Abstract

Background

An international panel achieved consensus on 9 need-based and 2 time-based major referral criteria to identify patients appropriate for outpatient palliative care referral. To better understand the operational characteristics of these criteria, we examined the proportion and timing of patients who met these referral criteria at our Supportive Care Clinic.

Methods

We retrieved data on consecutive patients with advanced cancer who were referred to our Supportive Care Clinic between January 1, 2016, and February 18, 2016. We examined the proportion of patients who met each major criteria and its timing.

Results

Among 200 patients (mean age 60, 53% female), the median overall survival from outpatient palliative care referral was 14 (95% confidence interval 9.2, 17.5) months. A majority (n = 170, 85%) of patients met at least 1 major criteria; specifically, 28%, 30%, 20%, and 8% met 1, 2, 3, and ≥ 4 criteria, respectively. The most commonly met need-based criteria were severe physical symptoms (n = 140, 70%), emotional symptoms (n = 36, 18%), decision-making needs (n = 26, 13%), and brain/leptomeningeal metastases (n = 25, 13%). For time-based criteria, 54 (27%) were referred within 3 months of diagnosis of advanced cancer and 63 (32%) after progression from ≥ 2 lines of palliative systemic therapy. The median duration from patient first meeting any criterion to palliative care referral was 2.4 (interquartile range 0.1, 8.6) months.

Conclusions

Patients were referred early to our palliative care clinic and a vast majority (85%) of them met at least one major criteria. Standardized referral based on these criteria may facilitate even earlier referral.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer patients often experience significant physical and psychological distress, and are faced with many difficult decisions regarding cancer treatments and care planning [9, 28]. Timely involvement of palliative care into oncologic care has been found to improve patients’ quality of life, symptom burden, mood, and quality of end-of-life care [7, 8, 15, 22]. Multiple professional organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) have endorsed timely palliative care referral for cancer patients [6, 25, 31]. However, there remains significant heterogeneity among clinicians in deciding who should be referred to palliative care and when is the most appropriate time [19], which likely contributed to the inconsistent and delayed referrals [16, 17].

To optimize use of the scarce palliative care resources and standardize care, a panel of international experts on palliative cancer care developed a consensus list of criteria for outpatient palliative care referral for patients with advanced cancer seen at secondary/tertiary care hospitals [18]. This consensual list consisted of 9 needs-based criteria and 2 time-based criteria; however, these criteria have not been tested empirically. A better understanding of operational characteristics of these referral criteria may facilitate their application in clinical practice and identify opportunities for refinement. In this retrospective study, we determined the proportion of patients referred to palliative care who met the major referral criteria. We also determined when these standardized referral criteria were first met to highlight opportunities for earlier referral.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

In this retrospective study, we included consecutive patients with advanced cancer (i.e., locally advanced, metastatic, or recurrent) who were seen at the Supportive Care Outpatient Clinic at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) for consultation between January 1, 2016, and February 18, 2016. By focusing on patients who were already referred to palliative care, we were able to examine the relative timing of referral based on criteria as compared to actual practice. The institutional Review Board at the MDACC reviewed and approved this study with waiver for informed consent.

Outpatient supportive care clinic

The outpatient clinic and referral pattern have been described in detail elsewhere [4, 12, 16]. Briefly, this clinic operates 5 days a week and is regularly staffed by an interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, psychologists, counselors, and a pharmacist. Other professionals such as social workers, chaplains, child life counselors, dieticians, and physical therapists are available on an as needed basis. In 2018, there were 1772 new patient consultations and 6943 follow-up visits. The mean time from referral to consultation was 10.6 days.

Data collection

We reviewed the electronic medical records and collected data on baseline demographics at the time of outpatient palliative care consultation, including age, sex, race, cancer diagnosis, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and CAGE questionnaire. The CAGE questionnaire has been validated for screening of alcohol-related disorders [5]. It consists of 4 questions (“Cut down,” “Annoyed,” “Guilty,” and “Eye opener”) with a score of 2 or greater indicating a risk of alcoholism [23].

