Abstract

Ticks are considered the second most important vectors of pathogens worldwide, after mosquitoes. This study provides a systematic review of vector-host relationships between ticks and mammals (domestic and wild) and consolidates information from studies conducted in Colombia between 1911 and 2020. Using the PRISMA method, 71 scientific articles containing records for 51 tick species (Argasidae and Ixodidae) associated with mammals are reported. The existing information on tick-mammal associations in Colombia is scarce, fragmented, or very old. Moreover, 213 specimens were assessed based on morphological and molecular analyses, which allowed confirming eight tick species associated with mammals: Amblyomma calcaratum, Amblyomma dissimile, Amblyomma mixtum, Amblyomma nodosum, Amblyomma ovale, Amblyomma varium, Ixodes luciae, and Ixodes tropicalis. Several tick species are molecularly confirmed for Colombia and nine new relationships between ticks and mammals are reported. This research compiles and confirms important records of tick-mammal associations in Colombia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ticks are considered the second most important vectors of pathogens, after mosquitoes (Anderson 2002; Anderson and Magnarelli 2008; de la Fuente et al. 2008; Cortés-Vecino 2018). Tick fauna currently comprises approximately 955 species belonging to three families, namely, Ixodidae (736 species), Argasidae (218 species), and Nuttalliellidae (1 species) (Dantas-Torres et al. 2019). Local tick diversity is attributed to the variety of thermal floors and plant diversity, which facilitate plasticity in these arachnids for colonizing diverse habitats (Guglielmone et al. 2003a, 2010; Estrada-Peña 2008). Approximately one-fourth of known tick species are found in the Neotropical region and nearly 70–80% of their hosts are mammals (Nava et al. 2008, 2017; Hornok et al. 2016; Labruna et al. 2016). The family Ixodidae includes species of medical and veterinary importance since these transmit a variety of bacteria (e.g., Coxiella, Borrelia, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia), protozoa (e.g., Theileria), and viruses (e.g., Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus) (Sonenshine 2018; Cabezas-Cruz et al. 2019; Rizzoli et al. 2019). Accordingly, mammals are epidemiologically important in pathogen-vector-host interactions due mainly to their habitats, areas of occupation, physiology, and body size (Monsalve et al. 2009; Heine et al. 2017). Several small- and medium-sized mammals are potential reservoirs of tick-borne pathogens; however, it is uncertain if they have a direct role as vectors in the transmission of infectious agents (Larson et al. 2018; Mlera and Bloom 2018).

In Colombia, there are records on the occurrence of 58 tick species. According to the last review on Neotropical ticks (Guglielmone et al. 2003a), concerning 15 species of Argasidae and 37 species of Ixodidae, Ixodes fuscipes was excluded from the list of valid species for Colombia based on findings by Labruna et al. (2020). In addition, four species were reported for the country: Amblyomma parvum Aragão, 1908 (López and Parra 1985; confirmed by Nava et al. 2017), Ixodes affinis Neumann, 1889 (Mattar and López-Valencia 1998), Ixodes auritulus Neumann, 1904 (González-Acuña et al. 2005), and Dermacentor imitans Warburton, 1933 (Guglielmone et al. 2006). Nava et al. (2014) reevaluated the taxonomic status of A. cajennense and concluded that this taxon actually comprised six valid species, among which A. cajennense sensu stricto was not found in Colombia in the samples examined, and only Amblyomma patinoi Labruna, Nava, and Beati, 2014, and Amblyomma mixtum Koch, 1844, were confirmed for the country (Nava et al. 2014; Rivera-Páez et al. 2016). Apanaskevich and Bermúdez (2017) reported Ixodes bocatorensis Apanaskevich and Bermúdez 2017, in Colombia and, according to Bermúdez et al. (2015), the occurrence of I. brunneus needs to be confirmed.

In Colombia, many tick species are associated with small- and medium-sized wild and domestic mammals; however, several of these records raise uncertainty (Cortés-Vecino et al. 2010; Miranda et al. 2011; Faccini-Martínez et al. 2017; Acevedo-Gutiérrez et al. 2020). Despite the epidemiological importance and role of ticks in the transmission and circulation of infectious diseases, in Colombia, the literature records on ectoparasites associated with wild mammals are scarce and fragmented (Torres-Mejía and de la Fuente 2006; Londoño et al. 2017; Rivera-Páez et al. 2018; Acevedo-Gutiérrez et al. 2020). Given this, a comprehension of the dynamics of zoonosis (i.e., causes, factors, and mammals involved) is relevant to any country and contributes to understanding emerging and re-emerging tick-borne diseases (Betancur et al. 2015). Thus, this study provides an exhaustive review of tick-mammal relationships reported in specialized literature, as well as new reports of this type of relationship in Colombia to consolidate the information on ticks associated with mammals in the country.

