Abstract

Purpose

The existence of cancer disparities is well known. Focus on alleviating such disparities centers on diagnosis, treatment, and mortality. This review surveyed current knowledge of health disparities that exist in the acute survivorship period (immediately following diagnosis and treatment) and their contributors, particularly for African-American breast cancer survivors (AA-BCS).

Methods

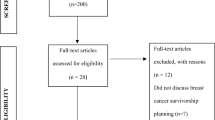

Utilizing the ASCO four components of survivorship care, we explore disparities in surveillance and effects of cancer and therapies that AA-BCS face within the acute survivorship period (the years immediately following diagnosis). A literature review of PUBMED, Scopus, and Cochrane databases was conducted to identify articles related to AA-BCS acute survivorship. The search yielded 97 articles. Of the 97 articles, 38 articles met inclusion criteria.

Results

AA-BCS experience disparate survivorship care, which negatively impacts quality of life and health outcomes. Challenges exist in surveillance, interventions for late effects (e.g., quality-of-life outcomes, cardiotoxicity, and cognitive changes), preventing recurrence with promotion of healthy living, and coordinating care among the healthcare team.

Conclusions

This overview identified current knowledge on the challenges in survivorship among AA-BCS. Barriers to optimal survivorship care inhibit progress in eliminating breast cancer disparities. Research addressing best practices for survivorship care is needed for this population. Implementation of culturally tailored care may reduce breast cancer disparities among AA-BCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is limited research on survivorship care that is tailored to minorities, specifically African-American (AA) breast cancer survivors (BCS), despite the fact that breast cancer disparities, including higher cancer-related mortality and poorer quality of life, are frequently seen in AA women [1,2,3,4,5]. Moreover, the incidence of breast cancer among AA women is rising and converging with rates among White women [3]. However, there is little research among AA-BCS populations during the acute survivorship, or the period immediately following diagnosis and treatment [6].

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and ASCO have outlined four critical components to optimal survivorship care: 1) Surveillance for the spread of cancer, recurrence, or secondary cancers; 2) Interventions for late effects of cancer and treatment (e.g., other medical problems or quality-of-life changes); 3) Prevention to reduce recurrence and development of new cancers; 4) Coordination among specialists and primary care providers to ensure that all the survivors’ needs are met [7]. Disparities exist within each component and the causation of disparities in survivorship is complex and multivariate, ranging from several factors that cut across the breast cancer care continuum: stage at diagnosis, comorbidities, access to care [3, 8, 9]. The purpose of this study is to present health disparities that exist in the acute survivorship period for AA-BCS and their contributors, based on the current IOM guidelines for adequate survivorship care [7].

Methods

A literature review was performed to present health disparities within the four components of survivorship care among African-American breast cancer survivors based on current IOM guidelines. This overview includes English-language articles published in peer-reviewed journals from January 2008 to June 2018. Articles were retrieved from three multidisciplinary academic databases: Pubmed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Cochrane review. Keywords and MESH search terms were as follows: “breast cancer,” “survivorship,” “disparities,” OR “African-American.” The search yielded 82 PubMed, 12 SCOPUS, and 3 Cochrane references—a total of 97 articles. Each of the articles were reviewed based on inclusion criteria: sampled African-American breast cancer survivors within at least 10 years of diagnosis, discussed medically relevant survivorship issues, and had statistically significant data. There were no limitations based on sample size; data from articles with a sample size less than 20% AA-BCS are presented with an acknowledgement of the number of AA-BCS. Fifty-nine of the reviewed articles were discarded (33 did not specifically discuss acute survivorship disparities, 17 did not specifically discuss evaluating race, 5 did not specifically address AA-BCS or presented aggregated data, 1 had statistically insignificant data). Thirty-eight articles remained and were included in this review. Data were abstracted and analyzed, grouping findings based on the four survivorship components (see Table 1 for more full article list). The following section details the state of acute survivorship care among African-Americans as addressed in this literature.

