Abstract

Purpose

Work–life balance is an upcoming issue for physicians. The working group “Family and Career” of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) designed a survey to reflect the present work–life balance of female and male gynecologists in Germany.

Methods

The 74-item, web-based survey “Profession–Family–Career” was sent to all members of the DGGG (n = 4,564). In total, there were 1,036 replies (23 %) from 75 % female gynecologists (n = 775) aged 38 ± 7 (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) years and 25 % male (n = 261) gynecologists aged 48 ± 11 years. Statistical analyses were performed using the mean and SD for descriptive analysis. Regression models were performed considering an effect of p ≤ 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

47 % women and 46 % men reported satisfaction with their current work–life balance independent of gender (p gender = 0.15). 70 % women and 75 % men answered that work life and private life were equally important to them (p gender = 0.12). While 39 % women versus 11 % men worked part-time (p gender < 0.0001), men reported more overtime work than women (p gender < 0.0001). 75 % physicians were not satisfied with their salary independent of gender (p gender = 0.057). Work life affected private life of men and women in a similar way (all p gender > 0.05). At least 37 % women and men neglected both their partner and their children very often due to their work.

Conclusions

Female physicians often described their work situation similar to male physicians, although important differences regarding total work time, overtime work and appreciation by supervisors were reported. Work life affected private life of women and men in a similar way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Germany, the number of medical students was rising in the last decades, but the proportion of qualified physicians is falling at the same time [1]. Reasons are most likely the high concentration of work within working time, the large amount of overtime work, the lack of appreciation by the management, the low salary in relation to the high responsibility and in total the low work–life balance [2, 3]. Due to these factors, young physicians head toward other countries with a better work–life balance, a good educational system or higher salaries [4, 5]. Alternatively, they decide to leave patient-based medicine and work for the pharmaceutical industry or accept occupations in the consultative or administrative field.

Another important factor is the rising number of female physicians who want to combine family life and their career. At present, female physicians are still underrepresented in higher positions and in higher academic qualifications [2, 6]. Lately, we have shown that most gynecologists do not believe in the compatibility of family and career [7]. Female gynecologists in higher hierarchic positions have fewer children than their male counterparts [7]. Not only female, but also male physicians arrange and adapt their career to facilitate a better work–life balance [2, 8]. Therefore, work–life balance is an upcoming issue which needs to be addressed.

To study the current work–life balance and satisfaction with work life and private life of female and male gynecologists the “Family and Career” working group of the German Society for Gynaecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) designed a web-based survey. The questions addressed not only work–life balance in general, but also satisfaction with work and salary and neglect of private affairs. To improve the current work–life balance in future, the objective of our study was to identify difficulties in work and private life. In addition we focused on the quantity and quality of work (job satisfaction), as well as quality of private life.

Methods

Sample

A web-based questionnaire entitled “Profession–Family–Career” was e-mailed to all registered members (n = 4,564) of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) in November 2009. In total 1,036 (23 %) members responded to the survey including 75 % female (n = 775) and 25 % male (n = 261) gynecologists. To validate the survey, a pilot study was conducted initially on 98 female and male gynecologists. Next, as a response to inconsistent answers and critical feedback, several of the questions were rephrased. For the main study, an invitational letter containing access information to the web-based questionnaire entitled “Profession–Family–Career” was e-mailed to all registered DGGG members in November 2009. After 5 weeks, i.e. early January 2010, the DGGG members were sent written reminders with the response deadline expiring in early March 2010. The mean (±standard deviation [SD]) age of all participants was 40 years (±9 years). Since women (38 ± 7 years) were on average approximately 10 years younger than men (48 ± 11 years), effects of gender and age were potentially confounded (p < 2.2E−16, see also Table 1).

