Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effects of the combination of pelvic floor rehabilitation, intravaginal estriol and Lactobacillus acidophli administration on stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urogenital atrophy and recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women.

Methods

136 postmenopausal women with urogenital aging symptoms were enrolled in this prospective randomized study. Patients: randomly divided into two groups and each group consisted of 68 women. Interventions: Subjects in the triple therapy (group I) received 1 intravaginal ovule containing 30 mcg estriol and Lactobacilli acidophili (50 mg lyophilisate containing at least 100 million live bacteria) such as once daily for 2 weeks and then two ovules once weekly for a total of 6 months as maintenance therapy plus pelvic floor rehabilitation. Subjects in the group II received one intravaginal estriol ovule (1 mg) plus pelvic floor rehabilitation in a similar regimen. Mean outcome measures: We evaluated urogenital symptomatology, urine cultures, colposcopic findings, urethral cytologic findings, urethral pressure profiles and urethrocystometry before, as well as after 6 months of treatment.

Results

After therapy, the symptoms and signs of urogenital atrophy significantly improved in both groups. 45/59 (76.27 %) of the group I and 26/63 (41.27 %) of the group II referred a subjective improvement of their incontinence. In the patients treated by triple therapy with lactobacilli, estriol plus pelvic floor rehabilitation, we observed significant improvements of colposcopic findings, and there were statistically significant increases in mean maximum urethral pressure, in mean urethral closure pressure, as well as in the abdominal pressure transmission ratio to the proximal urethra.

Conclusions

Our results showed that triple therapy with L. acidophili, estriol plus pelvic floor rehabilitation was effective and should be considered as first-line treatment for symptoms of urogenital aging in postmenopausal women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Symptoms and signs of urogenital integrity disorders involving the lower urinary tract, genital tract and pelvic floor become evident after menopause increasing with advancing age [1, 2].

In the West, 8–30 % of the total population has urogenital problems [3].

The symptoms relating to urogenital aging may be categorized into two groups: those localized to the lower urinary tract (urethra and bladder) and those confined to the vagina and vulva. The first group includes frequency and urgency, nocturia, dysuria, recurrent urinary tract infections and urinary incontinence; the second group comprises vaginal dryness, itching, burning and dyspareunia.

It is now well demonstrated that the urogenital organs are highly sensitive to the influence of estrogen. In fact, estrogen receptors have been found in the urethra and bladder trigone [4], as well as in the round ligaments and levator ani muscles [5].

In the vagina, the progressive decline of estrogens during climacterium induces an atrophy of the mucosa, which becomes thinner.

Similarly in the urethra and bladder the reduction of estrogens produces the atrophy of the mucosae, causing nocturia, dysuria and urinary urgency.

Lactobacilli species are the predominant microbiota of the vagina and contribute to innate host defense. Several studies [6–8] have focused on the antimicrobial activity of hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid, and bacteriocins as mediators of the antimicrobial activity of lactobacilli.

Estrogen stimulates the proliferation of lactobacillus in the vaginal epithelium, reduces pH, and avoids vaginal colonization of Enterobacteriaceae, which are the main pathogens of the urinary tract infections (UTI) [9].

In postmenopausal women who are prone to UTI, because of estrogen deficiency, one non-antimicrobial adjunct treatment approach for which there is strong mechanistic evidence is use of a hydrogen peroxide-producing (H2O2 +) lactobacillus probiotic to restore the normal vaginal microbiota [10].

The efficacy of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) on urogenital complaints has already been clearly demonstrated by numerous clinical studies [11–15].

Estriol is considered to be free of the potential risks associated with the systemic use of estrogenic therapy [16], moreover it has been definitively demonstrated that intravaginal estriol does not stimulate the proliferation of endometrium [17]. Its vaginal absorption is swift and effective, and bypasses the first hepatic inactivation and more stable circulating levels are achieved with respect to the oral route.

Several studies [17–24] have shown the efficacy of intravaginal estriol in the treatment of urogenital atrophy, of recurrent urinary tract infections [25, 26] and of climacteric symptoms [19, 22].

We have already demonstrated the efficacy and safety of intravaginal estriol administration on urinary incontinence, urogenital atrophy and recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women [15].

Recently, we have reported that combination therapy with estriol plus pelvic floor rehabilitation was effective for treatment of symptoms of urogenital aging in postmenopausal women [27].

