Abstract

This work demonstrates the ability of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica cultivated on biodiesel waste to synthesize α-ketoglutaric acid with a minimal content of pyruvic acid as the main byproduct. The key factor promoting the microbial production of α-ketoglutaric acid from the waste is a strong deficiency of thiamine in the cultivation medium. The production of α-ketoglutaric acid by the yeast can be regulated by changing the concentration of nitrogen, iron, zinc, copper, and manganese in the medium, as well as by pH medium and the aeration rate. The optimization of these parameters in flask experiments allowed us to increase the concentration of α-ketoglutaric acid in the medium by 2.6 times and to shift the α-ketoglutaric acid/pyruvic acid ratio from 5:1 to 30:1. During cultivation in a fermentor under optimized conditions, Y. lipolytica produced 80.4 g/L α-ketoglutaric acid with a process selectivity of 96.7% and the product yield (YKGA) equal to 1.01 g/g.

Key points

• α-Ketoglutaric acid is commercially important biotechnological product.

• Biosynthesis of α-ketoglutaric acid from biodiesel waste.

• Optimization of cultivation medium and nutrition medium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Now the annual world production of biodiesel is 41 million tons and increases by 4.5% each year. The production of one ton of biodiesel gives rise to 100–150 kg of waste byproduct, representing a mixture of glycerol (40–60%); free fatty acids, mono-, di-, and triglycerides; methanol; methyl ester; water; and traces of catalysts. The most promising method of waste removal is its conversion by microorganisms to valuable organic compounds, such as proteins, lipids, polyols, polyhydroxybutyrate, and citric and succinic acids (Thompson and He 2006; Debabov 2008; Chatzifragkou et al. 2011; Rywińska et al. 2013; Magdouli et al. 2017; Papanikolaou et al. 2017; Vivek et al. 2017; Do et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2019).

Recently, there is increasing interest to the production of α-ketoglutaric acid (KGA) from the glycerol-containing biodiesel waste with the aid of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica (Zhou et al. 2010, 2012; Otto et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2014, 2015, 2016; Zeng et al. 2017; Cybulski et al. 2018; Fickers et al. 2020).

The microbial production of KGA has an advantage over chemical synthesis, primarily due to the low toxicity of the microbially produced product. Such KGA can safely be used in medicine for antitumor therapy, treatment of schizophrenia, alcoholism, and other disorders, as well for diagnostics of a wide range of diseases (hepatitises, myocardium infections, muscle dystrophy, dermatitises, and others) (Finogenova et al. 2005; Stottmeister et al. 2005; Aurich et al. 2012; Otto et al. 2011, 2013; Guo et al. 2016; Song et al. 2016; Fickers et al. 2020). Besides, the chemically produced KGA has a high cost of $15–20 per kg which presumably can be reduced tenfold, as is evident from the low cost of other organic acids produced microbially on an industrial scale. Indeed, the cost of thus produced citric, lactic, and itaconic acids is as low as 0.6, 1.5, and $2.0/kg, respectively (Zeng et al. 2017).

The conversion of biodiesel waste into KGA by the yeast Y. lipolytica has a great disadvantage related to the simultaneous formation of pyruvic acid (PA) (Zhou et al. 2010, 2012; Otto et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2014, 2015, 2016; Zeng et al. 2017; Cybulski et al. 2018; Fickers et al. 2020). This significantly reduces the product yield (YKGA) and complicates the process of KGA isolation.

The aim of this work was to study the main peculiarities of KGA synthesis from biodiesel waste by yeast Y. lipolytica and to determine conditions favoring the production of KGA with a minimal content of PA.

Materials and methods

Yeast strain

Experiments were carried out with the yeast strain Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412, which was selected earlier and showed its ability to synthesize KGA from ethanol and rapeseed oil in sufficient amounts (Kamzolova et al. 2012, Kamzolova and Morgunov 2013).

Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade (Mosreactiv, Russia). Biodiesel waste contained 70.8% glycerol and 23.9% fatty acids. Composition of fatty acids (% of the sum): tetradecanoic, 0.2; palmitic, 12.7; stearic, 18.0; oleic, 11.3; linoleic, 49.2; α-linolenic, 8.3; eicosanoic, 0.3.

Main medium

Initially, we used Reader medium containing (g/L): (NH4)2SO4, 3.0; МgSO4·7H2O, 0.7; Ca(NO3)2·4H2O, 0.4; NaCl, 0.5; KH2PO4, 1.0; K2HPO4, 0.2. This medium was supplemented with the microelement solution containing (mg/L): KJ, 0.1; Na2B4O7·7H2O, 0.08; MnSO4·5H2O 0.05; ZnSO4·7H2O 0.04; CuSO4, 0.04; Na2MoO4, 0.03; FeSO4(NH4)2SO4·6H2O, 0.35 (Burkholder et al. 1944) and the essential vitamin thiamine. The concentrations of thiamine and biodiesel waste were varied as described in the text.