Results

Surveillance

Surveillance for secondary cancers is an important part of care given during the acute survivorship period. Given the increased risk of mortality and recurrence, survivors require routine follow-up care based on standard breast care guidelines (seen every 3–6 months in the first 5 years) [10]. Imaging with mammography is routine follow-up care for women who do not undergo mastectomy to remove all breast tissue. AA-BCS are more likely to withdraw from breast cancer survivorship care and treatment (mammography adherence OR = 1.35, 95% CI; clinic visits OR = 1.62, 95% CI) than White BCS [11]. Further, Nurgalieva et al. found that lower surveillance rates among AA women was also linked to higher mortality within 2 years of diagnosis [12].

Considering rationales for disparity in follow-up care, many AA-BCS report that the medical cost of health care during surveillance is a major barrier to accessing survivorship care [13]. In a survey of diverse survivors, Palmer et al. found that AA women were more likely to report out of pocket expenses as a major barrier (51.6%) than White women (28%), which was similar to other health care costs (45.2% in AA and 21.3% in white women, P = 0.01) [14]. Such costs include transportation, prescription medication, and dental care expenses. The direct effect of the high cost of health care increases the likelihood of AA women forgoing medical care and/or following-up with providers [15].

Interventions for late effects

In addition to surveillance, follow-ups are important to screen for late effects from cancer treatment that may require intervention. Late effects discussed within the selected articles that include quality-of-life changes, lymphedema, sexuality concerns, cardiotoxicity, neuropathy, and cognitive changes. Late effects can lead to functional disability, which was noted to be more prevalent among older African-American breast cancer survivors compared to their White counterparts [16].

Quality-of-life outcomes

Russell et al. noted the importance of recognizing the more immediate quality of life, or well-being, concerns that exist in acute survivorship as well as long-term [17]. Another article discussed quality of life in survivors that were at least 1 year out from treatment [18]. Health-related quality of life in these breast cancer patients was dependent on the presence or absence of certain comorbidities. AA women were shown to have many other chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension and arthritis) that negatively impacted their overall quality of life [18].

Lymphedema

A major issue faced by breast cancer patients after surgery is lymphedema, or swelling of extremities due to reduced lymphatic drainage. Beaulac et al. found that lymphedema rates were similar in women undergoing mastectomy and conservative surgery [19]. When evaluating quality of life, women who experience lymphedema report relatively lower quality of life on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) than those who do not experience lymphedema [19]. It is also well established that AA-BCS experience greater upper extremity disability as a result of lymphedema and lack of follow-up care which increases survivorship disparities in AA women [20].

Sexuality concerns

Barsevick et al. found that AA-BCS reported sexuality concerns and educational resources compared to a mixed group of breast cancer survivors. Sexual concerns were greater in younger and unmarried women [21]. In a qualitative study, AA-BCS less than 45 years old reported difficulty with sexual intercourse, sexual dysfunction, and decreased sexual desire [22]. Lewis et al. also found that young AA-BCS were less inclined to discuss sexual side effects with their health care providers. Additional concerns that were impacted by sexuality were fertility preservation and reconstructive surgery [22].

Fertility preservation

Studies have shown that younger women can suffer from distress related to infertility issues [23]; yet, over 20% of AA-BCS reported not receiving fertility information [23,24,25]. Another study found that nearly half of the AA-BCS in their cohort had no fertility discussions with their oncologists about treatment-related risks to fertility [26]. As a possible solution, Schover et al. suggests the benefit of the SPIRIT intervention for AA-BCS [27]. The SPIRIT intervention was designed to improve knowledge and reduce symptoms related to sexual dysfunction, menopause, and distress about infertility in AA-BCS. The study showed reproductive health knowledge increased, and the women’s emotional distress related to sexual dysfunction, and loss of fertility decreased [27].

Impact of reconstructive surgery

Reconstructive surgery can also impact sexuality concerns as women come to terms with their new bodies. Alderman et al. evaluated the use of reconstructive surgery or information regarding the procedure around the time of diagnosis in different racial/ethnic groups [28]. Results showed significant variation in the receipt of reconstructive surgery based on race/ethnicity with a 40.9% rate in White women as opposed to 33.5% rates in AA women. Women from minority groups were less likely to see a surgeon before surgery and minority women without reconstructive surgery had low surgical decision-making satisfaction rates when compared to white women (P < 0.001) [28]. It was shown that these women had less counseling from their surgeon in regard to reconstructive surgery options [28].

