Abstract

Background

Combining family and career is increasingly taken for granted in many fields. However, the medical profession in Germany has inadequately developed structures. Little is known regarding the satisfaction of physicians working part-time (PT).

Methods

This Germany-wide on-line survey collected information on the working situation of PT employees (PTE) in gynecology. An anonymous questionnaire with 95 items, nine of which concerned PT work, was sent to 2770 residents and physicians undergoing further specialist training.

Results

Of the 481 participants, 104 (96 % female, 4 % male) stated they worked PT, which is greater than the national average. 94 % of all women and 60 % of all men would work PT for better compatibility between work and family life. The PTE regularly work night shifts (NS) (96 %) and weekends (98 %). The number of monthly NS (median 5–9) was not different between the full-time (FT) employees and the PTE who work >75 %. Only when the working hours are reduced by 25 % or more, there are fewer NS (median 1–4) PTE that have a desire for fewer NS. The classic PT model is seldom realized; over 70 % of PTE work whole days, while other working models do not play a major role in Germany. On-call models were subjectively declared to have the best family friendly work-life balance.

Outlook

The results obtained indicated that structures must be developed that to address the problem of childcare and the long working hours to ensure comprehensive medical care from specialists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The proportion of women in medicine is increasing. Today, 60 % of university graduates are female. Physician statistics show that working female physicians have increased to 45 % of the work force [1–3]. Surveys of university students show that specialty areas, such as gynecology and obstetrics, are being particularly inundated with women, as four times as many female university graduates can imagine themselves doing a specialist residency in these specialty areas (20 versus 5.1 % of male students) [4]. Physician statistics support this tendency with the currently high percentage of female physicians active in gynecology and obstetrics of 48.5 % [5]. This is problematic because according to the Medical Association of German Doctors (Hartmannbund), the majority of women do not wish to perform operations [6]. The current proportion of women active in surgical specialty areas is around 19 % [7]. The argument put forward for this is that reconciling professional and family life is particularly difficult in the surgical specialty areas for both men and women. This was also the conclusion of the former Commission for Family and Career of the German Association for Gynecology and Obstetrics (Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e.V.—DGGG) [8, 9]. Combining family and career is increasingly a matter of course in many sectors and countries. However, the medical profession has not yet adequately developed the necessary structures [2]. Further surveys of younger generations have shown that a good work-life balance is valued equally highly regardless of sex [10]. Some initiatives, such as the Alliance for Young Physicians, have demanded better professional conditions for both sexes so that family and work can be better balanced [11]. Their aims are to stave off a shortage of new physicians, to increase the attractiveness of the medical profession, and to preserve the efficiency of individual physicians. Reconciling family and professional life is particularly difficult in obstetrics due to the 24-h care required 365 days a year. Among other aspects, this Germany-wide survey on the work situation in the field of obstetrics collected information on young gynecologists’ experiences with part-time (PT) work, with the aim of capturing the status quo and pointing out opportunities for improvement.

Methods

Questionnaire instrument

The basis of this publication is an online questionnaire developed by the authors to capture the service models and working hours via a total of 93 questions and two comment fields, including nine items on actual or potential PT work (see appendix). Satisfaction was queried using a scale analogous to German school grades (1 = “very good”, 6 = “poor”).

Study population

Via the newsletter of the Youth Forum of the DGGG, the link to the questionnaire was sent to 2770 members completing a gynecological residency or fellowship. Further participants were recruited via the Thieme Gyn community platform, through personal contacts, and through a call for participants in the journal “Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde” (“Obstetrics and Gynecology”) in the time period from Feb 17, 2015, to May 15, 2015. Data were collected using http://www.surveymonkey.de. Participation consent was obtained at the beginning of the study. Participants were excluded if consent was not given and, for this sub-analysis, if they did not work PT in obstetrics. The statistical analysis was carried out using Graphpad Prism 5.0 and the statistical software “psppire.exe 0.8.5”. For independent, non-normally distributed samples, the Mann–Whitney test was performed, for dependent samples the t test, and for categorical variables the Chi-squared test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population, work places, and professional positions of physicians working part-time

481 participants took part in the survey. After exclusion of those who were not currently working in obstetrics as well as those who had not agreed to their data being evaluated, the results of 437 participants were available for evaluation. In this publication, data from 401 participants who indicated the extent of their employment are evaluated, which enabled a subgroup analysis of PT and full-time (FT) employment. 104 physicians stated that they were employed PT at the time of data collection. There was a strong statistical difference in the proportion of FT employees (74 %, p < 0.0001). The characteristics of the participants are show in Table 1. In total, 60 % intended to become qualified specialists in the field, and 27 % intended to pursue a further fellowship qualification. Those who did not provide answers were mainly female (n = 14; male n = 7) and below 40 years old (<30 = 7, 30–35 = 5, 36–40 = 3, >40 = 5, >60 = 1).

