Abstract

Background

Endoscopic resection for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus is a technically difficult procedure. We investigated clinical outcomes to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of endoscopic resection for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus.

Methods

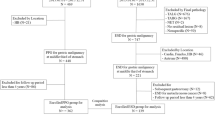

Subjects who underwent endoscopic resection for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus between January 1997 and February 2012 were eligible.

Results

A total of 227 subjects underwent endoscopic resection for 228 gastric adenomas and early cancers in the pylorus. En bloc resection was achieved for 193 lesions (84.6 %), including complete resection of 195 lesions (85.5 %), and curative resection of 167 lesions (73.2 %). Complete resection and curative resection rates were significantly different according to the location (prepyloric, pyloric, and postpyloric, P = 0.002 and P = 0.006). Delayed bleeding and stricture occurred in 5.3 and 3.1 %, respectively, and there was no patient with perforation. During a median follow-up period of 79.0 months, local tumor recurrence was detected in 2.6 %.

Conclusions

Endoscopic resection appears to be a feasible and effective method for the treatment of pyloric neoplasms, regardless of the location and distribution of tumor. Thorough evaluation of the distal margin of the tumors is necessary when tumors involve or extend beyond the pyloric ring, and the appropriate use of additional techniques may be useful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although its incidence has declined, gastric cancer remains one of the most common causes of cancer morbidity and mortality worldwide [1, 2]. Endoscopic screening of asymptomatic individuals for gastric cancer in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer such as Japan and Korea has increased the rate of detection of early gastric cancer (EGC), and 5-year overall survival now exceeds 90 % [3, 4]. Treatment options for gastric cancer have expanded, with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) regarded as a standard treatment for EGC [5–7].

Endoscopic resection (ER) of gastric neoplasms located in the pylorus is technically difficult because of the limited working space and cone-shaped anatomic feature. In addition, peristaltic contractions of peripyloric muscles adversely affect precise dissection of the lesion. Moreover, lesions involving the pyloric ring often cannot be completely visualized using a forward-viewing endoscopes and may require retroflexion in the bulb. These technical difficulties may lead to the incomplete resection of tumors, increasing the likelihood of local recurrence.

Several studies have reported that complete resection (CR) is dependent on both the location and the size of the lesion and that CR is inversely related to the incidence of local recurrence [8, 9]. Few studies reported results of ER for pyloric tumors, especially with retroflexion technique [10–12]. However, most studies regarding pyloric tumors were case series, and little is known about the clinical outcomes for ER of pyloric lesions in general. We therefore investigated the clinical outcomes of ER to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of ER for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus.

Materials and methods

Patients

Subjects who underwent ER for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus at Asan Medical Center from January 1997 to February 2012 were eligible. Patients who previously underwent gastric surgery were excluded. The medical records of these patients were reviewed, and their clinical characteristics including patient-related factors (age and sex), tumor-related factors (gross type, number of lesions, maximal dimensions of the resected specimen and tumor, and histologic differentiation), and procedure-related factors (total procedure time, resection time, hemostasis time, and adverse events) were investigated. In addition, the results of ER, the rates of local recurrence, the development of metachronous gastric neoplasm, and the overall and disease-specific survival rates were analyzed. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (2014-0525) of the Asan Medical Center.

Endoscopic resection and follow-up

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was performed until 2003, and ESD has been performed since 2004. During the EMR period, absolute indications included differentiated EGC ≤ 2 cm in diameter and small (≤1 cm) depressed EGC without ulceration or scarring. After the adoption of ESD, indications were expanded to include differentiated cancer without lymphatic or vascular involvement, mucosal cancers without ulcerative findings regardless of tumor size, mucosal cancers with ulcerative findings ≤30 mm, and minute (<500 μm from the muscularis mucosae) submucosal cancers ≤30 mm [5, 13–15].

ER was performed by one of eight experienced endoscopists, with patients under conscious sedation using intravenous midazolam and pethidine. The marking was performed on the borders of the lesions identified by conventional endoscopy or chromoendoscopy. After marking, normal saline containing small amounts of epinephrine and indigo carmine was then injected submucosally around the lesion. Occasionally, 0.4 % sodium hyaluronate diluted with normal saline and epinephrine was used instead. A small incision was made with a needle knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) followed by a circumferential mucosal incision outside the marking made using an insulated tip (IT) knife (Olympus) or needle knife. EMR was performed with circumferential precutting, followed by snare resection. Submucosal dissection was performed with an IT knife and/or needle knife. If necessary, hemostatic procedures were performed during and after submucosal dissection.