Cultivation conditions

The effects of thiamine, biotin, and nitrogen source were studied using 750-mL Erlenmeyer flasks with 50 mL of Reader medium supplemented with 40 g/L biodiesel waste. The flasks were shaken at 180 rpm. The cultivation temperature was 29 °C. The pH of the medium was maintained during cultivation at a value between 3.5 and 6.0 by the daily addition of a sterile 10% solution of KOH. Thiamine and nitrogen source were added as indicated in the text. The cultivation time was 8 days.

The effect of pH on acid formation by growing cells was studied using the cultivation medium with the increased concentrations of the following salts (mg/L): ZnSO4·6H2O, 25.1; MnSO4·5H2O, 1.3; CuSO4·5H2O, 5.5; and FeSO4·7H2O, 14.9, while thiamine was in shortage (0.15 μg/L). To facilitate the maintenance of pH on the desired level (between 2.0 and 8.0), 1 M phosphate buffer was added to each cultivation flask in a volume of 10 mL. During cultivation, the pH of the medium was determined every 12 h and, if necessary, corrected by adding a certain volume of 10% solution of either KOH or H2SO4.

In experiments on the effect of pH on acid formation by resting cells, the inoculum was grown for 3 days in a 10-l ANKUM-2 M fermentor (IBP RAN, Russia) with 5 L of a modified Reader medium supplemented with 20 g/L biodiesel waste and a small amount of thiamine (0.15 μg/L). The cultivation temperature, pH, and the concentration of dissolved oxygen (pO2) were automatically maintained at levels of 29 °С, 5.0 units, and 20% oxygen saturation, respectively. After 3 days of cultivation, the yeast cells were separated from the medium, washed, and placed in amounts of 3 g cells/L in the flasks with the modified Reader medium without thiamine and nitrogen source. The pH values of media in different flasks were between 2.0 and 8.0. The flasks were shaken under the same conditions as during the cultivation of growing cells (180 rpm and 29 °C) for 36 h. During the experiment, the pH of the buffered medium decreased insignificantly (by 0.3–0.5 units) and did not require correction.

The effect of aeration rate on acid formation was studied using the same fermentor and the same fermentation conditions except that the concentration of biodiesel waste was increased to 40 g/L and that of thiamine to 0.75 μg/L in order to reach the cell biomass of 10–15 g/L. During the experiment, oxygen was supplied in two regimes. In the first regime (high aeration), the aeration rate was maintained for the first 2 days at 20% oxygen saturation, and with 48 h the aeration rate was elevated to 60% oxygen saturation and maintained at this level to the end of the experiment. In the second regime (low aeration), the aeration rate was maintained at a level of 20% oxygen saturation during the entire experiment. It should be noted that the desired level of aeration (20 and 60% oxygen saturation) was reached by changing the rate of air supply from 0.25 to 10 L air/total amount of medium in liters per min and the agitation rate from 600 to 1000 rpm. As for pH, it was maintained at pH 5 for first 3 days of cultivation, and then allowed to spontaneously drop to 3.0–4.0, and maintained at this level until the end of cultivation in both types of experiments. In both regimes of aeration, after 3 days of cultivation, the medium was additionally supplemented daily with ammonium sulfate in 1.2 g/L portions. If the concentration of dissolved oxygen (pO2) exceeded the preset saturation value by 10%, the biodiesel waste was added to the cultivation medium in 40 g/L portions.

Analyses

Biomass, KGA, PA, and other organic acids in the cultural medium were analyzed as described earlier (Kamzolova et al. 2012; Kamzolova and Morgunov 2013).

The content of lipids and the fatty acid composition was determined as described earlier (Dedyukhina et al. 2014). The content of microelements in cell biomass was determined using a 5100 PCAAS-ZeeMan (Perkin-Elmer) atomic absorption spectrometer (Khavezov and Tsalev 1983).

Calculations

All the data presented are the mean values of three experiments and two measurements for each experiment; standard deviations were calculated (SD < 10%).

The specific rate of KGA synthesis (qKGA) was calculated as the amount of KGA in mg synthesized by 1 g of yeast cells per hour. The product yield (YKGA) was calculated as the amount of KGA in gram found in the culture liquid by the end of the experiment and divided by the amount (in g) of glycerol and fatty acids consumed from the utilized biodiesel waste.

