Abstract

Purpose

The benefit of elective primary tumor resection for non-curable stage IV colorectal cancer (CRC) remains largely undefined. We wanted to identify risk factors for postoperative complications and short survival.

Methods

Using a prospective database, we analyzed potential risk factors in 233 patients, who were electively operated for non-curable stage IV CRC between 1996 and 2002. Patients with recurrent tumors, resectable metastases, emergency operations, and non-resective surgery were excluded. Risk factors for increased postoperative morbidity and limited postoperative survival were identified by multivariate analyses.

Results

Patients with colon cancer (CC = 156) and rectal cancer (RC = 77) were comparable with regard to age, sex, comorbidity, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, hepatic spread, tumor grade, resection margins, 30-day mortality (CC 5.1%, RC 3.9%) and postoperative chemotherapy. pT4 tumors, carcinomatosis, and non-anatomical resections were more common in colon cancer patients, whereas enterostomies (CC 1.3%, RC 67.5%, p < 0.0001), anastomotic leaks (CC 7.7%, RC 24.2%, p = 0.002), and total surgical complications (CC 19.9%, RC 40.3%, p = 0.001) were more frequent after rectal surgery. Independent determinants of an increased postoperative morbidity were primary rectal cancer, hepatic tumor load >50%, and comorbidity >1 organ. Prognostic factors for limited postoperative survival were hepatic tumor load >50%, pT4 tumors, lymphatic spread, R1–2 resection, and lack of chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Palliative resection is associated with a particularly unfavorable outcome in rectal cancer patients presenting with a locally advanced tumor (pT4, expected R2 resection) or an extensive comorbidity, and in all CRC patients who show a hepatic tumor load >50%. For such patients, surgery might be contraindicated unless the tumor is immediately life-threatening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide with more than 900,000 new cases and nearly 500,000 deaths occurring annually [1]. Operation is the gold standard for patients with localized CRC and results in cure in about 50% of patients [2]. However, approximately 20% of patients with CRC are initially seen with synchronous metastases (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) stage IV disease), and their median survival is dismal [3–5]. Curative resection is the treatment of choice for those patients who show solitary liver or lung metastases [6–8]. The majority of stage IV patients, however, have extensive non-resectable metastatic disease (70–80%) [3, 4]. In these patients, palliation is the only intention of treatment. If any operative procedure is considered, morbidity and mortality should be low [9]. It is essential to avoid a prolonged hospital stay in these patients whose life expectancy is limited. Non-curative resection of the primary tumor has been advocated by different authors to prevent local tumor complications such as obstruction, perforation, intractable bleeding, and subsequent emergency operations, particularly during chemotherapy [10–15]. On the other hand, the benefit of this approach has been challenged because palliative resection of the primary tumor might be associated with a significant postoperative morbidity and mortality [16–19]. Thereby, the postoperative recovery period may be prolonged delaying or even precluding chemotherapy or radiation, which are most likely the only treatment strategies that prolong survival in those patients [2, 20, 21]. Some recent studies have put more emphasis on non-operative management of stage IV CRC [18, 22–25]. However, a recent randomized clinical trial revealed that endoscopic stenting of left-sided stage IV colon cancer is associated with an unexpectedly high risk of perforation in patients on chemotherapy [26].

So far, there are only limited data concerning selection criteria to identify candidates for palliative operations. It was the purpose of the current study to analyze postoperative complications after elective non-curative resection of stage IV CRC. We wanted to identify independent prognostic factors for postoperative morbidity and survival. These determinants might help the surgeon to select appropriate patients for palliative resection of the primary tumor. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the largest to evaluate patients who have undergone elective primary tumor resection in stage IV CRC with non-resectable metastases. Our study is also the first to analyze perioperative risk factors separately in stage IV colon and rectal cancer patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

All patients who presented with CRC were entered into a prospective database at our institution and were followed up at regular intervals (every 6 months). For this purpose, we established a specific out-patient clinic with a staff member exclusively responsible for follow-up examinations and prospective data management of CRC patients. Between January 1996 and December 2002, 1,562 patients underwent surgery for primary CRC at our institution. A total of 338 (21.6%) presented with primary stage IV CRC. All datasets of these patients were screened for the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: (1) primary stage IV CRC, (2) non-resectable metastatic disease, and (3) resection of the primary tumor. Exclusion criteria were: (1) primary or secondary resection of metastases, (2) emergency operation (e.g., due to bleeding or obstruction), (3) operation for tumor recurrence, and (4) non-resective operation (enteric bypass, diagnostic laparotomy, diverting stoma). On the basis of the above criteria, 233 of the 338 patients (68.9%) were identified and included in the analysis. It was our policy not to use routine endoscopic stenting, definitive chemotherapy, or radiation as an initial therapy of an intact primary tumor of non-curable stage IV CRC. Therefore, almost all patients had a surgical resection of their primary. Only those patients whose comorbidity did not allow an operation (e.g., American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)-V) or patients who declined any surgical procedure were treated conservatively. Therefore, patients of our study were largely unselected representing an average population of all patients with stage IV CRC and synchronous non-resectable metastatic disease.