We also conducted symptom distress screening with the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS). This is a 12-item numeric rating scale that examines the average symptom intensity over the past 24 h, including pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, dyspnea, poor appetite, poor well-being, insomnia, financial distress, and spiritual distress. Each item was rated using a numeric rating scale that ranges from 0 (none) to 10 (worst possible). A score of 7 or higher was considered as “severe” [21, 27, 30]. ESAS has been widely used in clinical practice and validated in multiple clinical settings [11].

We determined if patients met each of the 11 major criteria within 30 days of the palliative care consultation [18]. Each criterion was coded in a binary manner (yes or no). We also reviewed the chart from the time of diagnosis of advanced cancer and captured the date that these criteria were first met (if applicable). The operational definition for each criteria is shown below:

- 1.

Severe physical symptom(s)—documentation of severe pain, dyspnea, nausea, or other physical symptoms, such as an intensity of ≥ 7/10 on the ESAS both at the time of palliative care consultation and prior to that visit

- 2.

Severe emotional symptom(s)—date of documentation of severe depression or anxiety, such as an intensity of ≥ 7/10 on ESAS both at the time of palliative care consultation and prior to that visit

- 3.

Request for hastened death—date of documentation of suicidal intent or ideation both at the time of palliative care consultation and prior to that visit

- 4.

Spiritual or existential crisis—documentation of severe spiritual pain, such as an intensity of ≥ 7/10 on ESAS or description by chaplain both at the time of palliative care consultation and prior to that visit

- 5.

Assistance with decision-making/care planning—documentation that patients requested for addition assistance with cancer treatment decision-making or advance care planning both at the time of palliative care consultation and prior to that visit

- 6.

Patient request—documentation that patients requested specifically for palliative care referral anytime prior to palliative care consultation

- 7.

Delirium—date of documentation of clinical diagnosis of delirium or Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) > 13/30 palliative care consultation both at the time of palliative care consultation and prior to that visit. The MDAS is a validated scale that assesses the severity of delirium [2, 24]. It consists of 10-items based on clinical observations and interview of the patient. Each item is assigned a score from 0 to 3, with a higher score indicating greater severity. A total score of 13/30 supports the diagnosis of delirium [2].

- 8.

Brain or leptomeningeal metastases—radiologic or clinical diagnosis of cancer involvement in the brain or leptomeninges prior to palliative care consultation. Patients with central nervous system tumors were coded as yes.

- 9.

Spinal cord compression or cauda equina—radiologic or clinical diagnosis of impending or symptomatic spinal cord compression or cauda equine syndrome prior to palliative care consultation

- 10.

Within 3 months of diagnosis of advanced/incurable cancer for patients with median survival 1 year or less—palliative care consultation occurred within 90 days from date of diagnosis of advanced cancer. For coding purposes, we defined a list of malignancies with expected survival of 1 year or less from time of diagnosis based on the medical literature, including metastatic lung cancer, metastatic non-colorectal gastrointestinal cancers, metastatic anaplastic thyroid cancer, metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, metastatic renal cell carcinoma, metastatic head and neck cancer, metastatic cancer of unknown primary, locally advanced pancreatic cancer, locally advanced anaplastic thyroid cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia.

- 11.

Progressive disease despite second line palliative systemic therapy—palliative care consultation relative to the date of documentation of progression from second line treatment.

We classified the criteria into 2 categories: need-based criteria (#1–#9) and time-based criteria (#10–#11). Need-based criteria were further sub-classified into distress criteria (#1–#4), support criteria (#5–#6), and neurological criteria (#7–#9) [18].

We also collected survival data based on the last date of follow-up and vital status from cancer registry and the electronic health records.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective of this study was to determine the proportion of patients referred to palliative care who met the standardized referral criteria. We hypothesized that at least 80% of patients referred to palliative care would meet at least 1 standardized referral criterion. With 200 patients, we calculated that we could estimate the proportion of patients referred to palliative care who met at least 1 standardized referral criterion with a standard error of < 3%.

