Abstract

Purpose of study

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by sudden onset, intensive treatment, a poor prognosis, and significant relapse risk. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being among AML survivors have been extensively studied during the 6 months of active treatment. However, it is not clear what survivors experience after active treatment. The purpose of our study was to explore how AML survivors describe their longer-term physical and psychosocial well-being and how they cope with these challenges.

Methods

We conducted a prospective qualitative study and interviewed 19 adult participants (11 had completed treatment, 8 were receiving maintenance chemotherapy). Data were collected using semi-structured interviews that were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The grounded theory approach was used for data analysis.

Results

A marked improvement in physical health was reported; however, psychosocial well-being was compromised by enduring emotional distress. A range of emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies were reported. Keeping one’s mind off negative things through engaging in formal work or informal activities and seeking control were the two most commonly used coping strategies. Seeking social support for reassurance was also common. Problem-focused strategies were frequently described by the ongoing treatment group to manage treatment side effects.

Conclusion

Although physical symptoms improved after completion of treatment, psychosocial distress persisted over longer period of time. In addition, essential needs of AML survivors shifted across survivorship as psychological burden gradually displaced physical concerns. The integral role of coping mechanisms in the adaptation process suggests a need for effective and ongoing psychological interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

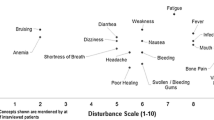

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an aggressive hematological malignancy characterized by abrupt onset, intensive treatment regimen, a relatively poor prognosis, and significant risk of relapse [1]. Immediate and intensive treatment which requires prolonged hospitalization is crucial to prevent premature death [2]. Although various treatments exist, intensive chemotherapy (IC) is the treatment of choice to achieve disease remission and prolong survival [1, 3]. However, IC is burdened with severe toxicities and distress [4–6]. In our recent study in patients with AML, we showed that fatigue, weakness, dizziness, and chemobrain were the most bothersome physical symptoms just after completing IC [7]. Additionally, our analysis revealed that participants were affected with an overwhelming sense of loss, fear, and uncertainty in the early phase of IC [7]. Likewise, two recent cross-sectional studies on newly diagnosed AML patients receiving IC and one longitudinal study of AML patients undergoing prolonged chemotherapy documented a high prevalence of traumatic stress symptoms, intense worrying and sadness, uncertainty about durable remission, and fear of cancer recurrence as serious threat to psychological well-being [4, 5, 8]. Correspondingly, several qualitative studies investigating patients’ perspectives on the initial phase of leukemia diagnosis, IC, and bone marrow transplantation (BMT) noted a sense of shock, emotional numbness, threat, insecurity, uncertainty, and fear regarding diagnosis, invasive procedures, cancer recurrence, and transplant rejection [9–12]. Although data from the initial phase of leukemia diagnosis and treatment may provide some guidance, additional research is needed to explore longer-term physical and psychosocial implications of leukemia and inform effective care plans to enhance quality of life in leukemia survivorship.

Coping strategies, either problem- or emotion-focused, play a pivotal role in dealing with life stressors. Problem-focused strategies tackle problems directly whereas emotion-oriented tactics manipulate overwhelming realities to regulate affective responses [13]. The significance of one’s ability to use coping strategies in response to taxing demands and the association between coping and quality of life has been previously shown [14–16]. Denial and avoidance, seeking social support, reprioritizing goals and values, and surrendering control were the common coping strategies in the early phase of leukemia diagnosis and BMT [9, 17]. However, little is known about the influence of maintenance chemotherapy on long-term physical and psychological well-being of leukemia survivors beyond the active treatment phase (usually around 6 months). Equally important, it is not clear whether the type and nature of distress and coping strategies change over time in leukemia survivorship. This knowledge would help health care providers to identify and support effective coping strategies, and address essential needs of leukemia survivors.

The purpose of this study was to explore how AML survivors describe the long-term physical and psychosocial impact of leukemia and their personal coping strategies to deal with these challenges 12 months after diagnosis. Furthermore, we explored the advice provided by these survivors to future patients on how to cope with the everyday challenges of living with leukemia.

