diabetes: a 44-year prospective study in men. Arch Intern Med 171:941–943

Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Pinked JS et al (2003) Low-grade systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes. The arteriosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes 52:1799–1805

Perticone F, Maio R, Sciacqua A et al (2008) Endothelial dysfunction and CRP are risk factors for diabetes in essential hypertension. Diabetes 57:167–171

Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E et al (2012) C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and cardiovascular disease prediction. N Engl J Med 367:1310–1320

Ridker PM, Wilson PW, Grundy SM (2004) Should C-reactive protein be added to metabolic syndrome and to assessment of global cardiovascular risk? Circulation 109:2818–2825

Ford ES (2002) Leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and diabetes incidence in a national sample of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 155:57–64

Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Sharett AR et al (1999) Markers of inflammation and prediction of diabetes mellitus in adults (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study): a cohort study. Lancet 353:1649–1652

Engstrom G, Hedblad B, Eriksson KF et al (2005) Complement C3 is a risk factor for the development of diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes 54:570–575

Hess K, Alzahrani SH, Mathai M et al (2013) A novel mechanism for hypofibrinolysis in diabetes: the role of complement C3. Diabetologia 55:1103–1113

Matsuda M, De Fronzo RA (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470

Levitan EB, Song Y, Ford ES, Liu S (2004) Is nondiabetic hyperglycemia a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Arch Intern Med 164:2147–2155

Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo RA, Stern M (2007) What is the best predictor of future type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care 30:1544–1548

Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R et al (2002) Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation 106:2067–2072

Verma S, Wang CH, Li SH et al (2002) A self-fulfilling prophecy: C-reactive protein attenuates nitric oxide production and inhibits angiogenesis. Circulation 106:913–919

D’Alessandris C, Lauro R, Presta I, Sesti G (2007) C-Reactive protein induces phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on Ser307 and Ser612 in L6 myocytes, thereby impairing the insulin signalling pathway that promotes glucose transport. Diabetologia 50:840–849

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by Italian Ministry of University Grant FIRB/MERIT RBNE08NKH7_002 to G.S.

Conflict of interest

None.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were approved by approved Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Rome Tor Vergata and Catanzaro and in accordance with the ethical of the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Managed by Massimo Federici.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sesti, G., Fiorentino, T.V., Succurro, E. et al. Elevated 1-h post-load plasma glucose levels in subjects with normal glucose tolerance are associated with unfavorable inflammatory profile. Acta Diabetol 51, 927–932 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-013-0539-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-013-0539-x