Results

Effect of thiamine

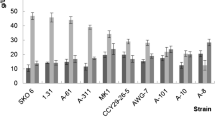

The effect of thiamine on the growth of the yeast strain Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 and the production of ketoacids was studied using this vitamin at concentrations between 0 and 10 μg/L. As seen from Table 1, the yeast can grow even in the absence of added thiamine. The active production of KGA (12.6–13.6 g/L) was observed when thiamine was in a strong shortage (0.15–0.3 μg/L). When the concentration of thiamine in the medium was increased from 0.3 to 5 μg/L, the production of KGA fell by 13 times. The concentration of thiamine equal to 10 μg/L totally suppressed KGA synthesis but provides for the maximum growth of biomass (9.3 g/L). It should be noted that at all thiamine concentrations tested, the culture liquid contained not only the target product KGA but also some amount of PA (from 0.3 to 2.6 g/L) as the main byproduct. The total content of other detected organic acids (citric, isocitric, succinic, fumaric, and malic) was as low as 0.5 g/L. The maximum value of the KGA:PA ratio (5:1) was also observed under the strong deficiency of thiamine (0.15–0.3 μg/L). Similarly, the maximum values of the specific rate of KGA synthesis (qKGA = 35 mg/g h) and the product yield YKGA (0.48 g/g) were attained at the concentration of thiamine equal to 0.15 μg/L. The increase in the thiamine concentration to 0.6 μg/L diminished qKGA and YKGA by 2.5 and 1.7 times, respectively. For this reason, further experiments were carried out at the thiamine concentration equal to 0.15 μg/L.

Effect of nitrogen source

It might be assumed that nitrogen deficiency stops the amination of KGA into glutamate, resulting in the excretion of KGA from the cell into the medium. In fact, however, the decrease in the concentration of nitrogen source not only did not enhance KGA excretion from the cells but even suppressed it (Table 2). When the concentration of the nitrogen source decreased from 0.636 g/L typical of Reader medium to a small value of 0.021 g/L, the yeast biomass declined only by 17%, while KGA biosynthesis by 44 times. As seen from the data of Table 2, the high rate of KGA synthesis (12.6–13.6 g/L) was provided by high concentrations of nitrogen source in the cultivation medium (no less than 0.424 g/L) and the C/N ratio no less than 43:1. The maximum values of the specific rate of KGA synthesis (qKGA = 26–35 mg/g h) and the product yield YKGA (0.43–0.48 g/g) were attained at the concentrations of (NH4)2SO4 between 2 and 10 g/L.

Further experiments were carried out using cultivation media with 3 g/L ammonium sulfate.

Effect of cofactors of key enzymes

The optimal content of Mg, Сa, Na, Zn, Mn, Cu, and Fe was calculated on the basis of the elemental composition of the yeast biomass using the formula (Dudina and Eroshin 1979):

where S is the amount of an element in 1 L of the medium; a is the amount of this element in 1 g of yeast biomass; and X is the planned amount of biomass in 1 L of the medium.

Comparative data on the content of Mg, Сa, Na, Zn, Mn, Cu, and Fe in the optimized and ordinary Reader media are summarized in Table 3. Optimization was based on the elemental composition of the biomass grown in the regime of pH-auxostat at pH = 5 and the cultivation temperature of 29 °C. The planned amount of biomass in calculations was 10 g/L. As seen from Table 3, the ordinary Reader medium contains Na in sufficient amount, Mg and Ca are in excess (2.8- and 7.5-fold, respectively), while Zn, Fe, Cu, and Mn are in shortage (610-, 60-, 140- and 30-fold, respectively).

Further experiments were carried out with the optimized Reader medium which contained Zn, Fe, Cu, and Mn elements in increased amounts (6.1, 3, 1.4, and 0.3 mg/L, respectively).

The effect of biotin on the growth of Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 and production of ketoacids in the optimized medium are shown in Table 4. As seen from Table 4, biotin does not influence yeast growth and KGA production. At the same time, the comparison of data in Tables 2 and 4 clearly shows that the optimization of the Reader medium has doubled the production of KGA.

Effect of pH

The effect of pH on the formation of ketoacids by Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 was studied using two types of yeast cells, growing and resting. The incubation of resting cells in the medium lacking nitrogen source and thiamine did not allow cell reproduction, so the initial concentration of the cells (3 g/L) did not change within the experiment. The results of experiments with these two types of cells are shown in Table 5. As seen from this table, the yeast strain can grow in a wide range of pH values from 2 to 8; however, the intensity of acid formation strongly depends on pH. At the pH values 2 and 8, the concentration of KGA in the culture liquid did not exceed 6.1–6.3 g/L, the growth substrate was consumed only partially, and the KGA yield YKGA was low (0.15–0.16 g/g). In contrast, at pH values from 3 to 7, the concentration of KGA in the culture liquid increased to 22.3–35.3 g/L, while the concentration of PA remained low (0.7–1.2 g/L). The maximum values of KGA production (35.3 g/L) and product yield YKGA (0.88 g/g) were observed at pH = 4. As also seen from Table 5, at the pH values most favorable for growth (from 5 to 7), the specific rate of KGA synthesis (qKGA) is 1.7 times lower than at the pH values relatively unfavorable for growth (3.0–4.5).

As for the resting yeast cells, they can produce KGA at all the pH values studied (Table 5). The specific rate of KGA formation qKGA by these cells remained high (56 mg/g h) even at pH = 2. At the other extreme pH value (pH = 8), qKGA was lower only by two times.

Taking into account all these results, further experiments were carried out controlling pH value at 5.0 during the growth phase and at 3.0–4.0 during the phase of KGA synthesis.