Materials and methods

Systematic review

To gather the information on ticks associated with mammals in Colombia and provide new records, we reviewed the information available in the literature retrieved from Science Direct, Web of Science, SciELO Scopus, and Google Scholar search engines using the keywords ((Colombia*) AND (Tick*) AND (Ixodidae*) OR (Argasidae*)), without temporal restrictions (n = 2940) (1911—August of 2020). A total of 71 documents were compiled and selected, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method (Moher et al. 2009, 2012; Urrútia and Bonfill 2010). The information was complemented with suggested references on ectoparasites of mammals of Colombia (Gonzalez-Astudillo et al. 2016). Updated lists of mammals in Colombia were used to update mammal names and synonymies (Solari et al. 2013; Ramírez-Chaves et al. 2016, 2018). Tick taxonomy was determined according to Dantas-Torres et al. (2019).

Tick identification and new records

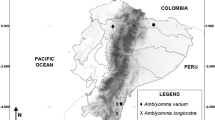

A morphological analysis was performed on 213 ticks collected during samplings conducted in the departments of Antioquia, Caldas, and Cundinamarca (Colombia) between 2015 and 2018. The ticks were identified to the species level following the dichotomous keys of Robinson (1926), Aragão and Fonseca (1961), Jones et al. (1972), Barros-Battesti et al. (2006), Melhorn (2008), Nava et al. (2014, 2017), and Dantas-Torres et al. (2019), using a light microscope. Furthermore, a molecular analysis was performed to confirm the morphological identifications of the tick species. Twenty-two samples were analyzed, which included at least one individual from each morphotype per host and collection site. DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR amplification of fragments from two mitochondrial genes, namely, the 5′ region of the cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene with primers LCO1490 (F) 5’-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′ and HCO2198 (R) 5’-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′ (Folmer et al. 1994), and the 16S rDNA gene using primers F 5′– CTGCTCAATGATTTTTTAAATTGCTGTGG–3′ and R 5′– CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCAAGT-3′ (Norris et al. 1996), was performed. The amplicons were purified and sent to Macrogen (Geumcheon-gu, Seoul, South Korea) for Sanger sequencing. The sequences were assessed and edited using Geneious Trial v8.14 (Drummond et al. 2009). Furthermore, the sequences were searched against public databases, including GenBank and BOLD (Barcode of Life Data Systems, www.barcodinglife.com), using BLAST.

Results

In this review, 51 tick species are reported in association with mammals in Colombia (also includes records of Amblyomma cajennense s.l.). The ticks belong to the families Ixodidae (39 species) and Argasidae (12 species). Among these, 25 ectoparasite species (16 ixodids and 9 argasids) are reported exclusively in at least 42 wild mammal species. In Colombia, 18 species of hard ticks (Ixodidae) interact with at least 10 domestic mammal species; two are associated with one hybrid (Equus caballus x E. asinus); three species are reported from three exotic-invasive species (Mus musculus, Rattus rattus, and R. norvegicus); 18 are associated with domestic and wild mammals; and one species (Dermacentor imitans) is reported exclusively from humans (Table 1).

A total of 213 tick specimens (133 adults, 43 nymphs, and 37 larvae) were collected from 19 host individuals belonging to six mammalian orders: one individual of Didelphis marsupialis and one Monodelphis adusta (Didelphimorphia), two Tamandua mexicana (Pilosa), three Cerdocyon thous (Carnivora), five Equus caballus (Perissodactyla), three Homo sapiens (Primates), and three Heteromys anomalus and one Nectomys grandis (Rodentia). All ticks were morphologically examined and adults and nymphs were identified. In total, eight species were recorded: Amblyomma calcaratum, Amblyomma dissimile, Amblyomma mixtum, Amblyomma nodosum, Amblyomma ovale, Amblyomma varium, Ixodes luciae, and Ixodes tropicalis. Larvae were identified to the genus level. The hosts and collection localities for each tick species are shown in Table 2. After the morphological identification, molecular methods were used to confirm the identity of A. calcaratum (one female and one male), A. dissimile (three males), A. mixtum (one female and one male), A. nodosum (two females), A. ovale (one female and one male), A. varium (one female and two larvae), I. luciae (four females), and I. tropicalis (one female and three nymphs).

From the samples collected, nine new relationships between ticks and mammals in Colombia were established, including eight new relationships between hard ticks and wild mammals. Furthermore, the first record of A. varium parasitizing humans is reported for Colombia. Records of A. calcaratum and I. tropicalis were molecularly confirmed, providing updated information for these species since previous reports were outdated (Table 2). The partial nucleotide sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers [MN879555 – MN879567] for the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene, and [MT000155 – MT000161] for the COI gene. The voucher specimens were deposited in the Collection of Ectoparasites of the Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad de Caldas (Ramírez-Chaves et al. 2019).

Discussion

The current information on tick-mammal associations for Colombia comprises records of 51 tick species associated with wild and domestic, exotic, human mammal hosts. This review consolidated information on mammals in Colombia in the last century, concerning their association with ticks and changes in tick-mammal relationships throughout this period (Guglielmone et al. 2003a, 2006, 2014; Guglielmone and Robbins 2018; Nava et al. 2017). Species such as Amblyomma incisum Neumann, 1906; Amblyomma pecarium Dunn, 1933; Amblyomma tigrinum Koch, 1844; and Ixodes loricatus Neumann, 1899, as well as other tick species reported by López-Valencia (2017), are recorded in association with mammals in Colombia (Acevedo-Gutiérrez et al. 2020). The confirmation of these species would broaden the list of valid species in Colombia. However, Guglielmone et al. (2011) and Guglielmone and Robbins (2018) did not report these species in Colombia. In this study, these species were not considered since their records must be confirmed and they can be confused with other species.

