Abstract

Background and aims

Initial experience with the posterior sphincterotomy for treating anal fissures was unsatisfactory, with a significant rate of recurrences and anal incontinence. This report describes the lateral approach to complete section of the internal sphincter.

Patients and methods

Between 1997 and 2001 we surgically treated 164 patients for anal fissure. Preoperative and postoperative anal manometries were recorded. Postoperative course and early and long-term results were recorded.

Results

No fissure failed to heal. Early complications included bleeding, hematoma, and pain. A transient, variable degree of incontinence occurred in 15 patients and persistent incontinence to flatus and soiling in 5. After total sphincterotomy no long-term complication was observed. Patient satisfaction was 96%.

Conclusion

Total subcutaneous, internal sphincterotomy is a safe, effective procedure for the treatment of chronic anal fissure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Internal sphincterotomy was introduced for treating anal fissures in the 1950s [1]. Initial experience with the posterior sphincterotomy was unsatisfactory; the main weakness of this procedure was a significant rate of recurrences and anal incontinence and a long period required for the wound to heal [2]. Many of these drawbacks were overcome by the adoption of lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy [3, 4]. This procedure achieves a high degree of success despite persistence or recurrence of anal fissures, and deficiencies in anorectal continence have been reported to follow it [5, 6, 7, 8]. The incidence of these unfavorable outcomes has been reported to be related mostly to the height of the sphincterotomy, thus raising the question of the ideal length of the sphincteral section [9, 10]. Here we describe the technique and results of the complete section of the internal sphincter.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between January 1997 and December 2001 we treated 186 patients for chronic anal fissure who were nonresponders to medical therapy (glyceryl trinitrate 0.2% paste twice a day for 6 weeks) by lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy. Twenty-two patients were lost to follow-up and excluded. The remaining 164 patients were enrolled in the study (93 men, 71 women; mean age 37 years, range 18–44; Table 1). The fissure was on the posterior midline in 137 patients, anterior in 26, and both in one. The most common symptoms encountered in this series were pain (98.7%) and bright rectal bleeding (79.7%). An occasional undue expulsive force from a hard fecal mass was found in 40% of our patients. Discomfort with bowel movements was reported in all cases and constipation by 49 (30%).

The following data were recorded: age, sex, site of the fissure, symptoms and their duration, bowel habit, pre- and postoperative anal manometries, length of surgical procedure, postoperative continence index, patient satisfaction, minor and major complications, and long-term outcome. A chronic fissure was defined as a lesion that presented indurated edges, sentinel pile, hypertrophied anal papillae, and the presence of circular muscle fibers at the base of the cutaneous defect. Balloon manometry was performed in all patients preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively. Manometric assesments were performed, using an 8-lumen catheter perfused with sterile degassed water according to the technique described by Williams et al. [11].

Surgery

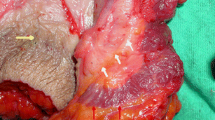

All patients were operated on by the first author. No laboratory tests and no enema were performed preoperatively. In all patients cardiac function and pulse oxymetry were monitored, and all had an intravenous access. With the patient in the prone jackknife position, the perineal region is prepared with a disinfectant solution and draped in the usual fashion. The left index finger is introduced into the rectum. The sphincter complex is explored and the point of the finger is placed within the anal canal in correspondence with the intersphincteral groove. With a 25-G needle an anesthetic solution of 10 cc of 0.5% xylocaine with adrenaline 1:200,000 is infiltrated into the left lateral aspect so that the anesthetic reaches the sphincter. A no.11 knife blade is then inserted to the lateral aspect of the anus with the blade oriented with the flat side parallel to the anal canal until the tip reaches the top of the finger; the sharp edge of the blade is then rotated medially (Fig. 1). By means of delicate strokes of the blade the internal sphincter is divided downward, as the top of the finger is progressively retracted. This exerts a cautious, gentle but firm direct pressure on the mucosa to ease the full-thickness division of the muscle yet avoiding breaching of anal mucosa and injury to the surgeon's finger (Fig. 2). As division is completed, a "give" on the sphincter can be palpated. A slight ooze of blood can be arrested quickly by digital compression and by plugging the surgical wound with a tranexanic acid-soaked gauze strip, which is removed within 48 h. Hypertrophied anal papillae and sentinel pile were routinely removed. Mean operative time was 7.2±1.4 min; there were no intraoperative complications. Patients were discharged within 1 h (mean 38±13 min) after surgery with prescription for a mild analgesic and instructions to consume a high-fiber diet.