Cardiotoxicity

Anthracycline-based therapies, like doxorubicin, have well-documented cardiotoxicity effects, such as dilated cardiomyopathy [29, 30]. A retrospective study noted a nearly threefold increase in the rate of cardiotoxicity among their AA breast cancer patients compared to their non-White counterparts [31]. Grenier and Lipshultz performed a review of childhood cancers and found that AA survivors were at an increased risk of early cardiotoxicity [32]. It is unclear if the same is true in adult AA cancer survivors. The etiology of this disparity is unclear, but may be partially due to genetics and complicated by other medical comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes [32]. Additional research in this area is needed.

Neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy is a major taxane-based chemotherapy side effect [33, 34]. AA-BCS had a higher prevalence of taxane-induced neuropathy compared to non-AA-BCS (53% vs. 22%) [35]. Further, Schneider et al. found that AA-BCS are at increased risk of developing both moderate and severe neuropathy secondary to taxane-based chemotherapy [36]. In further analyses, they find a genetic variation (polymorphism) in the Charcot-Marie-Tooth gene (SBF2), which can predict an increased risk of taxane-induced neuropathy in AA breast cancer patients [36]. Other polymorphisms have been associated with an increased risk of therapy-associated neuropathy but not associated with race [33, 34]. As with cardiotoxicity, additional research is needed to better understand clinical and genetic risk factors for this very common treatment-related complication [35,36,37,38].

Cognitive changes

Cognitive side effects from chemotherapy, also known as “chemobrain,” have been reported among breast cancer survivors [39]. It is characterized by a range of symptoms, including memory loss, difficulty thinking, and inability to concentrate and multitask. This has been shown to impact quality of life [39]. However, further research is still needed on how this “chemobrain” may differently affect minority populations. One study performed focus groups among underserved AA-BCS [40]. One of the main issues the women expressed was not knowing about the existence of “chemobrain” as their healthcare professional never mentioned it prior to treatment [40]. As discussed later, provider-patient communication in survivorship is an area that needs further improvement for AA-BCS.

Prevention

Prevention is a key component of survivorship care. Unlike surveillance, prevention and detection of new cancers and recurrent cancer underscore care measures taken to decrease the risk of developing cancer recurrence and/or lasting late effects. The selected articles detail prevention among AA-BCS focused on physical activity and diet for recurrence risk reduction.

Physical activity

AA women are at higher risk of increased rates of obesity and lack of physical activity, which negatively affects overall breast cancer survivorship and quality of life [41, 42]. A study by Hair et al. examined the different determinants of activity levels of women with breast cancer before and after diagnosis [43]. Participants reported a decrease of about 59% in physical activity after diagnosis; AA women when compared to White women were less likely to meet their physical activity target (OR, 1.38; 95% CI) [43]. The study concluded that post-treatment interventions need to be directed towards encouraging physical activity in order to reduce breast cancer survivorship disparities in AA women [43].

Diet

Diet is also an important factor in determining breast cancer survivorship outcomes. Lower survival rate seen in AA-BCS is partly attributed to obesity and high fat diets [44]. Royak-Schaler et al.’s study examined behavioral modifications, such as diet and physical therapy [44]. Patients report not being informed by their providers on a recommended diet or level of physical activity [34]. Though the rates of obesity are very high in AA women, weight reduction programs targeting breast cancer survivors in AA communities are few [44]. Stolley et al. evaluated the feasibility of a weight loss program in AA-BCS known as Moving Forward and noted significant weight improvements after a six-month period as a result of diet, physical exercise, and social support [45]. Results showed that physical activity, healthy diet with more vegetables, and less fat intake improved quality of life of the participants [45]. Paxton et al. noted that AA-BCS were interested in culturally sensitive interventions on physical activity, but are underrepresented in clinical trials promoting positive health behaviors [46].

Coordination between specialists and primary care providers

Appropriate patient follow-up requires coordination between oncology specialists and primary care providers. When AA-BCS complete treatment, they are faced with the complex challenge of transitioning out of treatment and into primary care, seeking to gain the support and resources needed for managing life as a survivor [47]. The selected articles detail patient-provider communication, survivorship care plans, and systemic factors to delivery of survivorship care.