To overcome the difficulties of ER for pyloric tumors, traction methods were used in some cases. Transnasal endoscope-associated traction was performed with a transnasal endoscope operated by a second endoscopist to retract submucosal tissue to visualize the cutting line using grasping forceps, while the primary endoscopist performed the main procedure (Fig. 1) [16]. Double-channel endoscope-assisted traction was performed with a grasping forceps inserted into one channel of a double-channel endoscope to make counter traction during resection [17]. The decision to use traction methods or to attempt retroflexion was made upon by the endoscopist based on several factors, including bulb deformity, ulcer scars, and technical difficulty.

Transnasal endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure for postpyloric tumor. A Early gastric cancer identified on the pyloric ring, and the distal margin could not be visualize. B The lesion extended to the pyloric ring, as revealed by a retroflexion in the duodenal bulb. C Marking on the prepyloric area. D Marking on the postpyloric area. E Precutting on the postpyloric area. F Use of the transnasal endoscope for traction after partial submucosal dissection. G Submucosal dissection. H En bloc resected specimen

Chest radiography was performed on the same day after the procedure to identify possible complications such as perforation. Patients without perforation underwent routine second-look endoscopic examination on the second day after ER. All patients were admitted on the day before the procedure and were discharged after second-look endoscopy was performed.

Follow-up endoscopy was performed every 6–12 months during the first 2 years after the ER and annually thereafter. Patients found to have gastric adenocarcinoma were assessed by additional abdominal computed tomography scan.

Definitions

The location of the tumor was classified according to the distance from the pyloric ring: (1) prepyloric (epicenter of the tumor located in the antrum and the distal margin of the precutting line located in the pyloric ring), (2) pyloric (tumor located mainly in the prepyloric antrum, and the distal margin of the tumor was visible on the antral side of the pyloric ring), or (3) postpyloric (the distal margin of the tumor invisible on the antral side of the pylorus, including tumors with duodenal invasion beyond the pyloric ring) (Fig. 2). Pyloric and postpyloric lesions were further divided as being located in (1) the anterior wall (AW), posterior wall (PW), lesser curvature (LC), or greater curvature (GC) or (2) in the upper half (from 10 o’clock to 4 o’clock) or lower half (from 4 o’clock to 10 o’clock) of the pyloric ring with the LC of the stomach contiguous with the 12 o’clock orientation of the pylorus.

En bloc resection (EnR) was defined as resection of a lesion in one piece regardless of the depth of invasion and lymphovascular invasion. CR was defined as a lateral tumor-free margin >2 mm and a vertical tumor-free margin >0.5 mm on histologic examination. Curative resection (CuR) was defined as the absence of lymphovascular invasion or perineural invasion, and submucosal invasion <500 μm from the muscularis mucosa. Non-CuR was defined as tumors that did not fulfill the above criteria for CuR regardless of CR.

Total procedure time was measured from the beginning of marking around the tumor to the removal of the endoscope, including any time required for hemostasis. Resection time was defined as the period from marking to detachment of the resected specimen. Hemostasis time was the time required to control immediate bleeding.

Procedure-related bleeding was defined as early post-ESD bleeding when bleeding was identified by routine second-look endoscopy within 48 h or as delayed post-ESD bleeding when bleeding occurred more than 48 h after the procedure. Perforation was diagnosed endoscopically during the procedure or radiographically when chest radiography revealed free air. Stricture was defined as the gross narrowing of the pyloric canal and the presence of symptoms related to the obstruction of gastric outlet or when the resistance was felt when the endoscope was passed through the pyloric ring.

Synchronous gastric neoplasms were defined as lesions in a different location detected within 1 year of the initial ESD and metachronous neoplasms as lesions detected more than 1 year after ESD.