The baseline patient demographics and ESAS were summarized using standard descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, range, interquartile range (IQR), and frequency. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the median time from time of meeting criterion to death and its 95% confidence intervals. Overall survival was calculated either from the time of palliative care consultation or when the referral criteria were met.

The Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline patient characteristics at time of outpatient palliative care consultation are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 60; 106 (53%) were female and 127 (64%) were non-Hispanic White. The most common cancer diagnoses were respiratory (n = 36, 18%) and gastrointestinal (n = 36, 18%). A majority of patients had a diagnosis of metastatic disease (n = 111, 56%). Pain, fatigue, and insomnia were the symptoms with the highest intensity.

The median interval from first oncology consultation to outpatient palliative consultation was 5.3 months (interquartile range 1.2, 21 months). The median overall survival from palliative care consultation was 14 months (95% CI 9.2, 17.5 months).

Proportion of patients who met referral criteria at the time of palliative care consultation

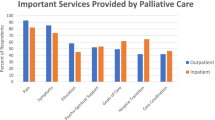

For need-based criteria, severe physical distress was the most commonly met at the time of palliative care consultation (n = 140, 70%), followed by severe emotional distress (n = 36, 18%), assistance with decision-making/care planning (n = 26, 13%) and brain or leptomeningeal metastases (n = 25, 13%) (Table 2). Four criteria (request for hastened death, spiritual crisis, patient request for palliative care referral, and delirium) were met in ≤ 2% patients.

For time-based criteria, 54 (27%) were referred within 3 months of diagnosis of advanced cancer and 63 (32%) after progression from ≥ 2 lines of palliative systemic therapy.

Overall, 170 (85%) met at least one major criteria at the time of palliative care referral (Fig. 1).

Timing when major referral criteria were first met

Table 3 shows that the median time from first documentation of severe physical or emotional symptoms to referral was generally within 1 month. In contrast, the median interval was 3.6 to 4.6 months between neurological involvement and palliative care referral. Similarly, the median interval was 4.3 months for “within 3 months of diagnosis of advanced cancer” and 4.1 months for “progressive disease despite second line systemic therapy”.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, a vast majority (85%) of patients referred to our palliative care outpatient clinic met at least one of the 11 major criteria, supporting the applicability at these criteria in clinical practice. The most commonly met criteria were related to symptom distress, while several criteria were rarely met. We also identified that a subset of these criteria were met prior to palliative care consultation, suggesting an opportunity for earlier referral if these criteria were systematically applied.

We found that severe physical and emotional distress was a key trigger for oncologists to refer patients to palliative care. This is reflected by the observation that 70% and 18% of patients had severe physical and emotional ESAS intensity at the time of palliative care consultation. Implementation of routine symptom distress screening as mandated by the Commission on Cancer likely enhanced oncologists’ awareness of symptom burden and is associated with improved outcomes [1, 21]. Oncologists can address some common symptoms in the front line; at the same time, referral to palliative care has been found to further improve quality of life, mood, and symptom control over oncologic care alone in randomized trials [7, 8, 15, 22]. Our data suggest that oncologists recognize the role of palliative care in optimizing symptom control.

Interestingly, several criteria were less often met, including delirium, request for hastened death, spiritual crisis, and patient request for palliative care referral. For example, many patients are either unaware of palliative care or confused about its role [26]. They often rely on their oncologists to suggest an appropriate referral. We believe that these criteria remain important because they clearly indicate a need for further support if present.

We also examined the time interval when each patient first met each criterion in relation to their palliative care consultation. Our findings highlighted that clinicians were referring patients based on symptoms with limited delay; in contrast, they were less likely to be referred immediately when meeting the neurological involvement criteria and time-based criteria. Our data suggest that if patients were referred based on these criteria, they would be seen by palliative care clinic approximately 4 months earlier. Importantly, our patients were relatively unique because they were already referred quite early in the disease trajectory (i.e., > 1 year overall survival from time of consultation) relative to many other institutions [3, 13, 14, 32].