Patient-provider communication

Articles in this review identified patient-provider communication as a potential barrier to care coordination. In considering ways to strengthen communication, patient engagement in their own care can be improved by paying attention to non-verbal cues and by requesting the patient’s perspective into how their disease process and treatment are coming along [48]. Maly et al. evaluated factors that affect preventive care and breast cancer survivorship outcome 3 years after breast cancer diagnosis in low-income women (4.3% of whom were African-American) [49]. They found that women who visited their primary care providers in addition to their oncology specialists or surgeons had better outcomes than those who only visited their oncologist, indicating that low-income populations require timely follow-up care after breast cancer diagnosis [49]. It is still unclear as to who is the best provider to coordinate this communication between the patient and provider and between providers in the follow-up period [47]. It is recommended that the oncologists send communications and updates in plan, including surveillance, to the primary care provider [47].

Cultural competency

Cultural competence requires the demonstration of awareness of cultural norms and beliefs, knowledge of how culture may differ across groups, being sensitive to culture, and ultimately making adjustments to accommodate culture [50]. This review identified culturally competent interventions for this group including significant others in patient conversations and address spirituality and faith [51,52,53,54,55]. A focus group of AA-BCS noted the importance of culturally competent care, where practitioners (primary care and oncologists) understand these women’s past experiences and family histories, as these contribute to the survivors’ psychosocial standing [51]. White-Means et al. found factors that negatively impacted their survivorship which were inadequate provider care in the treatment of pain, lack of needed support from friends and family, and disability limitations that can be mental or physical [52]. A study by Kantsiper et al. found that spirituality and personal growth were important issues for these AA women, especially since there is still a social taboo about breast cancer in AA communities [53]. A unique study provided their participants with personal cameras that were used to record their daily activities during their breast cancer survivorship experience [55]. Careful analysis of their recorded survivorship experience showed that the quality of life was highly dependent on three social factors, which included racism, cancer stigmatization, and what the culture aspects of AA women [55].

In addition, African-Americans have reported a distrust of the health care system because of past discriminatory practices; for example, some women reported continued fear and suspicion from the Tuskegee airmen case by the US Public Health Service [53].

Utilization of survivorship care plans (SCPs)

Regarding more comprehensive follow-up care, a cancer survivorship care plan (SCP) was suggested as an intervention to improve follow-up care, per the Institute of Medicine. One of the first studies dealing with follow-up information presented to AA-BCS showed that that there were significant gaps in guidelines for surveillance, symptoms after treatment, and prevention [7]. The study points out the importance of addressing the diverse needs of survivors, particularly AA in this setting, in order to develop practical and feasible care plans. Kvale et al. found that the transition to survivorship care is an individualized process and that a survivor’s response to behavioral change is dependent on their personal and past experiences [56, 57].

Ashing-Giwa et al. focused on formatting the SCP to the AA-BCS to ensure more efficacy [58]. Ashing-Giwa et al. and Burg et al. found that survivors themselves preferred the information to be presented in a way that was particularly relevant for AA-BCS [58, 59]. This included a cover page outlining follow-up providers who are more culturally competent towards AA, and healthy lifestyle practices. They also comment on the importance of spirituality and quality of life for these survivors, and that reflection in the SCPs. Psychosocial support was again emphasized by Burg et al. through focus group discussions [58].

Patient navigators

Another strategy suggested is the use of patient navigators. A study by Mollica et al. examined the use of peer navigators exclusively in the AA population who were also breast cancer survivors. The qualitative results showed that the breast cancer survivors felt support from the peer navigators as they “shared a common journey” [60]. Survivors and navigators also reported that home visits were beneficial. The study does point out the limitations of peer navigation, as there were issues with navigator recruitment and finding the right person for the role, along with commitment to follow-up and prior work commitments. The use of patient navigators, who are breast cancer survivors themselves, has been shown to improve patient outcomes in terms of coping with the disease and assisted with adherence to follow-up care [61, 62]. Davis et al. also found that peer navigators could help provide emotional support as needed for AA-BCS [61]. Not only were these navigators available for the patient, but they also provided coping strategies for the family members. They showed that navigators can be used across the continuum of cancer care [61].