Methods

Study design and sample

A prospective qualitative study design inspired by grounded theory (GT) methodology was used in this study [18, 19]. Employing the systematic approach of GT, this study sought to develop a theoretical explanation for the process of coping with long-term effects of leukemia [20]. Theoretical sampling, a cyclical process in which sampling and data collection are guided by data analysis, was used. Following the leads of emerging concepts, supplementary information was explored from younger and older survivors who had relevant experiences and could elaborate on the dimension and attributes of the targeted concepts [18, 21]. Constant comparative analysis was applied to create categories, discover the pattern in data, and move toward constructing a substantive theory [20].

Building upon our previous qualitative study on QOL and physical function of leukemia survivors 6 months after diagnosis [7], the present study explored survivorship issues 12 months after diagnosis. This time point was chosen because by 12 months, many patients have completed their chemotherapy and are reintegrating into society [22]. Therefore, ongoing physical issues, pre-existing and newly occurred psychosocial difficulties, and common coping strategies to deal with enduring challenges are crucial to understand.

A consecutive sampling approach was employed and participants were recruited from a pool of 236 patients taking part in an ongoing prospective cohort study on QOL and physical function of younger and older adults with AML at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network Toronto, Canada [1]. Eligible participants had to be at least 18 years old, spoke and read English sufficiently to provide informed consent and complete questionnaires, and had no significant cognitive impairment prior to starting chemotherapy. Participants were excluded if they had another active malignancy or life-threatening comorbidity, life expectancy <1 month, or were more than 12 months beyond diagnosis. Nineteen participants were interviewed. The sample size was determined by data saturation (i.e., no new themes emerge from the data, and categories and the relationships among them are well developed and supported) [23]. Of a total 25 participants who were interviewed 6 months after diagnosis, 9 were not included in the current study due to undertaking BMT (n = 5), disease relapse (n = 1), and death (n = 3). The remaining 16 participants were interviewed for the second time. To reach data saturation, three more participants, who had consented but had not been interviewed at 6 months due to reaching data saturation at that time point, were interviewed. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Data were collected using semi-structured interviews guided by topic guides (Appendix). The topic guides were developed by the research team and modified based on initial analysis. Interviews were conducted by HB at the convenience of the participants in clinic or at home. The interviews lasted on average 45 min (range 16–115 min) and took place from February 2012 to January 2013. Socio-demographic and clinical information was obtained from the patients’ charts.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. The accuracy of transcripts was checked by HB. NVivo 10.0 (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) was used to manage the data.

Data analysis was conducted using the constant comparison method [19]. Initiating with open coding, two members of the research team (VGJ and HB) analyzed the data line by line to identify concepts, discover concept properties and dimensions, and develop categories [23]. Emerging concepts and categories were then discussed with all members of the team, and a decision was made at this time to group participants in ongoing and completed treatment groups based on initial data analyses indicating differences between the groups. In the second phase of analysis, axial coding, categories and subcategories emergent from comparisons were defined and refined for each group and categories were delineated in relationship to other categories and subcategories [23]. Consensus was obtained within the team. In the third phase, selective coding, emerging categories and relationships were integrated at more abstract level to construct central themes and tentative hypotheses [23]. The process of analytic interpretation of qualitative data, defining and refining codes and categories, and developing central themes was iterative and continuous throughout data collection and analysis.

Results

A total of 19 participants, 8 men and 11 women, were interviewed. The participants’ age ranged from 27 to 71 (mean 50.5 years); the majority was married (68 %), with college/university education (63 %), and working at the time of diagnosis (47 %). The baseline characteristics of participants are depicted in Table 1. More than half of participants (58 %) had completed chemotherapy; however, 42 % of participants were on maintenance chemotherapy.

Themes

Three major themes were identified and described in detail below: ongoing impact of disease and treatment, emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies, and advice for future patients and health care providers (Table 2).