Standardized referral based on these criteria may facilitate even earlier referral for these patients [10, 18, 20]. Earlier referral may be beneficial; however, many palliative care programs may not be able to handle to increased workload [29]. Individual institutions would need to decide which criteria subset should be adopted and/or modified—symptom, neurological, or time-based criteria [15].

This study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center study involving a tertiary care cancer center. The patient population and oncologist characteristics may not be generalizable to other settings. Furthermore, our center has a large palliative care service and patients were already referred relatively early [13, 14, 32]. Thus, future studies should examine these criteria in other settings. Second, this is a retrospective study and data collection was dependent on the quality of documentation in the electronic medical records. Third, the focus of this study was on patients already referred to palliative care to assess how the timing of the criteria compared to actual practice. Future research should examine the operational characteristics in oncology setting. Fourth, we were only able to assess whether patients met each criterion and could not ascertain whether patients were actually referred because of them, partly because the reason for referral was not well documented. A prospective study is required to examine this question. Fifth, only the major referral criteria based on Delphi consensus were assessed in this study [18]. Because referral criteria should ultimately be tailored to each institution, a different set of criteria may be considered in other settings.

In summary, we found that a large proportion (85%) of patients referred to our palliative care outpatient clinic met at least one major criteria, supporting the applicability of the major referral criteria. Our study also highlighted that neurological and time-based criteria were less likely used to trigger a referral; standardized referral based on these criteria may facilitate even earlier referral. Future studies should assess the applicability of these criteria in oncology clinics and whether automatic referral could result in targeted referrals and improved patient outcomes.

References

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, Rogak L, Bennett AV, Dueck AC, Atkinson TM, Chou JF, Dulko D, Sit L, Barz A, Novotny P, Fruscione M, Sloan JA, Schrag D (2016) Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34(6):557–565

Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S (1997) The memorial delirium assessment scale. J Pain Symptom Manag 13(3):128–137

Calton BA, Alvarez-Perez A, Portman DG, Ramchandran KJ, Sugalski J, Rabow MW (2016) The current state of palliative care for patients cared for at leading US cancer centers: the 2015 NCCN palliative care survey. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 14(7):859–866

Dalal S, Bruera S, Hui D, Yennu S, Dev R, Williams J, Masoni C, Ihenacho I, Obasi E, Bruera E (2016) Use of palliative care services in a tertiary cancer center. Oncologist 21(1):110–118

Ewing JA (1984) Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 252(14):1905–1907

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Firn JI, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Phillips T, Stovall EL, Zimmermann C, Smith TJ (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 35(1):96–112

Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, Antes G, Meffert C, Xander C, Stock S, Mueller D, Schwarzer G, Becker G (2017) Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 357:j2925

Haun MW, Estel S, Rucker G, Friederich HC, Villalobos M, Thomas M, Hartmann M (2017) Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:Cd011129

Hui D (2014) Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol 26(4):372–379

Hui D, Bruera E (2016) Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 13(3):159–171

Hui D, Bruera E (2017) The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: past, present and future developments. J Pain Symp Manage 53(3):630–643

Hui D, Bruera E (2019) Models of palliative care delivery for cancer patients. J Clin Oncol

Hui D, Cherny N, Latino N, Strasser F (2017) The ‘critical mass’ survey of palliative care programme at ESMO designated centres of integrated oncology and palliative care. Ann Oncol 28(9):2057–2066

Hui D, Cherny NI, Wu J, Liu D, Latino NJ, Strasser F (2018) Indicators of integration at ESMO designated centres of integrated oncology and palliative care. ESMO Open 3(5):e000372

Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, Bruera E (2018) Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin 68(5):356–376

