Abstract

Purpose

The Sunnybrook facial grading system (SFGS) is one of the most widely employed tools to assess facial function. The present study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of the Spanish language version of the SFGS.

Methods

Forward–backward translation from the original English version was performed by fluent speakers of English and Spanish. Videos from 65 patients with facial paralysis (FP) were evaluated twice by five otolaryngologists with experience in FP evaluation. Internal consistency and intra- and inter-rater reliability were assessed. The House–Brackmann scale was used to display concurrent validity which was established by Spearman’s rho correlation.

Results

The Cronbach’s α score exceeded 0.70. The intra-rater intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was nearly perfect for the composite score (0.96–0.99), voluntary movements (0.97–0.99), and synkinesis (0.91–0.98), and important to almost perfect for symmetry at rest (0.79–0.97). In both evaluations, the inter-rater ICC was higher than 0.90 for the composite score (0.92–0.96) and voluntary movements (0.91–0.96) and slightly lower for symmetry at rest (0.66–0.85) and synkinesis (0.72–0.87). A strong negative correlation was found between the H–B scale and SFGS (Spearman’s rho coefficient = − 0.92, p < 0.001) in both evaluations.

Conclusion

The Spanish version of the SFGS is a reliable and valuable instrument for the assessment of facial function in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with FP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Facial palsy is a common disease which is characterized by functional limitations in the mimic muscles. Affected individuals often have impaired facial expression of emotions, ocular problems due to incomplete eye closure, as well as aesthetic impairments.

Standardization of facial functional assessment is essential to the management of facial paralysis. Standardized assessment facilitates the follow-up of the course of recovery and response to interventions in a reproducible and accurate manner. Although video or photo documentation can be used to assess facial function, a standardized facial function grading instrument can improve the reporting of outcomes, as well as facilitate communication and comparison among specialists [1]. Multiple instruments are available, but their usage varies based on individual or institutional preferences.

Among surgeons, the most commonly used grading system is the House–Brackman (H–B) scale, which was introduced in 1985 and was originally created to assess facial recovery after vestibular schwannoma surgery [2]. It is a ranked scale which grades facial function from 1 (normal function) to 6 (total paralysis). Although widely used, it has been criticized on several grounds, including its lack of synkinesis evaluation and its low sensitivity to detect regional changes.

The Sunnybrook facial grading system (SFGS) is a reliable, sensitive, and validated scale used to determine facial symmetry at rest, voluntary facial movements, and synkinesis. It was introduced in 1996 by Ross et al. [3] and has become one of the most widely used assessment tools, particularly among rehabilitation therapists [1]. In this scale, a final score of 0 to 100 is calculated, wherein 0 indicates total paralysis and 100 indicates normal function.

Despite the fact that Spanish is spoken by more than 500 million people—one of the five most spoken languages in the world—to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no Spanish language version of the SFGS. Consequently, the psychometric properties of the SFGS have not been established among Spanish physicians, preventing the widespread use of this instrument in the Spanish-speaking population.

In order to resolve this, an effort has been made to translate the SFGS into a Spanish-language version using cross-cultural adaptation measures [4]. In the present study, we assessed the internal consistency and validity of the Spanish version of the SFGS in a cohort of 65 patients with facial palsy.

Methods

Subjects

The present study enrolled 65 consecutive patients seen at the facial palsy clinic of La Paz University Hospital between January and July of 2021. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of our hospital (approval code PI-4599). Inclusion criteria for the study included adults affected by acute or chronic unilateral peripheral FP. All levels of severity and all etiologies were accepted. All patients gave written informed consent for images registration and for the use of their data in this study. Patients with sequential or simultaneous bilateral palsy were not enrolled, nor were those who did not consent to participate in the study.