-

Theme 1: Ongoing impact of disease and treatment. This main theme encompassed two subthemes: improved versus improving health, and altered business, family, and social life.

-

Subtheme 1a: Improved versus improving health. Participants who had completed treatment expressed a feeling of recovery and satisfaction with their health. They described feeling that the most bothersome “treatment side effects had disappeared” and their “energy levels” and functional abilities had significantly improved. However, those who were still receiving treatment reported a range of bothersome health issues such as “fatigue,” “lower levels of energy,” “shortness of breath,” and “nausea and vomiting.” In spite of enduring treatment side effects and subsequent limitations in functional capacity, the ongoing treatment group appreciated the positive effects of chemotherapy and claimed that their health has been steadily improving throughout the treatment course. Furthermore, they were optimistic and expressed hope for a better health “after finishing all the medications.”

-

Subtheme 1b: Altered business, family, and social life. This was as a common theme for all participants regardless of the phase of treatment. However, the underlying factors identified by each group were different. Acute treatment side effects including fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and fear of infection were frequently reported by the ongoing treatment group as the most significant factors that negatively influenced their work and social life. In contrast, changes in interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships as a result of the leukemia diagnosis and treatment side effects were identified by participants who had completed chemotherapy. Lack of interest in communicating with people and a perceived change in identity as a “cancer survivor” were specifically described by this group as undesirable post-treatment changes with negative effects on family life, social interactions, and lifestyle.

-

-

Theme 2: Emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies. A broad range of emotion-and problem-focused coping strategies were identified. Emotion-focused coping strategies were typically used to come to terms with the unpredictable nature of survivorship, an unknown future, and the relatively poor prognosis of leukemia. Problem-focused strategies, however, were frequently reported by participants in ongoing treatment to manage side effects and subsequent functional limitations.

-

Subtheme 2a: “Keep the mind off negative things.” This was a common emotion-focused strategy employed by all. “The negative things” referred to undesirable thoughts about “illness and its negative effects” such as uncertain future. Mental disengagement was the strategy of choice to withdraw from distressing thoughts and ensuing negative emotions. In doing so, participants used alternative activities to keep busy. “Working,” either full- or part-time, was identified by many participants as the best activity to disengage the mind. However, not all survivors were able to work. Therefore, a range of simple activities including “watching TV,” “reading,” “reorganizing a room or a shelf,” “listening to news or music,” and “being around people” were used to help distract from “negative things.”

-

Subtheme 2b: Seeking control over distressing situations. A range of control-seeking strategies including “short-term planning,” wresting positive value from negative events, “appreciating each day of life as a new day,” and “enjoying little things” were described by all. “Short-term planning/goals” was mainly used to deal with an unknown future through “focusing on what they could control.” Likewise, “taking advantage of today,” “making use of all the time,” “appreciation for life,” and “enjoying little things” were tactics to restructure cognitive state and enhance perception of control. Nevertheless, a subtle difference between the groups was noted in the use of control strategies of searching for meaning and understanding and “going with the flow.” These strategies were exclusively used by participants still on treatment in an attempt to adjust to events they had appraised as uncontrollable.

-

Subtheme 2c: Seeking social support. This was another common emotion-focused coping strategy reported by all. The main reason for seeking social support was to ensure that the enduring psychological distress and emotional burden were common experiences. Participants expected to obtain moral support, acknowledgment, empathy, and understanding from their social network, including family, friends, health care providers, and other patients with leukemia. Furthermore, participants emphasized that communication with other leukemia survivors helped them validate their feelings and make sense of their emotional reactions.

Additional emotion-focused tactics including humor, turning to religion, denial, and avoidance were identified by several participants.

-

Subtheme 2d: Problem-focused strategies. Problem-focused strategies such as “resting between activities” and “writing stuff down” were frequently used to manage treatment side effects such as fatigue and memory problems. As expected, these strategies were reported mostly by the ongoing treatment group who were still dealing with treatment consequences.

-

-

Theme 3: Advice. This theme incorporated two subthemes: advice for future patients and advice for health care providers.