The morphological confirmation and generation of new genetic sequences of ticks associated with mammals in Colombia allowed inferring the state of the knowledge on these interactions in the country compared with other countries in America (Nava et al. 2014; Rivera-Páez et al. 2018; Dantas-Torres et al. 2019). We highlight the need to review and support several vector-host relationships between ticks and mammals in Colombia (e.g., Amblyomma geayi with Bradypus variegatus; Haemaphysalis leporispalustris with Homo sapiens). Especially, there are several outdated records and morphological and molecular confirmations are needed for several species according to new studies in America (e.g., Labruna et al. 2020; Onofrio et al. 2020) that describe new tick species, synonymies, and reinstatement of species. In addition, new records of Ixodes species from Colombia, which yielded DNA sequences lacking high identity (≤ 95%) to any species in GenBank (Martínez-Sánchez et al. 2020).

Moreover, several mammal species, such as Dasypus novemcinctus, D. marsupialis, Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris, Myrmecophaga tridactyla, and Tamandua tetradactyla, are associated with a high species richness of ticks (14 species), which agrees with reports for other Neotropical countries (Muñoz-García et al. 2019; Nava et al. 2017). Furthermore, several associations were specific; for example, Sigmodon alstoni is exclusively associated with a single tick species (Amblyomma auricularium). These specific relationships were reported in other countries of the American continent (Wells et al. 1981; Lopes et al. 2016).

This study reports the first record for Colombia of A. varium from humans; particularly, this species rarely parasitizes humans and has only been confirmed in this association in Panama and Costa Rica (Guglielmone and Robbins 2018). Among 39 hard tick species associated with mammals in Colombia, according to Guglielmone and Robbins (2018), eight species are confirmed parasitizing humans: A. dissimile, A. mixtum, A. oblongoguttatum, A. ovale, D. imitans, D. nitens, R. microplus, and R. sanguineus s. l. Furthermore, Guglielmone and Robbins (2018) did not include H. leporispalustris in the list of species that parasitize humans in Colombia, although Osorno Mesa (1940) found a nymph of Haemaphysalis proxima Aragão on a human from Colombia, and this name is treated as a synonym of H. leporispalustris by Camicas et al. (1998) and others. However, this synonymy was not accepted by Guglielmone and Nava et al. (2014), who classified H. proxima as a nomen dubium. In this study, the record from Osorno-Mesa (1940) is included in Table 2. In addition to providing the first record of A. varium parasitizing humans in Colombia, this study also gathered records for Amblyomma patinoi, Amblyomma sabanerae, Ornithodoros puertoricensis (Quintero et al. 2020), and Ornithodoros rudis (Dunn 1929; Osorno-Mesa 1940; Jones et al. 1972) parasitizing humans in Colombia. Overall, 14 out of 51 tick species associated with mammals were found parasitizing humans in the Colombian territory.

A large fraction of these tick species comprises endemic vectors of pathogens with global epidemiological impact in recent decades (Guglielmone et al. 2003a, 2006, 2014; Estrada-Peña 2008; Barros-Battesti et al. 2013; Nava et al. 2017; López-Valencia 2017; Dantas-Torres et al. 2019; Acevedo-Gutiérrez et al. 2020). On this basis, the study of tick-borne pathogens in Colombia requires greater sampling efforts since many tick species reported in Colombia are confirmed vectors of infectious pathogens of medical and veterinary importance (McCown et al. 2014; Osorio et al. 2018; Santodomingo et al. 2019). Research on this topic should include wildlife, exotic, and domestic mammals as a whole.

References

Acero EJ, Calixto OJ, Prieto AC (2011) Garrapatas (Acari: Ixodidae) prevalentes en caninos no migrantes del noroccidente de Bogotá, Colombia. NOVA 9(16):158–165

Acevedo-Gutiérrez LY, Pérez-Pérez JC, Paternina LE, Londoño AF, López G, Rodas JD (2020) Garrapatas duras (Acari: Ixodidae) de Colombia, una revisión a su conocimiento en el país. Acta Biol Colombiana 25(1):126–139

Anderson JF (2002) The natural history of ticks. Med Clin North Am 86(2):205–218

Anderson JF, Magnarelli LA (2008) biology of ticks. Infect Dis Clin N Am 22:195–215

Apanaskevich DA, Bermúdez SE (2017) Description of a new species of Ixodes Latreille, 1795 (Acari: Ixodidae) and redescription of I. lasallei Múndez & Ortiz, 1958, parasites of agoutis and pacas (Rodentia: Dasyproctidae, Cuniculidae) in Central and South America. Syst Parasitol 94:463–475

Apanaskevich DA, Domínguez LG, Torres SS, Bernal JA, Montenegro VM, Sergio E, Bermúdez SE (2017) First description of the male and redescription of the female of Ixodes tapirus Kohls, 1956 (Acari: Ixodidae), a parasite of tapirs (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) from the mountains of Colombia, Costa Rica and Panama. Syst Parasitol 94:413–422