Many studies are patient-focused and address issues such as patient education and training. However, Daly and Olopade discuss how very few studies address changing the healthcare system and delivery [2]. They suggest that a focus on combining insurance coverage, patient education/communication, and patient navigation in interventions can be further researched to assess its effectiveness in breast cancer approaches. Furthermore, the concept of a medical home, a centralized location/physician where patient care is coordinated, has been shown to reduce ethnic and racial disparities in general health care, not just cancer [63].

Discussion

Breast cancer survivorship can be a complicated journey for some survivors, particularly if there are long-term side effects of treatment and challenges with health maintenance and health promotion. This review summarizes how survivorship care management can be challenging for AA-BCS. These women bear a larger burden of disease, including more advanced disease at diagnosis and greater potential for comorbidities, than White women. The acute survivorship period is particularly important as many AA-BCS need culturally competent care to address coping needs and strategize follow-up care. Unfortunately, survivorship care among AA-BCS is understudied. There is paucity in our understanding of how AA-BCS perceive their lives after breast cancer [42, 62, 64]. This review places greater perspective on how AA-BCS experience survivorship and how their particular social and racial context shapes their experience of survivorship and survivorship care.

Given the converging breast cancer incidence rates between AA and White women, surveillance and preventative practices are paramount in this already at-risk population of women [3]. Timely detection and management of disease increase likelihood of achieving remission. It is clear that current survivorship guidelines recommend surveillance and preventative practices [10]; however, our review indicates that there are barriers in meeting these guidelines and reciprocal issues with compliance.

Culturally competent post-treatment interventions may increase the likelihood of AA-BCS meeting survivorship guidelines [10]; unfortunately, such interventions are lacking for AA-BCS. This review identified that cultural competency among AA-BCS involves the use of spirituality and social support to cope with their disease and treatment. Recognition that culture even among those that consider themselves as AA may be different is key. Therefore, personalizing the approach to each patient may yield better intervention effects and highlights the importance of individual assessment of supportive care needs [10].

Further, this review demonstrates that there is a lack of integration of care across the breast cancer care continuum. Often there is confusion about who should deliver survivorship care across the continuum, as well as how health information in the form of SCPs is communicated in a culturally competent manner. Another suggested approach by Daly and Olopade is the concept of an oncology medical home [2]. Elaborating on the concept of an accountable care organization, this concept has shown success by focusing on long-term coordinated care where reimbursement is based on performance and outcomes, and not traditional fee-for-service models.

Review findings indicate areas for future research including identifying the best ways to ensure quality survivorship care for AA-BCS, seeking to eliminate survivorship disparities. The presented literature supports the use of system-wide approaches to reduce racial disparities, such as the idea of a medical oncology home [2]. Another strategy is the Public Health Action Model for Cancer Survivorship [65]. This model uses a social ecological framework (i.e., individual, community, organization, and policy) within the National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship to enhance public health collaborations and provide more effective survivorship care [65]. Within such systems, a large concern is determining who is the most appropriate person to deliver survivorship care plans [44], and if patient navigators are used to improve care coordination, who should be recruited as patient navigators [60]. More importantly, research is needed to understand how to best apply cultural competence across survivorship interventions. As we strive towards these healthy initiatives, evidence-based care may help reduce breast cancer disparities.

There were limitations to this overview. Though we used an organized approach to literature review, we did not perform an expansive systematic review. Therefore, our search may have missed relevant articles that would deepen understanding of the reviewed topic. We also acknowledge that some articles included in the review had small samples of AA-BCS. Given the limited articles describing acute survivorship for AA-BCS, we included such articles to give more perspective. This literature review provides an overview to generate discussion and promote future research in this area.

