Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the 5-year recurrence-free survival and prognostic factors of odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) from a single-center retrospective cohort in the northeastern region of Brazil.

Methods

Forty cases of OKC comprised the study population. In the cohort analyzed, 18 (45%) cases were recurrent OKCs and 22 (55%) were non-recurrent OKCs. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the period from the release of the histopathological report to the occurrence of relapse or last visit to the service.

Results

Comparison of the clinicopathological variables between primary and recurrent OKC lesions revealed no differences in the frequency of epithelial thickness, presence of satellite cysts and cystic spaces, presence of an inflammatory infiltrate, locularity, and lesion borders. The frequency of symptoms was practically the same even after recurrence. Satellite cysts were more frequent in the group of recurrent lesions (n = 9, p = 0.002) and the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate was also significantly associated with recurrent lesions (n = 15, p = 0.006). Previous decompression or marsupialization was associated with recurrence of the lesion (p = 0.010).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the most significant prognostic factors were previous decompression or marsupialization, as well as, morphological parameters associated with the recurrence cases were the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate and satellites cysts. The risk of recurrence is low but continues due to the particularities of epithelial proliferation in OKC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) is a benign cystic lesion that arises from remnants of the dental lamina [1,2,3]. This lesion may occur sporadically or associated with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome), which is caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor gene PTCH1 [4]. OKCs associated with Gorlin syndrome usually develop multiple lesions in the jaws and tend to occur in uncommon sites when compared to sporadic cases [5].

OKCs require special attention because of their aggressive behavior and tendency for recurrence [6]. Several treatment modalities are available, which are generally classified as conservative or aggressive. In general, “conservative” treatment consists of enucleation and/or marsupialization, while “aggressive” treatments include enucleation combined with adjunct therapies or resection [7]. Recurrence ranges from 0 to 62% after treatment, and most cases of relapse occur within the first 5 years after surgery [8]. There is no sufficient evidence in the literature to support one treatment modality as the most effective in reducing morbidity and recurrence rates, probably because of the lack of standardization of the procedure and methodological flaws [7].

Given the above, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the 5-year recurrence-free survival and prognostic factors of OKC in patients attending a referral center for oral diagnostics in the northeastern region of Brazil.

Methods

Sample selection

A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted. The population consisted of patients diagnosed with OKC between January 2007 and January 2019. The patients were submitted to surgical treatment (conservative or not) for removal of the cystic lesion at a surgery and traumatology service in Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, UFRN (Approval no.: 3.223.477/2019). All participants agreed to participate in the study by signing the free informed consent form.

The patients were recruited by searching the Registry of Excisional Biopsy Records of the Laboratory of Pathological Anatomy, Discipline of Oral Pathology, Department of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). The medical records of patients registered at the service of the Oral-Maxillofacial Surgery and Traumatology Sector were also evaluated because of the possibility that the patient had sought the service immediately before or after the diagnosis was established.

Forty cases of OKC were identified and comprised the study population. Only cases with sufficient material for morphological analysis and solitary lesions in the jaws were included. Patients with Gorlin syndrome, i.e., multiple jaw lesions, were excluded since it is difficult to differentiate recurrent lesions from new lesions in patients with multiple lesions.

We collected 5-year (60 months) follow-up data from all patients included in the study by revising the surgical records. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the period from the release of the histopathological report to the occurrence of relapse or last visit to the service. Patients who developed recurrences after 5 years and those lost to follow-up were censored.

The following variables were analyzed: age at diagnosis, skin color (white, brown or black), symptoms (absent or present), anatomic location (maxilla or mandible), epithelial thickness (atrophic or hyperplastic), satellite cysts (absent or present), cystic spaces (absent or present), inflammatory infiltrate (absent or present), locularity (unilocular or multilocular), lesion borders (well defined or poorly defined), previous decompression (yes or no), recurrence (yes or no), time to recurrence, and time of follow-up. The epithelial lining of OKC was classified according to thickness as atrophic (5–8 cell layers) or hyperplastic (more than 8 cell layers) [9].

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate the associations of the variables with recurrence, with p ≤ 0.05 indicating statistically significant associations. The McNemar test for paired data was used to compare the variables between primary and recurrent OKC lesions. Recurrence-free survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and the survival functions were compared according to the variables by the log-rank test.