Aragão HB, Fonseca F (1961) Notas de ixodologia. V. A proposito da validade de algumas espécies do gênero Amblyomma do continente americano (Acari: Ixodidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 51:485–492

Araque A, Ujueta S, Bonilla R, Gómez D, Rivera J (2014) Resistencia a acaricidas en Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus de algunas explotaciones ganaderas de Colombia. Revista UDCA Actualidad & Divulgación Científica 17(1):161–170

Armed Forces Pest Management Board (1998) Defense Pest Management Information Analysis Center. In: Disease Vector Ecology Profile. Departament of defense, Colombia, p 89

Barros-Battesti DM, Arzua M, Bechara GH (2006) Carrapatos de importância médico veterinária da região neotropical: Um guia ilustrado para identificação de espécies. Vox/ICTTD-3/Butantan, São Paulo, p 223

Barros-Battesti DM, Ramirez DG, Landulfo GA, Faccini JLH, Dantas-Torres F, Labruna MB, Venzal JM, Onofrio VC (2013) Immature argasid ticks: diagnosis and keys for Neotropical region. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 22(4):443–456

Benavides-Montaño JA, Jaramillo-Cruz CA, Mesa-Cobo NC (2018) Garrapatas Ixodidae (Acari) en el Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Boletín Científico Centro de Museos Museo de Historia Natural 22(1):131–150

Bermúdez SE, Torres S, Aguirre Y, Domínguez L, Bernal Veja JA (2015) A review of Ixodes (Acari Ixodidae) parasitizing wild birds in Panama, with the first records of Ixodes auritulus and Ixodes bequaerti. Syst Appl Acarol 20:847–853

Betancur H, Betancourt E, Giraldo R (2015) Importance of ticks in the transmission of zoonotic agents. Revista MVZ Córdoba 20:5053–5067

Cabezas-Cruz A, Estrada-Peña A, de la Fuente J (2019) The good, the bad and the tick. Front Cell Dev Biol 7(71):1–5

Camicas J-L, Hervy J-P, Adam F, Morel P-C (1998) Les tiques du monde (Acarida, Ixodida). Nomenclature, stades décrits, hôtes, répartition. ORSTOM, Paris, pp 233

Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical - CIAT (1973) Annual Report 1973. Available from: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/65072. Accessed 26 Aug 2020

Cooley RA (1944) Ixodes montoyanus (Ixodidae) a new tick from Colombia. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam 23:804–806

Corrier DE, Cortes JM, Thompson KC, Riaño H, Becerra E, Rodríguez R (1978) A field survey of bovine anaplasmosis, babesiosis and tick vector prevalence in the eastern plains of Colombia. Trop Anim Health Prod 10:91–92

Cortés-Vecino JA (2018) Control integrado de garrapatas y su importancia en salud pública. Biomédica 38(4):452–455

Cortés-Vecino JA, Echeverri JAB, Cárdenas JA, Herrera LAP (2010) Distribución de garrapatas Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus en bovinos y fincas del Altiplano cundiboyacense (Colombia). Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria 11(1):73–84

Cotes-Perdomo AP, Oviedo A, Castro LR (2020) Molecular detection of pathogens in ticks associated with domestic animals from the Colombian Caribbean región. Exp Appl Acarol 82:137–150

Dantas-Torres F, Martins TF, Muñoz-Leal S, Onofrio VC, Barros-Battesti DM (2019) Ticks (Ixodida: Argasidae, Ixodidae) of Brazil: updated species checklist and taxonomic keys. Ticks Tick-Borne Diseases 10(6):1–45

de la Fuente J, Estrada-Peña A, Venzal JM, Kocan KM, Sonenshine DE (2008) Overview: ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Front Biosci 13:6938–6946

Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Cheung M, Heled J, Kearse M, Moir R, Stones HS, Thierer T, Wilson A (2009). Geneious v8.14. http://www.geneious.com (Accessed 19 August 2019)

Dunn LH (1929) Notes on some insects and other arthropods affecting man and animals in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1(6):493–508

Durden LA, Keirans JE (1994) Description of the larva, diagnosis of the nymph and female based on scanning electron microscopy, hosts, and distribution of Ixodes venezuelensis. Med Vet Entomol 8(4):310–316

Estrada-Peña A (2008) Climate, niche, ticks, and models: what they are and how we should interpret them. Parasitol Res 103(1):87–95

Faccini-Martínez ÁA, Costa FB, Hayama-Ueno TE, Ramírez-Hernández A, Cortés-Vecino JA, Labruna MB, Hidalgo M (2015) Rickettsia rickettsii in Amblyomma patinoi ticks, Colombia. Emerg Infect Dis 21(3):537–539

Faccini-Martínez ÁA, Ramírez-Hernández A, Forero-Becerra E, Cortés-Vecino JA, Escandón P, Rodas JD, Palomar AM, Portillo A, Oteo JA, Hidalgo M (2016) Molecular evidence of different Rickettsia species in Villeta, Colombia. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Diseases 16(2):85–87