Spanish SFGS

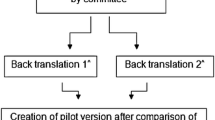

Cross-cultural adaptation measures were used to translate the SFGS into the Spanish version prior to the beginning of the study [4]. A forward–backward translation method was used to translate the SFGS into Spanish. Translation was performed by two Spanish researchers who were fluent in both English and Spanish, and then back-translated into English by a native English-speaking translator. Any significant discrepancies were resolved, and a final Spanish version was established (Fig. 1).

To evaluate symmetry at rest, scores are obtained for the appearance of the palpebral fissure, the nasolabial fold and the corner of the mouth. As in the original version, the Spanish SFGS compares the paralyzed side with the normal side. These scores are summed together, and the summed score is multiplied by 5. This subscale ranges in value from 0 to 20.

The voluntary movement scale assesses the degree of muscle excursion when elevating the eyebrows, closing the eyes gently, snarling, smiling with the mouth open and puckering the lips. Each expression reflects the function of the 5 peripheral branches of the nerve and is graded on a scale from 1 to 5. These scores are summed together, and the summed score is multiplied by 4. This subscale ranges in value from 0 to 100.

Finally, involuntary movement contraction or synkinesis associated with each of the previous movements is graded from 0 (no synkinesis) to 3 (disfiguring synkinesis or gross mass movement of several muscles). This subscale ranges in value from 0 to 15.

The total or composite score is calculated by subtracting both the resting symmetry and synkinesis scores from the voluntary movement score, and ranges from 0 to 100 [3].

Video recording and evaluation of facial paralysis

Video and photography recordings were used to assess the severity of facial paralysis according to the standard recommendations of the Sir Charles Bell Society [5]. These recordings were taken during routine visits to the Department of Otolaryngology. All patients were recorded while sitting in the same position and in the same room, with a luminous environment and a uniform background.

Video recordings were viewed and rated using the H–B and SFGS scales by five Spanish otolaryngologists with varying levels of experience in facial palsy. One training session was provided, wherein each scale was analysed in detail, and during which 4 patients who were not included in the study were evaluated and discussed.

The five raters analyzed all the photographs and videotapes, and graded the facial function of each patient using the H–B and Spanish SFGS in two independent session: the first one was named t0, and the second one (t15) was performed between 14 and 21 days later.

Analyses

Continuous variables were expressed using mean ± standard deviation, and with ranges. Discrete variables were expressed using number and percentage.

The reliability of the SFGS was determined using Cronbach’s α and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). An α coefficient of 0.70 or higher was considered reliable. The ICC type A and type C were used for examination of the intra- and inter-rater reliability. An ICC 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was also used. In line with Landis and Koch [6], we considered agreement to be weak if rated within 0–0.40, moderate within 0.41–0.60, important within 0.61–0.80, and excellent within 0.81–0.99.

Validity was tested using Spearman’s rho correlation analysis in the examination of the numerical variables that were obtained in SFGS and H–B. In all of the analyses, p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Subjects

Among the 65 patients, the age at presentation ranged from 20 to 88 years, with a mean age of 49 years. 34 patients presented with right FP (52.3%) and 31 with left FP (47.7%). The duration of paralysis at evaluation ranged from 1 to 468 months, with a mean of 38 months. The most common etiology of FP was Bell’s palsy (27.7%), followed by other etiologies (21.5%), Ramsay-Hunt syndrome (18%), vestibular schwannoma surgery (16.9%), facial nerve tumour (6.2%), post-traumatic (4.6%), malignant neoplasia (3.1%), and cholesteatoma (1.5%). Figure 2 summarizes the composite SFGS scores obtained for the 65 patients evaluated by the five raters during the two rounds.

SFGS composite score for the 65 patients using the Spanish version of the scale. First (blue) and second (green) evaluation of each video by the five evaluators are represented. Upper and lower quartiles are represented as black boxes, and median values as vertical lines. Higher scores reflect better facial function

Consistency and reproducibility of the Spanish SFGS

The internal consistency of the Spanish SFGS according to Cronbach’s α was 0.73 for the first session and 0.74 for the second session. The intra-rater reproducibility is shown in Table 1. Based on the ICC results, excellent correlation was determined by all raters in the composite score as well as in voluntary movement and synkinesis. Only one rater had an ICC of less than 0.9 in any scale, which was 0.79 in the symmetry at rest scale. Three out of five raters had an intraclass correlation of 0.99 in the total SFGS score.