Effect of aeration

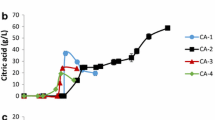

The effect of aeration on the growth of Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 and KGA synthesis was studied in two cultivation regimes differing in the rate of aeration (they are described in detail in the “Materials and methods” section). As seen from Fig. 1, yeast growth was similar within the first 2 days of cultivation in both regimes. Then, in the fermentor with high aeration, yeast growth ceased. However, in the fermentor with low aeration, the yeast continued to grow for 8 days. By this time, the biomass accumulated in this fermentor exceeded that in the fermentor with high aeration by 48%. In both cultivation regimes Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412, the cells simultaneously consume glycerol and fatty acids at different rates, regardless of the growth phase and acid-forming activity of the producer. The effect of aeration on KGA synthesis was opposite; namely, the concentration of KGA in the fermentor with high aeration was 80.4 g/L in comparison with 56.8 g/L in the fermentor with low aeration. At high aeration, the KGA yield (YKGA) and the process productivity reached 1.01 g/g and 0.42 g/L h, respectively, both parameters being lower by 29% in the fermentor with low aeration. In both cultivation regimes, the yeast strain also produced PA in small amounts, so that the selectivity of biodiesel waste conversion into KGA was as high as 96.8%.

Discussion

The biotechnology of KGA production from biodiesel waste with the aid of the yeast Y. lipolytica is based on its inability to synthesize the pyrimidine moiety of the thiamine molecule which is necessary for the normal synthesis of pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase responsible for the oversynthesis of ketoacids (Finogenova et al. 2005; Stottmeister et al. 2005; Aurich et al. 2012; Otto et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2016; Fickers et al. 2020).

As can be seen from Table 1, a deep thiamine deficiency (0.15 μg/L) is a necessary condition of KGA oversynthesis from biodiesel waste by Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412, is in agreement with the results of a study of other strains cultivated on various carbon sources. For example, the wild-type strain Y. lipolytica WSH-Z06 grown on glycerol produced KGA when the concentration of thiamine in the medium was between 0 and 0.2 μg/L and almost did not produce it in the presence of 1 μg/L thiamine (Zhou et al. 2010). Similarly, the oversynthesis of KGA from rapeseed oil by Y. lipolytica was observed within the narrow range of thiamine concentrations between 0.05 and 0.2 μg/L (Kamzolova and Morgunov 2013). In contrast, the same strain grown on ethanol required significantly higher thiamine concentrations for KGA oversynthesis (from 0.2 to 2 μg/L) (Kamzolova et al. 2012). Still higher requirements in thiamine (up to 20 μg/L) were observed for Y. lipolytica H355 and its genetically modified transformants with the superexpressed genes of fumarase and pyruvate carboxylase upon their cultivation in a bioreactor with the glycerol-containing biodiesel waste as the substrate (Otto et al. 2012).

Another necessary condition of KGA oversynthesis by Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 is a relatively high concentration of ammonium sulfate in the cultivation medium (no less than 2 g/L) with the C:N ratio no less than 43:1. Similar data were obtained earlier for the natural strain Y. lipolytica WSH-Z06 and its genetically modified transformants with the superexpressed genes of acetyl-CoA synthetase and pyruvate carboxylase. Namely, these strains grown on glycerol required the С:N ratio from 49:1 to 60:1 for the oversynthesis of ketoacids (Zhou et al. 2010, 2012; Yu et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2012).

The experiments described in this paper show that the optimal proportions between some chemical elements in the cultivation medium favorably influence the preferential synthesis of KGA by Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412. We are referring to those elements that serve as activators or inhibitors of enzymes involved in the assimilation of biodiesel waste and enzymes involved in the metabolism of ketoacids (pyruvate carboxylase, citrate synthase, aconitate hydratase, NAD-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase, etc.). The requirements of Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 in elements such as Mg, Сa, Na, Zn, Mn, Cu, and Fe were studied in the cultivation regime of pH-auxostat when the nutrient medium is fed to the fermentor by the signal of deviation from the preset value of the culture liquid pH. In the steady state of pH-auxostat, all components of the nutrient medium are in excess and provide for all requirements of the culture in chemical elements. As a result, the planned amount of cell biomass can be obtained using the minimal values of nonlimiting concentrations of chemical elements. It was found that the optimum concentrations of Zn, Fe, Cu, and Mn ions determined in the cultivation regime of pH-auxostat enhanced KGA oversynthesis on average by 2.3 times in comparison with cultivation in Reader medium (Table 3). This result is in agreement with the positive effect of some elements on the rate of KGA synthesis. Also, it was reported the positive effect of Ca2+ ions (activator of pyruvate carboxylase) on the rate of KGA synthesis and the KGA:PA ratio (Zhou et al. 2010, 2012; Cybulski et al. 2018). The increased concentrations of Cu2+ and Мn2+ ions in the medium stimulated the accumulation of citric acid and KGA by Y. lipolytica cultivated on glycerol for the purpose of erythritol production (Tomaszewska et al. 2014). The activity of citrate synthase strongly depends on the ionic strength of the solution: 0.01 М NaCl slightly activates the enzyme; 0.02 and 0.04 М NaCl do not influence it, and higher concentrations of NaCl inhibit it (Morgunov 2009). Presumably, the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged hydrated sodium ions and the negatively charged region close to the active center of citrate synthase may disturb the normal operation of this enzyme.

