Abstract

Background

The goal of this review was to identify the safety and medical care issues that surround the management of patients who had previously undergone medical care through tourism medicine. Medical tourism in plastic surgery occurs via three main referral patterns: macrotourism, in which a patient receives treatments abroad; microtourism, in which a patient undergoes a procedure by a distant plastic surgeon but requires postoperative and/or long-term management by a local plastic surgeon; and specialty tourism, in which a patient receives plastic surgery from a non-plastic surgeon.

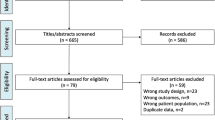

Methods

The ethical practice guidelines of the American Medical Association, International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, and American Board of Plastic Surgeons were reviewed with respect to patient care and the practice of medical tourism.

Conclusions

Safe and responsible care should start prior to surgery, with communication and postoperative planning between the treating physician and the accepting physician. Complications can arise at any time; however, it is the duty and ethical responsibility of plastic surgeons to prevent unnecessary complications following tourism medicine by adequately counseling patients, defining perioperative treatment protocols, and reporting complications to regional and specialty-specific governing bodies.

Level of Evidence V

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors www.springer.com/00266.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medical tourism continues to evolve into a global healthcare phenomenon, with an excess of 1.3 million Americans undergoing procedures abroad yearly. Perhaps more striking is the $600 million spent on medical treatments outside of the United States, an amount that has grown 13 % from 2004 to 2009. The projected increase in outbound medical tourists from 750000 in 2007 to 15.75 million in 2017 represents $30.3–79.5 billion spent overseas for medical care, which ultimately represents a lost opportunity cost to domestic healthcare providers of $228.5–599.5 billion [1]. The medical tourism industry has combined financial productivity with patient-driven healthcare, frequently through the incentive of vacation-based packages [2, 3].

Health insurance companies such as Aetna, Blue Cross/Blue Shield of South Carolina, Blue Shield of California, and United Group Programs are beginning to reimburse for some out-of-the-country treatments such as heart valve replacement and angioplasties; however, the majority of medical insurance carriers do not reimburse medical care that is performed on an elective basis outside of the US or for direct postoperative sequelae related to any care performed in such a manner [4]. This means that the financial reserves of patients undergoing reconstructive or aesthetic-based plastic surgery procedures are frequently exhausted at the time of postoperative consultation, leaving little for the possible management of complications or revisions.

Many plastic surgeons may be unwilling to care for these patients postoperatively when there are poor outcomes because of large expenditures of time with minimal reimbursement, or even possible litigious complications. Also, it may seem to be acceptable to redirect care to another colleague or emergency room; however, tourism patients are often in need of expedient and safe care to optimize outcomes and prevent further morbidity. There are numerous ethical guidelines for medical tourism that pertain to patient exploitation, novel locations, and the reliability or safety of advertised medical procedures. However, medical tourism guidelines are discussed predominantly from the perspective of the patient, and broadly touch upon overarching ethical concepts such as patient autonomy, principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. The International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) provides “key guidelines for plastic surgery travelers,” with aftercare/complications briefly mentioned. Unfortunately, these guidelines pose questions only to the patient and provide little information about safe and ethical standards for care: “What doctor will care for you at home if you have complications and who will pay for secondary or revision procedures?” [5].

The goal of this article was to specifically discuss the ethics and safety of medical tourism as they relate to the field of plastic surgery and the physicians who are challenged with managing these patients postoperatively. This is germane to plastic surgery practitioners who have consultations with patients who have undergone foreign medical tourism, or in the event of dissatisfaction and management of patients with “plastic surgery” procedures performed by a physician untrained in plastic surgery or a noncolleague plastic surgeon. The appropriate guidelines for accepting or undertaking care of a patient following tourism-type surgery is discussed and suggestions to both assist the physician and optimize patient care are offered.

Current Professional Guidelines

The ethical practice guidelines and Codes of Ethics of the American Medical Association (AMA), ISAPS, American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), and American Board of Plastic Surgeons (ABPS) were reviewed with respect to patient care and the practice of medical tourism. Codes of Ethics have been created by both the ABPS and the ASPS that contain general principles for the foundation of ethical practice of medicine and plastic surgery as a whole. However, when it is appropriate to “manage” the routine postoperative care of a patient who has been treated by another surgeon is unclear [6, 7]. The ABPS Code of Ethics specifies that “physicians should merit the confidence of patients entrusted to their care, rendering to each a full measure of service and devotion” (Section 2, I). This focus on service is also emphasized in the ABPS mission statement that explicitly states: “the mission of The American Board of Plastic Surgery, Inc. is to promote safe, ethical, efficacious plastic surgery to the public” (Section 1, II). However, supporting unsafe surgical practice at home or abroad conflicts with this mission.