Several conservative treatment options are available for the management of stress urinary incontinence (SUI), e.g., physical therapies, behavioral modification, and pharmacological intervention [28]. Pelvic floor rehabilitation is prescribed as first-line treatment for women with SUI, particularly in cases of urinary incontinence with poor-quality perineal testing results or inverted perineal command [29–31].

The aim of our study was to investigate the effects of the triple therapy consisting of combination of pelvic floor rehabilitation (pelvic floor muscle training and electrical stimulation) and L. acidophili plus intravaginal estriol on urinary incontinence, urogenital atrophy and recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was carried out from May 2010 to March 2012 in Sassari, the largest district of northern Sardinia with 130,366 inhabitants and a density of 239.3 inhabitants/km2. The populations included 14,273 women of age range 55–70 years old.

Sampling

Sample size was calculated on the basis of prevalence of urinary incontinence, urogenital atrophy and recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women, increased by 10 %. Consequently, our estimates were safeguarded at an optimal level of precision (5 %) against the possible effect of (1) disease reduction since the previous study and (2) the non-response numbers.

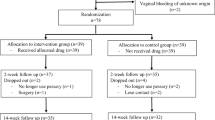

The theoretical sample size was 357. All the women were issued with an information leaflet explaining the aim of the study and requesting their participation. Eighty-one (22.69 %) women chose not to participate, hence, 276 (77.31 %) women were evaluated (Fig. 1)..

An initial assessment (screening visit or visit 1) including the recent history of somatic symptoms, complete medical and surgical history, and a complete physical and gynecological examination was performed to determine the subject’s suitability for the study in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria.

If the subject was suitable for the study an appointment was made for her to return for the baseline visit (visit 2). During the baseline visit the determination of vaginal pH, colposcopic examination, vaginal and urethral smears, urodynamic examination, and a further check of compliance of subject with inclusion and exclusion criteria were performed (Fig. 1).

All patients presented symptoms and signs of urinary stress incontinence, vaginal atrophy, and histories of recurrent urinary tract infections. None of the patients had received estrogen treatment prior to the study. The patients with previous hysterectomy were eligible for the study too.

Exclusion criteria for the study were pathologies or anatomical lesions of the urogenital tract such as uterovaginal prolapse, cystocele, and rectocele of grade II or III according to Baden and Walker classification (HWS), presence of severe systemic disorders, thromboembolic diseases, biliary lithiasis, previous breast or uterine cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding and body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2.

The diagnosis of genuine stress urinary incontinence was confirmed by the direct visualization of loss of urine from the urethra during the standard stress test and by urodynamic investigation. Patients with detrusor overactivity and abnormal maximal cystometric capacity were excluded from the study.

Hence, the study reports data on 136 postmenopausal women with urogenital aging symptoms. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the screened patients.

At this point the eligible women signed informed consent and were randomly assigned into two groups (I and II). Each group consisted of 68 women. Randomization was obtained using sets of sequenced, sealed, opaque envelopes, each containing the bottle number to be given to each patient.

Subjects in the group I were given intravaginal ovules: one ovule containing L. acidophili (50 mg lyophilisate with at least 100 million live bacteria) and estriol (30 mcg) once daily for 2 weeks (Donaflor, Bruno Farmaceutici, Rome, Italy) and then two ovules once weekly as maintenance therapy for a total of 6 months plus pelvic floor muscle training group and electrical stimulation.

Subjects in the group II were given intravaginal estriol ovules: one ovule (1 mg) once daily for 2 weeks (Colpogyn, Angelini, Rome, Italy) and then two ovules once weekly as maintenance therapy for a total of 6 months plus pelvic floor muscle training group and electrical stimulation.

Pelvic floor muscle training and electrical stimulation were performed as explained by Castro et al. [30].

We did not use a placebo group because all the women enrolled had urogenital atrophy requiring local estrogen therapy. Recently, Archer [32] showed the efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. We have already demonstrated the advantage of estriol vs. placebo [15].

We evaluated the urogenital symptomatology, urine cultures, colposcopic findings, urethral cytologic findings, urethral pressure profile, and urethrocystometry before, as well as after 6 months of treatment.

The women enrolled in the study complained of the main symptoms of stress urinary incontinence, such as urine loss with physical exertion, coughing, sneezing and intercourse, and symptoms of genital atrophic conditions, including vaginal dryness and dyspareunia.