Data collection

The following information was prospectively collected for each patient: age, sex, primary diagnosis, tumor-related symptoms, comorbidity, ASA score, carcinoembryonic antigen, site of primary lesion, extent of metastatic spread, degree of hepatic tumor load, depth of local tumor growth (pT), lymph node metastases (pN), grade of tumor differentiation (G), local tumor clearance (R), type of surgery and operative approach, postoperative surgical and general complications, number of relaparotomies, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, hospital length of stay, postoperative mortality, postoperative palliative chemotherapy or chemo-radiation therapy, and survival status until December 31st 2007. The latter two parameters were assessed by direct patient contact or death certificates from the Munich tumor registry and the German resident registry. TNM status of all tumors was adjusted according to the UICC classification of 2002 [3, 27]. All data were entered into a separate FileMaker database for further analysis (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA).

Morbidity

Postoperative morbidity was defined as any postoperative surgical (local) or general (systemic) complication. Anastomotic leakage was defined as any anastomotic dehiscence or leakage of the Hartmann’s stump which was detected by postoperative routine endoscopy, contrast enema, or reoperation, regardless of its clinical relevance. Postoperative hemorrhage includes all postoperative gastrointestinal and intraabdominal bleedings with immediate therapeutic consequences (e.g., blood, fluid, or plasma transfusions; endoscopy; angiography; or relaparotomy). Fascial dehiscence and incisional hernia implicate all early or late dehiscence of the abdominal wall. Superficial wound infection was defined as an inflammation or redness of the wound or a secretion from the wound, requiring bed-side irrigation, air dressings, or antibiotic therapy, but no operative revision. Respiratory events included postoperative pneumonia, pleural effusions, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and pulmonary embolism. Cardiac events implicated acute coronary syndromes, cardiac arrhythmia, low cardiac output, or cardiac arrest. Gastrointestinal events were defined as ileus, intestinal ischemia, or infectious diarrhea.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median (range) and categorical variables as total number (percentage). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for all comparisons among continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared by Pearson’s chi-square statistics or Fisher’s exact test for small sample sizes. A p value of 0.05 or less in a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant. Analysis of independent risk factors for surgical and general complications after colorectal surgery was performed by univariate and multivariate analysis. Variables found to be associated with the frequency of complications in the univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were entered into a stepwise logistic regression model for multivariate analysis of risk factors. Overall survival was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier statistics. Cox proportional hazards model was applied for identification of independent prognostic factors. All statistical analyses were performed using a SPSS package (SPSS 14.0, 2006; SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Study population

The study population consisted of 233 stage IV CRC patients with non-resectable metastases, including 156 colon cancer patients (CC) and 77 rectal cancer patients (RC). As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between both groups regarding baseline characteristics such as age, sex, medical risk factors, and ASA score prior to surgery. Tumor-related symptoms were in large part similarly distributed between both groups, but asymptomatic patients were rare (Fig. 1). Patients with colon cancer showed a higher incidence of weight loss and abdominal pain, while changes in bowel habit and rectal bleeding were more common in rectal cancer patients (Fig. 1).

Tumor load and staging

Most frequently, the primary tumor was located in the rectum (33.0%), followed by the sigmoid (28.3%) and the right colon (24.8%). Table 1 provides details on primary lesions and extent of metastatic spread. Advanced local tumor stages were observed in most patients (Fig. 2). More than 95% of patients had pT3–4 tumors, more than 80% of tumors had lymphatic involvement (pN1–2), around 70% of tumors where poorly differentiated (high-grade tumors), and local tumor clearance (R0) was achieved in around 80% of patients (Fig. 2). Frequency of hepatic and extrahepatic spread as well as extent of hepatic tumor load was comparable between colon and rectal cancer patients (Table 1). More than 90% of patients had liver metastases, and bilobular spread was common in both groups (75%). More than 30% of patients had an extensive involvement of the liver (hepatic parenchymal replacement by metastases >50%).