Outcome measures and follow-up

The primary outcome measure was healing of the fissure, defined as its complete reepitelization. Secondary outcome measures were pain control, reduction in resting pressure, and anal continence. Review occurred daily within the first week at 4 weeks, and then at 3, 6, and 12 months. The mean follow-up was 30 months. Follow-up data were collected by personal interview and examination and were analyzed by the two senior authors (A.T., G.M.). Healing of the fissure was scored as complete, partial, or absent (recurrent or persistent). At the beginning of our experience, in 20 patients required completeness of internal sphincterotomy was verified by endoanal ultrasound 2 weeks after surgery. A questionnaire was administered to each patient 12 months after surgery, and all patients responded. Responses were analyzed. Satisfaction with the procedure was rated by patients as: very successful, moderately successful, or failure. Symptom improvement was rated as resolved completely, resolved but recurred, or unchanged. The continence was graded according to the score of Jorge and Wexner [12].

Early complications were defined as conditions present within 1 month following surgery that resolved spontaneously or with medical therapy (i.e., ecchymoses or hematoma, perianal abscess, fistula in ano, hemorrhage, and prolapsed thrombosed hemorrhoids). Long-term complications were defined as conditions that occurred after 1 month of surgery that required some type of corrective procedure (i.e., persistent prolapsed hemorrhoids, incontinence symptoms).

Results

Mean resting pressure before sphincterotomy was 90.3 mmHg (median 89 mmHg, 95% CI 89.04–91.53, range 71–107, SD 8.1, SEM 0.6), and 6 months after surgery was 48.6±4.3 mmHg (median 49 mmHg, 95%CI 47.89–49.23, range 41–58, SD 4.3, SEM 0.3; Wilcoxon test t=0.01, Z=11.10, P<0.001). No patient showed deficit of continence preoperatively; there was deficit of squeezing pressure in three women.

Early complications included immediate postoperative bleeding (n=2), ecchymosis (n=4), hematoma (n=1), and prolapsed thrombosed hemorrhoids (n=2). All surgical wounds had healed within the first week, and pain control was achieved in all patients. Early loss of continence to flatus and fecal soilage were observed in 15 patients (9.1%).

Complete continence was restored within 3 months in all but five cases, including three women with preoperative manometric findings of damage to the external sphincter. The difference between resting pressure at anal manometry in patients with and without continence problems did not reach statistical significance (43.4 vs. 49.3 mmHg, P=0.06). All fissures healed completely within 6 weeks, and symptoms were reported as completely resolved in all cases. Most patients in this series were very satisfied, except six who were only moderately satisfied because of low-grade anal incontinence (five cases) and prolonged postoperative pain caused by hematoma (n=1). No recurrent fissures were observed during follow-up. No patient judged the treatment a failure.

Discussion

An occasional undue expulsive force from a hard fecal mass occurring in chronic constipated patients has long been considered as the cause of anal fissure [13]. This finding, in 40% of our patients, confirms the outcome of other studies maintaining that anal fissures are frequent in patients with normal intestinal movements or even diarrheal stools [14]. An increased basal tone of the internal sphincter and an elevated resting pressure were the preoperative manometric findings in all of our patients. These anal pressure abnormalities have were considered primary events responsible for anal fissure in several earlier studies [15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Reducing sphincter tone should thus be considered the primary goal of any therapeutic measure for anal fissure. Both conservative and invasive methods have been employed for this purpose. Topical application of nitroglycerin ointment [20, 21] and injection of botulin toxin into the anal sphincter [22, 23] both significantly decreased maximum resting pressure. While following these procedures, however, recurrences are to be expected because the reduction in sphincteric tone is only temporary [24, 25, 26, 27]. Substantial long-term follow-up data are lacking. Among invasive procedures, sphincter stretching has been associated with a significant risk of incontinence while failure to relieve symptoms and persistence rates have been reported as high as 56% and 57%, respectively [28, 29]. Internal sphincterotomy is the surgical treatment for anal fissure. Because of unsatisfactory results [2] the posterior technique has been largely abandoned, with few exceptions, in favor of lateral sphincterotomy [30, 31]. The latter procedure may be performed under local or general anesthesia by either open or closed technique. The operation was performed in the current series under local anesthesia. Shortage of hospital beds and the increasing demand to containing sanitary costs makes this a paramount consideration. Furthermore, because voluntary closure of the anal canal brings about the contraction of both the voluntary and involuntary internal sphincter, if there is any question of defining the intersphincteral groove by palpation, under local anesthesia the patient may be asked to contract the sphincter, thus making clear the intersphincteral groove. Compared with the closed technique the open technique is awkward, time consuming, and associated with higher rates of complications and recurrences [32, 33].