The subjective evaluation of incontinence disorders was based on the patient’s description regarding the effect of the incontinence with respect to activities at home and at work (incontinence impact questionnaire) [33]. The urinary incontinence complaints were assessed as: none, mild, moderate, severe.

The therapy efficacy on urinary incontinence complaints was assessed as follows: women who changed from ‘mild/moderate/severe’ to ‘none’ were classified as ‘cured’. Women who changed from ‘moderate’ to ‘mild’ or from ‘severe’ to ‘moderate/mild’ were classified as ‘improved’. Women who did not change from pretreatment were classified as ‘no change’. Women who changed from ‘none’ to ‘mild/moderate/severe’ or from ‘mild’ to ‘moderate/severe’ or from ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’ were classified as ‘worse’.

The symptoms relating to urogenital atrophy such as vaginal dryness and dyspareunia were classified as follows: none, moderate or severe at each visit. Therapy efficacy on atrophic condition complaints was assessed as described above.

The gynecological evaluation included vaginal atrophy and pH assessment.

The authors visually assessed the degree of urogenital atrophic conditions as none, moderate or severe at each visit, taking into account pallor, petechiae, friability and vaginal dryness (no, yes) as objective evidence of estrogen deficiency.

Vaginal pH was measured using an indicator strip, and midstream urine specimens were obtained at the beginning of the study and after 6 months of treatment.

Significant bacteriuria was considered to be present if the midstream urine culture yielded ≥105 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter.

The decrease in thickness of pavement epithelium of portio was subjectively assessed as present or absent.

We performed Schiller’s test in all patients and visually evaluated the possible presence of petechiae.

Vaginal and urethral smears were taken during colposcopic examination by the cytobrush sampling technique from the upper lateral vaginal walls and from the distal urethral walls. After preparation with a cytology fixative, the smears were sent to the pathologist for preparation and staining according to Papanicolaou.

The effect of estriol on the vaginal and urethral epithelium was estimated by means of the karyopyknotic index (KPI), defined as the percentage of superficial cells found in the total population of the squamous cells examined [34], which is considered a reliable cellular index for the determination of estrogen activity [35].

We calculated the urethral pressure profile and urethrocystometry at the beginning of the study and after 6 months of treatment according the criteria of the International Continence Society (ICS), using the Phoenix Plus videourodynamic machine (Albyn Medical LTD, Dingwall, Scotland).

Urethral and intravesical pressures were measured in the supine position by a catheter equipped with a microtransducer two-way standard (Albyn Medical LTD, Dingwall, Scotland). Vesical filling was performed with saline solution at a constant speed of 50 ml/min. By three reproducible urethral pressure profiles, the mean maximum urethral pressure (MUP) and the mean maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP) were calculated. The abdominal pressure transmission ratio (PTR) to the urethra was calculated as a/b × 100 where a is the urethral pressure increase and b is the intravesical pressure increase during coughing.

At the beginning of the study, the women received a diary in which they were asked to record the occurrence of localized or systemic side effects. Six months later we reviewed these diaries to assess the treatment compliance.

Our Ethic Board Committee approved the study.

Statistical analysis

It is a common feature to have drop-out patients in studies designed such as our. Nevertheless, we decided to include the eventual drop-out patients in statistical analysis.

In the statistical elaboration of the data concerning the drop-outs, the unavailable outcome data were assumed to be worst case, i.e., the parameters taken into account at the baseline were considered to have remained unchanged.

All the data were computed in a database. The analysis was carried out using an Anova one way for means observation and χ 2 with collinearity for dichotomous variables. All statistical significance figures apply to the after-treatment measurements.

Results

The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The I and II groups were homogenous for age, vaginal parity, menopause duration, and duration of urinary incontinence.

Before starting therapy, 59/68 patients in group I versus 63/68 patients in group II presented symptoms of stress incontinence ranging from mild to moderate.

After 6 months, 45/59 (76.27 %) of the treated patients with triple therapy referred subjective improvement of their incontinence (31 totally continent and 14 significantly improved), while only 26/63 (41.27 %) of the group II reported this improvement (P < 0.01) (Table 2).

Before starting therapy, all the 136 patients had presented urogenital atrophy ranging from moderate to severe and had suffered from vaginal dryness; 43 in the group I and 39 in the group II referred symptoms of dyspareunia.

Subsequently, on clinical examination symptoms and signs of urogenital atrophy, vaginal dryness, and dyspareunia improved significantly in the group I in comparison to the group II (Table 2).

