Abstract

The aim of this paper was to perform a systematic overview of secondary literature studies on care pathways (CPs) for hip fracture (HF). The online databases MEDLINE–PubMed, Ovid–EMBASE, CINAHL–EBSCO–host, and The Cochrane Library were searched. A total of six papers, corresponding to six secondary studies, were included but only four secondary studies were HF-specific and thus assessed. Secondary studies were evaluated for patients’ clinical outcomes. There were wide differences among the studies that assessed the effects of CPs on HF patients, with some contrasting clinical outcomes reported. Secondary studies that were non-specific for CPs and included other multidisciplinary care approaches as well showed, in some cases, a shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) compared to usual care; studies that focused on promoting early mobilization showed better outcomes of mortality, morbidity, function, or service utilization; CPs mainly based on intensive occupational therapy and/or physical therapy exercises improved functional recovery and reduced LOS, with patients also discharged to a more favorable discharge destination; CPs principally focused on early mobilization improved functional recovery. A secondary study specifically designed for CPs showed lower odds of experiencing common complications of hospitalization after HF. In conclusion, although our overview suggests that CPs can reduce significantly LOS and can have a positive impact on different outcomes, data are insufficient for formal recommendations. To properly understand the effects of CPs for HF, a systematic review is needed of primary studies that specifically examined CPs for HF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The 1.26 million hip fractures (HFs) estimated in adults for the year 1990 are predicted to rise to 7.3–21.3 million by 2050 [1]. The one-year death rate after a HF is about 20–30 %; and one-third of this excess mortality can be directly attributed to the HF itself [2]. In addition to the short-term mortality associated with HF, significant excess annual mortality persists up to 10 years or more after HF [3]. Older individuals who suffer a HF can expect a 15–25 % decline in the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL), and about 10–20 % of the fractured people will be unable to return to their previous residences and will need some type of assisted living care [4]. Even after a significant recovery during the first year, hip fracture patients continue to suffer from functional impairment and loss in quality of live at 1 year [5].

HFs correspond to the second most important cause of hospitalization in older patients [6], with elderly patients accounting for approximately 90 % of all hospital stays due to HFs [7]. Health service consumption increases significantly after hip fracture, with most of their healthcare costs owing to long-term care [8–10]. One of the key issues that frequently arise when care teams manage HF is that it is not easy to provide standard care that can reduce variations in processes of care and patient outcomes.

Care pathways (CPs) are complex interventions [11–13] and can be one of the approaches to foster better outcomes and optimal resource use [14–16]. CPs are currently used worldwide for different kinds of patient groups [17, 18].

CPs have been applied as a practice method and tool for the improvement of the care management of patients with a HF, globally one of the main causes of mortality and morbidity. Because of this reason, numerous primary and secondary literature studies about CPs for HF were published (and it is the unique case in the literature). Unfortunately, these studies seem to be not conclusive. Even though the use of CPs has been in general recommended by international guidelines in relation to the management of HF patients [19–24], no conclusive systematic overview of secondary studies is available that specifically examines the effects of CPs use on HF patients through the continuum of care.

Hence, the main objective of the present systematic overview of the literature was to identify and analyze published secondary studies of the effects of CPs on HF patients.

This overview of secondary literature studies represents an initial level of a wider literature review approach to overall investigate the available published studies assessing the effect of the use of CP for HF.

Besides the general objective of the overview, our specific research questions are the following: Are there in the literature secondary studies evaluating the effect of CPs for HF, through whose findings it is possible to achieve conclusive recommendations on the use of CP for HF? Are all the eventual secondary studies specific for CP or not, and/or are also specific for hip fracture or not? Are the primary studies included in the eventual secondary studies classifiable as CP through a unique definition of CP?