Statistical analysis

Differences between clinical characteristics were determined using the student’s t test or Chi-squared test, as appropriate. When the sample size was small, the Mann–Whitney U-test or Fisher’s exact test was used. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to assess survival. Factors associated with stricture were assessed using a logistic regression model, with odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (Chicago, IL, USA), and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic features of gastric neoplasms

During the study period, a total of 227 subjects underwent ER for 228 gastric adenomas and early cancers in the pylorus (Table 1). The median age was 62 years [interquartile range (IQR): 53–68 years], and the male-to-female ratio was 2.2:1. The median tumor size in resected specimens was 14 mm (IQR: 10–22 mm). Of the 228 lesions, 145 (63.6 %) were pathologically diagnosed as adenoma and 83 (36.4 %) as EGC, with the latter including 76 differentiated and seven undifferentiated adenocarcinomas. Of the tumors, 218 (95.6 %) were confined to the mucosal layer, whereas 10 (4.4 %) invaded the submucosa, with three lesions further invaded the deep submucosal layer (≥500 μm from the muscularis mucosa).

Clinical outcomes of endoscopic resection

EMR and ESD were performed in 78 lesions (34.2 %) and 150 lesions (65.8 %), respectively (Table 2). The median procedure time was 23 min (IQR: 15–33 min). Traction methods were used for 37 lesions (16.3 %); double-channel endoscope-assisted traction was used in 35 lesions, and transnasal endoscope-assisted traction was used in two. Retroflexion was performed in 21 lesions (9.2 %), and a traction method and retroflexion were used together for five lesions (2.2 %).

EnR was achieved during removal of 193 of 228 lesions (84.6 %), with CR achieved for 195 lesions (85.5 %), and CuR for 167 lesions (73.2 %). Of the 167 lesions showing CuR, local recurrence was detected in two patients: One was treated with ER and one with surgical resection. As for the 61 cases with non-CuR, two patients underwent subsequent surgery, with pathologic evaluation after gastrectomy revealing no residual tumor. The remaining patients were followed up by endoscopy, with local recurrence detected in four patients: Of these, two patients underwent gastrectomy, one was treated with argon plasma coagulation, and one patient underwent ER. Of the three patients with deep submucosal invasion, one patient underwent surgical resection, whereas the other two were observed because of their advanced age (Fig. 3).

Adverse events occurred in 19 patients, including delayed bleeding (n = 12, 5.3 %) and stricture (n = 7, 3.1 %). All patients with delayed bleeding were treated endoscopically. When the circumference of the lesion exceeded 3/4 of the pyloric ring, the risk of stricture increased significantly (OR 80.0, 95 % CI 4.96–1,290.11, P = 0.002). Pyloric strictures not allowing passage of the endoscope developed in three patients, with one undergoing distal gastrectomy, one treated by pyloric stent insertion, and one undergoing repeated balloon dilatation. No patient experienced perforations after the procedure.

At a median follow-up of 79.0 months (range 3.7–201.7 months), 24 patients had died. Of the 83 patients with EGC, two died of gastric neoplasm-related causes (distant metastasis and cancer-related complication), and 11 died of unrelated causes, including hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal cancer, lung cancer, and pneumonia. The 5-year overall and disease-specific survival rates were 81.5 and 96.9 %, respectively (Fig. 4).

Outcomes of endoscopic resection according to the location of the tumor

Based on the distance from the pyloric ring, 81 tumors were located in the prepyloric area, 74 in the pyloric area, and 73 in the postpyloric area (Table 3). Tumors involving or located beyond the pyloric ring more frequently required additional techniques, such as traction methods and retroflexion. EnR rate of postpyloric lesions tended to be associated with the use of additional techniques (P = 0.077), whereas CR (P = 0.564) and CuR (P = 0.263) rates were not. CR and CuR rates were significantly lower for pyloric and postpyloric than for prepyloric lesions (P = 0.002 and P = 0.006), whereas the local recurrence rates did not differ. When we compared the outcomes for pyloric neoplasms resected by ESD, CuR rates were 89.4, 82.2, and 65.5 % for prepyloric, pyloric, and postpyloric lesions, respectively (P = 0.010).

Of the 147 pyloric and postpyloric lesions, 46 (31.3 %) each were located in the AW and PW, 42 (28.6 %) in the LC, and 13 (8.8 %) in the GC. In addition, 81 lesions (55.1 %) were located in the upper half and 66 (44.9 %) in the lower half of the pyloric ring. Neither set of locations, however, was significantly associated with EnR, CR, and CuR rates.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the clinical outcomes of ER for neoplasms in the pylorus. EnR, CR, and CuR rates were 84.6, 85.5, and 73.2 %, respectively, and the local tumor recurrence rate was 2.6 % during a median follow-up period of 79.0 months. CR and CuR rates were significantly lower for pyloric and postpyloric lesions than for prepyloric lesions. Adverse events followed the removal of 19 lesions, including delayed bleeding (5.3 %) and stricture (3.1 %). As for 83 patients with EGC, the 5-year overall survival and disease-specific survival rates were 81.5 and 96.9 %, respectively. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to evaluate clinical outcomes and the effectiveness of ER for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus.