The debate continues regarding how much of the internal sphincter should be divided [34, 35]. However, sphincterotomies that are too limited or too extended are predisposed to treatment failure and to anal incontinence, respectively. [36] The dentate line is the only reference when dividing the internal sphincter. While the need for endoscopic support affects the simplicity of the procedure, the digital detection of the proximal sphincteric edge is a precise, yet simply achieved, anatomical reference employed in the adopted technique. The total division of internal sphincter allows early healing, and consequent intramuscuar linear fibrosis prevents long-term incontinence. Furthermore, while the division of the mucosal lining enhances the rate of local septic complications, the goal of preserving the continuity of the intestinal lining is achieved easily.

The procedure adopted here is simple provided that the surgeon has some understanding of and experience with anal anatomy, which is achievable after a short training. Success of the procedure can be measured by the rates of unhealed or recurrent fissures, stub-wound-related complications, and disturbances of anal continence [37]. The procedure used in the current series was followed by a negligible overall complication rate and a very high degree of success in relieving pain, healing the fissure, and preventing recurrence. Long-term, major complications were observed in only 3.6% of patients whereas early complications in no more than 11.6% of patients. No patient complained of unhealed fissures or recurrences, and only five reported permanent disturbances of flatus and soiling. Three of these cases developed in pluriparae women who were all noted at preoperative rectal manometry to have external sphincteric defects, presumably due to obstetric trauma. These results emphasize that women with a presumptive prior history of obstetric trauma, and manometric finding of decreased squeeze pressure should be treated either with less division of the internal sphincter or by perianal skin flap advancement to reduce the risk of onset of disturbances of anal continence [38, 39, 40].

Conclusion

Because of the high degree of surgical success, patient satisfaction and the low rate of major morbidity the full-length section of the internal sphincter may be considered as a straightforward, safe, and effective treatment for anal fissure. Our results suggest as a lesser division of the internal sphincter or medical therapy should be performed in women with history of obstetric trauma. Therefore although further prospective trials are required to confirm our results, we strongly support this technique as the elective procedure in the treatment of anal fissure.

References

Eisenhammer S (1959) The evaluation of internal anal sphincterotomy operation with special reference to anal fissure. Surg Gynecol Obstet 109:583–590

Bennett RC, Goligher JC (1962) Results of internal sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Br J Surg 2:1500–1503

Notaras MJ (1971) The treatment of anal fissure by lateral subcutaneous internal sphincterotomy. A technique and results. Br J Surg 58:96–100

Sohn N, Weistein MA (1978) Acute anal fissure: treatment by lateral subcutaneous internal anal sphincterotomy. Am J Surg 136:277–278

Marby M, Alexander-Williams J, Buchmann P et al (1979) A randomized controlled trial to compare anal dilatation with lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 22:308–311

Nyam DC, Pemberton JH (1999) Long-term results of lateral internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: reference to incidence of faecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1306–1310

Pescatori M (1999) Soiling and recurrence after internal sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 42:687–688

Nelson RL (1999) Meta-analysis of operative techniques for fissure-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1424–1431

Argov S, Levandosky O (2000) Open lateral sphincterotomy is still the best treatment for chronic anal fissure. Am J Surg 179:201–202

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Bartram CI (1994) Prospective study of the extent of internal anal sphincter division during lateral sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 37:1031–1033

Xynos E, Tzortzinis A, Chrysos E, Tzovaras G, VassilakisJS (1993) Anal manometry in patients with fissure-in-ano before and after internal sphincterotomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 8:125–128

Jorge JMN, Wexner SD (1993) Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 36:77–97

Jensen SL (1988) Diet and other risk factors for fissure-in-ano: prospective case control study. Dis Colon Rectum 31:770–773

Kim D, Wong WD (1997) Anal fissure. In: Nicholls RJ, Dozois RR (eds) Surgery of the colon and rectum. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 233–44

Chowcat NL, Arajo JG, Boulos PB (1986) Internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure: long-term effects on anal pressure. Br J Surg 73:915–916