As a professional goal, 17 % of PT employees were striving for a senior physician position, 11 % a specialist position in the hospital, and 3 % a head medical position. The largest significant difference between the PT and FT employees was the goal of opening a private practice, with 38 % of PT employees versus 19 % of FT employees aiming for this (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Of physicians employed PT, 16 % lived in a household without an under-aged child. On average, physicians employed PT lived with 1.5 children in a household, and the size of the household was 2.3 individuals. This is highly significantly different from physicians employed FT, with an average number of children of 0.5 (p < 0.0001) and 3.5 individuals (p < 0.0001) per household.

Service model of part-time employees

The existent service models analogous to the German Federal Ministry for Work and Social Issues (“Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales”—BMAS) are shown in Table 2 [12]. Most PT employees (47 %) have positions that are 51–75 % of a FT position. Of these, 32 % have 76–95 % positions, 18 % have 26–50 %, and 1 % have positions less than 25 % of a FT positions. The vast majority of PT employees stated that they regularly work night shifts (96 %) and work on weekends (98 %). The number of night shifts among PT employees (with positions >75 %) was 5–9 shifts per month and is not different from the median number of night shifts among FT employees. Among employees with 74 % of a FT position or less, the median number of night shifts was one to four, which is statistically different from FT employees (p < 0.0001).

In terms of a “classic part-time variation”, 71 % of the PT employees work full days and have a reduced number of work days per week. 20 % work in a classic part-time model. 2 % work in PT job-sharing models. 1 % of the survey participants are on sabbatical and normally working “PT Invest”. As a further concept that is most strongly associated with the “classic part-time variation”, week-long days off are mentioned. The number of days worked by PT physicians per week is shown in detail in Fig. 2.

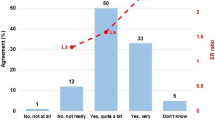

Satisfaction of part-time physicians

The satisfaction of PT and FT employees did not differ in terms of private life (median 2 vs. 2) or their working situation (median 3 vs. 3). Compared to the FT employees, PT employees indicated that they would be more satisfied if they had to work few nights (median 1 vs. 2), but the difference is not statistically significant. The balance between work and private life was evaluated equally negatively by the PT employees and FT employees (median 4 vs. 4). Compared to FT employees, PT employees expressed a desire for reduced working hours significantly less often, except for the number of night shifts. The latter was also equally desired by the FT employees. For the question concerning the favored scheduling model, a majority of all participants would like an on-call system instead of a shift-model (50 % of the entire study population vs. 58 % of the PT study participants), although PT workers wanted fewer on call shifts in general more often. In the question on service models, the on-call model was also rated as the model with the subjectively highest family-friendliness and the best work-life balance by both the entire population and the participants employed part-time. Furthermore, in the free-text comment fields, difficulties obtaining childcare to cover increasingly long working days were often mentioned. Details about this were not investigated. In terms of the estimation of the convenience of the residency, there was no statistical significance between the two groups.

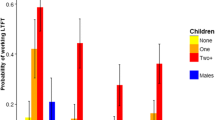

Attitudes of the full-time employees towards part-time employment

297 participants (62 % of complete questionnaires) work FT. Of these, 61 % (n = 180) would work PT for a specified time period to better reconcile family and professional life, 22 % would “maybe consider this”, and 17.9 % said this was not an option for them. The proportion of these potential PT employees (answered “yes” or “maybe”) was significantly smaller among men compared to the women (60 vs. 92 %, p < 0.0001). Age also played a role in the willingness to work PT. PT employment was a potential consideration for 84.8 % of all participants under 50 years of age (n = 277). This proportion decreases with each increasing age group (91.5 % of those <30 years, to 66.6 % of those 41–50 years old), but even beyond 50 years of age, 45 % of physicians currently working FT would be willing to consider working PT. Before 50 years of age, the willingness is significantly higher (p < 0.0001). If PT employment were taken up, 62 % would want a 51–75 % position, 32 % a >75 % position, 4.5 % a 26–50 % position, and 1.2 % a maximum of a 25 % position. The subgroup analysis showed that for women, the largest proportion preferred 50–75 % positions, while for men the largest proportion preferred positions with more than 75 %.