Materials and methods

Data sources

Two reviewers (FL and CL) independently searched major electronic biomedical databases for relevant articles on CPs and HF and hand searched and checked the bibliographies of identified publications. To identify secondary literature, we searched in The Cochrane Library: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR, up to 4th Quarter 2010), the Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE, up to 4th Quarter 2010), Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA database, up to 2010 Issue 4), and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED, up to 2010 Issue 4). We also searched MEDLINE–PubMed (1975–Jan 2011), Ovid EMBASE (1998–2010, Jan 2011), and CINAHL–EBSCO–host (1981–Dec 2010).

Search strategy

To obtain the best sensitivity for the searches, we did not limit the initial search by year of publication or language. However, we examined the full texts of only relevant English, German, French, Dutch, and Italian language articles. As a first strategy, the following medical subject headings (MeSH) related to CPs and HFs were used: Critical Pathways AND Hip Fractures (MEDLINE), Clinical Pathways AND Hip Fractures (EMBASE), and Critical Path AND Hip Fractures (CINAHL). Second, a combined non-MeSH and MeSH search was performed based on the following search string: (“care pathway” OR “clinical pathway” OR “critical pathway” OR “care map” OR “clinical path” OR “multidisciplinary approach”) AND (“Hip Fractures”[MeSH]). For the four searched databases included in the Cochrane Library (CDSR, DARE, HTA, NHSEED), the MeSH terms “Critical Pathways” AND “Hip Fractures” were used. When the full text of a relevant article was not found, the authors were contacted for further information. If the requested information was not available, the article was excluded.

Inclusion criteria

In order to obtain a sufficient level of evidence, we included, as secondary literature publications, other systematic overviews (SO), systematic reviews (SR), meta-analyses (MA), and health technology assessment (HTA) reports [25]. The secondary publications had to include experimental and quasi-experimental primary studies (original articles) addressing CP interventions for PFF. All studies concerning CPs were included if they had recruited patients of all ages who had been admitted to acute care hospitals, post-acute care/rehabilitation, and post-rehabilitation for HF. All studies concerning all potential outcome measures on clinical outcomes, process of care, and hospitalization costs were considered. The evidence level of the included primary studies was classified as follows: I = randomized controlled trials (RCTs); II = Cohort observational study (high evidence); IIa = Cohort observational study (moderate evidence); IIb = Cohort observational study (limited evidence); IIc = Cohort observational study (weak or unclear evidence).

To properly include secondary studies about CP in our systematic overview, the definition of care pathway according to the European Pathway Association (www.E-P-A.org) was adopted. A CP is defined as a complex intervention for the mutual decision making and organization of care processes for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period. Defining characteristics of CP include: (i) an explicit statement of the goals and key elements of care based on evidence, best practice, and patients’ expectations and their characteristics; (ii) the facilitation of the communication among the team members and with patients and families; (iii) the coordination of the care process by coordinating the roles and sequencing the activities of the multidisciplinary care team, patients, and their relatives; (iv) the documentation, monitoring, and evaluation of variances and outcomes; and (v) the identification of the appropriate resources. The aim of a CP is to enhance the quality of care across the continuum by improving risk-adjusted patient outcomes, promoting patient safety, increasing patient satisfaction, and optimizing the use of resources [16, 26].

Subsequently, to our classification of care interventions, secondary studies were also included if they dealt with other multidisciplinary care approaches (MCAs) delivered by a team. In fact, MCAs were intended to be wider holistic approaches to bridge the gap between hospital admission and discharge home, but not based on a CP. Effectively, the E-P-A definition of CP allowed the classification of CP interventions versus other, non-CP, interventions of the primary studies included in the secondary studies (Table 1).

Exclusion criteria

The explicit reasons for article exclusion were the following: (1) the article did not contain the results of any study; (2) the study was not pertinent to the research question(s); (3) the study was part of duplicate publications reporting the same main outcome measures and/or it was a study performed as a individual component of the same study not including additional results; (4) the study lacked detailed and appropriate risk-adjusted analyses; and (5) the study met the inclusion criteria but the full text was not available and the authors could not be retrieved (corresponding author/information not available).

