Abstract

Background

Abusive head trauma (AHT) is the most serious injury inflicted to the nervous system of neonate an infant with a high incidence of disabilities. The authors present two cases in which the initial manifestations and neurologic status were misinterpreted and stress that clinical presentation and imaging can be variable and confuse the examiner.

Discussion

Subdural hemorrhage (SDH) in this age group raises high suspicion of non-accidental trauma but have been reported in other situations such as several bleeding disorders. Although rare, hematological diseases should be considered when other data of maltreatment are lacking.

Conclusion

Differential diagnosis is important to avoid underdiagnosing AHT and to prevent morbidity if a pre-existing hematological disease is misdiagnosed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Abusive head trauma (AHT) is the most severe form of injury to the nervous system on newborn and infants and may lead to permanent impairment of the immature brain, particularly vulnerable to hypoxic-ischemic and diffuse axonal injury. The incidence of AHT during the first year of life ranges from 24.6 to 38 per 100,000 person-years [1,2,3,4] and the mortality rate may reach 35% [4]. In addition, the incidence of disabilities was estimated in about 70% at 5 years post-injury [5]. These figures can be even more eloquent if one considers that many cases are unreported. AHT is a diagnosis of exclusion and the recognition of diseases that can mimic abusive trauma is of fundamental importance for neurosurgeons and pediatricians. The authors report, through two cases, different presentations that can lead to the suspicion of AHT and how to differentiate them from accidental trauma.

Case 1

A 9-month-old boy was taken to the emergency room by his young mother and her unemployed boyfriend. According to her, the boy fell out of the crib, cried inconsolably, and was only taken to a nearby emergency hospital a few hours later, after vomiting and presenting a generalized seizure. At admission, he was rated 11 on the pediatric GCS, was pale, had a bilateral subgaleal hematoma, and had bruises in the left parietal region and the neck. No retinal hemorrhage was reported.

A non-enhanced cranial CT scan with reconstruction showed several cranial fractures, including a depressed one on the right and a diastatic involving the sagittal and coronal sutures on the left, being the last in continuity with a hemorrhagic contusion in the frontal lobe (Fig. 1). Old posterior rib fractures were found at the lower thoracic cage on the right. No long bone fractures were noticed. On suspicion of abuse, the case was referred to the police authorities, and the mother ultimately confessed that her boyfriend had repeatedly hit the boy’s head against a wall. After stabilization of the clinical conditions, the patient underwent a repair of the dura mater, elevation skull fracture, and treatment of the orthopedic condition, being discharged 11 days later.

Case 1: a non-enhanced cranial CT with reconstruction showing voluminous and extensive subgaleal hematoma, depressed right parietal fracture (arrows in A and C), diastatic fracture in continuity with a hemorrhagic contusion in the left frontal lobe (arrow in B), another diastatic fracture involving the sagittal and coronal sutures on the left side (double arrow in C), surgical aspect (asterisk in D)

Case 2

A 5-month-old girl was taken to the emergency room by her parents due to traumatic brain injury after falling from the bed. The mother was in postpartum depression and was alone at home with her two children. The delivery history was not atypical and there was no family history of hematological diseases.

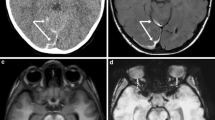

A CT scan was performed and showed perimedullary subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fig. 2). The child was hypoactive, but responsive and after conservative treatment for 1 week showed clinical improvement. MRI did not show other lesions. Upon investigation, fundoscopy was performed and was normal. Long bone X-rays were normal. Therefore, the mother underwent psychological monitoring, but no inappropriate family behavior was identified. In the absence of signs of aggression, a hematological investigation was performed, and the infant was diagnosed with type 1 Von Willebrand’s disease, justifying the atypical bleeding and excluding the hypothesis of aggression.

Discussion

Pediatric abusive head trauma (AHT) involves injury to the skull or intracranial contents of infants or children younger than 5 years, caused by inflicted blunt impact, violent shaking, or both [6]. Earlier nomenclature included whiplash shaken infant syndrome, shaken impact syndrome, inflicted childhood neurotrauma, and shaken baby syndrome. The current term (AHT) was adopted by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 2009 in recognition of the fact that head injury of children can involve a variety of biomechanical forces, including shaking, representing a complex medicolegal challenge [7, 8]. Compromise of the craniovertebral junction can also be associated.

