Abstract

Background

Rhabdoid tumors are highly malignant tumors predominantly affecting the pediatric population. When these tumors occur outside of the kidneys, they are referred to as malignant extrarenal rhabdoid tumors (MERT), a rare highly aggressive subtype. Less commonly, these tumors involve the neuro-axis.

Objective

Here we present a case of a 15-year-old girl with intradural MERT of the lumbosacral spine who presented with back pain, sudden worsening of lower extremity strength, and complete loss of bowel and bladder control.

Results

The patient’s tumor showed loss of INI-1 and negative staining for cytokeratin AE1AE3, CD99, and SOX10.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, there are no previous case reports of MERT with intradural lumbosacral spinal involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Case report

Malignant rhabdoid tumors are solid highly aggressive tumors of childhood most commonly presenting in the kidneys [1, 2]. These tumors are rapidly growing; painful masses occurring most frequently in children less than 1 year of age, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% [3,4,5]. When these tumors occur in the soft tissue outside of the renal system, they are referred to as malignant extrarenal rhabdoid tumors (MERTs), a rare subtype that portends a grim prognosis [6, 7]. MERTs, unlike rhabdoid tumors, have been found most commonly in the late adolescent and young adult population [6, 7]. MERTs have been described throughout the body including the paravertebral muscles, liver, heart, chest wall, neck, and abdominal wall [5].

We present a case of a 15-year-old girl with an intradural malignant extrarenal rhabdoid tumor of the lumbosacral spine. There are a limited number of cases reported in the literature describing MERTs in the spine and paraspinal region [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an intradural lumbosacral malignant extrarenal rhabdoid tumor.

History/exam

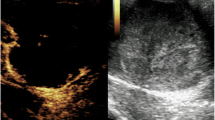

This is a case of a 15-year-old girl with past medical history of Celiac disease and attention deficit disorder who presented with back pain, sudden worsening of lower extremity strength, and complete loss of bowel and bladder control. Per the patient and her mother, the patient had been experiencing bilateral lower extremity weakness and numbness for 3 months, difficulty evacuating stool for approximately 3 months, several episodes of urinary/fecal incontinence for 1 week, and 30 lb weight loss over the past 3 months. The patient’s symptoms began as decreased sensation in her bilateral feet 3 months ago which progressed to her bilateral calves. This was followed by progressive difficulty with ambulation and maintaining urinary/fecal continence. The patient underwent an emergent MRI cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine which revealed a 14 cm × 3 cm × 3.7 cm intradural lumbosacral mass extending primarily to the left S1–S3 neural foramina to the sacral plexus and presacral region (Fig. 1). Given the patient’s clinical decline and radiological findings, the patient was taken emergently to the operating room for surgical decompression and debulking of the tumor.

Pre-operative MRI lumbar spine T1 FLAIR (row 1), T1 with contrast (row 2), and T2 (row 3). Midsagittal (column A) and left parasagittal (column B) views depicting lumbosacral mass extending through the left S1 and S2 foramina. Axial view of lumbosacral spine at the level of L4 (column C), L5/S1 (column D), and S1 (column E)

Operation

A midline lumbar incision was made and L3–L5 laminectomy was performed. The underlying dura was found to be extremely tense. Immediately upon opening the dura with an 11 blade, soft, gray friable tumor emanated through the incision under high pressure. The CUSA was brought into the field and used to centrally debulk the tumor. Neuromonitoring was used throughout the operation, and the nerve roots required significantly higher parameters to stimulate. Signals remained at their baseline throughout the procedure. Once approximately 50% of the tumor was resected and the cauda equina was sufficiently decompressed, it was decided to conclude the operation as the goals of the procedure had been achieved.

Pathological findings

Tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin and partially positive for actin. The tumor cells were negative for INI-1, SOX10, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, and CD99. There were approximately 23 mitoses per 10 high-power fields and approximately 15% necrosis (Fig. 2).

Postoperative course

Postoperatively, the patient’s motor exam improved to that of ambulating with minimal assist by postoperative day 7. Physical therapy and physical medicine and rehab worked with the patient and felt that the patient had progressed well and did not require inpatient rehab. Hematology/oncology was consulted immediately postoperatively to evaluate the patient. Their workup and body PET scan did not reveal further spread of the tumor from lumbosacral spine and paraspinal areas. The patient at the time of this publication was beginning therapy with hematology/oncology.

Discussion

Malignant rhabdoid tumor (MRT) was first believed to be a rhabdomyosarcomatoid variant of Wilms tumor with a poorer prognosis [1, 4]. Over time, MRT was further defined and understood to be separate from Wilms tumor and rhabdomyosarcoma [8]. When MRT occurs outside of the renal system, it is referred to as MERT. MERT has an older age of tumor onset but a more grim prognosis than that of MRT [4, 6, 7]. Specific data on 5-year survival is not available due to the rarity of MERT [4].