Discussion

The medical field is undergoing a change that is affecting not only the structure of care, but also the working conditions of employees. This survey on the working conditions of residents and specialists undergoing further training showed a PT employee contingent of 26 %. In this evaluation of a cohort of 481 participants, considerably more physicians in obstetrics pursued PT work compared to the 2014 German federal average of 19.9 % among employees in general. This emphasizes the relevance of this issue in our specialty area [13]. The proportion of females working within the gynecological and obstetrical field comprised approximately 65 % according to calculations based on data from the German Medical Association. In this study, the proportion of women among the participants was 77 %. Both women and men indicated that they would consider PT employment. In addition to the already high proportion of female physicians employed PT, 94 % of all women would work PT to better reconcile family and career—significantly higher than men (60 %). Previous studies among pediatric residents in the USA have also shown that in a specialty area with a high proportion of women, there is also an increased number of PT employees [14–16].

Considering that 83 % of PT employees in our study collective live in a household with children, the argument that the “family” is a strong motivation for working PT appears to be supported. As well, the number of children generally in PT households is significantly higher on average than for FT employees. Our results confirm this trend in obstetrics in Germany and may also indicate a similar development for male colleagues in the future. A study among radiologists has also shown similar results [19]. This development is also reflected in the family and sociopolitical framework conditions, not the least of which are the changes to the Federal Act for Parental Leave and Parental Allowance [Bundeselternzeit- und Elterngeldgesetz (BEEG)]. The aim of these measures is to promote better compatibility between family and career, including increasing the number of PT positions in hospitals [17]. The new “Elterngeld Plus” (“Parental Allowance Plus”) has made taking on PT work as part of parental leave particularly attractive for men as well as academics in general. These changes to parental allowance led to an increase in men taking parental leave to 1.2 % in 2014 [18]. Conversely, an adequate salary and preservation of professional status after returning to work after parental leave appear to still be the most important reasons for being for or against taking parental leave [20]. The reasons for reducing working hours in terms of reconciling career and family were not collected in this survey. However, a 2001 survey of gynecological residents showed that the second most frequent reason for reducing working hours was the need for more time for oneself personally [21]. Changes to and prioritization of personal organization of day-to-day life by generation “X–Y–Z” accompanied by a redesign of working hours and the actual implementation of desires to work PT are to be expected [22].

Furthermore, physicians are increasingly pulling back entirely from direct patient care and most often state the difficulties combining career and family life as well as the burden of shift work as reasons [10, 23]. Our study shows that PT work is also significantly increasingly aimed for in private practice settings.

It is of interest that those working in more than 75 % positions work on average the same number of night and weekend shifts as FT employees. Against the backdrop of the non-discrimination law for PT employees [§4 Part-time and Limited Employment Act (§4 Teilzeit- und Befristungsgesetz)], the results show that similarly high demands are placed on these two groups in this regard. In addition, PT workers wanted fewer on call shifts significantly more often. Furthermore, a higher subjective burden due to night shifts was generally reported by the PT employees compared to the FT employees. It is known that working nights and weekends are particularly stressful forms of work, and employees that work long hours are subjected to increased risks for disease [24, 25]. In addition to these health risks, there are also proven restrictions placed on family life and taking part in social activities [26, 27]. This is also apparent in our study, as the work stress ascertained and the comments in the free text fields clearly show a strong connection between difficulties finding childcare and increasing length of working hours. Due to the size of the groups, a detailed sub-group comparison (number of night shifts: none, 1–4, 5–9, 10 or more) with other surveys is not possible [28].

Furthermore, in our analysis there was no evidence that PT employees are more satisfied in general compared to FT employees. As possible causes for this, reasons given in the free text comments concerning social reasons such as impeded childcare when working night shifts and organizational work issues can be considered. The international literature confirms flexible and needs-based work schedule models as being family friendly [29, 30]. It must also be mentioned, however, that a general dissatisfaction in the medical work environment and in obstetrics is to be expected; a 2012 analysis found that in general every third person is dissatisfied with his/her working situation [29].

The characterization of the PT model in this investigation shows an unexpected high number of the part-time “Classic Vario”, with full working days but a reduced number of working days. This is surprising; given the oft-mentioned lack of company child care opportunities and limited opening times of public childcare facilities, particularly for night shifts and/or early starting and late ending times, one would assume that the “classic PT” model would be the most common. It can be assumed that the viability of the operational interests influences the respective PT model. This is also shown by the frequent use of the “PT Classic Vario” model, which, depending on the configuration, can be integrated into the work flow of a hospital. This assumption is based on the numerous free text comments describing the perception that PT employment is perceived as difficult by the person responsible for the scheduling and hinders a smooth organization of the department. In addition, it shows that the usage of better plannable PT models such as daily or weekly job sharing or adjusting the department organization to implement “classic PT” rarely occurs. Complex work schedule demands require detailed daily planning to suitably address the demands of medical care and the desires of the employees, and the time needed for this kind of scheduling is often not allocated. An example for an opportunity to improve this could be to have a dedicated “scheduler” position in the personnel requirements analysis.