Conclusion

This overview identified what is known about challenges of survivorship and survivorship care among AA-BCS. Understanding of this phenomenon centers on how AA-BCS approach surveillance, provision of interventions for addressing late effects, promotion of healthy living strategies, and coordinating care throughout the care continuum. Barriers to optimum survivorship care inherently inhibit progress in eliminating breast cancer disparities. Research on best practices to deliver survivorship care in this population is needed. Implementation of culturally tailored care may reduce breast cancer disparities among AA-BCS.

References

McCarthy AM, Yang J, Armstrong K (2015) Increasing disparities in breast cancer mortality from 1979 to 2010 for US black women aged 20 to 49 years. Am J Public Health 105(Suppl 3):S446–S448

Daly B, Olopade OI (2015) A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin 65:221–238

DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A (2016) Breast cancer statistics, 2015: Convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin 66:31–42

Tammemagi CM, Nerenz D, Neslund-Dudas C, Feldkamp C, Nathanson D (2005) Comorbidity and survival disparities among black and white patients with breast cancer. JAMA 294:1765–1772

Polite BN, Cirrincione C, Fleming GF, Berry DA, Seidman A, Muss H, Norton L, Shapiro C, Bakri K, Marcom K, Lake D, Schwartz JH, Hudis C, Winer EP (2008) Racial Differences in Clinical Outcomes from Metatstatic Breast Cancer: a pooled analysis of CALGB 9342 and 9840—Cancer and Leukemia Group. B. J Clin Oncol 26:2659–2665

Mullan F (1985) Seasons of survival: reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med 313:270–273

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving care and quality of life. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Access 15 April 2013

Kim SH, Ferrante J, Won BR, Hameed M (2008) Barriers to adequate follow-up during adjuvant therapy may be important factors in the worse outcome for Black women after breast cancer treatment. World J Surg Oncol 6:26

Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Mayer DK (2015) Health disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Semin Oncol Nurs 31:170–177

Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL, Cannady RS, Pratt-Chapman ML, Edge SB, Jacobs LA, Hurria A, Marks LB, LaMonte SJ, Warner E, Lyman GH, Ganz PA (2016) American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol 34:611–635

Advani PS, Ying J, Theriault R, Melhem-Bertrand A, Moulder S, Bedrosian I, Tereffe W, Black S, Pini TM, Brewster AM (2014) Ethnic disparities in adherence to breast cancer survivorship surveillance care. Cancer 120:894–900

Nurgalieva ZZ, Franzini L, Morgan R, Vernon SW, Liu CC, Du XL (2013) Surveillance mammography use after treatment of primary breast cancer and racial disparities in survival. Med Oncol 30:691

Thompson HS, Littles M, Jacob S, Coker C (2006) Posttreatment breast cancer surveillance and follow-up care experiences of breast cancer survivors of African descent: an exploratory qualitative study. Cancer Nurs 29:478–487

Palmer NR, Weaver KE, Hauser SP, Lawrence JA, Talton J, Case LD, Geiger AM (2015) Disparities in barriers to follow-up care between African American and White breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 23:3201–3209

Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM (2010) Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer 116:3493–3504

Owusu C, Schluchter M, Koroukian SM, Mazhuvanchery S, Berger NA (2013) Racial disparities in functional disability among older women with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer 119:3839–3846

Russell KM, Von Ah DM, Giesler RB, Storniolo AM, Haase JE (2008) Quality of life of African American breast cancer survivors: how much do we know? Cancer Nurs 31:E36–E45

Ashing K, Rosales M, Lai L, Hurria A (2014) Occurrence of comorbidities among African-American and Latina breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 8:312–318

Beaulac SM, McNair LA, Scott TE, LaMorte WW, Kavanah MT (2002) Lymphedema and quality of life in survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Arch Surg 137:1253–1257

Dean LT, DeMichele A, LeBlanc M, Stephens-Shields A, Li SQ, Colameco C, Coursey M, Mao JJ (2015) Black breast cancer survivors experience greater upper extremity disability. Breast Cancer Res Treat 154:117–125

Barsevick AM, Leader A, Bradley PK, Avery T, Dean LT, DiCarlo M, Hegarty SE (2016) Post-treatment problems of African American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24:4979–4986

Lewis PE, Sheng M, Rhodes MM, Jackson KE, Schover LR (2012) Psychosocial concerns of young African American breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 30:168–184