-

Subtheme 3a: Advice for future patients. All participants advised future patients to “keep a positive attitude,” “avoid thinking ahead of time,” “keep their mind busy doing something,” and do not hesitate to “communicate their thoughts and feelings.” Furthermore, future patients were strongly advised to take a proactive role in their treatment through “reading the written information,” “gaining knowledge about the language” of leukemia, learning “what questions to ask and how,” and “achieve capacity to comprehend the explanations” provided by health care professionals.

-

Subtheme 3b: Advice for health care providers (HCPs). This was focused on therapeutic communication, empathy, reassurance, and providing appropriate information at the right time. With regard to timely and appropriate information, our participants had two recommendations. First, HCPs were advised to be considerate of patients’ feelings and concerns, since fundamental differences can exist between what patients perceive as important and what HCPs consider as a priority. This subtle and often invisible disagreement between patients and HCPs may impact the quality and effectiveness of therapeutic communication. One suggestion was to “initiate the communication by asking patients specific questions” to learn about their understanding, needs, and priorities prior to providing information and planning education. The importance of “reassurance,” “person-to-person interactions,” and “providing consultation for personal issues” was also emphasized to establish and maintain patient-centered communication. Second, HCPs were advised not to answer patients’ questions using the phrase “everybody is different.” Participants pointed out that saying “everybody is different is not helpful; actually it is hurtful” since “no meaning could be drawn from that.” They mentioned that they “like to know about the probabilities and percentages related to the outcomes of treatment.” Therefore, they suggested HCPs “provide the patients with a list of the things that potentially could happen.” In connection with this, participants also stated that “pamphlets written by leukemia patients” could be very helpful since it can work as a communication channel to connect them to former patients and reassure them that their current feelings and concerns are expected. Despite a positive attitude toward pamphlets written by patients themselves, printed information or a binder with information was not appreciated by leukemia survivors. Generally, participants believed that the binder was “too much” or “too big” for them to read. A few patients also indicated that the written information “was not of most needed and most helpful” considering “the patients’ circumstances.” Additional advice for HCPs was about building networks and connections among leukemia survivors. “Establishing and enhancing social networks among leukemia survivors,” either in the form of “social events held in the safe environment” or through social media, along with “facilitating interactions among patients especially those around the same age” was commonly suggested. Further advice was related to the general process of hospitalization and care such as “shortening the wait time” for follow-up visits, providing “home nursing care” and “support for child care,” and “cheaper hospital parking.”

-

Comparison between 6- and 12-month results (Table 3)

A perception of ongoing improvement in health was commonly expressed by participants at 6- and-12 month interviews. Likewise, side effects reported by participants receiving maintenance chemotherapy 12 months after diagnosis were comparable to complaints reported at 6 months. Nonetheless, the symptoms of “chemobrain” were less severe and markedly less bothersome at 12 months compared to those at 6 months after diagnosis. An additional similarity was advice for future patients and health care providers. However, there was substantial difference in perceived concerns and primary challenges at two time points. Treatment side effects and physical limitations were the main issues for AML survivors 6 months after diagnosis whereas adjustment to psychosocial distress was the major challenge of participants 12 months post-diagnosis.

Discussion

Receiving a diagnosis of AML and undergoing chemotherapy are traumatic experiences burdened with enormous physical and psychological distress [4, 5, 7]. Effective coping strategies are required to adjust to life with AML [24, 25]. However, little is known about longer-term physical and psychosocial consequences of leukemia and commonly employed coping strategies. We explored how physical and psychological impacts of AML change over time in patients undertaking or completed chemotherapy, and identified coping strategies used 12 months after diagnosis by 19 survivors.

We found that treatment side effects continued to compromise physical and psychosocial well-being of participants undergoing maintenance chemotherapy. Conversely, those who completed treatment expressed considerable improvements in physical symptoms and general health. Nevertheless, their psychosocial well-being was impaired by perceived changes in their ability to initiate and maintain relationships and resume former activities. The negative effect of perceived loss of functional and mental abilities on work and social reintegration was also found in leukemia survivors 6 months after diagnosis [7]. Therefore, incorporating psychosocial interventions into survivorship care plans may be warranted to help AML survivors adjust to their limitations and new identity as leukemia survivors. Occupational therapy consultation may also be helpful for those survivors wishing to re-enter the work force.