Results

In the cohort analyzed, 18 (45%) cases were recurrent OKCs and 22 (55%) were non-recurrent OKCs. There was a predominance of OKC among females (n = 23) compared to males (n = 17), with a female-to-male ratio of 1.3:1. The mean age at diagnosis was 34.7 ± 16.7 years and most patients were white (n = 18, 45.0%). The posterior mandible was the most affected site in the population studied (n = 31, 77.5%), followed by the anterior mandible (n = 4, 10.0%), posterior maxilla (n = 4, 10.0%), and anterior maxilla (n = 1, 2.5%).

Comparison of the clinicopathological variables between primary and recurrent OKC lesions revealed no differences in the frequency of atrophic and hyperplastic epithelium, presence of satellite cysts and cystic spaces (p = 1.000), or presence of an inflammatory infiltrate (p = 0.625). The imaging findings such as locularity (p = 0.727) and lesion borders (p = 0.687) were also similar (Table 1).

Atrophic epithelium was the most frequent type found in both groups of recurrent and non-recurrent lesions, showing no significant association (p = 0.435). Satellite cysts were more frequent in the group of recurrent lesions and showed a significant association (p = 0.002). The presence of an inflammatory infiltrate was also significantly associated with recurrent lesions (p = 0.006) (Table 1).

The frequency of painful symptoms was practically the same even after recurrence (p = 0.727). Frequency of symptoms was the same in all selected cases, with the patients commonly reporting some discomfort (n = 11). This parameter was not significantly associated with recurrence (p = 1.000). Regarding the therapeutic approach, decompression or marsupialization was more commonly used in recurrent lesions (n = 6) and was significantly associated with recurrence (p = 0.047).

Primary lesions had a mean size of 2.2 ± 1.1 cm and recurrent lesions of 3.0 ± 2.0 cm, i.e., there were more cases of recurrent lesions larger than 2 cm than primary lesions (p = 0.146). Non-recurrent lesions had a mean size of 3.2 ± 2.1 cm, i.e., in 13 cases the lesion was larger than 2 cm. However, lesion size was not significantly associated with the presence of recurrence (p = 0.152) (Table 1).

With respect to the imaging findings, multilocular lesions were more frequently observed in non-recurrent cases, but this feature was not significantly associated with recurrence (p = 0.131). The lesion border was well delimited in most lesions, with two cases of irregular margins in non-recurrent OKC and three cases in recurrent OKC; however, this parameter was not significantly associated with recurrence (p = 0.650).

The treatment modalities for primary lesions were enucleation combined with curettage and/or Carnoy’s solution (n = 12) and ostectomy combined with Carnoy’s solution (n = 6). Treatment of recurrent lesions included ostectomy combined with Carnoy’s solution (n = 12), enucleation combined with curettage and/or Carnoy’s solution (n = 5), and resection and bone graft placement (n = 1). On the other hand, non-recurrent lesions were treated as follows: previous decompression or marsupialization (n = 1), enucleation combined with curettage and/or Carnoy’s solution (n = 12) and ostectomy combined with Carnoy’s solution (n = 9).

The median recurrence-free survival at 5 years was 6.0 (3.0–24.0) months. The highest survival was observed in cases without satellite cysts (67.39%; 95% CI 46.52–81.58) or inflammatory infiltrate (79.44%; 95% CI 48.79–92.89) and no previous decompression or marsupialization (59.99%; 95% CI 40.26–75.05). The mean time of follow-up was 81.32 ± 64.88 months (range: 9 to 295 months). At the end of the study, there were two losses to follow-up over 5 years, as shown in Table 2 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of recurrence-free survival according to clinical and imaging variables of OKCs. a Presence of symptoms. b Locularity (unilocular or multilocular). c Radiographic borders (well defined or poorly defined). d Size (≤ 2 or > 2 cm). e Initial conservative treatment (decompression or marsupialization). The log-rank test showed a statistically significant association only for previous decompression or marsupialization (p = 0.010)

Kaplan–Meier curves of the relationship between morphological findings and recurrence-free survival in OKCs. a Epithelial thickness. b Presence of satellite cysts. c Presence of multiple cystic spaces. d Presence of inflammatory infiltrate. The log-rank test revealed statistically significant associations only for satellite cysts and inflammatory infiltrate

Discussion

The present study permitted to identify the main characteristics of patients with OKC seen at a referral center for oral-maxillofacial surgery and traumatology in northeastern Brazil. In addition, the main associated prognostic factors were identified. In the present study, OKCs occurred in patients across a wide age range, with a mean age of 34.7 years, in agreement with the literature which indicates that this lesion commonly affects adults in the fourth decade of life [7, 10]. In contrast to other studies [6,7,8, 11, 12], most of the patients analyzed herein were women. The posterior mandible was the most affected site, in agreement with the literature [7, 13, 14].