Schouten WR, Blankensteijn JD (1992) Ultra slow wave pressure variations in the anal canal before and after lateral internal sphincterotomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 7:115–118

Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJA (1994) Relationship between anal pressure and anodermal blood flow. Dis Colon Rectum 37:664–669

Sharp FR (1996) Patient selection and treatment modalities for chronic anal fissure. Am J Surg 171:512–515

Arabi Y, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MR (1977) Anal pressure in hemorrhoids and anal fissure. Am J Surg 134:608–610

Kennedy ML, Sowter S, Nguyen H, Lubowsky DZ (1999) Glyceryl trinitrate ointment for the treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of controlled trial and long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1000–1006

Richard CS, Gregoire R, Plewes EA et al (2000) Internal sphincterotomy is superior to topical nitroglycerin in the treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1048–1058

Lund JN (2000) Glyceryl trinitrate for anal fissures: patch or paste? Int J Colorectal Dis 15:246–247

Brisinda G, Maria G, Bentivoglio AR, Cassetta E, Gui D, Albanese A (1999) A comparison of injection of botulinum toxin and topical nitro glycerin for treatment of chronic anal fissure. N Engl J Med 341:65–69

Maria G, Brisinda G, Bentivoglio AR, Cassetta E, Gui D, Albanese A (1998) Botulinum toxin injections in the internal anal sphincter for the treatment of anal fissure: long-term results after two different dosage regimens. Ann Surg 228:664–669

Richard CS, Gregoire R, Plewes EA et al (2000) Internal sphincterotomy is superior to topical nitroglycerin in the treatment of chronic anal fissure: results of randomized, controlled trial by the Canadian Colorectal Surgical Trials Group. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1048–1057

Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, Milito G et al (2000) Glyceryl trinitrate for chronic anal fissure, healing or headache? Results of a multicenter randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Dis Colon Rectum 43:174–179

Hasegawa H, Radley S, Morton DG, Dorricott NJ, Campbell DJ, Keigley MR (2000) Audit of topical glyceryl trinitrate for treatment of fissure in ano. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 82:27–30

Palazzo FF, Kapur S, Steward M, Cullen PT (2000) Glyceryl trinitrate treatment of chronic fissure in ano: one year's experience with 0.5% GTN paste. J R Coll Surg Edinb 45:168–170

Speakman CT, Burnett SJ, Kamm MA, Bartram CI (1991) Sphincter injury after anal dilatation demonstrated by anal endosonography. Br J Surg 78:1429–1430

Nielsen MB, Rasmussen OO, Pedersen JF, Christiansen J (1993) Risk of sphincter damage and anal incontinence after anal dilatation for fissure in ano: an endosonographic study. Dis Colon Rectum 36:677–680

Di Castro A, Biancari F, D'Andrea V, Caviglia A (1997) Fissurectomy with posterior midline sphincterotomy and anoplasty (FPS) in the management of chronic anal fissures. Surg Today 27:975–978

Di Bella F, Blanco GF, Giordano M, Torelli I (1999) Our experience in internal medioposterior sphincterotomy with anoplasty. Minerva Chir 54:545–549

Nelson RL (1999) Meta-analysis of operative techniques for fissure-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1411–1418

Kortbeek JB, Langevin JM, Khoo RE, Heine JA (1992) Chronic fissure-in-ano: a randomized study comparing open and subcutaneous lateral internal sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 35:835–837

Usatoff V, Polglase AL (1995) The longer-term results of internal sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Aust N Z J Surg 65:576–579

Coller JA, Karuf RE (1990) Anal fissure. In: Fazio VW (ed) Current therapy in colon and rectal surgery. Decker, Burlington, pp 17–19

Littlejhon DRG, Newstead GL (1997) Tailored lateral sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 40:1139–1142

Jensen SL, Lund F, Nielsen OV, Tange G (1984) Lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy versus anal dilatation in the treatment of fissure in ano in outpatients: a prospective randomized study. BMJ 289:528–530

Sariev AA (1999) Acute anal fissure in puerperants. Vestn Khir Im II Grek 158:80–83

Zbar AP, Kmiot WA, Aslam M et al (1999) Use of vector volume manometry and endoanal magnetic resonance imaging in the adult female for assessment of anal sphincter dysfunction. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1411–1418

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tocchi, A., Mazzoni, G., Miccini, M. et al. Total lateral sphincterotomy for anal fissure. Int J Colorectal Dis 19, 245–249 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-003-0525-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-003-0525-9