Comparison of tumor characteristics of 156 colon cancer and 77 rectal cancer patients: a pT stage of primary colon cancer was more advanced compared to rectal cancer; b the incidence of lymph node metastases; c the extent of liver metastases; d the grade of tumor differentiation; and e the local surgical tumor clearance was similar in both groups. Asterisk, colon cancer vs. rectal cancer: p < 0.05

Surgical procedures

All colorectal resections were elective procedures. The majority of patients underwent a standard oncological operation of the colon or rectum, while 31.4% of colon cancer and 6.5% of rectal cancer patients had a segmental or tubular resection (Table 2). Laparoscopy was performed in less than 10% of cases, and successful laparoscopic resection in less than 5%. A significant difference was found for the rate of stoma construction. More than two thirds of patients with rectal cancer, but only two patients with colon cancer required an enterostomy (Table 2). However, the probability of a secondary closure of the stoma was low (11.1%: CC = 0/2 patients; RC = 6/52 patients).

Surgical and general complications

Types and frequency of surgical and non-surgical complications are shown in Table 3. Differences between stage IV colon and rectal cancer patients were found with respect to the number of anastomotic leaks (including leakage of the Hartmann’s stump) and postoperative wound infections. Those events were significantly more frequent after palliative rectal surgery. The overall surgical complication rate was 40.3% in rectal cancer patients and therefore higher than that in colon cancer patients (19.9%). However, non-surgical complications occurred equally often in patients with colon (29.5%) and rectal cancer (26.0%). In both groups, gastrointestinal dysfunction (ileus, diarrhea), respiratory failure, and deep vein thrombosis were the most common adverse events during the postoperative period (Table 3).

ICU and hospital length of stay

The proportion of patients who needed postoperative intensive care was similar after surgery for colon cancer and rectal cancer, and likewise was the median ICU length of stay. Median postoperative hospital length of stay was 13 days (CC) and 15 days (RC), respectively (Table 3).

Postoperative mortality

Postoperative 30-day mortality was 4.7% in the study population, and no difference was found between colon and rectal cancer (CC 5.1%, RC 3.9%; Table 3). Of the 11 patients who died perioperatively, ten died secondary to a complicated postoperative course, and one patient committed suicide. All of these ten patients had preoperative tumor-specific symptoms, eight had liver metastases, six exhibited an extensive hepatic parenchymal replacement by metastases (>50%), and six underwent reoperations due to surgical complications. Thirty-day mortality was associated with age (≤65 years = 1.6%, >65 years = 8.5%; p = 0.013), ASA score (ASA I–III = 3.5%, ASA IV = 42.9%; p = 0.002), pT stage (pT1–3 = 2.0%, pT4 = 9.5%, p = 0.019), and postoperative complications (no complications = 0.8%, complications = 9.3%, p < 0.0001).

Palliative chemotherapy

Postoperative tumor-specific therapy was given to the vast majority of patients (87.1%), and no difference was found between colon cancer and rectal cancer (CC 86.5%, RC 88.3%; Table 3). 5-FU—leucovorin regimens and oxaliplatin—and/or irinotecan combinations were administered with or without radiation. One-hundred thirty-two patients with colon cancer (84.6%) and 51 patients with rectal cancer (66.2%) received palliative chemotherapy, whereas three colon cancer patients (1.9%) and 17 rectal cancer patients (22.1%) were treated with chemo-radiation therapy. Patients with surgical complications received significantly less often postoperative palliative treatment (72.6% vs. 91.9%, p < 0.001).

Independent determinants of postoperative morbidity

Total postoperative morbidity was high in both groups, but higher in rectal than in colon cancer patients (Table 3). All potential risk factors, which were identified by univariate analysis to be associated with the frequency of postoperative complications (p < 0.05), were entered into a stepwise multivariable logistic regression model. As shown in Table 4, the location of the primary tumor in the rectum was an independent predictor for surgical complications. Moreover, the extent of hepatic spread (hepatic parenchymal replacement >50%) and the degree of comorbidity (more than one organ) were independent risk factors for both surgical and non-surgical complications. Neither general risk factors such as age, sex, symptoms, ASA score, or anemia, nor specific oncological and surgical parameters such as metastatic spread (to more than one organ), positive local resection margins (R1–2), type of surgery (oncological vs. segmental), or stoma construction were predictors of postoperative morbidity in the study population.