Hui D, Kilgore K, Park M, Liu D, Kim YJ, Park JC, Fossella F, Bruera E (2018) Pattern and predictors of outpatient palliative care referral among thoracic medical oncologists. Oncologist 23(10):1230–1235

Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, Tanco KC, Zhang T, Kang JH, Rhondali W, Chisholm G, Bruera E (2012) Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 17(12):1574–1580

Hui D, Masanori M, Watanabe S, Caraceni A, Strasser F, Saarto T, Cherny N, Glare P, Kaasa S, Bruera E (2016) Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 17(12):e552–e559

Hui D, Meng YC, Bruera S, Geng Y, Hutchins R, Mori M, Strasser F, Bruera E (2016) Referral criteria for outpatient palliative cancer care: a systematic review. Oncologist 21(7):895–901

Hui D, Mori M, Meng YC, Watanabe SM, Caraceni A, Strasser F, Saarto T, Cherny N, Glare P, Kaasa S, Bruera E (2018) Automatic referral to standardize palliative care access: an international Delphi survey. Support Care Cancer 26(1):175–180

Hui D, Titus A, Curtis T, Ho-Nguyen VT, Frederickson D, Wray C, Granville T, Bruera E, McKee DK, Rieber A (2017) Implementation of the Edmonton symptom assessment system for symptom distress screening at a community cancer center: a pilot program. Oncologist 22(8):995–1001

Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, Dionne-Odom JN, Ernecoff NC, Hanmer J, Hoydich ZP, Ikejiani DZ, Klein-Fedyshin M, Zimmermann C, Morton SC, Arnold RM, Heller L, Schenker Y (2016) Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316(20):2104–2114

Kim YJ, Dev R, Reddy A, Hui D, Tanco K, Park M, Liu D, Williams J, Bruera E (2016) Association between tobacco use, symptom expression, and alcohol and illicit drug use in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 51(4):762–768

Lawlor PG, Nekolaichuk C, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, Pereira JL, Bruera ED (2000) Clinical utility, factor analysis, and further validation of the memorial delirium assessment scale in patients with advanced cancer: assessing delirium in advanced cancer. Cancer 88(12):2859–2867

Dans M, Smith T, Back A, Baker JN, Bauman JR, Beck A, Block S, Campbell T, Case AA, Dalal S, Edwards H, Fitch TR, Kapo J, Kutner JS, Kvale E, Miller C, Misra S, Mitchell W, Portman DG, Spiegel D, Sutton L, Suzumilowicz E, Temel J, Tickoo R, Urba SG, Weinstein E, Zachariah F, Bergman MA, Scavone JL (2017) Palliative care, version 2.2017 featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 15(8):989–997

Maciasz RM, Arnold RM, Chu E, Park SY, White DB, Vater LB, Schenker Y (2013) Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Support Care Cancer 21(12):3411–3419

Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC (2013) Cut points on 0-10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 45(6):1083–1093

Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P (2000) The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Support Care Rev Group Cancer 88(1):226–237

Schenker Y, Arnold R (2017) Toward palliative care for all patients with advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 3(11):1459–1460

Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, Do R, Moravan V, Myers J, Chow E (2010) A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton symptom assessment system. J Pain Symptom Manag 39(2):241–249

Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Ferrell BR, Loscalzo M, Meier DE, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Somerfield M, Stovall E, Von Roenn JH (2012) American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 30(8):880–887

Wong A, Hui D, Epner M, Balankari VR, De la Cruz V, Frisbee-Hume S, Cantu H, Zapata KP, Liu DD, Williams JL, Bruera E (2017) Advanced cancer patients’ self-reported perception of timeliness of their referral to outpatient supportive/palliative care and their survival data. J Clin Oncol 35(15S):10121–10121

Funding

DH is supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants (1R01CA214960-01A1, 1R01CA225701-01A1, R21NR016736). DH is also supported by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research (MRSG-14-1418-01-CCE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hui, D., Anderson, L., Tang, M. et al. Examination of referral criteria for outpatient palliative care among patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 28, 295–301 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04811-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04811-3