There is an opinion that the two-stage control of pH value (pH = 5 in the growth stage and pH = 3.5 in the phase of acid production) shifts the production of ketoacids by Y. lipolytica toward the formation of KGA (Zhou et al. 2010, 2012; Kamzolova et al. 2012; Kamzolova and Morgunov 2013; Otto et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2012; Guo et al. 2014; Zeng et al. 2017; Cybulski et al. 2018). However, experiments with the resting cells of Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 (Table 5) clearly demonstrate that the strong deficiency of thiamine rather than the pH of the cultivation medium is responsible for KGA excretion from the cells. Indeed, resting yeast cells produce KGA from biodiesel waste even at pH = 2 (Table 5). This is a very important observation because fermentation at low pH values reduces the amount of acid necessary for acidification of the fermentation broth upon the isolation and purification of KGA.

The low rate of culture aeration extends the period of its growth, thus stimulating the accumulation of higher biomass. At the same time, the production of KGA at low aeration is less than at high aeration (Fig. 1). It can be assumed that an increase in biomass and a decrease in acid formation are not the result of a direct effect of low oxygen on the cell and its enzyme systems but rather is associated with the accumulation of excess CO2 in the medium and an increase in the activity of carboxylating enzymes, primarily pyruvate carboxylase. As a result, part of the formed PA is converted into oxaloacetate, which is involved in the synthesis of various cellular components.

The optimized process of KGA production, presented in Fig. 1a, included the next conditions: during the first 2-day stage of cell growth, the aeration rate and pH value are maintained at 20% oxygen saturation and 5.0 units, respectively. Then, the aeration rate is elevated to 60% oxygen saturation. After 3 days of cultivation, pH is allowed to fall spontaneously to 3.0–4.0 and then is maintained at this level to the end of fermentation. Besides, after 3 days of cultivation, the medium is additionally supplemented daily with ammonium sulfate in 1.2 g/L portions. If the concentration of dissolved oxygen рО2 exceeds a value of 10% saturation, biodiesel waste is added to the medium in 40 g/L portions. This process ensured the production of 80.4 g/L KGA with a process selectivity of 96.8%.

According to the literature data, various natural Y. lipolytica strains grown on glycerol-containing waste can produce as much as 39.2–72 g/L KGA (Zhou et al. 2010, 2012; Otto et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2012; Zeng et al. 2017; Cybulski et al. 2018). At the same time, the product yield (YKGA) was found to be relatively low (0.39–0.71 g/g) because of the significant formation of PA. The predominant synthesis of KGA was achieved using the genetically modified Y. lipolytica strain with the superexpressed genes of fumarase and pyruvate carboxylase, which accumulated 138 g/L KGA with a yield of 0.94 g/g during 94-h fermentation (Otto et al. 2012). Another genetically modified Y. lipolytica strain with the superexpressed genes of NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDP1) and pyruvate carboxylase (PYC1) produced 186 g/L KGA with a selectivity of 95% (Yovkova et al. 2014). The superexpression of the carboxylate transporter YALI0B19470g allowed researchers to reach the accumulation of 46.7 g/L KGA and 12.3 g/L PA (Guo et al. 2015).

The putative scheme of assimilation of biodiesel waste by Y. lipolytica and oversynthesis of ketoacids is depicted in Fig. 2. The strain Y. lipolytica VKM Y-2412 realizes concurrent uptake of glycerol and fatty acid fractions during the conversion of biodiesel waste, although glycerol was utilized at a higher rate than fatty acids. These data are comparable with those obtained for Y. lipolytica cultivated on mixtures of saturated free fatty acids (an industrial derivative of animal fat called stearin) and technical glycerol (the main byproduct of biodiesel production facilities) (Papanikolaou et al. 2003). Of interest is the literature data that the mixture of glycerol and fatty acids acts synergetically on the expression of the β-oxidation gene POX2 (Shabbir Hussain et al. 2017). Fatty acid molecules, free or attached to the cell surface, are transported into the cell interior either by diffusion or by special carriers. Inside the cell, fatty acids are converted into acyl-CoA and then undergo a series of β-oxidation reactions giving rise to acetyl-CoA (Fickers et al. 2005; Strijbis and Distel 2010; Sekova et al. 2015). The yeast Y. lipolytica can also assimilate fatty acids by ω-oxidation with the formation of ω-acids, which are further oxidized into aldoacids and then dicarbonic acids. The latter acids undergo β-oxidation to form the respective number of acetyl-CoA molecules (Gatter et al. 2014).