The incidence of violent head trauma has been pointed out by recent studies carried out in Scotland, the USA, New Zealand, and Switzerland, ranging from 14.7 to 38.5 cases per 100,000 children, with the highest incidence for those under 1 year of age [6, 9,10,11,12]. It is noteworthy that, in the last survey carried out by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the incidence in the country was 0.76 fatal cases of AHT per 100,000 children up to 4 years of age, increasing to 2.14 when only children under 1 year of age were considered (6). In Brazil, there are still no studies that assess the real incidence of violent head trauma.

Although AHT often results in severe brain injury, the initial manifestations and neurologic status may be not recognized and even misinterpreted as “minor” trauma [13]. The clinical presentation can be wide and variable, but generally the cause–effect relationship of the trauma mechanism is poorly established. As we notice in the first case, the reported trauma history—a fall from a crib—was incompatible with the severity of the clinical findings and images obtained on admission.

Also, as in this case, perpetrators are often within the household, and the biological father is the aggressor in more than half of the cases, followed by a stepparent, and less frequently by the mother or both parents [14, 15]. The aggressor is usually a young male of low education and economic level, a member of a dysfunctional family, single or divorced, and a victim of parental violence as a child [16, 17]. Part or not of the family, perpetrators are usually emotionally immature and unable to cope with stressful situations such as crying, probably the most potent driving force in this setting. However, overt or latent, psychopathologies cannot be excluded as risk factors.

AHT is multifactorial, and at least one previous episode of shaking was admitted by family members in case 1, during the investigation. Therefore, it is not an isolated event, and there is a tendency to be repetitive with an increasing pattern of violence [1, 18]. A report in the literature describes that more than 25% of patients who are victims of AHT had sentinel symptoms not diagnosed by physicians, with bruises being the most common signs [19]. Bruising on the body are important warning signs and are known as “TEN-4” bruising (bruising of the torso, ears, and neck in children younger than 4 years or any bruising in an infant younger than 4 months) [20, 21].

Regarding imaging features, the classic triad, although not pathognomonic, has a high positive predictive value and consists of subdural hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, and long bone fracture [22].

Educational actions aimed at parents of newborns before hospital discharge and guidance for caregivers during the first months of the baby’s life can reduce the first occurrence of AHT, especially when the dangers of shaking are emphasized [10, 23]. Likewise, knowledge of the crying pattern in the baby’s first months of life helps to prevent new episodes, mainly if crying is recognized and accepted as a typical behavior in normal infants [24, 25].

Although not specific, subdural hemorrhages (SDHs) in locations such as interhemispheric or infratentorial spaces are more commonly related to AHT than to accidental trauma [26]. However, posttraumatic SDH has been reported in hemophilia A, B, and C; von Willebrand’s disease; fibrinogen disorders; thrombocytopenia; platelet disorders; hemolytic disease of the newborn; and rarely in other factor deficiencies (VII and X) [27]. Anderst et al. [27] described spontaneous SDH in bleeding disorders as severe hemophilia A and B and, type 1 von Willebrand’s disease. Although rare, hematological diseases should be considered when other data are lacking, as reported in case 2, in which the patient did not present retinal hemorrhage, fractures, skin bruising, or other signs of aggression. The atypical location of the hemorrhage can be explained by the underlying hematologic disease. Differential diagnosis is extremely important in these cases, both to avoid underdiagnosing AHT and to prevent morbidity if a pre-existing hematological disease is misdiagnosed.

Neurosurgeons should be aware of diseases that can mimic AHT, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, birth-related injuries, benign enlargement of subarachnoid spaces, and vascular malformations [22].

Conclusion

Abusive head trauma in children can present in different ways and understanding the history, social context, trauma mechanism, adequate imaging, and laboratory findings is essential for an accurate diagnosis. The lack of correct diagnosis is as serious in AHT as in other life-threatening diseases. Conditions mimicking AHT must be ruled out.

Data availability

The authors state that data are available under request.

References

Duhaime AC, Alario AJ, Lewander WJ et al (1992) Head injury in very young children: mechanisms, injury types, and ophthalmologic findings in 100 hospitalized patients younger than 2 years of age. Pediatrics 90(2 Pt 1):179–185

Duhaime AC (2008) Demographics of abusive head trauma. J Neurosurg Pediatr 1:349–50; discussion 350. https://doi.org/10.3171/PED/2008/1/5/349. PMID: 18447666

Kesler H, Dias MS, Shaffer M et al (2008) Demographics of abusive head trauma in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. J Neurosurg Pediatr 1:351–356. https://doi.org/10.3171/PED/2008/1/5/351. PMID: 18447667

Narang SK, Fingarson A, Lukefahr J (2020) AAP Council on Child Abuse and Neglect. Abusive head trauma in infants and children. Pediatrics 145:e20200203

