Abstract

Purpose

Early palliative care (PC) for individuals with advanced cancer improves patient and family outcomes and experience. However, it is unknown when, why, and how in an outpatient setting individuals with stage IV cancer are referred to PC.

Methods

At a large multi-specialty group in the USA with outpatient PC implemented beginning in 2011, clinical records were used to identify adults diagnosed with stage IV cancer after January 1, 2012 and deceased by December 31, 2017 and their PC referrals and hospice use. In-depth interviews were also conducted with 25 members of medical oncology, gynecological oncology, and PC teams and thematically analyzed.

Results

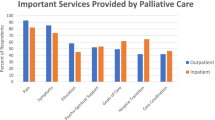

A total of 705 individuals were diagnosed and died between 2012 and 2017: of these, 332 (47%) were referred to PC, with 48.5% referred early (within 60 days of diagnosis). Among referred patients, 79% received hospice care, versus 55% among patients not referred. Oncologists varied dramatically in their rates of referral to PC. Interviews revealed four referral pathways: early referrals, referrals without active anti-cancer treatment, problem-based referrals, and late referrals (when stopping treatment). Participants described PC’s benefits as enhancing pain/symptom management, advance care planning, transitions to hospice, end-of-life experiences, a larger team, and more flexible patient care. Challenges reported included variation in oncologist practices, patient fears and misconceptions, and access to PC teams.

Conclusion

We found high rates of use and appreciation of PC. However, interviews revealed that exclusively focusing on rates of referrals may obscure how referrals vary in timing, reason for referral, and usefulness to patients, families, and clinical teams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Palliative care (PC) programs have experienced dramatic growth. In the USA, as of 2019, 72% of hospitals with fifty or more beds offered PC [5], with an increasing emphasis on integrating PC upstream in the outpatient setting [29, 32, 35]. Research shows that early introduction of PC leads to improved patient experience and quality of life [16, 20, 38, 44], less aggressive care at the end of life [17, 20, 35], and longer survival [2, 37, 39]. One study found that 57% of patients with stage IIIB and IV lung cancer in the Veterans Affairs health care system received inpatient or outpatient palliative care [37]. However, estimates suggest 60% of patients who would benefit from PC do not receive it [7]. The American Society for Clinical Oncology’s 2012 provisional opinion called for initiation of PC at the time of diagnosis for patients with advanced cancer [36], and a 2017 update recommended involving PC teams within 8 weeks of diagnosis [13]. The 2017 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend determining needs for specialist palliative care when a patient’s prognosis is in the “months to years” range [9].

In oncology practices with embedded PC teams, research has demonstrated high oncologist satisfaction with PC, time savings for oncologists, and improved patient symptoms [33]. However, referring patients to PC teams soon after diagnosis when many patients are overwhelmed emotionally and logistically presents challenges [4, 25]. Physician experiences and beliefs may vary and influence their actual referral patterns [12, 25, 28]. A 2009 study surveying 170 primary care physicians found years of work experience and personal experience with PC was associated with more referrals [1].

There is little clarity about when, why, and how individuals are referred to PC in real-world community settings. The literature is sparse, and published referral rates range from 5% [43] to 75% [10]. The primary aim of this mixed methods project was to understand palliative care referrals through the following: (a) examining rates of referral to outpatient PC and hospice use for patients with stage IV cancer and (b) exploring reasons for referral to PC through in-depth interviews with oncology and PC teams.

Methods

The study took place at a large multi-specialty group in Northern California where an outpatient PC program was rolled out across four geographic areas between 2011 and 2014.

Electronic health record data

Data were retrieved from the Epic electronic health record (EHR) and linked to organizational tumor registry data for adult patients with a stage IV cancer diagnosed after January 1, 2012 who died before December 31, 2017. Referrals to PC were placed by oncologists or other physicians and were included if they occurred any time from 30 days prior to diagnosis until death. The first referral date was used if there were multiple referrals. Referrals from 30 days prior to diagnosis to 60 days after diagnosis were defined as “early.” Referrals to community hospice programs were not logged in structured fields in the EHR, so progress notes from any clinical encounter or specialty containing the word “hospice” were extracted and reviewed. If notes confirmed the patient received or died under hospice care, the patient was categorized as using hospice. When notes were unclear, two additional team members reviewed them and determined hospice utilization status.