Survey

The 74-item, web-based German-language questionnaire “Profession–Family–Career” (German title: “Beruf–Familie–Karriere”) was designed by the DGGG’s “Family and Career” Working Group (members of the working group were mostly hospital-based practicing gynecologists in different parts of Germany, represented by Prof. R. Kreienberg) in cooperation with the Institute for Medical Sociology at Charité University Medicine Berlin (Dr. Susanne Dettmer). The survey contained questions concerning the respondents’ current professional and personal situations, for example their family- and job-related day-to-day burden, family- and job-related goals and wishes (e.g. desire to have children, child care, career, etc.) and their current work–life balance. The answers of the survey were anonymized. Survey design and data collection were both done by utilizing the web-based survey tool SurveyMonkey.com [9]. The survey is accessible in electronic form (HTML, PDF) on the publisher’s homepage as a supplement of the previous publication [7].

Statistical analysis

The present study was undertaken to specifically examine work–life balance and differences at work related to gender. Since there was substantial confounding by gender and age (see Table 1), age and gender were modeled simultaneously as independent variables to derive age-adjusted effects of gender. Descriptive data (e.g. percentages, means) corresponded to the observed values and were not adjusted. Percentages were reported after excluding missing values to improve the comparability of data between groups.

In total, 13 questions on work–life balance were examined with regression models including effects of age and gender. In total, 26 tests were performed of which 13 were related to the effects of gender. A conservative Bonferroni adjustment would result in a local type I error threshold of α = 0.05/26 ≈ 0.002. However, the local type I error was not adjusted to correct for false-positive results caused by multiple tests. Effects with p ≤ 0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant. Nevertheless, we reported all tests conducted, as proposed by Proschan and Waclawiw [10], to enable readers to assess the relevance of the results.

Data were collected using questionnaire items and rating scales with two or more ordered categories. Since we examined the data on an item level, we used an ordinal (cumulative link) regression model as described by Agresti [11] to make optimal use of the available data while preserving the data structure. The analysis was conducted using the statistics software R (V2.14, R Core Development Team, 2011) with package ordinal.

Results

The basic demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Detailed demographics were described previously [7].

Work–life balance

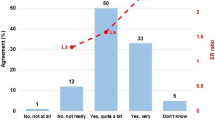

47 % women and 46 % men were not satisfied with their current work–life balance (Table 2). Older physicians were more satisfied than younger colleagues (z = −2.88, p = 0.004), but there was no significant difference between women and men. Although only 2 % of the women and 9 % of the men reported that work life was more important to them than private life (see also Fig. 1), there was no gender effect after adjusting for age. For the majority of women (70 %) and men (76 %), private life and work life were equally important. However, age was positively associated with the importance of work life (z = 5.77, p < 0.001). Approximately 61 % women and 89 % men worked full-time, which was significantly associated with both age (z = −4.18, p < 0.001) and sex (z = 6.78, p < 0.001). Older physicians or women worked more often part-time. In addition to contract work time, at least 90 % women or men stated to work overtime (not differentiating by whether this was paid overtime or unpaid overtime, see also Fig. 1). Older physicians (z = 1.99, p = 0.0465) or male physicians (z = 7.72, p < 0.001) reported more overtime work than younger or female physicians. Although most female (61 %) and male (46 %) physicians preferred a weekly work time between 21 and 42 h per week independent of age, male physicians preferred longer working hours than female physicians (z = 9.22, p < 0.001). In spite of these differences, both women (49.39 %) and men (58.15 %) preferred to reduce their weekly work time independent of age or gender.

Since we observed significant gender differences regarding contract work time and overtime work, we further investigated whether any gender-related interaction effects were present. In particular, we asked, whether especially women in part-time jobs worked overtime. We observed significant interaction effects between gender and contract work time (z = 2.00, p = 0.045) and between gender, age and contract work time (z = −2.18, p = 0.030) in the overall sample. While men stated to work more overtime with increasing age, women’s overtime work was independent of their age. Similar analysis of full-time (>38.5 h/week) physicians showed that men stated to work more overtime than women (z = 2.47, p = 0.014), and older physicians stated to work more overtime than younger physicians (z = 2.64, p = 0.009). However, no interaction effect was observed.