Furthermore, problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies were employed by participants to deal with the physical and psychosocial burden of AML and chemotherapy. However, more emotion-focused strategies were used than problem-oriented approaches. Additionally, emotion-focused strategies were used to deal with situations appraised as uncontrollable whereas problem-focused tactics were employed to manage treatment side effects evaluated as controllable. This finding is in line with the “goodness of fit” hypothesis that suggests that subjective appraisal and perceived control play a key role in application of problem- or emotion-focused coping strategies [26, 27]. Interventions aimed to enhance adaptation should promote patients’ abilities to effectively use emotion- and problem-focused strategies which best match their appraisal of changeable or unchangeable situations.

Moreover, our findings showed that mental disengagement/distancing and seeking control were the most commonly used emotion-focused coping mechanisms. Interestingly, these strategies were also recommended as advice for future patients living with leukemia. These findings were consistent with our previous results [7]. Although distancing has been identified as a common strategy in previous studies on hematologic and non-hematologic malignancies and leukemia patients undergoing BMT [17, 28], some literature suggests that distancing can impede effective adaptation [29, 30]. Further research is needed to enhance our understanding of mental disengagement at various stages of leukemia survivorship.

Similarly, gaining control has been identified as an essential coping strategy in acute leukemia [10]. However, conflicting findings in the initial phase of leukemia diagnosis and treatment showed that recently diagnosed patients and those undertaking treatment preferred to surrender control to health care providers [7, 9]. While the important role of empowering patients has been emphasized in literature on adaptation to cancer [31], relinquishing control has been identified as an adaptive response in highly stressful and unknown situations [9]. Given the current inconsistent evidence and the significant role of perceived control in stress, coping, and adaptation [32], further investigation is warranted to identify personal and situational factors contributing to adaptive use of control strategies.

Seeking social support was an additional coping strategy. Although seeking social support has been identified as an important strategy to facilitate adaptation [17, 33, 34], seeking emotional support may not always be useful [35]. Venting of negative emotions and talking about unpleasant experiences may intensify negative mood states through focusing attention on negative feelings [36, 37]. Focusing on distressing emotions can impede adjustment [35]. Therefore, interventions should be planned to help survivors to move forward and beyond the distressing emotions after expressing them in a safe and accepting social environment [35].

In terms of advice for future patients, our participants recommended strategies that could be categorized as “fighting spirit,” in agreement with previous studies on leukemia patients undergoing BMT and found to be associated with improved survival [24]. Advice for HCPs was similar at both 6 and 12 months after diagnosis, and it was mainly focused on improving therapeutic communication, providing support and reassurance, and individualized and person-centered care [7].

The significant strength of this study lies in its longitudinal nature, which allowed us to explore changes in the physical and psychological burden of leukemia over time and investigate the significant role of coping strategies across survivorship. However, our findings are limited to a single tertiary cancer hospital; therefore, they may not be generalizable. Additionally, this study is limited to those who achieved complete remission (CR). Future studies should explore distress and coping in patients unable to achieve CR as well as those who opt for best supportive care or other treatment approaches. Furthermore, the relatively high attrition rate of older leukemia survivors prevented comparison of age groups at 12 months while our results at 6 months did show some differences. Future studies on long-term physical and psychological issues of living with leukemia should consider the potential role of age in affecting perception of emotional distress and use of coping mechanisms.

In conclusion, physical complications of leukemia became less bothersome overtime whereas the emotional burden of illness and treatment continued to unsettle survivors. Coping strategies play an integral role in leukemia survivorship, and interventions to enhance effective coping are crucial to improve adaptation and leukemia survivors’ quality of life.