Faccini-Martínez ÁA, Ramírez-Hernández A, Barreto C, Forero-Becerra E, Millán D, Valbuena E, Sánchez-Alfonso AC, Imbacuán-Pantoja WO, Cortés-Vecino JA, Polo-Terán LJ, Yaya-Lancheros N, Jácome J, Palomar AM, Santibáñez S, Portillo A, Oteo JA, Hidalgo M (2017) Epidemiology of spotted fever group rickettsioses and acute undifferentiated febrile illness in Villeta, Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 97(3):782–788

Fairchild GB, Kohls GM, Vernon JT (1966) The ticks of Panama. In: Wenzel R, Tipton V (eds) Ectoparasits of Panama. Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, pp 167–219

Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R (1994) DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol 3:294–299

Gómez GF, Isaza JP, Segura JA, Alzate JF, Gutiérrez LA (2020) Metatranscriptomic virome assessment of Rhipicephalus microplus from Colombia. Ticks Tick-Borne Diseases 11(5):1–9

González-Acuña D, Venzal JM, Keirans JE, Robbins RG, Ippi S, Guglielmone AA (2005) New host and locality records for the Ixodes auritulus (Acari: Ixodidae) species group, with a review of host relationships and distribution in the Neotropical Zoogeographic Region. Exp Appl Acarol 37:147–156

Gonzalez-Astudillo V, Ramírez-Chaves HE, Henning J, Gillespie TR (2016) Current knowledge of studies of pathogens in Colombian mammals. MANTER: Journal of Parasite Biodiversity 4:1–13

Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG (2018). Hard ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) parasitizing humans: a global overview. Springer international publishing 314p

Guglielmone AA, Estrada-Peña A, Keirans JE, Robbins RG (2003a) Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of the neotropical zoogeographic region. In: In: Special Publication of the Integrated Consortium on Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases-2. Houten, Atalanta

Guglielmone AA, Estrada-Peña A, Luciani CA, Mangold AJ, Keirans JE (2003b) Hosts and distribution of Amblyomma auricularium (Conil 1878) and Amblyomma pseudoconcolor Aragão, 1908 (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol 29:131–139

Guglielmone AA, Beati L, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB, Nava S, Venzal JM, Mangold J, Szabó MPJ, Martins JR, González-Acuña D, Estrada-Peña A (2006) Ticks (Ixodidae) on humans in South America. Exp Appl Acarol 40(2):83–100

Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG, Apanaskevich DA, Petney TN, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG, Shao R, Barker SC (2010) The Argasidae, Ixodidae and Nuttalliellidae (Acari: Ixodida) of the world: a list of valid species names. Zootaxa 2528(6):1–28

Guglielmone AA, Nava S, Díaz M (2011) Relationships of south American marsupials (Didelphimorphia, Microbiotheria and Paucituberculata) and hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) with distribution of four species of Ixodes. Zootaxa 3086:1–30

Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG, Apanaskevich DA, Petney TN, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG (2014) The hard ticks of the world: (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae). Springer Dordrecht, Heidelberg, p 738

Heine KB, DeVries PJ, Penz CM (2017) Parasitism and grooming behavior of a natural white-tailed deer population in Alabama. Ethol Ecol Evol 29(3):292–303

Hornok S, Görföl T, Estók P, Tu VT, Kontschán J (2016) Description of a new tick species, Ixodes collaris n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae), from bats (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae, Rhinolophidae) in Vietnam. Parasit Vectors 9(1):332

Jaimes-Dueñez J, Triana-Chávez O, Holguín-Rocha A, Tobon-Castaño A, Mejía-Jaramillo AM (2018) Molecular surveillance and phylogenetic traits of Babesia bigemina and Babesia bovis in cattle (Bos taurus) and water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) from Colombia. Parasit Vectors 11 (510): 1–12

Jones EK, Clifford CM, Keirans JE, Kohls GM (1972) The ticks of Venezuela (Acarina: Ixodoidea) with a key of species of Amblyomma in the Western Hemisphere Brigham Young University. Sci Bull Biol Series 17:1–11

Keirans JE (1973) Ixodes (I.) montoyanus Cooley (Acarina: Ixodidae): first description of the male and immature stages, with records from deer in Colombia and Venezuela. J Med Entomol 10(3):249–254

Keirans JE, Brewster BE (1981) The Nuttall & British Museum (Natural History) tick collections: lectotype designations for ticks (Acarina: Ixodoidea) described by Nuttall, Warburton, Cooper & Robinson. Bull Zool Ser-Br Museum (Natural History) Dept Zool 41(4):153–178

Kohls GM (1953) Ixodes venezuelensis, a new species of tick from Venezuela, with notes on Ixodes minor Neumann, 1902 (Acarina: Ixodidae). J Parasitol 39(3):300–303

Kohls GM (1956) Eight new species of Ixodes from central and South America (Acarina: Ixodidae). J Parasitol 42(6):636–649

Kohls GM (1960) Records and new synonymy of New World Haemaphysalis ticks, with descriptions of the nymph and larva of H. juxtakochi Cooley. J Parasitol 46(3):355–361

Kohls GM, Sonenshine DE, Clifford CM (1965) The systematics of the subfamily Ornithodorinae (Acarina: Argasidae) II Identification of the larvae of the Western Hemisphere and descriptions of three new species. Ann Entomol Soc Am 58(3):331–364