Organizational tumor registry data included diagnosis date and tumor site group based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) group definitions. Death date was based on Social Security Administration (SSA) death file data and information entered into the EHR by providers. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as healthcare utilization were retrieved from the EHR. Primary oncologist was defined as the medical oncology or gynecological oncology physician the patient visited most frequently, and geographic division was this physician’s location.

Provider data included specialty, geographic division, and rate of referral (patients referred to PC divided by all deceased stage IV patients seen by that provider). Referral rates were calculated for oncology providers who saw 10 or more patients during the study time period. To determine whether patients with short survival were being transferred directly to hospice care, we calculated the number of patients who died within 180 days of diagnosis and received hospice care. There are many differences across the four medical oncology geographic regions. Region A was the first to launch PC in 2011 and is the only region with offices for PC and medical oncology in the same office suite. Region D was the final area to launch PC in 2014. Gynecological Oncology providers are reported as a separate group.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were calculated; mean or median is reported (median for continuous variables which are right-skewed), along with the 10th and 90th percentile. T tests and chi-square tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, to compare early referral and later referral groups. Data management and analysis was conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1.

Interviews with clinical teams

In-depth interviews were conducted with members of teams managing these patients’ cancer care in medical oncology or gynecological oncology and PC teams. A stratified sample of participants was recruited by specialty and role, through e-mailed invitations. Interviews occurred between September 2018 and April 2019 and included questions asking when, why, and how patients with stage IV cancer should be referred to the PC team (see Appendix 1). All participants provided informed consent and received a $50 gift card. The researchers were embedded within the healthcare organization; the two researchers conducting interviews were a sociologist and public health researcher and were joined in coding by another researcher trained in qualitative methods. They adopted a constructivist approach to the analysis with the understanding that learning would result from the interaction between interview participants and researchers [6]. This research was approved by the health system’s institutional review board.

Audio recordings of interviews were transcribed and imported into qualitative data analysis software (Dedoose version 8.2.14). Given the exploratory nature of this study, we adopted a grounded theory approach to analysis [15]. Two coders began analysis using both inductive and deductive techniques, i.e., capturing emerging ideas related to palliative care referral and identifying themes revealed in previous research. The team collaboratively developed a codebook, which was finalized after reaching saturation with themes relating to PC referral [18]. Each transcript was coded by one individual and then reviewed and recoded by another coder, with weekly meetings to reach consensus on coding questions and discuss emergent findings. Qualitative methods are reported following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting guidelines [34].

Results

Palliative care referrals and hospice use

A total of 1334 patients were diagnosed with a stage IV cancer in this 6-year time period, and 705 (52.8%) died, with median survival from diagnosis of 250 days (about 8 months), 10th percentile 50 days and 90th percentile 858 days (Table 1). Of these 705 patients, 332 (47.1%) were referred to PC, and 257 (77.4%) had 1 or more PC visits. Of those referred, 161 (48.5%) were referred “early” (no later than 60 days after diagnosis). Overall, 52% of early referrals came from geographic region A (the first site to launch PC and with shared office space) even though it accounted for only 24% of the patients. Median time from diagnosis to referral was 15 days for early referrals (10th percentile 1, 90th percentile 46) versus 264 days for later referrals (10th percentile 76, 90th percentile 766) (p < 0.001). Median survival from diagnosis for early referrals was about 4 months (123 days, 10th percentile 35, 90th percentile 568), versus 14 months (422 days, 10th percentile 161, 90th percentile 1007) for those with later referrals and 7.5 months (224 days, 10th percentile 39, 90th percentile 839) for those never referred (p < 0.001). Referrals increased from 21 (6.3%) in 2012 to 89 (26.8%) in 2017 (not shown). Of 705 patients, 580 (82.3%) had notes referencing “hospice,” and 468 (66.4%) had clearly received hospice care. For 36 patients, the notes were ambiguous and were classified as not receiving hospice care. Of patients referred to PC, 263 (79%) received hospice care versus 205 (55%) of patients without PC referral.

Of all PC referrals, 71% were made by medical oncology or gynecological oncology providers, 12% by primary care providers, and 17% by other providers, e.g. hospitalists. Referral rates for 26 oncology providers (oncologists, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) who saw at least 10 patients varied from 0 to 72% (mean = 19%) (Appendix 2). Six providers referred less than 5% of patients seen; one referred 72% of 92 patients seen, and 46/66 (70%) of these were early referrals. Another referred 43% of 117 patients with 21/50 (42%) being early referrals.