Putative scheme of oxidation of biodiesel waste and the formation of ketoacids in Y. lipolytica. Enzymes: GK, glycerol kinase; GDH, NAD-dependent glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PC, pyruvate carboxylase; CS, citrate synthase; AH, aconitate hydratase; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; KGDH, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; IL, isocitrate lyase; MS, malate synthase

As seen from the scheme in Fig. 2, glycerol is assimilated through its phosphorylation by glycerol kinase; the generated glycerol-3-phosphate is oxidized by NAD-dependent glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (Ermakova and Morgunov 1987; Morgunov et al. 2004; Makri et al. 2010; Workman et al. 2013; Morgunov and Kamzolova 2015). There is evidence that the assimilation of glycerol can be enhanced by superexpression of the GUT1 gene coding for glycerol kinase and the GUT2 gene coding for NAD-dependent glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The respective transformant assimilated glycerol and produced acids by 14 times more active than the parent strain (Mirończuk et al. 2016). Dihydroxyacetone phosphate is transformed into pyruvate by glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase. The pyruvate molecule is converted into acetyl-CoA by two ways: either through decarboxylation by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex to form acetyl-CoA or through carboxylation by pyruvate carboxylase to form oxaloacetate (Ermakova and Morgunov 1987; Morgunov et al. 2004; Makri et al. 2010; Otto et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2012; Yovkova et al. 2014). Thiamine deficiency makes the complete oxidation of pyruvate impossible because of the impairment of pyruvate dehydrogenase. As a result, pyruvate accumulates in the cell and then is excreted into the environment.

Acetyl-CoA generated during the oxidation of fatty acids is metabolized in the TCA cycle to form KGA (Fig. 2). Under thiamine deficiency, the generated KGA cannot be oxidized further in the TCA cycle because of the limitation of the thiamine-dependent α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. As a result, the accumulated KGA is excreted into the culture liquid. Theoretically, the removal of KGA from the cell should disrupt the TCA cycle and stop the generation of KGA. Actually, this does not happen because the removal of intermediates from the TCA cycle is replenished by isocitrate lyase and malate synthase involved in the glyoxylate cycle. The resultant oxaloacetate enters the TCA cycle, thus ensuring its continual operation (Ermakova et al. 1986; Fickers et al. 2005; Otto et al. 2013; Morgunov and Kamzolova 2015; Sabra et al. 2017). As a result, the production of KGA continues until exhaustion of the biodiesel waste. For additional details on α-KG synthesis in Y. lipolytica, refer to the reviews of Otto et al. (2011, 2013), Guo et al. (2015, 2016), and Fickers et al. (2020).

The fact that glycerol and fatty acids were consumed simultaneously is of special importance for the development of the efficient regime of biodiesel waste feeding in the KGA production process by Y. lipolytica. According to the auxiliary concept of Babel (2009), the mixed utilization of physiologically analogous substrates increases the yield of the process (in our case, up to 1.01 g/g) which is of a very important economic consideration.

To conclude, the result of this study and those of other researchers demonstrate that the cheap and renewable biodiesel waste is a great carbon source for the development of microbial technology of KGA production with a minimum content of the main byproduct PA. The promising microorganism for such technology is the yeast Y. lipolytica, which are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) (Groenewald et al. 2014; Zinjarde 2014).

References

Aurich A, Specht R, Müller RA, Stottmeister U, Yovkova V, Otto C, Holz M, Barth G, Heretsch P, Thomas FA, Sicker D, Giannis A (2012) Microbiologically produced carboxylic acids used as building blocks in organic synthesis. In: Wang X, Chen J, Quinn P (eds) Reprogramming microbial metabolic pathways. Subcellular biochemistry, vol 64. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 391–423

Babel W (2009) The auxiliary substrate concept: from simple considerations to heuristically valuable knowledge. Eng Life Sci 9:285–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.200900027

Burkholder P, McVeigh J, Moyer D (1944) Studies on some growth factors of yeasts. J Bacteriol 48:385–391

Chatzifragkou A, Makri A, Belka A, Bellou S, Mavrou M, Mastoridou M, Mystrioti P, Onjaro G, Aggelis G, Papanikolaou S (2011) Biotechnological conversion of biodiesel derived waste glycerol by yeast and fungal species. Energy 36:1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2010.11.040

Cybulski K, Tomaszewska-Hetman L, Rakicka M, Laba W, Rymowicz W, Rywinska A (2018) The bioconversion of waste products from rapeseed processing into keto acids by Yarrowia lipolytica. Ind Crop Prod 119:102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.04.014

Debabov VG (2008) Biofuel. Biotechnology in Russia 1:1–19. (in Russian)

Dedyukhina EG, Chistyakova TI, Mironov AA, Kamzolova SV, Morgunov IG, Vainshtein MB (2014) Arachidonic acid synthesis from biodiesel-derived waste by Mortierella alpina. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 116:429–437. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201300358

Do DTH, Theron CW, Fickers P (2019) Organic wastes as feedstocks for non-conventional yeast-based bioprocesses. Microorganisms 7:229. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7080229

Dudina LP, Eroshin VK (1979) Identification of the limiting component of the medium during microbial continuous cultivation. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol 15(6):817–821 (in Russian)