At baseline, 19 women (27.94 %) had presented significant bacteriuria (Escherichia coli in all cases) in the group I and 16 (23.53 %) in the group II (E. Coli and/or streptococcus in all cases). After the treatment, there was a significant quantity of bacteria in the urine of 6/19 patients (31.58 %) and in 9/16 (56.25 %), respectively (P < 0.001).

The mean vaginal pH at baseline was 5.63 ± 0.76 for the group I and 5.53 ± 0.64 for the group II. After therapy, vaginal pH was 4.24 ± 0.66 and 4.78 ± 0.71, respectively (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

In both groups, a statistically significant improvement of colposcopic parameters and a significant rise in KPI were found after treatment in the vaginal and urethral epithelium (Table 3).

In both groups (I and II), a statistically significant increase in mean MUP and MUCP and a significant increase in mean PTR were found after treatment (Table 4).

Urethrocystometry showed positive modifications in the both groups which were not, however, statistically significant (Table 5).

No systemic adverse reactions were observed.

We did not observe drop-out patients.

Discussion

A meta-analysis on 77 studies [2] has shown estrogens (administered orally or vaginally, and in all dosage regimens) to be efficacious in the treatment of urogenital atrophy. In particular, the local low-dose estrogen therapy (using both estradiol and estriol) is as effective as systemic estrogen therapy in the treatment of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women.

The effectiveness of estriol on the vaginal epithelium and urethra is well documented [17, 20].

We have already demonstrated that intravaginal estriol therapy was effective in the treatment of symptoms and signs of urogenital aging [15].

Recently, we have reported that combination therapy with estriol plus pelvic floor rehabilitation was effective for the treatment of symptoms of urogenital aging in postmenopausal women [27].

Physical therapies involving pelvic floor muscle training with or without other treatments such as vaginal cones, biofeedback, and electrical stimulation are the standard for conservative treatment and prevention of SUI [28, 29]. Castro et al. [30] in a randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial, compared the effectiveness of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active treatment in women with urodynamic stress urinary incontinence and demonstrated that these modalities are equally effective treatments and are far superior to no treatment in women with urodynamic SUI.

Pelvic floor rehabilitation is prescribed as first-line treatment for women with SUI, particularly in cases with poor-quality perineal testing results or inverted perineal command [31].

Ishiko et al. [33] investigated the effects of the combination of pelvic floor exercise and estriol on postmenopausal SUI by a randomized study (pelvic rehabilitation and estriol versus only rehabilitation): the authors demonstrated the efficacy of the combination therapy.

Recurrent urinary tract infections represent a serious complaint for many postmenopausal women. In the menopause period, the reduction of lactobacillus colonization, vaginal pH reduction and the atrophy of the vaginal mucosa are involved in the higher frequency of urinary tract infections. The use of intravaginal estriol and L. acidophili for 6 months determined a significant reduction in the number of cases of bacteriuria and a decrease of vaginal pH.

The effectiveness of local estriol administration for the treatment of urogenital symptoms has been well documented by several authors [11–15].

Schar et al. [34] suggest estriol local therapy as an effective mode of primary treatment in postmenopausal women with urinary incontinence.

In a multicenter study on 251 postmenopausal women, Lose et al. [35] showed that the vaginal administration of low-dose estradiol and estriol is equally efficacious in alleviating lower urinary tract symptoms which appear after the menopause.

Iosif [18] in a longitudinal study reported that 75 % of the women referred significant subjective improvement of stress incontinence, and a significant increase in pressure transmission ratio to the proximal urethra was noted after vaginal medication with estriol.

We have already demonstrated that the patients treated by vaginal estriol referred, on clinical examination, an improvement of their incontinence after local estrogenic therapy. Statistically significant increases were noted in urodynamic parameters such as MUP, MUCP, and PTR in comparison to the control subjects [15].

According to several authors, estrogen therapy relieves the symptoms of stress incontinence by causing proliferation and growth of the urethral mucosa and blood vessel engorgement, which in turn constitute the “urethral softness factor” [18].

According to Bathia [36], the significant increase of abdominal pressure transmission to the proximal third of the urethra is to be considered a positive clinical response. This crucial effect is probably due to extraurethral factors such as improved functioning of the pelvic floor muscles [37]. In summary, increased tissue tension and urethral pressure along with improved pressure transmission to the proximal urethra play an important role in the alleviation of genuine stress incontinence.