We speculated that patients not expecting to live long might go to hospice and not PC. Overall, 277 (39%) of all patients survived less than 180 days; 156 (56%) of these had no PC referrals, and of these, only 84 (54%) were seen by hospice (Appendix 2).

Interviews with clinical team members

Of 38 clinical team members invited by e-mail, 25 (65.8%) participated in an in-person interview, 3 actively declined, and 8 never responded or were lost to follow-up. Participants included 13 medical oncology or gynecological oncology (Onc) team members: 8 physicians and 5 nurse practitioners, nurses, and social workers; and 12 PC team members: 5 physicians and 7 nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, and chaplains. Eighteen participants (72%) were female. Fourteen (56%) had been at the organization for less than 5 years. All described having discussions with patients about PC.

Clinical team members described 4 pathways for when and why referrals happen: (1) early referrals, (2) referrals without active anti-cancer treatment, (3) problem-based referrals, and (4) late referrals when disease progressed or treatment stopped (Fig. 1; Table 2). Of 9 oncology providers interviewed, 4 typically made early referrals, 3 made problem-based referrals, 1 made late referrals (when stopping treatment), and 1 almost never made referrals, instead providing holistic care and referrals to hospice: “I’m not a user of PC. I know the literature, but I’m old. I do what they [the PC providers] do.” (Onc#7).

Early referrals

Early referrals were based on the assumption that everyone with an advanced cancer should have access to concurrent PC. However, some oncologists noted that stage IV prostate or breast cancer had better long-term prognoses and would not be referred early. Early referrals happened within the first few visits:

“We know that it’s going to be an issue, eventually, so it’s always good to start them with palliative care earlier than later,” (Onc#5). These oncology providers believed early referrals reduced confusion about the distinction between PC and hospice. They also appreciated having a larger team providing concurrent care, e.g., “it takes a village.”

Referrals without anti-cancer treatment

Other early referrals were for a smaller group of patients who chose not to or were ineligible to receive active anti-cancer treatments because “they are too sick,” e.g., patients with poor functional status, dementia, or who opted out of conventional treatments.

“They don’t want to try chemo to buy a few more months, so they’re a ‘get them on board with a palliative person right away.’” (Onc#4)

Problem-based referrals

Some providers believed referrals should occur when problems arose, e.g., serious pain which the oncologist could not or did not want to manage, psycho-social needs, family support, or patients struggling to understand or accept their prognosis who were referred for “difficult coping around terminal illness.” (PC#6). Oncologists’ thresholds for wanting PC assistance varied based on their training, experience, philosophy, and willingness to let go: “A lot of time, we oncologists have a hard time letting go.” (Onc#9).

Some problem-based referrals also arose due to patients’ lack of receptivity to earlier recommendations to begin PC.

“When I introduce it [earlier in journey], I would say about half the time people are interested. They may not want it right away. They often will say, ‘Let me think about it.’ And then when they start having a little more trouble, then I’ll say, ‘Remember we talked about palliative care earlier; I wonder if now would be a time to bring them in?’ And then they might be open to it.” (Onc#2)

Late referrals

Late referrals occurred when treatments stopped working, symptoms became unbearable, or patients were ready to transition to hospice. Both oncology and PC teams found late referrals problematic: “The transition with palliative care is very short, and then they kind of dump into hospice,” (Onc#11).

“Oftentimes we see people who have more advanced symptoms that it would have been better for both the patient and our team to have sort of gotten on the ground floor of those symptoms… You know, had we been involved, her chemotherapy would have maybe been more tolerable or something like that.” (PC#10)

PC team members noted that some oncologists who were older or had less PC familiarity referred patients who were actively dying. These referrals, “sucked the energy out of palliative care” and left PC team members “distressed about it for weeks.” (PC#4)

“I’d walk in and I’d say, ‘Oh my God,’ and the patient’s actually dying, and we’re not having a palliative conversation anymore. We’re actually strangers walking in and saying, ‘I’m sorry, your mom is actually dying right now. What we should be doing is, let’s get her on hospice.’” (PC#4)

The semantics of palliative care

The language used to describe PC to patients was described as critically important because most patients know little about PC and conflate it with hospice (Table 3). Both teams stressed semantics: “I really emphasize the ‘support’ versus the ‘palliative care’ word.” (PC#2). Oncology providers noted it was easier to make pain and symptom management the talking point with patients, rather than facing a poor prognosis and dying:

“It’s an easier sell to say, ‘Okay. Your pain medication’s getting complicated. Dr. [oncologist] wants some advice from the experts and they’re in palliative care.’” (Onc#4)

PC team members described using similar phrases but added context about understanding illness, treatments, prognosis, identifying patient preferences and values, and advance care planning.