References

Alibhai SMH et al (2015) Quality of life and physical function in adults treated with intensive chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia improve over time independent of age. J Geriatr Oncol

Saini L, Alibhai SM, Brandwein JM (2011) Quality of life issues in elderly acute myeloid leukemia patients. Aging Health 7(3):477–490

Burnett AK et al (2010) Attempts to optimize induction and consolidation treatment in acute myeloid leukemia: results of the MRC AML12 trial. J Clin Oncol 28(4):586–595

Rodin G et al (2013) Traumatic stress in acute leukemia. Psycho-Oncology 22(2):299–307

Zimmermann C et al (2013) Symptom burden and supportive care in patients with acute leukemia. Leuk Res 37(7):731–736

Zittoun R, Achard S, Ruszniewski M (1999) Assessment of quality of life during intensive chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation. Psycho-Oncology 8(1):64–73

Ghodraty-Jabloo V et al (2015) One day at a time: improving the patient experience during and after intensive chemotherapy for younger and older AML patients. Leuk Res 39(2):192–197

Schumacher A et al (1998) Quality of life in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia receiving intensive and prolonged chemotherapy—a longitudinal study. Leukemia 12(4):586–592

Nissim R et al (2013) Abducted by the illness: a qualitative study of traumatic stress in individuals with acute leukemia. Leuk Res 37(5):496–502

Papadopoulou C, Johnston B, Themessl-Huber M (2013) The experience of acute leukaemia in adult patients: a qualitative thematic synthesis. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17(5):640–648

Farsi Z, Nayeri ND, Negarandeh R (2012) The coping process in adults with acute leukemia undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Nurs Res 20(2):99–109

Nissim R et al (2014) Finding new bearings: a qualitative study on the transition from inpatient to ambulatory care of patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Support Care Cancer 22(9):2435–2443

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company, New York

Galić S, Glavić Ž, Cesarik M (2014) Stress and quality of life in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Acta Clin Croat 53(3):279–290

Van Laarhoven HWM et al (2011) Coping, quality of life, depression, and hopelessness in cancer patients in a curative and palliative, end-of-life care setting. Cancer Nurs 34(4):302–314

Dunn J et al (2006) Dimensions of quality of life and psychosocial variables most salient to colorectal cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 15(1):20–30

Farsi Z, Dehghan Nayeri N, Negarandeh R (2010) Coping strategies of adults with leukemia undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Iran: a qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci 12(4):485–492

Corbin J, Strauss A (2008) Basics of qualitative research, 3rd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Strauss A, Corbin J (1998) Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Creswell JW (2013) Qualitative inquiry research design: choosing among five approches. Third Editionb ed. Sage Publications, Inc

Patton MQ (ed) (1990) Qualitative evaluation and research methods, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Ganz PA (2006) Monitoring the physical health of cancer survivors: a survivorship-focused medical history. J Clin Oncol 24(32):5105–5111

Strauss A, Corbin J (1990) Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Newbury Park

Tschuschke V et al (2001) Associations between coping and survival time of adult leukemia patients receiving allogeneic bone marrow transplantation results of a prospective study. J Psychosom Res 50(5):277–285

Berterö C, Ek AC (1993) Quality of life of adults with acute leukaemia. J Adv Nurs 18(9):1346–1353

Park CL, Folkman S, Bostrom A (2001) Appraisals of controllability and coping in caregivers and HIV+ men: testing the goodness-of-fit hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 69(3):481–488

Park CL, Sacco SJ, Edmondson D (2012) Expanding coping goodness-of-fit: religious coping, health locus of control, and depressed affect in heart failure patients. Anxiety Stress Coping 25(2):137–153

Dunkel-Schetter C et al (1992) Patterns of coping with cancer. Health Psychol 11(2):79–87

Cronkite RC, Moos RH (1984) The role of predisposing and moderating factors in these stress-illness relationship. J Health Soc Behav 25(4):372–393

Aldwin CM, Revenson TA (1987) Does coping help? A reexamination of the relation between coping and mental health. J Pers Soc Psychol 53(2):337–348