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (FL and CL) screened all the titles, abstracts, and keywords of publications identified by the searches to assess their eligibility, according to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Publications that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded during this phase. We then obtained a complete paper copy of all potentially relevant studies and had both reviewers assess all publications according to the pre-specified selection criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with two additional researchers (MP and KV).

Methodological quality assessment of studies

Two reviewers (FL and CL) independently assessed the specificity of the pathway intervention according to the defined characteristics by E-P-A. The results are shown in Table 1. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the two additional researchers (MP and KV).

Results

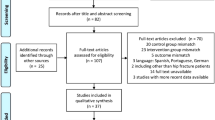

The explicit search strategy led to the initial selection of 108 records. After removing duplicate articles, 85 were considered as potentially relevant (Fig. 1). For the first stage of the study assessment, we scanned all 85 titles and abstracts for inclusion, excluding 79 non-pertinent publications. The remaining 6 potentially relevant articles were assessed as full texts.

The non-CP interventions were considered as other interventions evaluated in the secondary studies (Table 1). The SO initially included 6 pertinent publications corresponding to 6 secondary studies. Even though 6 secondary studies were identified and considered, it was not possible to include the SR and MA of Rotter et al. (2008) and the SR and MA of Rotter et al. (2010) because both studies were not HF-specific [27, 28]. In fact, these two reviews considered other conditions in addition to HF, hardly including primary HF studies in their reviews (2 and 1, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Of the four studies finally included in the SO, three evaluated CPs together with MCA interventions for HF and only one specifically addressed how CPs affect the quality of care provided to patients with HFs [29–32]. It was possible to describe the results of secondary studies only for outcome indicators, such as function, morbidity, mortality, discharge location, hospital readmission, and hospital length of stay (LOS). Such results were measured either during the entire care period (i.e., starting from the time of hospital admission through to the final rehabilitation process) or during particular phases and settings of patient care. The characteristics and results of the included studies are described in Table 2.

In an HTA report consisting of a SR and MA, Cameron et al. [29] found that, in the three primary studies included, the use of CPs (or MCAs) was associated with a shorter hospital LOS (mean reduction of 5.3 days) [33–35]. However, there was no evidence that CPs affected readmission to hospital, residential status, mortality, or morbidity. CPs did result in a non-significant increase in patients achieving independent mobility at discharge.

In the results of their SO of both primary studies and systematic reviews, Beaupre et al. [30] concluded that no clear level 1 evidence (consisting of at least one good quality RCT) existed to support the premise that CPs and MCAs with a focus on promoting early mobilization afford better outcomes in terms of mortality, morbidity, function, or service utilization than usual care [36–44]. They found that some studies suggested that CP- and MCA-standardized multidisciplinary care reduced in-hospital LOS, with an increase in LOS in other studies [36–39, 41–46].

A SR of Chyudik et al. [31] focused on CPs and MCAs in the HF rehabilitation continuum. When implemented in an acute care setting, CPs mainly based on intensive occupational therapy and/or physical therapy exercises improved functional recovery [36, 47, 48], and reduced LOS [36, 47, 49]. Patients subjected to CPs were also discharged to a more favorable discharge destination [36]. CPs principally focused on early mobilization improved functional recovery [50]. The effects of CPs on discharge location [39, 50, 51], and LOS [45, 50, 51], were conflicting. No differences were found before and after the implementation of CPs in terms of hospital readmission [45, 51] or mortality [39, 51]. Moreover, only one study found differences in functional recovery between CP patients and non-CP patients, but only after accounting for levels of social support across both groups of patients [51].

In a SR and MA of Neuman et al. [32], an association was observed between CP use and lower odd ratios (OS) of experiencing four common complications of hospitalization after HF: deep venous thrombosis [44, 45, 52, 53], pressure ulcers [44, 45, 51, 53–55], surgical site infection [44, 45, 52], and urinary tract infection [44, 45, 51–53], respectively. An association between CP use and changes in combined short-term mortality outcome (i.e., in-hospital mortality plus 30-day mortality) did not reach statistical significance [44, 45, 52–54]. Similarly, no significant differences were observed for the OS of contracting pneumonia [44, 45, 51–53, 56].