Independent predictors of postoperative survival

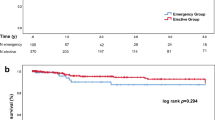

Survival status of patients was recorded until 31st of December 2007. Loss of follow-up was low in both groups of patients (CC 3.8%, RC 2.6%). Colon cancer patients had a median survival of 13.9 month (excluding 30-day mortality), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 49.6%, 6.2%, and 0.7%, respectively. Rectal cancer patients survived 16.6 month in average and had survival rates of 56.7%, 5.9%, and 1.5% after 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. Those differences between groups were not significant. As shown in Table 5, independent prognostic factors for limited postoperative survival were variables, that indicated a large tumor burden such as high pT stage, positive lymph nodes, positive local resection margins, lack of a postoperative tumor-specific therapy, and most significantly advanced hepatic parenchymal replacement (>50%). For most of these patients, median postoperative survival was less than 10 months. Postoperative survival (excluding 30-day mortality) was neither affected by age, sex, symptoms, and comorbidity of patients, nor by the primary tumor site (colon or rectum), tumor grade, metastatic spread (to more than one organ), or type of surgery (oncological vs. segmental). Relevant Kaplan–Maier plots for postoperative survival are shown in Fig. 3 .

Prognostic factors for postoperative survival after palliative resection of primary tumors: a survival curves (Kaplan–Meier) were similar for patients with stage IV colon cancer and rectal cancer. Significant differences of postoperative survival (p < 0.05 according to log rank test) were found for pT stage (b), lymph node metastases (c), local resection margins (e), postoperative radiation or chemotherapy (f), and most significantly, for the extent of hepatic metastases (d)

Discussion

The role of primary tumor resection in stage IV CRC has been a matter of debate. There is only little evidence that removal of the primary cancer contributes to improved long-term survival in patients who present with synchronic non-resectable metastases. Most of the published studies, which reported a survival benefit for resected vs. non-resected patients, rather reflect a selection bias towards more favorable cases than an effect of surgical treatment [11, 14, 16, 28–33]. None of those retrospective studies could demonstrate an equivalence of treatment groups with respect to demographics, comorbidity, and tumor burden. Some more recent studies did not show that patients who were treated surgically lived longer than those who were not [18, 19, 23, 34]. The value of tumor resection might therefore not be defined primarily through its capability to prolong patient survival, but rather through its potential to avert local tumor complications and hospital admissions. Emergency operations for local complications will be required in up to one third of the patients who initially undergo non-surgical treatment of the primary. Emergency operations in those patients, however, were recognized to be associated with a very high risk of perioperative complications and hospital mortality (20–40%) [4, 11, 19]. Elective tumor resection, on the other hand, has been advocated to prevent major complications such as acute obstruction, hemorrhage, and perforation [10–15, 31]. It has been recognized that chemotherapy in general and newer targeted drug therapies in particular (e.g., by bevacizumab or cetuximab) may result in bleeding, tumor perforation, and other severe complications of an intact primary [35]. For those reasons, initial palliative resection of the primary tumor before starting any definite chemotherapeutic regimen has been our institutional standard for the treatment of stage IV CRC throughout the past 20 years. This aggressive approach, aiming at the resection of the primary tumor was established by mutual consensus between the Departments of Surgery, Gastroenterology, and Medical Oncology at Ludwig-Maximilan University Munich. Nevertheless, it is obvious that not all patients treated in that way will profit to a comparable degree [9]. The present study sought to identify selection criteria which would help us to characterize those patients who might profit the most from such an aggressive surgical approach.

The current study population largely reflects an average population of all patients with stage IV CRC and non-resectable metastases. This notion is supported by the fact that 15% of all our patients with newly diagnosed CRC (233 patients out of 1,562) underwent elective primary tumor resection in the presence of a non-resectable metastatic disease. This number corresponds well to the published incidence of synchronous non-resectable metastases in CRC (14–16%) [4]. We feel that it was important to study such an unselected population of electively resected patients, since most of the published studies either analyzed subpopulations (symptom-free patients, rectal cancer only) [12, 14, 29, 31, 34, 36], or fairly heterogeneous populations combining stage IV CRC and locally advanced cancer [10, 16, 29–31, 33, 37], curable and non-curable stage IV CRC (e.g., resectable metastases) [4, 13, 34, 36, 38, 39], resective and non-resective procedures (e.g., bypass) [13, 16, 23, 29, 30, 37], non-resective operation and non-surgical therapy [16, 19, 32], or elective and emergency operations [4, 13, 19, 23, 28, 36]. Because of such different patient populations and study designs, it is hard to compare the results of those studies. It is further interesting that none of the mentioned studies have compared the two major entities, colon cancer and rectal cancer with respect to preoperative risk factors and postoperative course.