In addition, the Code of Ethics repeatedly emphasizes that the plastic surgeon must not work from self-interest or in the interest of any one individual patient, but for the benefit of society as a whole: “The honored ideals of the medical profession imply that the responsibilities of the physician extend not only to the individual but also to society. Activities, which have the purpose of improving both the health and well being of the individual and the community, deserve the interest and participation of the physician” (Section 2, III). Such statements, when applied to the safety and ethics of caring for a patient who is referred, by either the primary surgeon or self-referred, after undergoing medical tourism complications broadly imply that the plastic surgeon is ethically driven to care for these patients out of a sense of service. The ASPS Code of Ethics echoes the statements of the ABPS Code regarding the duty of the plastic surgeon to care for patients entrusted to them for the individual patient’s benefit and for that of society as a whole, since “the principal objective of the medical profession is to render services to humanity with full respect for human dignity,” and “the honored ideals of the medical profession imply that the responsibilities of the physician extend not only to the individual, but also to society” (Section 1, II, X).

Despite both the ABPS and the ASPS Codes of Ethics emphasizing the importance of the plastic surgeon to serve patients and the public as a whole, the realities of the complications that result from overseas or domestic medical tourism often place an incredible burden and ethical dilemma on the plastic surgeon to whom the care of these patients is entrusted [8]. Interestingly, neither the ABPS nor the ASPS Code directly addresses medical tourism. The ASPS Code, however, does have two statements that may be directly applied to the care of the medical tourist patient. Section 1, article V explicitly states: “Physicians may choose whom to serve. In emergency situations, however, physicians should render service to the best of their ability.” The “emergency situation” is a potential gray area for the medical tourism patient who presents to a new plastic surgeon’s office. An extruding breast implant originally placed in Mexico with an active infection and objective signs of sepsis would certainly qualify as an “emergency situation,” but the spectrum from overfilled subglandular implants to symmastia or severe capsular contracture is increasingly more difficult to manage, especially if the etiology of the complication is directly due to some element of negligence or lack of training on the part of the previous surgeon.

The AMA provides guidelines on general medical tourism addressed to employers, insurance companies, and other entities that facilitate or incentivize medical care outside the US, advocating that “patients should only be referred for medical care to institutions that have been accredited by recognized international accrediting bodies (such as the Joint Commission International or the International Society for Quality in Health Care), prior to travel local follow-up care should be coordinated and financing should be arranged to ensure continuity of care when patients return from medical care outside the US, and insurance coverage for travel outside the US for medical care must include the costs of necessary follow-up care upon return to the US” [9]. Unfortunately, even these guidelines remain largely inapplicable for plastic surgery patients following elective cosmetic procedures and, therefore, providers are not obligated to ensure follow-up care.

Ultimately, while the ABPS, ASPS, and AMA have all put forth guidelines and Codes of Ethics regarding ethical care of patients, none of the current professional guidelines adequately guide the patient or the providing plastic surgeon. As a result, we offer a set of guidelines and recommendations following a more specific discussion of the challenges that macro-, micro-, and specialty medical tourism pose for the plastic surgeon as outlined in Table 1.

Macro-Medical Tourism

Data regarding the safety of plastic surgery macro-medical tourism and complications from international surgery tourism are limited. Birch et al. [10] distributed an 11-question survey to 65 National Health Service (NHS) consultations and 11 NHS plastic surgical units in the UK and from the responses concluded that when plastic surgery patients travel abroad for procedures, the most common areas operated on are the breasts and the abdomen (76 %). Not surprisingly then, abdominoplasty, breast augmentation, and breast reduction accounted for 60 % of the complications seen upon the patients’ return [10], and incredibly only a minority (26 %) of patients had made any follow-up arrangements for after their surgeries. Of the complications found in the analysis by Birch et al. [10] 53 % were seen in the emergency room, with 66 % requiring inpatient admission and 70 % requiring corrective surgery. This study concludes that the NHS has “a duty of care to anyone that presents with such problems as infections, wound breakdown or haematomas,” but it does not give guidelines on caring for revision procedures. The study noted that patients may not return to their original international plastic surgeon because of a lack of access or they had lost faith in the original surgeon/organization who operated on them. In this setting, if postoperative arrangements had been discussed with the local or secondary plastic surgeon prior to travelling abroad, presumably a large amount of time and expense could have been obviated by timely specialist care (Fig. 1). Social factors such as family support and previous or family experience with a plastic surgeon can influence this decision [11]. A clinical example of this phenomenon occurred when a 57-year-old patient presented with fulminant mastitis and draining abscess following breast implant explantation and mastopexy, despite a similarly disastrous complication with her daughter’s breast augmentation by the same surgeon (Fig. 2).