Discussion

Some different specific and not specific for CP and HF secondary literature studies are published on the topic related to CP for HF (6 were included at a first phase in the overview, and 4 were finally assessed); and this is the first known case in the literature about CP. Both a recently published Cochrane review of CP studies (2010) and a paper by Rotter et al. (2008) concluded that CPs reduce the risk of complications without having a negative impact on the organization of care [27, 28]. Although both reviews were well conducted and based on sound analyses, we were concerned about the appropriateness of the primary studies included. CPs are complex interventions. It is difficult to compare findings if study publications do not describe the intervention or context in sufficient detail [16]. In any case, one cannot use these results for a systematic review of the effects of CPs on a specific condition and/or procedure because of their lack of specificity [28, 57]. Therefore, even if we had considered both studies for our systematic overview, we would not have been able to address any specifics about the effects of CPs for HF.

As a possible limitation to our findings, it could be argued that the originality of a review of secondary literature could be limited, not being based on numeric quantities. We think that this could be generally true when analyzing highly specified interventions (a new drug, a new device, etc.). In such cases, it is possible that a review of secondary literature would not add any value to existing papers. On the contrary, in health services research are evaluated complex interventions that are a mix of different active components and that are difficult to specifically define [11–13]. Because of the lack of specific definitions, there is a risk that secondary literature on complex interventions could be seriously biased by the misclassification of the intervention because the included papers are not enough specific. This is the case of care pathways that are often confused with other similar interventions, such as the implementation of clinical guidelines, of protocols, as it has been shown in a recent literature debate [16].

Our analysis of results obtained through a specific secondary literature search revealed the issues discussed above. In fact, it was difficult to compare different studies because they lacked a common definition for CP. In addition, it was not always clear whether the results were attributable to the CPs or to some specific intervention included in the CPs. The latter probably led to the fragmentation of the CPs as complex interventions. Therefore, studies that could not attribute their results specifically to a CP itself probably did not address our main overview objective. The most specific and recent meta-analysis by Neuman et al. (2009) showed a similar problem. Neuman et al. developed their own instrument “to assess elements common to clinical pathways” that were based merely on two previous reviews [19, 50], not on actual definitions. In fact, much confusion remains about what a clinical pathway and/or a CP is and there is an urgent need to adopt a clear and strict definition for CP [16]. Indeed, because of this methodological issue, some of the individual studies included in the secondary studies may not have assessed CPs after all. Moreover, in many of the primary papers included in the secondary research that we analyzed, CPs were part of wider programs or organizational interventions, such as geriatric orthopedic rehabilitation units and multidisciplinary early-supported discharge programs [58]. In fact, in addition to CP, different other interventions (not clearly classified as CP, by E-P-A definition) are often included in the secondary studies. Mostly, the secondary studies did not clearly and completely describe the specific content of the development and implementation process of the CP intervention related to the included primary studies. Therefore, even when a CP was developed, many of the observed results could not be directly attributable to the use of the CP. Also, the study designs were substantially different in many characteristics, including typology of patients, typology of controls groups, and selected outcomes. Finally, the studies did not consider other possibly relevant measures of organization of care, health service consumption, and cost-related outcomes.

Considering all these possible limitations, the major conclusion that emerged from the secondary literature is that CPs can reduce significantly LOS and can have a positive impact on different outcomes. The results also suggest that assessments of hospital quality for HF, when primarily based on mortality, may not reveal important improvements in patient outcomes that may be achieved by using CPs.

We conclude that, although positive results emerged from the present systematic overview of secondary literature studies, the available evidence does not allow formal recommendations. Limitations included the characteristics of dissimilar populations, with differences in inclusion criteria and methods to develop and implement specific interventions, and with patient outcome measures used to assess the effect of CPs as complex interventions.