At the first evaluation, the inter-rater reproducibility for the Spanish SFGS scales were 0.78 for symmetry at rest, 0.95 for voluntary movement, 0.79 for synkinesis, and 0.94 for the total score (Table 2). At the second evaluation, the values were 0.74 for symmetry at rest, 0.94 for voluntary movement, 0.81 for synkinesis, and 0.94 for the total score.

The item with the lowest inter-rater correlation was the evaluation of the eye at rest, which was 0.52 for both the first and evaluation sessions. The item with the highest correlation was the forehead wrinkle, which was 0.94 for both the first and evaluation sessions.

Comparison of the Spanish SFGS with the H–B scale

For the concurrent validity, the results of the SFGS were compared with those of the H–B scale, since this scale was used for psychometric analysis in other publications previously. For all raters, a strongly negative correlation was observed between the Spanish SFGS and the H–B scale, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

The SFGS was described in English in 1996 [3]. Since then, it has been translated and validated into Italian [7], French [8], German [9], and Turkish [10]. It has been suggested to be the best scale for widespread clinical use by health professionals of all levels [1]. Nevertheless, as a scale administered by the rater according to their own clinical experience, it remains a subjective instrument.

For cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the SFGS, it is required not only to be linguistically appropriate for evaluating FP patients and conceptually equivalent to the original, it is also essential to present valid psychometric properties and cross-cultural measurement equivalence. This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the SFGS. Our preliminary psychometric analysis provides support for its use among professionals involved in the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of FP patients.

In this study, the Spanish SFGS provided a high degree of reliability in evaluating facial function. A high degree of internal consistency according to Cronbach’s α was demonstrated. Intra- and inter-rater reliability were evaluated using the ICC in order to provide comparability with previous studies and allow a comparison of outcomes. When evaluating the intra-rater repeatability, we found an almost perfect correlation for the composite score [0.98, (0.94–0.99)], as other studies have previously shown [11, 12]. Within the subscales, we found a high repeatability with an excellent correlation in all cases. Only one rater presented an important-to-excellent correlation at symmetry at rest. Inter-rater reliability was almost perfect for the subscales of voluntary movement, and was important for symmetry and synkinesis. These correlation results are slightly higher than those presented in the literature. This may be due to the fact that raters underwent training in the use of the scale prior to its use with the experimental cohort, or the fact all raters in the current study have experience in facial function evaluation.

In general, all variants of the SFGS have found a high degree of inter-rater correlation for voluntary movement [7,8,9,10,11], and correlation for all other movements were almost perfect, although lip pucker showed a slightly lower correlation. However, we found a weak-to-important correlation for resting symmetry (mean 0.78 at the first session and 0.74 at the second), even worse than synkinesis, which is generally the subscale found to have the lowest correlation [7, 8, 11]. Palpebral fissure was found to have worst inter-rater correlation. This may be due to the fact that some raters may have regarded the eyelid exposure as normal when the symmetry was nearly perfect. In some cases, this represents a difference of just one millimetre, but this item accounts for 5 points out of 20 in the final symmetry at rest score.

Regarding the synkinesis subscale, the Italian [7] and French [8] groups found that the most difficult item to assess was the presence of synkinesis when raising the eyebrows [mean 0.58 (0.42–0.74) and mean 0.77 (0.58–0.89), respectively]. For the Turkish group, the lowest synkinesis correlation was found for the open mouth smile [mean 0.37(− 0.50 to 0.83)] [10]. In our study, the movement of the snarl showed the lowest ICC [mean 0.53 (0.42–0.65)]. In agreement with other authors, we believe that this relatively lower level of correlation is due to the fact that when evaluating synkinesis, the rater observes the whole face, and not all raters focus on the same regions or features. This is in contrast to the evaluation of voluntary movement, where the rater’s attention is directed to a particular region of the face.

