Abstract

Intraparenchymal schwannomas of the brain are very rare, accounting for < 1% of intracranial schwannomas. We present a case of an 11-year-old boy with a left frontotemporal lobe schwannoma presented with seizure and neurogenic pulmonary edema. To our knowledge, this is the first case of intracerebral schwannoma with neurogenic pulmonary edema published to date and is the first case of an intracerebral schwannoma operated with fluorescein guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intracranial schwannomas consist 8% of all intracranial tumors predominantly arising from the cranial nerve sheath [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], whereas intraparenchymal schwannomas of the brain are very rare, accounting for < 1% of intracranial schwannomas [1,2,3,4].

Neurogenic pulmonary edema (NPE) is defined as a form of acute respiratory distress syndrome [8, 9]. An acute-onset (usually < 4 h) of pulmonary edema which occurs after a significant central nervous system injury is a characteristic for NPE [8,9,10,11,12,13]. A variety of central nervous system disorders including subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, intracranial hemorrhage, seizures, stroke, acute hydrocephalus, and arteriovenous malformation have been associated with NPE [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

We present a case of an 11-year-old boy with a left frontotemporal lobe schwannoma presented with seizure and neurogenic pulmonary edema. To our knowledge, this is the first case of intracerebral schwannoma with neurogenic pulmonary edema published to date. Also, this is the first case of intracerebral schwannoma operated with fluorescein guidance.

Case report

An 11-year-old right-handed boy admitted to emergency department with seizure. Patient was examined for the etiology of seizure by the emergency physicians. Non-contrast computed tomographic image of the brain revealed a large hypodense frontotemporal mass with extensive surrounding edema. Left lateral ventricular compression and midline shift were observed secondary to the size of the mass and accompanying edema. Patient had no relevant medical history, no known chronic disease, no history of febrile seizures, and no stigmata or a family history of neurofibromatosis.

Neurological examination revealed no focal neurological deficits and Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) was evaluated as 15 points. Physical examination revealed no pathological sign except the respiratory system. Respiratory system examination findings were bilateral crackles and subcostal and suprasternal retraction. He had a heart rate of 136 beats per minute, arterial pressure of 105/70 mmHg, respiratory rate of 42 ventilations per minute, and oxygen saturation of 89% without oxygen support and of 99% with oxygen support by facemask with a FiO2 of 60%. Chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse bilateral alveolar infiltration (Fig. 1).

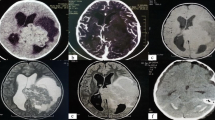

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient showed a mass lesion located in the left frontal lobe with frontal opercular extension and cystic formation with central necrosis (Fig. 2). Tumor was resected as gross total with the help of intravenous fluorescein application, via a left pterional approach. During surgery, patient underwent an intraoperative MRI scan (IO-MRI) in order to confirm the resection rate (Fig. 2). Fluorescein was useful to determine tumor borders easily in order to perform a meticulous dissection (Fig. 3, Video 1). Histopathological examination demonstrated verocay bodies, pericellular reticulin network, and areas of nuclear palisading confirming diagnosis of a schwannoma. Postoperative neurological examination was normal, and GCS was 15. Postoperative chest X-ray demonstrated a full recovery of alveolar infiltration (Fig. 1). Patient was discharged on the 4th postoperative day. At the 2-month follow-up, he was leading a normal life, was seizure-free, and had resumed going to school.

Upper row: contrast-enhanced axial and coronal T1-weigted magnetic resonance images revealed a mass lesion in the fronto-opercular region with peripheral contrast enhancement. FLAIR and T2-weigted images are demonstrating severe peripheral edema causing midline shift. Bottom row: contrast-enhanced axial and coronal T1-weigted, FLAIR, and T2-weigted intraoperative magnetic resonance scans demonstrating total removal of the tumor

Discussion

Here, we present our experience of an intracerebral schwannoma operated via fluorescein guidance. When the English literature was searched, we found fewer than 100 cases and thus our knowledge of this rare presentation is limited. In 1966, Gibson et al. operated the first reported case of a 6-year-old male patient with temporal lobe placement schwannoma [15]. According to the literature, intracerebral schwannomas appear more frequently than supratentorial, as opposed to the characteristic tumor location in the pediatric age group [4, 16, 17]. Although intraparenchymal schwannomas do not have characteristic radiological findings, cystic component, calcification, and peritumoral edema have been reported to accompany these lesions. Therefore, intraparenchymal schwannomas may be confused with neurothekeomas when evaluated with these radiological features [18].

It is well known that Schwann cells do not histologically exist in brain parenchyma. Therefore, the etiology of intracerebral schwannomas is still controversial. Several explanations have been offered this issue. Two theories that are classified as developmental and non-developmental might clarify this pathogenesis [19]. Ectopic migration of Schwann cells during embryogenesis by an unenlightened mechanism to brain parenchyma or possible proliferation of mesenchymal pial cells showing histological similarities in Schwann cells is evidence that supports the developmental theory [19]. On the other hand, the presence of Schwann cells in perivascular plexus around large arteries in subarachnoid space and brain parenchyma, and neoplastic process of these cells is the basis of non-developmental theory [19,20,21]. It is supported that intracerebral schwannomas tend to settle in the periventricular area and presence of perivascular nerve plexus in tela choroidea. In our case, we found that lesion was located in vascular-rich Sylvian fissure, around branches of the middle cerebral artery and pial surface was preserved. As our intraoperative video shows, fluorescein guidance was extremely helpful during dissection of tumor and determining the tumor borders. Our findings were considered to support non-developmental theory.