OKCs are characterized by a high recurrence rate after treatment [1, 13,14,15]. Different factors can explain this high rate, including the size of the lesion, association with Gorlin syndrome, different treatment methods, and anatomic location [1, 7, 15, 16]. In the present study, non-recurrent lesions had a larger mean size. This finding can be explained by the fact that surgeons in the aforementioned service often choose more aggressive treatment after decompression in the case of larger lesions aiming to prevent recurrences. In addition, OKCs located in the mandible seem to be associated with the development of future recurrence, as evidenced in the studied sample.

Histological findings can be associated with the recurrence of OKC [17]. We analyzed some histopathological features and found no significant association between recurrence of OKC and epithelial thickness or presence of cystic spaces. However, there was a significant association of the presence/absence of satellite cysts and inflammatory infiltrate with recurrence of OKC. No differences in the histopathological features were observed between primary and recurrent lesions.

The presence of dental lamina remnants adjacent to satellite cysts is one reason to explain the high tendency for recurrence associated with cell proliferation in the cystic capsule. Suprabasal mitoses in the epithelial lining, presence of proliferating odontogenic epithelium in the capsule and satellite cysts in the wall of OKC are significantly more common in syndromic multiple OKCs than in solitary cases. These characteristics are indicators of a higher proliferative capacity in syndromic OKCs and in recurrent cases [5].

Satellite cysts usually take three forms: (1) keratin-filled cysts lined by cuboidal cells; (2) squamous structures with central degeneration occupied by epithelial debris; and (3) small irregular shaped cysts of which lining is indistinguishable from that of the main cyst. The first two are more frequently found in solitary cases (Fig. 3). It is often postulated that basal cell budding may be important for the formation of satellite cysts in syndromic OKCs [5]. According to Bello et al. [5], recurrences may be attributed to the proliferative activity of satellite cysts formed as a result of basal cell budding in the epithelium and their detachment in connective tissue and subsequent cystification. However, histological evidence favors the development of satellite cysts from the proliferation of epithelial rests of Serres in cases of sporadic OKC [18].

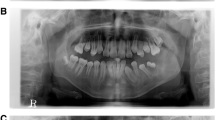

Recurrent OKC. a Classical features of OKC. Parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium showing a hyperchromatic and polarized basal cell layer and flat epithelial-connective tissue interface. Note budding of basal cells (arrows). b Detachment of portions of the epithelium from the fibrous capsule is usually seen. c Presence of a satellite cyst in the capsule, characterized by a round, keratin-filled cyst lined by cuboidal cells. d Inflammation of the epithelial lining and hyperplasia. Connective tissue is densely infiltrated with chronic inflammatory cells (× 200)

According to Pereira et al. [19] and Lira et al. [20], the degree of inflammation in OKC is low. In the studied sample, the presence of inflammatory infiltrate was found in some cases of primary and recurrent OKC (Fig. 3), and showed a significant association with a reduction in recurrence-free survival. Thus, our findings suggest that inflammation predisposes to recurrences in OKC. This hypothesis can be supported by the fact that a high degree of inflammation increases epithelial thickness. In addition, inflammatory cells can secrete growth factors that stimulate the proliferation of epithelial lining cells [21]. Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that alterations in oxygen levels caused by inflammatory conditions influence the biology of neoplastic cells. In odontogenic lesions, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is considered a marker of hypoxia and has been associated with invasiveness and cystic formation. Overexpression of this transcription factor has been reported in OKCs [22].

OKCs can vary between uni- and multilocular radiographic appearance, with a predominance of unilocular lesions [8, 10, 11, 13, 14]. We found some interesting associations between the radiologic findings and recurrence of OKC. Multilocularity was the most common radiographic appearance in both recurrent and non-recurrent groups. However, in the recurrent group, a unilocular radiographic appearance was the most common finding in primary lesions. Despite this prevalence, no significant relationship was found, as also previously reported [23]. Kinard et al. [8] reported a higher prevalence of unilocular lesions but the risk of recurrence was 4.7-fold higher in multilocular lesions. In our study, most OKCs had well-defined borders. It is worth mentioning that computed tomography allows to evaluate cortical bone perforation, which is common and is associated with the recurrence of OKC [8, 10].