The distribution of primary tumor sites in our population reflected pretty much the general distribution of primary CRC within the large bowl [1, 2]. Therefore, stage IV CRC with synchronous non-resectable metastatic disease seems not to be specific for any location within the colorectum. There was no difference in demographics or preoperative risk profile between patients with colon and rectal cancer, and the vast majority of our patients were symptomatic in both groups. The latter appears notable, since several authors have described a significant subpopulation of asymptomatic patients, for which conservative treatment was advocated [18, 19, 22, 34]. Early symptoms were dominating in rectal cancer patients (rectal bleeding, irregular bowl habit), whereas late symptoms were preponderant in colon cancer patients (weight loss, pain). This difference might partly explain why local tumor growth was comparatively advanced in colon cancer patients of the present study (pT4, peritoneal carcinomatosis). We found a strong correlation between colon and rectal cancer regarding tumor differentiation, lymphatic spread, and metastatic disease. Hepatic metastases occurred at a nearly identical frequency and extent and were similarly distributed within the liver (Fig. 2). In summary, preoperative patient- and tumor-specific risk factors appeared similarly matched in both groups of patients.

In contrast, the major differences between colon cancer and rectal cancer patients became evident during the operative and postoperative course. Surgical resection of rectal cancer was mostly guided by oncological principles, whereas about one third of the colon cancer patients just underwent a tubular or segmental resection of the primary tumor. Those different surgical approaches might rather be the result of a different anatomical environment than of minor surgical accuracy, since negative resection margins (R0) could be obtained in both groups in a comparable number of patients. This finding appears essential, since local tumor clearance (R0), but not the type of operation (oncological vs. segmental) was found to be an independent predictor of postoperative survival. Loop enterostomy was not performed routinely but on the preference of the individual surgeon if the primary anastomosis was felt to be critical (e.g., due to colonic distension, marginal blood supply, intraoperative hemorrhage, carcinomatosis, R2 resection or significant weight loss). A substantial proportion of patients required an enterostomy. Stoma construction was predominantly performed in patients with rectal cancer (67.5%), and the probability of a secondary closure of the stoma was low (11.1%). This finding is remarkable, since loop enterostomies were performed in 35.1% of patients. Therefore, most of the “temporary” stomas were indeed permanent. However, the construction of a stoma was not associated with a reduction in surgical complication rates. Although we did not measure quality of life in stoma patients, we know from other publications that it might be reduced [40, 41].

The postoperative mortality was low in our population (4.7%), when compared to rates of 5–20%, which have been reported by others for palliative surgery in stage IV CRC [10, 13, 16–19, 28–30, 36, 38]. The considerably lower mortality of our cohort can most likely be attributed to the fact that we exclusively studied patients after elective operations, whereas the former studies included elective and emergency cases [13, 19, 28, 36] or non-resecting surgical procedures [16, 28, 30, 36]. Both variables are known to be associated with a high postoperative mortality. Our findings are in line with those by others who analyzed only highly selected patients (e.g., asymptomatic patients, liver secondaries only) and reported mortality rates as low as 0–3% [14, 31, 34]. Acute postoperative mortality of our populations correlated with age, ASA score, and postoperative complications, but was not dependent on the primary tumor site (colon/rectum).

Regardless of the comparatively low mortality rate in our study, postoperative morbidity was high in our cohort, but comparable to that reported by others [10, 28, 36, 42]. We found that following colonic surgery, general complications were dominating (29.5%), and that the frequency of surgical complications was within the normal range (19.9%) [10, 13, 14, 18, 30, 37]. Surgical complications were significantly more common after rectal surgery (40.3%). The anastomotic leakage rate amounted to 24.2% (including leakage of the Hartmann’s stump) and the total postoperative morbidity to 54.5%. Most of the leaks were incidental findings at regular postoperative endoscopy and did not require a reoperation (6.5%). However, it is well known that leakage after rectal surgery comes along with multiple outpatient visits and with long-term adverse effects such as anastomotic stenosis, functional outlet obstruction, or fistula formation [43]. Furthermore, leakage and other local complications might delay or even avert timely application of a palliative chemo- or chemo-radiation therapy, which has been shown to prolong survival of patients (Table 4) [20, 21]. We have found a significant association of surgical complication rate and the lack of a postoperative tumor-specific therapy in the present study. Palliative treatment regimens were administered less often in patients with surgical complications than in patients without (72.6% vs. 91.9%, p < 0.001).