Salsman JM, Yanez B, Smith KN, Beaumont JL, Snyder MA, Barnes K, Clayman ML (2016) Documentation of Fertility Preservation Discussions for Young Adults with Cancer: examining compliance with treatment guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 14:301–309

Peate M, Meiser B, Hickey M, Friedlander M (2009) The fertility-related concerns, needs and preferences of younger women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 116:215–223

Schover LR, Rhodes MM, Baum G, Adams JH, Jenkins R, Lewis P, Jackson KE (2011) Sisters Peer Counseling in Reproductive Issues After Treatment (SPIRIT): a peer counseling program to improve reproductive health among African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer 117:4983–4992

Vadaparampil ST, Christie J, Quinn GP, Fleming P, Stowe C, Bower B, Pal T (2012) A pilot study to examine patient awareness and provider discussion of the impact of cancer treatment on fertility in a registry-based sample of African American women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 20:2559–2564

Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE (2006) Randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 24:1620–1626

Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Morrow M, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, Katz SJ (2009) Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of postmastectomy breast reconstruction: results from a population- based study. J Clin Oncol 27:5325–5330

Lefrak EA, Pitha J, Rosenheim S, Gottleib JA (1973) A clinicopathologic analysis of adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Cancer 32:302–314

Singal PK, Li T, Kumar D, Danelisen I, Iliskovic N (2000) Adriamycin-induced heart failure: mechanism and modulation. Mol Cell Biochem. 207:77–86

Hasan S, Dinh K, Lombardo F, Kark J (2004) Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc 96:196–199

Grenier MA, Lipshultz SE (1998) Epidemiology of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in children and adults. Semin Oncol 25:72–85

Argyriou AA, Koltzenburg M, Polychronopoulos P, Papapetropoulos S, Kalofonos HP (2008) Peripheral nerve damage associated with administration of taxanes in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 66:218–228

Hershman DL, Weimer LH, Wang A et al (2011) Association between patient reported outcomes and quantitative sensory tests for measuring longterm neurotoxicity in breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant paclitaxel chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 125:767–774

Bhatnagar B, Gilmore S, Goloubeva O, Pelser C, Medeiros M, Chumsri S, Tkaczuk K, Edelman M, Bao T (2014) Chemotherapy dose reduction due to chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant settings: a single-center experience. Springerplus 3:366

Schneider BP, Lai D, Shen F, Jiang G, Radovich M, Li L, Gardner L, Miller KD, O'Neill A, Sparano JA, Xue G, Foroud T, Sledge GW (2016) Charcot-Marie-Tooth gene, SBF2, associated with taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy in African Americans. Oncotarget 7:82244–82253

Hertz DL, Roy S, Motsinger-Reif AA, Drobish A, Clark LS, McLeod HL, Carey LA, Dees EC (2013) CYP2C8*3 increases risk of neuropathy in breast cancer patients treated with paclitaxel. Ann Oncol 24:1472–1478

Baldwin RM, Owzar K, Zembutsu H, Chhibber A, Kubo M, Jiang C, Watson D, Eclov RJ, Mefford J, McLeod HL, Friedman PN, Hudis CA, Winer EP, Jorgenson EM, Witte JS, Shulman LN, Nakamura Y, Ratain MJ, Kroetz DL (2012) A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for paclitaxel-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy in CALGB 40101. Clin Cancer Res 18:5099–5109

Boykoff N, Moieni M, Subramanian SK (2009) Confronting chemobrain: an in-depth look at survivors' reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J Cancer Surviv 3:223–232

Rust C, Davis C (2013) Chemobrain in underserved African American breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Clin J Oncol Nurs 17:E29–E34

Coughlin SS, Yoo W, Whitehead MS, Smith SA (2015) Advancing breast cancer survivorship among African-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 153:253–261

Paxton RJ, Taylor WC, Chang S, Courneya KS, Jones LA (2013) Lifestyle behaviors of African American breast cancer survivors: a Sisters Network, Inc. study. PLoS One 8:e61854

Hair BY, Hayes S, Tse CK, Bell MB, Olshan AF (2014) Racial differences in physical activity among breast cancer survivors: implications for breast cancer care. Cancer 120:2174–2182