With regard to the risks of local estrogen therapy, estriol is considered to be free from potential adverse reactions of systemic estrogenic therapy [18]. Intravaginal estriol does not stimulate the proliferation of endometrium [17]. Furthermore, local treatment of vaginal atrophy is not associated with possible risks of systemic HRT such as breast cancer [38].

Iosif [18] recovered endometrial biopsies from 48 patients after 8–10 years of therapy with estriol suppositories and seven showed weak proliferative changes, thus demonstrating that the risk of adverse reactions to estriol is insignificant.

In our series, the compliance of the tested patients was high and all completed the study. We did not observe adverse drug systemic effects.

Recently, Jaisamrarn et al. [39], in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, concluded that the ultra-low-dose, vaginal 0.03 mg estriol-lactobacilli combination was superior to placebo with respect to changes in vaginal maturation index (VMI) after the 12-day initial therapy, and the maintenance therapy of two tablets weekly was sufficient to prevent the relapse of vaginal atrophy. The results of this study [39] are in agreement with our results that demonstrated a sinergical effect of estriol-lactobacilli combination plus pelvic floor rehabilitation on treatment of symptoms of urogenital aging such as mild urinary incontinence and urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women. In fact, this effect was statistically better with addition of lactobacilli in (subjective) incontinence (not in urethrocystometry), vaginal pH, atrophy and bacteriuria.

In conclusion, triple therapy with L. acidophili, estriol and rehabilitation (muscle exercise and electrostimulation) was highly efficacious in reducing the urogenital atrophy and frequency of urinary tract infections, as well as the symptoms and signs of stress urinary incontinence; furthermore this treatment was seen to be safe and well-tolerated by the patients.

Indeed, we think that triple therapy should be considered the first-line treatment for mild SUI in postmenopausal women.

References

Singh S, van Herwijnen I, Phillips C (2013) The management of lower urogenital changes in the menopause. Menopause Int 19:77–81

Cardozo L, Bachmann G, McClish D, Fonda D, Birgenson L (1998) Meta-analysis of estrogen therapy in the management of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women: second report of the hormones and urogenital therapy committee. Obstet Gynecol 92:722–727

Legendre G, Ringa V, Fauconnier A, Fritel X (2013) Menopause, hormone treatment and urinary incontinence at midlife. Maturitas 74:26–30

Iosif CS, Batra S, Ek A, Astedt B (1981) Estrogen receptors in the human female lower urinary tract. Am J Obstet Gynecol 141:817–820

Smith P (1993) Estrogens and the urogenital tract. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 157(suppl):1–25

Cadieux PA, Burton J, Devillard E, Reid G (2009) Lactobacillus by-products inhibit the growth and virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Physiol Pharmacol 60(Suppl 6):13–18

Atassi F, Servin AL (2010) Individual and co-operative roles of lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide in the killing activity of enteric strain Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC933 and vaginal strain Lactobacillus gasseri KS120.1 against enteric, uropathogenic and vaginosis-associated pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Lett 304:29–38

Antonio MA, Hillier SL (2003) DNA fingerprinting of Lactobacillus crispatus strain CTV-05 by repetitive element sequence-based PCR analysis in a pilot study of vaginal colonization. J Clin Microbiol 41:1881–1887

Raz R (2011) Urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Korean J Urol 52:801–808

Stapleton AE, Au-Yeung M, Hooton TM, Fredricks DN, Roberts PL, Czaja CA, Yarova-Yarovaia Y, Fiedler T, Cox M, Stamm WE (2011) Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of a Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis 52:1212–1217

Samsioe G, Jansson I, Mellstrom D, Svanborg A (1985) Occurrence, nature and treatment of urinary incontinence in a 70-year-old female population. Maturitas 7:335–342

Nilsson K, Heimer G (1992) Low-dose oestradiol in the treatment of urogenital oestrogen deficiency: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Maturitas 15:121–127

Smith P, Heimer G, Lindskog M, Ulmsten U (1993) Oestradiol-releasing vaginal ring for treatment of postmenopausal urogenital atrophy. Maturitas 16:145–154

Fantl JA, Cardozo L, McClish DK (1994) Estrogen therapy in the management of urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis. First report of the hormones and urogenital therapy committee. Obstet Gynecol 83:12–18

Dessole S, Rubattu G, Ambrosini G, Gallo O, Capobianco G, Cherchi PL, Marci R, Cosmi E (2004) Efficacy of low-dose intravaginal estriol on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Menopause 11:49–56