Therefore, we think that a review of secondary literature on the effect of care pathways for hip fractures is something more than a comprehensive summary of the published papers but is a useful guide to researchers and clinicians in understanding better both the definition of care pathways and their effects on patients with hip fractures. In fact, has it has been shown in Fig. 1, only four studies met inclusion criteria and have been assessed. To our knowledge, this study is the first reviews of secondary literature on the effect of care pathways for hip fractures and we think that our findings will be also of help to strengthen study design of further original reviews on the same and similar topics.

Future research should include adequately powered, multicenter studies with high-quality methodological designs. Future studies should also investigate the effects of CP interventions on patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life, their satisfaction with the interventions, teamwork, and, possibly, include cost-effectiveness outcomes. More long-term data are needed as well. Health service consumption increases dramatically after HF, with most of the excess healthcare costs related to long-term care, begging for follow-up data on the long-term journey and care of older patients.

Despite the weak findings of this overview of secondary studies, only basing on these findings, it is possible to understand some main critical methodological issues related to the secondary literature studies. In the light of these issues, there is a need for a further level of literature review approach to overall investigate the available published studies specifically addressing the effectiveness of CPs for HF. Consequently, the findings of the overview will allow to adopt a more rigorous and explicit methodology in a systematic inclusion and review of primary literature studies (original articles).

One of the research priorities is a definitive multicenter cluster randomized control trial of the impact of CPs in the in-hospital management and follow-up of HF patients.

References

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7:407–413

Parker MJ, Anand JK (1991) What is the true mortality of hip fractures? Public Health 105:443–446

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152(6):380–390

Rosell PAE, Parker MJ (2003) Functional outcome after hip fracture: a 1-year prospective outcome study of 275 patients. Injury 34:529–532

Boonen S, Autier P, Barette M, Vanderschueren D, Lips P, Haentjens P (2004) Functional outcome and quality of life following hip fracture in elderly women: a prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int 15:87–94

Wilkins K (1999) Health care consequences of falls for seniors. Health Rep 10:47–55

AHRQ News and Numbers, January 4, (2006) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/news/nn/nn010406.htm

Brainsky A, Glick H, Lydick E et al (1997) The economic cost of hip fractures in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 45:281–287

Haentjens P, Autier P, Barette M, Boonen S (2001) The economic cost of hip fractures among elderly women: a one-year, prospective, observational cohort study with matched-pair analysis. J Bone Jt Surg Am 83:493–500

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Papadimitropoulos E (2001) Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:271–278

Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D et al (2000) Framework for the design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 321:694–696

Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J et al (2007) Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 334:455–459

Medical Research Council (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. MRC. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance

Pearson SD, Goulart-Fisher D, Lee TH (1995) Critical pathways as a strategy for improving care: problems and potential. Ann Intern Med 123:941–948

Panella M, Marchisio S, Di Stanislao F (2003) Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: do pathways work? Int J Qual Health Care 15:509–521

Vanhaecht K, Ovretveit J, Elliott MJ, Sermeus W, Ellershaw JE, Panella M (2011) have we drawn the wrong conclusions about the value of care pathways? Is a Cochrane review appropriate? Eval Health Prof [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1177/0163278711408293

Hindle D, Yazbeck AM (2005) Clinical pathways in 17 European Union countries: a purposive survey. Aust Health Rev 29:94–104

Vanhaecht K, Bollmann M, Bower K, Gallagher C, Gardini A, Guezo J, Jansen U, Massoud R, Moody K, Sermeus W, Van Zelm RT, Whittle CL, Yazbeck AM, Zander K, Panella M (2006) Prevalence and use of clinical pathways in 23 countries—an international survey by the European Pathway Association E-P-A.org. J Integr Care Pathw 10:28–34

Chilov MN, Cameron ID, March LM (2003) Evidence-based guidelines for fixing broken hips: an update. Med J Aust 179:489–493

New Zealand Guidelines Group (2003) Acute management and immediate rehabilitation after hip fracture amongst people aged 65 years and over. New Zealand Guidelines Group, Wellington

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2006) Prevention and management of hip fracture in older people. SIGN guideline 56. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Edinburgh

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2009) Management of hip fracture in older people. SIGN guideline no. 111. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Edinburgh