Ermakova IT, Morgunov IG (1987) Pathways of glycerol metabolism in Yarrowia (Candida) lipolytica yeasts. Mikrobiologiya 57:533–537

Ermakova IT, Shishkanova NV, Melnikova OF, Finogenova TV (1986) Properties of Candida lipolytica mutants with the modified glyoxylate cycle and their ability to produce citric and isocitric acid. I. Physiological, biochemical and cytological characteristics of mutants grown on glucose or hexadecane. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 23:372–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00257036

Fickers P, Benetti P-H, Waché Y, Marty A, Mauersberger S, Smit MS, Nicaud J-M (2005) Hydrophobic substrate utilisation by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, and its potential applications. FEMS Yeast Res 5(6–7):527–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.09.004

Fickers P, Cheng H, Sze Ki Lin C (2020) Sugar alcohols and organic acids synthesis in Yarrowia lipolytica: where are we? Microorganisms 8(4):574. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8040574

Finogenova TV, Morgunov IG, Kamzolova SV, Chernyavskaya OG (2005) Organic acid production by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica: a review of prospects. Appl Biochem Microbiol 41:418–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10438-005-0076-7

Gatter M, Förster A, Bär K, Winter M, Otto C, Petzsch P, Ježková M, Bahr K, Pfeiffer M, Matthäus F, Barth G (2014) A newly identified fatty alcohol oxidase gene is mainly responsible for the oxidation of long-chain ω-hydroxy fatty acids in Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Yeast Res 14(6):858–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/1567-1364.12176

Groenewald M, Boekhout T, Neuvéglise C, Gaillardin C, van Dijck PV, Wyss M (2014) Yarrowia lipolytica: safety assessment of an oleaginous yeast with a great industrial potential. Crit Rev Microbiol 40(3):187–206. https://doi.org/10.3109/1040841X.2013.770386

Guo H, Madzak C, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J (2014) Effects of pyruvate dehydrogenase subunits overexpression on the α-ketoglutarate production in Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:7003–7012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-014-5745-0

Guo H, Liu P, Madzak C, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J (2015) Identification and application of keto acids transporters in Yarrowia Lipolytica. Sci Rep 5:8138. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08138

Guo H, Su S, Madzak C, Zhou J, Chen H, Chen G (2016) Applying pathway engineering to enhance production of alpha-ketoglutarate in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:9875–9884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-016-7913-x

Kamzolova SV, Morgunov IG (2013) α-Ketoglutaric acid production from rapeseed oil by Yarrowia lipolytica yeast. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:5517–5525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-013-4772-6

Kamzolova SV, Chiglintseva MN, Lunina JN, Morgunov IG (2012) α-Ketoglutaric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica and its regulation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 96:783–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4222-x

Khavezov I, Tsalev D (1983) Atomno-absorbcionnyj analiz [Atomic Absorption Analysis]. In: Khavezov I, Tsalev D (eds) . Khimia, Leningrad, p 144 (in Russian)

Kumar LR, Yellapu SK, Tyagi RD, Zhang X (2019) A review on variation in crude glycerol composition, bio-valorization of crude and purified glycerol as carbon source for lipid production. Bioresour Technol 293:122155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122155

Magdouli S, Guedri T, Tarek R, Brar SK, Blais JF (2017) Valorization of raw glycerol and crustacean waste into value added products by Yarrowia lipolytica. Bioresour Technol 243:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.074

Makri A, Fakas S, Aggelis G (2010) Metabolic activities of biotechnological interest in Yarrowia lipolytica grown on glycerol in repeated batch cultures. Bioresour Technol 101(7):2351–2358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.024

Mirończuk AM, Rzechonek DA, Biegalska A, Rakicka M, Dobrowolski A (2016) A novel strain of Yarrowia lipolytica as a platform for value-added product synthesis from glycerol. Biotechnol Biofuels 9(1):180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-016-0593-z

Morgunov IG (2009) Metabolic organization of oxidative pathways of Yarrowia lipolytica yeast – producers of organic acids. Dissertation, Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Microorganisms. (in Russian)

Morgunov IG, Kamzolova SV (2015) Physiologo-biochemical characteristics of citrate-producing yeast Yarrowia lipolytica grown on glycerol-containing waste of biodiesel industry. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99(15):6443–6450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-6558-5

Morgunov IG, Kamzolova SV, Perevoznikova OA, Shishkanova NV, Finogenova TV (2004) Pyruvic acid production by a thiamine auxotroph of Yarrowia lipolytica. Process Biochem 39:1469–1474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00259-0

Otto C, Yovkova V, Barth G (2011) Overproduction and secretion of α-ketoglutaric acid by microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 92:689–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3597-4

Otto C, Yovkova V, Aurich A, Mauersberger S, Barth G (2012) Variation of the by-product spectrum during α-ketoglutaric acid production from raw glycerol by overexpression of fumarase and pyruvate carboxylase genes in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 95:905–917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4085-1