Esposito G (1991) Estriol: a weak estrogen or a different hormone? Gynecol Endocrinol 5:131–153

Heimer GM, Englund DE (1992) Effects of vaginally-administered oestriol on post-menopausal urogenital disorders: a cytohormonal study. Maturitas 14:171–179

Iosif CS (1992) Effects of protracted administration of estriol on the lower genito urinary tract in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 251:115–120

Foidart JM, Vervliet J, Buytaert P (1991) Efficacy of sustained-release vaginal oestriol in alleviating urogenital and systemic climacteric complaints. Maturitas 13:99–107

Van der Linden MC, Gerretsen G, Brandhorst MS, Ooms EC, Kremer CM, Doesburg WH (1993) The effect of estriol on the cytology of urethra and vagina in postmenopausal women with genito—urinary symptoms. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 51:29–33

Henriksson L, Stjernquist M, Boquist L, Alander U, Selinus I (1994) A comparative multicenter study of the effects of continuous low-dose estradiol released from a new vaginal ring versus estriol vaginal pessaries in postmenopausal women with symptoms and signs of urogenital atrophy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171:624–632

Bottiglione F, Volpe A, Esposito G, De Aloysio D (1995) Transvaginal estriol administration in postmenopausal women: a double blind comparative study of two different doses. Maturitas 22:227–232

Barentsen R, van de Weijer PH, Schram JH (1997) Continuous low-dose estradiol released from a vaginal ring versus estriol vaginal cream for urogenital atrophy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 71:73–80

Dugal R, Hesla K, Sordal T, Aase KH, Lilleeidet O, Wickstrom E (2000) Comparison of usefulness of estradiol vaginal tablets and estriol vagitories for treatment of vaginal atrophy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 79:293–297

Kanne B, Jenny J (1991) Local administration of low-dose estriol and vital Lactobacillus acidophilus in postmenopause. Gynakol Rundsch 31:7–13

Raz R, Stamm WE (1993) A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med 329:753–756

Capobianco G, Donolo E, Borghero G, Dessole F, Cherchi Pl, Dessole S (2012) Effects of intravaginal estriol and pelvic floor rehabilitation on urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285:397–403

Dmochowski RR, Miklos JR, Norton PA, Zinner NR, Yalcin I, Bump RC (2004) Duloxetine urinary incontinence study group. Duloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of Noth American women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol 170:1259–1263

Berghmans LCM, Hendrikis HJM, Bo K, Hay-Smith EJ, de Bies RA, van Waalwijk, van Doorn ESC (1998) Conservative treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Urol 82:181–189

Castro RA, Arruda RM, Zanetti MRD, Santos PD, Sartori MGF, Girao MJBC (2008) Single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no active treatment in the management of stress urinary incontinence. Clinics 63:465–472

Leriche B, Conquy S (2010) Guidelines for rehabilitation management of non-neurological urinary incontinence in women. Prog Urol 20:S104–S108

Archer DF (2010) Efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. Menopause 17:194–203

Ishiko O, Hirai K, Sumi T, Tatsuta I, Ogita S (2001) Hormone replacement therapy plus pelvic floor muscle exercise for postmenopausal stress incontinence. A randomized, controlled trial. J Reprod Med 46:213–220

Schar G, Kochli OR, Fritz M, Heller U (1995) Effect of vaginal estrogen therapy on urinary incontinence in postmenopause. Zentralbl Gynakol 117:77–80

Lose G, Englev E (2000) Oestradiol-releasing vaginal ring versus oestriol vaginal pessaries in the treatment of bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms. BJOG 107:1029–1034

Bhatia NN, Bergman A, Karram MM (1989) Effects of estrogen on urethral function in women with urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160:176–181

Hilton P, Stanton SL (1983) The use of intravaginal estrogen cream in genuine stress incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 90:940–944

Sturdee DW, Panay N (2010) International Menopause Society Writing Group. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 13:509–522

Jaisamrarn U, Triratanachat S, Chaikittisilpa S, Grob P, Prasauskas V, Taechakraichana N (2013) Ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli in the local treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 16:347–355

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capobianco, G., Wenger, J.M., Meloni, G.B. et al. Triple therapy with Lactobacilli acidophili, estriol plus pelvic floor rehabilitation for symptoms of urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289, 601–608 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-3030-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-3030-6