According to many sources, there are no definite criteria for the diagnosis of neurogenic pulmonary edema (NPE). NPE is generally diagnosed by chest X-ray, clinical examination, and exclusion of any primary pulmonary or cardiac lesion [8, 13, 14, 22]. Hence, the patient had no known pulmonary and cardiac dysfunction history to explain the chest X-ray findings, it was considered as neurogenic pulmonary edema. Although the pathophysiology of neurogenic pulmonary edema has not been strictly elucidated yet, we concluded that the ideal treatment method for our patient would be to eliminate the neurogenic event.

Conclusion

Although the association of NPE development with intracranial tumors is known, one of the well-known features of NPE is it’s acute development. In our case, we thought that intracranial mass was slowly growing, so we associated NPE with seizure. Intraparenchymal schwannomas are rare tumors and we have our current knowledge on this subject as a result of case reports. Also, we recommend fluorescein guidance for removal of intracerebral schwannomas; hence, it helped the surgeon during dissection of tumor and determining the tumor borders.

References

Alayyaf M, Taher Nasir N (2019) Seizures and blurred vision as initial presentation of intracerebral schwannoma: a rare tumor of the brain. Case Rep Pathol 2019:8158950. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8158950

Aryanpur J, Long DM (1988) Schwannoma of the medulla oblongata. Case report. J Neurosurg 69:446–449. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1988.69.3.0446

Menkü A, Oktem IS, Kontaş O, Akdemir H (2009) Atypical intracerebral schwannoma mimicking glial tumor: case report. Turk Neurosurg 19:82–85

Gao Y, Qin Z, Li D, Yu W, Sun L, Liu N, Zhao C, Zhang B, Hu Y, Sun D, Jin X (2018) Intracerebral schwannoma: a case report and literature review. Oncol Lett 16:2501–2510. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.8949

Scott WW, Koral K, Margraf LR, Klesse L, Sacco DJ, Weprin BE (2013) Intracerebral schwannomas: a rare disease with varying natural history. J Neurosurg Pediatr 12:6–12. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.3.PEDS12162

Srinivas R, Krupashankar D, Shasi V (2013) Intracerebral schwannoma in a 16-year-old girl: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Neurol Med 2013:171494. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/171494

Vaishya S, Sharma MS (2004) Frontal intraparenchymal schwannoma: an unusual presentation. Childs Nerv Syst 20:247–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-003-0852-8

Finsterer J (2019) Neurological perspectives of neurogenic pulmonary edema. Eur Neurol 81:94–102. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500139

Busl KM, Bleck TP (2015) Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Crit Care Med 43:1710–1715. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001101

Bahloul M, Chaari AN, Kallel H, Khabir A, Ayadi A, Charfeddine H, Hergafi L, Chaari AD, Chelly HE, Ben Hamida C, Rekik N, Bouaziz M (2006) Neurogenic pulmonary edema due to traumatic brain injury: evidence of cardiac dysfunction. Am J Crit Care 15:462–470

Cruz AS, Menezes S, Silva M (2016) Neurogenic pulmonary edema due to ventriculo-atrial shunt dysfunction: a case report. Braz J Anesthesiol 66:200–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2013.10.009

Sacher DC, Yoo EJ (2018) Recurrent acute neurogenic pulmonary edema after uncontrolled seizures. Case Rep Pulmonol 2018:3483282. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3483282

Mahdavi Y, Surges R, Nikoubashman O, Olaciregui Dague K, Brokmann JC, Willmes K, Wiesmann M, Schulz JB, Matz O (2019) Neurogenic pulmonary edema following seizures: a retrospective computed tomography study. Epilepsy Behav 94:112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.02.006

July M, Williamson JE, Lolo D (2014) Neurogenic pulmonary edema following non-status epileptic seizure. Am J Med 127:e9–e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.019

Gibson AA, Hendrick EB, Conen PE (1966) Case reports. Intracerebral schwannoma Report of a case. J Neurosurg 24:552–557. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1966.24.2.0552

Lee S, Park S-H, Chung CK (2013) Supratentorial intracerebral schwannoma : its fate and proper management. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 54:340–343. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2013.54.4.340

Erongun U, Ozkal E, Acar O, Uygun A, Kocaoğullar Y, Güngör S (1996) Intracerebral schwannoma: case report and review. Neurosurg Rev 19:269–274

Bulduk EB, Aslan A, Öcal Ö, Kaymaz AM (2016) Neurothekeoma in the middle cranial fossa as a rare location: case report and literature review. Neurochirurgie 62:336–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.07.003

Casadei GP, Komori T, Scheithauer BW, Miller GM, Parisi JE, Kelly PJ (1993) Intracranial parenchymal schwannoma. A clinicopathological and neuroimaging study of nine cases. J Neurosurg 79:217–222. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1993.79.2.0217

Jung JM, Shin HJ, Chi JG, Park IS, Kim ES, Han JW (1995) Malignant intraventricular schwannoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 82:121–124. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1995.82.1.0121

Guha D, Kiehl T-R, Krings T, Valiante TA (2012) Intracerebral schwannoma presenting as classic temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosurg 117:136–140. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.3.JNS111043

Romero Osorio OM, Abaunza Camacho JF, Sandoval Briceño D, Lasalvia P, Narino Gonzalez D (2018) Postictal neurogenic pulmonary edema: case report and brief literature review. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep 9:49–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebcr.2017.09.003

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

Excision of the intracerebral schwannoma with fluorescein guidance. (MP4 144,421 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gulsuna, B., Turkmen, T., Borcek, A.O. et al. Fluorescein-guided excision of a pediatric intraparenchymal schwannoma presenting with seizure and neurogenic pulmonary edema. Childs Nerv Syst 36, 1075–1078 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04438-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04438-z