Multivariate analysis revealed that primary rectal cancer was a highly significant and independent risk factor for postoperative surgical complications in stage IV CRC. Furthermore, the amount of liver metastases (>50% hepatic parenchymal replacement) and multiple comorbidities (in more than one organ) were independent predictors of postoperative surgical and non-surgical complications. Hepatic parenchymal replacement >50% was also associated with a reduced median survival time (7.9 months) and was identified by us and others to be the most significant independent prognostic factor for limited postoperative survival [12, 14, 16, 36, 38, 44]. Other measures of a large tumor burden such as high pT stage, positive lymph nodes, and positive resection margins as well as the lack of a postoperative chemo- or chemo-radiation therapy were also found to be independent predictors of a reduced survival time (Fig. 3). Those results correlate well with previous reports [19, 36, 37, 45].

Indication for an operation critically hinges on the question whether there are any true benefits to resecting the primary cancer or not. Patient selection must consider the anticipated live expectancy, the estimated risk of surgery, the availability of non-surgical alternatives for local palliation, and the impairment of quality of life that these treatments entail (e.g., avoidance of a stoma). For symptomatic colon cancer, particularly in cases with a right-sided cancer, there appears to be no reasonable alternative beyond an operation. On the other hand, our results suggest that patients with rectal cancer are poor candidates for palliative operations. Although rectal cancer is more likely to cause obstruction and bleeding than colon cancer [14], it is also well accessible for local tumor palliation through local excision, ablation (fulguration, laser therapy), argon beam application, radiation, and more recently through self-expanding metal stents in the middle and upper rectum [24, 25, 46–51]. Therefore, and particularly with respect to an early onset of a systemic therapy, the indication for elective surgery in stage IV rectal cancer should be more restrictive. As a consequence of our results, we have decided to exclude those patients with non-curable stage IV rectal cancer from elective operation, who present with locally advanced disease (pT4, expected R2 resection), or extensive comorbidity (more than one organ, ASA IV). In such high-risk rectal cancer patients, surgery is contraindicated, unless the tumor is immediately life-threatening. Furthermore, none of the patients with an extensive metastatic spread to the liver (hepatic parenchymal replacement >50%) should undergo elective primary tumor resection regardless of the tumor site (colon or rectum). In those patients, survival is short and postoperative complication rates are unacceptably high.

Of the present results, we cannot answer the question if elective palliative tumor resection entails any survival benefit for stage IV CRC patients. Future randomized controlled trials which might address this issue should therefore compare primary tumor resection with primary chemo- or chemo-radiation therapy (and later surgery only in case of intractable tumor complications), in a population of “non-emergency” patients in which surgery would not be the obligatory treatment.

Reference

Parkin DM (2001) Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol 2:533–543

Schmiegel W, Pox C, Adler G, Fleig W, Folsch UR, Fruhmorgen P, Graeven U, Hohenberger W, Holstege A, Junginger T, Kuhlbacher T, Porschen R, Propping P, Riemann JF, Sauer R, Sauerbruch T, Schmoll HJ, Zeitz M, Selbmann HK (2004) S3-Guidelines conference “colorectal carcinoma” 2004. Z Gastroenterol 42:1129–1177

Kleespies A, Fürst A, Jauch KW (2005) Stadieneinteilung kolorektaler Karzinome. In: Schölmerich J, Schmiegel W (eds) Leitfaden kolorektales Karzinom: Prophylaxe, Diagnostik Therapie. Uni-Med, Bremen, pp 74–85

Cook AD, Single R, McCahill LE (2005) Surgical resection of primary tumors in patients who present with stage IV colorectal cancer: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data, 1988 to 2000. Ann Surg Oncol 12:637–645

Mella J, Biffin A, Radcliffe AG, Stamatakis JD, Steele RJ (1997) Population-based audit of colorectal cancer management in two UK health regions. Colorectal Cancer Working Group, Royal College of Surgeons of England Clinical Epidemiology and Audit Unit. Br J Surg 84:1731–1736

Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, Valeanu A, Castaing D, Azoulay D, Giacchetti S, Paule B, Kunstlinger F, Ghemard O, Levi F, Bismuth H (2004) Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg 240:644–657