Finally, as other authors have shown [13], a strong negative correlation can be seen between the H–B and the Spanish version of the SFGS, with a Spearman Rho correlation close to − 1 (p < 0.001). When the facial palsy is more severe, the H–B scale increases, while the composite score of the SFGS decreases. The fact that our results strongly follow this correlation supports the validity of this version of the SFGS.

Conclusion

The Spanish version of the SFGS was found to be a useful and accessible instrument for Spanish-speaking physicians involved in the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with FP. The results of this study show that the Spanish version is a reproducible scale with high validity and repeatability, similar to other international versions. The use of reliable and validated Spanish-language assessment tools can improve the reliability and robustness of communication between professionals.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Fattah AY, Gavilán J, Hadlock TA, Marcus JR, Marres H, Nduka C, Slattery WH, Snyder-Warwick AK (2014) Survey of methods of facial palsy documentation in use by members of the Sir Charles Bell Society. Laryngoscope 124:2247–2251. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24636

House JW, Brackmann DE (1985) Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 93:146–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/019459988509300202

Ross BG, Fradet G, Nedzelski JM (1996) Development of a sensitive clinical facial grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:380–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0194-5998(96)70206-1

Acquadro C, Conway K, Girourdet C, Mear I (2004) Linguistic validation manual for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments. MAPI ResearchTrust, Lyon, p 184 (ISBN: 2-9522021-0-9)

Santosa KB, Fattah A, Gavilán J, Hadlock TA, Snyder-Warwick AK (2017) Photographic standards for patients with facial palsy and recommendations by members of the sir charles bell society. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 19:275–281. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1883

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174

Pavese C, Tinelli C, Furini F, Abbamonte M, Giromini E, Sala V, De Silvestri A, Cecini M, Dalla Toffola E (2013) Validation of the Italian version of the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System. Neurol Sci 34:457–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-012-1025-x

Waubant A, Franco-Vidal V, Ribadeau Dumas A (2021) Validation of a French version of the Sunnybrook facial grading system. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 17:S1879-7296(21)00181–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2021.08.003

Neumann T, Lorenz A, Volk GF, Hamzei F, Schulz S, Guntinas-Lichius O (2017) Validation of the German version of the sunnybrook facial grading system. Laryngorhinootologie 96:168–174. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-111512

Mengi E, Kara CO, Ardiç FN, Tümkaya F, Barlay F, Çil T, Şenol H (2020) Validation of the Turkish version of the Sunnybrook facial grading system. Turk J Med Sci 50:478–484. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1905-195

Cabrol C, Elarouti L, Montava AL, Jarze S, Mancini J, Lavieille JP, Barry P, Montava M (2021) Sunnybrook facial grading system: intra-rater and inter-rater variabilities. Otol Neurotol 42:1089–1094. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003140

Kanerva M, Poussa T, Pitkäranta A (2006) Sunnybrook and House-Brackmann facial grading systems: intrarater repeatability and interrater agreement. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135:865–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2006.05.748

Kanerva M, Jonsson L, Berg T, Axelsson S, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Engström M, Pitkäranta A (2011) Sunnybrook and House-Brackmann systems in 5397 facial gradings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144:570–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599810397497

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Patrick Connolly for edited a version of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant (PI20/01032) from Programa Estatal de Generación de Conocimiento y Fortalecimiento del Sistema Español de I + D + I, ISCiii, Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee CEICC La Paz University Hospital (PI-4599 11 de febrero de 2021).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanchez-Cuadrado, I., Mato-Patino, T., Morales-Puebla, J.M. et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Sunnybrook facial grading system. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 280, 543–548 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-022-07484-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-022-07484-7