Symptoms associated with OKC are an uncommon clinical finding and, if present, do not account for more than 50% of cases [11, 12, 24, 25]. However, in a 10-year retrospective study, Habibi et al. [26] found symptoms in 75.9% of their sample. In our study, the presence of symptoms was uncommon and was not significantly associated with recurrence; however, if symptoms were present, they were mostly observed in recurrent cases. The main associated symptoms include swelling, pain, purulent secretion, and paresthesia [3, 11, 12, 25, 26].

In our study, the recurrence rate was 45% and the time to relapse ranged from 2 to 60 months after the surgical procedure. Kinard et al. [10] reported a recurrence rate of 19% in a multicenter study of 231 patients followed up over a period of 12 years. Cunha et al. [7], studying 24 patients submitted to standard surgery (i.e., decompression and enucleation) and followed up over a period of 10 years, found a recurrence rate of 33%. Although there are several accepted therapies for OKC, no consensus exists in the literature. Treatment options include conservative methods, such as enucleation (with or without curettage), decompression and marsupialization, in addition to aggressive approaches that include peripheral ostectomy, cryotherapy, application of Carnoy’s solution, and resection of the mandible. All of these techniques aim to remove the cyst and to reduce the risk of recurrence [1, 6, 8, 11, 16, 27,28,29].

A wide range of treatment modalities was found in the present study, with conservative treatments being preferably performed on primary lesions. Marsupialization and decompression are conservative techniques for the treatment of OKC, which are followed by removal of the lesion [15, 16, 29]. In our study, recurrent cases showed a significant association with marsupialization or decompression (prior to surgical excision). Our data agree with the literature suggesting that marsupialization/decompression is associated with higher recurrence of OKC [8, 10, 14,15,16, 28,29,30].

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the prognostic factors involved with recurrences of OKC are the presence of satellite cysts, inflammatory infiltrate and the previous performance of decompression or marsupialization that modify peculiarities of the epithelium. Histological characteristics of OKC play a minor role but should not be neglected, and a better understanding is necessary. In our study, the most significant morphological parameters associated with recurrences were the presence of satellite cysts and inflammatory infiltrate. If the cyst and its content are completely removed, the risk of recurrence is low but continues due to the particularities of epithelial proliferation in OKC.

References

Vallejo-Rosero KA, Camolesi GV, de Sá PLD et al (2019) Conservative management of odontogenic keratocyst with long-term 5-year follow-up: case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 20(66):8–15

Doll C, Dauter K, Jöhrens K et al (2018) Clinical characteristics and immunohistochemical analysis of p53, Ki-67 and cyclin D1 in 80 odontogenic keratocysts. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 119(5):359–364

Santosh ABR (2020) Odontogenic cysts. Dent Clin N Am 64(1):105–119

Polak K, Jędrusik-Pawłowska M, Drozdzowska B et al (2019) Odontogenic keratocyst of the mandible: a case report and literature review. Dent Med Probl 56(4):443–536

Bello IO (2016) Keratocystic odontogenic tumor: a biopsy service’s experience with 104 solitary, multiple and recurrent lesions. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2(5):538–546

Sigua-Rodriguez EA, Goulart DR, Sverzut A et al (2019) Is surgical treatment based on a 1-step or 2-step protocol effective in managing the odontogenic keratocyst? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 77(6):1210.e1–1210.e7

Cunha JF, Gomes CC, de Mesquita RA et al (2016) Clinicopathological features associated with the recurrence of odontogenic keratocyst: a cohort retrospective analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 121(6):629–635

Kinard BE, Chuang SK, August M et al (2013) How well do we manage the odontogenic keratocyst? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 71(8):1353–1358

Telles DC, Castro WH, Gomez RS et al (2013) Morphometric evaluation of keratocystic odontogenic tumor before and after marsupialization. Braz oral res 27(6):496–502

Kinard B, Hansen G, Newman M et al (2019) How well do we manage the odontogenic keratocyst? A multicenter study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 127(4):282–288

Pitak-Arnnop P, Chaine A, Oprean N et al (2010) Management of odontogenic keratocysts of the jaws: a ten-year experience with 120 consecutive lesions. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 38(5):358–364

Boffano P, Ruga E, Gallesio C (2010) Keratocystic odontogenic tumor (odontogenic keratocyst): preliminary retrospective review of epidemiologic, clinical, and radiologic features of 261 lesions from University of Turin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68(12):2994–2999