A 34-year-old patient presented for revision breast surgery after three previous augmentation mammaplasty operations and revisions in South America that failed due to infection, severe capsular contracture, and implant exposure. At presentation there was a subglandular implant on the right and a contracted breast without an implant on the left (patient consent was obtained for the use of her images)

A 57-year-old patient presented 6 weeks following bilateral breast implant explantation and mastopexy. At the time of presentation, there was fulminant mastitis with fat necrosis and a draining abscess. Of note, she is the mother of the patient in Fig. 1 and returned to the same South American surgeon despite several complications (patient consent was obtained for the use of her images)

The largest US survey that analyzed the complications of medical tourism with respect to plastic surgery was performed by Melendez et al. [3], who distributed a 15-question survey to active ASPS members and got 368 responses. The majority of medical tourism patients seeking postoperative care for a complication from a secondary surgeon were self-referred via the emergency room (a finding also noted by Birch et al. [10]), and originally underwent either breast augmentation or body-contouring procedures. Of these patients, more than half required multiple operations, and at least one patient required more than a month of hospitalization in a surgical ICU.

The element of macro-medical tourism highlights the secondary ethical dilemma with these patients, namely, appropriate billing and compensation practices. In the study by Melendez et al. [3], compensation for the secondary management of medical tourism complications was found to be highly variable. This may strengthen the argument that complications of an increasingly disastrous nature should be directly linked to increasing out-of-pocket compensations; however, a thorough and well-documented discussion about patient expectations and the need for additional interventions should be candidly developed in the initial consultation. This way, high costs that are not intended to be prohibitive to care but simply reflective of the level of technical expertise to correct the complication or continued care are better understood by the patient. In the initial consultation, the surgeon should also discuss the consultation fee and outline the financial responsibilities associated with postoperative visits, and in the case of secondary revisions or emergencies, the operative or possible anesthesia/hospital fees. Thus, the patient can better evaluate her budget to determine the possible overall price of the tourism-type procedure and be financially prepared for unexpected outcomes.

In addition, patients may view secondary revisions or salvage procedures as “reconstructive” in that they are attempting to fix what would otherwise be considered a secondarily acquired deformity. Frequently, patients engage in tourism medicine for financial reasons, and the typical consultation or revision charges can be seen as exorbitant or inappropriate given the “apparent” need for an improved appearance. However, despite a poor aesthetic outcome, since the primary surgery was a fee-for-service elective procedure, revisions are rarely, it ever, covered by insurance. Patients who present for management or consultation following failed tourism plastic surgery should be billed as other cosmetic, nonreconstructive surgery patients.

Micro-Medical Tourism

The second statement of the ASPS Code relevant to medical tourist patients is Section 2, Article I (J), which asserts that “each member may be subject to disciplinary action, including expulsion, if the member performs a surgical operation or operations (except on patients whose chances of recovery would be prejudiced by removal to another hospital) under circumstances in which the responsibility for diagnosis or care of the patient is delegated to another who is not qualified to undertake it.” This is certainly relevant for the plastic surgeon that engages in domestic micro-tourism, wherein a patient operated on in one city seeks postoperative care and follow-up in a different city with a secondary plastic surgeon (not a colleague, not a direct referral). However, the distinction lies in the nature of the follow-up, as prearranged and coordinated care allows for direct communication between the operative and managing surgeons, and the alternative has the potential for numerous delays in care and ultimately disastrous outcomes. The ASPS Code asserts that if the primary plastic surgeon does not arrange appropriate postoperative care for their primary patient they are engaging in an unethical practice, which would be a detriment to the patient and might merit expulsion of the surgeon from the ASPS. As plastic surgery patients have increased access to the internet, one might argue that patient’s autonomy in arranging which plastic surgeon to see after experiencing a complication is out of the control of the primary surgeon. A well-outlined plan of postoperative care and fees with a secondary plastic surgeon should be arranged prior to surgery. This may ensure patient compliance and establish a protocol for reimbursement and the recognition and treatment of any complications.

When physicians do agree to the transfer of care, reconstructive services are distinguished by the use of the CPT modifiers −54 and −55. Modifier −54 applies to surgical care only, while modifier −55 applies to postoperative management. Of note, modifier −54 indicates that the surgeon is relinquishing all or part of the postoperative care to another physician, and the physician who furnishes postoperative management other than the primary surgeon bills with modifier −55. The receiving physician is mandated to provide at least one service before billing for any part of the postoperative care, and the date of surgery and date of transfer of care must be clearly documented [12].

Specialty Tourism

While a plastic surgeon may feel an underlying sense of professional responsibility when treating another plastic surgeon’s complication, undoubtedly there is increased hesitation and tension when the referred patient has undergone a procedure by someone who is not a plastic surgeon. Jones et al. [13] describe territorial “turf wars” among physicians as dangerous because they have “nothing to do with responsible patient care and everything to do with pique, turf, and money.” Rejecting a patient with an urgent need for care simply because the patient sought affordable medical care elsewhere has been argued as ethically questionable and may place a false sense of causality for the patient’s complication on the other physician/surgeon.