Job satisfaction

Although 41 % of the women and 48 % of the men felt appreciated by the head of the department, 54 % female and 38 % male physicians were stressed by the lack of appreciation shown by the head of the department (z = −2.33, p = 0.0196, Table 3). Age was not associated with feelings of appreciation (z = −0.75, p = 0.45). The majority of women (71 %) and men (76 %) felt respected by their colleagues independent of sex and age. Independent of gender, about 75 % of female and male physicians did not think that their salary was appropriate. Furthermore, two-thirds of all physicians were stressed about their salary. However, with increasing age respondents better accepted their salary and felt less stressed about it (z = −3.15, p = 0.002).

Personal affairs

73 % women and 66 % men neglected their hobbies very often because of work, although there was no significant difference between females and males or younger and older physicians in general (Table 4). About 63 % women and 61 % men neglected their social life very often. However, older physicians considered their social life more important than younger colleagues (z = −3.25, p < 0.001). About 39 % women and 37 % men lost sight of their partner very often without effects of age or gender. Finally, 36 % women and 42 % men neglected their children very often. Again, there were no differences between female and male or younger and older physicians.

Comment

The present study conducted by the DGGG’s “Family and Career” Working Group constitutes the first comprehensive survey conducted on current work–life balance and job satisfaction of female and male gynecologists in Germany.

Our study shows no differences in the current work–life balance of female and male gynecologists, whereas we need to point out that indeed about half of all gynecologists were not satisfied. This confirms other surveys among gynecologists, which show that only half of respondents were able to balance their work and personal life [12]. A survey among plastic surgeons showed an association of diminished work–life balance due to working hours more than 60 h/week and having emergency room call responsibilities [13]. The study of Thangaratinam et al. [12] demonstrated that the reasons for the unbalanced work life situation are mostly the dissatisfaction with the social life, family life and “fun” time. This is consistent with our respondents who neglected very often their social life, their families and their hobbies because of work. Therefore, reducing working time may offer more time for social and family life and may alter work–life balance positively. In our survey, the gynecologists wanted to reduce their actual working time to part-time independent of gender. This is in agreement with other studies showing the desire to work part-time [14, 15]. Henry et al. [14] performed a survey among obstetrics and gynecology trainees with the focus on the attitude toward part-time with the result of 90 % support of part-time. While addressing the question of part-time working we were wondering if the gynecologists need to work overtime and if this has an association with gender or with part-time working. Interestingly, 90 % of gynecologists worked overtime in general. While older aged men more often worked overtime than younger male gynecologists, there was no difference of age in female gynecologists. Concerning part-time working there was no difference in overtime work of female and male gynecologists, but our results implicate that men worked more overtime than women in full-time jobs. This might be due to the high amount of higher hierarchic positions of older male respondents with a high amount of administrative tasks, organization outside the clinical practice or representation jobs. On the other hand, the pure amount of overtime work is measured, which does not reflect the efficacy or the quality of work [16].

In our study, the respondents independent of gender stated that work life and private life do have the same personal impact and are equally important to them. Besides the question about the perfect amount of work and working overtime, the satisfaction with the job has a high impact on work–life balance. Therefore approval with the own work is fundamental and more than 40 % of our respondents feel a satisfying appreciation by their head of department and—even more important—more than 70 % feel well respected by their colleagues. However, noticeable is the fact that only 25 % of the gynecologists are satisfied with their salary whereas most of them are not and those who are dissatisfied are mostly stressed about this. This is in accordance with other data, presenting the desire of salary improvement [3, 12] showed that income was positively associated with personal satisfaction.

Limitations

Although the response rate of 23 % appears low at first glance, it must be considered that most physicians receive many e-mail inquiries hardly having the time to answer them alongside their routine clinical work. However, response rate of physicians (averaged 54 %) is known to be less than in other professions (about 13 %) [17] and several surveys in obstetrics and gynecologists came off with a worse response rate. Henry et al. [14] even reported a disappointing response rate of 20 % and Gobern et al. [18] about 34 %. Therefore, our low response rate is consistent with those of other surveys of physicians and should not be interpreted as a weakness. In their 2006 survey, for instance, Becker et al. [19] had a response rate of 29 % among residents in gynecology.