Kohls GM, Clifford CM, Jones EK (1969) The systematics of the subfamily Ornithodorinae (Acarina: Argasidae) IV Eight new species of Ornithodoros from the Western Hemisphere. Ann Entomol Soc Am 62(5):1035–1043

Labruna MB, Keirans JE, Camargo LMA, Ribeiro AF, Soares RM, Camargo EP (2005) Amblyomma latepunctatum, a valid tick species (Acari: Ixodidae) long misidentified with both Amblyomma incisum and Amblyomma scalpturatum. J Parasitol 91(3):527–541

Labruna MB, Soares JF, Martins TF, Soares HS, Cabrera RR (2011) Cross-mating experiments with geographically different populations of Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol 54:41–49

Labruna MB, Nava S, Marcili A, Barbieri AR, Nunes PH, Horta MC, Venzal JM (2016) A new argasid tick species (Acari: Argasidae) associated with the rock cavy, Kerodon rupestris Wied-Neuwied (Rodentia: Caviidae), in a semiarid region of Brazil. Parasit Vectors 9(1):511

Labruna MB, Onofrio VC, Barros-Battesti DM, Gianizella SL, Venzal JM, Guglielmone AA (2020) Synonymy of Ixodes aragaoi with Ixodes fuscipes, and reinstatement of Ixodes spinosus (Acari: Ixodidae). Ticks Tick Dis 11(101349):1–9

Larson SR, Lee X, Paskewitz SM (2018) Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in two species of Peromyscus mice common in northern Wisconsin. J Med Entomol 55(4):1002–1010

Londoño AF, Díaz FJ, Valbuena G, Gazi M, Labruna MB, Hidalgo M, Mattar S, Contreras V, Rodas JD (2014) Infection of Amblyomma ovale by Rickettsia sp. strain Atlantic rainforest, Colombia. Ticks Tick-Borne Diseases 5(6):672–675

Londoño AF, Acevedo-Gutiérrez LY, Marín D, Contreras V, Díaz FJ, Valbuena G, Labruna MB, Hidalgo M, Arboleda M, Mattar S, Solari S (2017) Wild and domestic animals likely involved in rickettsial endemic zones of Northwestern Colombia. Ticks Tick-Borne Diseases 8(6):887–894

Lopes MG, Junior JM, Foster RJ, Harmsen BJ, Sanchez E, Martins TF, Quigley H, Marcili A, Labruna MB (2016) Ticks and rickettsiae from wildlife in Belize, Central America. Parasit Vectors 9(1 62):1–7

López G (1980) Bioecología y distribución de garrapatas en Colombia. En: Control de garrapatas. Medellín: Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario, Compendio No 39:33–43

López GV, Parra D (1985) Amblyomma neumanni, Ribaga 1902. Primera comprobación en Colombia y claves para las especies de Amblyomma. Revista ICA 20:152–162

López LA, López AG, Gonzalez EF (1975) Bovine babesiosis and anaplasmosis: control by premunition and chemoprophylaxis. Exp Parasitol 37:92–104

López-Valencia G (2017) Garrapatas (Acari: Ixodidae y Argasidae) de importancia médica y veterinaria procedentes de norte, centro y sur América. Antioquia. Editorial Universidad CES- Universidad de Antioquia: 210 p

Luque G (1948) Amblyomma nodosum en Tamandua tetradactyla. Rev Med Vet Zoot 17(97):119–120

Luque G (1949) Amblyomma oblongogutatum sobre la piel de un campesino en la región selvática de Barrancabermeja. Rev Med Vet Zoot 18(99):213–214

Marinkelle CJ, Grose ES (1981) A list of ectoparasites of Colombian bats. Rev Biol Trop 29(1):11–20

Martínez-Sánchez ET, Cardona-Romero M, Ortiz-Giraldo M, Tobón-Escobar WD, Moreno D, Ossa-López PA, Pérez-Cárdenas JE, Labruna MB, Martins TF, Rivera-Páez FA, Castaño-Villa GJ (2020) Associations between wild birds and hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Colombia. Ticks Tick Borne 11(6):101534 1-8

Mattar S, López-Valencia G (1998) Searching for Lyme disease in Colombia: a preliminary study on the vector. J Med Entomol 35:324–326

McCown ME, Alleman A, Sayler KA, Chandrashekar R, Thatcher B, Tyrrell P, Stillman B, Beall M, Barbet AF (2014) Point prevalence survey for tick-borne pathogens in military working dogs, shelter animals, and pet populations in northern Colombia. J Special Oper Med 14(4):81–85

Miranda J, Mattar S (2014) Molecular detection of Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia sp. strain Colombianensi in ticks from Cordoba, Colombia. Ticks Tick-borne Diseases 5(2):208–212

Miranda J, Mattar S (2015) Molecular detection of Anaplasma sp. and Ehrlichia sp. in ticks collected in domestical animals, Colombia. Trop Biomed 32(4):726–735

Miranda J, Contreras V, Negrete Y, Labruna MB, Mattar S (2011) Vigilancia de la infección por Rickettsia sp. en capibaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) un modelo potencial de alerta epidemiológica en zonas endémicas. Biomédica 31:216–221