In this case, based on the patient’s history of 30 lb weight loss, location of the tumor, and MRI findings, our initial differential diagnosis included malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), sarcoma, and plexiform neurofibroma. MPNST was highest on the differential due to the weight loss, rapid progression of symptoms, and foraminal widening caused by the tumor on MRI.

The classic rhabdoid cells found on the pathology of rhabdoid tumors are not pathognomonic and may occur in a variety of tumors including sarcomas, carcinomas, and meningiomas [8]. MERTs are defined as having loss of INI-1, but this may also occur in epithelioid MPNST and epithelioid sarcoma.

This patient’s tumor had loss of INI-1. Negative staining for INI-1 is a characteristic of MERT but not unique to it. Negative staining for cytokeratin AE1AE3 and CD99 ruled out epithelioid sarcoma. Negative staining for SOX10 ruled out MPNST. This tumor was thus most consistent with MERT given its pathology profile and clinical picture.

Based on the imaging and progression of the patient’s symptoms over time, the tumor likely originated from the paraspinal region and quickly spread via the sacral neural foramina to the spinal canal and then along the nerve roots intradurally. Once the tumor passed a critical mass, the patient became symptomatic; first with urinary and fecal incontinence. Over time, the mass continued to grow and extend rostral leading to the patient’s sudden paraparesis.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of an intradural lumbosacral MERT. This is a rare entity and need not be at the top of a differential diagnosis, but proper workup for a patient with symptoms suggestive of a mass lesion in the intradural space should ultimately yield the diagnosis in a timely fashion.

Disclosure of funding

None

References

Beckwith JB, Palmer NF (1978) Histopathology and prognosis of Wilms tumors: results from the first National Wilms’ tumor study. Cancer 41:1937–1948

Wick MR, Ritter JH, Dehner LP (1995) Malignant rhabdoid tumors: a clinicopathologic review and conceptual discussion. Semin Diagn Pathol 12:233–248

Chung CJ, Lorenzo R, Rayder S, Schemankewitz E, Guy CD, Cutting J, Munden M (1995) Rhabdoid tumors of the kidney in children: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 164:697–700

Abdullah A, Patel Y, Lewis TJ, Elsamaloty H, Strobel S (2010) Extrarenal malignant rhabdoid tumors: radiologic findings with histopathologic correlation. Cancer Imaging 10:97–101

Oda Y, Tsuneyoshi M (2006) Extrarenal rhabdoid tumors of soft tissue: clinicopathological and molecular genetic review and distinction from other soft-tissue sarcomas with rhabdoid features. Pathol Int 56:287–295

Parham DM, Weeks DA, Beckwith JB (1994) The clinicopathologic spectrum of putative extrarenal rhabdoid tumors. An analysis of 42 cases studied with immunohistochemistry or electron microscopy. Am J Surg Pathol 18:1010–1029

Kodet R, Newton WA, Sachs N, Hamoudi AB, Raney RB, Asmar L, Gehan EA (1991) Rhabdoid tumors of soft tissues: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases enrolled on the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. Hum Pathol 22:674–684

Dobbs MD, Correa H, Schwartz HS, Kan JH (2011) Extrarenal rhabdoid tumor mimicking a sacral peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Skelet Radiol 40:1363–1368

Fridley JS, Chamoun RB, Whitehead WE, Curry DJ, Luerssen TG, Adesina A, Jea A (2009) Malignant rhabdoid tumor of the spine in an infant: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 45:237–243

Horie H, Etoh T, Maie M (1992) Cytogenetic characteristics of a malignant rhabdoid tumor arising from the paravertebral region. A case report. Acta Pathol Jpn 42:460–465

Robbens C, Vanwyck R, Wilms G, Sciot R, Debiec-Rychter M (2007) An extrarenal rhabdoid tumor of the cervical spine with bony involvement. Skelet Radiol 36:341–345

Robson DB, Akbarnia BA, deMello D, Connors RH, Crafts DC (1987) Malignant rhabdoid tumor of the thoracic spine. Case report Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 12:620–624

Tang Y, Li S, Qu J, Zhou Y, Xiao J (2015) Malignant Rhabdoid tumor with cervical vertebra involvement in a teenage child: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 50:173–178

Singla N, Kapoor A, Chatterjee D, Radotra BD (2016) Ultra early recurrence in giant congenital malignant rhabdoid tumor of spine. Childs Nerv Syst 32:2471–2474

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Patient consent

Obtained from parents and available upon request

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garling, R.J., Singh, R., Harris, C. et al. Intradural lumbosacral malignant extrarenal rhabdoid tumor: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 34, 165–167 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3571-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3571-2