Otto C, Holz M, Barth G (2013) Production of organic acids by Yarrowia lipolytica. In: Barth G (ed) Yarrowia lipolytica. Microbiology monographs, vol 25. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38583-4_5

Papanikolaou S, Muniglia L, Chevalot I, Aggelis G, Marc I, Papanikolaou S, Muniglia L, Chevalot I, Aggelis G, Marc I (2003) Accumulation of a cocoa-butter-like lipid by Yarrowia lipolytica cultivated on agro-industrial residues. Curr Microbiol 46:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-002-3833-3

Papanikolaou S, Rontou M, Belka A, Athenaki M, Gardeli C, Mallouchos A, Kalantzi O, Koutinas AA, Kookos IK, Zeng A-P, Aggelis G (2017) Conversion of biodiesel-derived glycerol into biotechnological products of industrial significance by yeast and fungal strains. Eng Life Sci 17:262–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.201500191

Rywińska A, Juszczyk P, Wojtatowicz M, Robak M, Lazar Z, Tomaszewska L, Rymowicz W (2013) Glycerol as a promising substrate for Yarrowia lipolytica biotechnological applications. Biomass Bioenergy 48:148–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.11.021

Sabra W, Bommareddy RR, Maheshwari G, Papanikolaou S, Zeng AP (2017) Substrates and oxygen dependent citric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica: insights through transcriptome and fluxome analyses. Microb Cell Factories 16(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-017-0690-0

Sekova VY, Isakova EP, Deryabina YI (2015) Biotechnological applications of the extremophilic yeast Yarrowia lipolytica (review). Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol 51(3):290–304 (in Russian). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0003683815030151

Shabbir Hussain M, Wheeldon I, Blenner MA (2017) A strong hybrid fatty acid inducible transcriptional sensor built from Yarrowia lipolytica upstream activating and regulatory sequences. Biotechnol J 12(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.201700248

Song Y, Li J, Shin HD, Liu L, Du G, Chen J (2016) Biotechnological production of alpha-keto acids: current status and perspectives. Bioresour Technol 219:716–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.08.015

Stottmeister U, Aurich A, Wilde H, Andersch J, Schmidt S, Sicker D (2005) White biotechnology for Green chemistry: fermentative 2-oxocarboxylic acids as novel building blocks for subsequent chemical syntheses. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 32:651–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295-005-0254-x

Strijbis K, Distel B (2010) Intracellular acetyl unit transport in fungal carbon metabolism. Eukaryot Cell 9(12):1809–1815. https://doi.org/10.1128/EC.00172-10

Thompson JC, He BB (2006) Characterization of crude glycerol from biodiesel production from multiple feedstocks. Appl Eng Agric 22:261–265. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.20272

Tomaszewska L, Rymowicz W, Rywinska A (2014) Mineral supplementation increases erythrose reductase activity in erythritol biosynthesis from glycerol by Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 172:3069–3078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-014-0745-1

Vivek N, Sindhu R, Madhavan A, Anju AJ, Binod P (2017) Recent advances in the production of value added chemicals and lipids utilizing biodiesel industry generated crude glycerol as a substrate – metabolic aspects, challenges and possibilities: an overview. Bioresour Technol 239:507–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.056

Workman M, Holt P, Thykaer J (2013) Comparing cellular performance of Yarrowia lipolytica during growth on glucose and glycerol in submerged cultivations. AMB Express 3(1):58. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-0855-3-58

Yin X, Madzak C, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J (2012) Enhanced alpha-ketoglutaric acid production in Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06 by regulation of the pyruvate carboxylation pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 96:1527–1537. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-0855-3-58

Yovkova V, Otto C, Aurich A, Mauersberger S, Barth G (2014) Engineering the α-ketoglutarate overproduction from raw glycerol by overexpression of the genes encoding NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase and pyruvate carboxylase in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:2003–2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-013-5369-9

Yu Z, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J (2012) Enhanced α-ketoglutaric acid production in Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06 by an improved integrated fed-batch strategy. Bioresour Technol 114:597–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.021

Zeng W, Zhang H, Xu S, Fang F, Zhou J (2017) Biosynthesis of keto acids by fed-batch culture of Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06. Bioresour Technol 243:1037–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.063

Zhou J, Zhou H, Du G, Liu L, Chen J (2010) Screening of a thiamine-auxotrophic yeast for alpha-ketoglutaric acid overproduction. Lett Appl Microbiol 51:264–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02889.x

Zhou J, Yin X, Madzak C, Du G, Chen J (2012) Enhanced α-ketoglutarate production in Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06 by alteration of the acetyl-CoA metabolism. J Biotechnol 161:257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.05.025

Zinjarde SS (2014) Food-related applications of Yarrowia lipolytica. Food Chem 152:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.117

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and I.M. conceived and designed research. S.K. conducted experiments. S.K. and I.M. analyzed data. S.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This review does not include any researches with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kamzolova, S.V., Morgunov, I.G. Optimization of medium composition and fermentation conditions for α-ketoglutaric acid production from biodiesel waste by Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104, 7979–7989 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10805-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10805-7