Mlera L, Bloom ME (2018) The role of mammalian reservoir hosts in tick-borne flavivirus biology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8(298):1–10

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) The PRISMA group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097 1-6

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P (2012) Establishing a new journal for systematic review products. Syst Rev 1(1):1–3

Monsalve BS, Mattar S, González TM (2009) Zoonosis transmitidas por animales silvestres y su impacto en las enfermedades emergentes y reemergentes. Revista MVZ Córdoba 14(2):1762–1773

Muñoz-García CI, Guzmán-Cornejo C, Rendón-Franco E, Villanueva-García C, Sánchez-Montes S, Acosta-Gutierrez R, Romero-Callejas E, Díaz-López H, Martínez-Carrasco C, Berriatua E (2019) Epidemiological study of ticks collected from the northern tamandua (Tamandua mexicana) and a literature review of ticks of Myrmecophagidae anteaters. Ticks Tick-Borne Diseases 10(5):1146–1156

Muñoz-Rivas G (1973) Environmental mycobacteria in armadillos in Colombia. Revista Investigación en Salud Pública 33:61–66

Nava S, Szabó MP, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2008) Distribution, hosts, 16S rDNA sequences and phylogenetic position of the Neotropical tick Amblyomma parvum (Acari: Ixodidae). Ann Trop Med Parasitol 102(5):409–425

Nava S, Beati L, Labruna MB, Cáceres AG, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2014) Reassessment of the taxonomic status of Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius, 1787) with the description of three new species, Amblyomma tonelliae n. sp., Amblyomma interandinum n. sp. and Amblyomma patinoi n. sp., and reinstatement of Amblyomma mixtum, Koch, 1844, and Amblyomma sculptum, Berlese, 1888 (Ixodida: Ixodidae). Ticks Tick-borne Diseases 5(3):252–276

Nava S, Venzal JMM, González-Acuña DG, Martins TFF, Guglielmone AA (2017) Ticks of the southern cone of America: diagnosis, distribution, and hosts with taxonomy, ecology and sanitary importance. In ticks of the southern cone of America: diagnosis, distribution, and hosts with taxonomy, ecology and sanitary importance (1st). Elsevier, London, San Diego

Neumann LG (1911) Ixodidae. Vol. 26. R. Friedlander und sohn

Norris DE, Klompen JSH, Keirans JE, Black WC (1996) Population genetics of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 16S and 12S genes. J Med Entomol 33:78–89

Onofrio VC, Guglielmone AA, Barros-Battesti DM, Gianizella SL, Marcili A, Quadros RM, Marquesh S, Labruna MB (2020) Description of a new species of Ixodes (Acari: Ixodidae) and first report of Ixodes lasallei and Ixodes bocatorensis in Brazil. Ticks Tick-Borne Diseases 11(2020):101423 1-9

Osorio M, Miranda J, Gonzalez M, Mattar S (2018) Anaplasma sp., Ehrlichia sp., and Rickettsia sp. in ticks: a high risk for public health in Ibagué, Colombia. Kafkas Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi 24(4):557–562

Osorno-Mesa E (1940) The ticks of Colombia. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 4(13):6–24

Ospina-Pérez EM, Mancilla-Agrono LY, Rivera-Páez FA (2020) Germ cells: a useful tool for the taxonomy of Rhipicephalus sanguineus s.l. and species of the Amblyomma cajennense complex (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasitol Res 119:1573–1582

Paternina-Tuirán LE, Díaz-Olmos Y, Paternina-Gómez M, Bejarano EE (2009) Canis familiaris, un nuevo hospedero de Ornithodoros (A.) puertoricensis Fox, 1947 (Acari: Ixodida) en Colombia. Acta Biol Colombiana 14(1):153–160

Quintero JC, Londoño AF, Díaz FJ, Agudelo-Flórez P, Arboleda M, Rodas JD (2013) Ecoepidemiología de la infección por rickettsias en roedores, ectoparásitos y humanos en el noroeste de Antioquia. Colombia 33(supl. 1):38–51

Quintero VJC, Paternina TLE, Uribe YA, Muskus C, Hidalgo M, Gil J, Cienfuegos AV, Osorio L, Rojas C (2017) Eco- epidemiological analysis of rickettsial seropositivity in rural areas of Colombia: a multilevel approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(9):1–19

Quintero VJC, Mignone J, Osorio QL, Cienfuegos-Gallet AV, Rojas AC (2020) Housing conditions linked to tick (Ixodida: Ixodidae) infestation in rural areas of Colombia: a potential risk for Rickettsial transmission. J Med Entomol 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjaa159

Ramírez-Chaves HE, Suárez-Castro AF, González-Maya JF (2016) Cambios recientes a la lista de los mamíferos de Colombia. Mammal Notes 3(1):1–9

Ramírez-Chaves HE, Suárez-Castro AF, Zurc D, Concha-Osbahr DC, Trujillo A, Noguera-Urbano EA, Pantoja-Peña GE, Rodríguez-Posada ME, González-Maya JF, Pérez-Torres J, Mantilla-Meluk H, López-Castañeda C, Velásquez-Valencia A, Zárrate-Charry D (2018) Mamíferos de Colombia. Version 1.5. Sociedad Colombiana de Mastozoología. Checklist dataset accessed via GBIF.org on 2019-04-29. https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.jlqepv