Although ESD increased the EnR rate, ER for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus is technically difficult because of the limited working space and unique anatomic feature. These technical difficulties may lead to the incomplete resection of tumors, increasing the likelihood of local recurrence. Moreover, lesions involving the pyloric ring cannot be entirely visualized using forward-viewing endoscopes and may require retroflexion in the bulb, which requires advanced skill and experience. However, retroflexion is not always possible because of the narrow space or a duodenal scar, and a forced attempt may increase the risk of perforation. Because of these anatomical characteristics, performing ER with a conventional forward-viewing endoscope may not assure CR of the distal margin of the tumor, especially when the lesions involve the duodenal bulb beyond the pyloric ring [10, 11, 18]. ESD was recently reported to be successful for the removal of gastric neoplasms located in the pyloric ring with or without duodenal invasion, especially with an attempt of a retroflexion technique, and perforation related to retroflexion in the duodenal bulb has rarely been reported [10–12]. In our study, retroflexion was performed during the removal of 9.2 % of all lesions, including 27.4 % of postpyloric lesions. However, use of the retroflexion technique was not related to either the CR or CuR rate.

With regard to location of pyloric tumors, CR rate was reported lowest for tumors located in the 12–3 o’clock quadrant and upper hemisphere [19]. Regarding the direction of the knife, with working channels located at 7 o’clock position, it may have been more difficult to appropriately delineate the distal margin of lesions located in the LC, AW, or in the upper half of the pyloric ring. Additional techniques were used in some cases, such as the traction method with a transnasal or double-channel endoscope. EnR rate tended to be higher when one of these additional techniques was used; however, the association was not statistically significant (P = 0.077). When analyzing the result of ER according to the hemispheric and quadrant distribution of the lesion, neither set of locations was significantly associated with EnR, CR, and CuR rates.

The increased use of ESD has made EnR more possible for large tumors and tumors located in more difficult locations. However, the technical difficulties required to ensure sufficient safety margins during ER resulted in lower CuR rates for lesions involving or extending beyond the pyloric ring than for lesions located in other areas of the stomach [15, 18]. We found that the overall CuR rate was 73.2 % and that both CR and CuR rates were significantly lower for pyloric and postpyloric than for prepyloric lesions. When we compared the outcomes for pyloric neoplasms resected by ESD, CuR rate was 78.0 % for overall and 89.4, 82.2, and 65.5 % for prepyloric, pyloric, and postpyloric lesions, respectively (P = 0.010). These results suggest that the distal margin of the tumors involving or extending beyond the pyloric ring should be evaluated and resected thoroughly.

No major procedure-related complications, such as perforation or significant bleeding that required transfusion, were noted. The low rate of perforation might be due to the anatomic structure of the pylorus with a muscular ring composed of a thickened portion of the circular layer of the muscular coat [20]. Procedure-related stricture was associated with an iatrogenic ulcer after the resection of large tumor near the pylorus. The reported risk factors for the stricture are circumferential extent of the mucosal defect of > 3/4 or longitudinal extent of >5 cm [21–23]. In the present study, stricture occurred in 3.1 % of all lesions and 43.8 % of the lesions with the circumferential extent exceeded 3/4 of the total circumference of the pyloric ring. In agreement with previous reports, we found that the risk of stricture increased when the circumference of the lesion exceeded 3/4 of the total circumference of the pyloric ring.

This study has several limitations. First, because it is a retrospective study conducted in a single center, there may have been a selection bias in deciding to perform ESD, especially during the initial period of ER. Second, clinical outcomes may have been influenced by the endoscopists’ experience because ER is an operator-dependent procedure.

In conclusion, ER for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus is feasible and effective, with favorable clinical and long-term outcomes regardless of the location and distribution of pyloric tumor. Thorough evaluation of the distal margin of the tumors is necessary when tumors involve or extend beyond the pyloric ring, and the appropriate use of additional techniques may be useful in these patients.