Benefits and challenges

The reported benefits of PC (Table 4) included better pain and symptom management, flexible visits (e.g., at home or during infusions), expanded teams, better advance care planning, illness understanding and prognostic awareness, end-of-life preparation, easier hospice transitions, and improved end-of-life experiences: “They talk about the power of attorney, the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), getting affairs ready with the family. I think they try to get that ball well aligned before things get worse and worse.” (Onc#1).

Barriers to referrals included patient receptivity, differences among oncologists, the time and cost to patients, “promising” new cancer treatments/research, and PC availability (Table 4). Availability concerns included wait times, lack of evening/weekend on-call, a desire for co-located teams (in clinics without it), and a limited staffing model to see patients urgently. Care team members recommended “re-branding” or “re-labelling” PC to minimize association with hospice (PC#2). Oncologists reported some patients would not try PC due to “cost and time,” or because they were too overwhelmed, “it’s sort of often in one ear out the other.” (PC#10).

Some oncologists feared that PC erodes hope, “I think palliative care can take away any hope,” (Onc#11), or “So many of these patients come and see me because they want that two percent hope.” (Onc#10). New cancer treatments and research also introduced uncertainty about when PC referral should occur: “With the new treatments, even in Stage 4, they could be around for years,” (PC#5).

Discussion

Analysis of EHR data for 1334 patients with stage IV cancer found that 705 (52.8%) died within the 6-year study period, and of these 332 (47%) were referred to PC. Among referrals, 48.5% were “early,” i.e., within 60 days after diagnosis. Median time from diagnosis to death was 4 months for patients referred early versus 14 months for later referrals. Shorter median survival for patients with early referrals suggests providers may be using poor clinical condition or anticipated poor prognosis to decide when to refer.

Patients referred to PC more frequently received hospice care than patients not referred (79% versus 55%). Median survival of 3 months after PC referral date indicates many patients were eligible for hospice care when referred to PC. Higher rates of hospice use among patients referred to PC suggest that PC facilitates hospice transitions.

Some oncologists at this organization almost never referred to PC, while others referred a majority of their patients. This research complements Le et al.’s finding that clinicians’ confidence in and beliefs about PC influence referrals [28]. The referral types described by clinicians in interviews suggest that referrals are typically based either on patients’ needs, “problem based referrals,” or time-based, based on time since diagnosis as in “early referrals,” as noted by Hui et al. [19]. Waiting to refer until problems surfaced sometimes leads to crisis or late referrals resulting in quick hospice transitions and the perception of “dumping” patients into hospice, which was problematic for oncology and PC teams and likely for patients as well.

Lack of patient receptivity to PC referral was also cited as an obstacle to early referrals in interviews. Many patients with advanced cancer do not understand that treatment is unable to cure their disease [41]. Patients’ “illness narratives” about fighting for a cure [26, 27] and the hope for new treatments and “rescue” [22] may also complicate introducing hospice and PC. Inadequate discussion of prognosis, and more time spent discussing treatment plans and logistics, dubbed the “stage IV shuffle” [3], may also compromise patients’ ability to make informed decisions.

Oncology teams endorsed many benefits of PC, but the language used to describe PC to patients required strategic messaging. Oncology and PC teams emphasized that PC was an “extra layer of support,” but the PC team added more messaging about prognostic awareness, quality of life, and advance care planning [21, 42]. Some oncology team members expressed reservations and fear that PC would erode patient hope. Challenges recounted included availability and access to PC teams, variation in oncologist referral practices, and patient misconceptions about and receptivity to PC. Given that oncologists report some patients are unwilling to consider PC at the time of diagnosis, a change in public perception and education may be a necessary first step toward expanding access to concurrent palliative care. A broader public education campaign may be necessary, as may adopting alternative language in patient interactions, such as “supportive care” rather than “palliative care” [11, 31].

These findings suggest several methods for enhancing PC referrals. Co-located oncology and PC services and relationship-building between departments may promote referrals. Eligibility algorithms [23] and EHR triggers [8, 14] may also prove beneficial as we shift toward population health strategies. However, while some evidence suggests making early PC standard care may improve patient quality of life [40], PC as a specialty may not have the capacity to meet the needs of all patients if early referrals become common [24, 30]. Additionally, new cancer treatments and research may lead to uncertainty about which cancers are incurable and pose dilemmas for clinicians determining PC eligibility.