Mak JC, Cameron ID, March LM, National Health and Medical Research Council (2010) Evidence-based guidelines for the management of hip fractures in older persons: an update. Med J Aust 192(1):37–41

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) Hip fracture the management of hip fracture in adults. NICE clinical guideline 124. Developed by the National Clinical Guideline Centre

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors) (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. [Overviews of Reviews (Chapter 22, Section 3)]. The Cochrane collaboration. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org

Vanhaecht K, De Witte K, Sermeus W (2007) The impact of clinical pathways on the organisation of care processes. ACCO, Leuven; https://lirias.kuleuven.be/bitstream/123456789/252816/1/PhD+Kris+Vanhaech

Rotter T, Kugler J, Koch R, Gothe H, Twork S, van Oostrum JM, Steyerberg EW (2008) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of clinical pathways on length of stay, hospital costs and patient outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res 8:265

Rotter T, Koch R, Kugler J, Gothe H, Kinsman L, James E (2010) Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3). Art no CD006632. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006632.pub2

Cameron I, Crotty M, Currie C, Finnegan T, Gillespie L, Gillespie W et al (2000) Geriatric rehabilitation following fractures in older people: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 4(2):1–110. http://www.hta.ac.uk

Beaupre LA, Jones CA, Saunders LD, Johnston DWC, Buckingham J, Majumdar SR (2005) Best practices for elderly hip fracture patients. J Gen Intern Med 20:1019–1025

Chudyk AM, Jutai JW, Petrella RJ, Speechley M (2009) Systematic review of hip fracture rehabilitation practices in the elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90(2):246–262

Neuman MD, Archan S, Karlawish JH, Schwartz JS, Fleisher LA (2009) The relationship between short-term mortality and quality of care for hip fracture: a meta-analysis of clinical pathways for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(11):2046–2054

Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Botsford DJ, Hawker RW (1993) Elderly patients with hip fractures: improved outcome with the use of care maps with high-quality medical and nursing protocols. J Orthop Trauma 7(5):428–437

Pachter S, Flics SS (1987) Integrated care of patients with fractured hip by nursing and physical therapy. NLN Publ (20–2191):441–443

Tallis G, Balla JI (1995) Critical path analysis for the management of fractured neck of femur. Aust J Public Health 19(2):155–159

Cameron ID, Lyle DM, Quine S (1993) Accelerated rehabilitation after proximal femoral fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil 15(1):29–34

Galvard H, Samuelsson SM (1995) Orthopedic or geriatric rehabilitation of hip fracture patients: a prospective, randomized, clinically controlled study in Malmo, Sweden. Aging 7:11–16

Swanson CE, Day GA, Yelland CE et al (1998) The management of elderly patients with femoral fractures. A randomised controlled trial of early intervention versus standard care. Med J Aust 169:515–518

March LM, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Chamberlain AC, Schwarz JM, Brnabic AJ, O’Meara P, Taylor TF, Riley S, Sambrook PN (2000) Mortality and morbidity after hip fracture: can evidence based clinical pathways make a difference? J Rheumatol 27(9):2227–2231

Cameron I, Handoll H, Finnegan T, Madhok R, Langhorne P (2001) Co-ordinated multidisciplinary approaches for inpatient rehabilitation of older patients with proximal femoral fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3). Art no CD000106. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000106

Huusko TM, Karppi P, Avikainen V, Kautiainen H, Sulkava R (2002) Intensive geriatric rehabilitation of hip fracture patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Orthop Scand 73:425–431

Naglie G, Tansey C, Kirkland JL et al (2002) Interdisciplinary inpatient care for elderly people with hip fracture: a randomized control trial. Can Med Assoc J 167:25–32

Hagsten B, Svensson O, Gardulf A (2004) Early individualized postoperative occupational therapy training in 100 patients improves ADL after hip fracture: a randomized trial. Acta Orthop Scand 75:177–183