Ramírez-Chaves HE, Ortíz-Giraldo M, Tobón-Escobar WD, Velásquez-Guarín D, Mejía-Fontecha IY, Ossa-López PA, Rivera-Páez FA (2019) Museo de Historia Natural, Colección de Vertebrados e Invertebrados - Colección de Ectoparásitos. Universidad de Caldas. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15472/4xysd5 accessed via GBIF.org on 2020-01-13

Reyes R (1938) Parásitos de los animales domésticos en Colombia. Rev Med Vet Zoot 8(71):17–29

Ríos-Tobón S, Gutiérrez-Builes LA, Ríos-Osorio LA (2014) Assessing bovine babesiosis in Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus ticks and 3 to 9-month-old cattle in the middle Magdalena region, Colombia. Pesq Vet Bras 34(4):313–319

Rivera B, Aycardi ER (1985) Epidemiological evaluation of external parasites in cattle from the Brazilian Cerrado and the Colombian Eastern Plains. Zentralbl Veterinar Med B 32:417–424

Rivera-Páez FA, Labruna MB, Martins TF, Sampieri BR, Camargo-Mathias MI (2016) Amblyomma mixtum Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae): first record confirmation in Colombia using morphological and molecular analyses. Ticks Tick-borne Diseases 7(5):842–848

Rivera-Páez FA, Sampieri BR, Labruna MB, da Silva MR, Martins TF, Camargo-Mathias MI (2017) Comparative analysis of germ cells and DNA of the genus Amblyomma: adding new data on Amblyomma maculatum and Amblyomma ovale species (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasitol Res 116:2883–2892

Rivera-Páez FA, Labruna MB, Martins TF, Perez JE, Castaño-Villa GJ, Ossa-López PA, Gil CA, Sampieri B, Aricapa-Giraldo HJ, Camargo-Mathias MI (2018) Contributions to the knowledge of hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in Colombia. Ticks Tick-borne Diseases 9(1):57–66

Rizzoli A, Tagliapietra V, Cagnacci F, Marini G, Arnoldi D, Rosso F, Rosà R (2019) Parasites and wildlife in a changing world: the vector-host- pathogen interaction as a learning case. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildlife 9:394–401

Robinson LE (1926) Ticks; a monograph of the Ixodoidea. Part IV. The Genus Amblyomma. London: Cambridge University, 302 p

Santodomingo A, Sierra-Orozco K, Cotes-Perdomo A, Castro LR (2019) Molecular detection of Rickettsia spp., Anaplasma platys and Theileria equi in ticks collected from horses in Tayrona National Park, Colombia. Exp Appl Acarol 77(3):411–423

Solari S, Muñoz-Saba Y, Rodríguez-Mahecha JV, Defler TR, Ramírez-Chaves HE, Trujillo F (2013) Riqueza, endemismo y conservación de los mamíferos de Colombia. Mastozoología neotropical 20(2):301–365

Sonenshine D (2018) Range expansion of tick disease vectors in North America: implications for spread of tick-borne disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(3):478

Torres-Mejía AM, de la Fuente J (2006) Risks associated with ectoparasites of wild mammals in the department of Quindío, Colombia. Int J Appl Res Vet Med 4(3):187–192

Trapido H, Sanmartín C (1971) Pichindé virus: a new virus of the Tacaribe group from Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 20(4):631–641

Urrútia G, Bonfill X (2010) Declaración PRISMA: una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med Clin 135(11):507–511

Venzal JM, Nava S, Hernández LV, Miranda J, Marcili A, Labruna MB (2018) A morphological and phylogenetic analysis of Ornithodoros marinkellei (Acari: Argasidae), with additional notes on habitat and host usage. Exp Appl Acarol 76(2):249–261

Voltzit OV (2007) A review of Neotropical Amblyomma species (Acari: Ixodidae). Acarina. 15(1):3–134

Wells EA, d'Alessandro A, Morales GA, Angel D (1981) Mammalian wildlife diseases as hazards to man and livestock in an area of the llanos Orientales of Colombia. J Wildl Dis 17(1):153–162

Wenzel RL, Tipton VJ (1966) Ectoparasites of Panama. Field Museum of Natural History

Funding

This project was funded by the Vice-rectory of Research and Post-graduate Studies of Universidad de Caldas and Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation of Colombia - Minciencias [code: 112777758193, contract 858 of 2017].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This research was conducted with the approval of the Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences – Universidad de Caldas (June 2nd of 2017) and under a framework permit granted to Universidad de Caldas by the Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales (ANLA) of Colombia (resolution 02497 of December 31 of 2018).

Additional information

Section Editor: Domenico Otranto

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ortíz-Giraldo, M., Tobón-Escobar, W.D., Velásquez-Guarín, D. et al. Ticks (Acari: Ixodoidea) associated with mammals in Colombia: a historical review, molecular species confirmation, and establishment of new relationships. Parasitol Res 120, 383–394 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-020-06989-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-020-06989-6