In addition to the sociodemographic changes, the changes to the legal act governing working hours in 2009 (Arbeitszeitgesetz) and the case law of the European Court of Justice (EJC) as well as regarding on-call duty time as working hours had a massive impact on the working hours and scheduling models in hospitals. The unchanged need for medical services around the clock must be compensated for through more personnel. An indisputable relative lack of physicians is also developing, in particular due to demographic changes, but physicians working PT are also contributing to this lack of physicians [31]. It will, therefore, become increasingly more challenging for hospitals to recruit applicants. It will be even more difficult later to recruit well qualified specialists during possible leaves of absence, for example due to parental leave. This is shown by the over-representation of PT employees who want to go into private practice later. Obstetrics as an employer will be unable to avoid investing in “physicians” as a resource to continue to be competitive in the future [32]. However, this is not restricted to a purely financial investment; tactical actions according to transparent principles to balance as many single interests as possible are demanded and structural rethinking is necessary. The quota of PT employees as well as personal and professional development goals will have to be considered more carefully in the future to ensure the sustainability of medical care [16]. The heterogeneous care structures require individual concepts for the local circumstances. Personnel deployment and schedule planning are tasks for which better cooperation between the departments and occupational physicians as well as the administration and employee representative committees might become necessary in the formation of a healthy work place and healthy work conditions to sustainably guarantee comprehensive medical care.

Limitations of the survey

With 481 participants this survey does not cover the entire collective of physicians working in gynecology and obstetrics; it tries solely to reflect a representative selection. Physicians of all positions within the obstetrics department took part in this survey. The primary audience of this questionnaire included residents or those pursuing further specialized education; however, further subgroups were also represented that are very small as a result (for example department heads). As a result, some of the results cannot be interpreted, or at least this would only be possible with additional surveys. The proportion of participants at perinatal centers was particularly large. Regarding the data concerning PT work, the results of this subgroup appear to be especially valid but limits general statements for all care structures. Further limitations of this work include the extensive subgroup analyses of a survey intended to collection information on the general working conditions in obstetrics. Therefore, some aspects, such as problems specific to PT work, reasons for working PT, and type and extent of the work of the spouse, were not systematically collected to better understand the range and conditions of part time work. The remarks in the free text comments could at the most give indications for causal connections. With 104 PT employees, this cohort is small, but it is still within the range of research papers on reconciling family and professional life. Distortions are possible in small study populations. With a response rate of only 17.8 %, it is possible that a larger proportion of PT employees participated in the survey compared to FT employees, based on federal averages, which could have introduced an additional bias. However, other surveys like this one have garnered similar participation rates. The data presented here on the scheduling models of PT employees and the most useful duty models are in accordance with the expected results of the Jungen Forum working group that designed this survey as well as with the daily experiences of the authors.

References

Heueck L (2008/2013) Die Karriere der Anderen. Die Zeit online. http://www.zeit.de/campus/online/2008/07/karriere-aerztinnen. Accessed Oct 2016

Rapp-Engels RG, Ben KH, Wonneberger C, van den Bussche H (2012) Memorandum zur Verbesserung der beruflichen Entwicklung von Ärztinnen. ZFA (Z Allg Med) 88(7/8)

Meyer-Radtke M (2009) Aus Herr Doktor wird Frau Doktor. In: Die Zeit. http://www.zeit.de/karriere/beruf/2009-12/feminisierung-medizin. Accessed Oct 2016

Gibis B, Heinz A, Jacob RD et al (2012) Berufserwartungen von Medizinstudierenden. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109:327–332

Osterloh F (2014) frztestatistik: Mehr frztinnen, mehr Angestellte. Dtsch Arztebl Int 111:672–673

Hartmannbundes (2012) http://www.hartmannbund.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Umfragen/2012_Umfrage-Medizinstudierende.pdf. Accessed 16 Oct 2016

Knauss H (2013) Über die (Un-)Vereinbarkeit von Kind und Karriere. UroForum 4/2013 S.14–15

Hancke K, Igl W, Toth B et al (2014) Work-life balance of German gynecologists: a web-based survey on satisfaction with work and private life. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289:123–129

Hancke K, Toth B, Igl W et al (2012) Career and family—are they compatible?: results of a survey of male and female gynaecologists in Germany. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 72:403–407