Borghesi A, Nardi C, Giannitto C et al (2018) Odontogenic keratocyst: imaging features of a benign lesion with an aggressive behaviour. Insights Imaging 9(5):883–897

de Castro MS, Caixeta CA, de Carli ML et al (2018) Conservative surgical treatments for nonsyndromic odontogenic keratocysts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 22(5):2089–2101

Mendes RA, Carvalho JF, van der Waal I (2010) Characterization and management of the keratocystic odontogenic tumor in relation to its histopathological and biological features. Oral Oncol 46(4):219–225

Kaczmarzyk T, Mojsa I, Stypulkowska J (2012) A systematic review of the recurrence rate for keratocystic odontogenic tumour in relation to treatment modalities. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41(6):756–767

Cottom HE, Bshena FI, Speight PM et al (2012) Histopathological features that predict the recurrence of odontogenic keratocysts. J Oral Pathol Med 41(5):408–414

Wright JM, Odell EW, Speight PM et al (2014) Odontogenic tumors, WHO 2005: where do we go from here? Head Neck Pathol 8(4):373–382

Pereira CCS, Carvalho ACGS, Gaetti-Jardim EC et al (2012) Tumor odontogênico queratocístico e considerações diagnósticas. Revista Brasileira de Ciências da Saúde 10(32):73–79

Lira AAB, Cunha BB, Brito HBS et al (2010) Tumor odontogênico ceratocístico. Revista Sul Brasileira de Odontologia 7(1):95–99

Chang CH, Wu YC, Wu YH et al (2017) Significant association of inflammation grade with the number of Langerhans cells in odontogenic keratocysts. J Formos Med Assoc 116(10):798–805

Costa NMM, Abe CTS, Mitre GP et al (2019) HIF-1α is overexpressed in odontogenic keratocyst suggesting activation of hif-1α and notch1 signaling pathways. Cells 8(7):1–13

Leung YY, Lau SL, Tsoi KYY et al (2016) Results of the treatment of keratocystic odontogenic tumours using enucleation and treatment of the residual bony defect with Carnoy’s solution. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 45(9):1154–1158

Simiyu BN, Butt F, Dimba EA et al (2013) Keratocystic odontogenic tumours of the jaws and associated pathologies: a 10-year clinicopathologic audit in a referral teaching hospital in Kenya. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 41(3):230–234

Morgan TA, Burton CC, Qian F (2005) A retrospective review of treatment of the odontogenic keratocyst. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 63(5):635–639

Habibi A, Saghravanian N, Habibi M et al (2007) Keratocystic odontogenic tumor: a 10-year retrospective study of 83 cases in an Iranian population. J Oral Sci 49(3):229–235

Zecha JA, Mendes RA, Lindeboom VB et al (2010) Recurrence rate of keratocystic odontogenic tumor after conservative surgical treatment without adjunctive therapies—a 35-year single institution experience. Oral Oncol 46(1):740–742

Kolokythas A, Fernandes RP, Pazoki A et al (2007) Odontogenic keratocyst: to decompress or not to decompress? A comparative study of decompression and enucleation versus resection/peripheral ostectomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65(4):640–644

Tabrizi R, Hosseini Kordkheili MR, Jafarian M et al (2019) Decompression or marsupialization; Which conservative treatment is associated with low recurrence rate in keratocystic odontogenic tumors? A systematic review. J Dent Shiraz Univ Med Sci 20(3):145–151

Al-Moraissi EA, Dahan AA, Alwadeai MS et al (2017) What surgical treatment has the lowest recurrence rate following the management of keratocystic odontogenic tumor?: a large systematic review and meta-analysis. Craniomaxillofac Surg 45(1):131–144

Acknowledgements

We thank the Pathological Anatomy Service of the Discipline of Oral Pathology, Department of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, for providing the material and laboratory resources necessary for the study.

Funding

The authors thank the Department of Dentistry, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brazil for its support. Funding was provided by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior [Grant no. 001].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GMF—collection, data analysis and article writing. LBAS—collection, data analysis and article writing. RPM—collection, data analysis and article writing. WRS—collection, data analysis and article writing. KCL—statistical analysis. HCG—guidelines and corrections for the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de França, G.M., da Silva, L.B.A., Mafra, R.P. et al. Recurrence-free survival and prognostic factors of odontogenic keratocyst: a single-center retrospective cohort. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 278, 1223–1231 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06229-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06229-8