Roberts HC, Pickering RM, Onslow E, Clancy M, Powell J, Roberts A, Hughes K, Coulson D, Bray J (2004) The effectiveness of implementing a care pathway for femoral neck fracture in older people: a prospective controlled before and after study. Age Ageing 33(2):178–184

Choong PF, Langford AK, Dowsey MM, Santamaria NM (2000) Clinical pathway for fractured neck of femur: a prospective, controlled study. Med J Aust 172(9):423–426

Huusko TM, Karppi P, Avikainen V, Kautiainen H, Sulkava R (2000) Randomised, clinically controlled trial of intensive geriatric rehabilitation in patients with hip fracture: subgroup analysis of patients with dementia. BMJ 321(34 ref):1107–1111

Jette AM, Harris BA, Cleary PD, Campion EW (1987) Functional recovery after hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 68:735–740

Swanson CE, Yelland CE, Day GA (2000) Clinical pathways and fractured neck of femur. Med J Aust 172(9):415–416

Koval KJ, Chen AL, Aharonoff GB, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD (2004) Clinical pathway for hip fractures in the elderly: the hospital for joint diseases experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res (425):72–81

Beaupre LA, Cinats JG, Senthilselvan A, Scharfenberger A, Johnston DW, Saunders LD (2005) Does standardized rehabilitation and discharge planning improve functional recovery in elderly patients with hip fracture? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86(12):2231–2239

Beaupre LA, Cinats JG, Senthilselvan A, Lier D, Jones CA, Scharfenberger A, Johnston DWD, Saunders LD (2006) Reduced morbidity for elderly patients with a hip fracture after implementation of a perioperative evidence-based clinical pathway. Qual Saf Health Care 15(5):375–940

Rasmussen S, Kristensen B, Foldager S et al (2003) Accelereret operationsforlob efter hofterfraktur. Ugeskr Laeger 165:29–33

Khasraghi FA, Christmas C, Lee EJ et al (2005) Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary team approach to hip fracture management. J Surg Orthop Adv 14:27–31

Olsson LE, Karlsson J, Ekman I (2006) The integrated care pathway reduced the number of hospital days by half: a prospective comparative study of patients with acute hip fracture. J Orthop Surg Res 1:3

Hommel A, Bjorkelund KB, Thorngren K, Ulander K (2007) A study of a pathway to reduce pressure ulcers for patients with a hip fracture. J Orthop Nurs 11(3–4):151–159

Moran WP, Chen GJ, Watters C et al (2006) Using a collaborative approach to reduce postoperative complications for hip-fracture patients: a three-year follow-up. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 32:16–23

Gotzsche PC (2000) Why we need a broad perspective on meta-analysis. BMJ 321:585–586

Giusti A, Barone A, Razzano M, Pizzonia M, Pioli G (2011) Optimal setting and care organization in the management of older adults with hip fracture. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 47(2):281–296 (Epub review)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the European Pathway Association (www.E-P-A.org) through an unrestricted educational grant from PFIZER. We hereby acknowledge PFIZER BELGIUM, PFIZER ITALY, PFIZER IRELAND, AND PFIZER PORTUGAL for providing the unrestricted educational grant. The funding sources played no role in the design, execution, and evaluation of the present study. Fabrizio Leigheb got from European Pathway Association an unrestricted educational grant of about € 16,000 granted for 3 consecutive years of PhD course (2009–2011) at the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine (from year 2012 established and renamed as the Department of Translational Medicine) of the University of Eastern Piedmont “Amedeo Avogadro,” Novara, Italy.

Conflict of interest

The authors of the present manuscript, Fabrizio Leigheb, Kris Vanhaecht, Walter Sermeus, Cathy Lodewijckx, Svin Deneckere, Steven Boonen, Paulo A Boto, Rita Veloso Mendes, and Massimiliano Panella, declare that they have not proprietary interest or conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leigheb, F., Vanhaecht, K., Sermeus, W. et al. The effect of care pathways for hip fractures: a systematic overview of secondary studies. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 23, 737–745 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-012-1085-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-012-1085-x