References

Crew KD, Neugut AI (2006) Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 12:354–362

Jung KW, Park S, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee JY, Seo HG, Lee JS (2012) Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2012. Cancer Res Treat 44:25–31

Everett SM, Axon AT (1997) Early gastric cancer in Europe. Gut 41:142–150

Kong SH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Jung HC, Lee KU, Choe KJ, Yang HK (2004) Clinicopathologic features of asymptomatic gastric adenocarcinoma patients in Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol 34:1–7

Ahn JY, Jung HY, Choi KD, Choi JY, Kim MY, Lee JH, Choi KS, Kim DH, Song HJ, Lee GJ, Kim JH (2011) Endoscopic and oncologic outcomes after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: 1370 cases of absolute and extended indications. Gastrointest Endosc 74:485–493

Gotoda T (2007) Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 10:1–11

Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T (2005) Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 23:4490–4498

Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, Fujiki S, Takata R, Yoshino T, Shiratori Y (2006) Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy 38:987–990

Takenaka R, Kawahara Y, Okada H, Hori K, Inoue M, Kawano S, Tanioks D, Tsuzuki T, Yagi S, Kato J, Uemura M, Ohara N, Yoshino T, Imagawa A, Jujiki S, Takata R, Yamamoto K (2008) Risk factors associated with local recurrence of early gastric cancers after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc 68:887–894

Jung SW, Jeong ID, Bang SJ, Shin JW, Park NH, Kim DH (2010) Successful outcomes of endoscopic resection for gastric adenomas and early cancers located on the pyloric ring (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 71:625–629

Lim CH, Park JM, Park CH, Cho YK, Lee IS, Kim SW, Choi MG, Chung IS (2012) Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasia involving the pyloric channel by retroflexion in the duodenum. Dig Dis Sci 57:148–154

Park JC, Kim JH, Youn YH, Cheoi K, Chung H, Kim H, Lee H, Shin SK, Lee SK, Kim H, Park H, Lee SI, Lee YC (2011) How to manage pyloric tumours that are difficult to resect completely with endoscopic resection: comparison of the retroflexion vs. forward view technique. Dig Liver Dis 43:958–964

Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y (2000) Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer 3:219–225

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2011) Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd english edition. Gastric Cancer 14:101–112

Shimada Y, JGCA (The Japan Gastric Cancer Association) (2004) Gastric cancer treatment guidelines. Jpn J Clin Oncol 34:58

Ahn JY, Choi KD, Choi JY, Kim MY, Lee JH, Choi KS, Kim DH, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY, Kim JH (2011) Transnasal endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric adenoma and early gastric cancer in the pyloric area: a case series. Endoscopy 43:233–235

Oyama T (2012) Counter traction makes endoscopic submucosal dissection easier. Clin Endosc 45:375–378

Brandt LJ, Gotian A (2002) Retroflexion in the duodenum for evaluation of duodenal bulb lesions. Gastrointest Endosc 55:438–440

Bae JH, Kim GH, Lee BE, Kim TK, Park DY, Baek DH, Song GA (2014) Factors associated with the outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection in pyloric neoplasms. Gastrointestinal endoscopy (Epub ahead of print)

Clemente CD (1985) Gray’s anatomy of the human body. Lea & Febigerr, Philadelphia

Coda S, Oda I, Gotoda T, Yokoi C, Kikuchi T, Ono H (2009) Risk factors for cardiac and pyloric stenosis after endoscopic submucosal dissection, and efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation treatment. Endoscopy 41:421–426

Iizuka H, Kakizaki S, Sohara N, Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Okamura S, Itoh H, Mori M (2010) Stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers and adenomas. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc 22:282–288

Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M (2009) Predictors of postoperative stricture after esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial squamous cell neoplasms. Endoscopy 41:661–665

Disclosures

Eun Jeong Gong, Do Hoon Kim, Hwoon-Yong Jung, Young Kwon Choi, Hyun Lim, Kwi-Sook Choi, Ji Yong Ahn, Jeong Hoon Lee, Kee Don Choi, Ho June Song, Gin Hyug Lee, and Jin-Ho Kim declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Eun Jeong Gong and Do Hoon Kim have contributed equally to this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, E.J., Kim, D.H., Jung, HY. et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic resection for gastric neoplasms in the pylorus. Surg Endosc 29, 3491–3498 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4099-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4099-8