Martin R, Paty P, Fong Y, Grace A, Cohen A, DeMatteo R, Jarnagin W, Blumgart L (2003) Simultaneous liver and colorectal resections are safe for synchronous colorectal liver metastasis. J Am Coll Surg 197:233–241

Rodgers MS, McCall JL (2000) Surgery for colorectal liver metastases with hepatic lymph node involvement: a systematic review. Br J Surg 87:1142–1155

Kleespies A, Thiel M, Jauch KW, Hartl WH (2009) Perioperative fluid retention and clinical outcome in elective, high-risk colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 24(6):699–709

Joffe J, Gordon PH (1981) Palliative resection for colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 24:355–360

Longo WE, Ballantyne GH, Bilchik AJ, Modlin IM (1988) Advanced rectal cancer. What is the best palliation? Dis Colon Rectum 31:842–847

Nash GM, Saltz LB, Kemeny NE, Minsky B, Sharma S, Schwartz GK, Ilson DH, O'Reilly E, Kelsen DP, Nathanson DR, Weiser M, Guillem JG, Wong WD, Cohen AM, Paty PB (2002) Radical resection of rectal cancer primary tumor provides effective local therapy in patients with stage IV disease. Ann Surg Oncol 9:954–960

Rosen SA, Buell JF, Yoshida A, Kazsuba S, Hurst R, Michelassi F, Millis JM, Posner MC (2000) Initial presentation with stage IV colorectal cancer: how aggressive should we be? Arch Surg 135:530–534

Ruo L, Gougoutas C, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Cohen AM, Wong WD (2003) Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg 196:722–728

Tebbutt NC, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Hill ME, Tait D, Oates J, Livingston S, Andreyev J (2003) Intestinal complications after chemotherapy for patients with unresected primary colorectal cancer and synchronous metastases. Gut 52:568–573

Liu SK, Church JM, Lavery IC, Fazio VW (1997) Operation in patients with incurable colon cancer—is it worthwhile? Dis Colon Rectum 40:11–14

Sarela A, O'Riordain DS (2001) Rectal adenocarcinoma with liver metastases: management of the primary tumour. Br J Surg 88:163–164

Scoggins CR, Meszoely IM, Blanke CD, Beauchamp RD, Leach SD (1999) Nonoperative management of primary colorectal cancer in patients with stage IV disease. Ann Surg Oncol 6:651–657

Stelzner S, Hellmich G, Koch R, Ludwig K (2005) Factors predicting survival in stage IV colorectal carcinoma patients after palliative treatment: a multivariate analysis. J Surg Oncol 89:211–217

Simmonds PC (2000) Palliative chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ 321:531–535

Rougier P, Milan C, Lazorthes F, Fourtanier G, Partensky C, Baumel H, Faivre J (1995) Prospective study of prognostic factors in patients with unresected hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Fondation Francaise de Cancerologie Digestive. Br J Surg 82:1397–1400

Sarela AI, Guthrie JA, Seymour MT, Ride E, Guillou PJ, O'Riordain DS (2001) Non-operative management of the primary tumour in patients with incurable stage IV colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 88:1352–1356

Carne PW, Frye JN, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA (2004) Stents or open operation for palliation of colorectal cancer: a retrospective, cohort study of perioperative outcome and long-term survival. Dis Colon Rectum 47:1455–1461

Crane CH, Janjan NA, Abbruzzese JL, Curley S, Vauthey J, Sawaf HB, Dubrow R, Allen P, Ellis LM, Hoff P, Wolff RA, Lenzi R, Brown TD, Lynch P, Cleary K, Rich TA, Skibber J (2001) Effective pelvic symptom control using initial chemoradiation without colostomy in metastatic rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 49:107–116

Hunerbein M, Krause M, Moesta KT, Rau B, Schlag PM (2005) Palliation of malignant rectal obstruction with self-expanding metal stents. Surgery 137:42–47

van Hooft JE, Fockens P, Marinelli AW, Timmer R, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Bemelman WA (2008) Early closure of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgery for stage IV left-sided colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 40:184–191

UICC (2002) TNM-classification of malignant tumors. Wiley, New York

Boey J, Choi TK, Wong J, Ong GB (1981) Carcinoma of the colon and rectum with liver involvement. Surg Gynecol Obstet 153:864–868

Johnson WR, McDermott FT, Pihl E, Milne BJ, Price AB, Hughes ES (1981) Palliative operative management in rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 24:606–609