Conclusion

Not only female but also male gynecologists want to work part-time and reduce the total amount of working time. Therefore, we state that it is the generation rather than the gender which changes the standards of working time; it forces established practices to change to a more flexible work time and to seek alternative ways for the individual academic career.

References

ärztezeitung.de http://www.aerztezeitung.de/politik_gesellschaft/berufspolitik/article/617876/verbaende-aerztemangel-deutschland-spitzt.html. Accessed 22 Apr 2012

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, Bauer G, Häemmig O, Knecht M, Klaghofer R (2010) The impact of gender and parenthood on physicians’ careers—professional and personal situation seven years after graduation. BMC Health Serv Res 10:40

Leigh JP, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL (2009) Physician career satisfaction within specialties. BMC Health Serv Res 9:166

Kopetsch T Dem deutschen Gesundheitswesen gehen die Ärzte aus!, http://www.aerzteblatt.de/down.asp?typ=PDF&id=6100. Accessed 22 Apr 2012

Deutsches Ärzteblatt Archiv “Geschlechtsspezifische Berufsverläufe: Unterschiede auf dem Weg nach oben” (24 January 2003), http://www.aerzteblatt.de/v4/archiv/artikel.asp?id=35261. Accessed 13 Mar 2011

Reed V, Buddeberg-Fischer B (2001) Career obstacles for women in medicine: an overview. Med Educ 35:139–147

Hancke K, Toth B, Igl W, Ramsauer B, Wöckel A, Jundt K, Ditsch N, Bühren A, Gingelmaier A, Rhiem K, Vetter K, Friese K, Kreienberg R (2012) Career and Family—is it compatible? Gebfra 72:403–407

Lambert EM, Holmboe ES (2005) The relationship between specialty choice and gender of US medical students, 1990–2003. Acad Med 80:797–802

SurveyMonkey: Kostenloses Softwaretool für Onlineumfragen & -fragebögen http://de.surveymonkey.com/home.aspx. Accessed 15 Mar 2011

Proschan MA, Waclawiw MA (2000) Practical guidelines for multiplicity adjustment in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 21:527–539

Agresti A (2002) Categorical data analysis, Chap 7.3. Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, p 282ff

Thangaratinam S, Yanamandra SR, Deb S, Coomarasamy A (2006) Specialist training in obstetrics and gynecology: a survey on work–life balance and stress among trainees in UK. J Obstet Gynaecol 26:302–304

Streu R, McGrath MH, Gay A, Salem B, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK (2011) Plastic surgeons’ satisfaction with work–life balance: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg 127:1713–1719

Henry A, Clements S, Kingston A, Abbott J (2012) In search of work/life balance: trainee perspectives on part-time obstetrics and gynecology specialist training. BMC Res Notes 5:19

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, Klaghofer R (2008) The new generation of family physicians—career motivation, life goals and work–life balance. Swiss Med Wkly 138:305–312

“Feminisierung” der Ärzteschaft: Überschätzter Effekt (27 May 2011) http://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/91442/Feminisierung-der-Aerzteschaft-Ueberschaetzter-Effekt?src=search. Accessed 18 May 2012

Kellerman SE, Herold J (2001) Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 20:61–67

Gobern JM, Novak CM, Lockrow EG (2011) Survey of robotic surgery training in obstetrics and gynecology residency. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 18:755–760

Becker JL, Milad MP, Klock SC (2006) Burnout, depression, and career satisfaction: cross-sectional study of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol 95:1444–1449

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Evelyn Klein for the careful reading and editing of the final article. The authors wish to thank Dr. Susanne Dettmer for advisory work with the survey. The questionnaire was supported by the German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hancke, K., Igl, W., Toth, B. et al. Work–life balance of German gynecologists: a web-based survey on satisfaction with work and private life. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289, 123–129 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-2949-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-2949-y