Tariman JD et al (2010) Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 21(6):1145–1151

Folkman S (1984) Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 46(4):839–852

Cooke L et al (2009) Psychological issues of stem cell transplant. Semin Oncol Nurs 25(2):139–150

Grulke N et al (2005) Coping and survival in patients with leukemia undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation - long-term follow-up of a prospective study. J Psychosom Res 59(5):337–346

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub KJ (1989) Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 56(2):267–283

Costanza RS, Derlega VJ, Winstead BA (1988) Positive and negative forms of social support: effects of conversational topics on coping with stress among same-sex friends. J Exp Soc Psychol 24(2):182–193

Archer RL, Hormuth SE, Berg JH (1982) Avoidance of self-disclosure: an experiment under conditions of self-awareness. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 8(1):122–128

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients who enrolled in the study and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (US) that funded this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (US) (Grant number 6220–12).

Conflict of interest

Dr. Alibhai has received the research grant (6220–12) from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (US). Dr. Alibhai is a Research Scientist of the Canadian Cancer Society. Dr. Martine Puts is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health New Investigator Award. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review data if requested.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network Toronto, Canada. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee, the Tri Council Policy Statement- Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (September 1998), The International Conference on Harmonization: Good Clinical Practice (ICH:E6), Health Canada’s Food & Drug Regulations, Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) 2002, Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) 2004, US Department of Health and Human Services: Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) 2007, US Department of Health and Human Services FDA Guidance for Clinical Investigators, Sponsors, and IRBs - Adverse Event Reporting to IRB (2009), and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Appendix

Topic guide for survivorship study second interview at 12 months

Dear Mr./Mrs./Ms…

You have been participating in the “QOL and physical function in long-term AML survivors” study, for which we would like to thank you very much. We have previously talked about the consequences of the treatment of AML on your health and daily activities shortly after you completed treatment. It’s now been about 6 months since we met. We would like to talk about how you have been managing in the interim, to better understand the long-term effects of the treatments on your overall well-being. The interview will be taped so that the interview will be quicker but also so that we do not miss any important information you may wish to tell us. All of the information you give me today will be anonymous. Do you have any questions before we start?

-

1.

Could you describe how you are currently doing in terms of health since we talked last?

-

2.

Have you received any health care treatment such as surgery, medications or other things since the previous interview about 6 months ago?

-

3.

As a result of the cancer treatment you received, are there any consequences on your daily functioning that you still experience today?

-

4.

(In case they have multiple issues) could you describe which of the effects of treatment are the most bothersome, and could you describe why they are the most bothersome?

-

5.

Have you been able to get back to your previous activities prior to being diagnosed with AML (e.g., work, school, or hobbies)? Did you have to make any changes to what you used to do?

-

6.

How do these negative effects of treatment impact your daily activities? Has there been a change in your daily activities since we last saw each other? And if there has been a change, could you explain how your activities have changed? Could you describe your activities that you do in an average day?

-

7.

Could you describe what impact these treatment effects have had on your quality of life?

-

8.

Are there any things you do/have done to reduce these negative effects of treatment?

-

9.

Looking back on the period when you were receiving your cancer treatment, is there anything health care providers can do for patients like you to help reduce the long-term effects of treatment on your daily activities and quality of life?

-

10.

Looking back on the period when you were receiving your cancer treatment, is there any advice that you would give to persons starting the same treatment, to help them cope better with the treatment and reduce the impact of the treatment on their quality of life?

-

11.

In what way has having AML and going through treatment affected your view of your future?

-

12.

Are there things that you would like us to know about living with the consequences of the treatment, that we did not ask you about?

Thank you very much for your participation in this study. May we contact you (by phone/in person) in a few weeks’ time to go over the results together, to make sure we have understood and interpreted your experiences correctly?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghodraty-Jabloo, V., Alibhai, S.M.H., Breunis, H. et al. Keep your mind off negative things: coping with long-term effects of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Support Care Cancer 24, 2035–2045 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3002-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3002-4