This study was limited to one health system with a staggered roll-out of outpatient PC between 2011 and 2014. Our analysis did not control for availability of PC by site, and the interviews took place 4–7 years after local roll-out. Cross-sectional EHR data was limited to individuals with a stage IV cancer who died within a 6-year period. A majority of patients diagnosed with a stage IV cancer died within the 6-year period for which we have data; however, survival information is missing for those who survived beyond the study time period. There may be selection bias in interview participants and recall bias in interviews themselves. We explored care team descriptions of conversations, but we do not know how patients perceived those conversations.

In summary, we found high rates of referral to outpatient PC and positive assessments of PC by oncology teams; however, there was dramatic variability in timing of referrals, oncologists’ referral patterns, and beliefs about when to refer. Future research could elucidate patient and family perspectives on referral to PC and experiences with earlier and later referrals. We do not know how referral to PC for non-cancer diagnoses may differ. The interviews reveal lingering questions about variation in the timing of, and reasons for, PC referral. This exploratory study demonstrates that exclusively focusing on rates of referrals may obscure how PC referrals vary in timing, reason for referral, and usefulness to patients, families, and clinical teams.

References

Ahluwalia SC, Fried TR (2009) Physician factors associated with outpatient palliative care referral. Palliat Med 23(7):608-615

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, Dionne-Odom JN, Frost J, Dragnev KH, Hegel MT (2015) Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1438–1445

Brand DA (2019) The stage IV shuffle: elusiveness of straight talk about advanced cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 34.11(2019):2637-2642

Broom A, Kirby E, Good P, Wootton J, Adams J (2013) The art of letting go: referral to palliative care and its discontents. Soc Sci Med 78:9–16

Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center. America’s Care of Serious Illness: a state-by-state report card on access to palliative care in our nation's hospitals. 2019

Charmaz K (2017) The power of constructivist grounded theory for critical inquiry. Qual Inq 23:34–45

Compton-Phillips A, Mohta NS (2019) Care redesign survey: the power of palliative care. NEJM Catalyst

Courtright KR, Chivers C, Becker M, Regli SH, Pepper LC, Draugelis ME, O’Connor NR (2019) Electronic health record mortality prediction model for targeted palliative care among hospitalized medical patients: a pilot quasi-experimental study. J Gen Intern Med 34:1841–1847

Dans M, Smith T, Back A, Baker JN, Bauman JR, Beck AC, Block S, Campbell T, Case AA, Dalal S, Edwards H, Fitch TR, Kapo J, Kutner JS, Kvale E, Miller C, Misra S, Mitchell W, Portman DG, Spiegel D, Sutton L, Szmuilowicz E, Temel J, Tickoo R, Urba SG, Weinstein E, Zachariah F, Bergman MA, Scavone JL (2017) NCCN guidelines insights: palliative care, version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 15:989–997

de Oliveira Valentino TC, Paiva BSR, de Oliveira MA, Hui D, Paiva CE (2018) Factors associated with palliative care referral among patients with advanced cancers: a retrospective analysis of a large Brazilian cohort. Support Care Cancer 26:1933–1941

Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, Del Fabbro E, Swint K, Li Z, Poulter V, Bruera E (2009) Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name? A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 115:2013–2021

Feeg VD, Elebiary H (2005) Exploratory study on end-of-life issues: barriers to palliative care and advance directives. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 22:119–124

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Firn JI, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Phillips T (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35:96–112

Gemmell R, Yousaf N, Droney J (2019) “Triggers” for early palliative care referral in patients with cancer: a review of urgent unplanned admissions and outcomes. Support Care Cancer

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1968) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London

Greer JA, Jackson VA, Meier DE, Temel JS (2013) Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 63:349–363

Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, Lennes IT, Heist RS, Gallagher ER, Temel JS (2012) Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:394–400

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18:59–82

Hui D, Anderson L, Tang M, Park M, Liu D, Bruera E (2020) Examination of referral criteria for outpatient palliative care among patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 28:295–301

Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, Dev R, Chisholm G, Bruera E (2014) Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 120:1743–1749

Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Temel JS, Back AL (2013) The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med 16:894–900

Jacobson JO (2019) Managing cancer patients' expectations amid hope and hype. Health Aff (Millwood) 38:320–323