Kasch R, Engelhardt M, Forch M et al (2016) Physician shortage: how to prevent generation Y from staying away—results of a nationwide survey. Zentralbl Chir 141:190–196

Bündnis Junge Ärzte (2016) Positionspapier-Vereinbarkeit von Familie und Karriere—wo bleibt der Wandel in den Köpfen? Der Internist 57(3):273–274

Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Teilzeitmodelle http://www.bmas.de/DE/Themen/Arbeitsrecht/Teilzeit/Teilzeitmodelle/inhalt.html. Accessed 16 Oct 2016

Statistisches Bundesamt Destatis (2014) Atypische Beschäftigung. https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesamtwirtschaftUmwelt/Arbeitsmarkt/Erwerbstaetigkeit/TabellenArbeitskraefteerhebung/AtypischeBeschaeftigung.html. Accessed 16 Oct 2016

Cull WL, Caspary GL, Olson LM (2008) Many pediatric residents seek and obtain part-time positions. Pediatrics 121:276–281

Cull WL, Mulvey HJ, O’Connor KG et al (2002) Pediatricians working part-time: past, present, and future. Pediatrics 109:1015–1020

Cull WL, O’Connor KG, Olson LM (2010) Part-time work among pediatricians expands. Pediatrics 125:152–157

Deutscher Bundestag (2014) Drucksache 18/2583. http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/18/025/1802583.pdf. Accessed 16 Oct 2016

Statistisches Bundesamt DESTATIS (2014) Personen in Elternzeit. https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/Indikatoren/QualitaetArbeit/Dimension3/3_9_Elternzeit.html. Accessed 16 Oct 2016

Bundy BD, Bellemann N, Burkholder I et al (2012) Compatibility of family and profession. Survey of radiologists and medical technical personnel in clinics with different organizations. Radiologe 52:267–276

Engelmann C, Grote G, Miemietz B et al (2015) Career perspectives of hospital health workers after maternity and paternity leave: survey and observational study in Germany. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 140: e28–e35

Defoe DM, Power ML, Holzman GB et al (2001) Long hours and little sleep: work schedules of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 97:1015–1018

Schmidt C, Mˆller J, Windeck P (2013) Arbeitsplatz Krankenhaus: Vier Generationen unter einem Dach. Dtsch Arztebl Int 110:928–933

Jerg-Bretzke L, Limbrecht K (2012) Where have they gone?—a discussion on the balancing act of female doctors between work and family. GMS Z Med Ausbild 29:doc19

Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST et al (2015) Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet 386:1739–1746

Batty GD, Shipley M, Smith GD et al (2015) Long term risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: influence of duration of follow-up over four decades of mortality surveillance. Eur J Prev Cardiol 22:1139–1145

Lambert TW, Smith F, Goldacre MJ (2014) Views of senior UK doctors about working in medicine: questionnaire survey. JRSM Open 5:2054270414554049

Mache S, Bernburg M, Vitzthum K et al (2015) Managing work-family conflict in the medical profession: working conditions and individual resources as related factors. BMJ Open 5:e006871

Marburger Bund Monitor (2014) https://www.marburger-bund.de/sites/default/files/dateien/seiten/mb-monitor-2014/gesamtauswertung-mb-monitor-2014.pdf. Accessed 16 Oct 2016

Buxel H (2013) Arbeitsplatz Krankenhaus: Was frzte zufriedener macht. Dtsch Arztebl Int 110:494–498

Schooreel T, Verbruggen M (2016) Use of family-friendly work arrangements and work-family conflict: crossover effects in dual-earner couples. J Occup Health Psychol 21:119–132

Osterloh F (2015) Aerztestatistik: Aerrztemangel bleibt bestehen. Dtsch Arztebl 112(16):A–703/B–597/C–577

Bühren A, Dettmer S (2006) Das familienfreundliche Krankenhaus: Vorteil im Wettbewerb durch zufriedenere Ärztinnen und Ärzte. Dtsch Arztebl 103(49):A–3320/B–2891/C–2771

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the survey participants and the DGGG for their support in the online survey and Katharine Taylor for critical reading and her support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest, the authors have had full control of all primary data and that they agree to allow the Journal to review their data if requested.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study as frist slide oft eh online survey. In case consent was not given, the questionnaire could not be answered.

Additional information

J. Neimann and J. Knabl contributed equally.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schott, S., Lermann, J., Eismann, S. et al. Part-time employment of gynecologists and obstetricians: a sub-group analysis of a Germany-wide survey of residents. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295, 133–140 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4220-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4220-9