Nuño M, Ugiliweneza B, Zepeda V et al (2018) Long-term impact of abusive head trauma in young children. Child Abuse Negl 85:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.011. Epub 2018 Aug 23 PMID: 30144952

CDC. Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect: a technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Accessed 30 Sept 2022, available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html

Choudhary AK (2021) The impact of the consensus statement on abusive head trauma in infants and young children. Pediatr Radiol 51(6):1076–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-020-04949-x. Epub 2021 May 17. PMID: 33999248; PMCID: PMC8126591

Barlow KM, Minns RA (2000) Annual incidence of shaken impact syndrome in young children. Lancet 356:1571–2

Dias MS, Smith K, DeGuehery K et al (2005) Preventing abusive head trauma among infants and young children: a hospital-based, parent education program. Pediatrics: e470–7. Available at: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/4/e470

Fanconi M, Lips U (2010) Shaken baby syndrome in Switzerland: results of a prospective follow-up study, 2002–2007. Eur J Pediatr 169:1023–1028

Keenan H, Runyan D (2001) Shaken baby syndrome: lethal inflicted traumatic brain injury in young children. N C Med J 62:345–348

Vinchon M (2017) Shaken baby syndrome: what certainty do we have? Childs Nerv Syst 33:1727–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3517-8. Epub 2017 Sep 6 PMID: 29149395

Scribano PV, Makoroff KL, Feldman KW et al (2013) Association of perpetrator relationship to abusive head trauma clinical outcomes. Child Abuse Negl 37:771–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.011. Epub 2013 Jun 2 PMID: 23735871

Notrica DM, Kirsch L, Misra S et al (2021) (2021) Evaluating abusive head trauma in children <5 years old: risk factors and the importance of the social history. J Pediatr Surg 56:390–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.10.019. Epub 2020 Oct 25 PMID: 33220974

Madigan S, Cyr C, Eirich R et al (2019) Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Dev Psychol 31:23–51

Rantanen H, Nieminen I, Kaunonen M et al (2022) Family Needs Checklist: development of a mobile application for parents with children to assess the risk for child maltreatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(16):9810. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169810. PMID:36011439;PMCID:PMC9408053

Deans KJ, Thackeray J, Groner JI et al (2014) Risk factors for recurrent injuries in victims of suspected non-accidental trauma: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr 14:217. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-217. PMID:25174531;PMCID:PMC4236666

Sheets LK, Leach ME, Koszewski IJ et al (2013) Sentinel injuries in infants evaluated for child physical abuse. Pediatrics 131:701–707

Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Aldridge S, O’Flynn J (2010) Bruising characteristics discriminating physical child abuse from accidental trauma 125:67–74

Wilson TA, Gospodarev V, Hendrix S et al (2021) Pediatric abusive head trauma: ThinkFirst national injury prevention foundation. Surg Neurol Int 19(12):526. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_194_2021. PMID:34754576;PMCID:PMC8571401

Sidpra J, Chhabda S, Oates AJ et al (2021) Abusive head trauma: neuroimaging mimics and diagnostic complexities. Pediatr Radiol 51:947–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-020-04940-6. Epub 2021 May 17 PMID: 33999237

Starling SP, Holden JR, Jenny C (1995) Abusive head trauma: the relationship of perpetrators to their victims. Pediatrics 95:259–262

Barr RG (2014) Crying as a trigger for abusive head trauma: a key to prevention. Pediatr Radiol 44(Suppl 4):S559–S564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-014-3100-3. Epub 2014 Dec 14 PMID: 25501727

Lopes NRL, Williams LCA (2018) Pediatric abusive head trauma prevention initiatives: a literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse 19:555–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016675479. Epub 2016 Nov 6 PMID: 27821497

Piteau SJ, Ward MG, Barrowman NJ et al (2012) Clinical and radiographic characteristics associated with abusive and nonabusive head trauma: a systematic review. Pediatrics 130:315–323

Vinchon M, Delestret I, DeFoort-Dhellemmes S et al (2010) Subdural hematoma in infants: can it occur spontaneously? Data from a prospective series and critical review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 26:1195–1205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-010-1105-2. Epub 2010 Feb 27 PMID: 20195617

Anderst JD, Carpenter SL, Abshire TC (2013) Section on Hematology/Oncology and Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Evaluation for bleeding disorders in suspected child abuse. Pediatrics 131:e1314–e1322. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0195. Epub 2013 Mar 25 PMID: 23530182

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by JFMS and TP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JFMS and TP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Protzenko, T., Salomão, J.F.M. Identifying abusive head trauma and its mimics: diagnostic nuances. Childs Nerv Syst 38, 2311–2315 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-023-05845-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-023-05845-z