Makela J, Haukipuro K, Laitinen S, Kairaluoma MI (1990) Palliative operations for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 33:846–850

Moran MR, Rothenberger DA, Lahr CJ, Buls JG, Goldberg SM (1987) Palliation for rectal cancer. Resection? Anastomosis? Arch Surg 122:640–643

Konyalian VR, Rosing DK, Haukoos JS, Dixon MR, Sinow R, Bhaheetharan S, Stamos MJ, Kumar RR (2007) The role of primary tumour resection in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 9:430–437

Mahteme H, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, Graf W (1996) Prognosis after surgery in patients with incurable rectal cancer: a population-based study. Br J Surg 83:1116–1120

Benoist S, Pautrat K, Mitry E, Rougier P, Penna C, Nordlinger B (2005) Treatment strategy for patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable liver metastases. Br J Surg 92:1155–1160

Hurwitz H, Saini S (2006) Bevacizumab in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: safety profile and management of adverse events. Semin Oncol 33:S26–S34

Law WL, Chu KW (2006) Outcomes of resection of stage IV rectal cancer with mesorectal excision. J Surg Oncol 93:523–528

Law WL, Chan WF, Lee YM, Chu KW (2004) Non-curative surgery for colorectal cancer: critical appraisal of outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis 19:197–202

Kuo LJ, Leu SY, Liu MC, Jian JJ, Hongiun CS, Chen CM (2003) How aggressive should we be in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum 46:1646–1652

Chu QD, Davidson RS, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Wirtzfeld DA, Petrelli NJ (2002) Is abdominoperineal resection a good option for stage IV adenocarcinoma of the distal rectum? J Surg Oncol 81:3–7

Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Eckel R, Sauer H, Holzel D (2003) Quality of life in rectal cancer patients: a four-year prospective study. Ann Surg 238:203–213

Fucini C, Gattai R, Urena C, Bandettini L, Elbetti C (2008) Quality of life among five-year survivors after treatment for very low rectal cancer with or without a permanent abdominal stoma. Ann Surg Oncol 15:1099–1106

Al-Sanea N, Isbister WH (2004) Is palliative resection of the primary tumour, in the presence of advanced rectal cancer, a safe and useful technique for symptom control? ANZ J Surg 74:229–232

Weidenhagen R, Gruetzner KU, Wiecken T, Spelsberg F, Jauch KW (2008) Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a new method. Surg Endosc 22:1818–1825

Goslin R, Steele G Jr, Zamcheck N, Mayer R, MacIntyre J (1982) Factors influencing survival in patients with hepatic metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 25:749–754

Yamamura T, Tsukikawa S, Akaishi O, Tanaka K, Matsuoka H, Hanai A, Oikawa H, Ozasa T, Kikuchi K, Matsuzaki H, Yamaguchi S (1997) Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors of patients with unresectable synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 40:1425–1429

Fazio VW (2004) Indications and surgical alternatives for palliation of rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 8:262–265

Farouk R, Ratnaval CD, Monson JR, Lee PW (1997) Staged delivery of Nd:YAG laser therapy for palliation of advanced rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 40:156–160

Jakobs R, Miola J, Eickhoff A, Adamek HE, Riemann JF (2002) Endoscopic laser palliation for rectal cancer—therapeutic outcome and complications in eighty-three consecutive patients. Z Gastroenterol 40:551–556

Gevers AM, Macken E, Hiele M, Rutgeerts P (2000) Endoscopic laser therapy for palliation of patients with distal colorectal carcinoma: analysis of factors influencing long-term outcome. Gastrointest Endosc 51:580–585

Liberman H, Adams DR, Blatchford GJ, Ternent CA, Christensen MA, Thorson AG (2000) Clinical use of the self-expanding metallic stent in the management of colorectal cancer. Am J Surg 180:407–411

Khot UP, Lang AW, Murali K, Parker MC (2002) Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of colorectal stents. Br J Surg 89:1096–1102

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hans-Martin Hornung for data acquisition and management and Wolfgang H. Hartl for helpful discussion and critical revision of the manuscript (both from the Department of Surgery, University of Munich).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Financial support

Neither one of the authors nor the institutions from which the work originated have asked for, accepted, or received any direct or indirect financial support from a third party regarding the matter and materials discussed in this paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleespies, A., Füessl, K.E., Seeliger, H. et al. Determinants of morbidity and survival after elective non-curative resection of stage IV colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 24, 1097–1109 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-009-0734-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-009-0734-y