Royak-Schaler R, Passmore SR, Gadalla S, Hoy MK, Zhan M, Tkaczuk K, Harper LM, Nicholson PD, Hutchison AP (2008) Exploring patient-physician communication in breast cancer care for African American women following primary treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum 35:836–843

Stolley MR, Sharp LK, Oh A, Schiffer L (2009) A weight loss intervention for African American breast cancer survivors, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis 6:A22

Paxton RJ, Nayak P, Taylor WC, Chang S, Courneya KS, Schover L, Hodges K, Jones LA (2014) African-American breast cancer survivors' preferences for various types of physical activity interventions: a Sisters Network Inc. web-based survey. J Cancer Surviv 8:31–38

Ganz PA (2009) Survivorship: adult cancer survivors. Prim Care 36:721–741

Palmer NR, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Aziz NM, Blanch-Hartigan D, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Weaver KE (2014) Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 32:4087–4094

Maly RC, Liu Y, Diamant AL, Thind A (2013) The impact of primary care physicians on follow-up care of underserved breast cancer survivors. J Am Board Fam Med 26:628–636

Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JR, Ananeh-Firempong O II (2003) Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health carePreview the document. Public Health Reports 118:293–302

Kooken WC, Haase JE, Russell KM (2007) "I've been through something": poetic explorations of African American women's cancer survivorship. West J Nurs Res 29:896–919 discussion 920-899

White-Means S, Rice M, Dapremont J, Davis B, Martin J (2015) African American Women: Surviving Breast Cancer Mortality against the Highest Odds. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:ijerph13010006

Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC (2009) Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med 24(Suppl 2):S459–S466

Yoo GJ, Levine EG, Pasick R (2014) Breast cancer and coping among women of color: a systematic review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 22:811–824

Lopez ED, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N (2005) Quality-of-life concerns of African American breast cancer survivors within rural North Carolina: blending the techniques of photovoice and grounded theory. Qual Health Res 15:99–115

Kvale EA, Meneses K, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bakitas M, Ritchie C (2015) Formative research in the development of a care transition intervention in breast cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19:329–335

Smith SL, Singh-Carlson S, Downie L, Payeur N, Wai ES (2011) Survivors of breast cancer: patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. J Cancer Surviv 5:337–344

Ashing-Giwa K, Tapp C, Brown S, Fulcher G, Smith J, Mitchell E, Santifer RH, McDowell K, Martin V, Betts-Turner B, Carter D, Rosales M, Jackson PA (2013) Are survivorship care plans responsive to African-American breast cancer survivors?: voices of survivors and advocates. J Cancer Surviv 7:283–291

Burg MA, Lopez ED, Dailey A, Keller ME, Prendergast B (2009) The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med 24(Suppl 2):S467–S471

Mollica MA, Nemeth LS, Newman SD, Mueller M, Sterba K (2014) Peer navigation in African American breast cancer survivors. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 5:131–144

Davis C, Darby K, Likes W, Bell J (2009) Social workers as patient navigators for breast cancer survivors: what do African-American medically underserved women think of this idea? Soc Work Health Care 48:561–578

Mollica M, Nemeth L (2015) Transition from patient to survivor in African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 38:16–22

Beal AC, Doty MM, Hernandez SE, Shea KK, Davis K (2007) Closing the Divide: How Medical Homes Promote Equity in Health Care—Results from the Commonwealth Fund 2006 Health Care Quality Survey. The Commonwealth Fund, New York, NY

Nolan TS, Frank J, Gisiger-Camata S, Meneses K (2018) An Integrative Review of Psychosocial Concerns Among Young African American Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs 41:139–155

Moore AR, Buchanan ND, Fairley TL, Lee Smith J (2015) Public Health Action Model for Cancer Survivorship. Am J Prev Med 49:S470–S476

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no financial disclosures. There are no companies that have sponsored this research. The authors have full control of all primary data, and we agree to allow the journal to review any data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Husain, M., Nolan, T.S., Foy, K. et al. An overview of the unique challenges facing African-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 27, 729–743 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4545-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4545-y