In reality, surgeon skill and technique are often only partly responsible for operative complications [14]. Melendez and Alizadeh [3] found that the rate of complications from cosmetic plastic surgery procedures by non-plastic surgeons (otolaryngologists, oral surgeons, ophthalmologists, general surgeons, obstetrician-gynecologists) was as high (30 %) as that for general plastic surgeons. As a result, the argument that a plastic surgeon should not treat a patient who was previously treated by a non-plastic surgeon because of the latter’s inherent lack of skill is not grounded in evidence, and more importantly, is ethically questionable.

Similarly, a plastic surgeon board certified in several fields may face an ethical dilemma when caring for patients who have been treated by a surgeon in another similar or shared field, such as facial plastic surgery and otolaryngology. For example, specialty tourism where buttock lipoinfiltration is performed by a facial plastic surgeon demonstrates the need for ethical and reasonable standards of what are appropriate privileges for a “facial” plastic surgeon and when governing boards should be involved when complications arise (Fig. 3).

A 32-year-old patient presented with fat necrosis and multiple fistulas with draining purulence following the placement of 1,000 ml of lipoinfiltration in each buttock by a surgeon that specializes in facial plastic surgery. The arrow marks a focal area of pain and fat necrosis that subsequently liquefied and was aspirated with resultant purulence and contour deformity (patient consent was obtained for the use of her images)

Conclusions

As medical tourism continues to evolve into a global healthcare phenomenon, plastic surgeons will continue to consult on increasing numbers of patients who have previously undergone medical care through macro-tourism, micro-tourism, and interdisciplinary tourism. Broad principles have been set forth by organizations such as ASPS, ABPS, AMA, and ISAPS, but the lack of patient- and physician-specific guidelines may create delays in appropriate care, and ultimately surgeon-specific complication rates may be skewed and best-practice techniques adversely affected. We have provided guidelines to optimize patient care and safety through the use of ethical duty, appropriate preoperative planning, and transparent financial obligations. These guidelines ensure patient safety by not only allowing quick access to a specialist who can identify and manage complications, but also through the maintenance of and adherence to postoperative regimens and protocols. By ensuring best practices through the proposed guidelines, plastic and reconstructive surgery would be the first specialty to specifically address the postoperative safety and care of patients from tourism medicine. Such guidelines not only ensure patient satisfaction and safety, they also ultimately guide and protect the plastic surgeon managing patient care.

References

Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Medical tourism: consumers in search of value. http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-Croatia/Local%20Assets/Documents/hr_Medical_tourism.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

Pollard K (2013) Medical tourism: Trends for 2012 and beyond. Int Med Travel J. http://www.imtj.com/articles/2011/medical-tourism-trends/. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

Melendez MM, Alizadeh K (2011) Complications from international surgery tourism. Aesthet Surg J 31(6):694–697

York D (2008) Medical tourism: the trend toward outsourcing medical procedures to foreign countries. J Contin Educ Health Prof 28(2):99–102

International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. ISAPS key guidelines for plastic surgery travelers. http://www.isaps.org/medical-procedures-abroad-the-key-guidelines-for-plastic-surgery-travelers.html. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

American Board of Plastic Surgery. Code of ethics of the American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS), last revised November 2011. https://www.abplsurg.org/documents/ABPS_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Code of ethics of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), last updated March 2012. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/ByLaws/Code_of_Ethics_March12.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. CDC urges plastic surgeons to be alert for rapidly growing Mycobacterium infections from cases performed in the Dominican Republic. Plastic Surgery News: Special Bulletin. http://www.implantinfo.com/media/news/ASPS-plastic-surgery-news-report-547.aspx. Accessed 27 Jan 2014

American Medical Association. AMA guidelines on medical tourism. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/31/medicaltourism.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

Birch J, Caulfield R, Ramakrishnan V (2007) The complications of ‘cosmetic tourism’: An avoidable burden on the NHS. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 60(9):1075–1077

International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2011 (ISAPS). http://www.isaps.org/files/htmlcontents/Downloads/ISAPS%20Results%20-%20Procedures%20in%202011.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2013

Medicare Claims Processing Manual. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2013

Jones JW, McCullough LB, Richman BW (2005) Turf wars: the ethics of professional territorialism. J Vasc Surg 42(3):587–589

Jones JW, McCullough LB (2007) What to do when a patient’s international medical care goes south. J Vasc Surg 46(5):1077–1079

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial interests in any of the products, insurance carriers, or techniques mentioned and have received no external support related to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iorio, M.L., Verma, K., Ashktorab, S. et al. Medical Tourism in Plastic Surgery: Ethical Guidelines and Practice Standards for Perioperative Care. Aesth Plast Surg 38, 602–607 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0322-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0322-6