Jung K, Sudat SE, Kwon N, Stewart WF, Shah NH (2019) Predicting need for advanced illness or palliative care in a primary care population using electronic health record data. J Biomed Inform:103115

Kamal AH, Wolf SP, Troy J, Leff V, Dahlin C, Rotella JD, Handzo G, Rodgers PE, Myers ER (2019) Policy changes key to promoting sustainability and growth of the specialty palliative care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 38:910–918

Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, Dev S, Biddle AK, Reeve BB, Abernethy AP, Weinberger M (2014) “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. Am Heart J 3:e000544

Kirby ER, Kenny KE, Broom AF, Oliffe JL, Lewis S, Wyld DK, Yates PM, Parker RB, Lwin Z (2020) Responses to a cancer diagnosis: a qualitative patient-centred interview study. Support Care Cancer 28:229–238

Kleinman A (1988) The illness narratives: suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books, New York

Le BH, Mileshkin L, Doan K, Saward D, Spruyt O, Yoong J, Gunawardana D, Conron M, Philip J (2014) Acceptability of early integration of palliative care in patients with incurable lung cancer. J Palliat Med 17:553–558

LeBlanc T, Nickolich M, El-Jawahri A, Temel J (2015) Discussing the evidence for upstream palliative care in improving outcomes in advanced cancer. In: Editor (ed)^(eds) Book discussing the evidence for upstream palliative care in improving outcomes in advanced cancer, City, pp. e534-538

Lupu D, American Academy of H, Palliative Medicine Workforce Task F (2010) Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manag 40:899–911

Maciasz R, Arnold R, Chu E, Park S, White D, Vater L, Schenker Y (2013) Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Support Care Cancer 21:3411–3419

Meier D, Beresford L (2008) Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med 11:823–828

Muir JC, Daly F, Davis MS, Weinberg R, Heintz JS, Paivanas TA, Beveridge R (2010) Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manag 40:126–135

O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 89:1245–1251

Rabow M, Kvale E, Barbour L, Cassel JB, Cohen S, Jackson V, Luhrs C, Nguyen V, Rinaldi S, Stevens D (2013) Moving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med 16:1540–1549

Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Ferrell BR, Loscalzo M, Meier DE, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Somerfield M, Stovall E, Roenn JHV (2012) American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 30:880–887

Sullivan DR, Chan B, Lapidus JA, Ganzini L, Hansen L, Carney PA, Fromme EK, Marino M, Golden SE, Vranas KC (2019) Association of early palliative care use with survival and place of death among patients with advanced lung cancer receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Oncol

Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, Pirl WF, Park ER, Jackson VA, Back AL, Kamdar M, Jacobsen J, Chittenden EH, Rinaldi SP, Gallagher ER, Eusebio JR, Li Z, Muzikansky A, Ryan DP (2017) Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and gi cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35:834–841

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742

Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, Surmont V, De Laat M, Colman R, Eecloo K, Cocquyt V, Geboes K, Deliens L (2018) Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 19:394–404

Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, Finkelman MD, Mack JW, Keating NL, Schrag D (2012) Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 367:1616–1625

Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, Jackson VA, Gallagher ER, Pirl WF, Back AL, Temel JS (2013) Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 173:283–290

Yu JA, Ray KN, Park SY, Barry A, Smith CB, Ellis PG, Schenker Y (2018) System-level factors associated with use of outpatient specialty palliative care among patients with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract 15:e10–e19

Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I (2014) Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383:1721–1730

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank Pragati Kenkare, Mai Vu, and Lydia Jacobs for their support accessing data required for this analysis. We thank Yan Yang and Qiwen Huang for data analysis support. We thank members of the Palo Alto Medical Foundation medical oncology and palliative care teams for their help and participation in these interviews.

Authors’ contribution statements

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Ellis Dillon, Jinnan Li, Amy Meehan, and Nina Szwerinski. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ellis Dillon, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data and/or code availability

The authors do not have permission to share the electronic health record dataset or interview transcript dataset. Requests to see further data can be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Philanthropy Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The Sutter Health Institutional Review Board approved this research study including the retrospective analysis of Electronic Health Record data and the in-depth interviews with clinical care team members.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dillon, E.C., Meehan, A., Li, J. et al. How, when, and why individuals with stage IV cancer seen in an outpatient setting are referred to palliative care: a mixed methods study. Support Care Cancer 29, 669–678 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05492-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05492-z